Germany

On November 19, 1941, a naval engagement took place off the coast of Western Australia between the Australian light cruiser, the HMAS Sydney, commanded by Captain Joseph Burnett, and the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran, led by Fregattenkapitän Theodor Detmers. The encounter occurred around 106 nautical miles from Dirk Hartog Island. The battle, which was a one-on-one confrontation, lasted for thirty minutes, resulting in the destruction of both vessels.

On November 19, 1941, a naval engagement took place off the coast of Western Australia between the Australian light cruiser, the HMAS Sydney, commanded by Captain Joseph Burnett, and the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran, led by Fregattenkapitän Theodor Detmers. The encounter occurred around 106 nautical miles from Dirk Hartog Island. The battle, which was a one-on-one confrontation, lasted for thirty minutes, resulting in the destruction of both vessels.

Beginning November 24th, following the failure of the Sydney to return to port, extensive air and sea searches were initiated. Survivors from the Kormoran were rescued at sea aboard boats and rafts, while others reached land at Quobba Station, situated 37 miles north of Carnarvon. In total, 318 out of the 399 Kormoran crew members survived. Debris from the Sydney was discovered, but none of the 645 crew members survived. This event marked the most devastating loss of life in the Royal Australian Navy’s history, the largest loss of an Allied warship with all hands during World War II and dealt a severe blow to Australian wartime morale. The fate of the Sydney was revealed to Australian authorities through the Kormoran survivors, who were detained in prisoner of war camps until the end of the war.

The HMAS Sydney, a Modified Leander class light cruiser, was one of three in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). It was originally constructed for the Royal Navy, but it was acquired by the Australian government as a  replacement for the HMAS Brisbane and commissioned into the RAN in September 1935. Measuring 562 feet 4 inches in length, the Sydney had a displacement of 9,080 tons (8,940 long tons). Its primary armament consisted of eight 6-inch guns across four twin turrets, designated “A” and “B” at the front and “X” and “Y” at the rear. Additionally, it was equipped with four 4-inch anti-aircraft guns, nine .303-inch machine guns, and eight 21-inch torpedo tubes arranged in two quadruple mountings. The cruiser also housed a Supermarine Walrus amphibious aircraft.

replacement for the HMAS Brisbane and commissioned into the RAN in September 1935. Measuring 562 feet 4 inches in length, the Sydney had a displacement of 9,080 tons (8,940 long tons). Its primary armament consisted of eight 6-inch guns across four twin turrets, designated “A” and “B” at the front and “X” and “Y” at the rear. Additionally, it was equipped with four 4-inch anti-aircraft guns, nine .303-inch machine guns, and eight 21-inch torpedo tubes arranged in two quadruple mountings. The cruiser also housed a Supermarine Walrus amphibious aircraft.

The Kormoran was commissioned in October 1940 and underwent modifications to reach a length of 515 feet and a gross register tonnage of 8,736. This raider was equipped with six single 5.9-inch guns…two positioned on the forecastle and quarterdeck, and the remaining two along the centerline…as its primary armament. This was complemented by two 1.46-inch anti-tank guns, five 0.79-inch anti-aircraft autocannons, and six 21-inch torpedo tubes, which included a twin above-water mount on each side and two single underwater tubes. The 5.9-inch guns were hidden behind false hull plates and cargo hatch walls that could swing open upon the command to decamouflage. The secondary armaments were mounted on hydraulic lifts concealed within the superstructure, allowing the ship to masquerade as various Allied or neutral vessels.

The battle has been the subject of much controversy, particularly in the years preceding the discovery of the two wrecks in 2008. The defeat of the purpose-built warship Sydney by the modified merchant vessel Kormoran was a topic of much speculation, inspiring numerous books and prompting two official government inquiry reports, released in 1999 and 2009.

German accounts, deemed truthful and generally accurate by Australian interrogators during the war and by most subsequent analyses, indicate that Sydney came so close to Kormoran that it forfeited the benefits of its heavier armor and superior gun range. Despite this, numerous post-war publications have speculated about an

extensive cover-up regarding Sydney’s loss, alleged violations of the laws of war by the Germans, the massacre of Australian survivors after the battle, or secret involvement by the Empire of Japan in the action (prior to its official war declaration in December). Presently, there is no evidence to substantiate these theories, leaving the battle and the loss of the two ships a mystery to this day.

extensive cover-up regarding Sydney’s loss, alleged violations of the laws of war by the Germans, the massacre of Australian survivors after the battle, or secret involvement by the Empire of Japan in the action (prior to its official war declaration in December). Presently, there is no evidence to substantiate these theories, leaving the battle and the loss of the two ships a mystery to this day.

It all happened overnight. The people of East Berlin became prisoners of their government. The government was oppressive, and people wanted to leave. The government could not have that, so walls were put up encircling the city virtually overnight. East Germany was now a part of the Eastern Bloc, and it was separated from West Germany in the Western Bloc by the inner German border and the Berlin Wall, which were heavily fortified with watchtowers, land mines, armed soldiers, and various other measures to prevent illegal crossings. The people were prisoners, and the East German border troops were instructed to prevent defection to West Germany by all means, including lethal force (Schießbefehl; “order to fire”). Many people attempted escape, and many people died trying.

It all happened overnight. The people of East Berlin became prisoners of their government. The government was oppressive, and people wanted to leave. The government could not have that, so walls were put up encircling the city virtually overnight. East Germany was now a part of the Eastern Bloc, and it was separated from West Germany in the Western Bloc by the inner German border and the Berlin Wall, which were heavily fortified with watchtowers, land mines, armed soldiers, and various other measures to prevent illegal crossings. The people were prisoners, and the East German border troops were instructed to prevent defection to West Germany by all means, including lethal force (Schießbefehl; “order to fire”). Many people attempted escape, and many people died trying.

