manhattan project

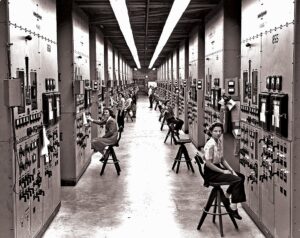

During World War II, a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, joined the Manhattan Project at the Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Known as the Calutron Girls, the group worked for the project from 1943 to 1945. The women were taught to monitor dials and watch meters for calutrons, which are mass spectrometers adapted for separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons for use during World War II. While the women worked at their jobs, and learned how to read the instruments they were required to monitor, they were not allowed to know the purpose of these things.

During World War II, a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, joined the Manhattan Project at the Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Known as the Calutron Girls, the group worked for the project from 1943 to 1945. The women were taught to monitor dials and watch meters for calutrons, which are mass spectrometers adapted for separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons for use during World War II. While the women worked at their jobs, and learned how to read the instruments they were required to monitor, they were not allowed to know the purpose of these things.

They were actually monitoring the manufacturing of enriched uranium that was to be used to make the “Little Boy” atomic bomb for the Hiroshima nuclear bombing to be carried out on August 6, 1945. The Manhattan Project, which was established to develop nuclear weapons, required uranium-235 (U235), the fissionable isotope of uranium. The vast majority of uranium that is mined from the ground is uranium-238. Only about while only 0.7% is U235. The scientists in charge of the project developed several processes for separating the isotopes of uranium, including electromagnetic separation and gaseous diffusion.

“The Y-12 factory was built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to house 1,152 calutrons, a machine used for isotope separation. The word “calutron” is a portmanteau of California University Cyclotron. Calutrons, a variation on mass spectrometers, work by combining uranium with chlorine to make uranium tetrachloride, which is then ionized and put in a vacuum chamber with a magnetic field. When the charged particles move through the magnetic field, they move in a curve, the radius of which is proportional to the mass of the particles. The two isotopes differ in mass by about 1% and can thus be separated.”

The process of separating the U235 Uranium out of the oar was relatively simple, but it still required people to constantly monitor the calutrons. Unfortunately, during World War II, many of the men were fighting. That left a shortage of labor. There simply weren’t enough scientists to operate all of the calutrons. So, the government recruited farm girls to operate the calutrons instead. The main reason for using the young women, was that they were readily available, accustomed to hard work. A stipulation of their employment was that they were not to ask excessive questions, and they had to be loyal and docile. I’m sure these women thought they were doing something top secret and all, but I don’t think they had any idea of the gravity of this project. Lives were on the line, and lives would be lost. Still, they didn’t know that, so I suppose their superiors assumed it would let them sleep at night. I suppose it did. These women honestly didn’t know what they were a part of…some until years later. They would never forget what they did, and they would always wonder if it was right or wrong.

The Tennessee Eastman Company, which ran the Y-12 site, recruited around 10,000 local women between 1943 and 1945. They hired train operators with only a high school education, and they used a large local advertising campaign to recruit workers. One ad read, “When you’re a grandmother you’ll brag about working at Tennessee Eastman.” Word of mouth brought in several other workers. Of course, in hard times, a big motivator was the money being paid. Plus, these women were patriots, and this work was for the war effort. They were trained for three weeks, and they went to work.

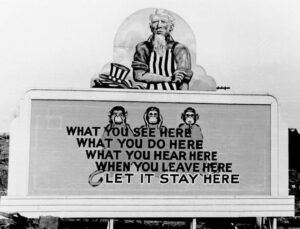

The Tennessee Eastman Company was loyal to the cause. They put a billboard on the premises reading “What you see here / what you do here / what you hear here / when you leave here / let it stay here,” with three wise monkeys to demonstrate “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” Another billboard at the Oak Ridge location,  encouraged secrecy among workers. These companies demanded secrecy and confidentiality…if these women wanted to keep their jobs. According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” Of course, that was correct, but these women would have to live with what they did, once they knew what it was. Testimonies said women who talked about what they were doing disappeared. One young woman who “disappeared” was said to have “died from drinking some poison moonshine.” If they were too nosy about what they were working on, they were replaced. Cars going in and out were searched, and letters were opened and read. This was vital and this was no joke. Anything but secrecy would not be tolerated.

