doctors

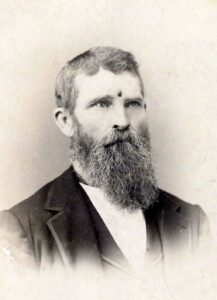

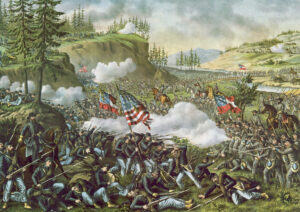

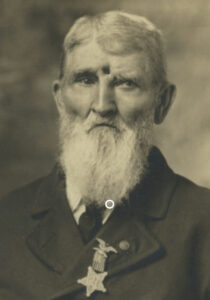

Anytime a soldier goes to war, the possibility exists that they will be severely wounded or even killed in action, but I don’t think anyone expected the events of September 19, 1863. It was the middle of the Civil War, and Jacob C Miller was a private in Company K, 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment. The company was fighting in the Battle of Chickamauga near Brock Field in southeastern Tennessee. One of the fastest ways to “get dead” is to get shot in the head. There is something about a bullet hitting the skull that puts an end to life pretty quickly…most of the time, anyway.

Anytime a soldier goes to war, the possibility exists that they will be severely wounded or even killed in action, but I don’t think anyone expected the events of September 19, 1863. It was the middle of the Civil War, and Jacob C Miller was a private in Company K, 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment. The company was fighting in the Battle of Chickamauga near Brock Field in southeastern Tennessee. One of the fastest ways to “get dead” is to get shot in the head. There is something about a bullet hitting the skull that puts an end to life pretty quickly…most of the time, anyway.

Maybe it was the type of bullets used in the Civil War, but no matter how it happened, I don’t think anyone would disagree with me when I say that living after taking a bullet between the eyes was a miracle. Jacob C Miller was just such a miracle man. After being shot, Miller crumpled to the ground. I’m sure everyone thought it was over, but Miller said later that he could hear the words of his captain, who said, “It’s no use to remove poor Miller, for he is dead.” The company, believing he was dead, moved on. Now, just imagine the shock when Miller became conscious and found himself alone. He raised up in a sitting position. Curiosity caused him to feel his wound. Clearly there was damage done. Miller’s left eye was out of place, and he tried to  place it back, but had to move the crushed bone back together, or as near together as he could first. Once the eye was in its proper place, he bandaged the eye the best he could with his bandana. Then he began the journey to get help. Miller struggled to follow his company, until he was finally picked up by a liter party, and taken for treatment.

place it back, but had to move the crushed bone back together, or as near together as he could first. Once the eye was in its proper place, he bandaged the eye the best he could with his bandana. Then he began the journey to get help. Miller struggled to follow his company, until he was finally picked up by a liter party, and taken for treatment.

When he was taken to the doctors, and they examined him, they said that they were able to see his pulsating brain quite clearly. That said, we know that the bullet wasn’t somehow stopped by his skull. It had actually entered the brain lining, or at least into the skull bone. At that point, nothing was done with the bullet, and Miller was sent home to Logansport, Indiana. Doctors there were hesitant to remove the bullet, because they thought Miller would die, and somehow, he seemed to be functioning ok with the bullet in place. In the end  they did remove about a third of the bullet, and Miller went on to live his life. Nevertheless, more pieces of the bullet simply fell out decades later. It was as if his body just rejected the foreign pieces of lead and moved them out of his head. It was a good thing, because the pressure on the bullet fragments during times of illness caused his to become delirious. Once the fragments fell out, that stopped.

they did remove about a third of the bullet, and Miller went on to live his life. Nevertheless, more pieces of the bullet simply fell out decades later. It was as if his body just rejected the foreign pieces of lead and moved them out of his head. It was a good thing, because the pressure on the bullet fragments during times of illness caused his to become delirious. Once the fragments fell out, that stopped.

Miller was born on August 4, 1840, in Bellevue, Ohio. He was shot on September 19, 1863, at the age of 23 years. Private Jacob C Miller lived an amazing 54 years with an open wound in his head. The wound never fully healed, but did not fully penetrate his skull, and apparently the brain area did close over, and caused no damage to his brain. He died January 13, 1917, in Omaha, Nebraska at the age of 76 years. No cause of death is mentioned, but I guess we know it wasn’t a gunshot wound to the head.