One of the people who refused to give up and settle for imprisonment was Peter Strelzyk (born 1942), an electrician and former East German Air Force mechanic. Strelzyk, along with his friend, Günter Wetzel (born 1955), who was a bricklayer by trade, were determined to get out of East Berlin. The men had been colleagues at a local plastics factory for four years. They had long shared a desire to get out of the country and make a better life for their families. They began discussing, albeit very quietly, how they might make their escape. On March 7, 1978, they decided that they were done living that way and began to plan an escape. Their first thought was to build a helicopter. Then, they realized that they would be unable to acquire an engine capable of powering such a craft. Then, their imaginations alighted on the thought of building a hot air balloon. That idea came about after they watched a television program about ballooning. Some say that they got the idea after a relative shared a magazine article about the International Balloon Festival in Albuquerque, New Mexico. It really doesn’t matter where the idea came from, because they main thing is that they cose a hot air balloon as their escape vehicle.

The decision made, Strelzyk and Wetzel began research into balloons. The plan was to escape with their wives and a total of four children, aged 2 to 15. This was going to have to be a big balloon to hold eight passengers and the basket they would ride in. They calculated the weight of the eight passengers and the craft itself to be around 1,650 pounds. With that in mind, they knew that would need a balloon that could carry the weight would need to hold 71,000 cubic feet of air heated to 212 °F. The next calculation was the amount of material needed for the balloon itself, estimated to be 8,600 square feet.

The pair lived in Pößneck, a small town of about 20,000 where large quantities of cloth could not be obtained without raising attention. There were a number of things that raised suspicion, and a number of people in East Berlin who were all too willing to tell the authorities what they saw and heard. The two men tried neighboring towns of Rudolstadt, Saalfeld, and Jena without success. They travelled 31 miles to Gera, where they were finally able to purchase 3 feet 3 inch wide rolls of cotton cloth totaling 850 2,790 feet in length at a department store after telling the astonished clerk that they needed the large quantity of material to use as tent lining for their camping club.

Wetzel spent two weeks sewing the cloth into a balloon-shaped bag, 49 feet wide by 66 feet long, using a 40-year-old manually operated sewing machine. Strelzyk spent the time building the gondola and burner assembly. The gondola was made from an iron frame, sheet metal floor, and clothesline run around the perimeter every 5.9 inches for the sides. The burner was made using two 24-pound bottles of liquid propane household gas, hoses, water pipe, a nozzle, and a piece of stove pipe.

Finally, in April 1978, the balloon was ready to be tested. For several days, the men searched for just the right spot for the test. The site had to be secluded and yet have a good-sized clearing. They settled on a forest clearing near Ziegenrück, 6.2 miles from the border and 19 miles from Pößneck. Unfortunately, when they tried to inflate the balloon, the heated air from the burner would not move into the balloon. They thought the problem might stem from the fact that they had laid the balloon on the ground. After weeks of additional searching, they found an 82-foot cliff at a rock quarry where they could suspend the balloon vertically before inflation. Unfortunately, that plan also failed.

In the most dramatic invention to date, the men decided to fill the bag with ambient-temperature air before using the burner to raise the air temperature and provide lift. For this, the men constructed a blower with a 14 horsepower 250 cc 15 cubic inch motorcycle engine, started with a Trabant automobile starter powered by jumper cables from Strelzyk’s Moskvitch sedan. The engine, which was quieted by a Trabant muffler. The engine turned 3.3 feet fan blades to inflate the balloon. They also used a home-made flamethrower, similar to the gondola’s burner, to pre-heat the air faster. With these modifications in place, they returned to the secluded clearing to try again, and again the plan failed to inflate the balloon. At this point, they discovered that the cotton material was the problem. It was just too porous, and the heated air quickly seeped out. That unsuccessful attempt had cost them 2,400 DDM. Strelzyk disposed of the cloth by burning it in his furnace over several weeks.

The men went back to the drawing board. Strelzyk and Wetzel purchased samples of different fabrics in local stores, including umbrella material and various samples of taffeta and nylon. Then they used an oven to test the material for heat resistance. They also created a test rig from a vacuum cleaner and a water-filled glass tube to determine which material would allow the vacuum to exert the most suction on the water, and consequently which was the most impervious to air. Of the materials tested, the umbrella covering performed the best, but it was also the most expensive. In the end, they instead selected a synthetic kind of taffeta.

Once again, the men traveled to a distant city to make their purchases so they wouldn’t arouse suspicion. This time they travelled over 100 miles to a department store in Leipzig. Their new cover story was that they belonged to a sailing club and needed the material to make sails. They were extremely worried that the purchase could alert East Germany’s State Security Service (Stasi). Nevertheless, they returned the next day and picked up the material without incident. They paid 4,800 DDM (US$720) for 2,600 feet of 3-foot 3-inch  fabric. On the way home, they also purchased an electric motor to speed up the pedal-operated sewing machine they had been using to sew the material into the desired balloon shape.

fabric. On the way home, they also purchased an electric motor to speed up the pedal-operated sewing machine they had been using to sew the material into the desired balloon shape.

Wetzel spent the next week sewing the material into another balloon. The new motor made the work much faster. Before long they were ready. Soon afterwards, they returned to the forest clearing and inflated the bag in about five minutes using the blower and flame thrower. It was amazing!! Unfortunately, there was s glitch. The bag rose and held air, but the burner on the gondola was not powerful enough to create the heat needed for lift. The pair continued experimenting for months, doubling the number of propane tanks and trying different fuel mixtures. Disappointed with the result, Wetzel decided to abandon the project and instead started to pursue the idea of building a small gasoline engine-powered light aeroplane or a glider.

