lawman

Politics can be a touchy subject. Many arguments have come from political disagreements, and in fact, a number of actual fights and even wars have been fought over political disagreements. The Civil War was one sch war fought over political views. During that time there were also a number of private disputes as well. Sumner Pinkham was in volved on one of those disputes. Sumner Pinkham was born in 1820 in the state of Maine and was raised in Wisconsin. Very little, if anything, is known about his early life. He married Laurinda Maria Atwood in Nebraska on November 4, 1842. In 1849, Pinkham joined the California gold rush and then spent time in Oregon before making his way to the booming gold rush camp of Idaho City in 1862. Pinkham was a big man…powerfully built, who stood six feet two inches tall and had a barrel chest. He was also prematurely gray, making him look older than he really was.

Politics can be a touchy subject. Many arguments have come from political disagreements, and in fact, a number of actual fights and even wars have been fought over political disagreements. The Civil War was one sch war fought over political views. During that time there were also a number of private disputes as well. Sumner Pinkham was in volved on one of those disputes. Sumner Pinkham was born in 1820 in the state of Maine and was raised in Wisconsin. Very little, if anything, is known about his early life. He married Laurinda Maria Atwood in Nebraska on November 4, 1842. In 1849, Pinkham joined the California gold rush and then spent time in Oregon before making his way to the booming gold rush camp of Idaho City in 1862. Pinkham was a big man…powerfully built, who stood six feet two inches tall and had a barrel chest. He was also prematurely gray, making him look older than he really was.

Pinkham was a conservative Republican, a Unionist, and an abolitionist, which put him on the opposite side of the majority of Boise Basin mining camps political views, which were predominantly Democrat. When Pinkham arrived in the Idaho City area, Idaho was still a part of Washington Territory, and the Boise Basin was located in Idaho County, of which Florence was the county seat. Florence was located a way away from the new mining basin, so the Washington Legislature established Boise County on January 29, 1863.

After being in the area for a while, and becoming known for his political views, the Governor of Washington was assigning commissioners and officers to the newly established county, and Pinkham was one of them, assigned to serve as the County Sheriff. On March 4, 1863, Congress created Idaho Territory. At that time Boise County exceeded the other counties in both area and in population. Those in office in Boise County at the time, including Pinkham, retained their positions until the territorial government could be officially organized. Pinkham appointed Orlando “Rube” Robbins, who shared his political opinions, as his deputy in August 1863. Robbins would later make himself known as one of Idaho’s greatest lawmen.

By this time, the Civil War was raging back East, and the area miners began to choose sides, around the Union and Confederate causes. This, dueled with whiskey, caused flair-ups between North and South sympathizers, bring with it fist fights, knife fights, and sometimes gun battles as they used force to show their opinions. That kept both Pinkham and his deputy, Rube Robbins, busy breaking up fights and locking up drunken loudmouths as they threatened to fight it out…to the death. The area being predominately Democrat often placed Pinkham at odds with his constituents due to his staunch Unionist views, Republican politics, and tough law enforcement. His list of enemies grew. Nevertheless, both Pinkham’s enemies and his most loyal friends knew that he was a man they shouldn’t mess with when he undertook to enforce the law, which he did with an iron hand.

His greatest enemy was a Southern gunfighter named Ferdinand “Ferd” Patterson. On one occasion, while Patterson was partying with some of his friends in Idaho City, they took unlawful possession of a brewery in Idaho City. Sheriff Pinkham was called by the owner to remove the rowdy group. When Pinkham entered the brewery, he was met with violent resistance. Pinkham and Patterson immediately hated each other. Patterson was Southerner who was crooked by nature, and Pinkham was a Northerner who tended to be self-righteous. In the end, Pinkham was successful, and Patterson was arrested. When Pinkham lost his October 1864 for re-election as Boise County Sheriff, in a bitter contest between the Democratic successionists and Republican candidates. Pinkham was defeated by A O Bowen by a comfortable majority, and Patterson celebrated, as the last of the ballots were being counted. When Patterson encountered his old nemesis, he began rubbing it in. Pinkham, who was in a rage, swung at Patterson, hitting him in the jaw and throwing the gambler off the street and into the gutter. After that, Pinkham walked away. Everyone expected Patterson to retaliate, but he let it go…for then. Pinkham left Idaho City, following the lost election, heading to Illinois to visit his dying mother. When he returned in 1865, everyone figured they would have it out, but it didn’t happen then either.