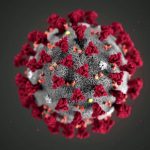

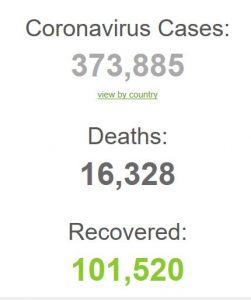

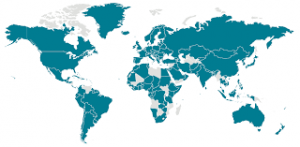

Finding ourselves in the middle of a global pandemic has placed many Americans, and in fact, most Americans, as well as the people of other countries, in a world suddenly changed. Will it be forever changed? Well, that remains to be seen. What we do know is that life as we knew it…just days ago for some of us, is nothing like it was before. We find ourselves being told to “stay at home” unless we happen to be one of the essential workers…doctors, nurses, CNAs and other hospital workers, grocery store employees, restaurant workers (who can only handle pick-up or delivery orders, because the dining rooms are closed), first responders (police, fire, and ambulance), necessary city or town workers (including, of course, government officials), mail carriers, truck drivers and delivery people. The rest of us are supposed to stay home accept for getting food, groceries, medicine, gasoline, medical appointments, and outdoor exercise…all while practicing social distancing (staying 6 feet away from other people). That, of course, means no hugging, hand shaking, high fives, elbow bumps or even foot taps, which had prior become the new normal. Many people are wearing masks and of course, washing their hands and using hand sanitizer, and not touching their faces.

Finding ourselves in the middle of a global pandemic has placed many Americans, and in fact, most Americans, as well as the people of other countries, in a world suddenly changed. Will it be forever changed? Well, that remains to be seen. What we do know is that life as we knew it…just days ago for some of us, is nothing like it was before. We find ourselves being told to “stay at home” unless we happen to be one of the essential workers…doctors, nurses, CNAs and other hospital workers, grocery store employees, restaurant workers (who can only handle pick-up or delivery orders, because the dining rooms are closed), first responders (police, fire, and ambulance), necessary city or town workers (including, of course, government officials), mail carriers, truck drivers and delivery people. The rest of us are supposed to stay home accept for getting food, groceries, medicine, gasoline, medical appointments, and outdoor exercise…all while practicing social distancing (staying 6 feet away from other people). That, of course, means no hugging, hand shaking, high fives, elbow bumps or even foot taps, which had prior become the new normal. Many people are wearing masks and of course, washing their hands and using hand sanitizer, and not touching their faces.

Many of these things are common sense, and some are things we have done for a while now, but other things are so new and very foreign to us. We are a mobile society, and staying home is very foreign to us. Schools and daycares are closed, making it difficult for the essential workers with children to get to work. Parents who never considered home-schooling, are forced to do so, as many schools will not open for the remainder of the school year. Non-essential workers find themselves working from home (if their jobs can feasibly allow that). The streets are almost deserted, and we find ourselves wondering if the few people we see out, have a legitimate reason to be out, or if they had simply gone rogue. Normally we care little for the goings on of other people on the street, and we are used to many people going many places. Most of us hardly notice the people around us going about their daily commutes or errands. We were too busy with our own lives to care about what others were doing. Now, however, we find ourselves looking at the people who are out and about, wondering if they really should be more responsible and stay at home.

As pandemics do, this one too shall pass, but what of our country. Will we start to be more caring for others? Will we work to get closer to our families, neighbors, and friends? Will we suddenly know that we can use a lot less of things that we may have been wasteful with before? Will we continue to pray over people and say things like “God Bless America,” or are these things just something we do because we have been caught up in the  moment? Or will we, like so many times before, forget about all this a year from now? It is my hope that we will step up and make some permanent changes in our lives. The people of the earth have maybe been very selfish, thinking only of ourselves and those we care about, but maybe we shouldn’t be that way. Life as we knew it changed with COVID19’s entrance on the world stage. What we do next will determine how history views the generations of people alive today. Will we be viewed as reckless and unfeeling, or will we be viewed as the most amazing generation ever to deal with a global disaster? The outcome really depends on us.

moment? Or will we, like so many times before, forget about all this a year from now? It is my hope that we will step up and make some permanent changes in our lives. The people of the earth have maybe been very selfish, thinking only of ourselves and those we care about, but maybe we shouldn’t be that way. Life as we knew it changed with COVID19’s entrance on the world stage. What we do next will determine how history views the generations of people alive today. Will we be viewed as reckless and unfeeling, or will we be viewed as the most amazing generation ever to deal with a global disaster? The outcome really depends on us.