Strelzyk, however, refused to give up. He continued trying to improve the burner. In June 1979, he discovered that with the propane tank inverted, additional pressure caused the liquid propane to evaporate, which produced a bigger flame. He modified the gondola to mount the propane tanks upside down, and returned to the test site where he found the new configuration produced a 39-foot-long flame. Strelzyk was ready to attempt an escape.

Now down to just four people, the Strelzyk family chose July 3, 1979, and go-day. The weather and wind conditions were favorable. The entire Strelzyk family lifted from a forest clearing at 1:30 am and climbed at a rate of 13 feet per second. They reached an altitude of 6,600 feet according to an altimeter Strelzyk had made by modifying a barometer. A light wind was blowing them towards the border. The balloon then entered clouds, and atmospheric water vapor condensed on the balloon, adding weight which caused it to descend prematurely. The family landed safely…but they were approximately 590 feet short of the border, at the edge of the heavily mined border zone. It was a terrifying situation. At first, they weren’t sure where they were, but Strelzyk explored until he found a piece of litter…a bread bag from a bakery in Wernigerode, an East German town. The terrified family spent nine hours carefully extricating themselves from the 1,600-foot-wide border zone to avoid detection. They also had to travel unnoticed through a 3.1-mile restricted zone before hiking back a total of 8.7 mile to their car and the launch paraphernalia they had left behind. Amazingly, while the balloon was found, their car had not been. They made it home just in time to report absent due to sickness from work and school and go to be to get some much-needed rest.

The abandoned balloon was discovered by the authorities later that morning, and Strelzyk destroyed all compromising evidence and sold his car, fearing that it could link him to the escape attempt. On August 14th, the Stasi launched an appeal to find the “perpetrator of a serious offence” and listed in detail all the items recovered at the landing site. Strelzyk felt that the Stasi would eventually trace the balloon to him and the Wetzels. He agreed with Wetzel that their best chance was to quickly build another balloon and get out as soon as possible.

At this point, Wetzel again joined Strelzyk. They doubled the balloon’s size to 140,000 cubic feet in volume, 66 feet in diameter, and 82 feet in height. They needed 13,500 square feet of taffeta, and purchased the material, in various colors and patterns, all over the country in order to escape suspicion. Wetzel sewed a third balloon, using over 3.7 miles of thread, and Strelzyk rebuilt everything else as before. They worked feverishly, because they knew their time was very limited. The authorities were closing in on them. In six weeks, they had prepared the 400-pound balloon and a payload of 1,210 pound, including the gondola, equipment, and cargo of eight people. Confident in their calculations, they found the weather conditions right on September 15, 1978, when a violent thunderstorm created the correct winds. The two families set off for the launch site in Strelzyk’s replacement car (a Wartburg) and a moped. Arriving at 1:30 am, they needed just ten minutes to inflate the balloon and an additional three minutes to heat the air.

They lifted off just after 2:00 am, and in their hurry, the group failed to cut the tethers holding the gondola to the ground at the same time, tilting the balloon and sending the flame towards the fabric, which caught fire. They quickly got the fire out, because they had prepared for such an emergency. Then the balloon climbed to 6,600 feet in nine minutes, drifting towards West Germany at 9 miles per hour. The balloon flew for 28 minutes, with the temperature plummeting to 18 °F in the unsheltered gondola, which consisted solely of clothesline railing. Nevertheless, they pressed on.

A design miscalculation resulted in the burner stovepipe being too long, causing the flame to be too high in the balloon, creating excessive pressure which caused the balloon to split. While they had to use the burner more that they had hoped, they kept the balloon in the air. At one point, they increased the flame to the maximum possible extent and rose to 8,200 feet. They later learned they had been high enough to be detected, but not identified, on radar by West German air traffic controllers. They had also been detected on the East German side by a night watchman at the district culture house in Bad Lobenstein. The report of an unidentified flying object heading toward the border caused guards to activate search lights, but the balloon was too high and out of reach of the lights. God had protected the families.

When the propane ran out, the balloon descended quickly, landing near the town of Naila, in the West German state of Bavaria and only 6 miles from the border. The only injury was suffered by Wetzel, who broke his leg upon landing. Various clues indicated to the families that the balloon had made it across the border. These included spotting red and yellow colored lights, not common in East Germany, and small farms, in contrast to the large state-run operations in the east. Another clue was modern farm equipment, unlike the older equipment used in East Germany. Two Bavarian State Police officers saw the balloon’s flickering light and headed to where they thought it would land. There they found Strelzyk and Wetzel, who first asked if they had made it to the west, although they noticed the police car was an Audi…another sign they were in West Germany. Upon learning they had, the escapees happily called for their families to join them.

Of course, East Germany immediately increased border security, closed all small airports close to the border, and ordered the planes kept farther inland. Propane gas tanks became registered products, and large quantities of fabric suitable for balloon construction could no longer be purchased. Mail from East Germany to the two escaped families was prohibited.

Erich Strelzyk learned of his brother’s escape on the ZDF news and was arrested three hours after the landing in his Potsdam apartment. The arrest of family members was standard procedure to deter others from attempting escape. He was charged with “aiding and abetting escape”, as were Strelzyk’s sister Maria and her  husband, who were sentenced to 2½ years. The three were eventually released with the help of Amnesty International.

husband, who were sentenced to 2½ years. The three were eventually released with the help of Amnesty International.

The families decided to initially settle in Naila where they had landed. Wetzel worked as an automobile mechanic and Strelzyk opened a TV repair shop in Bad Kissingen. Due to pressure from Stasi spies, the Strelzyks moved to Switzerland in 1985. After German reunification in 1990, they returned to their old home in their hometown of Pößneck. The Wetzels remained in Bavaria. Peter Strelzyk died in 2017 at age 74 after a long illness. In 2017, the balloon was put on permanent display at the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte: Museum in Bavaria.

