family

My aunt, Deloris “Dee” Johnson was such a sweet person. She was the third child of my grandparents, George and Hattie Byer, and she truly loved her little siblings. She was happy to teach them things, and when she could, she really enjoyed buying things for them. One of the biggest gifts was a piano that graced Grandma Byer’s house for the rest of her life. We all played on that piano, and sometimes I wonder how Grandma kept her sanity. Nevertheless, that piano was a great blessing, and it was Aunt Dee’s great pleasure to gift it to her family. Aunt Dee was really a very special sister to her siblings.

My aunt, Deloris “Dee” Johnson was such a sweet person. She was the third child of my grandparents, George and Hattie Byer, and she truly loved her little siblings. She was happy to teach them things, and when she could, she really enjoyed buying things for them. One of the biggest gifts was a piano that graced Grandma Byer’s house for the rest of her life. We all played on that piano, and sometimes I wonder how Grandma kept her sanity. Nevertheless, that piano was a great blessing, and it was Aunt Dee’s great pleasure to gift it to her family. Aunt Dee was really a very special sister to her siblings.

Aunt Dee had a big imagination. She wanted to see how it felt to be a bird, so she gathered up one of her younger siblings, wrapped up in a trench coat, and stood in the wind. Of course, they didn’t really fly, but it felt like it. I know, because I’ve done that myself. It’s lots of fun. My mom, Collene Spencer, Aunt Dee’s younger sister said that her sister was always inventing something, but Mom didn’t tell me what. I’m sure that over the years everyone forgot what they were, because if they weren’t successful, that would be the end of it. Her son, Elmer did say that his mom was the true inventor of the “shoe watch.” That was an invention she started by attaching a watch to her shoe to help her be on time. It didn’t help Aunt Dee, but then being on time was something that the Byer family was famous for not being.

Aunt Dee grew up in a household of singing. Grandma Byer made housework fun for her nine children with the

“sing while you work” concept. Aunt Dee, like most of her siblings carried that into her adult life. I think they all thought that singing gave them a sunny disposition, and I would have to agree. Having a mom who sings around the house, makes for a lighthearted home. I think that as a child of a song-filled home, my cousins would agree that a singing mom is one of the more pleasant memories of our childhood. Today would have been my Aunt Dee’s 92nd birthday. She has been in Heaven now for 27 years. I find that so hard to believe. Happy birthday in Heaven, Aunt Dee. We love you and still miss you very much.

“sing while you work” concept. Aunt Dee, like most of her siblings carried that into her adult life. I think they all thought that singing gave them a sunny disposition, and I would have to agree. Having a mom who sings around the house, makes for a lighthearted home. I think that as a child of a song-filled home, my cousins would agree that a singing mom is one of the more pleasant memories of our childhood. Today would have been my Aunt Dee’s 92nd birthday. She has been in Heaven now for 27 years. I find that so hard to believe. Happy birthday in Heaven, Aunt Dee. We love you and still miss you very much.

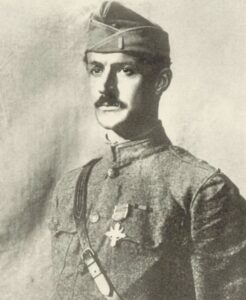

There were amazing pilots on both sides of World War I. One fighter pilot who really stood out as a superstar was Baron von Richthofen, known to the world as the Red Baron. The Red Baron was born on May 2, 1892, into a family of Prussian nobles. Growing up in the Silesia region of what is now Poland, he lived the kind of life you would expect of a nobleman. He passed the time playing sports, riding horses, and hunting wild game, a passion that would follow him for the rest of his life. As was common and on the wishes of his father, Richthofen was enrolled in military school at age 11. Many people felt that military school would provide the best discipline and training, especially if one were going to be an officer. Shortly before his 18th birthday, he was commissioned as an officer in a German cavalry unit.

There were amazing pilots on both sides of World War I. One fighter pilot who really stood out as a superstar was Baron von Richthofen, known to the world as the Red Baron. The Red Baron was born on May 2, 1892, into a family of Prussian nobles. Growing up in the Silesia region of what is now Poland, he lived the kind of life you would expect of a nobleman. He passed the time playing sports, riding horses, and hunting wild game, a passion that would follow him for the rest of his life. As was common and on the wishes of his father, Richthofen was enrolled in military school at age 11. Many people felt that military school would provide the best discipline and training, especially if one were going to be an officer. Shortly before his 18th birthday, he was commissioned as an officer in a German cavalry unit.

Richthofen transferred to the Air Service in 1915, and in 1916 he became one of the first members of fighter squadron Jagdstaffel 2. He was a natural and quickly distinguished himself as a fighter pilot. Then, in 1917 became the leader of Jasta 11. He would go on to lead the larger fighter wing Jagdgeschwader I, which was also known as “The Flying Circus” or “Richthofen’s Circus” mostly because of the bright colors of its aircraft, but maybe because of the way the unit was transferred from one area of Allied air activity to another. When units were moved, it was like a travelling circus. They moved and often set up in tents on improvised airfields.