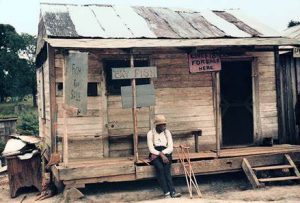

When the Great Depression hit, people in the upper-middle class, like doctors, lawyers, and other professionals, saw their incomes drop by 40%, but the middle class and low income Americans found themselves with nothing. They had no jobs and no money, and even if they did have those things, they couldn’t afford the things they needed. The prices for everything from food to clothing were much more than their meager income could buy much of. People began to move from place to place looking for a job…any job. The problem was that there were very few jobs, and lot of people standing in line to get them. The average American lived by the Depression-era motto: Use it up, wear it out, make do, or do without. People had to learn to be frugal. Clothes were patched when the started to wear out. People planted gardens and even kept little gardens in their kitchen. They stayed home, instead of evenings out. They were always in a private struggle to keep their cars or homes.

When the Great Depression hit, people in the upper-middle class, like doctors, lawyers, and other professionals, saw their incomes drop by 40%, but the middle class and low income Americans found themselves with nothing. They had no jobs and no money, and even if they did have those things, they couldn’t afford the things they needed. The prices for everything from food to clothing were much more than their meager income could buy much of. People began to move from place to place looking for a job…any job. The problem was that there were very few jobs, and lot of people standing in line to get them. The average American lived by the Depression-era motto: Use it up, wear it out, make do, or do without. People had to learn to be frugal. Clothes were patched when the started to wear out. People planted gardens and even kept little gardens in their kitchen. They stayed home, instead of evenings out. They were always in a private struggle to keep their cars or homes.

Paint was too expensive, so home fell into disrepair. As things got worse, things began to wear out, and people didn’t get rid of the junk. They simply put it out in the yard. I’m sure that they realized that every piece of junk had parts in it that could be used for repairs to something else. Everything could be reworked. They used the  backs of worn-out overall legs to make pants for little boys and overalls for babies. They didn’t have disposable diapers back then. They made diapers and underwear out of flour and sugar sacks. When the older kids outgrew their clothes, but they were too big for the younger kids, they made smaller clothes out of bigger hand-me-downs. If their shoes wore out before a year, the children went barefooted. Many people resorted to bartering…not only goods for goods, but work for work. They tried to make their homes and their lives pretty, even in depressing times. They used patterned chicken feed sacks to make curtains, aprons, and little girl’s dresses. Worn out socks were kept, so that they could patch another sock. Nothing was thrown away. They saved string that came loose from clothing and added it to a string ball for mending and sewing. Toilet paper was a luxury that many people couldn’t afford, so they used newspaper instead. They saved every scrap of material for making quilts. People learned not to waste anything.

backs of worn-out overall legs to make pants for little boys and overalls for babies. They didn’t have disposable diapers back then. They made diapers and underwear out of flour and sugar sacks. When the older kids outgrew their clothes, but they were too big for the younger kids, they made smaller clothes out of bigger hand-me-downs. If their shoes wore out before a year, the children went barefooted. Many people resorted to bartering…not only goods for goods, but work for work. They tried to make their homes and their lives pretty, even in depressing times. They used patterned chicken feed sacks to make curtains, aprons, and little girl’s dresses. Worn out socks were kept, so that they could patch another sock. Nothing was thrown away. They saved string that came loose from clothing and added it to a string ball for mending and sewing. Toilet paper was a luxury that many people couldn’t afford, so they used newspaper instead. They saved every scrap of material for making quilts. People learned not to waste anything.