Understandably, the size of the various armies has grown along with human civilization. It is estimated that nearly 28 million armed forces personnel stand at the ready globally in this present day, according to the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of course, peacetime armies would likely be smaller than wartime armies. World War II saw the most soldiers ever to be amassed…with about 70 million soldiers. Approximately 42 million of those soldiers were from the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Japan. These nations armies and related services were four of the largest ever rallied to the battlefield. The largest three were the United States (12,209,000 troops in August 1945), the German Reich (12,070,000 troops in June 1944), and the Soviet Union (11,000,000 troops in June 1943). Those numbers are staggering to think about.

Understandably, the size of the various armies has grown along with human civilization. It is estimated that nearly 28 million armed forces personnel stand at the ready globally in this present day, according to the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of course, peacetime armies would likely be smaller than wartime armies. World War II saw the most soldiers ever to be amassed…with about 70 million soldiers. Approximately 42 million of those soldiers were from the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Japan. These nations armies and related services were four of the largest ever rallied to the battlefield. The largest three were the United States (12,209,000 troops in August 1945), the German Reich (12,070,000 troops in June 1944), and the Soviet Union (11,000,000 troops in June 1943). Those numbers are staggering to think about.

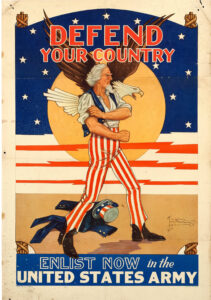

As is expected in a world war, many soldiers are needed. So, the World War II army of the US became the biggest army in history. Citizens of the United States are notorious for patriotism, when we have been attacked. It is like waking a sleeping giant, and we will retaliate with a vengeance. Due in part to that surge of American patriotism and also because of conscription (the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service,

mainly a military service), the US Army numbered 12,209,000 soldiers by the end of the war in 1945. It is little surprise that the Japanese found themselves surrendering to the United States on this day, September 2, 1945. of course, the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left little doubt that the Americans not only had the atomic bomb, but we would us it. Basically, their choices were to stay in the fight and die or surrender. They chose the latter, and the rest is history.

mainly a military service), the US Army numbered 12,209,000 soldiers by the end of the war in 1945. It is little surprise that the Japanese found themselves surrendering to the United States on this day, September 2, 1945. of course, the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left little doubt that the Americans not only had the atomic bomb, but we would us it. Basically, their choices were to stay in the fight and die or surrender. They chose the latter, and the rest is history.

In order to determine which of the armies were the largest in history, 24/7 Wall Street reviewed a list of military superpowers from Business Insider. These armies were ranked based on the total number of troops that were serving a country or empire at the point when the army was at its largest. Without doubt, the United States was, and remains to this day, the nation with the largest army in history. Over the years, the armed forces of the United States have been larger and smaller, depending on the need at the time, the administration

in charge, and since the draft was discontinued, the number of people who chose to join up to serve their country and to qualify for the GI Bill so that they can get free college. No matter how they got in the service, or how long they stayed, I am very proud of all of our soldiers over the many years of this nation…and I thank them for their service. On this day, the largest army in history accepted the surrender of the Japanese, who had once had the nerve to attack us on our own soil. That was their biggest mistake ever.

in charge, and since the draft was discontinued, the number of people who chose to join up to serve their country and to qualify for the GI Bill so that they can get free college. No matter how they got in the service, or how long they stayed, I am very proud of all of our soldiers over the many years of this nation…and I thank them for their service. On this day, the largest army in history accepted the surrender of the Japanese, who had once had the nerve to attack us on our own soil. That was their biggest mistake ever.

I think many people realize the usefulness of a dog as something other than a pet. Over the years, there have been seeing eye dogs, service dogs, and one I hadn’t heard of before…mercy dogs. During World War I, some 50,000 dogs were “employed” by both sides of the conflict as soldiers on both sides of the conflict as mercy dogs. You might wonder just what a mercy dogs is. While it is a rather sad one, the job the dogs had was actually had a very important job in the military. During battle, these dogs were sent out to find and help wounded men on the battlefield. They were very good at their jobs.

I think many people realize the usefulness of a dog as something other than a pet. Over the years, there have been seeing eye dogs, service dogs, and one I hadn’t heard of before…mercy dogs. During World War I, some 50,000 dogs were “employed” by both sides of the conflict as soldiers on both sides of the conflict as mercy dogs. You might wonder just what a mercy dogs is. While it is a rather sad one, the job the dogs had was actually had a very important job in the military. During battle, these dogs were sent out to find and help wounded men on the battlefield. They were very good at their jobs.

On their backs, the dogs carried medical supplies. They sought out injured soldiers. If a soldier was gravely wounded, the dogs would tear off a piece of his uniform, carry it back to camp, and help other soldiers to locate the man. Sometimes, the dogs found men who were beyond saving. In that case, they lay down next to him, so that the dying soldier didn’t have to die alone. These were true acts of mercy, and these dongs had true compassion for these men.

Mercy dogs were also known as ambulance dogs, Red Cross dogs, or casualty dogs. These dogs actually served in a paramedical role in the military…most notably during World War I, but also in World War II, and the Korean War. They have been credited with saving thousands of lives. The dogs were well trained and well suited for  trench warfare. They were often sent out after large battles, where they would seek out wounded soldiers. They were also trained to guide combat medics to soldiers who required extensive care.

trench warfare. They were often sent out after large battles, where they would seek out wounded soldiers. They were also trained to guide combat medics to soldiers who required extensive care.

