Major General Ormsby Mitchel

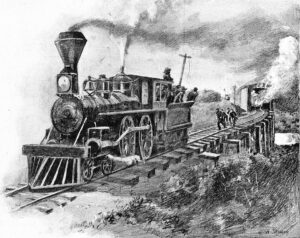

During the Civil War, things like supply lines and lines of communication were crucial to both sides. The railroads became an important asset, as well as a liability, to both sides, depending on what they were carrying and where it was headed. On April 12, 1862, volunteers from the Union Army, led by civilian scout James J Andrews, commandeered a train called The General, and took it northward from Georgia toward Chattanooga, Tennessee. En route, they did as much damage as possible to the vital Western and Atlantic Railroad (W and A) line from Atlanta to Chattanooga. They were pursued for 87 miles by Confederate forces, trying at first to keep up on foot, and later resorting to a succession of locomotives, including The Texas.

During the Civil War, things like supply lines and lines of communication were crucial to both sides. The railroads became an important asset, as well as a liability, to both sides, depending on what they were carrying and where it was headed. On April 12, 1862, volunteers from the Union Army, led by civilian scout James J Andrews, commandeered a train called The General, and took it northward from Georgia toward Chattanooga, Tennessee. En route, they did as much damage as possible to the vital Western and Atlantic Railroad (W and A) line from Atlanta to Chattanooga. They were pursued for 87 miles by Confederate forces, trying at first to keep up on foot, and later resorting to a succession of locomotives, including The Texas.

Known as The Great Locomotive Chase, the military raid was also called the Andrews’ Raid or Mitchel Raid (after Major General Ormsby Mitchel, who had earlier assisted in the capture of Nashville and accepted the surrender of the city). In the end, as often happens in escapades like this, the raid made sensational headlines in newspapers, but it really had little impact on the war. It didn’t stop supply lines for the South or start new ones for the North.

In February, the Union soldiers captured Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, and Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston knew he had to withdraw his forces from central Tennessee to reorganize. Johnston evacuated Nashville on February 23rd, and Nashville became the first Confederate state capital to fall to the Union. For Major General Don Carlos Buell, the taking of Nashville was enough, and on March 11th, Buell’s army was merged into the new Department of the Mississippi under General Henry Halleck. It was then that James J Andrews, a Kentucky-born civilian serving as a secret agent and scout in Tennessee approached Buell with a plan to take eight men to steal a train in Georgia and drive it north. Buell authorized the expedition in August 1863. Andrews, a train engineer in Atlanta, was willing to defect to the Union with his train, and without Andrews, taking over the train would have proved difficult. Getting onboard would have been easy enough, but running the train without experienced personnel is next to impossible. Since Andrews was willing to defect, he might also be able to supply a volunteer train crew to assist in running the train, tearing up track, and burning  bridges, so they would have an even greater chance of succeeding. The main target of the operation was the railway bridge at Bridgeport, Alabama, but Andrews had several other bridges in Georgia and Tennessee in mind too. Some of the men from Major General Mitchel’s division, encamped at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, were tapped to be the volunteers for this first raid.

bridges, so they would have an even greater chance of succeeding. The main target of the operation was the railway bridge at Bridgeport, Alabama, but Andrews had several other bridges in Georgia and Tennessee in mind too. Some of the men from Major General Mitchel’s division, encamped at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, were tapped to be the volunteers for this first raid.

The group of raiders moved south forty miles on foot to the Confederate railhead at Tullahoma. Then the caught a train to Marietta, Georgia. It was then that the operation hit its first snag, when Andrews discovered the engineer had been pressed into service elsewhere. Upon inquiring if any of the raiders knew how to operate a locomotive, they found that none did, and the raid was called off. Two raiders were also confronted by Confederate soldiers while trying to cut the telegraph lines, but successfully pretended to be overworked wiremen. Then the raiders returned north to Union lines, arriving about a week after they had departed. Andrews spent several days rearranging the operation and conducting reconnaissance on the Western and Atlantic Railroad before he headed north to federal lines too. The original raiders all refused to volunteer for the second raid, fearing the enemy. One said that “he felt all the time he was in the enemy’s country as though he had a rope around his neck.”

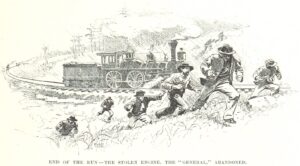

While the first raid was a bust, the second raid went off pretty well. The General was taken while the crew was a breakfast at the Lacey Hotel in Atlanta, and despite all the efforts to catch them, it arrived at milepost 116.3, north of Ringgold, Georgia, just 18 miles from Chattanooga and out of fuel. Andrews’s men abandoned The General and scattered. Andrews and all of his men were caught within two weeks. They even caught two volunteers who had the hijacking. Mitchel’s attack on Chattanooga was a failure.

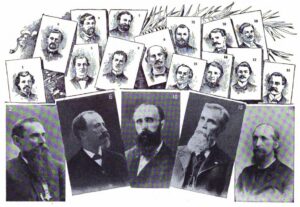

All of the raiders were charged with “acts of unlawful belligerency.” The civilians among them were charged as unlawful combatants and spies. They were tried in military courts or courts-martial. Andrews was tried in

Chattanooga, found guilty, and hanged on June 7 in Atlanta. Seven others were transported to Knoxville and convicted as spies. They were returned to Atlanta and were hanged too. Their bodies were buried unceremoniously in an unmarked grave. Those bodies were later reburied in Chattanooga National Cemetery.

Chattanooga, found guilty, and hanged on June 7 in Atlanta. Seven others were transported to Knoxville and convicted as spies. They were returned to Atlanta and were hanged too. Their bodies were buried unceremoniously in an unmarked grave. Those bodies were later reburied in Chattanooga National Cemetery.