enemies

The 83rd anniversary of Pearl Harbor, at least for the Baby Boomer generation and older, prompts reflection on the United States’ stance of often waiting for an initial attack before responding. While this is not always the case, it appears to be a common scenario. The US strives to act as a peacemaker, and the decision to go to war is never taken lightly due to the grave consequences of taking lives. Typically, numerous warnings are issued before any action is taken, and frequently, it’s too late to preemptively strike. The first to strike is often labeled the aggressor, but there are times when ample warning signals an imminent attack, yet the response is still delayed, until the attack occurs, resulting in loss of life and leaving the survivors to deal with the aftermath rather than considering an immediate counterstrike. Of course, the reverse is hard to deal with too, because we would come off as being the aggressor, and that just isn’t our style.

The 83rd anniversary of Pearl Harbor, at least for the Baby Boomer generation and older, prompts reflection on the United States’ stance of often waiting for an initial attack before responding. While this is not always the case, it appears to be a common scenario. The US strives to act as a peacemaker, and the decision to go to war is never taken lightly due to the grave consequences of taking lives. Typically, numerous warnings are issued before any action is taken, and frequently, it’s too late to preemptively strike. The first to strike is often labeled the aggressor, but there are times when ample warning signals an imminent attack, yet the response is still delayed, until the attack occurs, resulting in loss of life and leaving the survivors to deal with the aftermath rather than considering an immediate counterstrike. Of course, the reverse is hard to deal with too, because we would come off as being the aggressor, and that just isn’t our style.

On December 7, 1941, the United States found itself in a precarious position. Despite repeatedly warning Japan, the United States using the Hull Note as a show of the ultimate caution, tried to avoid entering World War II. The Hull Note officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States of America before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) and the Japanese declaration of war (seven and a half hours after the attack began). Unfortunately, Japan to all that as a show of weakness. Nevertheless, knowing that Japan would likely not comply, and essentially declaring war, the US still hoped they would proceed slowly, perhaps  even reconsider their course. Conversely, Japan acted swiftly, dispatching their strike force towards Pearl Harbor and simultaneously sending a decoy towards Thailand to mislead the US. Then, believing an attack on Thailand was imminent, President Roosevelt implored Emperor Hirohito via telegram to act “for the sake of humanity” and prevent further devastation. The US endeavored to maintain peace.

even reconsider their course. Conversely, Japan acted swiftly, dispatching their strike force towards Pearl Harbor and simultaneously sending a decoy towards Thailand to mislead the US. Then, believing an attack on Thailand was imminent, President Roosevelt implored Emperor Hirohito via telegram to act “for the sake of humanity” and prevent further devastation. The US endeavored to maintain peace.

After transmitting the telegram, President Roosevelt was working on his stamp collection alongside his personal advisor, Harry Hopkins. They deliberated over Japan’s rejection of the Hull Note. Hopkins proposed a preemptive strike by America, but President Roosevelt maintained that it was not an option. Unbeknownst to them, it was already too late for a first strike…time had run out. The Japanese forces were en route to Pearl Harbor, where a significant segment of the Pacific Fleet lay anchored, vulnerable to attack. The impending ambush would devastate 18 US ships, including the Arizona, Virginia, California, Nevada, and West Virginia, either destroyed, sunk, or capsized. Over 180 aircraft were destroyed on the ground, with an additional 150 damaged, leaving a mere 43 operational. American casualties exceeded 3,400, with over 2,400 fatalities—1,000 of which occurred on the Arizona alone. The Japanese incurred fewer than 100 losses.

It often appears that the party who strikes first, swiftly and with the element of surprise, ultimately fares better. The side caught off guard, or the one that ignored the warning signs, is usually defeated. With one of the strongest military forces on Earth, America should not be taken by surprise. I believe that overconfidence in one’s strength, leading to a lack of vigilance, can result in the downfall of even the mightiest. The United States has been such a force, but our reluctance to preemptively strike seems to invite repeated attacks without warning. It is only after such attacks that we seem to retaliate.

It’s indeed a dilemma, perhaps reflective of President Roosevelt’s perspective. If we strike first, we’re vilified globally as the aggressors, akin to those at Pearl Harbor. If we don’t, we face condemnation from our own citizens. Moreover, our intelligence isn’t infallible, leading to situations like the surprise attack on December 7th, 1941, when we expected honor from an adversary who did not feel bound by it. It seems that although being

attacked unprovoked is undesirable, we must still act honorably and not launch a preemptive strike merely based on anticipated aggression. Otherwise, we become indistinguishable from those nations we confront in war for their acts of invasion. Nevertheless, it remains a huge challenge to always be the nation that does the right things, especially when there is a profound mistrust of our enemies…because we know better.

attacked unprovoked is undesirable, we must still act honorably and not launch a preemptive strike merely based on anticipated aggression. Otherwise, we become indistinguishable from those nations we confront in war for their acts of invasion. Nevertheless, it remains a huge challenge to always be the nation that does the right things, especially when there is a profound mistrust of our enemies…because we know better.

