citizens

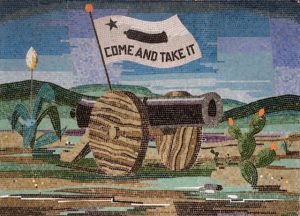

Since the 17th century, Texas, or Tejas as the Mexicans called it, had technically been a part of the Spanish empire. However, there were only about 3,000 Spanish-Mexican settlers in Texas, even as late as the 1820s, and Mexico City’s hold on the territory was very weak. Tensions were growing between Mexico and Texas, and on October 2, 1835, the area erupted into violence when Mexican soldiers attempted to disarm the people of Gonzales. People just don’t take kindly to having their guns taken away in any era, I guess. The citizens of Texas chose a war for independence of allowing the government to take their guns.

Since the 17th century, Texas, or Tejas as the Mexicans called it, had technically been a part of the Spanish empire. However, there were only about 3,000 Spanish-Mexican settlers in Texas, even as late as the 1820s, and Mexico City’s hold on the territory was very weak. Tensions were growing between Mexico and Texas, and on October 2, 1835, the area erupted into violence when Mexican soldiers attempted to disarm the people of Gonzales. People just don’t take kindly to having their guns taken away in any era, I guess. The citizens of Texas chose a war for independence of allowing the government to take their guns.

Mexico had just won it’s own independence from Spain in 1821. At this point, Mexico welcomed large numbers of Anglo-American immigrants into Texas. They were hoping that these citizens would become loyal Mexican citizens, thereby keeping the territory from falling into the hands of the United States. During the next decade men like Stephen Austin brought more than 25,000 people to Texas, most of them Americans. But while these emigrants legally became Mexican citizens, they continued to speak English, formed their own schools, and had closer trading ties to the United States than to Mexico.

The situation exacerbated in 1835, the president of Mexico, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, overthrew the constitution and appointed himself dictator. Recognizing that the “American” Texans were likely to use his rise to power as an excuse to secede, Santa Anna ordered the Mexican military to begin disarming the Texans whenever possible. He underestimated the people. His attempt to disarm proved more difficult than he could have ever imagined, and the situation exploded on that October day in 1835.

That day, the Mexican soldiers were attempting to take a small cannon from the village of Gonzales. To their surprise, they encountered much stiffer resistance than they ever thought possible from a hastily assembled militia of Texans. After a rather brief fight, the Mexicans retreated and the Texans kept their cannon. The determined Texans would continue to battle Santa Ana and his army for another year and a half before winning their independence and establishing the Republic of Texas. This truly goes to show that a nation, whose citizens are armed, is much more likely to be able to fend off their enemies…even if that enemy is a tyrannous government; than an nation of disarmed citizens. Yes, the ensuing war lasted for another year and a half, but

the people won their independence in the end. They later went on to become a part of the United States, and they continue to carry their guns to this day. The people of Texas are just as adamant about their right to bear arms today as they were in 1835, as are a good number of their fellow Americans. It’s a fight that would not likely be won by the government today either. The American people won’t accept the loss of guns without a fight of epic proportions!!

the people won their independence in the end. They later went on to become a part of the United States, and they continue to carry their guns to this day. The people of Texas are just as adamant about their right to bear arms today as they were in 1835, as are a good number of their fellow Americans. It’s a fight that would not likely be won by the government today either. The American people won’t accept the loss of guns without a fight of epic proportions!!