Every part of the food was used. Potato peels were food, not waste. They made soup out of a few vegetables and a scrap of meat…for flavor only. They hunted for rabbits and fished to put what protein they could on the table. When there was nothing more to eat, they had lard sandwiches. I seriously doubt if many people went to  bed with a full stomach, but that didn’t mean that you turned away a stranger who was hungry. These people knew hw bad things were for them, and so they helped their neighbors. Nevertheless, during the Great Depression, suicide rates in the United States reached an all-time high, topping 22 suicides per 100,000 people. The living conditions were deplorable, and many people couldn’t take it. They felt that somehow they were at fault. still, for the majority of Americans, that didn’t mean that they gave up. Neighbor looked out for neighbor, and families came together to support each other, and while the effects of the Great Depression lasted for 12 years, this too passed, and the nation healed again.

bed with a full stomach, but that didn’t mean that you turned away a stranger who was hungry. These people knew hw bad things were for them, and so they helped their neighbors. Nevertheless, during the Great Depression, suicide rates in the United States reached an all-time high, topping 22 suicides per 100,000 people. The living conditions were deplorable, and many people couldn’t take it. They felt that somehow they were at fault. still, for the majority of Americans, that didn’t mean that they gave up. Neighbor looked out for neighbor, and families came together to support each other, and while the effects of the Great Depression lasted for 12 years, this too passed, and the nation healed again.

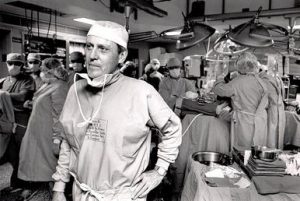

These days, organ transplants are a fairly common event. It’s not that everyone is having them, but that many people who need one get it. Years ago, something like a failing liver was an instant death sentence. The doctors would try to find a way to heal the liver, but they knew that it was not likely to happen. I know that it was heartbreaking for the doctors, who became doctors to save lives, not to lose them.

These days, organ transplants are a fairly common event. It’s not that everyone is having them, but that many people who need one get it. Years ago, something like a failing liver was an instant death sentence. The doctors would try to find a way to heal the liver, but they knew that it was not likely to happen. I know that it was heartbreaking for the doctors, who became doctors to save lives, not to lose them.

The real game changer came in 1963, when Dr Thomas E Starzl of Denver, Colorado, performed the first successful liver transplant in history. The patient was a 48 year old man. Unfortunately, he only lived for 22 day, but in those 22 days, a door was opened. Yes, there were problems, and the patient died, but he also lived…with a liver that wasn’t originally his. That was a huge step in the transplant game, and because of that step, Starzl became known as “the father of modern transplantation.”

Between March 1 and October 4, 1963, Starzl attempted 5 human liver replacements. The first patient bled to death during the operation. The other 4 died after 6.5 to 23 days. The autopsies didn’t show rejection, but rather that the patients died of site infections. During this time, there were also single attempts at transplant,  Francis D. Moore in September 1963 in Boston, and Demirleau in January 1964 in Paris. None were considered successful, but as I said. I would disagree, because while the patients died, they also lived. At this point, liver transplants on humans stopped until the summer of 1967. The operation was thought to be too difficult to ever be tried again, but Starzl refused to give up, and in 1967, he performed the first successful human liver transplant, at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center. This one would be even be considered a success by Starzl. He had also performed the world’s first spleen transplant four months earlier in the same year. After that, transplants became everyday operations.

Francis D. Moore in September 1963 in Boston, and Demirleau in January 1964 in Paris. None were considered successful, but as I said. I would disagree, because while the patients died, they also lived. At this point, liver transplants on humans stopped until the summer of 1967. The operation was thought to be too difficult to ever be tried again, but Starzl refused to give up, and in 1967, he performed the first successful human liver transplant, at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center. This one would be even be considered a success by Starzl. He had also performed the world’s first spleen transplant four months earlier in the same year. After that, transplants became everyday operations.

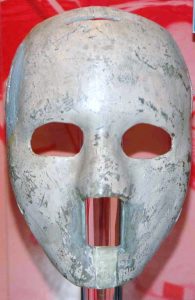

If you could see all of Terry Sawchuk’s wounds at once, his face would look like this one that was reproduced with makeup. In reality, Terry’s wounds have healed over the years, and the scars are not nearly as visible as the makeup reproduction portrays. Nevertheless, Sawchuk’s 16 years of playing goalie for the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey team in the years before the goalies wore safety equipment left their marks and took their toll on his body. Re-created here, by a professional make-up artist and a doctor, are some of the more than 400 stitches he had earned during 16 years in the National Hockey League. Terry Sawchuk’s face was bashed over and over, but not all at one time. The re-creation of his injuries was done to help show the extent of his injuries over a span of years. Sawchuk had sustained other injuries that were not shown here too…a slashed eyeball requiring three stitches, a 70% loss of function in his right arm because 60 bone chips were removed from his elbow, and a permanent “sway-back” that was caused by a continual bent-over posture during the games.

