kentucky

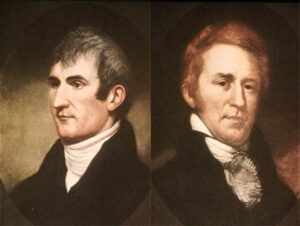

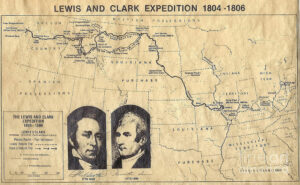

Exploration of new worlds is a journey that always has the potential to end in loss of life, and even disaster. The Corps of Discovery, also known as the Lewis and Clark expedition, was no different. The expedition was proceeding as planned, except for the fact that Sergeant Charles Floyd was feeling ill. The expedition left Saint Louis the previous May, enroute up the Missouri River with a party of 35 men, called the Corps of Discovery. Floyd was a native of Kentucky who had enlisted in the US military a few years earlier. When he heard that there was a call for volunteers to join the ambitious expedition across the continent to the Pacific, Floyd was one of the first men to apply. Floyd was the perfect choice for the program. He was young, vigorous, and better educated than most of the soldiers. The two co-captains not only selected him to join the mission, but they also promoted him to sergeant.

Exploration of new worlds is a journey that always has the potential to end in loss of life, and even disaster. The Corps of Discovery, also known as the Lewis and Clark expedition, was no different. The expedition was proceeding as planned, except for the fact that Sergeant Charles Floyd was feeling ill. The expedition left Saint Louis the previous May, enroute up the Missouri River with a party of 35 men, called the Corps of Discovery. Floyd was a native of Kentucky who had enlisted in the US military a few years earlier. When he heard that there was a call for volunteers to join the ambitious expedition across the continent to the Pacific, Floyd was one of the first men to apply. Floyd was the perfect choice for the program. He was young, vigorous, and better educated than most of the soldiers. The two co-captains not only selected him to join the mission, but they also promoted him to sergeant.

Unfortunately, Floyd’s perfect attributes could not keep him from becoming ill. As a result, his part in the great voyage of the Corps of Discovery was short-lived. In their journal, Lewis and Clark reported in July that Floyd  “has been very sick for several days. Then it appeared that he was getting better…for a time anyway. On August 15, he was “seized with a complaint somewhat like a violent chorlick [colic]… [and] he was sick all night.” The two captains were very concerned, and did what they could for Floyd, but they were far from what little medical help might have been available in 1804. Nevertheless, Floyd continued to grow weaker.

“has been very sick for several days. Then it appeared that he was getting better…for a time anyway. On August 15, he was “seized with a complaint somewhat like a violent chorlick [colic]… [and] he was sick all night.” The two captains were very concerned, and did what they could for Floyd, but they were far from what little medical help might have been available in 1804. Nevertheless, Floyd continued to grow weaker.

By August 19, 1804, Floyd’s illness was growing very severe during, and Clark sat up with the suffering man almost the entire night. Unfortunately, other than being with Floyd at the end, there was nothing that could be done. Floyd died in the early afternoon of August 19th, reportedly “with a good deal of composure.” The members of the expedition buried Floyd’s body on a high bluff overlooking a river that flowed into the Missouri. At the site, they placed a red-cedar post with his name, title, and date of death over the grave. Lewis read the funeral service, and the two captains concluded the ceremony by naming the nearby stream Floyds River and the hill Floyds Bluff in honor of their young comrade.

Lewis and Clark always regretted that they possessed such limited wilderness medical skills, because they were unable to cure the young soldier. Still, even if Floyd had been in Philadelphia, it is unlikely that the best doctors of the day would have been able to save him. From the journal telling of the symptoms, it is likely that Floyd

was suffering from acute appendicitis. His condition grew worse and worse, and when his appendix ruptured, he died quickly of peritonitis. Without modern antibiotic, and without the knowledge we have today of proper surgical procedures, there was simply no hope. Amazingly, Floyd’s was the only death the Corps of Discovery suffered in more than two years of dangerous wilderness travel. On their return journey from the Pacific in 1806, after a successful expedition, Lewis and Clark stopped at Sergeant Floyd’s grave to pay their respects.

was suffering from acute appendicitis. His condition grew worse and worse, and when his appendix ruptured, he died quickly of peritonitis. Without modern antibiotic, and without the knowledge we have today of proper surgical procedures, there was simply no hope. Amazingly, Floyd’s was the only death the Corps of Discovery suffered in more than two years of dangerous wilderness travel. On their return journey from the Pacific in 1806, after a successful expedition, Lewis and Clark stopped at Sergeant Floyd’s grave to pay their respects.