Between September 1916 and April 1918, he shot down 80 enemy aircraft. That was more than any other pilot during World War I. The Red Baron once wrote, “I never get into an aircraft for fun. I aim first for the head of the pilot, or rather at the head of the observer, if there is one.” He was well known for his crimson-painted Albatros biplanes and Fokker triplanes, and the “Red Baron” by 1918, Richthofen was regarded as a national hero in Germany, and strangely, Richthofen was even respected by his enemies, which is very rare indeed.

Loyal to the end, Richthofen received a fatal wound while flying over Morlancourt Ridge near the Somme River, just after 11:00am on April 21, 1918. He had been pursuing, a Sopwith Camel piloted by Canadian novice Wilfrid Reid “Wop” May of the Number 209 Squadron, Royal Air Force. May had just fired on the Red Baron’s cousin, Lieutenant Wolfram von Richthofen. When he saw his cousin being attacked, the Red Baron flew rescue him. He fired on May’s plane, causing him to pull away, then he chased May across the Somme. The Baron was spotted and briefly attacked by a Camel piloted by May’s school friend and flight commander, Canadian Captain Arthur “Roy” Brown. Brown had to dive steeply at very high speed to intervene, and then had to climb steeply to avoid hitting the ground. Richthofen turned to avoid this attack, and then resumed his pursuit of May.

During this final stage in his pursuit of May, Richthofen was hit by a single .303 bullet through the chest, severely damaging his heart and lungs. He would have bled out in less than a minute. Now pilotless, the plane stalled and went into a steep dive. It hit the ground in a field on a hill near the Bray-Corbie Road, just north of the village of Vaux-sur-Somme. This was in a sector defended by the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). The plane bounced heavily when it hit the ground, and the undercarriage collapsed. The fuel tank was smashed before the aircraft skidded to a stop. Several witnesses, including Gunner George Ridgway, reached the crashed plane and found Richthofen already dead, and his face slammed into the butts of his machine guns, breaking his nose, fracturing his jaw and creating contusions on his face.

Number 3 Squadron AFC’s commanding officer Major David Blake, who was responsible for Richthofen’s body, regarded the Red Baron with great respect. It was Blake who was responsible for organizing the funeral, and he decided on a full military funeral. Richthofen’s body was buried in the cemetery at the village of Bertangles, near Amiens, on April 22, 1918. Six of Number 3 Squadron’s officers served as pallbearers, and a guard of honor from the squadron’s other ranks fired a salute. Allied squadrons stationed nearby presented memorial

wreaths, one of which was inscribed with the words, “To Our Gallant and Worthy Foe.” It was an extremely respectful way to care for the body of the enemy, and for that, I have much respect for the Number 3 Squadron. Even though this man was the enemy, they knew he was just doing his job, as they would do theirs. It wasn’t personal, it was just war. In 1975 the body was moved to a Richthofen family grave plot at the Südfriedhof in Wiesbaden.

wreaths, one of which was inscribed with the words, “To Our Gallant and Worthy Foe.” It was an extremely respectful way to care for the body of the enemy, and for that, I have much respect for the Number 3 Squadron. Even though this man was the enemy, they knew he was just doing his job, as they would do theirs. It wasn’t personal, it was just war. In 1975 the body was moved to a Richthofen family grave plot at the Südfriedhof in Wiesbaden.

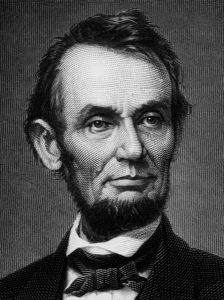

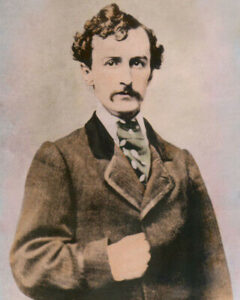

John Wilkes Booth was an actor, and as such, he had an expectation of applause following a performance. That is just what he thought the assassination of President Lincoln was. No, he didn’t think it was fake. He knew he was murdering the President of the United States, but he somehow thought people would consider it one of his greatest performances…the crowning moment of his stage career. It never occurred to him that the people who had loved him as an actor would suddenly turn against him.

John Wilkes Booth was an actor, and as such, he had an expectation of applause following a performance. That is just what he thought the assassination of President Lincoln was. No, he didn’t think it was fake. He knew he was murdering the President of the United States, but he somehow thought people would consider it one of his greatest performances…the crowning moment of his stage career. It never occurred to him that the people who had loved him as an actor would suddenly turn against him.

