london

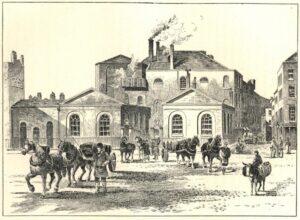

The London Beer Flood occurred as a result of an accident at Meux and Company’s Horse Shoe Brewery in London on October 17, 1814. The disaster unfolded when a 22-foot-tall wooden vat containing fermenting porter ruptured. The force of the escaping beer dislodged the valve of another vat and caused the destruction of several large barrels, releasing a total of between 128,000 and 323,000 imperial gallons (approximately 154,000 to 388,000 US gallons) of beer.

The London Beer Flood occurred as a result of an accident at Meux and Company’s Horse Shoe Brewery in London on October 17, 1814. The disaster unfolded when a 22-foot-tall wooden vat containing fermenting porter ruptured. The force of the escaping beer dislodged the valve of another vat and caused the destruction of several large barrels, releasing a total of between 128,000 and 323,000 imperial gallons (approximately 154,000 to 388,000 US gallons) of beer.

The wave of porter demolished the brewery’s rear wall and flooded the Saint Giles rookery, a slum area. Eight individuals died, including five mourners attending a wake for a two-year-old boy being held by an Irish family. The coroner’s inquest concluded that the eight died “casually, accidentally and by misfortune.” The brewery nearly faced bankruptcy due to the incident but was saved by a tax rebate from HM Excise on the beer lost. Following the disaster, the brewing industry moved away from using large wooden vats. In 1921, the brewery relocated, and the Dominion Theatre now stands in its place. Meux and Company was liquidated in 1961.

In the early 19th century, Meux Brewery was one of London’s two largest breweries, alongside Whitbread. Sir Henry Meux acquired the Horse Shoe Brewery in 1809, located at the intersection of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street. His father, Sir Richard Meux, had earlier been a co-owner of the Griffin Brewery on Liquor-Pond Street, now known as Clerkenwell Road, where he built London’s largest vat, with a capacity of 20,000 imperial barrels. Henry Meux followed in his father’s footsteps by constructing a large vat, a wooden vessel standing 22 feet high and capable of holding 18,000 imperial barrels. To reinforce the vat, eighty long tons of iron hoops were utilized. Meux exclusively brewed porter, a dark beer originating from London and highly favored as the capital’s most popular alcoholic beverage. In the year leading up to July 1812, Meux and Company produced 102,493 imperial barrels. The porter was aged in these large vessels for several months, and up to a year for the highest quality brews.

Behind the brewery lay New Street, a small dead-end road connecting to Dyott Street, situated within the Saint Giles rookery. Spanning eight acres, the rookery was a constantly deteriorating slum teetering on the brink of social and economic collapse, as noted by Richard Kirkland, a professor of Irish literature. Thomas Beames, a preacher at Westminster St James and the author of “The Rookeries of London: Past, Present and Prospective” (1852), referred to the Saint Giles rookery as a gathering place for society’s outcasts. This area also served as the muse for William Hogarth’s 1751 artwork, “Gin Lane.”

Around 4:30pm on October 17, 1814, George Crick, the storehouse clerk at Meux’s Brewery, noticed that one of the iron bands weighing 700 pounds had slipped off a vat. The vessel, standing 22 feet tall, was nearly full, containing 3,555 imperial barrels of ten-month-old porter, filled to within four inches from the top. Since such slippages occurred two or three times annually, Crick was not alarmed. He reported the issue to his supervisor, who assured him it would cause no harm. Crick was instructed to write a note to Mr Young, a brewery partner, to address the repair later.

An hour after a hoop detached, Crick stood thirty feet from the vat, note in hand for Mr Young, when suddenly, the vat burst without warning. The released liquid’s force dislodged a stopcock from an adjacent vat, causing it to release its contents; several hogsheads of porter were lost, contributing to the deluge. An estimated 128,000 to 323,000 imperial gallons were spilled. The brewery’s rear wall, 25 feet high and two and a half bricks thick, was demolished by the force. Bricks from the wall were propelled upwards, landing on the roofs of houses along Great Russell Street.

A 15-foot-high wave of porter crashed into New Street, demolishing two houses and severely damaging two others. In one of the destroyed homes, four-year-old Hannah Bamfield was having tea with her mother and another child when the beer wave swept the mother and the other child into the street, resulting in Hannah’s death. At the second house, a wake for a two-year-old boy was in progress; the boy’s mother, Anne Saville, and four mourners perished. Eleanor Cooper, a 14-year-old servant at the Tavistock Arms on Great Russell Street, was killed by a collapsing brewery wall while she was washing pots. Another victim, Sarah Bates, was found deceased in a different house on New Street. The surrounding land, being flat and poorly drained, allowed the beer to flood into cellars, forcing inhabitants to climb onto furniture to escape drowning. Everyone at the brewery survived, though three workers were rescued from the debris; the superintendent and one worker were taken to Middlesex Hospital with three others.

Rumors began to emerge of hundreds gathering to collect the beer, followed by widespread drunkenness, and a fatality due to alcohol poisoning days later. However, brewing historian Martyn Cornell insists that contemporary newspapers did not mention such chaos or the subsequent death; rather, they depicted the crowds as orderly. Cornell notes that the prevalent press at the time harbored an aversion to the immigrant Irish community in Saint Giles, suggesting that any misconduct would have been reported.

The vicinity behind the brewery revealed a “scene of desolation [that] presents a most awful and terrific appearance, akin to what one might expect from fire or earthquake.” Brewery watchmen charged onlookers to see the remnants of the shattered beer vats, attracting several hundred viewers. Those mourners who perished in the cellar received their own vigil at The Ship public house on Bainbridge Street. Meanwhile, the other victims were displayed by their families in a nearby yard, drawing public attention and financial contributions for their burials. Broader fundraising efforts were also initiated for the affected families.