While most people look back on their childhood with fond memories, most of us would say our childhood was probably typical for the era we lived in. Of course, not every childhood is perfect, and some can be absolutely horrible. President Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1890, and spent his childhood years in Kentucky and Indiana. He personally summed up his childhood days on the frontier as “the short and simple annals of the poor.” While that is how Lincoln saw his childhood, he wasn’t the only one in that situation. The hardships he endured there as a child weren’t unique. Frontier life was harsh for most families in the early 1800s. Living and working on the frontier was hard work. In fact, sometimes the people worked as hard as their oxen and horses. According to Lincoln, his earliest memories were of life on the farm in Kentucky where he moved in 1811 with his parents, Thomas and Nancy, and sister, Sarah. She was four years old, and Abraham was two years old. His parents had been married five years.

While most people look back on their childhood with fond memories, most of us would say our childhood was probably typical for the era we lived in. Of course, not every childhood is perfect, and some can be absolutely horrible. President Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1890, and spent his childhood years in Kentucky and Indiana. He personally summed up his childhood days on the frontier as “the short and simple annals of the poor.” While that is how Lincoln saw his childhood, he wasn’t the only one in that situation. The hardships he endured there as a child weren’t unique. Frontier life was harsh for most families in the early 1800s. Living and working on the frontier was hard work. In fact, sometimes the people worked as hard as their oxen and horses. According to Lincoln, his earliest memories were of life on the farm in Kentucky where he moved in 1811 with his parents, Thomas and Nancy, and sister, Sarah. She was four years old, and Abraham was two years old. His parents had been married five years.

At Knob Creek, in Kentucky, the Lincoln family lived in a one-room cabin with a dirt floor. The place was very similar to the place where Lincoln was born a mere nine miles way near Hodgenville. Steep, heavily wooded hills rose on each side of the home. Nevertheless, things were “looking up” on the Knob Creek farm, because while the place was leased, Lincoln’s father planted corn and pumpkins on wide fields with rich soil on the 30-acre farm. From the little dirt-floor cabin on the road from Louisville to Nashville, the Lincoln family watched as the “world passed” by. Pioneers with fully loaded wagons, peddlers, local politicians, slaves, missionaries and soldiers returning from the War of 1812.

Abraham’s dad, Thomas Lincoln, who was stern and often domineering, put his son to work before he turned seven. Of course, if you ask me, seven-year-olds can help out, provided that they aren’t mistreated in the process. Abraham filled the wood box, brought water from the creek, weeded the garden, gathered grapes for wine and jelly, picked persimmons for beer making and planted pumpkin seeds.

Lincoln didn’t have many opportunities to go to school, as was common in those days in rural Kentucky. For the most part he was self-taught. Mostly, he and his sister sporadically attended ABC schools—so-called “blab” schools in which students repeated their teacher’s oral lessons aloud. Usually barefoot, Lincoln walked to the one-room schoolhouse, “a little log room about 15 feet square, with a fireplace at one side.”

Two years later, Abraham’s mother, Nancy Lincoln died in the remote wilderness—the first of Lincoln’s many family tragedies. Nancy was a good mother, and her passing was heartbreaking for the Lincoln children. Apparently, she had consumed milk tainted when cows ate poisonous white snakeroot…although, some believed the cause of death was tuberculosis. She was just 34 years old. Eleven-year-old Sarah now became the woman of the house, and all domestic duties fell to her. The Lincoln children’s lives were worse than ever. That winter, the motherless children and their 19-year-old orphan cousin lived dismally in that place.