At the very least, he expected to be greeted with applause and support by those sympathetic to the Confederacy. Instead, he found, much to his shock and great dismay, that he was a hounded man, and few wanted to associate with him. Oh, the loyalists to the Confederacy did their duty by him, but with great reluctance. He first encountered this reaction when he and David Herold, who was an American pharmacist’s assistant and Wilkes accomplice in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, stumbled upon a man in the dark, while searching for the home of Colonel Cox. The man, a local named Oswell Swann, reluctantly agreed to guide then to the Cox home, but only if he received payment for his services. He considered it just reward for the risk he was taking. Afterward, Swann collected his fee and vanished into the night, leaving the fugitives to the “hospitality” of Colonel Cox. That “hospitality” consisted of a few supplies, including whiskey, and a servant to lead the men to a hiding place in the woods. Cox certainly didn’t want these men to be found in his house.

Cox informed Booth that he was to “remain hidden in the woods until contacted.” Then Cox sent for Thomas Jones, a Confederate agent with experience in smuggling spies and information across the Potomac River into Virginia. Jones agreed to get them out and guide them across the Potomac, for a fee, but when he visited the fugitives in the woods, where they hid in a pine thicket, he told them it would be several days before he could do so. The manhunt for Booth and Herold was massive. Federal troops combed the area, searching properties and interrogating citizens over whether they had seen two men traveling together. Booth was very distressed, because instead of receiving the expected support and appreciation of the south, Booth found himself confined to a pine thicket!! Jones provided the men with newspapers, from which Booth discovered that he was widely considered a villainous murderer, rather than the Confederate hero he had expected to be. He wrote about his “horrible” fate, and the “injustice” of it all, in a diary he kept in an appointment book.

Federal authorities had most of the conspirators who had planned to kidnap Abraham Lincoln in custody by April 20, 1865. Several were not party to the assassination, but because they were involved in the kidnapping plans, they were held anyway. Three men were still not in custody…Booth, Herold, and John Surratt remained at large. The War Department put out wanted poster, released in Washington on April 20, offering a $50,000 reward for Booth, and $25,000 apiece for Herold and Surratt. By then, Surratt was hiding out in Canada, even though he knew that his mother was being held in federal custody. Coward that he was, Surratt was making plans to flee to Europe. Booth and Herold continued to cower in a pine thicket, relatively helpless. They didn’t dare leave, because they would be seen and immediately arrested. A dejected Booth spent his time drinking whiskey and scribbling in his makeshift diary over the unfairness of his reception. He believed his action had made him a martyr to the Confederate cause.

When the fugitives finally attempted to cross the Potomac, on about April 21, Jones’s guidance consisted of verbal instructions directing them to a waiting boat. These men had no boating experience, and the night was windy. The tides and swift current didn’t help matters either. Nor did the gunboats in the area. Booth whined into his diary, “last night being chased by gunboats till I was forced to return wet, cold, and starving.” Needless to say, the crossing was a failure, but Booth’s overly dramatic entry exaggerated what may have been an encounter with USS Juniper, positioned in the river near their point of crossing. Juniper’s log did not include a report of chasing anything that night. Booth likely spotted the gunboat, and in a panic, returned to the Maryland shore. Booth’s fugitive days ended when he was caught on April 26, 1865, near Port Royal, Virginia. As Booth and his co-conspirator, David Herold, cowered inside a barn, the soldiers demanded that they surrender. John Wilkes Booth died in agonizing fashion at the hands of Union soldiers in Port Royal, Virginia,

two weeks after he assassinated Abraham Lincoln. When the Union soldiers demanded their surrender, Herold complied. But Booth refused. He didn’t leave the barn until one of the soldiers set it on fire. As he tried to sneak out in the shadows and flame, a shot cracked through the silent night…and found its mark. Booth briefly held on to life, but in the end, the bullet would be his demise…in true disgraced style.

two weeks after he assassinated Abraham Lincoln. When the Union soldiers demanded their surrender, Herold complied. But Booth refused. He didn’t leave the barn until one of the soldiers set it on fire. As he tried to sneak out in the shadows and flame, a shot cracked through the silent night…and found its mark. Booth briefly held on to life, but in the end, the bullet would be his demise…in true disgraced style.

We all think of our first president as being a patriot hero of the Revolutionary War, leading to the independence of our nation and the many freedoms we now enjoy, and he was, but he was other things before he was all that. Everyone is other things before they become the thing they were destined to become. George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, at Popes Creek in Westmoreland County, in the British colony of Virginia. He was the first of six children of Augustine and Mary Ball Washington. His father was a justice of the peace and a prominent public figure who had four additional children from his first marriage to Jane Butler. He did come from a prominent family, and that could have afforded him much, but that wouldn’t have been his style.

We all think of our first president as being a patriot hero of the Revolutionary War, leading to the independence of our nation and the many freedoms we now enjoy, and he was, but he was other things before he was all that. Everyone is other things before they become the thing they were destined to become. George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, at Popes Creek in Westmoreland County, in the British colony of Virginia. He was the first of six children of Augustine and Mary Ball Washington. His father was a justice of the peace and a prominent public figure who had four additional children from his first marriage to Jane Butler. He did come from a prominent family, and that could have afforded him much, but that wouldn’t have been his style.

