first responders

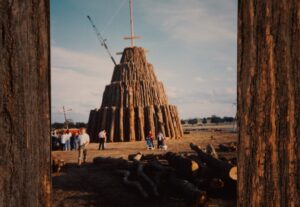

Sometimes, traditions get out of hand, and have to be called off. Such was the case with the Texas A&M University’s annual bonfire. Bonfires have long been associated with high school and college football games, usually for homecoming or the school’s main rival. The bonfire at Texas A&M was a student-built project, that became more and more elaborate every year. The bonfire being built on November 18, 1999, was probably the most elaborate and tallest bonfire structure ever. The 1999 bonfire was supposed to require more than 7,000 logs and was the labor of up to 70 workers at a time. The students had worked all night, and at approximately 2:42am, with a number of students on top of the structure, which at 59 feet high, was actually 4 feet taller than was authorized, the structure collapsed. According to Jenny Callaway, a student survivor working near the top of the stack, “It just snapped.” They had no warning. There was no audible sound, or if there was, it could not be heard over all the chatter. Dozens of students became caught in the huge log pile. Other students, such a Caleb Hill, were relatively unhurt in their 50-foot fall. At the time of the collapse, approximately 5,000 of the planned 7,000 logs were in place. Emergency medical technicians and trained first responders of the Texas A&M Emergency Care Team (TAMECT) rushed to the scene. A student-run volunteer service, who staffed each stage of construction, also began administering first aid to the victims who were thrown clear. TAMECT also alerted the University Police and University EMS, who dispatched all remaining university medics, and requested mutual aid from surrounding agencies. In addition to the mutual aid received from the College Station and Bryan, Texas EMS, Fire, and Police Departments, the members of Texas Task Force 1, the state’s elite emergency response team, were also dispatched to assist the rescue efforts.

Sometimes, traditions get out of hand, and have to be called off. Such was the case with the Texas A&M University’s annual bonfire. Bonfires have long been associated with high school and college football games, usually for homecoming or the school’s main rival. The bonfire at Texas A&M was a student-built project, that became more and more elaborate every year. The bonfire being built on November 18, 1999, was probably the most elaborate and tallest bonfire structure ever. The 1999 bonfire was supposed to require more than 7,000 logs and was the labor of up to 70 workers at a time. The students had worked all night, and at approximately 2:42am, with a number of students on top of the structure, which at 59 feet high, was actually 4 feet taller than was authorized, the structure collapsed. According to Jenny Callaway, a student survivor working near the top of the stack, “It just snapped.” They had no warning. There was no audible sound, or if there was, it could not be heard over all the chatter. Dozens of students became caught in the huge log pile. Other students, such a Caleb Hill, were relatively unhurt in their 50-foot fall. At the time of the collapse, approximately 5,000 of the planned 7,000 logs were in place. Emergency medical technicians and trained first responders of the Texas A&M Emergency Care Team (TAMECT) rushed to the scene. A student-run volunteer service, who staffed each stage of construction, also began administering first aid to the victims who were thrown clear. TAMECT also alerted the University Police and University EMS, who dispatched all remaining university medics, and requested mutual aid from surrounding agencies. In addition to the mutual aid received from the College Station and Bryan, Texas EMS, Fire, and Police Departments, the members of Texas Task Force 1, the state’s elite emergency response team, were also dispatched to assist the rescue efforts.

As with any disaster, word of the collapse spread among students and the community within minutes. By the time the sun rose, the accident was the subject of news reports around the world, and within hours, 50 news satellite trucks were broadcasting from the Texas A&M campus. Because of the precariousness of the structure, the rescue efforts took over 24 hours to complete. The process was slow, because they didn’t want to risk hurting anyone else, or further injuring the students still trapped inside. Students, including the entire Texas A&M football team and many members of the university’s Corps of Cadets, rushed to the site to assist rescue workers with the manual removal of the logs. To further complicate the rescue efforts, they had to call in the Texas A&M civil engineering department to examine the site and help the workers determine the order in which the logs could be safely removed. Also, at the request of the Texas Forest Service, Steely Lumber Company in Huntsville, Texas, sent log-moving equipment and operators to make removal safer for all concerned. At the time of the accident, there were 58 people, students and former students, working on the stack. Of those 58 people, 12 were killed and 27 were injured. Killed in the initial collapse were ten students and one former student. Another student died in the hospital the next day. The last person pulled out alive was John Comstock, who spent months in the hospital following amputation of his left leg and partial paralysis of his right side. He returned to A&M in 2001 to finish his degree.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, “the university gave the National Forestry Hero Award to an employee of Steely Lumber Company, James Gibson, for rescuing students. By 2000 Texas A&M spent over $80,000 so students and administrators could travel to the funerals of the deceased, including $40,000 so 125 students and staff could attend a funeral in Turlock, California by way of private aircraft; most of the persons on board were students. The total amount of funds spent by the university on all disaster-related expenses by that date was $292,000.” For two years, the university tried to decide on a possible way to reinstate the tradition. A task force was formed, and they proposed a new design. The task force recommended that students be allowed to participate in building the bonfire as long as they were monitored by professional construction experts. That plan wasn’t exactly received with open arms by the students. They felt like it would no longer be a student

project. In the end, it didn’t matter, because the cost of a liability policy to cover these events would cost more than $2 million per year. With that in mind, the bonfires were discontinued in 2002. Bowen’s successor Robert Gates upheld this decision. In recent years, some students have held smaller bonfires off campus, but the school is not involved with these. Multiple memorials were held to remember the victims of the disaster.

