crimes

During five weeks in the fall of 1718, Charleston’s citizens observed thirteen trials involving fifty-eight men charged with piracy. Piracy was and is looked upon as a particularly heinous crime. Most of the documentation of the trials was done by clerks working feverously with quill and ink. Pirates were and are known for the viciousness of the crimes they commit. For them, it is not enough to steal the valuables from the boats to seize, they didn’t consider their attack complete until they had brutalized their victims. Piracy in that period included aggravated armed robbery, assault, murder, rape, and kidnapping at sea. It was a growing menace, and its presence at so close to colonial borders demanded and received the full attention of local authorities.

During five weeks in the fall of 1718, Charleston’s citizens observed thirteen trials involving fifty-eight men charged with piracy. Piracy was and is looked upon as a particularly heinous crime. Most of the documentation of the trials was done by clerks working feverously with quill and ink. Pirates were and are known for the viciousness of the crimes they commit. For them, it is not enough to steal the valuables from the boats to seize, they didn’t consider their attack complete until they had brutalized their victims. Piracy in that period included aggravated armed robbery, assault, murder, rape, and kidnapping at sea. It was a growing menace, and its presence at so close to colonial borders demanded and received the full attention of local authorities.

Between 1716 and 1718, several pirate ships frequently disrupted the maritime traffic entering and leaving Charleston’s port. These incidents significantly halted South  Carolina’s crucial sea trade. It was a serious matter and demanded serious repercussions. The pirate incursions were far more than mere nuisances or disruptions to trade. The fact was that they posed a real danger to the lives of many and threatened the political and economic foundations of the young colony. Unfortunately, with no local newspaper in Charleston until January 1732, there are no detailed accounts of the pirate activities of the 1710s. Finally, the provincial government of South Carolina, located in Charleston, engaged in discussions and formulated a collective response to the pirate threats of 1717 and 1718, but the particulars of their actions have mostly been lost to history. Consequently, we lack sufficient resources to fully narrate South Carolina’s brush with what our legislature once termed the “Pirates of the Bahamas.” Major Stede Bonnet’s crew consisted of Alexander Amand/Annand (from British Jamaica), Job ‘Bayley’ Baily (from London), Samuel Booth (from Charles Town), Robert Boyd (from Bath Town), Thomas Carman

Carolina’s crucial sea trade. It was a serious matter and demanded serious repercussions. The pirate incursions were far more than mere nuisances or disruptions to trade. The fact was that they posed a real danger to the lives of many and threatened the political and economic foundations of the young colony. Unfortunately, with no local newspaper in Charleston until January 1732, there are no detailed accounts of the pirate activities of the 1710s. Finally, the provincial government of South Carolina, located in Charleston, engaged in discussions and formulated a collective response to the pirate threats of 1717 and 1718, but the particulars of their actions have mostly been lost to history. Consequently, we lack sufficient resources to fully narrate South Carolina’s brush with what our legislature once termed the “Pirates of the Bahamas.” Major Stede Bonnet’s crew consisted of Alexander Amand/Annand (from British Jamaica), Job ‘Bayley’ Baily (from London), Samuel Booth (from Charles Town), Robert Boyd (from Bath Town), Thomas Carman  (from Maidstone, Kent), and George Dunkin (from Glasgow), to name a few, were considered particularly vicious, and their punishments would need to be vicious as well.

(from Maidstone, Kent), and George Dunkin (from Glasgow), to name a few, were considered particularly vicious, and their punishments would need to be vicious as well.

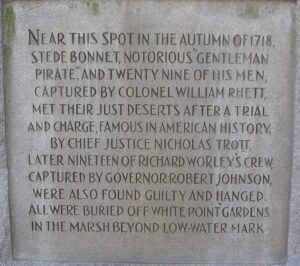

Following the trials and guilty verdicts, Major Stede Bonnet and his crew of 29 men were hanged on November 8, 1718, at White Point, Charleston, South Carolina. It had been decided that hanging just wasn’t bad enough for the crimes these men committed. I’m sure they thought long and hard about how they could show the same viciousness to these men, that they had shown to their victims. Finally, they came up with the perfect final punishment. Following their hanging, these men were buried in the marsh below the low watermark.