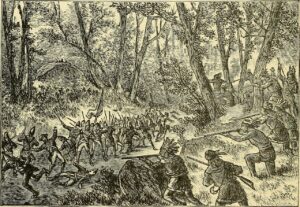

It is well known that George Washington led the Continental Army to victory against Great Britain in the 1770s and early 1780s, but a few decades earlier, like most young adults, George had a different view of things, and he actually fought for the British Empire. In 1754, 22-year-old Washington, then a lieutenant colonel for the British, managed to actually start a war with his actions. It is said that young Washington led his regiment into a skirmish with French troops, and the action escalated into the French and Indian War. One eyewitness totally blamed Washington, saying, “Colonel Washington begun himself and fired and then his people.” It was “a shot heard ’round the world,” sparking an epic, imperial struggle between Great Britain and France.

In reality, it wasn’t Washington’s fault. Tensions between France and Great Britain had been brewing in North America for more than a century. America had a lot of land, and with that would come a lot of power. The British and the French had been fighting over that land and that power. Swept up in the struggle were the inhabitants of New France, the British colonists, the Native Americans, and regular troops from France and Britain. What George Washington did that day really had little to do with a battle that was coming no matter

what. Had he not attacked, the war would just have started days or weeks down the road, but it would have started, nevertheless. The British and the French saw the vast lands of what would become the United States of America as a way to expand their power in the world, and like most wars, the land disputes brought with them an explosion that really could be heard around the world. What Washington did was a small battle in a much bigger war. And what he did later, changed history forever.

what. Had he not attacked, the war would just have started days or weeks down the road, but it would have started, nevertheless. The British and the French saw the vast lands of what would become the United States of America as a way to expand their power in the world, and like most wars, the land disputes brought with them an explosion that really could be heard around the world. What Washington did was a small battle in a much bigger war. And what he did later, changed history forever.

On April 18, 1906, many of the people in the San Francisco, California area were sound asleep in their beds. It was, after all, 5:13am. Suddenly, the people were jolted awake by an earthquake, which was estimated to be close to 8.0 on the Richter scale. When the quake struck San Francisco, California, it toppled numerous buildings. The cause of the quake was a slip of the San Andreas Fault over a segment about 275 miles long. The resulting shock waves could be felt from southern Oregon down to Los Angeles.

On April 18, 1906, many of the people in the San Francisco, California area were sound asleep in their beds. It was, after all, 5:13am. Suddenly, the people were jolted awake by an earthquake, which was estimated to be close to 8.0 on the Richter scale. When the quake struck San Francisco, California, it toppled numerous buildings. The cause of the quake was a slip of the San Andreas Fault over a segment about 275 miles long. The resulting shock waves could be felt from southern Oregon down to Los Angeles.

At that time, San Francisco’s had a variety of brick buildings and wooden Victorian structures that were not really earthquake reinforced. Nobody knew about making buildings strong enough to resist destruction from an earthquake. It was one of the things we would learn from the results of a disaster. It seems that with each disaster, we learn how to prevent the loss of so many buildings and lives. The old buildings were devastated. Along with the collapsed buildings, came devastating fires, and because many of the water mains had broken, firefighters were prevented from stopping  the fires. Firestorms soon developed citywide. US Army troops from Fort Mason reported to the Hall of Justice around 7am, and San Francisco Mayor E.E. Schmitz set a dusk-to-dawn curfew and authorized soldiers to shoot to kill anyone found looting. Disasters like these always seem to bring out the worst in people, even those who might not have done such things under normal circumstances.

the fires. Firestorms soon developed citywide. US Army troops from Fort Mason reported to the Hall of Justice around 7am, and San Francisco Mayor E.E. Schmitz set a dusk-to-dawn curfew and authorized soldiers to shoot to kill anyone found looting. Disasters like these always seem to bring out the worst in people, even those who might not have done such things under normal circumstances.

As significant aftershocks continued, firefighters and US troops fought desperately to control the ongoing fires. Sadly, that sometimes meant dynamiting whole city blocks to create firewalls. Many people were trapped where they were, because the fires prevented their escape, even though they were not stuck in a collapsed building. Finally, on April 20th, several thousands of refugees were evacuated from the foot of Van Ness Avenue. The army would eventually house 20,000 refugees in more than 20 military-style tent camps across the city. The people had no idea how long they might have to be there.

Most of the fires were extinguished by April 23rd, and the authorities started the task of rebuilding the devastated city. In all, approximately 3,000 people lost their lives as a result of the Great San Francisco Earthquake and the devastating fires it inflicted upon the city. Almost 30,000 buildings were destroyed, including most of the city’s homes and nearly all the central business district. The rebuilding would take a long time, and the new structures were reinforced to be able to better withstand the shaking of the San Andreas fault. This quake may not have been the “Big One” that is predicted, but at an estimated 7.9 or 8.0, it was right up there.