The coroner’s inquest was held at the Workhouse of the Saint Giles parish on October 19, 1814; George Hodgson, the coroner for Middlesex, oversaw proceedings. The details of the victims were read out as: Eleanor Cooper, age 14; Mary Mulvey, age 30; Thomas Murry, age 3 (Mary Mulvey’s son); Hannah Bamfield, age 4 years 4 months; Sarah Bates, age 3 years 5 months; Ann Saville, age 60; Elizabeth Smith, age 27; and Catherine Butler, age 65.

Hodgson led the jurors to the event’s location, where they observed the brewery and the deceased prior to gathering witness testimony. The initial testimony came from George Crick, who witnessed the entire incident; his brother was among the injured at the brewery. Crick noted that the vat hoops would fail a few times annually, yet this had not previously led to any incidents. Testimonies were also presented by Richard Hawse, the proprietor of the Tavistock Arms, who lost a barmaid in the tragedy, among others. The jury concluded that the eight victims died “casually, accidentally, and by misfortune”. When the coroner’s inquest concluded with a verdict of an act of God, Meux and Company were not required to pay compensation. However, the disaster, including the lost porter, the damaged buildings, and the vat replacement, cost the company £23,000. Following a private petition to Parliament, they received approximately £7,250 from HM Excise, which prevented their bankruptcy. The Horse Shoe Brewery resumed operations shortly thereafter but ceased in 1921 when Meux

transferred their production to the Nine Elms brewery in Wandsworth, acquired in 1914. At closure, the brewery spanned 103,000 square feet. It was demolished the subsequent year, and the Dominion Theatre was constructed on its location. Meux and Company was liquidated in 1961. Following the accident, the brewing industry gradually replaced large wooden tanks with lined concrete vessels.

transferred their production to the Nine Elms brewery in Wandsworth, acquired in 1914. At closure, the brewery spanned 103,000 square feet. It was demolished the subsequent year, and the Dominion Theatre was constructed on its location. Meux and Company was liquidated in 1961. Following the accident, the brewing industry gradually replaced large wooden tanks with lined concrete vessels.

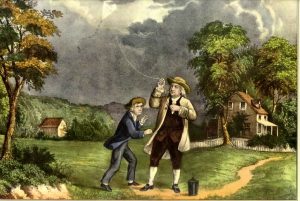

When I first heard about the bizarre phenomenon found under the home of Benjamin Franklin, I thought of a few possibilities. The remains, found in 1998, consisted of 1,200 bones are believed to be from more than 15 human bodies found in the basement of Ben Franklin’s house. Six of the bodies were children. My first thought was, “Please tell me that this is some Indian burial site, or that there is some logical explanation as to why there would be bodies buried in this hero Founding Father’s home.” I have always liked Ben Franklin. I found his “antics” to be so interesting. To say the least, he was a bit strange in his experimentations, and that was enough to make me wonder (and hope it wasn’t so) if Ben Franklin could possibly have some horrid alter ego. He wouldn’t be the first scientist to go off the deep end to experiment on human bodies, but then again, there certainly are people today that have chosen to donate their bodies to science, so why couldn’t that be the case back then. I prayed that was the case.

When I first heard about the bizarre phenomenon found under the home of Benjamin Franklin, I thought of a few possibilities. The remains, found in 1998, consisted of 1,200 bones are believed to be from more than 15 human bodies found in the basement of Ben Franklin’s house. Six of the bodies were children. My first thought was, “Please tell me that this is some Indian burial site, or that there is some logical explanation as to why there would be bodies buried in this hero Founding Father’s home.” I have always liked Ben Franklin. I found his “antics” to be so interesting. To say the least, he was a bit strange in his experimentations, and that was enough to make me wonder (and hope it wasn’t so) if Ben Franklin could possibly have some horrid alter ego. He wouldn’t be the first scientist to go off the deep end to experiment on human bodies, but then again, there certainly are people today that have chosen to donate their bodies to science, so why couldn’t that be the case back then. I prayed that was the case.

At this point, many people would immediately assume that Ben Franklin was some kind of closet killer, who tortured and murdered his victims. It would be thought that the world had been so naive, that we lived in the dark for years, but before you go crafting a murder mystery about him, please be aware that it was revealed that the bodies were used in the study of human anatomy. So, it actually was bodies donated for scientific  research. I certainly didn’t know that they did that sort of thing back then, but it seems that they did.

research. I certainly didn’t know that they did that sort of thing back then, but it seems that they did.

The house, located in London, England was undergoing some conservation work in 1998, when the bones were discovered. Some of the bodies were dismembered, or had trepanned skulls, which is skulls with holes drilled through them. Ben Franklin had lived home in London for nearly twenty years leading up to the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It was more than 200 years later, when the conservation work uncovered the 15 bodies in the basement, buried in a secret, windowless room beneath the garden. While on could imagine horrible things, “The most plausible explanation is not mass murder, but an anatomy school run by Benjamin Franklin’s young friend and protege, William Hewson.” So, it would seem that Ben Franklin either loaned the home to Hewson (a surgeon), stored the bodies for Hewson, or allowed Hewson to do his scientific experiments in the room in the Franklin house. Whatever the case may be, it is apparently well enough documented that the authorities were satisfied that Ben Franklin wasn’t personally involved.