The first mercy dogs were actually trained by the German army in the late 19th century. The program to train mercy dogs in 1895 begun by Jean Bungartz in Germany was described as a “novel experiment” by those who knew about it. I’m sure they didn’t think it would actually work. Nevertheless, by 1908, Italy, Austria, and France had joined Germany in training programs for mercy dogs. Germany had around 6,000 trained dogs by the beginning of World War I. Many of the trained dogs were ambulance dogs. The German army called them Sanitätshunde or medical dogs. Germany is estimated to have used a total of 30,000 dogs during the war, mainly as messengers and ambulance dogs. Amazingly, only 7,000 of those were killed. Somehow, I would have expected there to be more deaths among the dogs. It is estimated that upwards of 50,000 dogs were successfully used by all of the nations involved in the war.

When World War I started, Britain did not have a program for training military dogs. Edwin Hautenville Richardson, who was an officer in the British Army had experience working with military dogs and had advocated for the start of a military program since 1910, but his program was not taken seriously. Nevertheless, he had trained several dogs as ambulance dogs on his own. He quickly offered them to the British Army. The army did not accept his offer, for some bizarre reason, so he gave them to the British Red Cross. As a result of his advocacy, Britain created a British War Dog School with Richardson as the commander. The school eventually trained more than 200 dogs. The British War Dog School was a grand success.

It is estimated that as many as 10,000 dogs served as mercy dogs in World War I, and are credited with saving thousands of lives, including at least 2,000 in France and 4,000 wounded German soldiers. There were several dogs that were specifically honored for their work. “Captain” was credited for finding 30 soldiers in one day, and “Prusco” for finding 100 men in just one battle. Both of these were French dogs. “Prusco” was known to drag soldiers into ditches as a safe harbor while he went to summon rescuers. Sadly, many French dogs were killed in the line of duty, and the program was discontinued. I suppose they thought it was inhumane, but I’m sure the dogs knew they were doing important work.

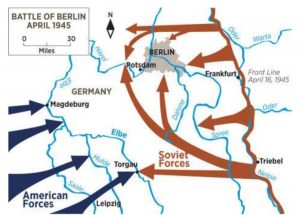

Sometimes, an event that potentially changed history, ends up getting little or no recognition. Thankfully, the picture that marked the event was taken, or the entire event might never have been noticed in history at all. This particular day is actually a very important day in the history of World War II, and therefore, the world. Elbe Day, which took place on April 25, 1945, is the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, near Torgau in Germany. This event marked an important step toward the end of World War II in Europe. If you have ever heard the saying, divide and conquer, you will know basically what happened on Elbe Day. A secret mission had been planned, and April 25, 1945, was the day it was carried out.

Sometimes, an event that potentially changed history, ends up getting little or no recognition. Thankfully, the picture that marked the event was taken, or the entire event might never have been noticed in history at all. This particular day is actually a very important day in the history of World War II, and therefore, the world. Elbe Day, which took place on April 25, 1945, is the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, near Torgau in Germany. This event marked an important step toward the end of World War II in Europe. If you have ever heard the saying, divide and conquer, you will know basically what happened on Elbe Day. A secret mission had been planned, and April 25, 1945, was the day it was carried out.

The plan was to have the Soviet army advance from the East, and the US Army advance from the West. The first contact between American and Soviet patrols occurred near Strehla exactly as planned, after First Lieutenant Albert Kotzebue, an American soldier, crossed the Elbe River in a boat with three men of an intelligence and reconnaissance platoon. Once they crossed to the east bank of the river, they met up with  forward elements of a Soviet Guards rifle regiment of the First Ukrainian Front, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Gardiev. Later that day, another patrol under Second Lieutenant William Robertson with Frank Huff, James McDonnell and Paul Staub met a Soviet patrol commanded by Lieutenant Alexander Silvashko on the destroyed Elbe bridge of Torgau. When the two armies connected at the Elbe River, the cutting of Germany in half is accomplished. In doing so, the strength of the German army was severely weakened. The German army was split in two, just like the country was, and in the end, that split made it impossible for the Germans to really fight the war they were engaged in. It was the beginning of the end for them.

forward elements of a Soviet Guards rifle regiment of the First Ukrainian Front, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Gardiev. Later that day, another patrol under Second Lieutenant William Robertson with Frank Huff, James McDonnell and Paul Staub met a Soviet patrol commanded by Lieutenant Alexander Silvashko on the destroyed Elbe bridge of Torgau. When the two armies connected at the Elbe River, the cutting of Germany in half is accomplished. In doing so, the strength of the German army was severely weakened. The German army was split in two, just like the country was, and in the end, that split made it impossible for the Germans to really fight the war they were engaged in. It was the beginning of the end for them.

Finally, on April 26, the commanders of the 69th Infantry Division of the First Army (United States) and the 58th Guards Rifle Division of the 5th Guards Army (Soviet Union) met at Torgau, southwest of Berlin. They knew that this moment was monumental, and it had to be documented. Arrangements were made for the  formal “Handshake of Torgau” photo to be taken of Robertson and Silvashko the following day, April 27. The Soviet, American, and British governments released simultaneous statements that evening in London, Moscow, and Washington, “reaffirming the determination of the three Allied powers to complete the destruction of the Third Reich.” They knew they must have victory at all costs.

formal “Handshake of Torgau” photo to be taken of Robertson and Silvashko the following day, April 27. The Soviet, American, and British governments released simultaneous statements that evening in London, Moscow, and Washington, “reaffirming the determination of the three Allied powers to complete the destruction of the Third Reich.” They knew they must have victory at all costs.

The fact that Elbe Day has never been an official holiday in any country, has not stopped people from looking to the day as something very special, and in the years after 1945 the memory of this friendly encounter gained new significance in the context of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

There are some national events that stay in our thoughts and hearts forever. The Pearl Harbor is one of those events. The attack on Pearl Harbor was so destructive and so unexpected that it shocked everyone…well, most everyone anyway. President Franklin D Roosevelt knew that Japan would likely attack, but thought it would be in the western Pacific Ocean, especially the Philippians. Pearl Harbor was considered an unlikely target. Roosevelt wanted to enter the war, but he wanted to attack Germany, whom he considered to be the bigger threat. In fact, he had ordered the attack on any U-Boats found in the west side of the Atlantic. So, technically the US was already in the war…most people just didn’t know that. Still, the attack on Pearl Harbor was horrific and the United States had to retaliate.

