corruption

As sometimes happens, children grow up and start hanging out with the wrong crowd. Soon they are in trouble, and it falls to their parents to get them back on the right track. So, what if their parents got them on the wrong track in the first place? Such, it seems was the case with Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, better known as Bonnie and Clyde. No one really knew about the inner workings of Bonnie and Clyde’s gang of thugs. Still, the evidence was mounting, even if the payoffs to the police kept most of that information from getting to the people who needed it.

As sometimes happens, children grow up and start hanging out with the wrong crowd. Soon they are in trouble, and it falls to their parents to get them back on the right track. So, what if their parents got them on the wrong track in the first place? Such, it seems was the case with Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, better known as Bonnie and Clyde. No one really knew about the inner workings of Bonnie and Clyde’s gang of thugs. Still, the evidence was mounting, even if the payoffs to the police kept most of that information from getting to the people who needed it.

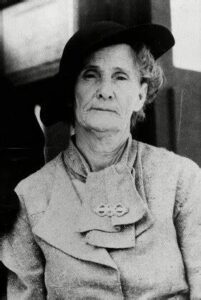

After Bonnie and Clyde, as well as Clyde’s brother Marvin “Buck” Barrow were killed, the US Government began their investigation against most of the Barrow clan, including Clyde Barrow’s mom, Cumie Barrow. In all, more than a dozen family members were put on trial. Strangely, Clyde Barrow’s dad, Henry was not among then. The main focus was on Clyde’s mom, Cumie Barrow. During his closing argument, US attorney for the Northern District of Texas, Clyde O Eastus made a surprising allegation. Pointing at Clyde’s mother, Cumie Barrow, Eastus roared: “She is the ringleader in this conspiracy!” Of course, he was right. I find it odd that she had been given a Hebrew name. If you recall, during one of His miracles, Jesus said to a young girl who had died, “Talitha Cumi” which means “Young girl, arise.” Cumie’s parents turned it around a little and changed the spelling of Cumi to Cumie, but the meaning is still there, just translated “Arise, young girl.” Ironically, Cumie did arise, but it was not to do good, nor was it in any way miraculous, but rather pure evil.

Eastus was probably embellishing his point for the Dallas jury a little bit, by putting Cumie front and center, but he did so because she admitted meeting regularly with the fugitives and was known to provide them with food, clothing and other comforts. Still, when we look back on Bonnie and Clyde’s history, the claims made by Eastus were likely spot on. Cumie was in this a deep as anyone, and especially as deep as Bonnie and Clyde. Reports indicate that Henry and Cumie always lived modestly in their little house, running their service station, and for all intents and purposes not possessing any large amounts of money. It is said that Bonnie and Buck’s wife, Blanche gave some money to their mothers, but the bulk of the money the men stole went to Cumie, to be managed and doled out as needed. It mostly went to the boys and their partners, and to the police, judges, and anyone else that Cumie needed to buy off to save her sons from going to jail. Cumie truly was the woman behind Clyde Barrow.

The police and judges in that era were often under paid and under trained, so it was much easier to bribe them, and Cumie would do whatever it took. Cumie worked very hard to paint herself as the loving mother, who was just looking out for her sone. She was almost certainly more complicit than that. Cumie Walker was born near Swift, Texas, in 1874. She married Henry Barrow just after she turned 17. She was far more literate than her husband, who had been sickly and never went to school. The couple started farming, but they were unsuccessful. As their family grew, Cumie became savvy in survival skills. In 1922 they moved to Dallas and Henry began peddling scrap.

In early 1930, he met and fell head over heels for Bonnie Parker, an animated, petite blond who was separated from her teen husband. Just a few weeks later, though, Clyde was arrested and eventually sent to Waco, Texas, where he was quickly tried and convicted for several thefts and burglaries. Authorities in Houston then blamed him for a murder several months before. With Clyde facing 14 years in prison and a murder charge, Cumie gave an interview to the Waco News-Tribune, insisting he was in Dallas, not Houston at the time of the murder. She attributed his troubles to falling in with a bad group of young men and noted, correctly, that he had previously been charged, but never convicted, of a crime. She also told a whopper: “Clyde was just 18 last Monday.” In reality, he was at least two years older than that. Nevertheless, she knew that the state tended to be more lenient with teens, so she did what she had to do. The reality is that he was likely 21.