It didn’t take Thomas long to decide that he needed a new wife, so Thomas Lincoln traveled to Elizabethtown, Kentucky, where he proposed to widow Sarah Bush Johnston, whom he had known since childhood. She accepted, provided Lincoln paid off her debts. On December 2, 1819, Thomas and Sarah married and later returned to Little Pigeon Creek, accompanied by her three children: Elizabeth, 13; Matilda, 10; and John, 9. Thomas’s new wife brought along furniture (including a walnut bureau valued at $50), cooking utensils and comfortable bedding…astonishing luxuries for her new stepchildren. She also brought several books, including the Bible and Aesop’s Fables, which she gifted to Abe. Things were looking up again in the Lincoln household. At his wife’s insistence, Thomas Lincoln installed a cabin floor and plastered cracks between logs. Instead of cornhusks, Abraham and his sister slept on a feather bed. The cramped conditions were no match for the love Sarah brught with her, and the family thrived. To make him look “more human,” Lincoln’s stepmother dressed up the poorly clad Abraham.

On the farm, Lincoln became skillful with an ax. But Thomas didn’t see the need for the reading his son loved.  He wanted him to learn carpentry, but Abraham wasn’t interested, and the matter brought tension to the relationship. Sometimes the illiterate Thomas even reprimanded Abraham for reading instead of doing farm chores. Thankfully, Sarah Bush Lincoln persuaded her husband to allow their son to read and study. “At first, he was not easily reconciled to it,” she recalled, “but finally he too seemed willing to encourage him to a certain extent.” The bond between stepmother and stepson grew. Sarah Bush Lincoln recalled years later, “Abe was the best boy I ever saw.” I think we would a have to agree, he was not just a good boy, but a great man and a great president.

He wanted him to learn carpentry, but Abraham wasn’t interested, and the matter brought tension to the relationship. Sometimes the illiterate Thomas even reprimanded Abraham for reading instead of doing farm chores. Thankfully, Sarah Bush Lincoln persuaded her husband to allow their son to read and study. “At first, he was not easily reconciled to it,” she recalled, “but finally he too seemed willing to encourage him to a certain extent.” The bond between stepmother and stepson grew. Sarah Bush Lincoln recalled years later, “Abe was the best boy I ever saw.” I think we would a have to agree, he was not just a good boy, but a great man and a great president.

Following instructions and paying close attention to those instructions are crucial to the safe operation of a plane, especially at take offs and landings. When the pilot of Comair Flight 5191 taxied to the runway of his takeoff, something went horribly wrong. He was told to proceed to Runway 22, but he turned one lane too early, and ended up taking off on Runway 26, which was too short for a safe take off of a plane of that size. Comair 1591, was a CRJ-100ER plane that was carrying 47 passengers and 3 crew members. Instead of using runway 22 as expected, they used runway 26 which had too short of a path for a safe takeoff, even though Captain Jeffrey Clay confirmed using runway 22. He inadvertently took a left too early according to the map. At Blue Grass Airport in Lexington, Kentucky, on August 27, 2006, 49 of the 50 passengers and crew died while taking off from the airport. It’s hard to say at what point the pilot knew he was in trouble, but as the plane reached the end of the runway, they knew that there had not been enough time to gt the plane up to speed,and they simply couldn’t get enough lift to get it safely in the air. “They must have almost cleared the fence because only the top of it was missing and then the tips of some trees further out were also burnt off,” said Nick Bentley, who owns the 115-acre farm where the plane crashed, referring to an 8-foot metal fence that separates his property from the airport’s 3,500-foot runway.