One such speculation was that “Anatomy was still in its infancy, but the day’s social and ethical mores frowned upon it. … A steady supply of human bodies was hard to come by legally, so Hewson, Hunter, and the field’s other pioneers had to turn to grave robbing—either paying professional ‘resurrection men’ to procure cadavers  or digging them up themselves—to get their hands on specimens. Researchers think that 36 Craven was an irresistible spot for Hewson to establish his own anatomy lab. The tenant was a trusted friend, the landlady was his mother-in-law, and he was flanked by convenient sources for corpses. Bodies could be smuggled from graveyards and delivered to the wharf at one end of the street or snatched from the gallows at the other end. When he was done with them, Hewson simply buried whatever was left of the bodies in the basement, rather than sneak them out for disposal elsewhere and risk getting caught and prosecuted for dissection and grave robbing.” Some people speculate that Ben Franklin knew about the goings on, but was not personally involved, still, they thought he might have gone to the lab a few times to check out the proceedings. I hate to think that he knew anything about it, and I would prefer to think that the study of anatomy was done in his absence, but I suppose that our modern-day anatomy studies and autopsies were probably pioneered in a basement somewhere.

or digging them up themselves—to get their hands on specimens. Researchers think that 36 Craven was an irresistible spot for Hewson to establish his own anatomy lab. The tenant was a trusted friend, the landlady was his mother-in-law, and he was flanked by convenient sources for corpses. Bodies could be smuggled from graveyards and delivered to the wharf at one end of the street or snatched from the gallows at the other end. When he was done with them, Hewson simply buried whatever was left of the bodies in the basement, rather than sneak them out for disposal elsewhere and risk getting caught and prosecuted for dissection and grave robbing.” Some people speculate that Ben Franklin knew about the goings on, but was not personally involved, still, they thought he might have gone to the lab a few times to check out the proceedings. I hate to think that he knew anything about it, and I would prefer to think that the study of anatomy was done in his absence, but I suppose that our modern-day anatomy studies and autopsies were probably pioneered in a basement somewhere.

Every time there is a great event like the Olympics, the World’s Fair, or in this case, the Great Exhibition, a stunning new building or structure is built to house the event. The Crystal Palace was originally located in Hyde Park, London, England. It was a cast iron and plate glass structure, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Great Exhibition took place from May 1 to October 15, 1851, with more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet exhibition hall to display their own examples of the latest technology they had developed in the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton. It was 1,851 feet long, with an interior height of 128 feet. It was three times the size of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Some say that the name of the building came from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a “palace of very crystal.”

Every time there is a great event like the Olympics, the World’s Fair, or in this case, the Great Exhibition, a stunning new building or structure is built to house the event. The Crystal Palace was originally located in Hyde Park, London, England. It was a cast iron and plate glass structure, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Great Exhibition took place from May 1 to October 15, 1851, with more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet exhibition hall to display their own examples of the latest technology they had developed in the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton. It was 1,851 feet long, with an interior height of 128 feet. It was three times the size of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Some say that the name of the building came from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a “palace of very crystal.”

The design called for 60,000 panes of glass to adorn the building. On average, a team of 80 men could fix more than 18,000 panes of sheet glass in a week. These were manufactured by the Chance Brothers. The building was finished in 39 weeks. The Crystal Palace boasted the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building. Visitors were shocked and astonished by all the clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights. The interior of the building had full grown trees!! The full-size elm trees that had been growing in the park were simply enclosed within the central exhibition hall near the 27-foot-tall Crystal Fountain. While very nice looking, the trees caused a problem with sparrows becoming a nuisance, and of course, shooting was out of the question inside a glass building. When Queen Victoria mentioned this problem to the Duke of Wellington, he offered the solution, “Sparrowhawks, Ma’am.” Now to me, that is incredulous, because you would simply be replacing on kind of bird with another, and then there was the added problem of bird violence. I don’t think the visitors would be very thrilled about the fighting birds or dropping bodies.

Incredibly, the Palace was relocated after the Great Exhibition, to an open area of South London known as Penge Place which had been excised from Penge Common. The building was rebuilt at the top of Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill, which is an affluent suburb. The Crystal Palace stood in that location from June 1854 until a fire destroyed it in November 1936. After the fire, the suburb was renamed Crystal Palace after the landmark. In addition, a park was placed in the area and named Crystal Palace Park. It surrounds the site, and is home of the Crystal Palace National Sports Centre, which was previously a football stadium that hosted the FA Cup Final between 1895 and 1914. Crystal Palace Football Club were founded at the site and played at the Cup Final venue in their early years. The site still contains Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s Crystal Palace Dinosaurs which date back to 1854.

In the 1920s, a board of trustees was set up under the guidance of manager Sir Henry Buckland. Buckland was a fair man with a great love for the Crystal Palace, decided to restore the building. Following the restoration, the visitors returned, and the Crystal Palace started to become profitable again. Buckland and his staff also worked on improving the fountains and gardens, including the Thursday evening displays of fireworks by Brocks. Then, on the evening of November 30, 1936, Buckland was walking his dog near the Palace with his daughter Crystal. Buckland had named her after the building. Always looking at the building he loved, they noticed a red glow coming from inside. Buckland went in to investigate and found two of his employees fighting a small office fire that had started after an explosion in the women’s cloakroom. Buckland could see that this was a serious fire, so they called the Penge fire brigade. It was too late. Even with the 89 fire engines and over 400 firemen, the fire was too big and too out of control to be able to extinguish it.

The infamous Crystal Palace was destroyed. The fire was so big that its glow could be seen across eight counties. With high winds that night, the fire spread quickly, and in part because of the dry old timber flooring, and the huge quantity of flammable materials in the building it burned to the ground. Buckland said, “In a few hours we have seen the end of the Crystal Palace. Yet, it will live in the memories not only of Englishmen, but the whole world.” The fire brought one-hundred thousand spectators to Sydenham Hill that night. One of the

spectators was Winston Churchill, who said, “This is the end of an age.” Unfortunately, as was common for the era, the Crystal Palace was underinsured, and with a potential rebuild cost of at least £2 million, the building was never rebuilt. John Logie Baird, who had used the South Tower and much of the lower level of the building for mechanical television experiments. Much of his work was destroyed in the fire, and Baird suspected the fire was an act of arson to destroy his work on developing television. Nevertheless, the true cause remains unknown.

spectators was Winston Churchill, who said, “This is the end of an age.” Unfortunately, as was common for the era, the Crystal Palace was underinsured, and with a potential rebuild cost of at least £2 million, the building was never rebuilt. John Logie Baird, who had used the South Tower and much of the lower level of the building for mechanical television experiments. Much of his work was destroyed in the fire, and Baird suspected the fire was an act of arson to destroy his work on developing television. Nevertheless, the true cause remains unknown.

