factory

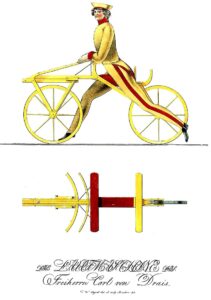

Pierre Lallement was living in Nancy, France when he saw someone on a Dandy Horse, which is basically a strider bike. That bike is powered when the rider runs while straddling a bicycle seat. It’s a great was to teach a child how to balance on a bicycle before they are quite ready for a full two-wheeler. Lallement thought this was very cool, but as a mechanic, he thought he could vastly improve on that design.

Pierre Lallement was living in Nancy, France when he saw someone on a Dandy Horse, which is basically a strider bike. That bike is powered when the rider runs while straddling a bicycle seat. It’s a great was to teach a child how to balance on a bicycle before they are quite ready for a full two-wheeler. Lallement thought this was very cool, but as a mechanic, he thought he could vastly improve on that design.

While living in Nancy and working as a carriage builder, Lallement first encountered a dandy horse. He began to picture a similar device, but with some specific improvements. His ideas made his invention quite different that the dandy horse. Lallement added a transmission and pedals, which allowed for a more efficient, faster, and definitely a more dignified mode of transportation. Lallement began working with Pierre Marchaux, a fellow carriage maker, to fine tune his idea, but it is Lallement who is credited with developing the first functional bicycle prototype. Then, due to a dispute involving himself,  Marchaux and his son, and the Olivier brothers—who later became Marchaux’s partners, Lallement found himself ostracized from the nascent bicycle industry in France.

Marchaux and his son, and the Olivier brothers—who later became Marchaux’s partners, Lallement found himself ostracized from the nascent bicycle industry in France.

Undeterred, Lallement continued his work. In 1865, he immigrated to America with his plans and parts for the invention that existed only in his head at that time. Upon arriving in the United States, Lallement settled in Ansonia, Connecticut. He demonstrated his invention to the locals, with one reportedly fleeing in terror at the sight of a “devil on wheels.” Lallement eventually found an investor, James Carroll, who supported his projects. On November 20, 1866, Lallement applied for and received the first U.S. patent for a pedal-driven bicycle. It must have felt like a amazing achievement for the man who came up with the idea and then was cheated out of the acknowledgement for its invention. While Lallement built and patented the first bicycle in the country, he was once again cheated, not by a person, but rather by circumstances. As a result, he gained little reward or

acknowledgment for introducing an invention that would quickly become widespread.

acknowledgment for introducing an invention that would quickly become widespread.

This time when he was cheated, it was due to insufficient funds to build a factory. For that reason, he sold his patent rights in 1868 and went back to France. There, the bicycle, popularized by Michaux, sparked a “bicycle craze” that swept through Europe. Albert Pope, who obtained the patent in 1876, amassed a fortune from producing the Columbia bicycle and became a prominent cycling proponent, establishing the League of American Wheelmen in 1880. Regrettably, Lallement died unrecognized in Boston in 1881, and only a century later did historians acknowledge his crucial role in the invention of the bicycle.

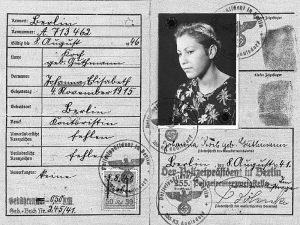

Born Jewish, on April 4, 1922, in Berlin, Germany, did not necessarily set Marie Jalowicz up for a long carefree life. Marie was 11 years old when the Nazi Party came to power, and soon after began to imprison her family members. By age 20, Marie was forced to fend for herself. She found herself faced with the difficult task of constantly avoiding the Nazis. For Marie, this meant somehow assimilating into German life…basically pretending to be a non-Jew. I can’t imagine having to pretend to be a nationality other than my own, but that is what she had to do. Anything about her that was Jewish had to be set aside, forgotten, or hidden from the eyes and ears of the Nazis, who seemed to be everywhere around her.

Born Jewish, on April 4, 1922, in Berlin, Germany, did not necessarily set Marie Jalowicz up for a long carefree life. Marie was 11 years old when the Nazi Party came to power, and soon after began to imprison her family members. By age 20, Marie was forced to fend for herself. She found herself faced with the difficult task of constantly avoiding the Nazis. For Marie, this meant somehow assimilating into German life…basically pretending to be a non-Jew. I can’t imagine having to pretend to be a nationality other than my own, but that is what she had to do. Anything about her that was Jewish had to be set aside, forgotten, or hidden from the eyes and ears of the Nazis, who seemed to be everywhere around her.