If you could see all of Terry Sawchuk’s wounds at once, his face would look like this one that was reproduced with makeup. In reality, Terry’s wounds have healed over the years, and the scars are not nearly as visible as the makeup reproduction portrays. Nevertheless, Sawchuk’s 16 years of playing goalie for the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey team in the years before the goalies wore safety equipment left their marks and took their toll on his body. Re-created here, by a professional make-up artist and a doctor, are some of the more than 400 stitches he had earned during 16 years in the National Hockey League. Terry Sawchuk’s face was bashed over and over, but not all at one time. The re-creation of his injuries was done to help show the extent of his injuries over a span of years. Sawchuk had sustained other injuries that were not shown here too…a slashed eyeball requiring three stitches, a 70% loss of function in his right arm because 60 bone chips were removed from his elbow, and a permanent “sway-back” that was caused by a continual bent-over posture during the games.

Many people were hurt playing sports in the years before safety equipment was used. For some of them, like Sawchuk, the equipment would not come in time to spare them from years of pain, and even disabilities. It was  a sad reality of many sports that everyone loves. The first goalie’s mask was a metal fencing mask donned in February 1927 by Queen’s University netminder Elizabeth Graham, mainly to protect her teeth. In 1930, the first crude leather model of the mask, which was actually an American football “nose-guard” was worn by Clint Benedict to protect his broken nose. After recovering from the injury, he abandoned the mask, never wearing one again in his career. At the 1936 Winter Olympics, Teiji Honma wore a crude mask, similar to the one worn by baseball catchers. The mask was made of leather, and had a wire cage which protected the face, as well as Honma’s large circular glasses.

a sad reality of many sports that everyone loves. The first goalie’s mask was a metal fencing mask donned in February 1927 by Queen’s University netminder Elizabeth Graham, mainly to protect her teeth. In 1930, the first crude leather model of the mask, which was actually an American football “nose-guard” was worn by Clint Benedict to protect his broken nose. After recovering from the injury, he abandoned the mask, never wearing one again in his career. At the 1936 Winter Olympics, Teiji Honma wore a crude mask, similar to the one worn by baseball catchers. The mask was made of leather, and had a wire cage which protected the face, as well as Honma’s large circular glasses.

Finally, in 1959 goalies began wearing masks full-time. On November 1, 1959, in a game between the Montreal Canadiens and New York Rangers of the National Hockey League, Canadiens goaltender Jacques Plante was struck in the face by a shot from Andy Bathgate. He had previously worn a face mask in practice, but coach Toe Blake refused to allow him to wear it in a game. He thought it might inhibit his vision. After being stitched up, Plante gave Blake an ultimatum. He refused to go back out onto the ice without the mask. Blake agreed, not wanting to forfeit the game, because NHL teams did not have back-up goalies at the time. Plante went on a long unbeaten streak wearing the mask. That ended when he was asked to remove it for a game. After that particular loss, Plante resumed donning the mask for the remainder of his career. Plante was ridiculed when he introduced the mask into the game. People questioned his dedication and bravery. In response, Plante made an analogy to a person skydiving without a parachute. Although Plante faced some

teasing, the face-hugging fiberglass goalie’s mask soon became the standard. Since the invention of the fiberglass hockey mask, professional goalies no longer play without a mask. The last goalie to play without a mask was Andy Brown, who played his last NHL game in 1974. He would then go to the Indianapolis Racers of the WHA and play without a mask till his retirement in 1977. So much has been learned about playing without protective gear since those days, but for the people who played before all that information, it came at a heavy price.

teasing, the face-hugging fiberglass goalie’s mask soon became the standard. Since the invention of the fiberglass hockey mask, professional goalies no longer play without a mask. The last goalie to play without a mask was Andy Brown, who played his last NHL game in 1974. He would then go to the Indianapolis Racers of the WHA and play without a mask till his retirement in 1977. So much has been learned about playing without protective gear since those days, but for the people who played before all that information, it came at a heavy price.