Often when a robbery goes wrong, the would-be robbers decide that the best way out of the situation is to take hostages. The hope is to negotiate a way out of their pending imprisonment. Most hostage takings or sieges last a few hours but on September 28, 1975, The Spaghetti House siege began, and it continued until October 3, 1975. The Spaghetti House was a restaurant in Knightsbridge, London, and when the robbery went wrong, the police were on the scene so quickly that the robbers couldn’t get away. Seeing that they were trapped, the three robbers took the staff down into a storeroom and barricaded themselves in. The three robbers had been involved in black liberation organizations and tried to set the robbery as being politically motivated, thinking that a political standoff might have a better chance of success. The police did not believe them, however, and they stated that this was no more than a criminal act. Finally, they decided that the political ploy was not going to work, so the robbers released all the hostages unharmed after six days. I can’t say for sure that this was the longest robbery siege in history, but if it wasn’t, it ranked right up there. Finally, two of the gunmen gave themselves up, while the ringleader, Franklin Davies, shot himself in the stomach. He survived, and all three were later imprisoned, as were two accomplices. To keep tabs on the situation during the siege, the police used fiber optic camera technology, giving them live surveillance. They monitored the actions and conversations of the gunmen from the audio and visual output. They brought in a forensic psychiatrist to watch the feed and advise the police on the state of the men’s minds, and how to best manage the ongoing negotiations.

Often when a robbery goes wrong, the would-be robbers decide that the best way out of the situation is to take hostages. The hope is to negotiate a way out of their pending imprisonment. Most hostage takings or sieges last a few hours but on September 28, 1975, The Spaghetti House siege began, and it continued until October 3, 1975. The Spaghetti House was a restaurant in Knightsbridge, London, and when the robbery went wrong, the police were on the scene so quickly that the robbers couldn’t get away. Seeing that they were trapped, the three robbers took the staff down into a storeroom and barricaded themselves in. The three robbers had been involved in black liberation organizations and tried to set the robbery as being politically motivated, thinking that a political standoff might have a better chance of success. The police did not believe them, however, and they stated that this was no more than a criminal act. Finally, they decided that the political ploy was not going to work, so the robbers released all the hostages unharmed after six days. I can’t say for sure that this was the longest robbery siege in history, but if it wasn’t, it ranked right up there. Finally, two of the gunmen gave themselves up, while the ringleader, Franklin Davies, shot himself in the stomach. He survived, and all three were later imprisoned, as were two accomplices. To keep tabs on the situation during the siege, the police used fiber optic camera technology, giving them live surveillance. They monitored the actions and conversations of the gunmen from the audio and visual output. They brought in a forensic psychiatrist to watch the feed and advise the police on the state of the men’s minds, and how to best manage the ongoing negotiations.

There were a number of things that potentially led up to the robbery, not that these things were in any way a good excuse. Post-World War II Britain had a shortage of labor. Due to that shortage, the British decided to bring in workers from the British Empire and Commonwealth countries. These people came from poverty areas,  and while they were placed in low-pay, low-skill employment, which forced them to live in poor housing, it probably wasn’t much different than what they came from. Nevertheless, economic circumstances and what were seen by many in the black communities as racist policies applied by the British government, just like in other nations. This led to a rise in militancy, particularly among the West Indian community. The people grew angry, and their feelings were exacerbated by police harassment and discrimination in the education sector. The director of the Institute of Race Relations in the mid-1970s, Ambalavaner Sivanandan said that while the first generation had become partly assimilated into British society, the second generation were increasingly rebellious. These robbers were a part of that second generation.

and while they were placed in low-pay, low-skill employment, which forced them to live in poor housing, it probably wasn’t much different than what they came from. Nevertheless, economic circumstances and what were seen by many in the black communities as racist policies applied by the British government, just like in other nations. This led to a rise in militancy, particularly among the West Indian community. The people grew angry, and their feelings were exacerbated by police harassment and discrimination in the education sector. The director of the Institute of Race Relations in the mid-1970s, Ambalavaner Sivanandan said that while the first generation had become partly assimilated into British society, the second generation were increasingly rebellious. These robbers were a part of that second generation.

The ringleader, Franklin Davies was a 28-year-old Nigerian student who had previously served time in prison for armed robbery. The two men with him were Wesley Dick (later known as Shujaa Moshesh), who was a 24-year-old West Indian; and Anthony “Bonsu” Munroe, a 22-year-old Guyanese. The men were all involved in black liberation organizations at one time or another. Davies had tried to enlist in the guerrilla armies of Zimbabwe African National Union and FRELIMO in Africa. While Munroe had links to the Black Power movement. Dick was an attendee at meetings of the Black Panthers, the Black Liberation Front (BLF), the Fasimba, and the Black Unity and Freedom Party. He regularly visited the offices of the Institute of Race Relations to volunteer and access their library. Sivanandan and the historian Rob Waters identify that the three men were attempting to obtain money to “finance black supplementary schools and support African liberation struggles.”