My sister-in-law, Jennifer Parmely’s partner, Brian Cratty is a mountain man…seriously. He loves being on Casper Mountain, Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter. In the Summer, Brian hikes and mountain bikes for much of the day. He is totally in his element when he is on the mountain. Brian and Jennifer own a cabin on the mountain, and Brian, who is retired, spends as much time as possible there. I’m sure Jennifer will spend more time there as well, now that she has retired too.

My sister-in-law, Jennifer Parmely’s partner, Brian Cratty is a mountain man…seriously. He loves being on Casper Mountain, Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter. In the Summer, Brian hikes and mountain bikes for much of the day. He is totally in his element when he is on the mountain. Brian and Jennifer own a cabin on the mountain, and Brian, who is retired, spends as much time as possible there. I’m sure Jennifer will spend more time there as well, now that she has retired too.

Even in the Winter, Brian spends most days at the cabin. When he gets there, he builds a fire in the cabin and then gets to work keeping it shoveled out. The deep accumulations of snow can do so much damage to a cabin that is not kept dug out. A structure can only hold so much snow before damage becomes inevitable. Normally there is a good amount of snow on the mountain, but this winter has been a real challenge. Nevertheless, Brian as worked hard, persevered, and kept it at bay, protecting the cabin. I think we have all been shocked ah the amount of snow on the mountain, and this last

storm dumped an additional 48+ inches on the mountain. It looks to me like we might have as much as 10 feet in some places.

storm dumped an additional 48+ inches on the mountain. It looks to me like we might have as much as 10 feet in some places.

Driving to the cabin in the Winter is not possible, so they ski into the cabin in the Winter. Jennifer tells me that it only takes about 35 minutes from the Nordic lodge to get there. They love cross-country skiing, so for them it’s not a burden, but rather an adventure. The mountain might be teeming with activity in the Summer, but the Winter presents a very different atmosphere. There is a deep quiet a lot of the time, and that is part of its charm. Of course, the cabin is near trails too, and there might be snowmobilers around too, but not all the time, so the quiet is the bulk of the day.

Some days, Brian is just not able to get up to the mountain, so on those dreaded “stuck at home” days, Brian

likes to work on puzzles. Not everyone has that patience to put puzzles together, but Brian really enjoys it. He also loves to cook, and that is always an advantage for Jennifer, who reaps the benefits of his skill, and he enjoys watching movies, although he probably finds it hard to sit there when he would rather be on the mountain shoveling snow!! Today is Brian’s birthday. Happy birthday Brian!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

likes to work on puzzles. Not everyone has that patience to put puzzles together, but Brian really enjoys it. He also loves to cook, and that is always an advantage for Jennifer, who reaps the benefits of his skill, and he enjoys watching movies, although he probably finds it hard to sit there when he would rather be on the mountain shoveling snow!! Today is Brian’s birthday. Happy birthday Brian!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

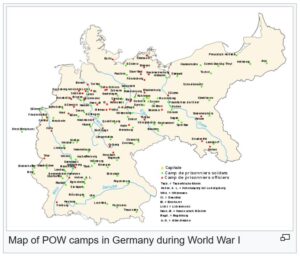

World War I was a different era, even in the way war was conducted. Oh, war is still war, and there is wounding, bombing, killing, and capturing. Nevertheless, with one leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II, there was also compassion. After being captured and placed in a POW camp, a British officer, Captain Robert Campbell found out that his mother was dying. He couldn’t bear the thought of not seeing his mother before she passed away, and in his grief, he took a chance. He appealed to Kaiser Wilhelm II, asking to be allowed to go home to visit his mother before she died. Amazingly, Kaiser Wilhelm II granted his request, on the condition that he return to the POW camp after the visit.

World War I was a different era, even in the way war was conducted. Oh, war is still war, and there is wounding, bombing, killing, and capturing. Nevertheless, with one leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II, there was also compassion. After being captured and placed in a POW camp, a British officer, Captain Robert Campbell found out that his mother was dying. He couldn’t bear the thought of not seeing his mother before she passed away, and in his grief, he took a chance. He appealed to Kaiser Wilhelm II, asking to be allowed to go home to visit his mother before she died. Amazingly, Kaiser Wilhelm II granted his request, on the condition that he return to the POW camp after the visit.

When you think about it, once he was safely home with his mother, Captain Campbell could have simply stayed. Seriously, what could the Kaiser have done about it. Nevertheless, being an honorable man, Captain Campbell kept his promise to Kaiser Wilhelm II and returned from Kent to Germany after visiting his mother for a week. He stayed at the camp until the war ended in 1918. That was not the end of the story, however.

On August 24, 1914, then 29-year-old Captain Campbell, of the 1st Battalion East Surrey Regiment, was captured in northern France. He was sent to a prisoner-of-war (POW) camp in Magdeburg, north-east Germany. It was there that he received the heartbreaking news that his mother, Louise was dying of cancer. Captain Campbell traveled through the Netherlands and then by boat and train to Gravesend in Kent, where he spent a week with his mother before returning to Germany the same way. His mother died in February 1917.

