cuban missile crisis

Each American presidency is marked by a defining moment, an event that encapsulates its tenure. For John F. Kennedy’s presidency, the Cuban Missile Crisis stood as that pivotal event. The most intense phase of the crisis, often referred to as the “13 Days,” spanned from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy was informed of the Soviet missile sites being built in Cuba, to October 28, 1962, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev declared the dismantling of the missiles. On October 22, 1962, when it came time to tell the American people about the situation, President Kennedy revealed in a televised address of profound significance, that American spy planes had detected Soviet missile bases in Cuba. This represented a very dangerous situation for the United States. The missile sites were still under construction, but they were close to completion, and they contained medium-range missiles with the capacity to hit several major US cities, including Washington DC.

Each American presidency is marked by a defining moment, an event that encapsulates its tenure. For John F. Kennedy’s presidency, the Cuban Missile Crisis stood as that pivotal event. The most intense phase of the crisis, often referred to as the “13 Days,” spanned from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy was informed of the Soviet missile sites being built in Cuba, to October 28, 1962, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev declared the dismantling of the missiles. On October 22, 1962, when it came time to tell the American people about the situation, President Kennedy revealed in a televised address of profound significance, that American spy planes had detected Soviet missile bases in Cuba. This represented a very dangerous situation for the United States. The missile sites were still under construction, but they were close to completion, and they contained medium-range missiles with the capacity to hit several major US cities, including Washington DC.

Kennedy declared he was imposing a naval “quarantine” on Cuba to block Soviet ships from delivering additional offensive weapons to the island. He stated that the United States would not accept the current missile sites’ presence. The president emphasized that America was prepared to take military action to eliminate what he described as a “secretive, irresponsible, and provocative threat to global peace.”

The Cuban Missile Crisis, as it became known, began on October 14, 1962, when US intelligence, analyzing data from a U-2 spy plane, discovered that the Soviet Union was constructing medium-range missile sites in Cuba. The following day, President Kennedy convened a secret emergency meeting with his top military, political, and diplomatic advisers to address the grave situation. This group came to be known as ExComm, an abbreviation for Executive Committee. Opting against a surgical air strike on the missile sites, ExComm instead chose a naval blockade and demanded the dismantling and removal of the missiles. It was then, on the evening of October 22, that President Kennedy disclosed his decision on national television. Tensions continued to mount over the ensuing six days, to a critical point, and placing the world on the edge of nuclear warfare between the two superpowers.

On October 23, the United States initiated a naval “quarantine” of Cuba. However, President Kennedy opted to allow Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev additional time to contemplate the US maneuver by moving the quarantine line back 500 miles. By October 24, Soviet vessels bound for Cuba, capable of transporting military cargo, seemed to have decelerated, changed course, or turned around as they neared the quarantine zone, except for one ship…the tanker Bucharest. Following appeals from over 40 nonaligned countries, UN Secretary-General U Thant made private overtures to Kennedy and Khrushchev, imploring their administrations to “avoid any actions that might worsen the situation and pose a risk of war.” Under orders from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, United States armed forces escalated to DEFCON 2, the most critical military readiness level ever achieved in the postwar period, while commanders readied for an all-out conflict with the Soviet Union.

On October 25, the aircraft carrier USS Essex and the destroyer USS Gearing tried to intercept the Soviet tanker Bucharest as it breached the US quarantine of Cuba. The Soviet vessel did not comply, but the US Navy refrained from taking it by force, judging that it was unlikely to be carrying offensive weapons. On October 26, Kennedy was informed that construction on the missile bases continued unabated, and ExComm contemplated a US invasion of Cuba. The Soviets apparently felt the tension of their actions, because on that same day, they offered a deal to resolve the crisis: they would dismantle the missile bases in return for a United States guarantee not to invade Cuba.

The following day, Khrushchev escalated the situation by publicly demanding the removal of US missile bases in Turkey, influenced by Soviet military leaders. As Kennedy and his advisors deliberated over this perilous shift in negotiations, a U-2 spy plane was downed over Cuba, resulting in the death of its pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson. It looked like thing might have reached the boiling point, but despite the Pentagon’s dismay, Kennedy prohibited any military response unless further surveillance aircraft were targeted over Cuba. To alleviate the intensifying crisis, Kennedy and his team decided to dismantle the US missile installations in Turkey at a subsequent time, to avoid provoking Turkey, who was an essential NATO ally.