By the mid-1970s the branch managers started a weekly tradition of closing the London-based Spaghetti House restaurant chain to meet at the company’s Knightsbridge branch. During that time, the outlet would be closed, but managers would deposit the week’s takings there, before it was paid into a night safe at a nearby bank. Of course, that was a well-known fact. So, at approximately 1:30am on Sunday, September 28, 1975, Davies, Moshesh, and Munroe entered the Knightsbridge branch of the Spaghetti House. One carried a sawed-off shotgun, and the others had handguns. The three men burst in and demanded the week’s takings from the chain, which was between £11,000 and £13,000. The restaurant was dimly lit, and it gave the staff a chance to  hide the briefcases of money under the tables. Now infuriated, the three men forced the staff down into the back, but the company’s general manager managed to escape out the rear fire escape.

hide the briefcases of money under the tables. Now infuriated, the three men forced the staff down into the back, but the company’s general manager managed to escape out the rear fire escape.

He quickly called the Metropolitan Police, who were at the scene within minutes. The getaway driver, Samuel Addison, realized that the plan was going wrong, so he decided that it was every man for himself, and drove off in a stolen Ford. The police entered the ground floor, so Davies and his colleagues forced the staff into a rear storeroom measuring 14 by 10 feet, locked the door, barricaded it with beer kegs. They began shouting at the police that they would shoot if they approached the door. The police surrounded the building, and the siege began. It would finally end on October 3, 1975, with the surrender of the robbers, and later the location and arrest of the two accomplices.

.

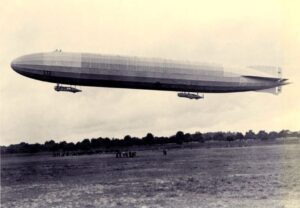

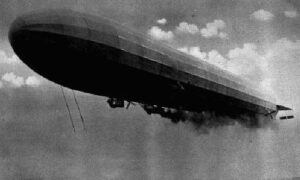

The first power-driven airship was built by a French inventor decades before the Zeppelin was developed by German inventor Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin in 1900. The Zeppelin was a motor-driven rigid airship. The earlier airships were smaller, but Hilter always wanted the most innovative, largest, and deadliest designs of everything, with was likely the reason for the Zeppelin’s size. It was by far the largest airship ever constructed. Hitler didn’t care that size was exchanged for safety. The heavy steel-framed airships were vulnerable to explosion, because they had to be lifted by highly flammable hydrogen gas instead of non-flammable helium gas.

The first power-driven airship was built by a French inventor decades before the Zeppelin was developed by German inventor Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin in 1900. The Zeppelin was a motor-driven rigid airship. The earlier airships were smaller, but Hilter always wanted the most innovative, largest, and deadliest designs of everything, with was likely the reason for the Zeppelin’s size. It was by far the largest airship ever constructed. Hitler didn’t care that size was exchanged for safety. The heavy steel-framed airships were vulnerable to explosion, because they had to be lifted by highly flammable hydrogen gas instead of non-flammable helium gas.

During World War I, the Zeppelins were used as bombers, and the Germans had great success bombing the British Isles with the Zeppelin over the course of 1915 and 1916. The first such  attack on London came on May 31, 1915. That bombing killed 28 people and wounded 60 more. The Germans killed a total of 550 Britons with aerial bombing by May 1916. During one such attack, on September 8, 1915, Heinrich Mathy was the commander of the famed German Zeppelin L13, bombing Aldersgate in central London. His bombs killed 22 people and causing £500,000 worth of damage.

attack on London came on May 31, 1915. That bombing killed 28 people and wounded 60 more. The Germans killed a total of 550 Britons with aerial bombing by May 1916. During one such attack, on September 8, 1915, Heinrich Mathy was the commander of the famed German Zeppelin L13, bombing Aldersgate in central London. His bombs killed 22 people and causing £500,000 worth of damage.

While Mathy was waiting on repairs to his ship, following a bombing run on August 24-25, 1916, he received word that the British had managed for the first time to shoot down a Zeppelin, using incendiary bullets. While he was a fearless pilot, Mathy saw the writing on the wall, and said, “It is only a question of time before we join  the rest. Everyone admits that they feel it. Our nerves are ruined by mistreatment. If anyone should say that he was not haunted by visions of burning airships, then he would be a braggart.” I’m sure he knew that the Zeppelin was a dangerous ship anyway, especially in a crash, but this new danger made matters much worse. As Mathy had predicted, his Zeppelin L31True to his prediction, Mathy’s L31 was shot down during a raid on London on the night of October 1-2, 1916. He is buried in Staffordshire, in a cemetery constructed by the British for the burial of Germans killed on British soil during both World Wars.

the rest. Everyone admits that they feel it. Our nerves are ruined by mistreatment. If anyone should say that he was not haunted by visions of burning airships, then he would be a braggart.” I’m sure he knew that the Zeppelin was a dangerous ship anyway, especially in a crash, but this new danger made matters much worse. As Mathy had predicted, his Zeppelin L31True to his prediction, Mathy’s L31 was shot down during a raid on London on the night of October 1-2, 1916. He is buried in Staffordshire, in a cemetery constructed by the British for the burial of Germans killed on British soil during both World Wars.

We have all heard of the Rolls Royce, and these days it is a car that is close to my heart, not because I own one, but because I’m pretty sure there are family ties to my son-in-law, Travis Royce and now, my daughter, Amy Royce, and their children, Shai and Caalab. I don’t know that for sure, but I have a hunch, and it’s not just the name. Time will tell as I research further.

We have all heard of the Rolls Royce, and these days it is a car that is close to my heart, not because I own one, but because I’m pretty sure there are family ties to my son-in-law, Travis Royce and now, my daughter, Amy Royce, and their children, Shai and Caalab. I don’t know that for sure, but I have a hunch, and it’s not just the name. Time will tell as I research further.