project. In the end, it didn’t matter, because the cost of a liability policy to cover these events would cost more than $2 million per year. With that in mind, the bonfires were discontinued in 2002. Bowen’s successor Robert Gates upheld this decision. In recent years, some students have held smaller bonfires off campus, but the school is not involved with these. Multiple memorials were held to remember the victims of the disaster.

Yesterday in Casper, Wyoming, the Burlington Northern San Francisco Railway hosted a very special event. It was a train ride for the area’s first responders and their family’s. What an amazing thing to do for those people who are out there every day, often putting their lives on the line, to save those in need. My brother-in-law, Chris Hadlock is one of those first responders, as is his son-in-law, Jason Sawdon. Chris is a Lieutenant with the Casper Police Department and Jason is a patrolman with the Wyoming Highway Patrol, and I happen to know that they have been the first responders to some pretty awful crash scenes, and I hate to even think of some of the things they have seen. Nevertheless, when they show up at the scene, people feel comforted. Help has arrived, and they are glad.

Yesterday in Casper, Wyoming, the Burlington Northern San Francisco Railway hosted a very special event. It was a train ride for the area’s first responders and their family’s. What an amazing thing to do for those people who are out there every day, often putting their lives on the line, to save those in need. My brother-in-law, Chris Hadlock is one of those first responders, as is his son-in-law, Jason Sawdon. Chris is a Lieutenant with the Casper Police Department and Jason is a patrolman with the Wyoming Highway Patrol, and I happen to know that they have been the first responders to some pretty awful crash scenes, and I hate to even think of some of the things they have seen. Nevertheless, when they show up at the scene, people feel comforted. Help has arrived, and they are glad.

The event, hosted by BNSF Railway, was to honor the police and fire departments in the city. These people the ones we count on to come to the rescue no matter what the situation, and many people would not be here today, were it not for those first responders. The train ride left from Casper, and went out just past the Dave

Johnston Power Plant outside of Glenrock. Chris and Jason were able to bring their family members on the trip, so my sister, Allyn Hadlock; niece, Jessi Sawdon; niece Kellie Hadlock; nephew Ryan Hadlock, his wife Chelsea and their children Ethan and Aurora all got to go along. Allyn told me that the passenger cars were beautiful and comfortable, and they had snacks like hot dogs, chips, and drinks. There was also a souvenier shop, so they all bought BNSF drinking cups. She told me that there were a total of at least 15 cars full of people, and they all had a wonderful time. For my niece Jessi, the trip held a special memory. Her grandpa, my dad, Allen Spencer used to take her out to see the Amtrak trains in Fort Morgan, Colorado, when she lived there as a child. He and her grandma, my mom, Collene Spencer would have loved this for sure.

Johnston Power Plant outside of Glenrock. Chris and Jason were able to bring their family members on the trip, so my sister, Allyn Hadlock; niece, Jessi Sawdon; niece Kellie Hadlock; nephew Ryan Hadlock, his wife Chelsea and their children Ethan and Aurora all got to go along. Allyn told me that the passenger cars were beautiful and comfortable, and they had snacks like hot dogs, chips, and drinks. There was also a souvenier shop, so they all bought BNSF drinking cups. She told me that there were a total of at least 15 cars full of people, and they all had a wonderful time. For my niece Jessi, the trip held a special memory. Her grandpa, my dad, Allen Spencer used to take her out to see the Amtrak trains in Fort Morgan, Colorado, when she lived there as a child. He and her grandma, my mom, Collene Spencer would have loved this for sure.

“BNSF’s First Responder Express is a signature program recognizing the broad service and accomplishments of these very special community contributors.” according to Joe Faust, regional director of public affairs. I think it is an awesome way to honor a group of people who are so often overlooked until we need them that is, and

even then, many people almost look at them in the same way as they would a sales person…like it’s just a job. It really isn’t just a job. These people really care about helping others, and they are willing to put their life on the line to save the life of another person. I think the First Responder Express program is a wonderful thing for BNSF Railway to do, and I personally want to thank all the first responders for their service to their communities. And to our first responders, Chris Hadlock and Jason Sawdon…thank you both for all you do. Your service to this community is an amazing blessing. We love you both!!

even then, many people almost look at them in the same way as they would a sales person…like it’s just a job. It really isn’t just a job. These people really care about helping others, and they are willing to put their life on the line to save the life of another person. I think the First Responder Express program is a wonderful thing for BNSF Railway to do, and I personally want to thank all the first responders for their service to their communities. And to our first responders, Chris Hadlock and Jason Sawdon…thank you both for all you do. Your service to this community is an amazing blessing. We love you both!!