With the kindness of the Kaiser, and a duty to honor his word, Captain Campbell, knowing that if he didn’t return, no one else would ever be given that same consideration, Captain Campbell returned to Germany. Strangely, there was no issues during his return. I suppose the Kaiser could have cleared the way previously, but it would be my guess that the Kaiser was just as shocked by the return as I am. Unfortunately, Britain wasn’t as considerate, because they blocked a similar request from German prisoner Peter Gastreich, who was being held at an internment camp on the Isle of Man. After that no other British prisoners of war were afforded compassionate leave.

As for Captain Campbell, while he felt duty-bound to return to captivity, he did not feel duty-bound to stay in

captivity. As soon as Captain Campbell returned to the camp, he set about trying to escape. He and a group of other prisoners spent nine months digging their way out of the camp before being captured on the Dutch border and sent back. He remained in the camp until 1918 and served in the military until 1925. Captain Campbell rejoined the military when World War II broke out in 1939 and served as the chief observer of the Royal Observer Corps on the Isle of Wight. He died in the Isle of Wight in July 1966, aged 81.

captivity. As soon as Captain Campbell returned to the camp, he set about trying to escape. He and a group of other prisoners spent nine months digging their way out of the camp before being captured on the Dutch border and sent back. He remained in the camp until 1918 and served in the military until 1925. Captain Campbell rejoined the military when World War II broke out in 1939 and served as the chief observer of the Royal Observer Corps on the Isle of Wight. He died in the Isle of Wight in July 1966, aged 81.

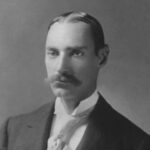

John Jacob Astor IV was born on July 13, 1864 at his parents’ country estate of Ferncliff in Rhinebeck, New York. He was the youngest of five children and only son of William Backhouse Astor Jr, a businessman, collector, and racehorse breeder/owner, and Caroline Webster “Lina” Schermerhorn, a Dutch-American socialite. His four elder sisters were Emily, Helen, Charlotte, and Caroline (“Carrie”). John Astor IV was an American business magnate, real estate developer, investor, writer, lieutenant colonel in the Spanish–American War. He came from a long line of the very prominent Astor family.

John Jacob Astor IV was born on July 13, 1864 at his parents’ country estate of Ferncliff in Rhinebeck, New York. He was the youngest of five children and only son of William Backhouse Astor Jr, a businessman, collector, and racehorse breeder/owner, and Caroline Webster “Lina” Schermerhorn, a Dutch-American socialite. His four elder sisters were Emily, Helen, Charlotte, and Caroline (“Carrie”). John Astor IV was an American business magnate, real estate developer, investor, writer, lieutenant colonel in the Spanish–American War. He came from a long line of the very prominent Astor family.

Astor’s was an accomplished writer, having published “A Journey in Other Worlds” (1894), a science-fiction novel about life in the year 2000 on the planets Saturn and Jupiter. He was also an inventor. He patented several inventions, including a bicycle brake in 1898, a “vibratory disintegrator” used to produce gas from peat moss, and a pneumatic road-improver, and he helped develop a turbine engine. He was a great visionary, and his contributions to the world were amazing.

Astor married socialite Ava Lowle Willing on February 17, 1891. The couple had two children, William Vincent Astor (November 15, 1891 – February 3, 1959), businessman and philanthropist, and Ava Alice Muriel Astor (July 7, 1902 – July 19, 1956). The couple divorced in November 1909. Astor IV remarried shortly thereafter, compounding the scandal of his divorce. At the age of 47, Astor married 18-year-old socialite Madeleine Talmage Force, the sister of real estate businesswoman and socialite Katherine Emmons Force. Astor and Force were married in his mother’s ballroom at Beechwood, the family’s Newport, Rhode Island, mansion. There was also much controversy over their 29-year age difference. His son Vincent despised Force, yet he served as best man at his father’s wedding. The couple took an extended honeymoon in Europe and Egypt to wait for the gossip to calm down. Among the few Americans who did not spurn him at this time was Margaret Brown, later fictionalized as The Unsinkable Molly Brown. She accompanied the Astors to Egypt and France. After receiving a call to return to the United States, Brown accompanied the couple back home aboard RMS Titanic.