I find it very sad to think that if a person had some ailments or injuries in this day and age, they would likely have lived through the episode, but in days gone by, and for President McKinley, that was not to be the case.

I find it very sad to think that if a person had some ailments or injuries in this day and age, they would likely have lived through the episode, but in days gone by, and for President McKinley, that was not to be the case.

On September 6, 1901, while standing in a receiving line at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, McKinley was approached by Leon Czolgosz, a Polish-American anarchist carrying a concealed .32 revolver in a handkerchief. Czolgosz shot McKinley twice at close range. One bullet deflected off a suit button, but the other entered his stomach, passed through the kidneys, and lodged in his back. When he was operated on, doctors failed to find the bullet. That in and of itself was a very  serious situation, but I believe it would have been survivable. Unfortunately for President McKinley, the doctors of that time had few, if any antibiotics to fight infection, and gangrene soon spread throughout the president’s body. McKinley died eight days later, on September 14, 1901. Czolgosz was convicted is of murder and executed soon after the shooting.

serious situation, but I believe it would have been survivable. Unfortunately for President McKinley, the doctors of that time had few, if any antibiotics to fight infection, and gangrene soon spread throughout the president’s body. McKinley died eight days later, on September 14, 1901. Czolgosz was convicted is of murder and executed soon after the shooting.

These days, there have been a number of people who have had injuries far more grave than President McKinley had, and yet they have come through with flying colors. I think it is irrelevant what a person’s politics are or whether you think President McKinley was a good president or a bad president, because this really isn’t about politics at all. The reality is that this man died largely because of a lack of modern medicines that could  have easily cured the gangrene he had from the shooting, or in most cases, prevented it all together.

have easily cured the gangrene he had from the shooting, or in most cases, prevented it all together.

None of us likes to pay for the cost of some of the life-saving drugs that have been developed, but it is partly that cost that helps to pay for the research that goes into these new medicines. Whether we pay for them by donations before development or cost after development, really makes no difference. I know many people think that the drug companies gouge the patient, and I suppose that could be true to an extent, but which one of us has what it takes to find a medicine that cures some of the diseases we can cure today, that were a death sentence in years gone by?

The more I write, the more connected I feel to my Great Aunt Bertha Schumacher Hallgren. I have a feeling that we both used writing for much the same reason…a release of the creative side of ourselves when much of our lives were spent taking care of others. Caregiving is something that is very much an exact science. You have to give the right medicines at the right times, and caring for sick and wounded bodies takes precision and proper methods. There is no room for creativity…other than in the use of items at your disposal to make your job easier, whether it be physical items or the use of your mental abilities to work around a difficult moment in the care of a patient who isn’t ready to give over their independence to someone else, after so many years of being their own person. A caregiver has to follow the instructions of the doctors to the letter in order to insure the improvement and continued health of the patient. And Bertha was a caregiver for many more years than I have been. She knew what it took, and what must be sacrificed.

The more I write, the more connected I feel to my Great Aunt Bertha Schumacher Hallgren. I have a feeling that we both used writing for much the same reason…a release of the creative side of ourselves when much of our lives were spent taking care of others. Caregiving is something that is very much an exact science. You have to give the right medicines at the right times, and caring for sick and wounded bodies takes precision and proper methods. There is no room for creativity…other than in the use of items at your disposal to make your job easier, whether it be physical items or the use of your mental abilities to work around a difficult moment in the care of a patient who isn’t ready to give over their independence to someone else, after so many years of being their own person. A caregiver has to follow the instructions of the doctors to the letter in order to insure the improvement and continued health of the patient. And Bertha was a caregiver for many more years than I have been. She knew what it took, and what must be sacrificed.

Bertha quoted Charles Lamb, who in 1890 wrote “I love to lose myself in other men’s minds.” It might seem a strange thought, to want to get lost in the thoughts of another person, but sometimes their thoughts are so interesting that it is a desirable place to be. Must of us lose ourselves in another man’s mind periodically. Every time you read a good book, your mind pictures the thoughts and images created by the writer. You can’t help yourself really. It’s just how our minds are wired to work.

