coward

The term “coward” doesn’t normally bring with it thoughts of bravery in the face of danger, but perhaps it should…sometimes anyway. Charles Joseph Coward was born in Britain on January 30, 1905. I can’t say what his young life was like, and perhaps it was his parents who taught him to prove his name wrong, but I’m quite sure they were proud of just how well he proved that he was anything, but a coward. Coward joined the British Army in 1937 and served with the 8th Reserve Regimental Royal Artillery. By the time WWII started in 1939, he was a Quartermaster Battery Sergeant Major. They already saw something in him that disproved his name.

The term “coward” doesn’t normally bring with it thoughts of bravery in the face of danger, but perhaps it should…sometimes anyway. Charles Joseph Coward was born in Britain on January 30, 1905. I can’t say what his young life was like, and perhaps it was his parents who taught him to prove his name wrong, but I’m quite sure they were proud of just how well he proved that he was anything, but a coward. Coward joined the British Army in 1937 and served with the 8th Reserve Regimental Royal Artillery. By the time WWII started in 1939, he was a Quartermaster Battery Sergeant Major. They already saw something in him that disproved his name.

In World War II, Coward was fighting against the Nazis when the Germans assaulted the port of Calais on May 21, 1940, marking the start of the Siege of Calais. The German army drove the Allies back, and the British Expeditionary Force fled from France through the port of Dunkirk. Fortunately, most made it out in time…to fight the Germans another day. Unfortunately for Coward, he was not one of them, and he became a POW. He did have an advantage, however, in that he spoke German. He used his language skills to make seven escape attempts by passing himself off as a German soldier. One of the escape attempts worked. He was free, but he was injured, and was sent to a German Army field hospital. Coward kept up his German soldier act. After the German doctors had treated his wounds, he was awarded an Iron Cross for his bravery and suffering. Unfortunately, they realized their mistake pretty quickly. Coward was sent back to the POW camp where he earned a reputation for sabotage while on work details. Finally, he was sent to Poland…Auschwitz, to be precise…not to the death camp part of Auschwitz, but rather to the work camp part of it. Coward arrived at Auschwitz III (Monowitz), which was the working camp, in December 1943. The camp was located approximately five miles from Auschwitz II (Birkenau), which was the death camp. There he became a modern day “Hogan’s Hero,” although there was nothing funny about his situation, like there was in the television show. Coward spied on his captors and risked his life to save those he could. All that under the name of Coward.

IG Farben was a German chemical and pharmaceutical industry conglomerate. Its name was taken from Interessen-Gemeinschaft Farbenindustrie. IG Farben had acquired the patent to Zyklon B. It was originally used as an insecticide and by US immigration officials to delouse Mexican laborers. The Nazis had a different use for it…the extermination of Jews and other undesirables. Coward and between 1,200 and 1,400 other British POWs were kept at sub-camp E715. Their job was to run the liquid fuel plant which produced synthetic rubber. Coward, due to his German language skills worked as a Red Cross liaison officer, because Germany was still keeping up the pretense of honoring the Geneva Convention articles. He was allowed some measure of free movement within the camp, and even permitted to go to the nearby towns. In town, Coward saw trainloads of Jews arriving at the the extermination camp. Auschwitz III housed 10,000 Jews who were “allowed” to work. They were worked to the point of exhaustion and sickness. Given the brutality and deliberate starvation they did not last long. Coward simply couldn’t stand by and do nothing. The British POWs had access to Red Cross items, so Coward and the other prisoners set aside food and medicine to be smuggled to the Jewish section of their camp, to help as many as possible. Coward was allowed to send letters out, so he began writing to his friend…Mr. William Orange, a fictitious person. It was actually the code for the British War Office. In those letters, he explained what was happening in the camps, as well as the treatment and mass slaughter of Jews. One day, a letter was smuggled to him, asking for help. It came from Karel Sperber, a British ship’s doctor, but there was a problem…Sperber was being held in the Jewish section of Monowitz. So Coward exchanged clothes with an inmate and smuggled himself into the Jewish sector to try to find the doctor. Sadly, he failed, but he did see how Jews in the work camp were being treated. After the war, he was among those who testified at the IG Farben Trial in Nuremberg. He helped to have some of the company’s directors imprisoned, although only for a few years.

He wanted to help the Jews, but to pull it off, he needed two things…chocolate and corpses. It was a daring plan, but it worked. Coward gave the chocolate to the guards in exchange for the bodies of non-Jewish dead prisoners. Then, once their clothes and papers had been removed they were cremated. Jewish escapees put on the clothes and assumed the new, non-Jewish identities. With help from members of the Polish resistance, they were then smuggled out of the camp. As the number of those missing tallied with the number of those who were reported dead, neither Coward nor the bribed guards fell under any suspicion. It is estimated around 400

Jews were saved using Coward’s method. In January 1945 Soviet forces advanced deeper into Poland. As they made their way toward Auschwitz, Coward and the other POWs were forced to march to Bavaria in Germany. The prisoners were liberated by Allied forces en route, finally putting an end to the brutal nightmare. In 1963 Yad Vashem recognized Coward as one of the Righteous Among the Nations. He became known as the “Count of Auschwitz.” and a film was made of his exploits called “The Password is Courage.” I think he was a pretty brave man…for a Coward.