On October 28, Khrushchev declared his government’s decision to dismantle and remove all offensive Soviet weapons from Cuba. Following the broadcast of this public announcement on Radio Moscow, the USSR affirmed its readiness to adopt the resolution secretly suggested by the Americans the previous day. That afternoon, Soviet technicians started dismantling the missile sites, averting the imminent threat of nuclear war. The Cuban Missile Crisis had effectively ended. In November, Kennedy lifted the blockade, and by year’s end, all offensive missiles were removed from Cuba. Later, the United States discreetly withdrew its missiles from Turkey.

At the time, the Cuban Missile Crisis appeared to be a definitive triumph for the United States. In this, Cuba gained a heightened sense of security following the crisis. The withdrawal of obsolete Jupiter missiles from Turkey did not negatively impact the United States’ nuclear strategy. Nevertheless, the crisis spurred the USSR, feeling humiliated, to initiate a substantial nuclear arms expansion. By the 1970s, the Soviet Union had achieved nuclear parity with the United States and developed intercontinental ballistic missiles with the capability to target any city within the United States.

The presidents that followed Kennedy upheld his promise to refrain from invading Cuba, and the relationship with the communist nation, located a mere 80 miles off the coast of Florida, continued to challenge United States foreign policy for over half a century. Finally, in 2015, representatives from both countries declared the official normalization of United States-Cuba relations, encompassing the relaxation of travel bans and the establishment of embassies and diplomatic offices in each nation.

For Kennedy, this pivotal moment in his administration showcased his ability to manage a high-stakes international crisis. His decision to implement a naval blockade and negotiate with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev helped avoid a potential nuclear war. It also demonstrated his leadership and diplomatic skills, as he balanced military readiness with diplomatic negotiations, which ultimately led to the removal of Soviet missiles from Cuba. The successful resolution of the crisis significantly boosted Kennedy’s public image, portraying him as a strong and capable leader who could protect the United States from external threats. The crisis was a defining moment in the Cold War, highlighting the intense rivalry between the United States and the

Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it also led to the establishment of a direct communication line between Washington and Moscow, known as the “hotline,” to prevent future crises. In summary, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a defining event that not only tested Kennedy’s presidency, but it also shaped his legacy as a leader who could navigate the complexities of international relations during one of the most dangerous periods of the Cold War.

Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it also led to the establishment of a direct communication line between Washington and Moscow, known as the “hotline,” to prevent future crises. In summary, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a defining event that not only tested Kennedy’s presidency, but it also shaped his legacy as a leader who could navigate the complexities of international relations during one of the most dangerous periods of the Cold War.

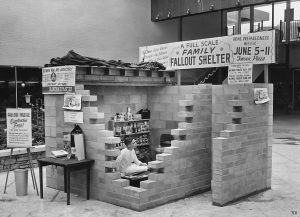

For anyone alive and of an age to remember it, the 1950s and 1960s brought with them a strange new reality. I can’t say that I fully understood it all at that time, but I remember our school having a “Fallout Shelter.” They were also called a “Bomb Shelter” in some places, and the purpose was to protect the population from exposure to the fallout from a nuclear explosion. I suppose that if I had understood more about what these were, I might have been scared, but I just remember thinking it a strange idea, and highly unlikely. It did occur to me that if a bomb to explode, it would be unlikely that we would all have time to get to the school for protection.

For anyone alive and of an age to remember it, the 1950s and 1960s brought with them a strange new reality. I can’t say that I fully understood it all at that time, but I remember our school having a “Fallout Shelter.” They were also called a “Bomb Shelter” in some places, and the purpose was to protect the population from exposure to the fallout from a nuclear explosion. I suppose that if I had understood more about what these were, I might have been scared, but I just remember thinking it a strange idea, and highly unlikely. It did occur to me that if a bomb to explode, it would be unlikely that we would all have time to get to the school for protection.

Apparently, President John F. Kennedy, agreed with me on that thought, because, when he was speaking on civil defense on October 6, 1961, he advised American families to build bomb shelters to protect them from atomic fallout in the event of a nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union. We were, after all, in the middle of the Cold War, and neither side really knew if the other side would decide that they needed to start that latest, deadly type of war with the other side. Looking back, many people aren’t sure that a home-made bomb shelter would really be able to protect the occupants from the fallout of an atomic bomb. No one can really say for sure that the government-built shelters in schools and churches could either, in retrospect.