After the Civil War ended, Pinkham held a huge Fourth of July party. The crowds were mostly festive, with fireworks blazing and booze abundant. The celebration included a brass band, speeches, patriotic songs, a picnic, and a parade with Pinkham leading the way through town. For the victorious Yankees, it was a proud day. But, for the sullen Confederate sympathizers…not so much. To make matters worse, the Yankee’s heckled the “Blue Bellies” throughout the day. Patterson was furious as he watched Pinkham leading the parade through town. Pinkham singing, “Oh, we’ll hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple tree!” was the last straw. Patterson yelled out to the ex-sheriff that if “he didn’t shut his mouth, he’d shut it for him.” Pinkham invited him to try, and he did. A brief fist fight between the two men resulted in the flag falling into the dust of the street. Some witnesses swore they saw Patterson spit on it, and others attested they heard Pinkham swear he would kill Patterson for that, but nothing more came of it at that time. Several weeks later, on Sunday, July 23rd, Pinkham took a hired carriage from Idaho City to the Warm Springs Resort, which was about two miles west of town. Upon his arrival, Pinkham joined a number of his Unionist friends in the saloon, where they were heard singing patriotic and anti-Confederate songs.

Sometime later, Patterson entered the resort while Pinkham was paying his bill. Initially, Patterson ignored Pinkham, but by the time the ex-sheriff exited the resort, Patterson was outside waiting for him. Patterson said the word “draw” and then taunted Pinkham by calling him an “Abolitionist son-of-a-b***h.” Who drew first is in dispute, but in the end, Pinkham was dead. Patterson quickly fled but was immediately followed by several lawmen. Rube Robbins was the first to catch up to him, about 14 miles from Idaho City. Patterson surrendered to Robbins, who turned the killer over to Sheriff Bowen, who was next on the scene. Bowen and his men took over and escorted Patterson back to Idaho City.

A mob wanted to lynch him, and maybe that would have been justice, because in the “sham” trial held in a predominately Democrat area, Patterson was acquitted, and with that, justice for Pinkham would never be served. Ferd Patterson was tried for Pinkman’s murder at the beginning of November 1865. In the six-day trial, defense attorney Frank Ganahl claimed his client acted in self-defense, arguing that Pinkham was lying in wait  for him. Alternatively, Pinkham’s friends testified that he tried to avoid a showdown and that Patterson came to Warm Springs with the explicit purpose of murdering Pinkham. It took only an hour and a half for the jury to acquit Patterson. Pinkham’s funeral was the largest and most impressive funeral ever seen in the mining camp. It was reported that over 1,500 mourners followed his hearse to the graveyard. Meanwhile, knowing he was in extreme danger, Patterson quickly fled Idaho City after his acquittal. He was killed in Walla Walla, Washington, the next year, by Thomas Donahue, an area policeman, in was thought by many to be an assassination. Donahue was charged with the murder of Patterson, but escaped from jail while awaiting trial. There apparently was little interest in tracking him down. He disappeared never to be heard from again.

for him. Alternatively, Pinkham’s friends testified that he tried to avoid a showdown and that Patterson came to Warm Springs with the explicit purpose of murdering Pinkham. It took only an hour and a half for the jury to acquit Patterson. Pinkham’s funeral was the largest and most impressive funeral ever seen in the mining camp. It was reported that over 1,500 mourners followed his hearse to the graveyard. Meanwhile, knowing he was in extreme danger, Patterson quickly fled Idaho City after his acquittal. He was killed in Walla Walla, Washington, the next year, by Thomas Donahue, an area policeman, in was thought by many to be an assassination. Donahue was charged with the murder of Patterson, but escaped from jail while awaiting trial. There apparently was little interest in tracking him down. He disappeared never to be heard from again.