The murder charge was dropped when another suspect emerged. But when Clyde arrived at the state penitentiary to serve his sentence, he listed his age as 18. Then Cumie told an even bigger lie. She said that her son was needed at home, because she was widowed, and he was needed to help provide for the family. She and Henry had moved their tiny hand-built house to a West Dallas lot where Henry ran a modest filling station from a front room. Henry Barrow was very much alive.

The corruption in those days was definitely cringeworthy. Either Cumie or her lawyers also collected recommendation letters from the sheriff who held Clyde in the Waco jail, the judge who sentenced him, and other officials who supported his release. He should never have been released, and the people he murdered after being released might have lived full lives, had he not been released. Nevertheless, the state pardon board concurred, recommending his parole because “Barrow was only 18 years old when he got into his trouble,” and he would go home to “support and care for” his mother. Of course, Clyde did support his mother, but not by honest means. Within a year, he was linked to at least four murders, some kidnappings, and all kinds of robberies. Still, his mother was quick to defend him, portraying him as “a kind son who came by the gas station just after Christmas to give her a hug and kiss.” She worried aloud that “We may hear any minute that he’s dead.” She claimed that she asked him if he had killed anyone, and he promptly told her, “Mother, I haven’t never done anything as bad as kill a man.” She insisted, “Everybody likes Clyde, you know,” sharing some family photos of her son. Looking at one of them, she sobbed. “Clyde…isn’t a… murderer.”

By July 1933, her son Buck was dying from injuries suffered in two shootouts, including a bullet to his head. Cumie was devastated. She immediately drove with several family members to Iowa. Again, she stood by Clyde, refusing to urge him to turn himself in. She knew that if he surrendered, he would almost certainly be executed. She said, and if he didn’t surrender, officers would likely shoot to kill. “So, I’m going to let him live his last few days the way he wants to.” Bonnie and Clyde were killed on May 23, 1934.

In an early 1935 trial, after closing arguments, the all-male jury found everyone guilty. Even though prosecutor Eastus had condemned Cumie Barrow, the lenient Judge William Atwell struggled to sentence her. Her influence still held firm. Finally, he said, “Perhaps sixty days in jail will suffice.” Then, he asked Cumie, “What do you think of the sentence? Is it fair?” Her eyes red from crying, Cumie looked at him, her hands clasped together. S

he implored, “Judge, won’t thirty days be long enough? I am needed at home.” And in true corruption style, the judge said, “Thirty days in jail.” Cumie died August 14, 1942, at home, after being sick for three or four weeks. She was 67 years old. Of her seven children, Buck and Clyde were dead, two daughters who lived in Dallas had no police records, and the other three were in prison. What a hideous legacy she left.

he implored, “Judge, won’t thirty days be long enough? I am needed at home.” And in true corruption style, the judge said, “Thirty days in jail.” Cumie died August 14, 1942, at home, after being sick for three or four weeks. She was 67 years old. Of her seven children, Buck and Clyde were dead, two daughters who lived in Dallas had no police records, and the other three were in prison. What a hideous legacy she left.

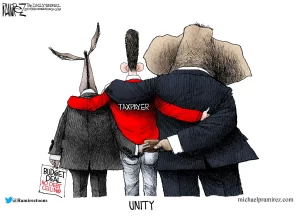

George Washington was not just our first president, but he was also an incredibly intelligent man. Normally, when George Washington spoke, people listened. Maybe his leadership was a big part of what made our system of government work so well, but there was one thing that everyone decided to ignore…his warnings about political parties. George Washington was against them, you see. He wasn’t just against one side of the political party system. He was against having political parties at all. He was so adamantly against them, that he remained nonpartisan throughout his entire presidency.

George Washington was not just our first president, but he was also an incredibly intelligent man. Normally, when George Washington spoke, people listened. Maybe his leadership was a big part of what made our system of government work so well, but there was one thing that everyone decided to ignore…his warnings about political parties. George Washington was against them, you see. He wasn’t just against one side of the political party system. He was against having political parties at all. He was so adamantly against them, that he remained nonpartisan throughout his entire presidency.

In his farewell address, President Washington said the following about partisan politics, “It serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens  the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus, the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.” Any of this sound familiar? Of course, it does. It is exactly what we have going on today.

the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus, the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.” Any of this sound familiar? Of course, it does. It is exactly what we have going on today.

I agree with President Washington, who worried that political parties would become too powerful, rob the people of their control over their own government, and distract everyone from what they should really be focusing on. In today’s political arena, that is exactly what is going on. People are being indited as a way of weaponizing politics. If someone doesn’t agree with the other party, or can’t be controlled, they are very likely to be politically ostracized and attacked. Since George Washington spoke those words, 250 years have passed, and there are people saying that they don’t trust either political party. I am one of those. I suppose some  people would wonder how we would elect our leaders. To them, I say, “How about electing them on their merits!!” There are people out there who will simply vote for the party they are affiliated with, no matter what their candidate stands for. They vote the way they vote, simply because the candidate they choose is from their party. What a horrible mistake that is. Isn’t it time that we find out what our candidates really stand for, and then vote our conscience? Isn’t it time we hold our politicians accountable for their actions? I think it is, but then we would have to find a way to get the correct information, and we already know that we can’t trust the media!! But that is another story.

people would wonder how we would elect our leaders. To them, I say, “How about electing them on their merits!!” There are people out there who will simply vote for the party they are affiliated with, no matter what their candidate stands for. They vote the way they vote, simply because the candidate they choose is from their party. What a horrible mistake that is. Isn’t it time that we find out what our candidates really stand for, and then vote our conscience? Isn’t it time we hold our politicians accountable for their actions? I think it is, but then we would have to find a way to get the correct information, and we already know that we can’t trust the media!! But that is another story.

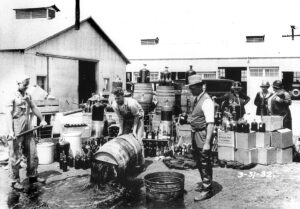

As many of us know, from history, there was a time in United States history when alcohol was illegal. Some will debate if it should still be today, but it is not. Prohibition, as it was called, ran from 1920 to 1933. Prohibition in the United States was a nationwide constitutional ban on the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. The Prohibitionists were led by pietistic Protestants. The idea was to heal what they saw as an ill society beset by alcohol-related problems such as alcoholism, family violence and saloon-based political corruption. There are many alcohol related issues that really do fall into these categories, but you can’t make people stop something that they are intent on doing. Drugs are the same, but we have to draw the line somewhere, or we will have a “zombieistic” society.

As many of us know, from history, there was a time in United States history when alcohol was illegal. Some will debate if it should still be today, but it is not. Prohibition, as it was called, ran from 1920 to 1933. Prohibition in the United States was a nationwide constitutional ban on the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. The Prohibitionists were led by pietistic Protestants. The idea was to heal what they saw as an ill society beset by alcohol-related problems such as alcoholism, family violence and saloon-based political corruption. There are many alcohol related issues that really do fall into these categories, but you can’t make people stop something that they are intent on doing. Drugs are the same, but we have to draw the line somewhere, or we will have a “zombieistic” society.

As Prohibition progressed, many communities introduced alcohol bans and enforcement of these new prohibition laws became a topic of debate. Prohibition supporters were called “Drys.” The “Drys” presented prohibition as a battle for public morals and health. The progressives, along with the Democratic and Republican parties picked up on the movement, and it gained a national grassroots base through the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. After 1900, it was coordinated by the Anti-Saloon League. There were those who opposed Prohibition, including the beer industry, who mobilized “Wet” supporters from the wealthy Catholic and German Lutheran communities, but the influence of these groups receded from 1917 following the entry of the United States into the First World War against Germany.

By a succession of state legislatures, the alcohol industry was curtailed, and finally ended nationwide under the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920. The Eighteenth Amendment passed “with a 68 percent supermajority in the House of Representatives and 76 percent support in the Senate,” as well as ratification by 46 out of the 48 states we had at the time. That enabled legislation, known as the Volstead Act, which set down the rules for enforcing the federal ban and defined the types of alcoholic beverages that were prohibited. Unlike most people think, not all alcohol was banned. For example, religious use of wine was permitted. Private ownership and consumption of alcohol were not made illegal under federal law, but local laws were stricter in many areas, with some states banning possession outright.

With prohibition came the criminal element associated with a refusal to comply. Criminal gangs gained control of the beer and liquor supply in many cities. By the late 1920s, a new opposition to Prohibition emerged nationwide. Critics attacked the policy saying it was actually causing more crime, lowering local revenues, and imposing “rural” Protestant religious values on “urban” America. In another bizarre twist of Prohibition in the United States, the United States government literally decided that if people would not comply with the new law, they would make the penalty much stiffer. When the people continued to consume alcohol despite its being banned, law officials got frustrated and decided to try a different kind of deterrent…death. They literally ordered the poisoning of industrial alcohols manufactured in the United States. These were products regularly stolen by bootleggers to use is making moonshine. By the end of Prohibition in 1933, the federal poisoning program is estimated to have killed at least 10,000 people.

Prohibition ended with the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment, which repealed the Eighteenth  Amendment on December 5, 1933, though prohibition continued in some states. To date, this is the only time in American history in which a constitutional amendment was passed for the purpose of repealing another. Looking back on Prohibition, you will find researchers who say that alcohol consumption declined substantially due to Prohibition. They will also say that rates of liver cirrhosis, alcoholic psychosis, and infant mortality declined as well. Prohibition’s effect on rates of crime and violence is rather another story, because of the criminal element that made and sold alcohol in spite of the law. Nevertheless, Prohibition lost supporters every year it was in action, and lowered government tax revenues at a critical time before and during the Great Depression. I guys it all comes down to money in the end.

Amendment on December 5, 1933, though prohibition continued in some states. To date, this is the only time in American history in which a constitutional amendment was passed for the purpose of repealing another. Looking back on Prohibition, you will find researchers who say that alcohol consumption declined substantially due to Prohibition. They will also say that rates of liver cirrhosis, alcoholic psychosis, and infant mortality declined as well. Prohibition’s effect on rates of crime and violence is rather another story, because of the criminal element that made and sold alcohol in spite of the law. Nevertheless, Prohibition lost supporters every year it was in action, and lowered government tax revenues at a critical time before and during the Great Depression. I guys it all comes down to money in the end.

Fire safety measures have vastly improved over the years, but in the early 1900s, no such safety measures existed. That would prove deadly on March 25, 1911 in New York City. People didn’t really know about materials that were more flammable, other than wood. Nevertheless, wood was the main material used in buildings, and in fact, still is today. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory was owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris. It was located in the top three floors of the Asch Building, on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, in Manhattan. These days that is not really a place we would expect to see a factory…much less a sweatshop, but the Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s factory was a true sweatshop. They employed mostly young immigrant women who worked in a cramped space at lines of sewing machines. Nearly all the workers were teenaged girls who did not speak English and made only about $15 per week working 12 hours a day, every day.

Fire safety measures have vastly improved over the years, but in the early 1900s, no such safety measures existed. That would prove deadly on March 25, 1911 in New York City. People didn’t really know about materials that were more flammable, other than wood. Nevertheless, wood was the main material used in buildings, and in fact, still is today. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory was owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris. It was located in the top three floors of the Asch Building, on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, in Manhattan. These days that is not really a place we would expect to see a factory…much less a sweatshop, but the Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s factory was a true sweatshop. They employed mostly young immigrant women who worked in a cramped space at lines of sewing machines. Nearly all the workers were teenaged girls who did not speak English and made only about $15 per week working 12 hours a day, every day.

In 1911, the Asch Building had four elevators with access to the factory floors, but only one was fully operational and the workers had to file down a long, narrow corridor in order to reach it. There were also two stairways down to the street, but one was locked from the outside to prevent stealing and the door of the other only opened inward. The fire escape was so narrow that it would have taken hours for all the workers to use it, even in the best of circumstances…in an emergency, it was almost useless. Pretty much everyone knew about the danger of fire in factories like the Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory, but high levels of corruption in both the garment industry and city government ensured that no useful precautions were taken to prevent fires. The  problem was that making the factories safe cost money, and dug into the profits, so the owners didn’t want to do what was necessary to save lives. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory’s owners were known to be particularly anti-worker in their policies and had played a critical role in breaking a large strike by workers the previous year.

problem was that making the factories safe cost money, and dug into the profits, so the owners didn’t want to do what was necessary to save lives. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory’s owners were known to be particularly anti-worker in their policies and had played a critical role in breaking a large strike by workers the previous year.

On March 25, a Saturday afternoon, there were 600 workers at the factory when a fire began in a rag bin. The manager attempted to use the fire hose to extinguish it, but was unsuccessful. The hose was rotted and its valve was rusted shut. They were at the mercy of the raging inferno. The fire grew and the workers panicked. They tried to exit the building by the elevator, but it could only hold 12 people and the operator was able to make just four trips before it broke down due to the heat and flames. In a desperate attempt to escape the flames. The girls left behind waiting for the elevator plunged down the shaft to their deaths. The girls who fled by way of the stairwells also met awful fates. When they found a locked door at the bottom of the stairs, many were burned alive. In all, 145 workers between the ages of 14 and 43, mostly women and mostly in their teens and early twenties, died that day. Six of them would not be identified until February, 2011…100 years later.

Once the fire was reported, the firefighters tried to put it out, but their ladders would only reach the seventh floor. The fire was on the eighth floor. When escape was proven to be impossible, the girls, desperate to escape the searing heat and flames, began to jump. The bodies of those who jumped landed on the hoses, hampering the flow. The firemen got out nets to catch the girls, but they jumped three at a time, tearing the nets. The nets were of no real help. Within 18 minutes, it was all over. Of the dead, 49 workers had burned to death or been suffocated by smoke, 36 were dead in the elevator shaft and 58 died from jumping to the sidewalks. Two  more died later from their injuries. The workers’ union set up a march on April 5 on New York’s Fifth Avenue to protest the conditions that had led to the fire. It was attended by 80,000 outraged people. Despite a good deal of evidence that the owners and management had been horribly negligent in the fire, a grand jury failed to indict them on manslaughter charges. The tragedy did result in some good, however. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union was formed in the aftermath of the fire and the Sullivan-Hoey Fire Prevention Law was passed in New York that October. Both were crucial in preventing similar disasters in the future. Still, I think that it will take the memory of the victims of corruption to ever really inspire people to change the way things are.

more died later from their injuries. The workers’ union set up a march on April 5 on New York’s Fifth Avenue to protest the conditions that had led to the fire. It was attended by 80,000 outraged people. Despite a good deal of evidence that the owners and management had been horribly negligent in the fire, a grand jury failed to indict them on manslaughter charges. The tragedy did result in some good, however. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union was formed in the aftermath of the fire and the Sullivan-Hoey Fire Prevention Law was passed in New York that October. Both were crucial in preventing similar disasters in the future. Still, I think that it will take the memory of the victims of corruption to ever really inspire people to change the way things are.