Japan

The Battle of Wake Island was a significant conflict in the Pacific theater of World War II, occurring on Wake Island. The attack began simultaneously with the assault on Pearl Harbor’s naval and air bases in Hawaii on the morning of December 8, 1941 (December 7th in Hawaii) and concluded on December 23rd with the American forces capitulating to the Empire of Japan. The battle took place on the atoll comprising Wake Island and its smaller islets, Peale and Wilkes, involving air, land, and sea forces of the Japanese Empire and the United States, with a notable presence of Marines from both nations. The Japanese forces were formidable, and the majority of the surviving Americans were transported from the island to POW camps by the Japanese. Ninety-seven were left behind to be used as forced labor. The Allies’ response involved intermittent bombing of the island, but no further land invasions occurred. This was in line with a broader Allied strategy to isolate certain Japanese-occupied islands in the South Pacific, effectively leaving them to wither in isolation.

The Battle of Wake Island was a significant conflict in the Pacific theater of World War II, occurring on Wake Island. The attack began simultaneously with the assault on Pearl Harbor’s naval and air bases in Hawaii on the morning of December 8, 1941 (December 7th in Hawaii) and concluded on December 23rd with the American forces capitulating to the Empire of Japan. The battle took place on the atoll comprising Wake Island and its smaller islets, Peale and Wilkes, involving air, land, and sea forces of the Japanese Empire and the United States, with a notable presence of Marines from both nations. The Japanese forces were formidable, and the majority of the surviving Americans were transported from the island to POW camps by the Japanese. Ninety-seven were left behind to be used as forced labor. The Allies’ response involved intermittent bombing of the island, but no further land invasions occurred. This was in line with a broader Allied strategy to isolate certain Japanese-occupied islands in the South Pacific, effectively leaving them to wither in isolation.

On October 5, 1943, American naval aircraft from the USS Yorktown attacked Wake Island. On October 7, 1943, Rear Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara, commander of the Japanese garrison on the island, orders the execution of a civilian accused of stealing, and 97 Americans POWs, claiming they were trying to make radio contact with US forces, and a civilian accused of stealing. Initially, the 97 POWs were detained to be used as forced labor. Anticipating an invasion, Sakaibara commanded their execution. They were led to the island’s northern end, blindfolded, and shot with a machine gun. One prisoner, whose name remains unknown, escaped and etched “98 US PW 5-10-43” into a large coral rock near the hastily dug mass grave. This American was later recaptured, and Sakaibara personally beheaded him with a katana. The etched message remains visible, marking a somber landmark on Wake Island to this day. The Wake Island Massacre was an outrage.

The Pacific war finally drew to a close starting in August 1945, and the Emperor of Japan announced the surrender to the Japanese people and the agreement was formally signed by September 2, 1945. On September 4, 1945, the remaining Japanese garrison surrendered to a detachment of United States Marines under the command of Brigadier General Lawson H. M. Sanderson, with the handover being officially conducted in a brief ceremony aboard the destroyer escort USS Levy. Earlier, the garrison received news that Imperial Japan’s defeat was imminent, so the mass grave was quickly exhumed, and the bones were moved to the US cemetery that had been established on Peacock Point after the invasion, with wooden crosses erected in preparation for the expected arrival of US forces. During the initial interrogations, the Japanese claimed that the remaining 98 Americans on the island were mostly killed by an American bombing raid, though some escaped and fought to the death after being cornered on the beach at the north end of Wake Island. Several Japanese officers in American custody committed suicide over the incident, leaving written statements that incriminated Sakaibara. Sakaibara and his subordinate, Lieutenant Commander Tachibana, were later sentenced

to death after conviction for this and other war crimes. Sakaibara was executed by hanging in Guam on June 19, 1947, while Tachibana’s sentence was commuted to life in prison. The remains of the murdered civilians were exhumed and reburied at Section G of the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, which is commonly known as Punchbowl Crater, on Honolulu.

to death after conviction for this and other war crimes. Sakaibara was executed by hanging in Guam on June 19, 1947, while Tachibana’s sentence was commuted to life in prison. The remains of the murdered civilians were exhumed and reburied at Section G of the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, which is commonly known as Punchbowl Crater, on Honolulu.

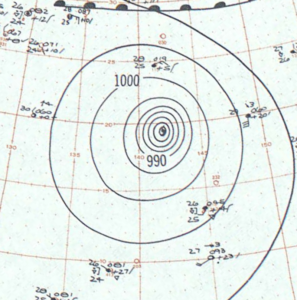

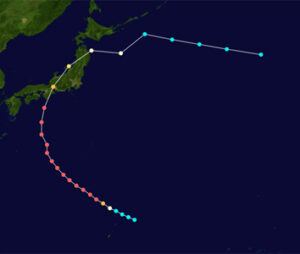

Typhoon Vera, also known as the Isewan Typhoon, was an extraordinarily powerful tropical cyclone that hit Japan in September 1959. It became the most intense and deadliest typhoon to ever make landfall in the country, and it remains the only one to have done so as a Category 5 equivalent storm. The typhoon caused unprecedented catastrophic damage, severely impacting the Japanese economy, which was in the midst of post-World War II recovery. Following Vera, Japan underwent significant reforms in disaster management and relief operations, establishing a new standard for handling future storms. The country is still well known for its disaster preparedness.

