darkness

Most of us think very little about piloting a plane. We leave that to the professionals, but how did they get to be professionals? How did they learn all the techniques that they now use every day? Of course, that is a story that is far to long to write here, but suffice it to say that there was a lot of trial and error, a lot of visionaries, and a lot of test pilots who were willing to lay it on the line for progress. Test pilots suffered everything from failure to death in their quest for victory. Eventually they would go on to pave the way for so much innovation, that today, air travel is a commonplace thing, available to almost everyone.

Most of us think very little about piloting a plane. We leave that to the professionals, but how did they get to be professionals? How did they learn all the techniques that they now use every day? Of course, that is a story that is far to long to write here, but suffice it to say that there was a lot of trial and error, a lot of visionaries, and a lot of test pilots who were willing to lay it on the line for progress. Test pilots suffered everything from failure to death in their quest for victory. Eventually they would go on to pave the way for so much innovation, that today, air travel is a commonplace thing, available to almost everyone.

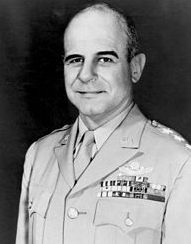

One such innovator, was Jimmy Doolittle. Prior to 1929, planes either had to be rerouted, or not fly in bad weather or limited visibility, but Doolittle was sure that there was a way to fly blind…and land safely. Now he just had to prove it. Until 1929, the only way to fly or land was by sight…known as VFR (Visual Flight Rules). These days pilots know that even if they can’t see, they can still fly safely using the instruments…known as IFR (Instrument Flight Rules).

I’m sure that someone had the idea in their head, that such a thing was possible, with no way to figure it out, but Doolittle was about to make his most important contribution to aeronautical technology…the development of instrument flying. Doolittle realized that true operational freedom in the air could not be achieved unless pilots developed the ability to control and navigate aircraft in flight, from takeoff to landing, regardless of the range of vision from the cockpit. It was an amazing unheard of idea. Doolittle believed that a pilot could be trained to use instruments to fly through fog, clouds, precipitation of all forms, darkness, or any other type of poor visibility. He also believed that the plane could be landed safely even if the pilot’s motion sense was impared. At that time, the ability to control aircraft was partly about getting beyond the motion sense capability of the pilot. You see, sometimes pilots could become seriously disoriented without the visual cues from outside the cockpit.

On this day, September 25, 1929, Doolittle would prove his theory, that if a pilot would “trust his instruments” and not his senses, he could safely take off, fly, and land, even if he could not see. Flying blind became a reality when Doolittle took off from and returned to Mitchel Field that September day. He had assisted in the development of fog flying equipment, helped develop, and was then the first to test, the now universally used artificial horizon and directional gyroscope. Of course, the flight made big news and Doolittle was given the Harmon Trophy for conducting the experiment.