civilians

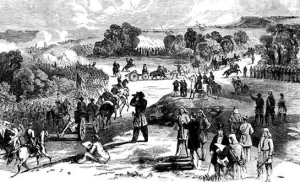

When the gunfire in a battle begins, most of us want to be as far away as possible, including the soldiers fighting in the battle, but in the case of The Battle of Bull Run during the American civil war, this was not the case. In a seriously strange phenomenon, many of Washington’s civilians and the wealthy elite, including congressmen and their families, went on picnics on the sidelines to watch the battle. After that, it became known as “The Picnic Battle” but it was definitely no picnic, as they would soon find out. What no one realized was that The Battle of Bull Run, fought on July 21, 1861, was actually going to be remembered as the first gory conflict in a long and bloody war.

When the gunfire in a battle begins, most of us want to be as far away as possible, including the soldiers fighting in the battle, but in the case of The Battle of Bull Run during the American civil war, this was not the case. In a seriously strange phenomenon, many of Washington’s civilians and the wealthy elite, including congressmen and their families, went on picnics on the sidelines to watch the battle. After that, it became known as “The Picnic Battle” but it was definitely no picnic, as they would soon find out. What no one realized was that The Battle of Bull Run, fought on July 21, 1861, was actually going to be remembered as the first gory conflict in a long and bloody war.

Bull Run was the first land battle of the Civil War. It was a battle that was fought at a time when many Americans believed the war would be short and relatively bloodless. They just really didn’t understand how this was going to play out. So, believe it or not, the civilians went out to watch the war, bringing a picnic lunch along with them. If you think about it, bringing the family and a picnic lunch out to watch a battle, had to seem strange, or even insane, and really it was, but many of the civilians were there because they had to be.

While the reporters were there too, for their own selfish reasons, they were quick to condemn the other civilians who were there, calling them frivolous. The Boston Herald published a lengthy, “not-so-funny” comedy poem about the scene. They were making the civilians look reckless. In the poem, HR Tracy describes a story “lacking in glory” about “careless picnickers who heedlessly went out to watch the battle and then ran away, driving over dead and wounded in their carriages.” This kind of public criticism gave rise to the idea of Bull Run as the “picnic battle” but there was more going on. No one really knows exactly how many civilians were there on that day. The recruits in the battle signed up to Lincoln’s army for a 90-day term, because they all thought the war would be over that fast. It’s also hard to be sure how many watchers there were. Many people say men, women and children, but others say it was mostly men.

The people did bring food and even picnic baskets to watch the battle, but it wasn’t exactly like they thought it was a leisurely day out for either spectators or combatants. Picnic food “was more of a necessity than a frivolous pursuit on a Sunday afternoon,” writes Jim Burgess writes for the Civil War Trust. Just getting to Centreville, where the battle was fought, was a seven-hour carriage ride away from Washington, so they had to take food for the journey, because the local Virginians were not going to offer the Union onlookers any kind of hospitality. Some called them a “throng of sightseers” while others mentioned that they were selling pies and other edibles. I think the whole thing was a misunderstanding of epic proportions. Unfortunately, after the  people found out how horrific the whole thing was, and began to witness the terrible bloodshed, they were also subjected to the snide remarks of the media, as if they didn’t already feel bad enough.

people found out how horrific the whole thing was, and began to witness the terrible bloodshed, they were also subjected to the snide remarks of the media, as if they didn’t already feel bad enough.

The reality was that the battle wasn’t just a spectator sport. It was important politically, so the politicians attended. It was important socially, so the journalists attended. It was also an opportunity to sell food, so the food vendors attended. In the end, it was really a circus, and once it was over, there was no one left who innocently thought that this war would end in 90 days, and no one left that thought there would be little bloodshed.

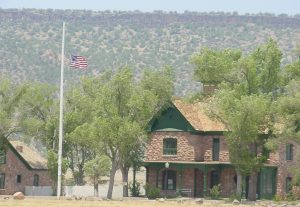

During our nation’s early years, there were many times when we found it necessary to build forts to protect the people in the area. The forts housed the armies and also took in civilians when needed. In 1870, the government built a military post four miles south of what is today, Whiteriver, Arizona. The fort was named Camp Ord, and was named after General O.C. Ord, Commander of Arizona when it was built in the spring. Just a few months later in August, the name was changed to Camp Mogollon, then Camp Thomas in September. It seems almost comical that the name would change so many times, but that was how things were done then, I guess.