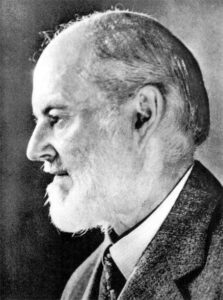

Sir Frederick Henry Royce, 1st Baronet, OBE, was an English engineer. OBE stands for “The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire and is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organizations, and public service outside the civil service.” Sir Royce was famous for his designs of car and aeroplane engines with a reputation for reliability and longevity. Of course, we probably know much more about the product that brought him fame, than we do the man and his partners, who brought that product to life.

Sir Frederick Henry Royce was born in Alwalton, Huntingdonshire, near Peterborough on March 27, 1863, to James and Mary Royce (née King). He was youngest of their five children. His father ran a flour mill which he leased from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. Unfortunately, the business failed, and the family moved to London. After his father died in 1872, Royce had to go out to work selling newspapers and delivering telegrams after only one year of formal schooling. With such a beginning, it would seem quite unlikely that Sir Royce would ever amount to anything, but in 1878 with the financial help of an aunt, Royce  was able to start an apprenticeship with the Great Northern Railway company at its works in Peterborough. Unfortunately, the money ran out after three years, and Royce was again forced to change careers. He worked for a short time with a tool-making company in Leeds, and then returned to London and joined the Electric Light and Power Company. In 1882, he moved to their Liverpool office and began working on street and theatre lighting.

was able to start an apprenticeship with the Great Northern Railway company at its works in Peterborough. Unfortunately, the money ran out after three years, and Royce was again forced to change careers. He worked for a short time with a tool-making company in Leeds, and then returned to London and joined the Electric Light and Power Company. In 1882, he moved to their Liverpool office and began working on street and theatre lighting.

Following a few other ventures that produced minimal success, Royce partnered with Charles Rolls (1877–1910) and Claude Johnson (1864–1926) and founded Rolls-Royce. The new company initially focused on large 40-50 horsepower motor cars, the Silver Ghost and its successors. Royce produced his first aero engine shortly after the outbreak of the First World War and aircraft engines became Rolls-Royce’s principal product. While the Rolls Royce aeroplane engine was a much-needed product during the war, it will always be the famous Rolls Royce automobiles that people will remember. They are beautifully elegant, and to be desired by those who have the means to afford them, as well as those who wish they could afford them.

Henry Royce married Minnie Punt in 1893, but they had no children. The couple separated in 1912. Royce, who lived by the motto “Whatever is rightly done, however humble, is noble,” was appointed OBE in 1918, and was created a baronet, of Seaton in the County of Rutland, in 1930 for his services to British Aviation. Sir Royce’s health began to fail him in 1911 and he was finally forced to leave his factory in the Midlands at Derby. He took a team of designers and moved to the south of England, while spending winters in the south of France. He died at his home in Sussex on April 22, 1933. With no children, the baronetcy became extinct on his death.

If King George III was hoping to keep the New England colonies dependent on the British by placing taxes, restrictions, lockdowns, and the New England Restraining Act on them, he greatly underestimated the colonists. The New England Restraining Act was endorsed by King George III on March 30, 1775. The Act required New England colonies to trade exclusively with Great Britain as of July 1, 1775, with an additional rule going into effect on July 20, banning colonists from fishing in the North Atlantic.

If King George III was hoping to keep the New England colonies dependent on the British by placing taxes, restrictions, lockdowns, and the New England Restraining Act on them, he greatly underestimated the colonists. The New England Restraining Act was endorsed by King George III on March 30, 1775. The Act required New England colonies to trade exclusively with Great Britain as of July 1, 1775, with an additional rule going into effect on July 20, banning colonists from fishing in the North Atlantic.

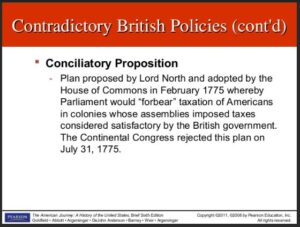

The Restraining Act and the Conciliatory Proposition were introduced to Parliament by British prime minister, Frederick, Lord North, on the same day. The Conciliatory Proposition promised that no colony that met its share of imperial defenses and paid royal officials’ salaries of their own accord would be taxed…a ridiculous statement, because the very act of making the forced payments was basically taxing. Supposedly, the British were  conceding to the colonists’ demand that they be “allowed to provide the crown with needed funds on a voluntary basis.” Through the preposition, Parliament would ask for money through requisitions, not demand it through taxes. If you ask me, that is a distinction without a difference. Either way, the colonists were forced to pay for things they shouldn’t have to. The Restraining Act was meant to appease Parliamentary hardliners, who would otherwise have impeded passage of the pacifying proposition. So, Lord North had to work both sides against the middle to get the Conciliatory Proposition passed.

conceding to the colonists’ demand that they be “allowed to provide the crown with needed funds on a voluntary basis.” Through the preposition, Parliament would ask for money through requisitions, not demand it through taxes. If you ask me, that is a distinction without a difference. Either way, the colonists were forced to pay for things they shouldn’t have to. The Restraining Act was meant to appease Parliamentary hardliners, who would otherwise have impeded passage of the pacifying proposition. So, Lord North had to work both sides against the middle to get the Conciliatory Proposition passed.