I have read Aunt Bertha’s journal several times, but it just never gets old. It seems like every time I read it, I discover some new story, whether it is written in the words or simply exists between the lines. Much of what a writer is like can be found living between the lines of the words they write. That is where their feelings live in their writing. Although I don’t recall ever having the opportunity to meet Aunt Bertha, I feel like I know her well. She has poured her heart and soul into her writing. She has been brutally honest about herself. She doesn’t leave out her shortcomings, but puts them into the stories, regardless of how they might make the reader feel about the kind of person she was. Her objective is not to paint herself as a perfect person, but rather to reveal to the reader the true person she was.

I think many writers would not have the courage to put on paper exactly how they were as a child, worker, caregiver, or person, because they don’t want to show the reader the negative thoughts, or mistakes they have made in their lives. The reality, nevertheless, is that none of us are perfect, but rather human. While Aunt Bertha was not perfect, I truly like the person she was. She reminds me a little bit of myself, and yet inspires me to try to be better than I once was. In her mind, she knows the kind of person she wants to be, and while she failed sometimes, she never quit trying. I find that her mind is truly a good one to lose myself in sometimes.

Lately, I have been looking in Ancestry.com, at immigration records for many of my ancestors. As I looked at the different ships they sailed on and the different locations they came from, I began to wonder about what it was really like to immigrate back them. I decided to do some research on that subject, and I was amazed at some of what I found.

Lately, I have been looking in Ancestry.com, at immigration records for many of my ancestors. As I looked at the different ships they sailed on and the different locations they came from, I began to wonder about what it was really like to immigrate back them. I decided to do some research on that subject, and I was amazed at some of what I found.

Of course, the biggest obstacle they faced was the cost…especially for a family. What doesn’t sound like much to us today, was really a lot of money back in the 1800s, and before. My great grandfather, Carl Schuhmacher spent seven years saving the $50.00 that it cost for one person to go. Many times, the whole family would work to send one person over so they could see if the opportunities were really there, and then that person would work t pay for the rest of the family to come.

For people who had to travel in steerage class, the journey was going to be a rough one. There was no limit to the number of steerage tickets sold, and the cost was usually $30.00 per ticket, which tells me that maybe my great grandfather had not traveled in steerage class…which is a relief to me after what I have read. Since there was no limit to the steerage tickets sold, the people were packed into the steerage area like cattle. The cost to feed each one was about sixty cents a day, so they could potentially make a net profit of $45,000 to $60,000 for each crossing. This was money made at the expense of the health, welfare, and even lives of those steerage passengers…a fact that I find shocking to say the least!!

Even when the immigrant wasn’t in steerage, the rough weather often made everyone sick. I don’t think that ships back then had some of the stabilizing features ships have today, and since they were smaller, they were probably tossed around more. Not good if you get sea sick…or even if you normally don’t.

Immigrants were told to be at the docks a day ahead of the departure date, because they had to be examined by American doctors before they were allowed to board the ship. I have no idea where they waited if they didn’t get examined the day before they sailed. I also have to wonder if they had to be examined again when they arrived here, because so many of them were sick on the ship that I would still think they brought disease to America.

Arrival in America didn’t necessarily mean they were set either. Because of language differences and strange sounding names, they were often subject to verbal abuse and discrimination. To fit in they would need to learn  English…something I do agree with, although I don’t agree with discrimination or verbal abuse…or any other kind of abuse. I think they needed someone to teach them, without belittling them. Most wanted to fit in, but didn’t know how to learn English, or simply didn’t have a way to learn it.

English…something I do agree with, although I don’t agree with discrimination or verbal abuse…or any other kind of abuse. I think they needed someone to teach them, without belittling them. Most wanted to fit in, but didn’t know how to learn English, or simply didn’t have a way to learn it.

Any time you make a decision to move to another country, it is a life changing decision, but in those days, it was a much bigger change than it is these days. Had it not been for necessity, due to famine and poverty in their ow country, I have to wonder just how many people would have taken the risk.