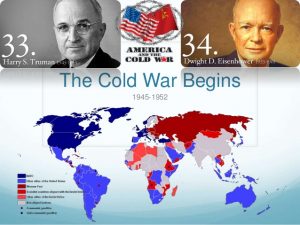

In any wartime situation, there always seem to be those who think the United States should not get involved…mostly because they think that if we just stay out of it, the enemy will leave us alone. Of course, history does not prove that theory. When we look at the wars that the United States has been drawn into, only after we were attacked too, we find that the enemy always intended to take on the United States too, and we were only delaying the inevitable. It seems like every wartime president has had to deal with the naysayers, and President Eisenhower was no different. During the Cold War years when the Communists were trying to take over the world, Eisenhower chose a strong United States defense against it, but his view of a strong defense was much different that General Hoyt Vandenberg’s view. Vandenberg wanted a massive increase in conventional land, air, and sea forces, while Eisenhower said that a cheaper and more efficient defense could be built around the nation’s nuclear arsenal. Senator Robert Taft argued that if efforts to reach a peace agreement in Korea failed, the United States should withdraw from the United Nations forces and make its own policy for dealing with North Korea, basically a completely independent foreign policy, or what one “might call the ‘fortress’ theory of defense.” While both of these suggestions might seem like the best course of action, history tells us that Senator Taft’s suggestion would make us look weak, and possibility bring about attacks on the United States, and while I would tend to agree with General Vandenberg, that we need a strong defense system, I also understand that as technology changes, nations must change with it. Having hundreds of fighter planes is not necessary, if a few can drop a bomb that will settle the matter once and for all. It is similar to the use of pen and paper when we live in a computer age.

In any wartime situation, there always seem to be those who think the United States should not get involved…mostly because they think that if we just stay out of it, the enemy will leave us alone. Of course, history does not prove that theory. When we look at the wars that the United States has been drawn into, only after we were attacked too, we find that the enemy always intended to take on the United States too, and we were only delaying the inevitable. It seems like every wartime president has had to deal with the naysayers, and President Eisenhower was no different. During the Cold War years when the Communists were trying to take over the world, Eisenhower chose a strong United States defense against it, but his view of a strong defense was much different that General Hoyt Vandenberg’s view. Vandenberg wanted a massive increase in conventional land, air, and sea forces, while Eisenhower said that a cheaper and more efficient defense could be built around the nation’s nuclear arsenal. Senator Robert Taft argued that if efforts to reach a peace agreement in Korea failed, the United States should withdraw from the United Nations forces and make its own policy for dealing with North Korea, basically a completely independent foreign policy, or what one “might call the ‘fortress’ theory of defense.” While both of these suggestions might seem like the best course of action, history tells us that Senator Taft’s suggestion would make us look weak, and possibility bring about attacks on the United States, and while I would tend to agree with General Vandenberg, that we need a strong defense system, I also understand that as technology changes, nations must change with it. Having hundreds of fighter planes is not necessary, if a few can drop a bomb that will settle the matter once and for all. It is similar to the use of pen and paper when we live in a computer age.

President Eisenhower was no stranger to sending the military might of the United States out to attack the enemy, and in his days as a general, he made those decisions every day, but as every one should realize, the  more men you have to send, the more possibility of losing them. The decision to send soldiers to their deaths was not one that Eisenhower ever took lightly. With a strong nuclear arsenal, the enemy nation knew that they had better think twice before taking on the United States.

more men you have to send, the more possibility of losing them. The decision to send soldiers to their deaths was not one that Eisenhower ever took lightly. With a strong nuclear arsenal, the enemy nation knew that they had better think twice before taking on the United States.

Without naming either man, President Eisenhower responded to both during a speech at the National Junior Chamber of Commerce meeting in Minneapolis. His forceful speech struck back at critics of his Cold War foreign policy. He insisted that the United States was committed to the worldwide battle against communism and that he would maintain a strong United States defense. It was just a few months into his presidency, and the Korean War still raging, but Eisenhower laid out his basic approach to foreign policy with this speech. He began by characterizing the Cold War as a battle “for the soul of man himself.” He rejected Taft’s idea that the United States should pursue isolationism, and instead he insisted that all free nations had to stand together saying, “There is no such thing as partial unity.” To Vandenberg’s criticisms of the new Air Force budget, in which the president proposed a $5 billion cut from the Air Force budget, Eisenhower explained that vast numbers of aircraft were not needed in the new atomic age. Just a few planes armed with nuclear weapons could “visit on an enemy as much explosive violence as was hurled against Germany by our entire air effort throughout four years of World War II.” With this speech, Eisenhower thus pointed out the two major points of what came to be known at the time as his “New Look” foreign policy. First was his advocacy of multi-nation responses to communist aggression in preference to unilateral action by the United States. Second was the idea that came to be known as the “bigger bang for the buck” defense strategy.

Anytime a nation is facing war, it is a stressful time for its people, but no nation will do well using the isolation strategy, because a nation that appears to be weak in its own defense, will ultimately become a target for attack. I am not an advocate for the United Nations, and in fact, I believe we need to disband the United Nations, but I do believe that a nation must have allies…nations with like values, who are willing to go to war to back up their allies, and that we must not allow bully nations to take over smaller nations, because that only strengthens their resolve to expand further. I also believe that when technology becomes available, it must be properly combined with human forces to achieve the best result in the most efficient way.

Anytime a nation is facing war, it is a stressful time for its people, but no nation will do well using the isolation strategy, because a nation that appears to be weak in its own defense, will ultimately become a target for attack. I am not an advocate for the United Nations, and in fact, I believe we need to disband the United Nations, but I do believe that a nation must have allies…nations with like values, who are willing to go to war to back up their allies, and that we must not allow bully nations to take over smaller nations, because that only strengthens their resolve to expand further. I also believe that when technology becomes available, it must be properly combined with human forces to achieve the best result in the most efficient way.