Unfortunately for North and prospects for peace, General Thomas Gage had already received orders from London to march on Concord, Massachusetts. His orders were to destroy the armaments stockpiled in the town and take Patriot leaders John Hancock and Samuel Adams into custody. Gage had received the orders in January 1775 and arrived in Boston before the Conciliatory Proposition, meaning that he didn’t know about the  agreement made to stop the taxing of the colonists. So, on April 18, 1775, an army of 700 Redcoats marched towards Concord Bridge. It was basically the last straw…the military action that would lead to the Revolutionary War, the birth of the United States as a new nation, the temporary downfall of Lord North, and the near abdication of King George III. The Treaty of Paris marked the end of the conflict and guaranteed New Englanders the right to fish off Newfoundland. It was the very right denied them by the New England Restraining Act. The British learned that they could only push the colonists so far, and then they would lose control of the very people they tried to enslave.

agreement made to stop the taxing of the colonists. So, on April 18, 1775, an army of 700 Redcoats marched towards Concord Bridge. It was basically the last straw…the military action that would lead to the Revolutionary War, the birth of the United States as a new nation, the temporary downfall of Lord North, and the near abdication of King George III. The Treaty of Paris marked the end of the conflict and guaranteed New Englanders the right to fish off Newfoundland. It was the very right denied them by the New England Restraining Act. The British learned that they could only push the colonists so far, and then they would lose control of the very people they tried to enslave.

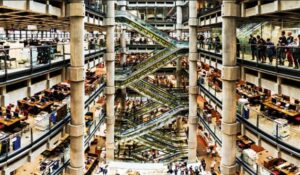

As an insurance agent, I have dealt with Lloyd’s of London many times. They were the company that could handle whatever needed to be handled, when no one else could. They were a no-nonsense company, and that always made me think of a traditional company…if not a stuffy old company filled with old men who almost look down on the people that end up needing insurance from them. Lloyd’s of London is an insurance and reinsurance market located in London, England. Unlike most of its competitors in the industry, it is not an insurance company. Lloyd’s is a corporate body governed by the Lloyd’s Act 1871 and subsequent Acts of Parliament. “Lloyd’s operates as a partially mutualized marketplace within which multiple financial backers, grouped in syndicates, come together to pool and spread risk.”

As an insurance agent, I have dealt with Lloyd’s of London many times. They were the company that could handle whatever needed to be handled, when no one else could. They were a no-nonsense company, and that always made me think of a traditional company…if not a stuffy old company filled with old men who almost look down on the people that end up needing insurance from them. Lloyd’s of London is an insurance and reinsurance market located in London, England. Unlike most of its competitors in the industry, it is not an insurance company. Lloyd’s is a corporate body governed by the Lloyd’s Act 1871 and subsequent Acts of Parliament. “Lloyd’s operates as a partially mutualized marketplace within which multiple financial backers, grouped in syndicates, come together to pool and spread risk.”

While Lloyd’s of London is a traditional company, the building that houses them is…a little strange. The Lloyd’s building, which is also known as the Inside-Out Building. It is located on the former site of East India House in Lime Street. That is in London’s main financial district, the City of London. The building is an example of radical Bowellism architecture in which the services for the building, such as ducts and elevators, are located on the exterior to maximize space in the interior. Whatever they were trying to accomplish, the result is a very strange building. The building is as unique inside as it is outside.

The building was completed in 1986, and in 2011, twenty-five years after its completion the building received Grade I Listing, which is “of exceptional interest and may also have been judged to be of significant national importance.” The Lloyd’s building is the youngest structure ever to obtain Grade I Listing. It is said by Historic England to be “universally recognized as one of the key buildings of the modern epoch.” However, its innovation

of having key service pipes and such routed outside the walls has led to very expensive maintenance costs due to their exposure to the elements. I suppose that makes sense, maybe more sense that the original structure of the building, which while interesting, may not be practical. In fact, Lloyd’s is actually considering a move to a more traditional building. That is almost sad, when you think about it.

of having key service pipes and such routed outside the walls has led to very expensive maintenance costs due to their exposure to the elements. I suppose that makes sense, maybe more sense that the original structure of the building, which while interesting, may not be practical. In fact, Lloyd’s is actually considering a move to a more traditional building. That is almost sad, when you think about it.

As a hiker, I can relate to the draw of a mountain peak, but I was never one to do the winter-ice-climbing-up-a-solid-rock-face type of hiker. I like trail hiking personally, but there are many people who would disagree with me on that. One such hiker/climber was Hudson Stuck, an Alaskan missionary, who on June 7, 1913, led the first successful ascent of Denali…also known as Mount McKinley, before they changed the name. Denali, at 20,320 feet is the highest on the American continent. In fact, there are planes that don’t fly that high…small planes, but nevertheless, they don’t go that high, and would have to fly around Denali.

As a hiker, I can relate to the draw of a mountain peak, but I was never one to do the winter-ice-climbing-up-a-solid-rock-face type of hiker. I like trail hiking personally, but there are many people who would disagree with me on that. One such hiker/climber was Hudson Stuck, an Alaskan missionary, who on June 7, 1913, led the first successful ascent of Denali…also known as Mount McKinley, before they changed the name. Denali, at 20,320 feet is the highest on the American continent. In fact, there are planes that don’t fly that high…small planes, but nevertheless, they don’t go that high, and would have to fly around Denali.

Not crazy enough to try Denali solo, Stuck recruited Harry Karstens, a respected guide, to join his expedition as co-leader. Other members were Walter Harper and Robert G Tatum, both 21, and two student volunteers from the mission school, John Fredson and Esaias George. They departed from Nenana on March 17, 1913. They reached the summit of Denali on June 7, 1913…nearly three months later. Harper, who was of mixed Alaska Native and Scots descent, reached the summit first. Fredson, who was just 14, acted as their base camp manager, hunting caribou and Dall sheep to keep them supplied with food.

There is snow on the mountain year-round, and the air up there is thin, requiring some climbers to bring oxygen. Experienced climbers might be able to climb Denali without oxygen, but sometimes, no matter how fit the body, it can fall victim to the effects of low oxygen…fatigue, hyperventilation, fainting, or worse. So, whether it is needed or not, oxygen is a good idea to have on the trek.