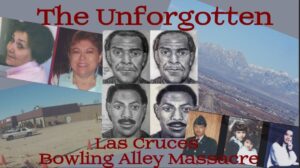

Evil can be just around the corner, and sadly, sometimes, the evil doers walk away without being punished for their crimes. On the morning of February 10, 1990, the staff at Las Cruces Bowl were busy getting ready for the Saturday bowling crowd, when two armed men walked in through an unlocked door. The men were there to rob the place. They could have worn masks, or they could have just robbed the place and fled the scene, but they had no intention of being caught, and that meant that they couldn’t leave witnesses.

Evil can be just around the corner, and sadly, sometimes, the evil doers walk away without being punished for their crimes. On the morning of February 10, 1990, the staff at Las Cruces Bowl were busy getting ready for the Saturday bowling crowd, when two armed men walked in through an unlocked door. The men were there to rob the place. They could have worn masks, or they could have just robbed the place and fled the scene, but they had no intention of being caught, and that meant that they couldn’t leave witnesses.

Stephanie C Senac, 34, who was the bowling alley manager, was in her office preparing to open the for the day. Her 12-year-old daughter Melissa Repass and Melissa’s 13-year-old friend Amy Houser were there to supervise the alley’s day care. The gunmen took them into the office, where they robbed them of a mere $4,000 to $5,000. As robberies go, it was practically nothing. When bowling alley mechanic Steven Teran came in with his two young daughters, Paula Holguin and Valerie Teran, they were totally unprepared for what faced them. Teran was unable to find a  babysitter for his daughters that day, so he had decided that he would drop them at the bowling alley daycare for the Melissa and Amy to watch. As the robbers took cash from the safe, the seven unfortunate people, including Teran and his daughters; cook Ida Holguin (no relation to Paula); manager Stephanie Senac, her daughter, and her daughter’s friend tried to be cooperative in the hope of making it out alive, but the men told them to get down on the ground. Then they shot all of the victims multiple times at close range, aiming mostly for their heads. When the shooting was over, they were still not satisfied with how things stood, so they set fire to some papers in the office of the bowling alley and left.

babysitter for his daughters that day, so he had decided that he would drop them at the bowling alley daycare for the Melissa and Amy to watch. As the robbers took cash from the safe, the seven unfortunate people, including Teran and his daughters; cook Ida Holguin (no relation to Paula); manager Stephanie Senac, her daughter, and her daughter’s friend tried to be cooperative in the hope of making it out alive, but the men told them to get down on the ground. Then they shot all of the victims multiple times at close range, aiming mostly for their heads. When the shooting was over, they were still not satisfied with how things stood, so they set fire to some papers in the office of the bowling alley and left.

Miraculously, Ida, Senac, and Melissa all survived. Melissa, despite being shot five times, was able to call 911. Unfortunately, the fire and subsequent efforts to put out the fire destroyed most of the evidence. In those days, forensics mostly involved fingerprints, which were in abundance in the bowling alley. DNA was not really as  developed at that time. Investigators were unable to discern which fingerprints were meaningful. There were witnesses, of course, who identified the suspects as two Hispanic men, in their 30s or 40s. Roadblocks were quickly set up by the police, to screen anyone leaving town. Still, the suspects were never found. Despite a frequent stream of tips, authorities are no closer to identifying and arresting the suspects today than they were 32 years ago…even with age enhanced pictures. The murders have been shown on multiple crime solving programs, including on Unsolved Mysteries two and a half months after the murders, and on America’s Most Wanted twice, once in November 2004 and again in March 2010. In the end, the crime also took the life of Stephanie Senac, who died in 1999…nine years later, due to complications from her injuries. The men got away with just $4,000 to $5,000, but the victims paid dearly.

developed at that time. Investigators were unable to discern which fingerprints were meaningful. There were witnesses, of course, who identified the suspects as two Hispanic men, in their 30s or 40s. Roadblocks were quickly set up by the police, to screen anyone leaving town. Still, the suspects were never found. Despite a frequent stream of tips, authorities are no closer to identifying and arresting the suspects today than they were 32 years ago…even with age enhanced pictures. The murders have been shown on multiple crime solving programs, including on Unsolved Mysteries two and a half months after the murders, and on America’s Most Wanted twice, once in November 2004 and again in March 2010. In the end, the crime also took the life of Stephanie Senac, who died in 1999…nine years later, due to complications from her injuries. The men got away with just $4,000 to $5,000, but the victims paid dearly.