There are some national events that stay in our thoughts and hearts forever. The Pearl Harbor is one of those events. The attack on Pearl Harbor was so destructive and so unexpected that it shocked everyone…well, most everyone anyway. President Franklin D Roosevelt knew that Japan would likely attack, but thought it would be in the western Pacific Ocean, especially the Philippians. Pearl Harbor was considered an unlikely target. Roosevelt wanted to enter the war, but he wanted to attack Germany, whom he considered to be the bigger threat. In fact, he had ordered the attack on any U-Boats found in the west side of the Atlantic. So, technically the US was already in the war…most people just didn’t know that. Still, the attack on Pearl Harbor was horrific and the United States had to retaliate.

The attack on Pearl Harbor took so many people by surprise. It was a Sunday morning, and many of the military personnel were off base attending church services. The Japanese knew that the ships, planes, and the base in general would be seriously understaffed at the time of the attack. Of course, on the flip side, the fact that so many of the military personnel were away from the base at the time of the attack, meant that the base was able to get back up and running quickly and when we did enter the war, the Japanese were surprised about the attacks coming back at them. Of course, as we all know, the Allies went on to win the war against the Axis nation, including Germany and Japan. It’s been said that people shouldn’t wake the sleeping giant, and that is a wise statement. The Japanese awakened the United States to the fact that appeasing your enemies will not prevent an attack. It takes a show of military might to inform our enemies that it is wise to back away and let the sleeping giants lie.

Of course, the victory that was won following the attack of Pearl Harbor and the US entrance into World War II, came at a high price. A total of 2,403 people (both civilians and soldiers), not to mention ships, airplanes, and

other military equipment. After the attack, the people of the United States were…angry!! We quickly geared up and the war was on for the United States. Our delay could never bring back the people we lost, but we would certainly avenge their loss. Today we remember those we lost, and those who went out to take up the fight to protect our country from such a horrendous attack.

other military equipment. After the attack, the people of the United States were…angry!! We quickly geared up and the war was on for the United States. Our delay could never bring back the people we lost, but we would certainly avenge their loss. Today we remember those we lost, and those who went out to take up the fight to protect our country from such a horrendous attack.

For most of us, who took gymnastics in school or other training, our school years coming to an end, usually also ends our “gymnastics career,” if it could be called that. There are some gymnasts who continue on in their career or even go on to the Olympics, but even then, most of them are finished with their gymnastics career by their late teens or early twenties. Let’s face it, gymnastics is a strenuous career, and most people just can’t take the strain very late in life or even past their very early lives. There are a few, however, who are active into their mid to late thirties, and one, Oksana Chusovitina, who is currently still active at 48 years old. Nevertheless, Chusovitina is nowhere near the oldest active gymnast.

For most of us, who took gymnastics in school or other training, our school years coming to an end, usually also ends our “gymnastics career,” if it could be called that. There are some gymnasts who continue on in their career or even go on to the Olympics, but even then, most of them are finished with their gymnastics career by their late teens or early twenties. Let’s face it, gymnastics is a strenuous career, and most people just can’t take the strain very late in life or even past their very early lives. There are a few, however, who are active into their mid to late thirties, and one, Oksana Chusovitina, who is currently still active at 48 years old. Nevertheless, Chusovitina is nowhere near the oldest active gymnast.

Johanna Quaas, who is finally “rumored” to have retired, was born November 25, 1925. She is a German gymnast who was certified by Guinness World Records April 12, 2012, as the world’s oldest active competitive gymnast. At that time, she was 86 when she broke the record. She was a regular competitor in the amateur competition Landes-Seniorenspiele (State Senior Games) in Saxony. She became known worldwide on March 26, 2012, when YouTube user LieveDaffy uploaded two videos of Quaas performing gymnastics routines…one on the parallel bars and one on the floor. Prior to that video, the tiny, 5’2″ gymnast was relatively unknown, but as the clips went viral, within six days of posting and had generated over 1.1 million views each, that all changed. In addition to being recognized by Guinness World Records, Quaas has received the Nadia Com?neci Sportsmanship Award from the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame. Being an active gymnast at 86 is unheard of, and yet, Quaas continued to compete until she suffered a torn biceps tendon in 2018, while trying to help her granddaughter. Of the incident, “She just wanted to adjust a baby chair  for her granddaughter, but the ‘nipple just wouldn’t go through the flap’ – a jerk and jerk – a severe pain in her left arm led to the above diagnosis! That hurt, of course,” said the still active senior athlete, “but strangely enough, I can now raise my arm a lot better than before, and the doctor said, let’s leave it that way for now!” Technically, she stopped performing active or competitive gymnastics. Nevertheless, in addition to fact that she can actually raise her arm better than before, she could still stand on her head at age 95. Still unable to slow down really, she has developed a bed gymnastics routine which she performs every morning and has made the routine available on YouTube and DVD published by Wissner-Bosserhoff. So, has she completely retired? Only time will tell.

for her granddaughter, but the ‘nipple just wouldn’t go through the flap’ – a jerk and jerk – a severe pain in her left arm led to the above diagnosis! That hurt, of course,” said the still active senior athlete, “but strangely enough, I can now raise my arm a lot better than before, and the doctor said, let’s leave it that way for now!” Technically, she stopped performing active or competitive gymnastics. Nevertheless, in addition to fact that she can actually raise her arm better than before, she could still stand on her head at age 95. Still unable to slow down really, she has developed a bed gymnastics routine which she performs every morning and has made the routine available on YouTube and DVD published by Wissner-Bosserhoff. So, has she completely retired? Only time will tell.