Following instructions and paying close attention to those instructions are crucial to the safe operation of a plane, especially at take offs and landings. When the pilot of Comair Flight 5191 taxied to the runway of his takeoff, something went horribly wrong. He was told to proceed to Runway 22, but he turned one lane too early, and ended up taking off on Runway 26, which was too short for a safe take off of a plane of that size. Comair 1591, was a CRJ-100ER plane that was carrying 47 passengers and 3 crew members. Instead of using runway 22 as expected, they used runway 26 which had too short of a path for a safe takeoff, even though Captain Jeffrey Clay confirmed using runway 22. He inadvertently took a left too early according to the map. At Blue Grass Airport in Lexington, Kentucky, on August 27, 2006, 49 of the 50 passengers and crew died while taking off from the airport. It’s hard to say at what point the pilot knew he was in trouble, but as the plane reached the end of the runway, they knew that there had not been enough time to gt the plane up to speed,and they simply couldn’t get enough lift to get it safely in the air. “They must have almost cleared the fence because only the top of it was missing and then the tips of some trees further out were also burnt off,” said Nick Bentley, who owns the 115-acre farm where the plane crashed, referring to an 8-foot metal fence that separates his property from the airport’s 3,500-foot runway.

Shortly after 6am, Comair flight 1591 crashed in a field just half a mile from the Blue Grass Airport in an area of Kentucky known for its horse farms and the Keeneland Race Course. The plane was traveling from Lexington to Atlanta, when it went down. Peggy Young, who lives on Rice Road, near the area where the plane came down, said that just after 6am she and her husband Michael were awakened by the sound of the crash. “There was a loud explosion,” she said in a telephone interview. “We thought it was just a storm, but then we thought it was too loud to be a storm because it had just barely rained. We just were sleeping in when the phone rang and it was Keeneland security and they told my husband there had been an airplane crash.”

First Officer James Polehinke was the only survivor of the crash. He suffered broken bones, a collapsed lung,

and severe bleeding. In the end, the ultimate blame was put on the captain, because he didn’t abort liftoff despite questioning his surroundings. Nevertheless, the airport was found to be using outdated maps and had needed to improve runway markings and conditions.So in reality there was blame to go around, and because of the errors, 49 people lost their lives that day in August, twelve years ago. “The whole airport shut down from Aug. 18 to 20,” said Brian Ellestad, the director of marketing and community relations.

and severe bleeding. In the end, the ultimate blame was put on the captain, because he didn’t abort liftoff despite questioning his surroundings. Nevertheless, the airport was found to be using outdated maps and had needed to improve runway markings and conditions.So in reality there was blame to go around, and because of the errors, 49 people lost their lives that day in August, twelve years ago. “The whole airport shut down from Aug. 18 to 20,” said Brian Ellestad, the director of marketing and community relations.

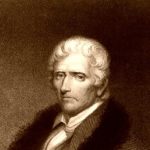

I grew up in a time when western shows were all the rage on television. One show that my family always watched was Daniel Boone. Most people know Daniel Boone from their history classes, as an American frontiersman. Most of his fame stemmed from his exploits during the exploration and settlement of Kentucky. Boone arrived in Kentucky in 1767, about 25 years before it became a state on June 1, 1792. He spent the next 30 years exploring and settling the lands of Kentucky, including carving out the Wilderness Road and building the settlement station of Boonesboro. Without Boone the history of Kentucky would have been much different.

I grew up in a time when western shows were all the rage on television. One show that my family always watched was Daniel Boone. Most people know Daniel Boone from their history classes, as an American frontiersman. Most of his fame stemmed from his exploits during the exploration and settlement of Kentucky. Boone arrived in Kentucky in 1767, about 25 years before it became a state on June 1, 1792. He spent the next 30 years exploring and settling the lands of Kentucky, including carving out the Wilderness Road and building the settlement station of Boonesboro. Without Boone the history of Kentucky would have been much different.

Boone was born near Reading, in Berks County, Pennsylvania, the son of hard-working but adventurous Quaker parents. He learned some blacksmithing, but had very little formal education. Daniel appears to have been a scrappy lad who loved hunting, the wilderness, and independence. When his parents left Pennsylvania in 1750 bound for the Yadkin valley of northwest North Carolina, Daniel went along willingly, because the move fit right in with his spirit of adventure.

Upon arriving in North Carolina, the cutting edge of the frontier, he was able to indulge his hunting prowess and love of the wilderness. In the years that followed, he served as a wagoner with General Edward Braddock’s ill-fated expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755. Boone then married a neighbor’s daughter, Rebecca Bryan, in 1756, and in 1758 is believed to have been a wagoner with General John Forbes who was hacking out the road to Fort Duquesne, which he rebuilt as Fort Pitt…now Pittsburgh. Back in North Carolina, Daniel purchased land from his father but never seriously engaged in farming. He loved to roam far too much to settle down and farm the land in one place. In 1763 he and his brother Squire journeyed to Florida, but for unknown reasons they did not stay. I guess Kentucky would always be his first love.