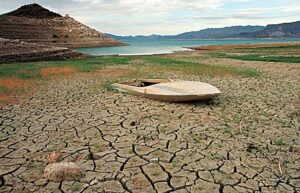

As a kid, I remember going to the Grand Canyon, Las Vegas, and Lake Mead. I particularly enjoyed Lake Mead, because the water was warm, unlike most lakes. At the time, and for many years afterward, I really didn’t know much about the lake, its origins, or its secrets. These days, I maybe know too much about its secrets. In fact, some of them are really creepy. Many lakes sport hidden ghost towns, underground ranches, and various sunken boats. There are probably more bodies in them that we know or want to think about too, but when a drought occurs and we find ourselves hearing about body after body being found in a lake that is close to one of the big mob-controlled areas of the nation, it makes you wonder exactly what happened here and just how many more bodies will surface. Well, in the case of Lake Mead, the answer is a total of five bodies…so far. Who knows how many more will surface.

As a kid, I remember going to the Grand Canyon, Las Vegas, and Lake Mead. I particularly enjoyed Lake Mead, because the water was warm, unlike most lakes. At the time, and for many years afterward, I really didn’t know much about the lake, its origins, or its secrets. These days, I maybe know too much about its secrets. In fact, some of them are really creepy. Many lakes sport hidden ghost towns, underground ranches, and various sunken boats. There are probably more bodies in them that we know or want to think about too, but when a drought occurs and we find ourselves hearing about body after body being found in a lake that is close to one of the big mob-controlled areas of the nation, it makes you wonder exactly what happened here and just how many more bodies will surface. Well, in the case of Lake Mead, the answer is a total of five bodies…so far. Who knows how many more will surface.

One body was found in a barrel, with a gun nearby, causing speculation of a mob killing, and possibly making people who might have been the perpetrators of mob murders…if they are still alive, to become a little nervous about their crimes being found out. Of course, the police aren’t telling us much, but it is said that the body in the barrel, discovered in May, had been shot in the head and after being stuffed in the barrel it was thrown overboard, in the hope that it would never be seen again. It was the type of killing that was classic mob style, or so we’ve been told in the movies. Las Vegas was, and maybe still is, a big mob crime city, and this type of killing was a trademark in the 1970s and 19802. So, it is entirely possible that the killer is still alive and could be brought to justice.

Shortly after the body in the barrel was found, another body surfaced, and then in July a third body was found. Days after the body in the barrel surfaced, another corpse was reported. A third was discovered in July. Now, the skeletal remains of two more people were found just this month in the Swim Beach area. It makes me

wonder how many more bodies will surface, if the drought continues and the lake level continues to drop. The lake level has dropped nearly 200 feet due to two decades of drought. Right now, the lake is very close to the level it was when it was originally filled after the building of Hoover Dam. I guess the old saying about the truth finding you out is true. the bodies, some long hidden, are coming out to tell of their demise.

wonder how many more bodies will surface, if the drought continues and the lake level continues to drop. The lake level has dropped nearly 200 feet due to two decades of drought. Right now, the lake is very close to the level it was when it was originally filled after the building of Hoover Dam. I guess the old saying about the truth finding you out is true. the bodies, some long hidden, are coming out to tell of their demise.

If you watch cop shows at all, you will know that if they are right, most crimes are solved…and in short order too. Of course, most of us realize that isn’t exactly the case. While I like to think most crimes are solved, there are still a great number of them that take years to solve and sometimes they remain unsolved indefinitely, if not forever. I suppose those would be the perfect crimes, but it is sad to think that a criminal gets away with a crime, no matter what it is. Such appears to be the case in the March 18, 1990 theft of 13 masterpieces worth $500 million from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The theft took place 26 years ago, and has never been solved, and the pieces are still missing.

