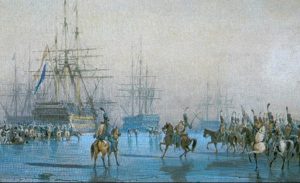

dutch fleet

Anytime a country, engaged in a war, can capture a ship belonging to their enemy, they will find themselves strategically in a better position than before, but to capture the entire fleet…now that can mean the difference between winning and losing the war. On January 23, 1795, at Den Helder, North Holland, Netherlands, an extremely rare occurrence took place when a French Revolutionary Hussar cavalry regiment came across a Dutch fleet at anchor in the Nieuwediep, just east of the town of Den Helder. While it was not unusual to come across ships at anchor, what is extremely rare is an interaction between warships and cavalry. One being on land and one on the water, usually prevented any interaction, since the men on horses couldn’t carry guns big enough to reach the ships under normal conditions. The difference in this situation was, of course, that the Dutch fleet was frozen at anchor, not simply sitting at anchor. They had no place they could go. The men on the Dutch fleet knew that they were “sitting ducks” with no recourse, so after some of the Hussars had approached across the frozen Nieuwediep, a negotiation began. It was decided that all 14 Dutch warships would remain at anchor. It was a pretty easy negotiation, because in reality, the Dutch fleet had no other choice. They were now prisoners of war and their capture had happened without violence or even a battle. In an extremely rare even the Dutch fleet was captured by the French Revolutionary Hussars on horseback.

Anytime a country, engaged in a war, can capture a ship belonging to their enemy, they will find themselves strategically in a better position than before, but to capture the entire fleet…now that can mean the difference between winning and losing the war. On January 23, 1795, at Den Helder, North Holland, Netherlands, an extremely rare occurrence took place when a French Revolutionary Hussar cavalry regiment came across a Dutch fleet at anchor in the Nieuwediep, just east of the town of Den Helder. While it was not unusual to come across ships at anchor, what is extremely rare is an interaction between warships and cavalry. One being on land and one on the water, usually prevented any interaction, since the men on horses couldn’t carry guns big enough to reach the ships under normal conditions. The difference in this situation was, of course, that the Dutch fleet was frozen at anchor, not simply sitting at anchor. They had no place they could go. The men on the Dutch fleet knew that they were “sitting ducks” with no recourse, so after some of the Hussars had approached across the frozen Nieuwediep, a negotiation began. It was decided that all 14 Dutch warships would remain at anchor. It was a pretty easy negotiation, because in reality, the Dutch fleet had no other choice. They were now prisoners of war and their capture had happened without violence or even a battle. In an extremely rare even the Dutch fleet was captured by the French Revolutionary Hussars on horseback.

Jean-Charles Pichegru was the leader of the French units…the 8th Hussar Regiment and the Voltigeur company of the 15th Line Infantry Regiment of the French Revolutionary Army, who had been assigned to invade the Dutch Republic. The Dutch fleet was commanded by captain Hermanus Reintjes. This rare event took place during the War of the First Coalition, which was part of the French Revolutionary Wars. The little town of Den Helder is located at the tip of the North Holland peninsula, south of the island of Texel, near the shallow Zuiderzee bay (which means Southern Sea). The Zuiderzee was closed off and partly drained in the 20th century, and what is left of it now forms the freshwater IJsselmeer.

Nevertheless, in the fall of 1794, during the War of the First Coalition of the French Revolutionary Wars, the area was the site of one of the most bizarre captures in history. That day, the Dutch proclaimed the Batavian Republic, effectively ending the war with France and allying itself with France instead. Suddenly, the French were no longer enemies of the Dutch, which seems like a good move in light of the capture. Nevertheless, there were those among the Dutch Navy and the army there who remained loyal to the Stadtholder, and there were fears that Navy ships from Den Helder might sail for England to rejoin William V, Prince of Orange. For that reason, the new Batavian interim Government issued orders to all its fleets at Vlissingen, Hellevoetsluis and at Den Helder, not to fight against the French if they appeared, and to keep the ships at anchor to make sure they could be ready to defend the new Republic against the British.

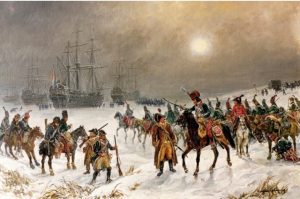

This event might not have been possible, were it not for the fact that the winter of 1794–1795 was exceptionally cold, causing the Zuiderzee to freeze. Pichegru saw an opportunity and ordered General of Brigade Jan Willem de Winter to lead a squadron of the 8th Hussar Regiment to Den Helder. De Winter had been serving with the French since 1787 and would later command the Dutch fleet in the disastrous Battle of Camperdown. So, while he was successful in one operation, he might not have been the best leader in the long

run. Still, the operation was carried out with no casualties. The French simply received the assurance from the Dutch captain that the vessels and their crews would remain at anchor until the political situation in the Dutch Republic would have become clear. The situation was finally settled in May 1795 under the Treaty of The Hague, when the Batavian Republic officially became a French ally. Now, its ships would serve a common cause.

run. Still, the operation was carried out with no casualties. The French simply received the assurance from the Dutch captain that the vessels and their crews would remain at anchor until the political situation in the Dutch Republic would have become clear. The situation was finally settled in May 1795 under the Treaty of The Hague, when the Batavian Republic officially became a French ally. Now, its ships would serve a common cause.