Marie knew that as the situation for Jews in Nazi Germany deteriorated, things would grow steadily worse for her. She had to somehow come up with a way to virtually hide in plain sight. When a postman wrongly delivered a letter for a job offer intended for the neighbor in 1941, she told a postman that her “neighbor” Marie was taken by the Nazis, then she simply started walking around without a star on her jacket. She was successfully living under a false identity. She took the job and began  working at the Siemens arms factory in her neighbor’s place. While living this double life, Jalowicz sabotaged production at the arms factory where she worked. Marie evaded Nazi capture through a long string of forgeries, impersonations, and help from people from every walk of life. Marie became Johanna Koch, using her wit and charm to seduce people in positions that could help her and moved around constantly. She took the words of a friend of hers to heart, “In absurd times, everything is absurd. You can save yourselves only by absurd means since the Nazis are out to murder us all.” On more than one occasion she tried to flee Germany, narrowly evading apprehension and escaping back to her homeland each time. She relocated often, and at one point was sold to an abusive Nazi with late-stage syphilis for 15 marks, which added to her cover as a non-Jew. In the coming years, she took menial jobs and lived in several Berlin flats, at times with roommates who were fervent Nazis. I can’t imagine how awful it was for her.

working at the Siemens arms factory in her neighbor’s place. While living this double life, Jalowicz sabotaged production at the arms factory where she worked. Marie evaded Nazi capture through a long string of forgeries, impersonations, and help from people from every walk of life. Marie became Johanna Koch, using her wit and charm to seduce people in positions that could help her and moved around constantly. She took the words of a friend of hers to heart, “In absurd times, everything is absurd. You can save yourselves only by absurd means since the Nazis are out to murder us all.” On more than one occasion she tried to flee Germany, narrowly evading apprehension and escaping back to her homeland each time. She relocated often, and at one point was sold to an abusive Nazi with late-stage syphilis for 15 marks, which added to her cover as a non-Jew. In the coming years, she took menial jobs and lived in several Berlin flats, at times with roommates who were fervent Nazis. I can’t imagine how awful it was for her.

Marie went on to become a German philologist and historian of philosophy, pursued a career in academia,  and received a Ph.D. in ancient literature and art history at Berlin’s Humboldt University. Then, after the war, she become a professor at Humboldt University, where she worked until her death in 1998. Just before her death she recorded 77 cassette tapes of audio with her son, Hermann. In the tapes, for the first time, Marie chronicled her experience during the Nazi reign. They were later compiled into a book called, Underground in Berlin: A Young Woman’s Extraordinary Tale of Survival in the Heart of Nazi Germany. She became known to larger audiences for this, her autobiographical account of the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany, which was published posthumously. Marie died on September 16, 1998. She returned to her original identity only on her deathbed. Her mother died of cancer in 1938. Her father died in 1941. She is survived by her only son, Hermann Simon.

and received a Ph.D. in ancient literature and art history at Berlin’s Humboldt University. Then, after the war, she become a professor at Humboldt University, where she worked until her death in 1998. Just before her death she recorded 77 cassette tapes of audio with her son, Hermann. In the tapes, for the first time, Marie chronicled her experience during the Nazi reign. They were later compiled into a book called, Underground in Berlin: A Young Woman’s Extraordinary Tale of Survival in the Heart of Nazi Germany. She became known to larger audiences for this, her autobiographical account of the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany, which was published posthumously. Marie died on September 16, 1998. She returned to her original identity only on her deathbed. Her mother died of cancer in 1938. Her father died in 1941. She is survived by her only son, Hermann Simon.

We have all heard of the atrocities that took place in Nazi Germany regarding the Jewish people. And many people might have seen the movie called Schindler’s List. When the movie came out, I did not have a real interest in the old war movies, but I really should have in this one, because it is not your typical war movie. The movie documents the actions of a member of the Nazi Party, who saw something that was morally wrong, and did something about it.

We have all heard of the atrocities that took place in Nazi Germany regarding the Jewish people. And many people might have seen the movie called Schindler’s List. When the movie came out, I did not have a real interest in the old war movies, but I really should have in this one, because it is not your typical war movie. The movie documents the actions of a member of the Nazi Party, who saw something that was morally wrong, and did something about it.

Schindler wasn’t what would be considered a moral upstanding citizen to the Christian way of thinking. He married Emilie Pelzl at nineteen, but was never without a mistress or two. When his family’s business went under, he presided over the the proceedings, and then became a salesman when opportunity came knocking in the form of the war. Schindler was never one to miss a chance to make money. He saw opportunity in Poland, so he marched in on the heels of the SS. Soon, he was deep into the black-market and the underworld..making friends with the Gestapo officials along the way…softening them up with women, money and illicit booze.