Johanna Geißler was born November 20, 1925, in Hohenmölsen, Germany. She was always an active child. She often climbed tall bars and roll on the mats. She began gymnastics at an early age and loved it immediately. She first competed at about age ten, but soon her family moved to a different part of Germany, temporarily ending her participation in competitions. When she was eleven, she began Nazi Germany’s required social  service work for girls during World War II during which she worked in farming and took care of the children of another family. After completing the compulsory social service, she trained as a gymnastics coach in Stuttgart, finishing in 1945 and moving to Weißenfels. She was still unable to work in gymnastics at that time, because it had been banned in East Germany during the first two years of post-World War II Allied occupation. So, she took up team handball instead, while in Weißenfels, learning and practicing it until the ban on gymnastics was removed in 1947. In 1950, she studied at the University of Halle to become a sports teacher. She has been an active athlete all her life, and it’s been a very long and healthy life. Today, Johanna Quaas is 98 years old. Happy birthday to this amazing lady.

service work for girls during World War II during which she worked in farming and took care of the children of another family. After completing the compulsory social service, she trained as a gymnastics coach in Stuttgart, finishing in 1945 and moving to Weißenfels. She was still unable to work in gymnastics at that time, because it had been banned in East Germany during the first two years of post-World War II Allied occupation. So, she took up team handball instead, while in Weißenfels, learning and practicing it until the ban on gymnastics was removed in 1947. In 1950, she studied at the University of Halle to become a sports teacher. She has been an active athlete all her life, and it’s been a very long and healthy life. Today, Johanna Quaas is 98 years old. Happy birthday to this amazing lady.

When the Germans surrendered at the end of World War II, Germany was divided into four areas of control by the Allied Powers…Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. That gave those four countries governing control over their own sections of Germany, and the people in those areas. Not every country was exactly planning to do what the people might consider to be their best interests. The Allied countries had the control and the ability to dish out punishment as they saw fit. The Soviet Union considered the forced labor of Germans as part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. They wanted to exact some measure of revenge, I guess, and they were in a position to make that happen.

When the Germans surrendered at the end of World War II, Germany was divided into four areas of control by the Allied Powers…Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. That gave those four countries governing control over their own sections of Germany, and the people in those areas. Not every country was exactly planning to do what the people might consider to be their best interests. The Allied countries had the control and the ability to dish out punishment as they saw fit. The Soviet Union considered the forced labor of Germans as part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. They wanted to exact some measure of revenge, I guess, and they were in a position to make that happen.

So, the Soviet authorities deported German civilians from Germany and Eastern Europe to the USSR after World  War II as forced laborers. It almost reminds me of what happened with the Holocaust, except that the Soviet Union had no interest in killing their captives. They wanted slave labor and a measure of retaliation. Ethnic Germans living in the USSR were conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

War II as forced laborers. It almost reminds me of what happened with the Holocaust, except that the Soviet Union had no interest in killing their captives. They wanted slave labor and a measure of retaliation. Ethnic Germans living in the USSR were conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

The decision was made and the fate of the German people was sealed. In 1946, the Soviet Union forcibly relocated more than 2,500 former Nazi German specialists, including scientists, engineers, and technicians who worked in specialist areas, from companies and institutions relevant to military and economic policy in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany (SBZ) and Berlin, along with around 4,000 family members, totaling more than 6,000 people, to the Soviet Union as war reparations. These specialists with all of their knowledge and abilities, could easily change the course of history in the Soviet Union, or any country they were placed in, for that matter. Still, not all of the forced labor were specialists. Many were unskilled labor, doing menial jobs.

The good thing was that the situation in Germany after World War II was appalling. Many of the people were homeless from the bombings. I suppose that, for that reason, the forced move, while scary, was not the worst thing in the world. It was possible that a new life in the Soviet Union could be favorable when compared to war-torn Germany. It is unclear whether any Germans who were sent to the Soviet Union chose to go back to Germany, because information about forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union was suppressed in the Eastern Bloc until after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Many of those records could have also been destroyed.

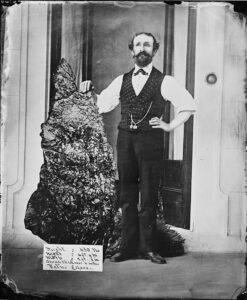

Bernhardt Otto Holtermann, who was born on April 29, 1838, was a prospector who owned part of an Australian claim where rich veins of gold were discovered after years of dry digging. I suppose it does take perseverance to successfully mine for gold, but when you consider that Holtermann finally discovered gold afteryears of digging, I would say that mining for gold also takes faith. Holtermann was born in Germany, and at adulthood set sail for Sydney, Australia in order to avoid military service. Most of his mining years were unsuccessful, including the year he even blew himself up with a premature explosion of blasting powder. Of course, his accidental explosion did not kill him, and must not have been very strong, because at the time of his greatest find, he still had all his limbs.

Bernhardt Otto Holtermann, who was born on April 29, 1838, was a prospector who owned part of an Australian claim where rich veins of gold were discovered after years of dry digging. I suppose it does take perseverance to successfully mine for gold, but when you consider that Holtermann finally discovered gold afteryears of digging, I would say that mining for gold also takes faith. Holtermann was born in Germany, and at adulthood set sail for Sydney, Australia in order to avoid military service. Most of his mining years were unsuccessful, including the year he even blew himself up with a premature explosion of blasting powder. Of course, his accidental explosion did not kill him, and must not have been very strong, because at the time of his greatest find, he still had all his limbs.