Ice flows in the world’s waterways has been known to freeze ships in place, leaving them stuck, often damaged, and sometimes…captured. The date was January 23, 1795, and the Dutch fleet was at anchor in the Zuiderzee, fifty miles north of Amsterdam. It was the height of the French Revolution, and the winter in the area was not cooperating with the fleet. In fact, some people in the port town of Den Helder said it was the worst winter they had seen in many years.

Ice flows in the world’s waterways has been known to freeze ships in place, leaving them stuck, often damaged, and sometimes…captured. The date was January 23, 1795, and the Dutch fleet was at anchor in the Zuiderzee, fifty miles north of Amsterdam. It was the height of the French Revolution, and the winter in the area was not cooperating with the fleet. In fact, some people in the port town of Den Helder said it was the worst winter they had seen in many years.

A unit of French soldiers was approaching the town that night, under the command of brigadier-general De Winter. Everyone in town knew it. A few days earlier, seven self-governing provinces had declared independence and a loose alliance. The old Republic had been ousted. Den Helder was now part of the newly declared Batavian Republic. Emotions were running high with excitement among the people, and the arrival of soldiers from the revolutionary new French Republic was welcomed. Having the Dutch Fleet in the port was oppressive, and they were ready for it to end. There was much talk of France, and of all that had been achieved there in recent years. The revolution was real, the monarchies had fled, and battles on sea and on land were being won. A bright future, free from the tyranny of the old leaders and old politics was within their grasp. The people felt hope again.

The only people who didn’t know about the French cavalry was the men on the Dutch fleet…not that it would have really mattered. It was almost midnight when the French detachment arrived. It was freezing, and the men were bundled in every garment they possessed…a great troop of horsemen riding double toward the port. People left the inns and public houses, cheering them on, and pointing out toward the Zuiderzee, where the Dutch fleet was anchored. The captain of the cavalry dismounted at the water’s edge…almost amazed. The reports were true. There, in the crisp light of the moon and stars he could see ships anchored in the bay, but he was looking not across the water. He was gazing across a great sheet of grey ice. The Zuiderzee, was shallow and fed by fresh water…and it had frozen over. The fleet in the bay was icebound and trapped. The fleet of the old Dutch Republic must have been sitting there for days, he said, but until yesterday its presence had been hidden from the town by fog and snow. Layers of snowfall had frozen and thickened the ice, which was now many feet deep.

After the scouts checked out the situation and returned, the Captain asked, “How many ships?” When he received his answer, he made his decision. This was too good a chance to miss. Messages were dispatched to General De Winter, and the soldiers were given their orders. They were to wrap the horse’s hooves in cloth, both to muffle the sound of their approach and to minimize the chance of the heavy hooves and steel horseshoes shattering the ice. They were to approach slowly and cautiously, and they were to be silent. They were to listen for the cracking of the ice, and be prepared to make an careful retreat if necessary. Onto the ice they went, horsemen and infantry, silent as the clouds of vapor that streamed from their mouths and noses as they breathed. There were eighty five warships and twenty merchant vessels trapped in the ice. The fleet represented most of the naval power of the deposed Dutch Republic, its capture would be a huge win for the French. As they advanced carefully across the ice, their ears strained for the creaking noises which would herald disaster. They became more confident. The ice held. They gathered speed. The dark ships growing larger as they came closer.

There were a few lights coming from the fleet, and the captain stopped his men short before they reached the first vessels. As quietly as possible, he sent men on foot in between the sides of the great ships. It took an hour for his men to survey the situation, and to identify the command vessel. This was a great 86 gunner, near to the French position. The captain gave his orders quickly and quietly. A detachment of horsemen was sent back, with orders to ride the shore of the Zuiderzee and establish exactly how far out the ice extended. Then, the captain dismounted and walked with the great body of his infantry round to the great command ship. They carried ropes and grappling hooks. The captain had his men prime their rifles, and then they threw hooks with ropes onto the ships.

At the sound of the first hooks on the deck a dozing watchman woke up. By the time he was awake enough to raise a cry, the captain and hundred men were on the deck. The watchman called out and ran toward the great bell, meaning to raise the alarm, but he slipped on the icy deck. There was a rush of feet, and he found himself staring up at the barrel of a musket. “Silence!” hissed the soldier. The command ship had been boarded. When the admiral was rousted from his bed and presented himself on deck, he knew that there was no hope of  resistance. The conversation he had with the young French captain of the cavalry was courteous. There would be more French troops arriving at first light, and General De Winter would arrive with them. De Winter was now the master of the Dutch fleet, and he would give clear orders. The admiral had no choice, but to give orders that the fleet surrender. When De Winter arrived in the morning the whole fleet was secured and explored in the grey morning light. The captain of the cavalry was promoted on the spot, and the admiral and his crews swore allegiance to the French Republic. A great victory had been won, without a drop of blood spilled or a single shot fired. It was the only such event ever recorded in military history.

resistance. The conversation he had with the young French captain of the cavalry was courteous. There would be more French troops arriving at first light, and General De Winter would arrive with them. De Winter was now the master of the Dutch fleet, and he would give clear orders. The admiral had no choice, but to give orders that the fleet surrender. When De Winter arrived in the morning the whole fleet was secured and explored in the grey morning light. The captain of the cavalry was promoted on the spot, and the admiral and his crews swore allegiance to the French Republic. A great victory had been won, without a drop of blood spilled or a single shot fired. It was the only such event ever recorded in military history.