During our nation’s early years, there were many times when we found it necessary to build forts to protect the people in the area. The forts housed the armies and also took in civilians when needed. In 1870, the government built a military post four miles south of what is today, Whiteriver, Arizona. The fort was named Camp Ord, and was named after General O.C. Ord, Commander of Arizona when it was built in the spring. Just a few months later in August, the name was changed to Camp Mogollon, then Camp Thomas in September. It seems almost comical that the name would change so many times, but that was how things were done then, I guess.

The post received it’s final name…Camp Apache on February 2, 1871, as a token of friendship to the Apache Indians. Ironically, the soldiers at the fort would soon spend many years at war with these same Indians they were trying to befriend. The fort’s initial purpose was to guard the nearby White Mountain Reservation and Indian agency. The fort was located at the end of a military road on the White Mountain Reservation. Right next to that was the San Carlos Agency. Both reservations would become the focus of Apache unrest, especially after troops moved the troublesome Chiricahuas from Fort Bowie to the White Mountain Reservation in 1876.

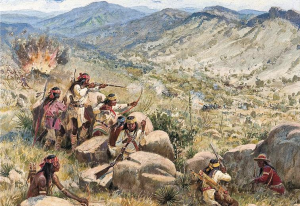

The area was in constant turmoil, mostly because the reservations were noted for their unhealthful location, overcrowded conditions, and dissatisfied inhabitants. Inefficient and corrupt agents added to the problem, and friction between civil and military authorities grew. Several attempts to turn the nomadic Indians into farmers, and an influx on the reservations of settlers and miners only added to the problem, and battles became the normal everyday event. As a result, many of the Indians left the reservations to resume their hunting, gathering, and raiding lifestyle, creating a public outcry from the settlers.

In 1871, General George Crook was named commander of the Department of Arizona. Crook had earned a reputation as an Indian fighter in the Snake War in Idaho and Oregon. Crook quickly realized that his soldiers were no match for the fierce Apache he was sent to subdue, so he made his first trip to Fort Apache. At the reservation, he recruited about fifty men to serve as Apache Scouts. These men would play a key role in the success of the Army in the Apache Wars which ensued for the next 15 years.

After recruiting the scouts, Crook prepared for his Tonto Basin campaign. Then he moved on to Camp Verde to implement his tactical operations there. During the winter of 1872-1873, Crook sent a number of mobile detachments, using Apache scouts, to crisscross the Tonto Basin and the surrounding tablelands in constant pursuit of renegade Tonto Apache and their Yavapai allies. The campaigns forcing as many as 20 skirmishes. In all some 200 Indians were killed. The battles finally began to wear down the Indians. On April 5, 1879, Camp

Apache had gained enough significance that it was renamed Fort Apache. The battles with the Apache continued as the soldiers fought various renegade bands that included such famous warriors as Geronimo, Natchez, Chato, and Chihuahua. It was only after Geronimo was captured for the last time in 1886, that the Apache Wars finally came to an end…and with it the need for Fort Apache. Nevertheless, it remained active until 1924. Then it was closed and the area given back to the reservation.

Apache had gained enough significance that it was renamed Fort Apache. The battles with the Apache continued as the soldiers fought various renegade bands that included such famous warriors as Geronimo, Natchez, Chato, and Chihuahua. It was only after Geronimo was captured for the last time in 1886, that the Apache Wars finally came to an end…and with it the need for Fort Apache. Nevertheless, it remained active until 1924. Then it was closed and the area given back to the reservation.

With new technology, always comes some risk of failure. Sometimes, the the failure doesn’t hurt anything, but other times, it can be deadly. In the world of submarines, the atomic submarine was the latest thing in the 1960s. The USS Thresher was launched on July 9, 1960, from Portsmouth Naval Yard in New Hampshire. It was built with the latest technology, and was the first submarine assembled as part of a new class that could run more quietly and dive deeper than any that had come before it. The designers and the Navy expected great things from Thresher, and initially, the submarine met their expectations.

With new technology, always comes some risk of failure. Sometimes, the the failure doesn’t hurt anything, but other times, it can be deadly. In the world of submarines, the atomic submarine was the latest thing in the 1960s. The USS Thresher was launched on July 9, 1960, from Portsmouth Naval Yard in New Hampshire. It was built with the latest technology, and was the first submarine assembled as part of a new class that could run more quietly and dive deeper than any that had come before it. The designers and the Navy expected great things from Thresher, and initially, the submarine met their expectations.