Still, prudent minds assumed that something needed to be done. Kennedy also assured the public that the United States civil defense program would soon begin providing such protection for every American. What seemed like science fiction, became a grim possibility just one year later, when true to Kennedy’s concerns, the world hovered on the brink of full-scale nuclear war when the Cuban Missile Crisis erupted over placement of nuclear missiles in Cuba by the USSR. Of course, panic ensues. The crisis lasted for 13 days, but some Americans prepared for nuclear war by buying up canned goods and completing last-minute work on their backyard bomb shelters. In the end, of course, it all ended without. After several days of tense negotiations, Kennedy and Khrushchev reached an agreement. Publicly, the Soviets would dismantle their offensive weapons in Cuba and return them to the Soviet Union, subject to United Nations verification, in exchange for a US public

declaration and agreement to avoid invading Cuba again. The Kennedy administration had been publicly embarrassed by the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961, which had been launched under President John F Kennedy by CIA-trained forces of Cuban exiles. Afterward, former President Dwight Eisenhower told Kennedy that “the failure of the Bay of Pigs will embolden the Soviets to do something that they would otherwise not do.” He was right, but for now, disaster was averted.

declaration and agreement to avoid invading Cuba again. The Kennedy administration had been publicly embarrassed by the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961, which had been launched under President John F Kennedy by CIA-trained forces of Cuban exiles. Afterward, former President Dwight Eisenhower told Kennedy that “the failure of the Bay of Pigs will embolden the Soviets to do something that they would otherwise not do.” He was right, but for now, disaster was averted.

The United States and Russia have long been frenemies, truth be told, but in October of 1962, no one would have called them that. The Cuban Missile Crisis brought the two super powers to the brink of a nuclear conflict. As we all know, that would have been devastating for the inhabitants of the earth, and in the end, both countries agreed that we could not let things escalate to that level again. In June of 1963, American and Russian representatives agreed to establish a “hot line” between Moscow and Washington DC. The idea was to speed communication between the two governments to prevent an accidental war.

The United States and Russia have long been frenemies, truth be told, but in October of 1962, no one would have called them that. The Cuban Missile Crisis brought the two super powers to the brink of a nuclear conflict. As we all know, that would have been devastating for the inhabitants of the earth, and in the end, both countries agreed that we could not let things escalate to that level again. In June of 1963, American and Russian representatives agreed to establish a “hot line” between Moscow and Washington DC. The idea was to speed communication between the two governments to prevent an accidental war.

By August of 1963, the system was ready to be tested. American teletype machines were installed in the Kremlin and at the Pentagon. Many people have thought that the machine at the Pentagon was actually in the White House, but that is incorrect. The two nations exchanged  encoding devises so that they could decipher the messages. This would allow the two nations to message each other in a matter of minutes. That would be somewhat slow in today’s high tech world of cell phones and texting, but in those days, it was state of the art. Once received, the message would have to be deciphered, which did slow things down a bit, but again, at that time, it was state of the art. The two teletype machines were connected by a 10,000 mile long cable with “scramblers” along the way to ensure that the messages could not be intercepted by unauthorized personnel.

encoding devises so that they could decipher the messages. This would allow the two nations to message each other in a matter of minutes. That would be somewhat slow in today’s high tech world of cell phones and texting, but in those days, it was state of the art. Once received, the message would have to be deciphered, which did slow things down a bit, but again, at that time, it was state of the art. The two teletype machines were connected by a 10,000 mile long cable with “scramblers” along the way to ensure that the messages could not be intercepted by unauthorized personnel.

On August 30, the United States sent its first message to the Soviet Union over the hot line: “The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog’s back 1234567890.” The message was chosen because it used every letter and number key on the teletype machine in order to see that each was in working order. Moscow returned a message in Russian indicating that every key had worked properly. In the end, the hot line was never needed  to prevent war, but instead has become a novelty item, used as a prop in movies about nuclear disaster. Fail Safe and Dr Strangelove were two movies that utilized the machines. The reality was that the two superpowers had come so close to mutual destruction back in 1962, that neither had much stomach for the proposed threat. They understood that communication was key in stopping a nuclear war. Of course, that has not stopped other nations from threatening to use nuclear weapons against other nations of the world. The Cold War ended a long time ago, but the “hot line” is still in operation between the two superpowers, and has since been supplemented by a direct secure telephone connection in 1999.

to prevent war, but instead has become a novelty item, used as a prop in movies about nuclear disaster. Fail Safe and Dr Strangelove were two movies that utilized the machines. The reality was that the two superpowers had come so close to mutual destruction back in 1962, that neither had much stomach for the proposed threat. They understood that communication was key in stopping a nuclear war. Of course, that has not stopped other nations from threatening to use nuclear weapons against other nations of the world. The Cold War ended a long time ago, but the “hot line” is still in operation between the two superpowers, and has since been supplemented by a direct secure telephone connection in 1999.