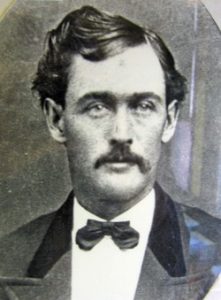

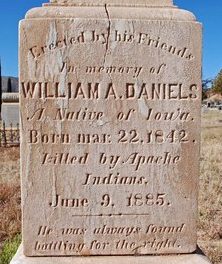

Many men helped to tame the wild west, but unfortunately things didn’t always go exactly as the lawmen planned. Billy Daniels was a pretty typical lawman, but like the thousands of courageous young men and women who helped tame the Wild West, whose names and stories have since been largely forgotten, Billy was not a well remembered lawman. For every Wild Bill Hickok or Wyatt Earp, who have been immortalized by the dramatic exaggerations of dime novelists and journalists, the West had dozens of men like Billy Daniels, who quietly did their duty with little fanfare, celebration, or thanks.

Many men helped to tame the wild west, but unfortunately things didn’t always go exactly as the lawmen planned. Billy Daniels was a pretty typical lawman, but like the thousands of courageous young men and women who helped tame the Wild West, whose names and stories have since been largely forgotten, Billy was not a well remembered lawman. For every Wild Bill Hickok or Wyatt Earp, who have been immortalized by the dramatic exaggerations of dime novelists and journalists, the West had dozens of men like Billy Daniels, who quietly did their duty with little fanfare, celebration, or thanks.

On December 8, 1883, five desperadoes led by Daniel “Big Dan” Dowd, rode into the booming mining town of Bisbee, Arizona. Dowd had heard that the $7,000 payroll of the Copper Queen Mine would be in the vault at the Bisbee General Store. He had planned to surprise the store owners, and make off with the payroll, but things didn’t go exactly as planned. When the outlaws barged into the store with their guns drawn, demanding the payroll, they discovered, to Dowd’s disappointment, that they were too early. The payroll hadn’t arrived yet. The outlaws quickly gathered up what money there was, somewhere between $900 to $3,000, and took valuable rings and watches from the customers who just happened to be in the store. After the robbery, for reasons that are unclear…but possibly, anger…the robbery turned into a slaughter. When the five desperadoes rode away, they left behind four dead or dying people, including Deputy Sheriff Tom Smith and a Bisbee woman named Anna Roberts.

The people of Arizona were stunned. The people had cooperated with the outlaws. There was no reason to kill  those people. The killings were a completely senseless show of brutality. The newspapers called it the “Bisbee Massacre.” The sheriff quickly organized citizen posses to track down the killers, placing Deputy Sheriff Billy Daniels at the head of one. Unfortunately, the posses soon ran out of clues and the trail grew cold. Most of the citizen members gave up, but not Daniels. He stubbornly continued the pursuit alone. Daniels eventually learned the identities of the five men from area ranchers and began to track them down one by one.

those people. The killings were a completely senseless show of brutality. The newspapers called it the “Bisbee Massacre.” The sheriff quickly organized citizen posses to track down the killers, placing Deputy Sheriff Billy Daniels at the head of one. Unfortunately, the posses soon ran out of clues and the trail grew cold. Most of the citizen members gave up, but not Daniels. He stubbornly continued the pursuit alone. Daniels eventually learned the identities of the five men from area ranchers and began to track them down one by one.

Daniels found one of the killers in Deming, New Mexico, and arrested him. He then learned from a Mexican informant that the gang leader, Big Dan Dowd, had fled south of the border to a hideout at Sabinal, Chihuahua. Daniels went under cover, disguising himself as an ore buyer. He tricked Dowd into a meeting and took him prisoner. A few weeks later, Daniels returned to Mexico and arrested another of the outlaws. Other law officers apprehended the remaining two members of the gang. A jury in Tombstone, Arizona, quickly convicted all five men. They were sentenced to be hanged simultaneously. As the noose was fitted around his neck on the five-man gallows, Big Dan reportedly muttered, “This is a regular killing machine.”

Daniels ran for sheriff the net year, but oddly lost. I would think that a hometown hero would be a shoo-in. After all he had done for the town, it would seem that being the sheriff was a thankless job. He found a new  position as an inspector of customs. The job required him to travel all around the vast and often isolated Arizona countryside, where various bands of hostile Apache Indians were a serious danger. Early on the morning of June 10, 1885, Daniels and two companions were riding up a narrow canyon trail in the Mule Mountains east of Bisbee. Daniels, who was in the lead, rode into an Apache ambush. The first bullets killed his horse, and the animal collapsed, pinning Daniels to the ground. Trapped, Daniels used his rifle to defend himself as best he could, but the Apache quickly overwhelmed him and cut his throat. A mere two years after Arizona Deputy Sheriff William Daniels apprehended three of the five outlaws responsible for the Bisbee Massacre, it was an Apache Indians ambush that would end his life. His two companions escaped with their lives and returned the next day with a posse. They found Daniels’ badly mutilated corpse but were unable to track the Apache Indians who murdered him. I guess they lacked Daniels’ under cover or investigative skills.

