Limnic Eruption

Natural disasters happen all the time…every day for that matter. Many of these disasters cannot be predicted, or can only be predicted a few minutes to hours before the disaster arrives. That was not the case with the Limnic eruption that happened at Lake Nyos in Cameroon, on August 21, 1986…or was it. A Limnic eruption is a eruption of gas rather than lava or ash, and the gasses can be deadly.

Natural disasters happen all the time…every day for that matter. Many of these disasters cannot be predicted, or can only be predicted a few minutes to hours before the disaster arrives. That was not the case with the Limnic eruption that happened at Lake Nyos in Cameroon, on August 21, 1986…or was it. A Limnic eruption is a eruption of gas rather than lava or ash, and the gasses can be deadly.

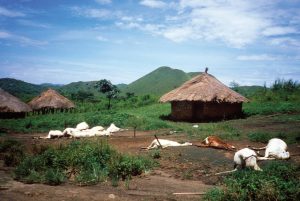

The eruption of lethal gas came from Lake Nyos at 9:30pm on that August day in 1986, took the lives of 2,000 people in the nearby villages, including Lower Nyos. The eruption wiped out four villages too. Carbon Dioxide, while natural to the earth, and even a part of the life process, becomes deadly if there is too much of it. Because Lake Nyos and Lake Monoun are crater lakes, the possibility exists for gasses to escape from the volcanos below them. The lakes are both about a mile square, and are located in the remote mountains of northwestern Cameroon. The area is beautiful with great rock cliffs and lush green vegetation.

Prior to the eruption, there were signs of impending disaster. In August 1984, 37 people near Lake Monoun died suddenly, but the incident was largely covered up by the government. The remoteness and lack of services made the incidents easier to cover up. Since there is no electricity or telephone service in the area, it was not difficult to keep the incident under wraps, and the 5,000 people who lived in villages near Lake Nyos simply had no idea that there was a very real danger of their own lake producing the same dangerous gas. I’m not  certain why they would want to keep the matter a secret, other that to avoid causing a panic, but the plan was fraught with disaster. Had the people known, maybe they could have left the area and survived.

certain why they would want to keep the matter a secret, other that to avoid causing a panic, but the plan was fraught with disaster. Had the people known, maybe they could have left the area and survived.

When scientists first began to be able to predict natural disasters, they were afraid the tell people that there was a problem. Then, after many people lost their lives from what could have been an avoidable disaster, most governments began to see the value of early warnings. The 37 people who lost their lives had no chance of a warning. There were no signs of that eruption, but if the government hadn’t hidden the facts, the 2,000 people who died when lake Nyos had its eruption, might have had a chance. At the very least, they could have made an educated decision about whether to stay or to go. Of course, with two years between the eruptions, they might have ignored the warnings too.

When the rumbling noise from the lake began at 9:30pm, and continued for 15 to 20 seconds, followed by a cloud of carbon-dioxide, and a blast of smelly air, it was too late for those people. The cloud quickly moved north toward the village of Lower Nyos. Some people tried to run away from the cloud, but they were later found dead on the paths leading away from town. The only two survivors of Lower Nyos were a woman and a child. The deadly cloud of gas continued on to Cha Subum and Fang, where another 500 people lost their lives. The carbon dioxide killed every type of animal, including small insects, in its path, but left buildings and plants unaffected, because plants use carbon dioxide as part of the growth cycle.

Reportedly, even survivors experienced coughing fits and vomited blood. Outsiders only learned of the disaster  as they approached the villages and found animal and human bodies on the ground. The best estimate is that 1,700 people and thousands of cattle died. A subsequent investigation of the lake showed the water level to be four feet lower than what it had previously been. Apparently, carbon dioxide had been accumulating from underground springs and was being held down by the water in the lake. When the billion cubic yards of gas finally burst out, it traveled low to the ground–it is heavier than air–until it dispersed. Lake Nyos must now be constantly monitored for carbon-dioxide accumulation. Hopefully that will prevent further disasters like these from happening again.

as they approached the villages and found animal and human bodies on the ground. The best estimate is that 1,700 people and thousands of cattle died. A subsequent investigation of the lake showed the water level to be four feet lower than what it had previously been. Apparently, carbon dioxide had been accumulating from underground springs and was being held down by the water in the lake. When the billion cubic yards of gas finally burst out, it traveled low to the ground–it is heavier than air–until it dispersed. Lake Nyos must now be constantly monitored for carbon-dioxide accumulation. Hopefully that will prevent further disasters like these from happening again.