The Noyes side of Bob’s family was a family of prominence. The American side of the family begins with the Reverend William Noyes who was born in England in 1568. While William remained in England all his life, two of his children and a distant cousin left England and immigrated to America, settling in the Massachusetts area. The occupations included ministers of the Gospel, doctors, and commissioned army officers. One interesting fact is that in nearly every generation, there were two siblings who married siblings from another family. I have seen this is many families, including my own, and it makes me wonder if part of the reason is that there were fewer people around with children of suitable age to marry the children of a family. This might have been the case, especially when families began to move out west. In the history of the Noyes family that points out these siblings marrying siblings of another family, I find that Dr James III married Ann Sanford, who was the daughter of Governor Peleg and Mary Sanford, and his brother, Colonel Thomas Noyes married Ann’s sister, Elizabeth Sanford. While this is a bit unusual, it does happen, and there is nothing wrong with it. The fact that it happened about once a generation is a bit more unusual, but I guess it could be that these siblings had similar taste in mates.

The Noyes side of Bob’s family was a family of prominence. The American side of the family begins with the Reverend William Noyes who was born in England in 1568. While William remained in England all his life, two of his children and a distant cousin left England and immigrated to America, settling in the Massachusetts area. The occupations included ministers of the Gospel, doctors, and commissioned army officers. One interesting fact is that in nearly every generation, there were two siblings who married siblings from another family. I have seen this is many families, including my own, and it makes me wonder if part of the reason is that there were fewer people around with children of suitable age to marry the children of a family. This might have been the case, especially when families began to move out west. In the history of the Noyes family that points out these siblings marrying siblings of another family, I find that Dr James III married Ann Sanford, who was the daughter of Governor Peleg and Mary Sanford, and his brother, Colonel Thomas Noyes married Ann’s sister, Elizabeth Sanford. While this is a bit unusual, it does happen, and there is nothing wrong with it. The fact that it happened about once a generation is a bit more unusual, but I guess it could be that these siblings had similar taste in mates.

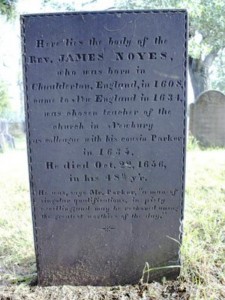

One of the main reasons that some of the Noyes men moved to American is the same as the reason that many of the first settlers came to America…religious differences with the Church of England. The United States has always been a country that prides itself of personal and religious freedoms. James, who is my husband, Bob’s 7th great grandfather, and who was born in England in 1608, married Sarah Brown, and they immigrated to America, and shortly thereafter, he became one of the founders of Newbury, Massachusetts, where he and his wife settled. He was a minister of the Gospel there for twenty years, and was very well liked in the area. His memory is still precious there to this day.

The Reverend James II, who is my husband, Bob’s 6th great grandfather, and who is the second son of James I and Sarah, followed in the footsteps of his dad, as a minister of the Gospel. His biggest claim to fame is that he bore an active part in the founding of Yale College, and his name was the first of “Ten of the principal ministers in the colony, nominated and agreed upon by general consent both of the ministers and people to stand as Trustees or Undertakers, to found, erect and govern a college.” He was selected to be one of the first trustees and founders of Yale. By this time he was an old man and lived in a remote part of the county, but his influence was considered essential to the undertaking. During his ministry he is noted to have baptized one thousand one hundred and seventy-six persons.

Deacon Noyes, who is the fifth son of Reverend James Noyes II, and Bob’s 5th great grandfather, married Dorothy Stanton, which is part of the  reason I have to wonder in there is a connection between my dad’s half brother’s mother, Edna Stanton, and Bob’s family through Dorothy Stanton. My grandfather, Allen Spencer, and Edna Stanton Spencer had a daughter, who they named Dorothy, and that along with the name Stanton, gives one reason to wonder. I am encouraged a little bit in my search, in that the Noyes family kept good family records. I hope this will be a useful when it comes to a possible connection between the Stantons of the Noyes family, and the Stanton of the Spencer family. Whatever happens, I find that the Noyes family were honorable people of distinction. They were active in their communities, loved and respected, making them a great American family.

reason I have to wonder in there is a connection between my dad’s half brother’s mother, Edna Stanton, and Bob’s family through Dorothy Stanton. My grandfather, Allen Spencer, and Edna Stanton Spencer had a daughter, who they named Dorothy, and that along with the name Stanton, gives one reason to wonder. I am encouraged a little bit in my search, in that the Noyes family kept good family records. I hope this will be a useful when it comes to a possible connection between the Stantons of the Noyes family, and the Stanton of the Spencer family. Whatever happens, I find that the Noyes family were honorable people of distinction. They were active in their communities, loved and respected, making them a great American family.