position as an inspector of customs. The job required him to travel all around the vast and often isolated Arizona countryside, where various bands of hostile Apache Indians were a serious danger. Early on the morning of June 10, 1885, Daniels and two companions were riding up a narrow canyon trail in the Mule Mountains east of Bisbee. Daniels, who was in the lead, rode into an Apache ambush. The first bullets killed his horse, and the animal collapsed, pinning Daniels to the ground. Trapped, Daniels used his rifle to defend himself as best he could, but the Apache quickly overwhelmed him and cut his throat. A mere two years after Arizona Deputy Sheriff William Daniels apprehended three of the five outlaws responsible for the Bisbee Massacre, it was an Apache Indians ambush that would end his life. His two companions escaped with their lives and returned the next day with a posse. They found Daniels’ badly mutilated corpse but were unable to track the Apache Indians who murdered him. I guess they lacked Daniels’ under cover or investigative skills.

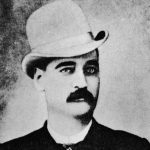

We have long known that my sister, Cheryl Masterson’s family is related to the notorious Bat Masterson…gunfighter, gambler, lawman, and well-known Old West character, but I didn’t really know very much about Bat Masterson. William Barclay “Bat” Masterson was born on November 26, 1853 in Iberville County, Quebec, Canada. His father, Thomas Masterson was born in Canada and by occupation was a farmer. His mother, Catherine McGurk, was an immigrant of Ireland. Bat was the second child in a family of five brothers and two sisters. They were raised on farms in Quebec, New York, and Illinois, until they finally settled near Wichita, Kansas in 1871. During his boyhood years he became an expert in the use of firearms, and accompanied expeditions that went out to hunt buffalo.

We have long known that my sister, Cheryl Masterson’s family is related to the notorious Bat Masterson…gunfighter, gambler, lawman, and well-known Old West character, but I didn’t really know very much about Bat Masterson. William Barclay “Bat” Masterson was born on November 26, 1853 in Iberville County, Quebec, Canada. His father, Thomas Masterson was born in Canada and by occupation was a farmer. His mother, Catherine McGurk, was an immigrant of Ireland. Bat was the second child in a family of five brothers and two sisters. They were raised on farms in Quebec, New York, and Illinois, until they finally settled near Wichita, Kansas in 1871. During his boyhood years he became an expert in the use of firearms, and accompanied expeditions that went out to hunt buffalo.

In the Fall of 1871, when Bat was 18 years old, he and his 19 year old brother, Ed decided to head west to Kansas, looking for adventure by hunting buffalo. During this time, they camped with hunters working along the Salt Fork River in what is present day Comanche and Barber Counties in Kansas. It was during their visits to other buffalo hunting camps that the brothers met several men who would also become legends in western history, including Wyatt Earp, Billy Dixon, Tom Nixon, and “Prairie Dog” Dave Morrow.

Bat Masterson was one of the very few who lived during the lawless days of the Old West who wasn’t there to make a name for himself, or to count the notches on his belt. In reality, he was a genuine and honest man, who didn’t have a reputation for violence, but was loyal to the end, and would defend his friends, if necessary. The nickname “Bat” was given to him by his companions one day while out on one of these hunting trips, the name coming from Baptiste Brown, or “Old Bat,” whose fame as a leader, hunter, and trapper was well known in the generation that preceded Masterson upon the Western stage.

In the summer of 1872, Bat and Ed worked on a construction crew that was expanding the Santa Fe railroad to Colorado. That winter, they returned to buffalo hunting and were joined by their younger brother, Jim in their camp along Kiowa Creek southeast of Dodge City. In January, 1873, the Masterson brothers gave up buffalo hunting. Bat remained in Dodge City, but his brothers returned to the family farm in Sedgwick County, Kansas. Ed, after deciding that farming really wasn’t for him, was soon back in Dodge…just a month later, in fact. Ed went to work in the Alhambra Saloon. For a time, Bat returned to buffalo hunting, but the number of buffalo were becoming fewer and fewer. By 1874, the vast numbers of buffalo roaming Kansas had been slaughtered, so many of the hunters moved south and west into what was hostile Indian Territory.