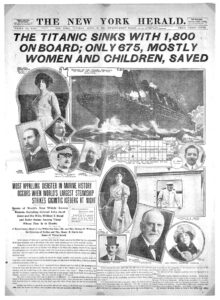

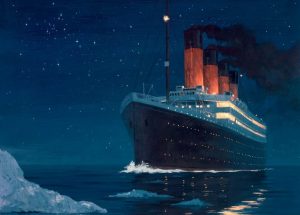

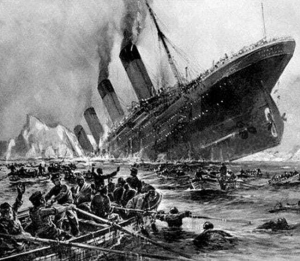

Astor IV died in the sinking of the RMS Titanic during the early hours of April 15, 1912. Astor was the richest passenger aboard the RMS Titanic and was thought to be among the richest people in the world at that time. He was also a true gentleman, who would never have been on a lifeboat without knowing that all the women and children were on lifeboats. Astor IV had a net worth of roughly $87 million when he died, which would be

equivalent to $2.44 billion in 2021. Astor, like his predecessors also made millions in real estate. In 1897, Astor built the Astoria Hotel, “the world’s most luxurious hotel”, in New York City, adjoining the Waldorf Hotel owned by Astor’s cousin and rival, William. Later, the complex became known as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The Waldorf-Astoria was the host location to the United States inquiries into the sinking of the RMS Titanic, on which Astor died.

equivalent to $2.44 billion in 2021. Astor, like his predecessors also made millions in real estate. In 1897, Astor built the Astoria Hotel, “the world’s most luxurious hotel”, in New York City, adjoining the Waldorf Hotel owned by Astor’s cousin and rival, William. Later, the complex became known as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The Waldorf-Astoria was the host location to the United States inquiries into the sinking of the RMS Titanic, on which Astor died.

When we are going through things that others have gone through, it can be extremely helpful to listen to what they know. That advise is important for everyone, everywhere, because if we don’t listen and heed those warnings, we might just find ourselves learning a very hard lesson…that hindsight is always 20/20.

When we are going through things that others have gone through, it can be extremely helpful to listen to what they know. That advise is important for everyone, everywhere, because if we don’t listen and heed those warnings, we might just find ourselves learning a very hard lesson…that hindsight is always 20/20.

On April 14th, 1912, SS Mesaba, a ship on the same route as RMS Titanic had traveled through waters with dangerous icebergs floating around just a few hours before Titanic was to be there. The Mesaba sent out a warning about icebergs to every ship in the area, including  the Titanic. The message went out, and the crew of the Titanic received it, but the radio operator who received the message didn’t think it was important enough to deliver to the captain. This was probably because the Titanic’s radiomen were very busy. The passengers were sending and receiving messages with the mainland. It was a show of prestige. Even with the busy day, one would think that a message about an unusually high number of icebergs would have gone into the “high priority” pile, but of course hindsight is always 20/20. I’m sure that if John George Phillips, the Titanic’s senior wireless operator, had known then what he soon would know, he would have rushed the message to the captain immediately.

the Titanic. The message went out, and the crew of the Titanic received it, but the radio operator who received the message didn’t think it was important enough to deliver to the captain. This was probably because the Titanic’s radiomen were very busy. The passengers were sending and receiving messages with the mainland. It was a show of prestige. Even with the busy day, one would think that a message about an unusually high number of icebergs would have gone into the “high priority” pile, but of course hindsight is always 20/20. I’m sure that if John George Phillips, the Titanic’s senior wireless operator, had known then what he soon would know, he would have rushed the message to the captain immediately.

So many things would likely have been different, if people had only known what the future would bring. People wouldn’t have even been on the Titanic had they known. Then again, if the crew had known that an iceberg could do so much damage to an “unsinkable” ship, they would have listened when they were warned of very serious danger lurking in the waters ahead of them. They would have been crawling through the area, or they would have stopped for the night. They certainly wouldn’t have been pushing the ship to near maximum speed in an area of ocean that was filled with icebergs as dangerous as a floating mine or a torpedo. Unfortunately, hindsight is always 20/20, and the only reason we know the dangers now, is that the ship is at the bottom of

the ocean, having succumbed to the very fate everyone was so sure could never happen to the great Titanic.

the ocean, having succumbed to the very fate everyone was so sure could never happen to the great Titanic.

We can’t always know the dangers that lie ahead of us, but it is a wise man that pays attention to warnings of danger so that appropriate action can be taken. We can live with the saying, hindsight is always 20/20, or we can do our very best not to have to see that 20/20 hindsight with great regret.

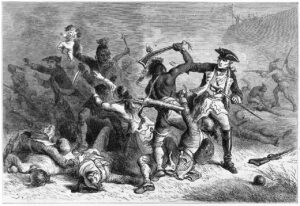

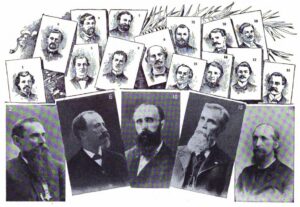

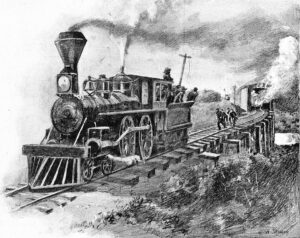

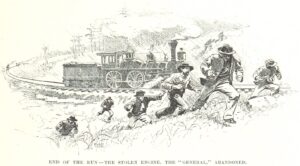

During the Civil War, things like supply lines and lines of communication were crucial to both sides. The railroads became an important asset, as well as a liability, to both sides, depending on what they were carrying and where it was headed. On April 12, 1862, volunteers from the Union Army, led by civilian scout James J Andrews, commandeered a train called The General, and took it northward from Georgia toward Chattanooga, Tennessee. En route, they did as much damage as possible to the vital Western and Atlantic Railroad (W and A) line from Atlanta to Chattanooga. They were pursued for 87 miles by Confederate forces, trying at first to keep up on foot, and later resorting to a succession of locomotives, including The Texas.