Then on April 10, 1963, at just before 8am, the Thresher was conducting drills off the coast of Cape Cod. At 9:13am, the USS Skylark, another ship participating in the drills, received a communication from the Thresher that the sub was experiencing  minor problems. Unfortunately, the minor problems turned into a very major problem…almost instantly. Other attempted communications with Thresher failed and, only five minutes later, sonar images showed the Thresher breaking apart as it fell to the bottom of the sea, 300 miles off the coast of New England. Sixteen officers, 96 sailors and 17 civilians were on board. All were killed.

minor problems. Unfortunately, the minor problems turned into a very major problem…almost instantly. Other attempted communications with Thresher failed and, only five minutes later, sonar images showed the Thresher breaking apart as it fell to the bottom of the sea, 300 miles off the coast of New England. Sixteen officers, 96 sailors and 17 civilians were on board. All were killed.

On April 12, President John F. Kennedy ordered that flags across the country be flown at half-staff to commemorate the lives lost in this disaster. A subsequent investigation revealed that a leak in a silver-brazed joint in the engine room had caused a short circuit in critical electrical systems. The problems quickly spread, making the equipment needed to bring the Thresher to the surface inoperable. The submarine went into a freefall to the bottom. There was no time to do anything to stop it or find a way of escape…if one existed.

The disaster forced improvements in the design and quality control of submarines. Twenty-five years later, in 1988, Vice Admiral Bruce Demars, the Navy’s chief submarine officer, said “The loss of Thresher initiated fundamental changes in the way we do business–changes in design, construction, inspections, safety checks, tests, and more. We have not forgotten the lessons learned. It’s a much safer submarine force today.” I don’t think there was necessarily anything that was done so wrong that it could have prevented what happened, but I could be wrong. Obviously, there is always room for improvement in any design, but unfortunately, sometimes the only way to know that an improvement is needed, is to have a disaster strike.

When I talked to my dad about his time at Great Ashfield in Suffolk, England, we talked about, among other things, the sign at the town entrance that still stands today, after all these years since the end of World War II. The picture of the B-17G Bomber flying low over the town is not something that would necessarily be well received these days, when people are so quick to complain about the planes when they live near an airport. I understand why people would not like planes flying low on takeoffs and landings these days, but the planes that fly over my house really don’t bother me at all. Nevertheless, my dad assured me that the people of Great Ashfield felt anything but irritation at the low flying planes that graced their skies during World War II.

When I talked to my dad about his time at Great Ashfield in Suffolk, England, we talked about, among other things, the sign at the town entrance that still stands today, after all these years since the end of World War II. The picture of the B-17G Bomber flying low over the town is not something that would necessarily be well received these days, when people are so quick to complain about the planes when they live near an airport. I understand why people would not like planes flying low on takeoffs and landings these days, but the planes that fly over my house really don’t bother me at all. Nevertheless, my dad assured me that the people of Great Ashfield felt anything but irritation at the low flying planes that graced their skies during World War II.

England was among the nations who had taken some serious hits by the Nazi war machine in the early days of World War II, prior to the entrance of the United States into the war. In fact, it was on this day, December 29, 1940 that London took a massive hit during a German raid. The German planes had been targeting London since August of 1940 as payback for the British attacks on Berlin. In September the Germans dropped 337 tons of bombs on docks, tenements, and the streets in one of London’s poorest districts. Then came December 29, 1940. The attack on that day produced widespread destruction of not just civilians, but also many of London’s cultural relics. The bombing was relentless and as a result, 15,000 separate fires were started. Historic buildings were severely damaged or destroyed. Among them, the Guildhall, which was an administrative center of the city  that dated back to 1673, but contained a 15th century vault. Eight Christopher Wren churches were also damaged or destroyed. St Paul’s Cathedral caught fire, but was saved by the firefighters who risked their own lives to save it. Westminster Abbey, Buckingham Palace and the Chamber of the House of Commons were also hit, but the damage to these was less severe. These attacks, that went on from September of 1940 through May of 1940, were known as the London Blitz, and they killed thousands of civilians.

that dated back to 1673, but contained a 15th century vault. Eight Christopher Wren churches were also damaged or destroyed. St Paul’s Cathedral caught fire, but was saved by the firefighters who risked their own lives to save it. Westminster Abbey, Buckingham Palace and the Chamber of the House of Commons were also hit, but the damage to these was less severe. These attacks, that went on from September of 1940 through May of 1940, were known as the London Blitz, and they killed thousands of civilians.