It was his newfound connections that helped him acquire the factory in Krakow during the German occupation of Poland, which he ran with the cheapest labor around…namely the Jewish people from the nearby Jewish ghetto. Schindler was a hard man, and didn’t care much about others, but somewhere along the line, something changed. When the Nazis decided to liquidate the ghetto, he persuaded the officials to allow the transfer of his workers to the Plaszow labor camp. I’m not sure what they workers thought of that situation right away, but in the end, to saved them from deportation to the death camps, for which they were grateful.

By 1944, Hitler had become more and more crazed, and all the Jews at Plaszow were to be sent to Auschwitz, but Schindler couldn’t bear to see his workers murdered by Hitler. Schindler decided to take a huge risk, and bribe the officials into allowing him to keep his workers and set up a factory in a safer location in occupied Czechoslovakia. Miraculously, they agreed to let him have his workers, probably thinking of the factory’s production, and not the fact that these Jews would not meet the horrible fate awaiting them in the death camps. So, Schindler gave them a list of his workers, and of course, that is where the name of the movie came from. By the war’s end, Schindler was penniless, but he had saved 1,200 Jews. And that makes him a very rich man, indeed. In 1962, he was declared a Righteous Gentile by Yad Vashem, Israel’s official agency for remembering the Holocaust. Oskar Schindler died on this day, October 9, 1974, and according to his wishes, he was buried in Israel at the Catholic cemetery on Mount Zion.

Fire safety measures have vastly improved over the years, but in the early 1900s, no such safety measures existed. That would prove deadly on March 25, 1911 in New York City. People didn’t really know about materials that were more flammable, other than wood. Nevertheless, wood was the main material used in buildings, and in fact, still is today. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory was owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris. It was located in the top three floors of the Asch Building, on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, in Manhattan. These days that is not really a place we would expect to see a factory…much less a sweatshop, but the Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s factory was a true sweatshop. They employed mostly young immigrant women who worked in a cramped space at lines of sewing machines. Nearly all the workers were teenaged girls who did not speak English and made only about $15 per week working 12 hours a day, every day.

Fire safety measures have vastly improved over the years, but in the early 1900s, no such safety measures existed. That would prove deadly on March 25, 1911 in New York City. People didn’t really know about materials that were more flammable, other than wood. Nevertheless, wood was the main material used in buildings, and in fact, still is today. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory was owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris. It was located in the top three floors of the Asch Building, on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, in Manhattan. These days that is not really a place we would expect to see a factory…much less a sweatshop, but the Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s factory was a true sweatshop. They employed mostly young immigrant women who worked in a cramped space at lines of sewing machines. Nearly all the workers were teenaged girls who did not speak English and made only about $15 per week working 12 hours a day, every day.

In 1911, the Asch Building had four elevators with access to the factory floors, but only one was fully operational and the workers had to file down a long, narrow corridor in order to reach it. There were also two stairways down to the street, but one was locked from the outside to prevent stealing and the door of the other only opened inward. The fire escape was so narrow that it would have taken hours for all the workers to use it, even in the best of circumstances…in an emergency, it was almost useless. Pretty much everyone knew about the danger of fire in factories like the Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory, but high levels of corruption in both the garment industry and city government ensured that no useful precautions were taken to prevent fires. The  problem was that making the factories safe cost money, and dug into the profits, so the owners didn’t want to do what was necessary to save lives. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory’s owners were known to be particularly anti-worker in their policies and had played a critical role in breaking a large strike by workers the previous year.

problem was that making the factories safe cost money, and dug into the profits, so the owners didn’t want to do what was necessary to save lives. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory’s owners were known to be particularly anti-worker in their policies and had played a critical role in breaking a large strike by workers the previous year.

On March 25, a Saturday afternoon, there were 600 workers at the factory when a fire began in a rag bin. The manager attempted to use the fire hose to extinguish it, but was unsuccessful. The hose was rotted and its valve was rusted shut. They were at the mercy of the raging inferno. The fire grew and the workers panicked. They tried to exit the building by the elevator, but it could only hold 12 people and the operator was able to make just four trips before it broke down due to the heat and flames. In a desperate attempt to escape the flames. The girls left behind waiting for the elevator plunged down the shaft to their deaths. The girls who fled by way of the stairwells also met awful fates. When they found a locked door at the bottom of the stairs, many were burned alive. In all, 145 workers between the ages of 14 and 43, mostly women and mostly in their teens and early twenties, died that day. Six of them would not be identified until February, 2011…100 years later.