While this venture would prove profitable, the Indians tribes in the area correctly perceived the post and the buffalo hunting as a major threat to their existence and attacks were being made on some buffalo hunters. The hostile environment didn’t stop Adobe Walls saloon owner, James Hanrahan, from leading a party of Dodge City buffalo hunters, including Bat Masterson, southward on June 5, 1874. Along the way, a band of Cheyenne Indians ran off their cattle stock about 75 miles southwest of Dodge City. The hunters soon joined a wagon train en route to Adobe Walls, arriving just hours before the Indian attack, known as the Second Battle of Adobe Walls, took place.

Early in the morning of June 27, 1874, a combined force of some 700 Comanche, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Arapaho warriors, led by Comanche Chief Quanah Parker and Isa-tai, attacked the buffalo camp. The 28 men, including Bat Masterson and Billy Dixon, took refuge in the two stores and the saloon. Despite being dramatically outnumbered, the hunters’ superior weapons repelled the Indian assault. After four days of continuous battle, about 100 men arrived to reinforce the post and the Indians soon retreated. Loss numbers vary, but as many as 70 Indians were killed and many others, including Parker, were wounded. The men at Adobe Walls suffered four fatalities.

Of course, the attacks brought retaliation in the form of an expedition against the Indians of the Texas Panhandle in what would become known as the Red River War. Masterson joined the expedition that was order by Colonel Nelson A. Miles, as a civilian scout and a teamster working out of Fort Elliot in what was then called Sweetwater, Texas (now Mobeetie). However, the next spring he was back to buffalo hunting and spending time at his friend Charlie Rath’s store, located about five miles from the fort, which had become the “headquarters” for the buffalo hunters. He was also a frequent visitor to the many saloons in the area. By early 1876, he was working as a faro dealer in Henry Fleming’s Saloon.

On January 24th, he became embroiled in an argument with Sergeant Melvin A. King over a card game and a dance hall beauty named Mollie Brennan. The argument quickly led to a gunplay and King was left dead. However, in the melee, King’s shot passed through Mollie Brennan’s body, killing her, and then hit Masterson in the pelvis. The injury caused Bat to walk with a limp for the rest of his life. After he recovered, Masterson returned to Dodge City, Kansas where he became a lawman along with his friend Wyatt Earp under Ford County Sheriff, Charles Bassett. These were the years that Dodge City was known as a “wicked little town.” Cattle drives had replaced the buffalo hunters as longhorn cattle were driven up from Texas along the western branch of the Chisholm Trail to the railroad. For the next ten years, over 5 million head were driven on the trail into Dodge City.

In July, 1877, Bat was appointed under-sheriff of Ford County under Sheriff Charlie Bassett. That very same month, his brother Ed Masterson became an assistant marshal in Dodge City. Just a few months later, in October, Bat announced in the Dodge City Times that he was a candidate for sheriff of Ford County, stating: “At the earnest request of many citizens of Ford County, I have consented to run for the office of sheriff, at the coming election in this county. While earnestly soliciting the suffrages of the people, I have no pledges to make, as pledges are usually considered, before election, to be mere clap-trap. I desire to say to the voting public that I am no politician and shall make no combinations that would be likely to, in anywise, hamper me in  the discharge of the duties of the office, and, should I be elected, will put forth my best efforts to so discharge the duties of the office that those voting for me shall have no occasion to regret having done so. Respectfully, W. B. Masterson.”

the discharge of the duties of the office, and, should I be elected, will put forth my best efforts to so discharge the duties of the office that those voting for me shall have no occasion to regret having done so. Respectfully, W. B. Masterson.”

Masterson never again fought a gun battle in his life after the battle with King, but the story of the Dodge City shootout and his other exploits ensured Masterson’s lasting fame as an icon of the Old West. He spent the next four decades of his life working as sheriff, operating saloons, and eventually trying his hand as a newspaperman in New York City. The old gunfighter finally died of a heart attack in October 1921 at his desk in New York City. He had certainly lived an interesting life.