encouraged secrecy among workers. These companies demanded secrecy and confidentiality…if these women wanted to keep their jobs. According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” Of course, that was correct, but these women would have to live with what they did, once they knew what it was. Testimonies said women who talked about what they were doing disappeared. One young woman who “disappeared” was said to have “died from drinking some poison moonshine.” If they were too nosy about what they were working on, they were replaced. Cars going in and out were searched, and letters were opened and read. This was vital and this was no joke. Anything but secrecy would not be tolerated.

The work these women did was not what would be considered labor intensive by any means. The women sat on high stools for 8-hour shifts, seven days per week, “monitoring gauges and adjusting knobs to keep the needles where they were supposed to be and recording readings.” The knobs the women were adjusting were simply labeled with cryptic letters. The women did not know what the letters stood for. What they were taught was that “if you got your M voltage up and your G voltage up, then Product would hit the birdcage in the E box at the top of the unit and if that happened, you’d get the Q and R you wanted.” Okay…whatever that meant. All they knew was that they had to make sure the machine remained at the correct temperature. That was vital and if it got too hot, they used liquid nitrogen to cool it down. If the needles reached a point where they could not control them, they had to call someone else to come help…immediately!!!

Former Calutron Girl Wynona Arrington Butner said, “We all wore little fountain-pen-sized dosimeters. Part of signing out of the plant was to check the amount of radiation that you had absorbed every day.” Civilian workers paid $2.50 per month (single) or $5.00 per month (family) for medical insurance. I don’t know if they understood what radiation could do to them or not, but if they did, they would know that the wages paid and even the insurance help, was probably not enough.

Some Calutron Girls had more of a sense of what they were working on than others. Butner, who had some training in chemistry, said she and others with a similar background had some sense of what they were doing. They knew they were producing “the Product,” and they guessed it was somewhere near the bottom of the periodic table. Willie Baker, on the other hand, said, “Even when somebody let it slip that we were building a bomb, I didn’t know what they meant. I was just a country girl. I had no understanding of what an atomic bomb was.” Later, I’m sure the gravity of the work she did, weighed heavily on Baker.

Over two years, the calutrons at Y-12 had produced about 140 pounds of U235. This was enough to make the first atomic bomb. By December 1945, enough uranium for a second Little Boy was available. Then, it all hit these women, because on August 6, 1945, when the US dropped the first bomb, “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima, Japan, the Calutron Girls were finally told what they had been working on. I can’t imagine how they must have felt. When they heard the news, some women were working, while others were in their dorm rooms. Someone came and told them that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan, and everyone there had played a part in making it. Yes, it was the enemy, and death happens in war. Nevertheless, the Calutron Girls had mixed feelings about their part in the bomb. Ruth Huddleston said she was “really happy at the time, because her boyfriend was stationed in Germany, and this would bring him back.” Still, it bothered her that she had a part in killing so many people, but she accepted that “if the bomb hadn’t been dropped, then probably more people would have been killed. …But even today, if I think too much about it, it bothers me.” Butner had a similar experience, because at the time, she was happy that the war was over and people she knew in the service could come  home, but over time, she began to question whether it was the right thing to do. I think many people over the years have questioned it, but good, bad, or ugly, World War II was over.

home, but over time, she began to question whether it was the right thing to do. I think many people over the years have questioned it, but good, bad, or ugly, World War II was over.

Most of the Calutron Girls are gone now, but those who remain, such as Huddleston, regularly shared their stories with the public, often alongside Oak Ridge historian Ray Smith. The women are the subject of the nonfiction book “The Girls of Atomic City” by Denise Kiernan and the novel “The Atomic City Girls” by Janet Beard. I’m sure that many of these women suffered nightmares over the work they did, but did not know they were doing. While I know they suffered much anxiety over that, I hope they also know that we are so grateful for their service to this great nation.