Boone was first in eastern Kentucky in 1767, but his expedition of 1769-1771 is more widely known. With a small party Boone advanced along the Warrior’s Path into a beautiful garden-like region. When the time came for the party to return he remained behind in the wilderness until March 1771. On the way home, he and his brother were robbed by Indians of their deer skins and pelts, but the two remained exuberant over the land known as “Kentuck.”

So much did Daniel love that “dark and bloody ground” that he tried to return in 1773, taking forty settlers with him, but the Indians drove them back. The next year he went again into the region carrying a warning of Indian troubles to Governor John Murray Dunmore’s surveyors. As Judge Richard Henderson was concluding the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals. in March 1775, by which much of Kentucky was sold to his Transylvania Company, Boone was hacking out the Wilderness Road. As soon as he reached his destination, he began building Boonesboro, one of several stations, or forts under construction at that time. For the next four years…through 1778…Boone was a captain in the militia, and was busy defending the settlements. His leadership  helped save the three remaining Kentucky stations, Boonesboro, Logan’s (St. Asaph’s), and Harrodsburg. These were years of many ambushes; such as Blue Licks in 1778; captures, including Boone, himself, who was was captured but escaped from the Shawnees; rescues, and desperate defenses.

helped save the three remaining Kentucky stations, Boonesboro, Logan’s (St. Asaph’s), and Harrodsburg. These were years of many ambushes; such as Blue Licks in 1778; captures, including Boone, himself, who was was captured but escaped from the Shawnees; rescues, and desperate defenses.

I knew and have learned much about Daniel Boone over the years, but for me the most interesting thing I have learned is that Daniel Boone is my 5th Cousin 8 times removed, on the Pattan side of my mother, Collene Spencer’s family. It is a small, small world. Today is Daniel Boone Day. It is a day to remember all this great man did for our country.

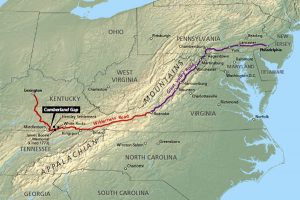

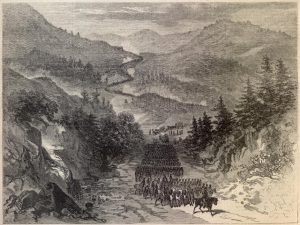

In 1775, Daniel Boone blazed a trail through the Cumberland Gap…a notch in the Appalachian Mountains located near the intersection of Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee…through the interior of Kentucky and to the Ohio River. That might not seem like such a big deal, but the trail, which became known as the Wilderness Road, would serve as the pathway to the western United States for some 300,000 settlers over the next 35 years. The path that Boone pioneered led to the establishment of the first settlements in Kentucky, including Boonesboro; and to Kentucky’s admission to the Union as the 15th state in 1792. Of course, Daniel Boone wasn’t the first human being to ever use the trail. The earliest origins of the Wilderness Road were the trails, created by the great herds of buffalo that once roamed the region. Then came the Native American tribes such as the Cherokee and Shawnee, who used the trails to make attacks on each other. They called the trail the Athowominee, which means “Path of the Armed Ones” or “The Great Warrior’s Path.” In 1673, a young man named Gabriel Arthur, became the first white settler known to have crossed through the Cumberland Gap using part of what would become the Wilderness Road. Of course, it wasn’t his choice to go. The Shawnee warriors captured Arthur and forced him to go with them, before releasing him later. I’m quite sure he would have gladly forgone the honor of being the first white man on the trail, if it meant that he would not be taken prisoner.