Stuck, who was born in London on November 4, 1863, is an accomplished amateur mountaineer. Mountain climbing, like hiking is an addictive passion, once it takes hold of a person. The feeling you get when you are out there, pushing yourself to new heights or longer hikes, simply can’t be matched in any gym. After moving to the United States, in 1905 Stuck became archdeacon of the Episcopal Church in Yukon, Alaska. His treks across Alaska’s difficult terrain were to preach to villagers and establish schools. His climbing of Denali was more a personal goal than a church oriented one. Stuck was an adventure-seeker, and it was that spirit that drove him to higher heights in every area of his life. And it was that spirit that drove him to the mountain tops…maybe to worship God there too. He was a missionary, after all.

Mount McKinley National Park was established as a wildlife refuge in 1917. Harry Karstens served as the park’s first superintendent. In 1980, the park was expanded and renamed Denali National Park and Preserve.

Encompassing 6 million acres, the park is larger than Massachusetts. In 2015, the mountain was officially renamed Denali. Hudson Stuck died of bronchial pneumonia at Fort Yukon, in his beloved Alaska on October 10, 1920. He was 56 years old. At his request, Stuck, still a British citizen is buried in the local cemetery at Fort Yukon. Today, over 1,000 hopeful climbers attempt to scale Denali each year, with about half of them successfully reaching their goal.

Encompassing 6 million acres, the park is larger than Massachusetts. In 2015, the mountain was officially renamed Denali. Hudson Stuck died of bronchial pneumonia at Fort Yukon, in his beloved Alaska on October 10, 1920. He was 56 years old. At his request, Stuck, still a British citizen is buried in the local cemetery at Fort Yukon. Today, over 1,000 hopeful climbers attempt to scale Denali each year, with about half of them successfully reaching their goal.

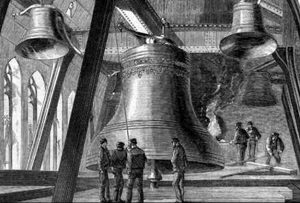

When you think of Big Ben, many of us think of a tower in London…or at least I did. The reality is that Big Ben isn’t the tower at all…it’s the bell. The tower is actually called the Elizabeth Tower…at least since 2012 when it was renamed that in honor of the current Queen Elizabeth. Prior to 2012, the tower was just called “the clock tower.” That was it’s official name, but it was nicknamed Saint Stephen’s tower. It’s funny that we can associate a specific name or idea to something, and have the whole thing totally wrong. The tower name is an interesting story, but that is not the only oddity when it comes to Big Ben.

When you think of Big Ben, many of us think of a tower in London…or at least I did. The reality is that Big Ben isn’t the tower at all…it’s the bell. The tower is actually called the Elizabeth Tower…at least since 2012 when it was renamed that in honor of the current Queen Elizabeth. Prior to 2012, the tower was just called “the clock tower.” That was it’s official name, but it was nicknamed Saint Stephen’s tower. It’s funny that we can associate a specific name or idea to something, and have the whole thing totally wrong. The tower name is an interesting story, but that is not the only oddity when it comes to Big Ben.

As interesting as that was to me, I find it even more interesting to find out that there is actually a prison in the tower. A third of the way, or 114 steps up inside the tower is the Prison Room, where MPs in breach of codes of conduct were imprisoned. The prison room was last used in 1880 when  newly elected MP Charles Bradlaugh, who was an atheist, refused to swear allegiance to Queen Victoria on the Bible. He was kept in the prison room overnight. These days there is a pub named after him in Northampton. I’m not sure how many more people were imprisoned there, but it is certainly a strange use for a clock tower.

newly elected MP Charles Bradlaugh, who was an atheist, refused to swear allegiance to Queen Victoria on the Bible. He was kept in the prison room overnight. These days there is a pub named after him in Northampton. I’m not sure how many more people were imprisoned there, but it is certainly a strange use for a clock tower.

There are 334 steps over 11 floors up to the belfry…399 up to the lantern of the Elizabeth Tower. Each clock face measures 23 feet in diameter. The minute hand on each clock face is 14 feet long, and the hour hand is 9 feet long. The main bell weighs 13.7 tons and is 9 feet in diameter. There are four quarter bells that are smaller. These have different dimensions to enable them to hit different notes. At the top of the tower is an extra light called the Ayrton Light. It was installed so Queen Victoria could see when the members of parliament were sitting after hours.

The current bell is not the original bell. The original bell was famously cast at Whitechapel Bell Foundry. The contract to create the bell went to a company called Warners of Norton in Stockton-on-Tees. A 16.5 ton bell was created and delivered to London before the clock tower was ready. For several months, the bell was tested outside the tower. It was working fine until the man who designed it, Edmund Beckett Denison, decided he  wanted it louder so added a much larger hammer. Three weeks later the bell broke. It was sent to Whitechapel Bell Foundry in pieces and melted down to create the new 13.5 ton bell. Once complete, it took 32 hours to winch it up the tower. Just two months after the bell named Big Ben first went into service in 1859, it was cracked. The hammer that was installed to ring the bell was roughly twice the size it should have been for a bell of that size. Nevertheless, the damage was done. The bell remains flawed to this day. A lighter hammer was fitted, and the bell was rotated slightly so that the hammer no longer hits the cracked section. The clock uses penny weights to keep the time accurate.

wanted it louder so added a much larger hammer. Three weeks later the bell broke. It was sent to Whitechapel Bell Foundry in pieces and melted down to create the new 13.5 ton bell. Once complete, it took 32 hours to winch it up the tower. Just two months after the bell named Big Ben first went into service in 1859, it was cracked. The hammer that was installed to ring the bell was roughly twice the size it should have been for a bell of that size. Nevertheless, the damage was done. The bell remains flawed to this day. A lighter hammer was fitted, and the bell was rotated slightly so that the hammer no longer hits the cracked section. The clock uses penny weights to keep the time accurate.