Most people would agree that the prospect of taking a nation into war is a scary one at best…especially for its citizens. In 1916, the world was in the middle of World War I. Isolationism had been the order of the day, as the United States tried to stay out of this war, but by the summer of 1916, with the Great War raging in Europe, and with the United States and other neutral ships threatened by German submarine aggression, it had become clear to many in the United States that their country could no longer stand on the sidelines. With that in mind, some of the leading business figures in San Francisco planned a parade in honor of American military preparedness. The day was dubbed Preparedness Day, and with the isolationist, anti-war, and anti-preparedness feeling that still ran high among a significant population of the city…and the country, not only among such radical organizations as International Workers of the World (the so-called “Wobblies”) but among mainstream labor leaders. These opponents of the Preparedness Day event undoubtedly shared the view voiced publicly by one critic, former U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who claimed that the organizers, San Francisco’s financiers and factory owners, were acting in pure self-interest, as they clearly stood to benefit from an increased production of munitions. At the same time, with the rise of Bolshevism and labor unrest, San Francisco’s business community was justifiably nervous. The Chamber of Commerce organized a Law and Order Committee, despite the diminishing influence and political clout of local labor organizations. Radical labor was a small but vociferous minority which few took seriously. Nevertheless, it became obvious that violence was imminent.

Most people would agree that the prospect of taking a nation into war is a scary one at best…especially for its citizens. In 1916, the world was in the middle of World War I. Isolationism had been the order of the day, as the United States tried to stay out of this war, but by the summer of 1916, with the Great War raging in Europe, and with the United States and other neutral ships threatened by German submarine aggression, it had become clear to many in the United States that their country could no longer stand on the sidelines. With that in mind, some of the leading business figures in San Francisco planned a parade in honor of American military preparedness. The day was dubbed Preparedness Day, and with the isolationist, anti-war, and anti-preparedness feeling that still ran high among a significant population of the city…and the country, not only among such radical organizations as International Workers of the World (the so-called “Wobblies”) but among mainstream labor leaders. These opponents of the Preparedness Day event undoubtedly shared the view voiced publicly by one critic, former U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who claimed that the organizers, San Francisco’s financiers and factory owners, were acting in pure self-interest, as they clearly stood to benefit from an increased production of munitions. At the same time, with the rise of Bolshevism and labor unrest, San Francisco’s business community was justifiably nervous. The Chamber of Commerce organized a Law and Order Committee, despite the diminishing influence and political clout of local labor organizations. Radical labor was a small but vociferous minority which few took seriously. Nevertheless, it became obvious that violence was imminent.

A radical pamphlet of mid-July read in part, “We are going to use a little direct action on the 22nd to show that militarism can’t be forced on us and our children without a violent protest.” It was in this environment that the Preparedness Parade found itself on July 22, 1916. In spite of that, the 3½ hour long procession of some 51,329 marchers, including 52 bands and 2,134 organizations, comprising military, civic, judicial, state and municipal divisions as well as newspaper, telephone, telegraph and streetcar unions, went ahead as planned. At 2:06pm, about a half hour after the parade began, a bomb concealed in a suitcase exploded on the west side of Steuart Street, just south of Market Street, near the Ferry Building. Ten bystanders were killed by the explosion, and 40 more were wounded, in what became the worst terrorist act in San Francisco history. The city and the nation were outraged, and they declared that justice would be served.

Two radical labor leaders, Thomas Mooney and Warren K Billings, were quickly arrested and tried for the  attack. In the trial that followed, the two men were convicted, despite widespread belief that they had been framed by the prosecution. Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life in prison. After evidence surfaced as to the corrupt nature of the prosecution, President Woodrow Wilson called on California Governor William Stephens to look further into the case. Two weeks before Mooney’s scheduled execution, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, the same punishment Billings had received. Investigation into the case continued over the next two decades. By 1939, evidence of perjury and false testimony at the trial had so mounted that Governor Culbert Olson pardoned both men, and the true identity of the Preparedness Day bomber, or bombers, remains forever unknown.

attack. In the trial that followed, the two men were convicted, despite widespread belief that they had been framed by the prosecution. Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life in prison. After evidence surfaced as to the corrupt nature of the prosecution, President Woodrow Wilson called on California Governor William Stephens to look further into the case. Two weeks before Mooney’s scheduled execution, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, the same punishment Billings had received. Investigation into the case continued over the next two decades. By 1939, evidence of perjury and false testimony at the trial had so mounted that Governor Culbert Olson pardoned both men, and the true identity of the Preparedness Day bomber, or bombers, remains forever unknown.