fur traders

Shortly after President Thomas Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase from France, which made it an American territory, William Ashley, who was a Virginia native, made the decision to move to Missouri. Ashley was a young man, who was looking to make a name for himself. He entered into a partnership with Andrew Henry to manufacture gunpowder and lead. Opportunists, Ashley and Henry took advantage of the fact that these two commodities were in short supply in young America.

Shortly after President Thomas Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase from France, which made it an American territory, William Ashley, who was a Virginia native, made the decision to move to Missouri. Ashley was a young man, who was looking to make a name for himself. He entered into a partnership with Andrew Henry to manufacture gunpowder and lead. Opportunists, Ashley and Henry took advantage of the fact that these two commodities were in short supply in young America.

Ashley’s business prospered during the War of 1812, and he also joined the Missouri militia. He eventually achieved the rank of general. When Missouri became a state in 1822, Ashley used his military fame, and his business success to win election at lieutenant governor. Once elected, Ashley set about looking for opportunities to enrich both Missouri and his own pocketbook. Because he knew the area, he realized that Saint Louis was in a perfect place to exploit the fur trade on the upper Missouri River.

Ashley recruited his old business partner, Henry to join him in this new venture. Then, Ashley placed an advertisement in the Missouri Gazette and Public Advisor seeking 100 “enterprising young men” to engage in fur trading on the Upper Missouri. The advertisement was a big success. Scores of young men responded and came to Saint Louis. Among them were such future legendary mountain men as Jedediah Smith and Jim Bridger, as well as the famous river man Mike Fink. In time, these men and dozens of others would go on to uncover many of the geographic mysteries of the Far West, but for now they were looking to make a living trapping animals for their furs.

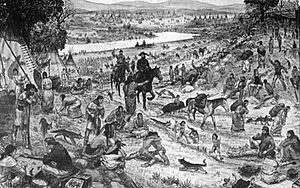

1822 found Ashley and a small band of his fur trappers building a trading post on the Yellowstone River in Montana in order to expand outward from the Missouri River. The Arikara Indians didn’t like this invasion, and they were deeply hostile to Ashley’s attempts to undercut their long-standing position as middlemen in the fur trade. The ensuing attacks eventually forced the men to abandon the Yellowstone post. Out of desperation, Ashley hit on a new strategy. Instead of building central permanent forts along the major rivers, he decided to send his trappers overland in small groups traveling by horseback. By avoiding the river arteries, the trappers could both escape detection by hostile Indians and develop new and untapped fur regions. Almost by accident, Ashley invented the famous “rendezvous” system that revolutionized the American fur trade. The necessary supplies were delivered and furs were delivered at meetings in a large meadow near the Henry’s Fork of Wyoming’s Green River in the early summer of 1825.

Ashley’s first fur trapper rendezvous was very successful. Ashley took home a tidy profit for his efforts. The fur  trappers not only had an opportunity to trade for supplies, but a chance to enjoy a few weeks of often drunken socializing. Ashley organized a second highly profitable rendezvous in 1826, and then decided to sell out. While he was no longer a part of it, his rendezvous system continued to be used by others. The system eventually became the foundation for the powerful Rocky Mountain Fur Company. With plenty of money in the bank, Ashley was able to return to his first love…politics. He was elected to Congress three times and once to the Senate, where he helped further the interests of the western land that had made him rich.

trappers not only had an opportunity to trade for supplies, but a chance to enjoy a few weeks of often drunken socializing. Ashley organized a second highly profitable rendezvous in 1826, and then decided to sell out. While he was no longer a part of it, his rendezvous system continued to be used by others. The system eventually became the foundation for the powerful Rocky Mountain Fur Company. With plenty of money in the bank, Ashley was able to return to his first love…politics. He was elected to Congress three times and once to the Senate, where he helped further the interests of the western land that had made him rich.

When the colonists came over to the new world, they really didn’t know how they were going to make a living. They were most likely planning to raise their own crops, along with hunting and fishing, but the reality is that those things were only going to take them so far. They were going to need other things. In 1620, Plymouth Colony was founded in present-day Massachusetts. The settlers there had planned to make a living with cod fishing, but that wasn’t going very well. So, within a few years of their first fur export, the Plymouth colonists began concentrating entirely on the fur trade. They developed an economic system in which their chief crop, Indian corn, was traded with Native Americans to the north for highly valued beaver skins, which were then sold in England to pay the Plymouth Colony’s debts and buy necessary supplies.