During the Civil War, things like supply lines and lines of communication were crucial to both sides. The railroads became an important asset, as well as a liability, to both sides, depending on what they were carrying and where it was headed. On April 12, 1862, volunteers from the Union Army, led by civilian scout James J Andrews, commandeered a train called The General, and took it northward from Georgia toward Chattanooga, Tennessee. En route, they did as much damage as possible to the vital Western and Atlantic Railroad (W and A) line from Atlanta to Chattanooga. They were pursued for 87 miles by Confederate forces, trying at first to keep up on foot, and later resorting to a succession of locomotives, including The Texas.

Known as The Great Locomotive Chase, the military raid was also called the Andrews’ Raid or Mitchel Raid (after Major General Ormsby Mitchel, who had earlier assisted in the capture of Nashville and accepted the surrender of the city). In the end, as often happens in escapades like this, the raid made sensational headlines in newspapers, but it really had little impact on the war. It didn’t stop supply lines for the South or start new ones for the North.

In February, the Union soldiers captured Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, and Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston knew he had to withdraw his forces from central Tennessee to reorganize. Johnston evacuated Nashville on February 23rd, and Nashville became the first Confederate state capital to fall to the Union. For Major General Don Carlos Buell, the taking of Nashville was enough, and on March 11th, Buell’s army was merged into the new Department of the Mississippi under General Henry Halleck. It was then that James J Andrews, a Kentucky-born civilian serving as a secret agent and scout in Tennessee approached Buell with a plan to take eight men to steal a train in Georgia and drive it north. Buell authorized the expedition in August 1863. Andrews, a train engineer in Atlanta, was willing to defect to the Union with his train, and without Andrews, taking over the train would have proved difficult. Getting onboard would have been easy enough, but running the train without experienced personnel is next to impossible. Since Andrews was willing to defect, he might also be able to supply a volunteer train crew to assist in running the train, tearing up track, and burning  bridges, so they would have an even greater chance of succeeding. The main target of the operation was the railway bridge at Bridgeport, Alabama, but Andrews had several other bridges in Georgia and Tennessee in mind too. Some of the men from Major General Mitchel’s division, encamped at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, were tapped to be the volunteers for this first raid.

bridges, so they would have an even greater chance of succeeding. The main target of the operation was the railway bridge at Bridgeport, Alabama, but Andrews had several other bridges in Georgia and Tennessee in mind too. Some of the men from Major General Mitchel’s division, encamped at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, were tapped to be the volunteers for this first raid.

The group of raiders moved south forty miles on foot to the Confederate railhead at Tullahoma. Then the caught a train to Marietta, Georgia. It was then that the operation hit its first snag, when Andrews discovered the engineer had been pressed into service elsewhere. Upon inquiring if any of the raiders knew how to operate a locomotive, they found that none did, and the raid was called off. Two raiders were also confronted by Confederate soldiers while trying to cut the telegraph lines, but successfully pretended to be overworked wiremen. Then the raiders returned north to Union lines, arriving about a week after they had departed. Andrews spent several days rearranging the operation and conducting reconnaissance on the Western and Atlantic Railroad before he headed north to federal lines too. The original raiders all refused to volunteer for the second raid, fearing the enemy. One said that “he felt all the time he was in the enemy’s country as though he had a rope around his neck.”

While the first raid was a bust, the second raid went off pretty well. The General was taken while the crew was a breakfast at the Lacey Hotel in Atlanta, and despite all the efforts to catch them, it arrived at milepost 116.3, north of Ringgold, Georgia, just 18 miles from Chattanooga and out of fuel. Andrews’s men abandoned The General and scattered. Andrews and all of his men were caught within two weeks. They even caught two volunteers who had the hijacking. Mitchel’s attack on Chattanooga was a failure.

All of the raiders were charged with “acts of unlawful belligerency.” The civilians among them were charged as unlawful combatants and spies. They were tried in military courts or courts-martial. Andrews was tried in

Chattanooga, found guilty, and hanged on June 7 in Atlanta. Seven others were transported to Knoxville and convicted as spies. They were returned to Atlanta and were hanged too. Their bodies were buried unceremoniously in an unmarked grave. Those bodies were later reburied in Chattanooga National Cemetery.

Chattanooga, found guilty, and hanged on June 7 in Atlanta. Seven others were transported to Knoxville and convicted as spies. They were returned to Atlanta and were hanged too. Their bodies were buried unceremoniously in an unmarked grave. Those bodies were later reburied in Chattanooga National Cemetery.