In 1775, Daniel Boone blazed a trail through the Cumberland Gap…a notch in the Appalachian Mountains located near the intersection of Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee…through the interior of Kentucky and to the Ohio River. That might not seem like such a big deal, but the trail, which became known as the Wilderness Road, would serve as the pathway to the western United States for some 300,000 settlers over the next 35 years. The path that Boone pioneered led to the establishment of the first settlements in Kentucky, including Boonesboro; and to Kentucky’s admission to the Union as the 15th state in 1792. Of course, Daniel Boone wasn’t the first human being to ever use the trail. The earliest origins of the Wilderness Road were the trails, created by the great herds of buffalo that once roamed the region. Then came the Native American tribes such as the Cherokee and Shawnee, who used the trails to make attacks on each other. They called the trail the Athowominee, which means “Path of the Armed Ones” or “The Great Warrior’s Path.” In 1673, a young man named Gabriel Arthur, became the first white settler known to have crossed through the Cumberland Gap using part of what would become the Wilderness Road. Of course, it wasn’t his choice to go. The Shawnee warriors captured Arthur and forced him to go with them, before releasing him later. I’m quite sure he would have gladly forgone the honor of being the first white man on the trail, if it meant that he would not be taken prisoner.

Another expedition, led by Dr Thomas Walker set out in 1750, from Virginia with the aim of exploring lands further west for potential settlement. Discouraged by the rough terrain in southeastern Kentucky, the group turned back, but Walker’s detailed report of the expedition proved to be an invaluable resource for later expeditions, including Boone’s. Having hiked some pretty tough trails, I can say that I can understand the idea of turning back. I’ve never turned back on a trail, but then I’m not camping out on my trails either. Freezing cold in the nights and searing heat in the daytime, could make for a very rough trip.

In 1773, Boone attempted to lead his family and several others to settle in Kentucky, but Cherokee Indians attacked the group, and two of the would-be settlers, including Boone’s son James, were killed. Two years later, a group of wealthy investors headed up by Judge Richard Henderson of North Carolina formed the Transylvania Company, to colonize the rich lands around the Kentucky River and establish Kentucky as the 14th colony. They decided to hire Boone, who’s knowledge of the existing trails was well known, to blaze a new trail through the Cumberland Gap. Henderson decided to approach the Cherokee directly, and in March 1775 his associates negotiated with the Cherokee to purchase the land between the Cumberland and Kentucky rivers, a total of some 20 million acres, for 10,000 pounds of goods.

On March 10, 1775, Boone and around 30 other ax-wielding road cutters, including his brother and son-in-law, set off from the Long Island of Holston River, a sacred Cherokee treaty site located in present day Kingsport, Tennessee. From there they traveled north along a portion of the Great Warrior’s Path, heading through Moccasin Gap in the Clinch Mountains. They Avoided Troublesome Creek, which had plagued previous travelers along the route, and crossed the Clinch River, near what is now Speers Ferry, Virginia. Then they followed Stock Creek, crossed Powell Mountain through Kane’s Gap and headed into the Powell River Valley. About 20 miles from the Cumberland Gap, Boone and his party rested at Martin’s Station, a settlement near what is now Rose Hill, Virginia that had been founded by Joseph Martin in 1769. After a Native American attack, Martin and

his fellow settlers had abandoned the region, but they had returned in early 1775 to build a more permanent settlement. Just before reaching their intended settlement site on the Kentucky River in late March, Boone’s group was attacked by some of the Shawnee. They had not ceded their right to Kentucky’s land, like the Cherokee. Most of Boone’s men were able to escape, but a few were killed or injured. In April, the group finally arrived on the south side of the Kentucky River, in what is now Madison County, Kentucky.

his fellow settlers had abandoned the region, but they had returned in early 1775 to build a more permanent settlement. Just before reaching their intended settlement site on the Kentucky River in late March, Boone’s group was attacked by some of the Shawnee. They had not ceded their right to Kentucky’s land, like the Cherokee. Most of Boone’s men were able to escape, but a few were killed or injured. In April, the group finally arrived on the south side of the Kentucky River, in what is now Madison County, Kentucky.