Growing up, my sisters and I watched lots of westerns. It wasn’t so strange really, because westerns were the in thing back then. Everyone loved watching them. One show I remember watching was The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. It all seemed like it took place so long ago, and to many people I guess it was. Still, when you think of the fact that Wyatt Earp, a frontiersman, marshal and gambler, who got into a feud in Tombstone, Arizona, that led to the famous gunfight at the O.K. Corral passed away quietly in Los Angeles on January 13, 1929, it doesn’t seem so long ago anymore. I guess that in Wyatt Earp’s case, old gunfighters never die, they just lose their fight. Wyatt Earp was born on March 19, 1848, and that seems long ago. The gunfight took place on October 26, 1881…and Wyatt Earp survived. He had led such a wild life, that the thought of him ending up dying quietly in Los Angeles seemed…well, just too tame, and just too much a part of modern times to be right. Nevertheless, it was right. He did live in modern times, and in fact was a friend of John Wayne’s.

Growing up, my sisters and I watched lots of westerns. It wasn’t so strange really, because westerns were the in thing back then. Everyone loved watching them. One show I remember watching was The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. It all seemed like it took place so long ago, and to many people I guess it was. Still, when you think of the fact that Wyatt Earp, a frontiersman, marshal and gambler, who got into a feud in Tombstone, Arizona, that led to the famous gunfight at the O.K. Corral passed away quietly in Los Angeles on January 13, 1929, it doesn’t seem so long ago anymore. I guess that in Wyatt Earp’s case, old gunfighters never die, they just lose their fight. Wyatt Earp was born on March 19, 1848, and that seems long ago. The gunfight took place on October 26, 1881…and Wyatt Earp survived. He had led such a wild life, that the thought of him ending up dying quietly in Los Angeles seemed…well, just too tame, and just too much a part of modern times to be right. Nevertheless, it was right. He did live in modern times, and in fact was a friend of John Wayne’s.

I’m not sure why that whole scenario struck me as odd. Wyatt Earp was 80 years old at the time of his passing…not an overly excessive amount of years…average, in fact. Since he was born in 1848, his passing in  1929 would be right. I guess that the thing that seemed strange to me was the fact that when Wyatt Earp passed away, my own dad was five years old. Yes, he was an old man, and my dad a young boy, but for those five years, their life spans occupied the same space in history. And yet, my dad’s life had no connection to the time of Wyatt Earp, or to the man that he was.

1929 would be right. I guess that the thing that seemed strange to me was the fact that when Wyatt Earp passed away, my own dad was five years old. Yes, he was an old man, and my dad a young boy, but for those five years, their life spans occupied the same space in history. And yet, my dad’s life had no connection to the time of Wyatt Earp, or to the man that he was.

Wyatt Earp was a boy in search of adventure, and ran away from home twice after the Civil War broke out when he was 13. He went to join up with his two older brothers, Virgil and James. Each time he ran away, he was caught before he could reach the battlefield, and he was sent back home. Finally, at the age of 17, he left for good. His family had moved from the Illinois farm to California, but Wyatt wanted adventure, so he headed out to seek his own idea of life. He worked many different jobs, most notably as a lawman, and of course, a gambler. Life was not kind to Wyatt Earp. At a point when he was finally ready to settle down with the woman he loved, he married Urilla Sutherland, the daughter of the local hotel owner. The couple married about 1870, built a house in town, and were excitedly awaiting the birth of their first child. Then, life hit him with it’s most  cruel blow. Within a year of their marriage Urilla contracted Typhus and died, along with their unborn child. Wyatt went off the deep end and became wild again. Eventually, he would be suspected of killing one of the suspects in his brother, Morgan’s death.

cruel blow. Within a year of their marriage Urilla contracted Typhus and died, along with their unborn child. Wyatt went off the deep end and became wild again. Eventually, he would be suspected of killing one of the suspects in his brother, Morgan’s death.

Unfortunately…or maybe fortunately, the west began to settle down. Wyatt was getting older. He settled in Los Angeles and hoped to have the Old West and his own legacy portrayed in film, but Hollywood wasn’t interested until after his death. I suppose it was then that Westerns moved into the forefront of television and movies. Westerns would then have a long run of popularity in the homes of many people…ours included.