Once the fire was reported, the firefighters tried to put it out, but their ladders would only reach the seventh floor. The fire was on the eighth floor. When escape was proven to be impossible, the girls, desperate to escape the searing heat and flames, began to jump. The bodies of those who jumped landed on the hoses, hampering the flow. The firemen got out nets to catch the girls, but they jumped three at a time, tearing the nets. The nets were of no real help. Within 18 minutes, it was all over. Of the dead, 49 workers had burned to death or been suffocated by smoke, 36 were dead in the elevator shaft and 58 died from jumping to the sidewalks. Two  more died later from their injuries. The workers’ union set up a march on April 5 on New York’s Fifth Avenue to protest the conditions that had led to the fire. It was attended by 80,000 outraged people. Despite a good deal of evidence that the owners and management had been horribly negligent in the fire, a grand jury failed to indict them on manslaughter charges. The tragedy did result in some good, however. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union was formed in the aftermath of the fire and the Sullivan-Hoey Fire Prevention Law was passed in New York that October. Both were crucial in preventing similar disasters in the future. Still, I think that it will take the memory of the victims of corruption to ever really inspire people to change the way things are.

more died later from their injuries. The workers’ union set up a march on April 5 on New York’s Fifth Avenue to protest the conditions that had led to the fire. It was attended by 80,000 outraged people. Despite a good deal of evidence that the owners and management had been horribly negligent in the fire, a grand jury failed to indict them on manslaughter charges. The tragedy did result in some good, however. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union was formed in the aftermath of the fire and the Sullivan-Hoey Fire Prevention Law was passed in New York that October. Both were crucial in preventing similar disasters in the future. Still, I think that it will take the memory of the victims of corruption to ever really inspire people to change the way things are.

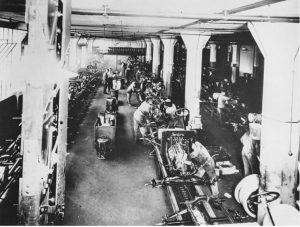

These days, so many things are automated, that we hardly know how to work in an environment that requires us to hand build everything. Machines often make most of the things we buy, but it wasn’t always so. In the beginning of the automobile age, cars had to be put together by hand, making it a very slow process. If you are going to sell mass quantities of something, you have to be able to mass produce it. Selling mass quantities of his now famous, Model T, was exactly what Henry Ford wanted to do. So he came up with a way to move the vehicles from one worker to another. Each worker had a specific part they were to place, before the vehicle moved on down the line. Ford’s dream was to make the automobile available to everyone, not just the rich, who could afford to order the new fangled machines. Of course, most people those days didn’t really think that the automobile would ever amount to much, but as we all know, they were very wrong. The automobile has become an absolute necessity for most people…except maybe some in the bigger cities, where owning a car isn’t really feasible because of parking issues and heavy traffic.

These days, so many things are automated, that we hardly know how to work in an environment that requires us to hand build everything. Machines often make most of the things we buy, but it wasn’t always so. In the beginning of the automobile age, cars had to be put together by hand, making it a very slow process. If you are going to sell mass quantities of something, you have to be able to mass produce it. Selling mass quantities of his now famous, Model T, was exactly what Henry Ford wanted to do. So he came up with a way to move the vehicles from one worker to another. Each worker had a specific part they were to place, before the vehicle moved on down the line. Ford’s dream was to make the automobile available to everyone, not just the rich, who could afford to order the new fangled machines. Of course, most people those days didn’t really think that the automobile would ever amount to much, but as we all know, they were very wrong. The automobile has become an absolute necessity for most people…except maybe some in the bigger cities, where owning a car isn’t really feasible because of parking issues and heavy traffic.

On this day, October 7, 1913, Henry Ford’s entire Highland Park, Michigan automobile factory started running on a continuously moving assembly line where the chassis, which is the automobile’s frame, was assembled using a state of the art, revolutionary industrial technique. A motor and rope pulled the chassis past workers and parts on the factory floor, cutting the man hours required to complete one “Model T” from 12-1/2 hours to six. Within a year, improvements in the assembly line reduced the time required to 93 man minutes…to build a car!! That is just amazing to me. The increase in productivity brought about by Ford’s use of the moving assembly line allowed him to drastically reduce the cost of the Model T. Ford’s goal was to make the car affordable to ordinary consumers. This new process allowed him to realize that goal, and before long, everyone had an automobile.

Since the days of Ford’s antiquated assembly line, automation has vastly improved. These days machines can do so much more that their human counterparts. Of course, that has eliminated more than just a few jobs, but as people have learned to run that equipment, new jobs have opened up. In this world, time doesn’t stand still, and progress waits for no man. You have to learn the new skills as they come along so that you can keep up in this fast paced automated world. Assembly lines have come a long way since those old days, and it’s a good thing, because the automobile is now in very high demand around the world, and people won’t wait very long to get one.