When the colonists came over to the new world, they really didn’t know how they were going to make a living. They were most likely planning to raise their own crops, along with hunting and fishing, but the reality is that those things were only going to take them so far. They were going to need other things. In 1620, Plymouth Colony was founded in present-day Massachusetts. The settlers there had planned to make a living with cod fishing, but that wasn’t going very well. So, within a few years of their first fur export, the Plymouth colonists began concentrating entirely on the fur trade. They developed an economic system in which their chief crop, Indian corn, was traded with Native Americans to the north for highly valued beaver skins, which were then sold in England to pay the Plymouth Colony’s debts and buy necessary supplies.

In November 9, 1621, Robert Cushman a deacon and captain of the Fortune arrived with 35 new settlers for Plymouth Colony…the first new colonists since the settlement was founded over a year earlier. The plan was to drop off the settlers, and then a month later, head back to England with a cargo of furs to pay for supplies and to pay debts the colony owed to England. On December 13, 1621, Robert Cushman and the Fortune set sail back to England, but theirs was not to be a good voyage. During Cushman’s return to England, the Fortune was  captured by the French, and its valuable cargo of furs was taken. Cushman was detained on the Ile d’Dieu before being returned to England. The capture was due to a navigation error. About January 19, 1622, Fortune was overtaken and seized by a French warship, with those on board being held under guard in France for about a month and with its cargo taken. Fortune finally arrived back in the Thames on February 17, 1622.

captured by the French, and its valuable cargo of furs was taken. Cushman was detained on the Ile d’Dieu before being returned to England. The capture was due to a navigation error. About January 19, 1622, Fortune was overtaken and seized by a French warship, with those on board being held under guard in France for about a month and with its cargo taken. Fortune finally arrived back in the Thames on February 17, 1622.

The Fortune was 1/3 the size of the Mayflower, displacing 55 tons. The arrival of the vessel sent by the English investors, who had funded the Mayflower colonists, should have been a cause for celebration. But for the Pilgrims, Fortune was poorly named. The ship brought 35 new settlers, but none of the expected supplies. With new mouths to feed, rations were reduced by half. Worse, the investors demanded that the ship return immediately to England, stocked with trade goods. The Pilgrims complied by loading Fortune with “good clapboard as full as she could stow” and two hogsheads of beaver and otter skins, only to have them lost to the French, which the English investors did not seem to care about.

After the Mayflower brought the Plymouth settlers, they struggled under the demands of their English investors for seven years. The investors also sent a letter criticizing the settlers because the Mayflower arrived back in England with an empty hold, and demanding that the Fortune return immediately filled with valuable goods. The colonists complied. For the next six years, they sent sizable shipments, especially of furs, back to England. But the goods yielded far less profit than the investors expected, and as the seven year mark approached, the colonists were still in debt. Finally, 27 of them pooled their personal resources and paid off the debt. Once free of the requirement to live communally and hold all property in common, the original settlers divided the land into private lots, and the era of the “Old Comers” was over.

After the Mayflower brought the Plymouth settlers, they struggled under the demands of their English investors for seven years. The investors also sent a letter criticizing the settlers because the Mayflower arrived back in England with an empty hold, and demanding that the Fortune return immediately filled with valuable goods. The colonists complied. For the next six years, they sent sizable shipments, especially of furs, back to England. But the goods yielded far less profit than the investors expected, and as the seven year mark approached, the colonists were still in debt. Finally, 27 of them pooled their personal resources and paid off the debt. Once free of the requirement to live communally and hold all property in common, the original settlers divided the land into private lots, and the era of the “Old Comers” was over.

Most people know that with an earthquake underwater, comes the possibility of a tsunami. Tsunamis can cause as much or more damage that the original earthquake. I think we all know that living in a coastal area puts the residents in possible danger when these offshore earthquakes hit, but what happens further inland? The tsunami doesn’t normally travel too far inland…unless it is a fluvial tsunami. This was a type of tsunami I had never heard of before. Nevertheless, on this day, February 7, 1812, there was a series of earthquakes in Missouri. They were the most violent and powerful quakes in the history of the United States. The series of tremors, which took place between December 1811 and March 1812. The Seismic activity was quite unusual for the area around the city of New Madrid, located near the Mississippi River in present day Arkansas, which had about 1,000 residents at the time, most of whom were farmers, hunters, and fur trappers. It all began on December 15, 1811with unusual tremors. Then, at 7:15am, an even more powerful quake erupted, now estimated to have been an 8.6 magnitude quake. This quake literally knocked people off their feet and many people experienced nausea from the extensive rolling of the earth. Given that the area was sparsely populated and there weren’t many multi-story structures, the death toll was relatively low. However, the quake did cause landslides that destroyed several communities, including Little Prairie, Missouri.