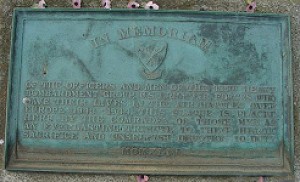

It wasn’t until Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, that the United States entered World War II, and soon after came the time that my dad spent at Great Ashfield beginning in early April of 1944 until he went home in October of 1945. While it may have seemed to many that we were somewhat late coming to the party, the war torn nations around the world were happy to see us arrive. It wasn’t that we were going to be the heroes riding in on the white horses, but we meant instant reinforcements to nations that needed assistance badly. The airmen were well received in the towns surrounding Great Ashfield, and the other air bases in England, but it was Great Ashfield that felt such gratitude that they went to the length of making and leaving to this day, the sign showing the B-17G Bomber flying low over the local church. There is also another memorial honoring the men of the 8th Air Force and the 385th Heavy Bombardment Group.

The reasons for the warm feelings toward the 8th Air Force and the 385th Heavy Bombardment Group are obvious. It was so much more than just the reinforcements the United States provided. While talking to my

dad about this, he revealed that the main reason that they were so grateful is that the safest times for the area were when the B-17G Bombers were flying overhead. The German aircraft would become really scarce when the Bombers were around, because they didn’t want to be shot down either. The constant activity surrounding the air field made it almost impossible for the Germans to attack the area. Bombings are horrible, and take a huge toll on the civilians, as well as buildings. I suppose I would be eternally grateful for those planes, those men, and the United States 8th Air Force too. It gave peace of mind.

dad about this, he revealed that the main reason that they were so grateful is that the safest times for the area were when the B-17G Bombers were flying overhead. The German aircraft would become really scarce when the Bombers were around, because they didn’t want to be shot down either. The constant activity surrounding the air field made it almost impossible for the Germans to attack the area. Bombings are horrible, and take a huge toll on the civilians, as well as buildings. I suppose I would be eternally grateful for those planes, those men, and the United States 8th Air Force too. It gave peace of mind.

I have been reading through some of my dad’s letters home to his family from World War II, and I find myself thinking about the secrets that had to be kept. During wartime, locations and mission cannot be spoken of, because it might, or more likely would, compromise the mission and the men involved. I’m sure it was hard for the men, when they couldn’t tell their families where they were, other than the country they were in. Still, they knew that what they were doing was bigger than they were, and they were a part of something greater than their own needs…and there were spies everywhere. Letters and calls could be intercepted, and if they were, missions could fail, and lives would be lost.

I have been reading through some of my dad’s letters home to his family from World War II, and I find myself thinking about the secrets that had to be kept. During wartime, locations and mission cannot be spoken of, because it might, or more likely would, compromise the mission and the men involved. I’m sure it was hard for the men, when they couldn’t tell their families where they were, other than the country they were in. Still, they knew that what they were doing was bigger than they were, and they were a part of something greater than their own needs…and there were spies everywhere. Letters and calls could be intercepted, and if they were, missions could fail, and lives would be lost.

Mixed in with the necessity of secrecy, was the need to let family know you were ok. Remember, that most of these men were very young, and many had never been away from home before. Now on that first trip away from home, there are people trying to kill them. My dad had lived away from home before going into the Army Air Forces, but he was very loving and loyal toward his family. It was very important to him that they not worry about him. Dad was also an honorable man. He was a patriot. He would never do anything that would dishonor or put in danger his country, or the men he served with. I can imagine that these men all found themselves in a tough place at that time in the world’s history, but they did what they had to do, because they were a part of something greater than their own feelings, or those of their families.

My dad was the top turret gunner and the flight engineer on a B17 Bomber, stationed at Great Ashfield, Suffolk, England. It was a base in the middle of the English countryside, surrounded by civilian towns and farms. These people knew all too well how important the United States military presence was to their safety, and indeed their very lives. If one of those men had revealed information about their upcoming missions, the entire area could have been attacked and destroyed. So important was their mission over there, and so grateful were the people of that area, that memorials were erected to remember…forever, the sacrifice made by the brave men of the 385th Heavy Bombardment Group, U.S. Army Air Forces. The memorials were placed so that generation, and future generations would remember the sacrifices made to save their lives by men who were a part of something greater than their own lives…to protect the lives of people they didn’t  even know. That is what my dad was a part of when he was barely more than a teenager.

even know. That is what my dad was a part of when he was barely more than a teenager.

Those years changed who my dad was, just like they changed the lives of all the men who lived through that turbulent time in the history of the world. Those were hard times for everyone, and yet my dad and the other young men he served with, played their very important part with dignity and honor, placing the lives of innocent civilians ahead of their own lives, because they were a part of something greater.