Holtermann’s “claim to fame” gold nugget was the largest gold specimen ever found, 59 inches long, weighing 630 pounds, and with an estimated gold content of 3,000 troy ounces. It was found at Hill End, near Bathurst, New South Wales. The nugget brought him enough wealth to build a mansion in North Sydney. Today, the mansion is one of the boarding houses at Sydney Church of England Grammar School (known as the Shore school). While working with one of his partners and later brother-in-law, Ludwig Hugo ‘Louis’ Beyers in their Star of Hope Gold Mining Company, in which he and Beyers were among the partners, they struck it rich. On February 22, 1868, Holtermann married Harriett Emmett, while Beyers married her sister Mary. On October 19, 1872, the Holtermann Nugget was discovered. While it was not “strictly speaking” a nugget, it was a gold specimen, a mass of gold embedded in rock, in this case quartz. Holtermann attempted to buy the 3,000-troy-ounce specimen from the company, offering £1000 over its estimated value of £12,000 (about AU$1.9 million in 2016 currency, AU$4.8 million on the 2017 gold price),  but was turned down, and the nugget was sent away to have the gold extracted. Holtermann was so upset about that, that resigned from the company in February 1873.

but was turned down, and the nugget was sent away to have the gold extracted. Holtermann was so upset about that, that resigned from the company in February 1873.

Holtermann did manage to get a photograph of himself with the nugget. This famous photo of Holtermann next to a giant “nugget” was taken by an unknown photographer. After leaving the Star of Hope Gold Mining Company, Holtermann was elected as a member for Saint Leonard’s parliament in 1882. Tragically, at the young age of just 47 years, Holtermann died in Sydney, Australia on his birthday, April 29, 1885, of “cancer of the stomach, cirrhosis of the liver, and dropsy.” He left behind his wife, three sons, and two daughters.

In every army, navy, and air force, there are exceptional soldiers…even among the enemy. During World War II, the German Luftwaffe had an incredible pilot. His name was Erich Rudorffer, and he is credited with shooting down thirteen Soviet aircraft in a single mission on October 11, 1943. In that historic mission while flying an FW-190, Rudorffer downed eight Yak-7s and five Yak-9s of the Soviet Air Force. He eventually shot down 222 enemy aircraft and ended up his combat career flying the Messerschmitt ME-262, the first operational jet fighter.

In every army, navy, and air force, there are exceptional soldiers…even among the enemy. During World War II, the German Luftwaffe had an incredible pilot. His name was Erich Rudorffer, and he is credited with shooting down thirteen Soviet aircraft in a single mission on October 11, 1943. In that historic mission while flying an FW-190, Rudorffer downed eight Yak-7s and five Yak-9s of the Soviet Air Force. He eventually shot down 222 enemy aircraft and ended up his combat career flying the Messerschmitt ME-262, the first operational jet fighter.

Still, it wasn’t just the number of planes he shot down that made him remarkable. It was also the fact that he managed to survive the war despite flying over 1000 missions and being shot down an incredible 16 times. He was even forced to parachute from his stricken fighter planes 9 of those times. Not just a Soviet killer, Rudorffer also shot down 86 aircraft operated by Western Allied air forces. He became a commercial pilot after World War II.

Rudorffer was born on November 1, 1917, in Zwochau, which was a part of the Kingdom of Saxony of the German Empire at that time. Strangely, or maybe not, very little is said or known about his parents. That was typical of the German leadership of that era. They felt like the state, and not the parents should raise the children, because…well, parents had no training in such things. Not that the German leadership did either, but they decided that they knew more than the parents, so they pulled the children from their parents’ homes and put them in boarding schools to “train” them in the German ways. After his graduation from school, Rudorffer received a vocational education as an automobile metalsmith specialized in coachbuilding, which was likely another of the German or “Nazi” way of deciding the course of the lives of the children. He might have stayed a mechanic were it not for World War I. “Rudorffer joined the military service of the Luftwaffe with Flieger-Ersatz-Abteilung 61 (Flier Replacement Unit 61) in Oschatz on April 16, 1936. From September 2 to October 15, 1936, he served with Kampfgeschwader 253 (KG 253—253rd Bomber Wing) and from October16, 1936 to February 24, 1937, he was trained as an aircraft engine mechanic at the Technische Schule Adlershof, the technical school at Adlershof in Berlin. On March 14, 1937, Rudorffer was posted to Kampfgeschwader 153 (KG 153—153rd Bomber Wing), where he served as a mechanic until end October 1938. After that, he was transferred to Flieger-Ersatz-Abteilung 51 (Flier Replacement Unit 51) based at Liegnitz in Silesia, present-day Legnica in Poland, for flight training. Rudorffer was first trained as a bomber pilot and then as a Zerstörer, a heavy fighter or destroyer, pilot. In the winter of 1944 Rudorffer was trained on the ME 262 jet fighter. In February 1945, he was recalled to command I. Gruppe JG 7 “Nowotny” from Major Theodor Weissenberger who replaced Steinhoff as Geschwaderkommodore. Rudorffer claimed 12 victories with the ME 262, to bring his total to 222. His tally  included 136 on the Eastern Front, 26 in North Africa, and 60 on the Western Front including 10 heavy bombers.”

included 136 on the Eastern Front, 26 in North Africa, and 60 on the Western Front including 10 heavy bombers.”

After the war ended, Rudorffer started out flying DC-2s and DC-3s in Australia. Later, he worked for Pan Am and the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt, Germany’s civil aviation authority. Rudorffer was honored as one of the characters in the 2007 Finnish war movie “Tali-Ihantala 1944.” A FW 190 participated, painted in the same markings as Rudorffer’s aircraft in 1944. The aircraft, now based at Omaka Aerodrome in New Zealand, still wears the colors of Rudorffer’s machine. Rudorffer died in April 2016 at the age of 98. At the time of his death, he was the last living recipient of the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords.