coal mines

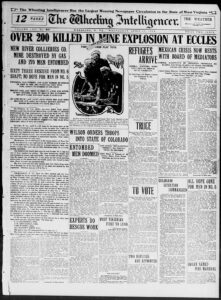

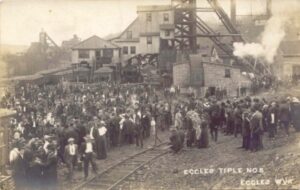

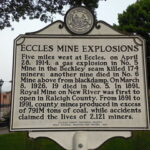

If you lived in Eccles, West Virginia in 1914, you or someone in your family most likely worked at the Eccles Mine Number 5. Eccles was a tiny town in Raleigh County. Mine number 5 was opened in 1905, and by 1914, the mine employed most of the local men and even the teenagers. Life was mundane for the most part. Not much happened in the town, and April 28, 1914 promised to be just another boring day. On that Tuesday morning, dozens of local men and teens left their homes to go to work at the Eccles Mine Number 5, which was one of group of coal mines in West Virginia owned by the New River Colliers Company. Everything was going along fine, when suddenly, at 2:30pm, a sudden explosion rocked the Number 5 mine. In an instant, more than 180 workers who had left home as usual that day, would never go home again.

If you lived in Eccles, West Virginia in 1914, you or someone in your family most likely worked at the Eccles Mine Number 5. Eccles was a tiny town in Raleigh County. Mine number 5 was opened in 1905, and by 1914, the mine employed most of the local men and even the teenagers. Life was mundane for the most part. Not much happened in the town, and April 28, 1914 promised to be just another boring day. On that Tuesday morning, dozens of local men and teens left their homes to go to work at the Eccles Mine Number 5, which was one of group of coal mines in West Virginia owned by the New River Colliers Company. Everything was going along fine, when suddenly, at 2:30pm, a sudden explosion rocked the Number 5 mine. In an instant, more than 180 workers who had left home as usual that day, would never go home again.

The explosion was caused by coal-seam methane. At least 180 men lay dead, at least that was the death roll published as of 2011 by the National Coal Heritage Trail. A monument at the cemetery lists 183 victims, and  the records of the county coroner list 186. When the mine was rocked by a series of violent explosions, parts of the mine collapsed while other parts were heavily damaged, which trapped the miners inside. Of course, the people of Eccles and officials from the mining company rushed to the scene to aid the rescue efforts. Despite their best efforts, it was soon obvious that this would be a recovery effort, and not a rescue. That day, all of the miners in Eccles Mine Number 5 were killed, including five who were under the age of 14 years of age. In addition, nine workers in a nearby mine were killed when deadly gas from Mine Number 5 seeped into their mine. Ironically, one of the men who died in the nearby mine, was an insurance agent from Charleston, West Virginia, who had only gone into the mine to solicit business from the men. He was only there for a few minutes. It was there that the salesman, who had unfortunately chosen that day to visit the mine and sell insurance to its workers, was also killed. The blast and the subsequent damage to the mine, left many of the victim so mangled and torn apart, that most of them could not be positively identified because of their horrific injuries.

the records of the county coroner list 186. When the mine was rocked by a series of violent explosions, parts of the mine collapsed while other parts were heavily damaged, which trapped the miners inside. Of course, the people of Eccles and officials from the mining company rushed to the scene to aid the rescue efforts. Despite their best efforts, it was soon obvious that this would be a recovery effort, and not a rescue. That day, all of the miners in Eccles Mine Number 5 were killed, including five who were under the age of 14 years of age. In addition, nine workers in a nearby mine were killed when deadly gas from Mine Number 5 seeped into their mine. Ironically, one of the men who died in the nearby mine, was an insurance agent from Charleston, West Virginia, who had only gone into the mine to solicit business from the men. He was only there for a few minutes. It was there that the salesman, who had unfortunately chosen that day to visit the mine and sell insurance to its workers, was also killed. The blast and the subsequent damage to the mine, left many of the victim so mangled and torn apart, that most of them could not be positively identified because of their horrific injuries.

In the early 1900s, coal was in great demand. Production in the United States had increased from 50 million tons of coal in 1850 to 250 million tons of coal in 1903. Unfortunately, the increasing demand and the rush to supply, brought with it worsening work conditions. The danger occurred when the men were digging for coal in deep mines, in which chambers of gas lay just underneath. That meant that highly explosive gasses could come into contact with carbide headlamps. The next thing they knew, they had an explosion on their hands. The mine

disaster brought attention to an overall safety problem in the West Virginia mining industry. Sadly…at least in that it didn’t happen sooner, the disaster actually aided the unions’ attempts to improve the workers’ conditions. The labor union helped to ban carbide headlamps in West Virginia. It was suspected that the headlamps were most likely the cause of the Eccles explosion, as well as a second mine explosion 18 years later in Illinois.

disaster brought attention to an overall safety problem in the West Virginia mining industry. Sadly…at least in that it didn’t happen sooner, the disaster actually aided the unions’ attempts to improve the workers’ conditions. The labor union helped to ban carbide headlamps in West Virginia. It was suspected that the headlamps were most likely the cause of the Eccles explosion, as well as a second mine explosion 18 years later in Illinois.

Uncle Eddie Hein was a soft-spoken man, but that didn’t mean that he wasn’t a funny man. He loved to laugh, and he had a great laugh too. That is probably one of the things I miss most about Uncle Eddie…that and the great smile that went with the great laugh. He loved practical jokes…like pretending to give my husband, Bob Schulenberg, his nephew, a buzzcut in the 70s, when long hair was the style. I think Bob knew that the clippers weren’t plugged in, but he went along with the joke anyway. It is my guess that my in-laws, Walt and Joann Schulenberg put Eddie up to the joke, almost hoping he would actually cut Bob’s hair. Of course, Eddie would never have done that, but it was a funny thought anyway. It was a typical kind of joke Eddie would pull on people.

Uncle Eddie Hein was a soft-spoken man, but that didn’t mean that he wasn’t a funny man. He loved to laugh, and he had a great laugh too. That is probably one of the things I miss most about Uncle Eddie…that and the great smile that went with the great laugh. He loved practical jokes…like pretending to give my husband, Bob Schulenberg, his nephew, a buzzcut in the 70s, when long hair was the style. I think Bob knew that the clippers weren’t plugged in, but he went along with the joke anyway. It is my guess that my in-laws, Walt and Joann Schulenberg put Eddie up to the joke, almost hoping he would actually cut Bob’s hair. Of course, Eddie would never have done that, but it was a funny thought anyway. It was a typical kind of joke Eddie would pull on people.

Eddie is my father-in-law, Walt Schulenberg’s half brother, and so it was an annual trip from Casper, Wyoming to Forsyth, Montana that the Schulenberg’s took each year, to keep the family close to the aunt, uncles, and cousins that lived there, as well as to my father-in-law’s mom, Vina Hein, and step-dad, Walt Hein. When Bob and I got married, we wanted to continue that tradition, and I have always been glad we did. My girls had the privilege of knowing some of the most amazing people through those trips. I have always believed in the importance of family, and have hopefully instilled those same traditions on my kids and grandkids.

Eddie was a hard-working man, who worked hard in the coal mines, and then came home to work hard around the home he shared with his wife, Pearl, and children, Larry and Kim. He turned their smaller mobile home into a very nice house, with plenty of room for the whole family. He and Pearl also raised a wonderful garden, and canned lots and lots of vegetables. That garden saved the family lots of money in grocery bills. Canning I could do, but gardening…not so much, so I don’t mind telling you that I was a little bit jealous of those who can grow gardens, vegetable or flower.

Eddie was a mechanic by trade, and never really wanted to be a rancher, although he could do that work too. I think Eddie could do anything he put his mind to. He was a very talented Jack of all Trades. The Forsyth area is abundant in river rock, because of the Yellowstone River that flows through town. Eddie built a beautiful

fireplace in their home out of that river rock. It was just stunning, and one of my favorite parts of the home he built. It not only heated the home, but it made it look amazing too. Eddie also helped my father-in-law when he was building the house he built in the Casper area.

fireplace in their home out of that river rock. It was just stunning, and one of my favorite parts of the home he built. It not only heated the home, but it made it look amazing too. Eddie also helped my father-in-law when he was building the house he built in the Casper area.

Eddie went home to be with the Lord on October 16, 2019, and we all miss him very much. In my mind’s eye, I can still visualize his smiling face and his great laugh. Today would have been Uncle Eddies 78th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Eddie. We love and miss you very much.

My nephew, Matt Miller actually joined our family…officially, on August 14, 2021, when he married my niece, Michelle Stevens. While that was the official date, Matt has really been part of our family much longer. Matt and Michelle actually met in middle school. At that point, they became friends, but neither of them knew the future God had planned for this friendship. God planned for their friendship to grow into something so much deeper. As time went on, they knew that theirs was to be love and friendship, not just friendship. Their wedding this summer was the culmination of their years of loveship.

My nephew, Matt Miller actually joined our family…officially, on August 14, 2021, when he married my niece, Michelle Stevens. While that was the official date, Matt has really been part of our family much longer. Matt and Michelle actually met in middle school. At that point, they became friends, but neither of them knew the future God had planned for this friendship. God planned for their friendship to grow into something so much deeper. As time went on, they knew that theirs was to be love and friendship, not just friendship. Their wedding this summer was the culmination of their years of loveship.

These days, Matt and Michelle are working hard and saving their money, because it is their dream to buy a house on a piece of land. Matt wants a large shop where he can work on things and just tinker around. He loves working on things like vehicles, and if they have land, I’m sure a riding lawnmower will follow. Michelle is so proud of her husband, because he visualizes a plan, and works hard to bring it to pass. The long shifts at the coal mines are not easy, and have sometimes meant that he and Michelle don’t see each other for two or three days, because of their shift differences. I get that too, because my own husband worked in the uranium mines. It tough of them and it makes it kind of lonely for them too. Nevertheless, Matt wants the very best for his wife and future kids, and their dream is land, so that is what he is going to do. Matt has recently really gotten into snowmobiling this year too, so I’m sure his shop will include tinkering on the snowmobiles that they will most likely own soon.

Of course, no man can work all the time, and hunting allows Matt to have fun and provide meat for the family table. Matt and his dad, love to go hunting, fishing, and they share a love of guns. Matt and his dad went bow hunting for elk this year, and both got their elk. That is so uncommon. Usually one or both will have to go hunt

with a rifle in order to get their elk too. Game animals are elusive, you know. It was really fun for them to succeed in getting their elk with a bow. I have no idea how to shoot an arrow with a bow…much less have enough skill to actually bag an elk with a bow. That is really something to be super proud of. It’s really been a great year for Matt. Now, he and Michelle are really looking forward to all the good things God has in store for them in the future. Today is Matt’s birthday. Happy birthday Matt!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

with a rifle in order to get their elk too. Game animals are elusive, you know. It was really fun for them to succeed in getting their elk with a bow. I have no idea how to shoot an arrow with a bow…much less have enough skill to actually bag an elk with a bow. That is really something to be super proud of. It’s really been a great year for Matt. Now, he and Michelle are really looking forward to all the good things God has in store for them in the future. Today is Matt’s birthday. Happy birthday Matt!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

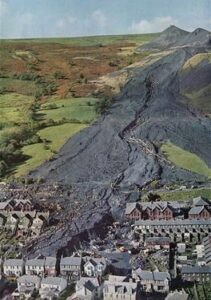

On the morning of October 21, 1966, a catastrophic collapse of a colliery spoil tip occurred on a mountain slope above the Welsh village of Aberfan, near Merthyr Tydfil. A spoil tip, also called a boney pile, culm bank, gob pile, waste tip, or…in Scotland, bing, is a pile built of accumulated spoil…waste material removed during mining. These waste materials are typically composed of shale, but they also contain smaller quantities of carboniferous sandstone and other residues. Spoil tips are not formed of slag, but in some areas, such as England and Wales, they are referred to as slag heaps. The area near Aberfan overlaid a natural spring, and a period of heavy rain led to a build-up of water within the tip which caused it to suddenly slide downhill as a slurry. The disaster killed 116 children and 28 adults, as it engulfed Pantglas Junior School and a row of houses. The accident left just five survivors and wiped out half the town’s youth. The Aberfan disaster became one of the United Kingdom’s worst coal mining accidents, but strangely it isn’t anything like a normal coal mining accident.

On the morning of October 21, 1966, a catastrophic collapse of a colliery spoil tip occurred on a mountain slope above the Welsh village of Aberfan, near Merthyr Tydfil. A spoil tip, also called a boney pile, culm bank, gob pile, waste tip, or…in Scotland, bing, is a pile built of accumulated spoil…waste material removed during mining. These waste materials are typically composed of shale, but they also contain smaller quantities of carboniferous sandstone and other residues. Spoil tips are not formed of slag, but in some areas, such as England and Wales, they are referred to as slag heaps. The area near Aberfan overlaid a natural spring, and a period of heavy rain led to a build-up of water within the tip which caused it to suddenly slide downhill as a slurry. The disaster killed 116 children and 28 adults, as it engulfed Pantglas Junior School and a row of houses. The accident left just five survivors and wiped out half the town’s youth. The Aberfan disaster became one of the United Kingdom’s worst coal mining accidents, but strangely it isn’t anything like a normal coal mining accident.

The colliery spoil tip was the responsibility of the National Coal Board (NCB), and the inquiry into the disaster placed the blame on the organization, also naming nine employees. When everything broke loose, the resulting landslide sent 140,000 cubic yards of coal waste in a tidal wave 40-feet high hurtling  down the mountainside where Merthyr Vale Colliery stood. The slide destroyed farmhouses, cottages, houses, and part of the neighboring County Secondary School. The avalanche is thought to have been the result of shoddy construction and a build-up of water in one of the colliery’s spoil tips…piles of waste material removed during mining.

down the mountainside where Merthyr Vale Colliery stood. The slide destroyed farmhouses, cottages, houses, and part of the neighboring County Secondary School. The avalanche is thought to have been the result of shoddy construction and a build-up of water in one of the colliery’s spoil tips…piles of waste material removed during mining.

Like many countries and areas, Wales was known for coal mining during the Industrial Revolution. Aberfan’s colliery opened in 1869. It didn’t take long for it to run out of space for waste, and by 1916 the space on the mountain valley floor was full. At that point, the colliery started “tipping” on the mountainside above the town. In 1966 it amassed seven tips containing 2.7 million cubic yards of colliery spoil.

Aberfan’s town council had contacted the National Coal Board to express concerns over the spoil tips years  before the incident, following a non-lethal accident on the colliery. Unfortunately, they took no action at that time, and the issue was never addressed. The tip that fell on October 21 covered material that previously slipped. The disaster received widespread national attention. Queen Elizabeth II did not visit the site until eight days after the accident, and she admitted later that not going sooner was one of her biggest regrets. Once the disaster happened, little can be done to fix the matter, but the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act was passed in 1969 to add provisions when using mining tips, among other things. Sadly it was too late for those lost, but it was good news for future miners and the surrounding towns.

before the incident, following a non-lethal accident on the colliery. Unfortunately, they took no action at that time, and the issue was never addressed. The tip that fell on October 21 covered material that previously slipped. The disaster received widespread national attention. Queen Elizabeth II did not visit the site until eight days after the accident, and she admitted later that not going sooner was one of her biggest regrets. Once the disaster happened, little can be done to fix the matter, but the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act was passed in 1969 to add provisions when using mining tips, among other things. Sadly it was too late for those lost, but it was good news for future miners and the surrounding towns.

Underground mining, as we all know is dangerous. It was even more dangerous in the 1800s, when the equipment used was much more primitive. Still, many mining companies have switched to open pit mining to avoid the possibility of a cave in. One of the most dangerous forms of underground mining was and still is coal mining. The distinct possibility of a build up of methane gas makes underground coal mining a deadly venture for many miners. Aside from breathing the deadly gas and coal dust, causing death, either instantaneously or later in life…from black lung, the danger of an explosion was always present.

Underground mining, as we all know is dangerous. It was even more dangerous in the 1800s, when the equipment used was much more primitive. Still, many mining companies have switched to open pit mining to avoid the possibility of a cave in. One of the most dangerous forms of underground mining was and still is coal mining. The distinct possibility of a build up of methane gas makes underground coal mining a deadly venture for many miners. Aside from breathing the deadly gas and coal dust, causing death, either instantaneously or later in life…from black lung, the danger of an explosion was always present.

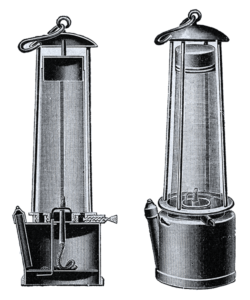

One of the most dangerous parts of underground mining, was the miner’s inability to see, or rather the lanterns used to solve the problem of the miner’s inability to see. It’s pretty difficult to maneuver around in a mine, much less find ore, if you can’t see, and caves don’t generally have built in lights. Miners these days have battery powered lights on their hard hats, but those things didn’t exist in the 1800s. Most generally the miners carried a lantern, filled with heavy vegetable oil and using a wick that was unprotected, thus allowing it to ignite the methane or other flammable gasses, called firedamp or minedamp, lurking undetected in the mine.

The problem needed to be solved, and so several inventors began looking into just how to do that. Probably the best one, at that time, was the Davy lamp. It is a safety lamp designed specifically for use in flammable atmospheres. It was invented in 1815 by Sir Humphry Davy. They didn’t have light bulbs or batteries that could be used in the mines back then. The Davy Lamp consists of a wick lamp with the flame enclosed inside a mesh screen. The mesh screen kept the flame from escaping, thereby reducing the danger of explosions. The Davy Lamp also provided a test for the presence of gases. If flammable gas mixtures were present, the flame of the Davy lamp burned higher with a blue tinge. The lamps were equipped with a metal gauge to measure the height of the flame. When the lamp was placed close to the ground, it could detect gases, such as carbon dioxide, that are more dense than air and so could collect in depressions in the mine. If the lamp determined that the mine air was oxygen-poor (asphyxiant gas), the lamp flame would be extinguished, using a black damp or chokedamp. A methane-air flame is extinguished at about 17% oxygen content…which will still support life, so the lamp gave an early indication of a dangerous atmosphere, allowing the miners to get out before they died of asphyxiation.

Apparently, Davy’s invention was preceded by that of William Reid Clanny, an Irish doctor at Bishopwearmouth, who had read a paper to the Royal Society in May 1813. The Clanny lamp was more cumbersome, but it was successfully tested at Herrington Mill, and he won medals, from the Royal Society of Arts. Another lamp version was the lamp designed by engine-wright George Stephenson. His “Geordie Lamp” drew air in via tiny holes, through which the flames of the lamp could not pass. If you ask me, the metal plate, only allowing small pin points of light would not be a very illuminating. A month before Davy presented his design to the Royal Society,  Stephenson supposedly demonstrated his own lamp to two witnesses by taking it down Killingworth Colliery and holding it in front of a fissure from which firedamp was issuing. Unfortunately for Stephenson, Davy beat him to the necessary people.

Stephenson supposedly demonstrated his own lamp to two witnesses by taking it down Killingworth Colliery and holding it in front of a fissure from which firedamp was issuing. Unfortunately for Stephenson, Davy beat him to the necessary people.

The first trial of a Davy lamp with a wire sieve was at Hebburn Colliery on January 9, 1816. Because of its success, Davy was awarded the society’s Rumford Medal. Davy’s lamp differed from Stephenson’s in that the flame was surrounded by a screen of gauze, whereas Stephenson’s prototype lamp had a perforated plate contained in a glass cylinder, which was a design mentioned in Davy’s Royal Society paper, as an alternative to his preferred solution. For his invention Davy was given £2,000 worth of silver. Stephenson, on the other hand, was accused of stealing the idea from Davy. His “Geordie Lamp” had not been demonstrated by Stephenson until after Davy had presented his paper at the Royal Society. While Stephenson was exonerated, Davy went to his grave insisting that he had tried to steal his idea.

Most of us have heard, either from our dads, grandfathers. or great grandfathers about how they or their ancestors had to quit school at an early age to work and help support the family. Life at the turn of the 20th Century was not easy. With the great depression, and poverty everywhere, and no real child labor laws, and the Industrial Revolution in full swing, the kids had little choice but to go out and help their families put food on the table. At that time in history, there were no real child labor laws in place, and there was a need that had to be filled. Whole families were in danger of starvation. The family had to get some money soon. Exceptions were made.

Most of us have heard, either from our dads, grandfathers. or great grandfathers about how they or their ancestors had to quit school at an early age to work and help support the family. Life at the turn of the 20th Century was not easy. With the great depression, and poverty everywhere, and no real child labor laws, and the Industrial Revolution in full swing, the kids had little choice but to go out and help their families put food on the table. At that time in history, there were no real child labor laws in place, and there was a need that had to be filled. Whole families were in danger of starvation. The family had to get some money soon. Exceptions were made.

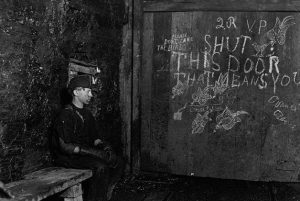

Because of the circumstances of the times, and the need to eat, the nation’s children went to work. They worked in coal mines, factories, agriculture, and every other menial job they could get. So many of these jobs would have detrimental affects on the health of the workers. It was not unusual to find whole families or father-son pairs who were hired together. Unfortunately, children were not given jobs that suited their status as young, impressionable people who aren’t able to really care for themselves, much less do a skilled job. The child laborers were often given the jobs adults physically couldn’t accomplish. That sounds strange to us, but it meant crawling into tiny places the adults could not fit through. As an example, in factories, children were sent into the tiny, cramped interiors of the machines. Their task was to fix mechanisms that the adults simply couldn’t reach. This was dangerous work, and even with doing things the adults couldn’t, children received lower pay than the adults who depended on them.

The small stature of the children ensured that they often had the most dangerous jobs available in the coal mines too. As greasers, the children were constantly in danger of being crushed by carts loaded down with coal, as they ran up and down the tram tracks, a heavy bucket of grease on each arm, making sure the tram axels were appropriately greased at all times. Nippers (also called trappers) were children who had the dangerous responsibility of opening and closing the shaft doors as coal cars came hurtling down the sloped tracks. Boys who fell asleep in the total stillness and darkness…sometimes a mile beneath the surface…would be crushed if they failed to lift the door.

Eventually, activists began to take issue with the treatment of children in positions like these. One photographer…Lewis Hine made it his personal mission to document the situation of children in the coal fields of

Appalachia. Because of his persistence, we have a cache of images documenting this era of American child labor. These and many other images led the US government to pass the Keating-Owens Child Labor Act of 1916. The act created a minimum age of 16 for mine workers, as well as instating the eight-hour workday. Then, shockingly, this act was deemed unconstitutional. The child labor issues continued until the 1930s, when the New Deal brought permanent reform for child laborers.

Appalachia. Because of his persistence, we have a cache of images documenting this era of American child labor. These and many other images led the US government to pass the Keating-Owens Child Labor Act of 1916. The act created a minimum age of 16 for mine workers, as well as instating the eight-hour workday. Then, shockingly, this act was deemed unconstitutional. The child labor issues continued until the 1930s, when the New Deal brought permanent reform for child laborers.

About a month ago, my husband Bob and I went to visit family in Forsyth, Montana. We had a wonderful time visiting, reminiscing, and learning new family information. It was a trip we needed to take, because it had been far too long since our last visit. The family there is just so important to us. We knew we couldn’t let any more time pass before we went to visit. Two of the people we wanted to spend time with, were Bob’s aunt and uncle, Eddie and Pearl Hein. Eddie recently had a couple of strokes, and we wanted to show him how important he is to us, and Pearl had been taking care of him, almost on her own, and since I have been a caregiver, I know that she needs support too, even if it is just moral support. Caregiving is exhausting work, and while the patient wishes they didn’t need you to work so hard…the fact remains that they do, and they know that without you, they would be in a nursing home, or worse. Still, caregiving

About a month ago, my husband Bob and I went to visit family in Forsyth, Montana. We had a wonderful time visiting, reminiscing, and learning new family information. It was a trip we needed to take, because it had been far too long since our last visit. The family there is just so important to us. We knew we couldn’t let any more time pass before we went to visit. Two of the people we wanted to spend time with, were Bob’s aunt and uncle, Eddie and Pearl Hein. Eddie recently had a couple of strokes, and we wanted to show him how important he is to us, and Pearl had been taking care of him, almost on her own, and since I have been a caregiver, I know that she needs support too, even if it is just moral support. Caregiving is exhausting work, and while the patient wishes they didn’t need you to work so hard…the fact remains that they do, and they know that without you, they would be in a nursing home, or worse. Still, caregiving  takes it’s toll on the caregiver, and I was worried about Pearl too. But Pearl loves Eddie, and she did what she had to do, and she has been rewarded with a husband who is healthy again, and getting stronger every day.

takes it’s toll on the caregiver, and I was worried about Pearl too. But Pearl loves Eddie, and she did what she had to do, and she has been rewarded with a husband who is healthy again, and getting stronger every day.

When we saw Eddie and Pearl, we were very pleased to see that they were both doing quite well. They looked a little tired, but then right now, everything they do is harder…physically harder. Eddie is in the process of re-learning how to do many things that we all take for granted every day. I didn’t know what to expect when we were getting ready to see Eddie, even though, Bob’s Uncle Butch Schulenberg had told us that Eddie was really improving. We didn’t know if Eddie could talk well, or walk well, or what. We were so relieved when Eddie walked into Butch’s house, smiling and talking clearly. We were so relieved, but we should not have been  surprised. No, we should have known that Eddie would be back, because he is a strong man, and he won’t ever give up.

surprised. No, we should have known that Eddie would be back, because he is a strong man, and he won’t ever give up.

Eddie spent most of his adult life working in the Peabody coal mine in Colstrip, Montana. He worked hard to support his family, and when he was home, he worked to renovate their home. He and Pearl have always had a garden, and worked together to grow fresh vegetables for their family. In fact, they have both worked hard all their lives. That is what has made them the strong people they are, and that is why I know that Eddie will come back from this stronger than ever. Today is Eddie’s birthday. Happy birthday Eddie!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

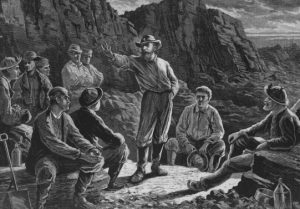

During the Great Potato Famine of September 1845 in Ireland, the leaves on potato plants suddenly turned black and curled, then rotted, seemingly the result of a fog that had rolled across the fields of Ireland. In reality, the cause was an airborne fungus named Phytophthora Infestans. It was originally transported in the holds of ships traveling from North America to England. The resulting loss of the potato crops, put the people of Ireland in dire straits. Many people decided that it was time to immigrate to America. In fact, more than a million people immigrated to America and most settled in the coal regions of Pennsylvania. Many of the Irish Catholics immigrants were routinely met with discrimination based on both their religion and heritage. They often encountered help wanted signs with disclaimers that read, “Irish need not apply.” These days, that practice would have met with harsh retaliation due to anti-discrimination laws.

During the Great Potato Famine of September 1845 in Ireland, the leaves on potato plants suddenly turned black and curled, then rotted, seemingly the result of a fog that had rolled across the fields of Ireland. In reality, the cause was an airborne fungus named Phytophthora Infestans. It was originally transported in the holds of ships traveling from North America to England. The resulting loss of the potato crops, put the people of Ireland in dire straits. Many people decided that it was time to immigrate to America. In fact, more than a million people immigrated to America and most settled in the coal regions of Pennsylvania. Many of the Irish Catholics immigrants were routinely met with discrimination based on both their religion and heritage. They often encountered help wanted signs with disclaimers that read, “Irish need not apply.” These days, that practice would have met with harsh retaliation due to anti-discrimination laws.

I know that a number of my ancestors came from Ireland, and I would not be surprised to find that a number of my ancestors were among those immigrants that came to America to find a better life. The unfortunate thing was that the few people who would hire them, and the few places that would rent to them, were corrupt people. The immigrants finally accepted the most physically demanding and dangerous mining jobs, just to have work. The men and their families were forced to live in overcrowded housing, buy from shops, and visit doctors all “owned” by the company. In many cases, workers wound up owing their employers at the end of  each month. The Irish immigrants were in a very tough situation, but they had been there before, and they were not going to continue to be victimized.

each month. The Irish immigrants were in a very tough situation, but they had been there before, and they were not going to continue to be victimized.

The abuse triggered a period of violence in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, between 1861 and 1875. The violence which included assaults, arsons, and murders were blamed on a secret society of Irish immigrants known as the Molly Maguires. The group originally emerged in northern Ireland in the 1840s, as a branch of the long line of rural secret societies including the Whiteboys and Ribbonmen, who responded to miserable working conditions and evictions by tenant landlords with bloody vengeance. When the Civil War broke out, the Irish immigrants were drafted to serve, and they rebelled by sending out “coffin notices” threatening death, because they perceived the war to be a “rich man’s war,” and they wanted no part of it. The notes were alleged to have been written by the Molly Maguires, because they didn’t want to lose their jobs to scabs. Threats were actually carried out 24 times when foremen and supervisors were assassinated.

In 1873, the president of the Reading Railroad, Franklin Gowen hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to infiltrate and destroy the Molly Maguires, because their union activities were impeding that railroad’s ability to increase profits. The detective, James McParlan, used the alias, James McKenna to infiltrate the group. Oddly, he was an Irishman himself, but I guess money was more important to him. Franklin Gowen served as the chief  prosecutor, even though his railroad holdings made his participation a conflict of interest. Based almost entirely on McParlan’s testimony, 20 men were sentenced to death—10 of whom were executed on June 21, 1877, also known as Black Thursday. The men declared their innocence right up to the end. Although the existence of the Molly Maguires as an organized band of outlaws in America is under debate to this day, most historians now agree that the trials and executions were an outrageous perversion of the criminal justice system. In 1979, more than 100 years following his hanging, John Kehoe, who was the supposed “king” of the Molly Maguires, was granted a full pardon by the state of Pennsylvania.

prosecutor, even though his railroad holdings made his participation a conflict of interest. Based almost entirely on McParlan’s testimony, 20 men were sentenced to death—10 of whom were executed on June 21, 1877, also known as Black Thursday. The men declared their innocence right up to the end. Although the existence of the Molly Maguires as an organized band of outlaws in America is under debate to this day, most historians now agree that the trials and executions were an outrageous perversion of the criminal justice system. In 1979, more than 100 years following his hanging, John Kehoe, who was the supposed “king” of the Molly Maguires, was granted a full pardon by the state of Pennsylvania.