If you watch cop shows at all, you will know that if they are right, most crimes are solved…and in short order too. Of course, most of us realize that isn’t exactly the case. While I like to think most crimes are solved, there are still a great number of them that take years to solve and sometimes they remain unsolved indefinitely, if not forever. I suppose those would be the perfect crimes, but it is sad to think that a criminal gets away with a crime, no matter what it is. Such appears to be the case in the March 18, 1990 theft of 13 masterpieces worth $500 million from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The theft took place 26 years ago, and has never been solved, and the pieces are still missing.

The museum was closed, and the night watchman, Richard Abath was on duty. Boston’s Saint Patrick’s Day revelers were finishing their last drinks before going home to sleep it off. Two police officers showed up at the door of the museum and rang the buzzer at 1:24 am. When the watchman opened the door, they informed him that they were there about the disturbance. The night watchman had been trained to first call Boston police headquarters to confirm officers’ names and badge numbers, but 23 year old Abath, who was an aspiring rock musician, and had given his notice days earlier, pressed a button to let the pair inside. The uniformed men ordered Abath to summon his fellow guard, 25 year old Randy Hestand, to the lobby.

When one of the officers said that Abath looked like someone they had a warrant out on, he broke protocol a second time when he left the desk, where the only panic button was, and obeyed their command to show them some identification. They handcuffed him and the arriving Hestand, who was filling in for a sick colleague and working the night shift for the first time. When both men were handcuffed, the men in police uniforms informed the guards, “This is a robbery, gentlemen.” Using duct tape, the intruders wrapped the guards like mummies, even covering Abath’s shoulder length curly hair and left them in the basement where they handcuffed Hestand to a sink and Abath to a workbench 40 yards away.

Then the thieves ransacked the museum, which had been a gift to the people of Boston in 1903, given by philanthropist, Isabella Stewart Gardner. Had they gone in and strategically taken valuable items, the robbery might have made sense, I suppose, but while they took $500 million worth of art, they also destroyed so much. They smashed gilded painting frames onto marble floors and sliced canvasses from their wooden backings. The robbers left an empty frame on the office chair of the museum’s security director and removed the recording tape from security system’s camera before departing 81 minutes after their arrival in a dark colored hatchback that disappeared into the night.

The two night watchmen were found the next morning, but the 13 pieces of artwork worth $500 million were gone. The most expensive piece was a painting titled “The Concert,” by Johannes Vermeer…one of only 36 known paintings by the Dutch master. The robbers got away with a sketch and two paintings by Rembrandt, including his only known seascape, “Storm on the Sea of Galilee.” They also took a Govaert Flinck landscape, Edouard Manet’s “Chez Tortoni,” five watercolors and sketches by Edgar Degas, a finial eagle that sat atop a Napoleonic flag that the thieves could not unscrew from the wall and an ancient Chinese vase. Strangely, the robbers had left untouched the museum’s most valuable painting, Titian’s “The Rape of Europa,” but an unwound coat hanger found near the candy machine suggested that they had also taken chocolate bars. It is suspected that the  men were working off of a specific list of items contracted for in advance by a black market collector outside of the United States. Latin American drug cartels, Irish Republican Army militants and even Vatican operatives were floated as suspects. Suspicion also fell on notorious Boston mobster James “Whitey” Bulger, but he was searching for whomever committed the audacious crime on his home “turf” as well so that he could exact a cut. The FBI investigation into Abath, who was the only person tracked by motion sensors in the gallery from which the Manet was swiped, did not yield any answers.

men were working off of a specific list of items contracted for in advance by a black market collector outside of the United States. Latin American drug cartels, Irish Republican Army militants and even Vatican operatives were floated as suspects. Suspicion also fell on notorious Boston mobster James “Whitey” Bulger, but he was searching for whomever committed the audacious crime on his home “turf” as well so that he could exact a cut. The FBI investigation into Abath, who was the only person tracked by motion sensors in the gallery from which the Manet was swiped, did not yield any answers.

The case has grown cold, and unless some kind of new clues surface, it will likely remain unsolved. The frames that held the stolen paintings remain empty to this day, and still hang in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, in the same places they were then…waiting for their lost painting to hopefully be returned someday. Time will tell.