Jews were saved using Coward’s method. In January 1945 Soviet forces advanced deeper into Poland. As they made their way toward Auschwitz, Coward and the other POWs were forced to march to Bavaria in Germany. The prisoners were liberated by Allied forces en route, finally putting an end to the brutal nightmare. In 1963 Yad Vashem recognized Coward as one of the Righteous Among the Nations. He became known as the “Count of Auschwitz.” and a film was made of his exploits called “The Password is Courage.” I think he was a pretty brave man…for a Coward.

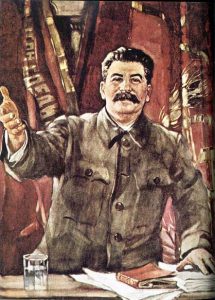

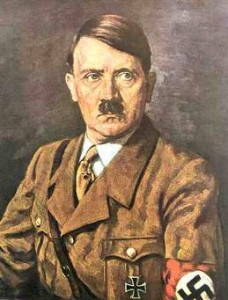

Imagine being in a country where being afraid is a crime. I’m sure you are wondering how that is possible…in any country, but I assure you, it is. That was the case on this day, July 27, 1943 in Russia. Joseph Stalin was the premier and dictator of Russia at that time in history, and Adolf Hitler was the dictator of Germany. The Germans were advancing into Russian territory, and Stalin was determined to stop them, no matter the cost.

Imagine being in a country where being afraid is a crime. I’m sure you are wondering how that is possible…in any country, but I assure you, it is. That was the case on this day, July 27, 1943 in Russia. Joseph Stalin was the premier and dictator of Russia at that time in history, and Adolf Hitler was the dictator of Germany. The Germans were advancing into Russian territory, and Stalin was determined to stop them, no matter the cost.

Hitler had become quite bold because of the early successes against Russia in his goal of taking Leningrad and Stalingrad. The attack on Stalingrad proved, however, that the Russians had superior manpower and it was an enormous drain on German resources and troop strength. The Germans were repulsed by a fierce Soviet fighting force, that had been reinforced with more men and materials. Hitler made the decision to turn his sights to Leningrad.

Stalin needed to make sure his force wouldn’t back down…no matter what happened. The motivation to stand  their ground needed to apply to both officers and civilians alike, or he was sure that Leningrad would be lost. That was when Stalin decided to put order number 227 into effect. So, what was order number 227? The order declared, “Panic makers and cowards must be liquidated on the spot. Not one step backward without orders from higher headquarters! Commanders…who abandon a position without an order from higher headquarters are traitors to the Fatherland.” Basically the order said that no one…not one person would be a coward. The order became known as the “not one step backward” order. The military personnel, as well as civilians were forced to fight for their city.

their ground needed to apply to both officers and civilians alike, or he was sure that Leningrad would be lost. That was when Stalin decided to put order number 227 into effect. So, what was order number 227? The order declared, “Panic makers and cowards must be liquidated on the spot. Not one step backward without orders from higher headquarters! Commanders…who abandon a position without an order from higher headquarters are traitors to the Fatherland.” Basically the order said that no one…not one person would be a coward. The order became known as the “not one step backward” order. The military personnel, as well as civilians were forced to fight for their city.

I think I can understand what Stalin was doing, but it seems such a drastic measure to take. Still, while some  people might fight the enemy to the end, others might decide that their city wasn’t worth their life. If the penalty for backing off was instant liquidation, then standing and fighting became the only way to have a chance at life. In my opinion, that as far as ways to gain loyalty goes, this was not the best of plans, but then forced loyalty seldom is. Still, one must never underestimate the love a patriot feels for their country. The “not one step backward” order was virtually unnecessary, in that on the day the order was issued, the Russian peasants and other supporters in the Leningrad region killed a German official, Adolf Beck, whose job was to send agricultural products from occupied Russia to Germany and to German troops. The Russian patriots also set fire to the granaries and barns in which the stash of agricultural products was stored before transport. A partisan pamphlet issued an order of its own: “Russians! Destroy the German landowners. Drive the Germans from the land of the Soviets!” I guess Stalin had misjudged his peoples’ loyalty.

people might fight the enemy to the end, others might decide that their city wasn’t worth their life. If the penalty for backing off was instant liquidation, then standing and fighting became the only way to have a chance at life. In my opinion, that as far as ways to gain loyalty goes, this was not the best of plans, but then forced loyalty seldom is. Still, one must never underestimate the love a patriot feels for their country. The “not one step backward” order was virtually unnecessary, in that on the day the order was issued, the Russian peasants and other supporters in the Leningrad region killed a German official, Adolf Beck, whose job was to send agricultural products from occupied Russia to Germany and to German troops. The Russian patriots also set fire to the granaries and barns in which the stash of agricultural products was stored before transport. A partisan pamphlet issued an order of its own: “Russians! Destroy the German landowners. Drive the Germans from the land of the Soviets!” I guess Stalin had misjudged his peoples’ loyalty.