Typhoon Vera, also known as the Isewan Typhoon, was an extraordinarily powerful tropical cyclone that hit Japan in September 1959. It became the most intense and deadliest typhoon to ever make landfall in the country, and it remains the only one to have done so as a Category 5 equivalent storm. The typhoon caused unprecedented catastrophic damage, severely impacting the Japanese economy, which was in the midst of post-World War II recovery. Following Vera, Japan underwent significant reforms in disaster management and relief operations, establishing a new standard for handling future storms. The country is still well known for its disaster preparedness.

Typhoon Vera formed on September 20 between Guam and Chuuk State, initially moving westward before shifting to a northerly path and reaching tropical storm status the next day. The storm then took a turned westward, rapidly intensifying to peak intensity on September 23 with maximum sustained winds that made it Category 5 hurricane. Maintaining its strength, Vera veered northward and made landfall near Shionomisaki on Honshu on September 26. Influenced by atmospheric winds, the typhoon briefly entered the Sea of Japan, then recurved eastward, making a second landfall on Honshu. Crossing over land significantly weakened Vera, and

upon reentering the North Pacific Ocean that same day, it became an extratropical cyclone on September 27, with its remnants lasting two more days.

upon reentering the North Pacific Ocean that same day, it became an extratropical cyclone on September 27, with its remnants lasting two more days.

Although Vera’s path into Japan was accurately predicted, the limited telecommunications coverage, combined with the Japanese media’s lack of urgency and the storm’s severity, significantly hindered evacuation and disaster prevention efforts. The flooding from the storm’s peripheral rainbands started affecting river basins before the typhoon made landfall. As it hit Honshu, Vera unleashed a powerful storm surge, destroying many flood defenses, flooding coastal areas, and causing ships to sink. Vera resulted in damages totaling $600 million US dollars, which was equivalent to $6.27 billion US dollars in 2023. The death toll from Vera is uncertain, but current figures suggest the typhoon caused over 5,000 deaths, ranking it among the most lethal typhoons in Japan’s history. Additionally, it injured nearly 39,000 individuals and also displaced around 1.6 million people.

Immediately after Typhoon Vera, the Japanese and American governments launched relief operations. The typhoon’s flooding led to localized outbreaks of diseases such as dysentery and tetanus. These epidemics, along

with obstructive debris, hindered the relief process. In response to the extensive damage and casualties caused by Vera, the National Diet, which is the national legislature of Japan, enacted laws to better support the impacted areas and reduce the impact of future disasters. This led to the creation of the Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act in 1961, which laid down guidelines for disaster response in Japan, including forming the Central Disaster Prevention Council.

with obstructive debris, hindered the relief process. In response to the extensive damage and casualties caused by Vera, the National Diet, which is the national legislature of Japan, enacted laws to better support the impacted areas and reduce the impact of future disasters. This led to the creation of the Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act in 1961, which laid down guidelines for disaster response in Japan, including forming the Central Disaster Prevention Council.

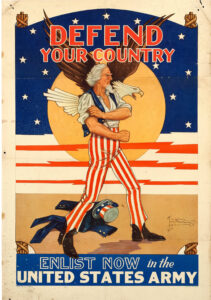

Understandably, the size of the various armies has grown along with human civilization. It is estimated that nearly 28 million armed forces personnel stand at the ready globally in this present day, according to the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of course, peacetime armies would likely be smaller than wartime armies. World War II saw the most soldiers ever to be amassed…with about 70 million soldiers. Approximately 42 million of those soldiers were from the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Japan. These nations armies and related services were four of the largest ever rallied to the battlefield. The largest three were the United States (12,209,000 troops in August 1945), the German Reich (12,070,000 troops in June 1944), and the Soviet Union (11,000,000 troops in June 1943). Those numbers are staggering to think about.

Understandably, the size of the various armies has grown along with human civilization. It is estimated that nearly 28 million armed forces personnel stand at the ready globally in this present day, according to the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of course, peacetime armies would likely be smaller than wartime armies. World War II saw the most soldiers ever to be amassed…with about 70 million soldiers. Approximately 42 million of those soldiers were from the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Japan. These nations armies and related services were four of the largest ever rallied to the battlefield. The largest three were the United States (12,209,000 troops in August 1945), the German Reich (12,070,000 troops in June 1944), and the Soviet Union (11,000,000 troops in June 1943). Those numbers are staggering to think about.

As is expected in a world war, many soldiers are needed. So, the World War II army of the US became the biggest army in history. Citizens of the United States are notorious for patriotism, when we have been attacked. It is like waking a sleeping giant, and we will retaliate with a vengeance. Due in part to that surge of American patriotism and also because of conscription (the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service,

mainly a military service), the US Army numbered 12,209,000 soldiers by the end of the war in 1945. It is little surprise that the Japanese found themselves surrendering to the United States on this day, September 2, 1945. of course, the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left little doubt that the Americans not only had the atomic bomb, but we would us it. Basically, their choices were to stay in the fight and die or surrender. They chose the latter, and the rest is history.

mainly a military service), the US Army numbered 12,209,000 soldiers by the end of the war in 1945. It is little surprise that the Japanese found themselves surrendering to the United States on this day, September 2, 1945. of course, the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left little doubt that the Americans not only had the atomic bomb, but we would us it. Basically, their choices were to stay in the fight and die or surrender. They chose the latter, and the rest is history.

In order to determine which of the armies were the largest in history, 24/7 Wall Street reviewed a list of military superpowers from Business Insider. These armies were ranked based on the total number of troops that were serving a country or empire at the point when the army was at its largest. Without doubt, the United States was, and remains to this day, the nation with the largest army in history. Over the years, the armed forces of the United States have been larger and smaller, depending on the need at the time, the administration

in charge, and since the draft was discontinued, the number of people who chose to join up to serve their country and to qualify for the GI Bill so that they can get free college. No matter how they got in the service, or how long they stayed, I am very proud of all of our soldiers over the many years of this nation…and I thank them for their service. On this day, the largest army in history accepted the surrender of the Japanese, who had once had the nerve to attack us on our own soil. That was their biggest mistake ever.

in charge, and since the draft was discontinued, the number of people who chose to join up to serve their country and to qualify for the GI Bill so that they can get free college. No matter how they got in the service, or how long they stayed, I am very proud of all of our soldiers over the many years of this nation…and I thank them for their service. On this day, the largest army in history accepted the surrender of the Japanese, who had once had the nerve to attack us on our own soil. That was their biggest mistake ever.

It was a typical lunch hour in Japan’s capital city of Tokyo, and the neighboring “City of Silk” Yokohama that September 1, 1923. People were out and about doing their normal lunchtime things, eating and running errands before going back to work. Suddenly the days routine was shattered when a massive, 7.9-magnitude earthquake struck just before noon. The shaking lasted just 14 seconds, but that was all it took to bring down nearly every building in Yokohama, which is just south of Tokyo. The shaking also caused more than half of Tokyo’s brick buildings, most of Yokohama’s buildings, and hundreds of thousands of homes to collapse, killing tens of thousands of people instantly.

It was a typical lunch hour in Japan’s capital city of Tokyo, and the neighboring “City of Silk” Yokohama that September 1, 1923. People were out and about doing their normal lunchtime things, eating and running errands before going back to work. Suddenly the days routine was shattered when a massive, 7.9-magnitude earthquake struck just before noon. The shaking lasted just 14 seconds, but that was all it took to bring down nearly every building in Yokohama, which is just south of Tokyo. The shaking also caused more than half of Tokyo’s brick buildings, most of Yokohama’s buildings, and hundreds of thousands of homes to collapse, killing tens of thousands of people instantly.

Known as the Great Kanto Earthquake, but also called the Tokyo-Yokohama Earthquake, of 1923, it caused an estimated death toll of more than 140,000 and left some 1.5 million people homeless, according to reported numbers. Following the earthquake came another disaster in the form of fires that burned many buildings. Most likely, this was because in 1923, people cooked over an open flame, and the quake struck while people were preparing lunch. To further complicate matters, the area was hit by high winds, caused by a typhoon that passed off the coast of the Noto Peninsula in northern Japan, spread the flames and created horrifying firestorms. Because the quake had snapped water mains, the fires could not be extinguished until September 3rd. By that time, about 45 percent of Tokyo had burned. Some researchers believed that the typhoon may have triggered the earthquake, because the forced atmospheric pressure pressed on a stressed and delicate fault line of three major tectonic plates that meet under Tokyo. I wasn’t aware that this was possible, but  apparently it is. The quake also triggered a tsunami that swelled to 39.5 feet at Atami on the Sagami Gulf, where 60 people were killed and 155 homes destroyed.

apparently it is. The quake also triggered a tsunami that swelled to 39.5 feet at Atami on the Sagami Gulf, where 60 people were killed and 155 homes destroyed.

The damage from all this in Toyko was so severe that some government leaders argued for moving the Japanese capital to a new city. Educator, Miura Tosaku toured the destruction of Tokyo in the fall of 1923, concluded that the earthquake was an apocalyptic revelation. He wrote: “Disasters take away the falsehood and ostentation of human life and conspicuously expose the strengths and weaknesses of human society.” Tenrikyo relief worker Haruno Ki’ichi said, “The destruction and devastation in the earthquake aftermath surpassed imagination.”

Yokohama’s Victorian-era Grand Hotel, that had hosted famous people including US President William Howard Taft and English author Rudyard Kipling, completely collapsed. Hundreds of hotel employees and guests were crushed. Henry W Kinney, a Tokyo-based editor of the Trans-Pacific publication, observed the devastation in Yokohama hours after the earthquake hit. He wrote, “Yokohama, the city of almost half a million souls, had become a vast plain of fire, of red, devouring sheets of flame which played and flickered. Here and there a remnant of a building, a few shattered walls, stood up like rocks above the expanse of flame, unrecognizable … It was as if the very Earth were now burning. It presented exactly the aspect of a gigantic Christmas pudding over which the spirits were blazing, devouring nothing. For the city was gone.”

Since 1960, the Japanese people recognize the September 1 anniversary of the earthquake as Disaster Prevention Day. It’s a noble idea, but I’m not sure how these disasters could be prevented, other than the now common practice of earthquake proofing buildings to prevent so much loss. Nevertheless, Japan has suffered through several more devastating earthquakes. More than seven decades after the 1923 disaster, an earthquake struck Kobe on January 17, 1995. This Kobe Earthquake caused an estimated 6,400 deaths, widespread fires, and a landslide in Nishinomiya. Then, on March 11, 2011, a 9.0-magnitude temblor struck off th

e coast of Japan’s city of Sendai. This Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami caused a series of catastrophic tsunamis in Japan, and more than 18,000 estimated deaths. I suppose that to say the very least, the loss of life in these more recent quakes, was far less than in the original event that founded Disaster Prevent Day.

e coast of Japan’s city of Sendai. This Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami caused a series of catastrophic tsunamis in Japan, and more than 18,000 estimated deaths. I suppose that to say the very least, the loss of life in these more recent quakes, was far less than in the original event that founded Disaster Prevent Day.

The mission began on July 29, 1953. The B-50 Superfortress piloted by Captain Stanley K O’Kelley had a total of seventeen crewmembers aboard. Its mission was a reconnaissance flight over North Korea. It took off from Honshu, Japan. As the plane headed out across the Sea of Japan, on its way to North Korea, it was intercepted and shot down by a pair of MiG-17s (or possibly MiG-15s) piloted by two Soviet pilots (Yablonskiy and Rybakov), south of Askold Island near Vladivostok. They immediately opened fire, and quickly shot down B-50 Superfortress number 15830. The plane crashed into the Sea of Japan. Amazingly, there was one survivor, and unfortunately, the rest of the crew died in the crash.

The mission began on July 29, 1953. The B-50 Superfortress piloted by Captain Stanley K O’Kelley had a total of seventeen crewmembers aboard. Its mission was a reconnaissance flight over North Korea. It took off from Honshu, Japan. As the plane headed out across the Sea of Japan, on its way to North Korea, it was intercepted and shot down by a pair of MiG-17s (or possibly MiG-15s) piloted by two Soviet pilots (Yablonskiy and Rybakov), south of Askold Island near Vladivostok. They immediately opened fire, and quickly shot down B-50 Superfortress number 15830. The plane crashed into the Sea of Japan. Amazingly, there was one survivor, and unfortunately, the rest of the crew died in the crash.

Captain John Ernst Roche was that survivor, and when it became known that the bomber had failed to return, a search was started. It was thought that some of the other crew might have survived, and life rafts were dropped, but no one else was saved in the end. It was thought that at least four of them (and possibly more) were seen sitting in the raft. Also seen were nine Soviet PT-type boats in the area and at least six of them were heading to the location where debris from the aircraft was later discovered. A Soviet trawler was also spotted in the approximate area. Knowing that, I suppose any of the other survivors were killed. The United States conducted a thorough search of the area by air and sea and was assisted by an Australian ship near the crash site. The search was halted due to dense fog and approaching darkness, and the search was resumed on the morning of July 30, 1953. Captain John Roche, co-pilot of the plane, was wounded but survived the crash by holding onto pieces of the wreckage. He was finally picked up by the Navy ship USS Picking in the early morning hours of July 30, 1953, after floating in the Sea of Japan for about 22 hours. Unfortunately, no other survivors were found. The bodies of Captain Stanley O’Kelley and Master Sergeant Francis Brown were later recovered along the coast of Japan. The remaining 14 members of the crew, which included Robert Stalnaker, were never found. The crew members were First Lieutenant Frank E Beyer (MIA), Master Sergeant Francis L Brown (body recovered), First Lieutenant Edmund J Czyc (MIA), Staff Sergeant Donald W Gabree, (MIA), Airman First Class Roland E Goulet (status unknown), Staff Sergeant Donald G Hill (MIA), First Lieutenant James G Keith (KIA), Captain Stanley K O’Kelley (body recovered), Airman Second Class Earl W Radelin Jr (MIA), Captain John E Roche (rescued the next day on July 30, 1953), Airman Second Class, Charles J Russell (MIA), First Lieutenant Warren J Sanderson (MIA), First Lieutenant Robert E Stalnaker (MIA), Major Francisco J Tejeda (MIA), Captain John C Ward (MIA), First Lieutenant Lloyd C Wiggins (MIA), and Airman Second Class James E Woods (MIA).

The B50 Superfortress number 47-145 (Manufacture Number 15830) was built by Boeing. It was delivered to the US Air Force (USAF) as B-50B-50-BO Superfortress serial number 47-145. So that the bomber could be

used as a spy plane, it was modified as RB-50G ELINT with additional radar and B-50D type nose, sometimes also referred to as RB-50D. It was then assigned as a spy plane, to the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron (91st SRS) based at Yokato AFB. It was working in that capacity when it was shot down.

used as a spy plane, it was modified as RB-50G ELINT with additional radar and B-50D type nose, sometimes also referred to as RB-50D. It was then assigned as a spy plane, to the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron (91st SRS) based at Yokato AFB. It was working in that capacity when it was shot down.

After World War I ended, war weary Americans decided that we needed to isolate ourselves from the rest of the world to a degree, in order to protect ourselves. Of course, that didn’t stop people from other countries from wanting to immigrate to the United States. The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act reflected that desire. Americans wanted to push back and distance ourselves from Europe amid growing fears of the spread of communist ideas. The new law seemed the best way to accomplish that. Unfortunately, the law also reflected the pervasiveness of racial discrimination in American society at the time. As more and more largely unskilled and uneducated immigrants tried to come into America, many Americans saw the enormous influx of immigrants during the early 1900s as causing unfair competition for jobs and land.

After World War I ended, war weary Americans decided that we needed to isolate ourselves from the rest of the world to a degree, in order to protect ourselves. Of course, that didn’t stop people from other countries from wanting to immigrate to the United States. The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act reflected that desire. Americans wanted to push back and distance ourselves from Europe amid growing fears of the spread of communist ideas. The new law seemed the best way to accomplish that. Unfortunately, the law also reflected the pervasiveness of racial discrimination in American society at the time. As more and more largely unskilled and uneducated immigrants tried to come into America, many Americans saw the enormous influx of immigrants during the early 1900s as causing unfair competition for jobs and land.

Under the new law, immigration was to remain open to those with a “college education and/or special skills, but entry was denied disproportionately to Eastern and Southern Europeans and Japanese.” At the same time, the legislation allowed for more immigration from Northern European nations such as Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavian countries. The law also set a quota that limited immigration to two percent of any given nation’s residents already in the US as of 1890, a provision designed to maintain America’s largely Northern European racial composition. In 1927, the “two percent rule” was eliminated and a cap of 150,000 total immigrants annually was established. While this was more fair all around, it particularly angered Japan. In 1907, Japan and US President Theodore Roosevelt had created a “Gentlemen’s Agreement,” which included more liberal immigration quotas for Japan. Of course, that was unfair to other nations looking to send immigrants to the United States. Strong US agricultural and labor interests, particularly from California, had already pushed through a form of exclusionary laws against Japanese immigrants by 1924, so they favored the more restrictive legislation signed by Coolidge.

Of course, the Japanese government felt that the American law as an insult and protested by declaring May 26  a “National Day of Humiliation” in Japan. With that, Japan experienced a wave of anti-American sentiment, inspiring a Japanese citizen to commit suicide outside the American embassy in Tokyo in protest. That created more anti-American sentiment, but in the end, it made no difference. On May 26, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924 into law. It was the most stringent and possibly the most controversial US immigration policy in the nation’s history up to that time. Despite becoming known for such isolationist legislation, Coolidge also established the Statue of Liberty as a national monument in 1924.

a “National Day of Humiliation” in Japan. With that, Japan experienced a wave of anti-American sentiment, inspiring a Japanese citizen to commit suicide outside the American embassy in Tokyo in protest. That created more anti-American sentiment, but in the end, it made no difference. On May 26, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924 into law. It was the most stringent and possibly the most controversial US immigration policy in the nation’s history up to that time. Despite becoming known for such isolationist legislation, Coolidge also established the Statue of Liberty as a national monument in 1924.

Serious accidents happen, and they are almost always due to negligence on the side of one party or the other, but when two automobiles, planes, ships, or trains hit each other head-on, someone was seriously in the wrong place and going the wrong way. On May 14, 1991, two diesel trains carrying commuters crashed head-on, near Shigaraki, Japan, killing 42 people and injuring over 600 others. This was the worst rail disaster in Japan since a November 1963 Yokohama crash, which killed 160 people.

Serious accidents happen, and they are almost always due to negligence on the side of one party or the other, but when two automobiles, planes, ships, or trains hit each other head-on, someone was seriously in the wrong place and going the wrong way. On May 14, 1991, two diesel trains carrying commuters crashed head-on, near Shigaraki, Japan, killing 42 people and injuring over 600 others. This was the worst rail disaster in Japan since a November 1963 Yokohama crash, which killed 160 people.

Shigaraki, a town near Kyoto, is famous for its ceramics. On that May 14th, the World Ceramics Festival was being held in the town. That put many more people in town than normal. It also filled the passenger trains with people on their way to the event. At just after 10am, passengers filled a train in Kikukawa, which was to run along a 9.1-mile single-track rail line away from Shigaraki. When the train was loaded, the However, workers on the Shigaraki Kogen Railways (SKR) line prepared to depart, but they could not get a green signal indicating that the track was clear so they could  depart from the station. The system showed that a train was approaching. The workers believed the signal was malfunctioning, and so they overrode the system and sent the train out, 11 minutes late.

depart from the station. The system showed that a train was approaching. The workers believed the signal was malfunctioning, and so they overrode the system and sent the train out, 11 minutes late.

Sadly, they were to find out too late that the system had been correct and a JR West commuter train carrying passengers toward Shigaraki for the festival was speeding toward them. The only mechanical failure that day was when a faulty-departure detector failed to work correctly, sending the JR West commuter train out on a collision course with the SKR train. The resulting crash derailed both trains and cost 42 people their lives. Very seldom does the fault in an accident lie with just one person. A subsequent investigation faulted the SKR workers for allowing the train to depart without a green signal, an action found to be dangerous and illegal. A signal engineer was also blamed for the defective wiring that led to the failure of the faulty-departure detector that should have prevented the collision. A 1999 civil trial resulted in a 500-million-yen (3,196,500 US dollars) award to the victims against SKR and JR West jointly. JR West pledged

safety improvements (after the Shigaraki accident), but it again had an accident in Amagasaki. The Amagasaki rail crash was a fatal railway accident that occurred on April 25, 2005, at 9:19am local time. Of the roughly 700 passengers (initial estimate was 580 passengers) on board at the time of the crash, 106 passengers, in addition to the driver, were killed and 562 others injured. Each year, since the disaster, the victims of the Shigaraki Head-On collision are remembered in a ceremony in Shigaraki.

safety improvements (after the Shigaraki accident), but it again had an accident in Amagasaki. The Amagasaki rail crash was a fatal railway accident that occurred on April 25, 2005, at 9:19am local time. Of the roughly 700 passengers (initial estimate was 580 passengers) on board at the time of the crash, 106 passengers, in addition to the driver, were killed and 562 others injured. Each year, since the disaster, the victims of the Shigaraki Head-On collision are remembered in a ceremony in Shigaraki.

On December 10, 1968, the 300-million-yen robbery, also known as the 300-million-yen affair or incident, took place in Tokyo, Japan, when a man posing as a police officer on a motorcycle performed a “traffic stop” of some bank employees transferring money and stole about 294 million yen. This as half-century old unsolved heist remains the single largest heist in Japanese history. On that fateful day, four Kokubunji branch employees of the Nihon Shintaku Ginko (Nippon Trust Bank) were transporting 294,307,500 yen (about US$817,520 at 1968 exchange rates) in the trunk of a Nissan Cedric company car. It seems like a rather odd and very unsecure way to transfer such a large sum of money, but apparently, they saw no danger…a mistake they would most certainly regret. The money, contained in metal boxes was to be for bonuses for the employees of Toshiba’s Fuchu factory.

On December 10, 1968, the 300-million-yen robbery, also known as the 300-million-yen affair or incident, took place in Tokyo, Japan, when a man posing as a police officer on a motorcycle performed a “traffic stop” of some bank employees transferring money and stole about 294 million yen. This as half-century old unsolved heist remains the single largest heist in Japanese history. On that fateful day, four Kokubunji branch employees of the Nihon Shintaku Ginko (Nippon Trust Bank) were transporting 294,307,500 yen (about US$817,520 at 1968 exchange rates) in the trunk of a Nissan Cedric company car. It seems like a rather odd and very unsecure way to transfer such a large sum of money, but apparently, they saw no danger…a mistake they would most certainly regret. The money, contained in metal boxes was to be for bonuses for the employees of Toshiba’s Fuchu factory.

As the car proceeded along its route to the home of the bank manager for delivery to the factory, a young man in the uniform of a motorcycle police officer blocked the path of the car. Like most of us would do, when faced with an authority figure telling us to stop, the men in the car obeyed the “officer” and a mere 200 meters from its destination, on a street next to Tokyo Fuchu Prison they stopped. The impersonator informed the bank employees that their bank branch manager’s house had been destroyed by an explosion, and a warning had been received that a bomb had also been planted in the car. The four employees quickly exited the vehicle, while the police officer crawled under the car. Moments later, the “officer” he rolled out, shouting that the car was about to explode and telling the employees to run. Smoke and flames appeared underneath the car. The employees quickly retreated, and “police officer” got into it and drove away. I’m sure it took several moments for the employees to figure out that there was no bomb, and the “officer” wasn’t a selfless hero trying to get the car away from any innocent bystanders…especially when there was no explosion, and the “officer” didn’t come back. They were now faced with a new and unpleasant dilemma…telling their boss they had been duped.

The “police officer” had worked out his story well, telling the bank employees he knew about the bomb because  threatening letters had been sent to the bank manager beforehand. He was also prepared with a warning flare to create the smoke and flames he had ignited while under the car. At some point, the thief abandoned the bank’s car and transferred the metal boxes to another car, which he had stolen beforehand. Then, he also abandoned that car and transferred the boxes into to another previously stolen vehicle. He had laid out his plan very well, but there were, nevertheless, 120 pieces of evidence left at the scene of the crime, including the “police” motorcycle, which had been painted white. Unfortunately, the evidence was mostly common everyday items. It is believed that he scattered them around on purpose to confuse the police investigation…a planned which seems to have worked quite well too.

threatening letters had been sent to the bank manager beforehand. He was also prepared with a warning flare to create the smoke and flames he had ignited while under the car. At some point, the thief abandoned the bank’s car and transferred the metal boxes to another car, which he had stolen beforehand. Then, he also abandoned that car and transferred the boxes into to another previously stolen vehicle. He had laid out his plan very well, but there were, nevertheless, 120 pieces of evidence left at the scene of the crime, including the “police” motorcycle, which had been painted white. Unfortunately, the evidence was mostly common everyday items. It is believed that he scattered them around on purpose to confuse the police investigation…a planned which seems to have worked quite well too.

One suspect was the 19-year-old son of a police officer. That young man died of potassium cyanide poisoning on December 15, 1968. He had no alibi, which may not have meant anything, since the money was not found at the time of his death. His death was deemed a suicide, and he was considered not guilty, according to official record. There was simply no evidence to tie him to the crime. Another, arrest made on December 12, 1969, of a 26-year-old man, who was suspected by the Mainichi Shimbun, proved to be a dead end too, when his alibi checked out. The arrest was initially made on an unrelated charge, but on the day of the robbery, he was taking a proctored examination. The only resulting charge from that arrest was that of “abuse of power” as the arrest was made based on false pretenses.

The police launched a massive investigation, posting 780,000 composite pictures throughout Japan. Amazingly, the list of suspects (or as it really must have been, persons of interest) included 110,000 names. These had to have been people the police thought might possibly be able to carry off such a heist, because it would really be impossible to have that many real suspects. Approximately 170,000 policemen participated in the investigation, which was the largest investigation in Japanese history…or so the story goes. They gathered and examined fingerprints from the scene and comparison of them to those on file. In the end, six million fingerprints on file were compared individually, however not a single match was found.

On November 15, 1975, just before the statute of limitations for that crime was over, a friend of the 19-year-old suspect was arrested on an unrelated charge. He had a large amount of money and was suspected of the  robbery. He was 18 years old when the robbery occurred. The police asked him for an explanation for the large amount of money, but he refused to speak, and they were not able to prove that his money had come from the robbery. In December 1975, after a seven-year investigation, police announced that the statute of limitations on the crime had passed, and that the investigation was at an end. In a further slap to justice, as of 1988, the thief has also been relieved of any civil liabilities, which means that he can tell his story without fear of legal repercussions. Still, no one has ever stepped forward to “tell said story” either, which tends to further exasperate the authorities, because it is the unsolved crimes that torment a police officer the most.

robbery. He was 18 years old when the robbery occurred. The police asked him for an explanation for the large amount of money, but he refused to speak, and they were not able to prove that his money had come from the robbery. In December 1975, after a seven-year investigation, police announced that the statute of limitations on the crime had passed, and that the investigation was at an end. In a further slap to justice, as of 1988, the thief has also been relieved of any civil liabilities, which means that he can tell his story without fear of legal repercussions. Still, no one has ever stepped forward to “tell said story” either, which tends to further exasperate the authorities, because it is the unsolved crimes that torment a police officer the most.

Japan entered World War I as a member of the Allies on August 23, 1914. Assisting the Allies with the war effort was not their reason for doing so, however. Once in, Japan seized the opportunity of Imperial Germany’s distraction with the European War to expand its sphere of influence in China and the Pacific. Because Japan already had a military alliance with Britain, there was minimal fighting as they pushed through to make their territorial gains. Japan was not pressured to enter the war. The Allies had things well in hand, so their motive was obvious. As they swept through, they quickly acquired Germany’s scattered small holdings in the Pacific and on the coast of China. While those holdings were relatively easy to overtake, not all of Germany’s holdings were so easy.

Japan entered World War I as a member of the Allies on August 23, 1914. Assisting the Allies with the war effort was not their reason for doing so, however. Once in, Japan seized the opportunity of Imperial Germany’s distraction with the European War to expand its sphere of influence in China and the Pacific. Because Japan already had a military alliance with Britain, there was minimal fighting as they pushed through to make their territorial gains. Japan was not pressured to enter the war. The Allies had things well in hand, so their motive was obvious. As they swept through, they quickly acquired Germany’s scattered small holdings in the Pacific and on the coast of China. While those holdings were relatively easy to overtake, not all of Germany’s holdings were so easy.

In fact, the other Allies quickly started to realize that Japan’s motives weren’t exactly in everyone’s best interests, and they began to push back hard against Japan’s efforts to dominate China through the Twenty-One Demands of 1915. Japan’s occupation of Siberia against the Bolsheviks failed, as its wartime diplomacy and limited military action produced few results. Then, by the time of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Japan was largely frustrated in its ambitions. Nevertheless, Japan had snapped up Germany’s Asian colonies with ease, and even the African colony of Togoland (now Togo and parts of Ghana) fell in less than three weeks. The first real sign of resistance was when German Kamerun (Cameroon) was invaded and lightly contested until 1916. Still, it fell in the end. It seemed that Japan was undefeatable.

Nevertheless, with all the victories, the German colonies in East Africa led by the formidable and undefeated Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck proved to be the exception to the rule. The situation facing von Lettow-Vorbeck and his colonial forces was formidable. Still, von Lettow-Vorbeck knew how to fight, and he refused to back down. When the Japanese came up against von Lettow-Vorbeck, they found themselves heavily outnumbered, and they found themselves with no prospect of reinforcements or much in the way of material support arriving anytime soon.

The fact was that von Lettow-Vorbeck was seeking to tie up British military resources in Africa to relieve some pressure on the European theater. He drew upon his many years of service in Africa to wage a highly effective guerilla war against a much larger enemy. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was probably one of the greatest guerilla warfare strategists of all time…maybe the greatest. Von Lettow-Vorbeck even gained the loyalty of his African soldiers. In those days, it was highly unusual for a commanding officer or any white soldier for that matter, to show any level of respect to the African soldiers. Von Lettow-Vorbeck did, by appointing Black officers and speaking Swahili. The German troops had learned to live off the land and make the most of very little supplies, due to hard lessons drawn from years of colonial warfare in Africa. Those years were filled with atrocities, but they had persevered.

This one small German colonial army tied up the British forces for the duration of the conflict. The British had been plundering food  supplies that devastated the local population. Finally, the German army surrendered on November 25, 1918, in Zambia, two weeks after the November 11, 1918 armistice ended hostilities. Of course, Hitler knew a great officer when he saw one, and so after the war, Hitler immediately offered von Lettow-Vorbek a prestigious position in the Third Reich. In what most would consider a complete shock, von Lettow-Vorbeck bluntly refused the offer, using some very “colorful” language, which shall not be repeated here. It was a courageous, but not very wise move, given the circumstances. Nevertheless, his boldness, as well as his loyalty to the German people, paid off. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was simply too popular with the German people to be eliminated by the regime. He lived to be 94.

supplies that devastated the local population. Finally, the German army surrendered on November 25, 1918, in Zambia, two weeks after the November 11, 1918 armistice ended hostilities. Of course, Hitler knew a great officer when he saw one, and so after the war, Hitler immediately offered von Lettow-Vorbek a prestigious position in the Third Reich. In what most would consider a complete shock, von Lettow-Vorbeck bluntly refused the offer, using some very “colorful” language, which shall not be repeated here. It was a courageous, but not very wise move, given the circumstances. Nevertheless, his boldness, as well as his loyalty to the German people, paid off. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was simply too popular with the German people to be eliminated by the regime. He lived to be 94.

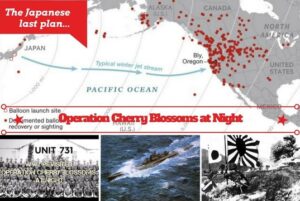

In 1945, a Japanese scientist named Shiro Ishii devised a plan of attack on civilians in the United States called Operation PX, also known as Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night. The plan was intended to wage biological warfare upon civilian population centers in the continental United States during the final months of World War II. The plan was devious, and heinous. Ishii planned to spread plague-infected fleas over Southern California using airplanes. The original operation was abandoned shortly after its planning on March 26, 1945. Then, with modifications, it was finalized and placed back of the table to be carried out. The plan was to be carried out on September 22nd, 1945. Unfortunately for Japan, their formal surrender date was August 15th, 1945, and the war was over.

In 1945, a Japanese scientist named Shiro Ishii devised a plan of attack on civilians in the United States called Operation PX, also known as Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night. The plan was intended to wage biological warfare upon civilian population centers in the continental United States during the final months of World War II. The plan was devious, and heinous. Ishii planned to spread plague-infected fleas over Southern California using airplanes. The original operation was abandoned shortly after its planning on March 26, 1945. Then, with modifications, it was finalized and placed back of the table to be carried out. The plan was to be carried out on September 22nd, 1945. Unfortunately for Japan, their formal surrender date was August 15th, 1945, and the war was over.

Originally, the Japanese Naval General Staff, led by Vice-Admiral Jisaburi Ozawa proposed Operation PX in December 1944. The code name for the operation came from the Japanese use of the code name PX for Pestis bacillus-infected fleas. The navy partnered with Lieutenant-General Shiro Ishii of Unit 731. Ishii possessed extensive experience on weaponizing pathogenic bacteria and human vulnerability to biological and chemical  warfare, and he was an extremely evil man, willing to use his knowledge for the murders of millions of people, especially if he thought it would bring him more power.

warfare, and he was an extremely evil man, willing to use his knowledge for the murders of millions of people, especially if he thought it would bring him more power.

In Ishii’s plan, they would use Seiran aircraft launched by submarine aircraft carriers upon the West Coast of the United States, targeting specifically, the cities of San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. The attack was to be utilizing weaponized bubonic plague, cholera, typhus, dengue fever, and other pathogens in a biological terror attack upon the population of the United States. The original plan was to have the submarine crews infect themselves and run ashore in a suicide mission. When the operation was shelved in March of 1945, it was because Umezu could see the future ramifications, and conveyed as much, when he said, “If bacteriological warfare is conducted, it will grow from the dimension of war between Japan and America to an endless battle of humanity against bacteria. Japan will earn the derision of the world.”

The idea of suicide attacks was tabled, due to opposition from Yoshijiro Umezu and Torashiro Kawabe, who did not want Ishii to die in a suicide attack and asked him to instead “wait for [the] next opportunity calmly”. It was then that Ishii devised a final plan using of the biological weapons and fleas…an attack that never took place either. The world never knew of the planned attack until long after the war, when Operation PX was first

discussed in an interview by former captain Eno Yoshio, who was heavily involved with planning for the attack. He first spoke of it in an interview with Sankei on August 14, 1977. According to Yoshio, “This is the first time I have said anything about Operation PX, because it involved the rules of war and international law. The plan was not put into actual operation, but I felt that just the fact that it was formulated would cause international misunderstanding. I never even leaked anything to the staff of the war history archives at the Japanese Defense Agency, and I don’t feel comfortable talking about it even now. But at the time, Japan was losing badly, and any means to win would have been all right.” That interview goes to show how horrible some regimes can be.

discussed in an interview by former captain Eno Yoshio, who was heavily involved with planning for the attack. He first spoke of it in an interview with Sankei on August 14, 1977. According to Yoshio, “This is the first time I have said anything about Operation PX, because it involved the rules of war and international law. The plan was not put into actual operation, but I felt that just the fact that it was formulated would cause international misunderstanding. I never even leaked anything to the staff of the war history archives at the Japanese Defense Agency, and I don’t feel comfortable talking about it even now. But at the time, Japan was losing badly, and any means to win would have been all right.” That interview goes to show how horrible some regimes can be.