We have all heard about volcanic eruptions, seen photos or video of one, or maybe even seen one in person. They are an event that makes it hard to take your eyes off of the scene. There are volcanos that erupt often, and there are those that haven’t erupted in hundreds of years. And, there are volcanos that erupt under the ocean. But…there is a rare type of eruption, that is, in fact so rare that it has only been observed twice, although it may have happened elsewhere. It is called a Limnic Eruption.

We have all heard about volcanic eruptions, seen photos or video of one, or maybe even seen one in person. They are an event that makes it hard to take your eyes off of the scene. There are volcanos that erupt often, and there are those that haven’t erupted in hundreds of years. And, there are volcanos that erupt under the ocean. But…there is a rare type of eruption, that is, in fact so rare that it has only been observed twice, although it may have happened elsewhere. It is called a Limnic Eruption.

A limnic eruption, also called a lake overturn, is a rare type of natural disaster in which dissolved carbon dioxide (CO2) gas suddenly erupts from deep lake waters. The eruption forms a gas cloud that can suffocate wildlife, livestock, and humans. It can also cause tsunamis in the lake as the rising CO2 displaces the water. Scientists believe earthquakes, volcanic activity, or explosions can be a trigger for such an explosion. Lakes in which limnic activity occurs are known as limnically active lakes or exploding lakes. Some clues as to limnically active lakes include: CO2 saturated incoming water, a cool lake bottom indicating an absence of direct volcanic interaction with lake waters, an upper and lower thermal layer with differing CO2 saturations, and proximity to areas with volcanic activity, all of which are possible indicators of a limnic lake.

After a Limnic explosion the water left in the lake is filled with debris and massive amounts of dissolved CO2. To date, this phenomenon has been observed only twice. The first was in Cameroon at Lake Monoun in 1984, causing the asphyxiation and death of 38 people living nearby. A second, deadlier eruption happened at neighboring Lake Nyos in 1986, this time releasing over 80 million cubic meters of CO2 and killing around 1,700 people and 3,500 livestock, again by asphyxiation. When the explosion occurred in Lake Nyos, a geyser of water shot out of the lake reaching a height of 300 feet. A small tsunami rushed over the land, followed by a carbon dioxide blast that asphyxiated people up to 15 miles away. Scientists believe limnic explosions are caused by pockets of magma under lakes, which leak and cause carbonic acid to form. In an effort to prevent future explosions, degassing tubes were installed in Lake Nyos to allow the gas to leak at a safe rates.

A third lake, Lake Kivu, on the border between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda, also contains massive amounts of dissolved CO2, and it is believed that Limnic eruptions have occurred there too.  Sample sediments from the lake were taken by professor Robert Hecky from the University of Michigan, which showed that an event caused living creatures in the lake to go extinct approximately every thousand years, and caused nearby vegetation to be swept back into the lake. Limnic eruptions can be measured on a scale using the concentration of CO2 in the surrounding area. Due to the nature of the event, it is hard to determine if limnic eruptions have happened elsewhere. The Messel pit fossil deposits of Messel, Germany, also show evidence of a limnic eruption there. Among the victims of that eruption are perfectly preserved insects, frogs, turtles, crocodiles, birds, anteaters, insectivores, early primates and paleotheres.

Sample sediments from the lake were taken by professor Robert Hecky from the University of Michigan, which showed that an event caused living creatures in the lake to go extinct approximately every thousand years, and caused nearby vegetation to be swept back into the lake. Limnic eruptions can be measured on a scale using the concentration of CO2 in the surrounding area. Due to the nature of the event, it is hard to determine if limnic eruptions have happened elsewhere. The Messel pit fossil deposits of Messel, Germany, also show evidence of a limnic eruption there. Among the victims of that eruption are perfectly preserved insects, frogs, turtles, crocodiles, birds, anteaters, insectivores, early primates and paleotheres.