Most people know that with an earthquake underwater, comes the possibility of a tsunami. Tsunamis can cause as much or more damage that the original earthquake. I think we all know that living in a coastal area puts the residents in possible danger when these offshore earthquakes hit, but what happens further inland? The tsunami doesn’t normally travel too far inland…unless it is a fluvial tsunami. This was a type of tsunami I had never heard of before. Nevertheless, on this day, February 7, 1812, there was a series of earthquakes in Missouri. They were the most violent and powerful quakes in the history of the United States. The series of tremors, which took place between December 1811 and March 1812. The Seismic activity was quite unusual for the area around the city of New Madrid, located near the Mississippi River in present day Arkansas, which had about 1,000 residents at the time, most of whom were farmers, hunters, and fur trappers. It all began on December 15, 1811with unusual tremors. Then, at 7:15am, an even more powerful quake erupted, now estimated to have been an 8.6 magnitude quake. This quake literally knocked people off their feet and many people experienced nausea from the extensive rolling of the earth. Given that the area was sparsely populated and there weren’t many multi-story structures, the death toll was relatively low. However, the quake did cause landslides that destroyed several communities, including Little Prairie, Missouri.

The quake also caused fissures…some as much as several hundred feet long…to open on the earth’s surface. Large trees were snapped in two. Sulfur leaked out from underground pockets and river banks vanished, flooding thousands of acres of forests. On January 23, 1812, an estimated 8.4-magnitude quake struck in  nearly the same location, causing disastrous effects. Reportedly, the president’s wife, Dolley Madison, was awoken by the quake in Washington, DC. The death toll was smaller for this quake, because most of the survivors of the first earthquake were now living in tents, so they could not be crushed. The strongest of the tremors followed on February 7, 1812, and was estimated at an amazing 8.8 magnitude…probably one of the strongest quakes in human history. Church bells rang thousands of miles away in Boston, Massachusetts, from the shaking. Brick walls were toppled in Cincinnati, Ohio. In the Mississippi River, water turned brown and whirlpools developed suddenly from the depressions created in the riverbed. Waterfalls were created in an instant and in one report, 30 boats were helplessly thrown over falls, killing the people on board. Many of the small islands in the middle of the river, often used as bases by river pirates, permanently disappeared…possibly a poetic end to their crimes. Large lakes, such as Reelfoot Lake in Tennessee and Big Lake at the Arkansas-Missouri border, were created by the earthquake as river water poured into new depressions in the ground. But, probably the most unusual activity, was what happened to the Mississippi River next. Because of the quake’s proximity to the Mississippi River, the quake had an effect that was probably unheard of until that time…a Fluvial Tsunami. A Fluvial Tsunami is something I never knew existed, but apparently it does. The quake and the ensuing fluvial tsunami in the Mississippi River, actually made the river run backward for several hours. I’m sure people were stunned and frightened at what they saw.

nearly the same location, causing disastrous effects. Reportedly, the president’s wife, Dolley Madison, was awoken by the quake in Washington, DC. The death toll was smaller for this quake, because most of the survivors of the first earthquake were now living in tents, so they could not be crushed. The strongest of the tremors followed on February 7, 1812, and was estimated at an amazing 8.8 magnitude…probably one of the strongest quakes in human history. Church bells rang thousands of miles away in Boston, Massachusetts, from the shaking. Brick walls were toppled in Cincinnati, Ohio. In the Mississippi River, water turned brown and whirlpools developed suddenly from the depressions created in the riverbed. Waterfalls were created in an instant and in one report, 30 boats were helplessly thrown over falls, killing the people on board. Many of the small islands in the middle of the river, often used as bases by river pirates, permanently disappeared…possibly a poetic end to their crimes. Large lakes, such as Reelfoot Lake in Tennessee and Big Lake at the Arkansas-Missouri border, were created by the earthquake as river water poured into new depressions in the ground. But, probably the most unusual activity, was what happened to the Mississippi River next. Because of the quake’s proximity to the Mississippi River, the quake had an effect that was probably unheard of until that time…a Fluvial Tsunami. A Fluvial Tsunami is something I never knew existed, but apparently it does. The quake and the ensuing fluvial tsunami in the Mississippi River, actually made the river run backward for several hours. I’m sure people were stunned and frightened at what they saw.

The exact death toll from this series of deadly quakes is difficult to determine because of a lack of an accurate record of the Native American population in the area at the time. The series of quakes ended in March of 1812, with aftershocks continuing for years. In the end, it was decided that approximately 1,000 people died because of the quakes, but it could be much higher. As I researched this crazy tsunami, I found out that fluvial refers to a river tsunami, the Mississippi River has actually flowed backward multiple times, and fluvial tsunamis are actually not that rare, they occur whenever a quake causes the water in a river to flow backward it rush in is normal direction.