great potato famine

When my Aunt Sandy Pattan and I go to lunch, she will usually forego vegetables for a double portion of mashed potatoes. Her request will usually accompany her asking me if I know that she is Irish, and so the love of potatoes. Of course, I know that she is Irish, because she is my aunt, and I know about my own Irish ties through her side of the family. Nevertheless, I can’t say that I connected the Irish part with potatoes. So, I decided to do a little research to find our why “the Irish like potatoes” as my aunt says. In my research, I found probably the last thing I expected.

When my Aunt Sandy Pattan and I go to lunch, she will usually forego vegetables for a double portion of mashed potatoes. Her request will usually accompany her asking me if I know that she is Irish, and so the love of potatoes. Of course, I know that she is Irish, because she is my aunt, and I know about my own Irish ties through her side of the family. Nevertheless, I can’t say that I connected the Irish part with potatoes. So, I decided to do a little research to find our why “the Irish like potatoes” as my aunt says. In my research, I found probably the last thing I expected.

In the annals of Irish history, the potato transcends its role as a staple food; it embodies both prosperity and hardship. It was instrumental in supporting the population during times of expansion, yet it also played a pivotal role in one of Ireland’s most catastrophic episodes: the Great Famine. The story of the potato in Ireland  is a tale of how a single crop can influence the fate of a nation, weaving itself into the very fabric of the Irish cultural identity.

is a tale of how a single crop can influence the fate of a nation, weaving itself into the very fabric of the Irish cultural identity.

Few events in Irish history are as dark and devastating as the Great Hunger, also known as the Potato Famine. At that time, Ireland was a colony of Great Britain, which relied heavily on the country for potato production. However, in 1845, a devastating disease destroyed 75% of the potato crop, persisting for over five years. The local Irish population suffered the most. Estimates suggest that approximately one million Irish people died of starvation during the famine and another million emigrated. By the end of the famine in 1852, Ireland’s population had decreased by 25%. The British government faced criticism for its inadequate response, and the catastrophe fueled the drive for Irish independence. The Irish people felt that the British had not tried hard enough to take care of the people under their rule.

As often happens when a food item is no longer allowed or readily available, the Irish people loved their potatoes. The significance of the potato in Irish culture surpasses its agricultural importance, profoundly influencing culinary customs. It turned into a dietary mainstay, with creations like colcannon (mashed potatoes with kale or cabbage), boxty (potato pancakes) being a beloved dish in my Grandma Byer’s (Aunt Sandy’s mom) home, and Irish stew (potatoes, meat, and vegetables) becoming indispensable. These dishes were not

merely nourishing but also reflected the creativity and adaptability of Irish cooks who produced a variety of meals from a few ingredients. The simple yet hearty character of these potato-centric dishes mirrored the lives and struggles of ordinary people, ingraining these recipes in the heart of Irish cooking traditions. And with that, I feel like I now understand my aunt’s obsession with potatoes.

merely nourishing but also reflected the creativity and adaptability of Irish cooks who produced a variety of meals from a few ingredients. The simple yet hearty character of these potato-centric dishes mirrored the lives and struggles of ordinary people, ingraining these recipes in the heart of Irish cooking traditions. And with that, I feel like I now understand my aunt’s obsession with potatoes.

During the Great Potato Famine of September 1845 in Ireland, the leaves on potato plants suddenly turned black and curled, then rotted, seemingly the result of a fog that had rolled across the fields of Ireland. In reality, the cause was an airborne fungus named Phytophthora Infestans. It was originally transported in the holds of ships traveling from North America to England. The resulting loss of the potato crops, put the people of Ireland in dire straits. Many people decided that it was time to immigrate to America. In fact, more than a million people immigrated to America and most settled in the coal regions of Pennsylvania. Many of the Irish Catholics immigrants were routinely met with discrimination based on both their religion and heritage. They often encountered help wanted signs with disclaimers that read, “Irish need not apply.” These days, that practice would have met with harsh retaliation due to anti-discrimination laws.

During the Great Potato Famine of September 1845 in Ireland, the leaves on potato plants suddenly turned black and curled, then rotted, seemingly the result of a fog that had rolled across the fields of Ireland. In reality, the cause was an airborne fungus named Phytophthora Infestans. It was originally transported in the holds of ships traveling from North America to England. The resulting loss of the potato crops, put the people of Ireland in dire straits. Many people decided that it was time to immigrate to America. In fact, more than a million people immigrated to America and most settled in the coal regions of Pennsylvania. Many of the Irish Catholics immigrants were routinely met with discrimination based on both their religion and heritage. They often encountered help wanted signs with disclaimers that read, “Irish need not apply.” These days, that practice would have met with harsh retaliation due to anti-discrimination laws.

I know that a number of my ancestors came from Ireland, and I would not be surprised to find that a number of my ancestors were among those immigrants that came to America to find a better life. The unfortunate thing was that the few people who would hire them, and the few places that would rent to them, were corrupt people. The immigrants finally accepted the most physically demanding and dangerous mining jobs, just to have work. The men and their families were forced to live in overcrowded housing, buy from shops, and visit doctors all “owned” by the company. In many cases, workers wound up owing their employers at the end of  each month. The Irish immigrants were in a very tough situation, but they had been there before, and they were not going to continue to be victimized.

each month. The Irish immigrants were in a very tough situation, but they had been there before, and they were not going to continue to be victimized.

The abuse triggered a period of violence in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, between 1861 and 1875. The violence which included assaults, arsons, and murders were blamed on a secret society of Irish immigrants known as the Molly Maguires. The group originally emerged in northern Ireland in the 1840s, as a branch of the long line of rural secret societies including the Whiteboys and Ribbonmen, who responded to miserable working conditions and evictions by tenant landlords with bloody vengeance. When the Civil War broke out, the Irish immigrants were drafted to serve, and they rebelled by sending out “coffin notices” threatening death, because they perceived the war to be a “rich man’s war,” and they wanted no part of it. The notes were alleged to have been written by the Molly Maguires, because they didn’t want to lose their jobs to scabs. Threats were actually carried out 24 times when foremen and supervisors were assassinated.

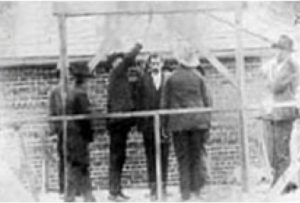

In 1873, the president of the Reading Railroad, Franklin Gowen hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to infiltrate and destroy the Molly Maguires, because their union activities were impeding that railroad’s ability to increase profits. The detective, James McParlan, used the alias, James McKenna to infiltrate the group. Oddly, he was an Irishman himself, but I guess money was more important to him. Franklin Gowen served as the chief  prosecutor, even though his railroad holdings made his participation a conflict of interest. Based almost entirely on McParlan’s testimony, 20 men were sentenced to death—10 of whom were executed on June 21, 1877, also known as Black Thursday. The men declared their innocence right up to the end. Although the existence of the Molly Maguires as an organized band of outlaws in America is under debate to this day, most historians now agree that the trials and executions were an outrageous perversion of the criminal justice system. In 1979, more than 100 years following his hanging, John Kehoe, who was the supposed “king” of the Molly Maguires, was granted a full pardon by the state of Pennsylvania.

prosecutor, even though his railroad holdings made his participation a conflict of interest. Based almost entirely on McParlan’s testimony, 20 men were sentenced to death—10 of whom were executed on June 21, 1877, also known as Black Thursday. The men declared their innocence right up to the end. Although the existence of the Molly Maguires as an organized band of outlaws in America is under debate to this day, most historians now agree that the trials and executions were an outrageous perversion of the criminal justice system. In 1979, more than 100 years following his hanging, John Kehoe, who was the supposed “king” of the Molly Maguires, was granted a full pardon by the state of Pennsylvania.