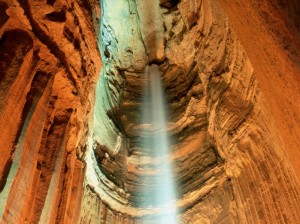

On a trip to Tennessee and the surrounding area in April of 2003, Bob and I had the opportunity to visit Lookout Mountain, which is located near Chattanooga, in southwestern Tennessee. The drive up was stunning, and everything we saw there from Ruby Falls, to the Incline Railway, and Rock City proved to hold amazing views as well. From the top of the mountain, you can see seven states…Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, and Alabama. The view across that area is spectacular. When we travel, we love to go sight seeing, so this area fit right into our idea of a great place to visit. looking back now, I’m sure that time constraints played a part in my missing out on some of the amazing historical value of the area I was visiting, and to me, that is really a shame, because so much took place there, and I didn’t even know it.

On a trip to Tennessee and the surrounding area in April of 2003, Bob and I had the opportunity to visit Lookout Mountain, which is located near Chattanooga, in southwestern Tennessee. The drive up was stunning, and everything we saw there from Ruby Falls, to the Incline Railway, and Rock City proved to hold amazing views as well. From the top of the mountain, you can see seven states…Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, and Alabama. The view across that area is spectacular. When we travel, we love to go sight seeing, so this area fit right into our idea of a great place to visit. looking back now, I’m sure that time constraints played a part in my missing out on some of the amazing historical value of the area I was visiting, and to me, that is really a shame, because so much took place there, and I didn’t even know it.

I suppose I should have known the history of the area, but apparently I wasn’t as up on my Civil War and Indian history as I am now. I really wish I had known or had at least taken more time reading the many signs in the area, because I could have figured out what a great area we were in. During the Nickajack Expedition which occurred in the 18th century, Lookout Mountain would become a last stand for the Chickamauga Cherokee, who were followers of Chief Dragging Canoe, who opposed the peace treaty between Native Americans and the American settlers. The peace treaty was signed in 1777. Most of the Chickamauga Cherokee agreed to the treaty, but a small band followed Chief Dragging Canoe, and they went to battle in the late summer through the fall of 1794. The final battle, and the point that Chief Dragging Canoe’s warriors would lose the fight took place on Lookout Mountain. The Indians were no match for the military might of the army, and after wounding only 3 of the militia, the villages of Nickajack Town and Running Water Town were destroyed, leaving seventy Cherokee dead.

The Civil War battle that made Lookout mountain famous took place on November 24, 1863 and was a part of the Chattanooga Campaign. Major General Joseph Hooker defeated the Confederate forces who were under the command of Major General Carter Stevenson. Lookout mountain has an excellent view of the Tennessee River, making it a perfect stronghold. It also held a perfect view of the Union supply lines, so if the Confederate army wanted to starve out the Union army, they needed Lookout Mountain, and if the Union army wanted to keep their supply lines clear, they needed Lookout Mountain. One of the hardest places to fight a battle is a mountain…at least for the side who is at the bottom of the mountain. They are far too visible to fight the battle easily. So, after calling for reinforcements, Major General Joseph Hooker went into battle. It was a must win situation. If they lost the Union soldiers would be starved into surrender.

Looking back now on our visit makes everything we saw seem much more interesting. In my memory files, I can pull out the different views of our visit to Lookout Mountain, and I can visualize the exact view the Confederate soldiers had, and knowing that there was virtually no place to hide, I can’t help but wonder how the Union soldiers managed to win that battle. I suppose that it was partly the numbers of soldiers, with

the Union having more than 1,000 more, but more importantly, I think it was the fact that they surrounded the Confederate soldiers, leaving them with too many sides to cover. Our trip to Lookout Mountain, Ruby Falls, and Rock City has taken on a whole new meaning for me. I wish I had known it then. I would have really enjoyed that stroll through history. The great thing is that my pictures, memories, and a little look at history can take me back to visit again.

the Union having more than 1,000 more, but more importantly, I think it was the fact that they surrounded the Confederate soldiers, leaving them with too many sides to cover. Our trip to Lookout Mountain, Ruby Falls, and Rock City has taken on a whole new meaning for me. I wish I had known it then. I would have really enjoyed that stroll through history. The great thing is that my pictures, memories, and a little look at history can take me back to visit again.