chinese

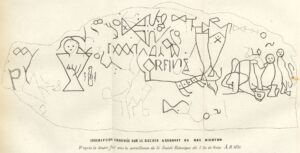

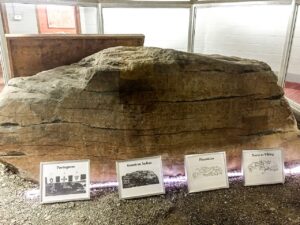

The Dighton Rock is a 40-ton boulder that was found in the riverbed of the Taunton River at located Berkley, Massachusetts, over 300 years ago. The rock has puzzling petroglyphs on it that have apparently never been able to be deciphered. Dighton Rock is one of the greatest mysteries of Massachusetts. The boulder is slanted and has six sides. It is approximately 5′ high, 9½’ wide, and 11′ long. All of those 300 years, people have wondered about the lines, geometric shapes, drawings, and writing that appear on the rock and who created them. They wanted to figure it out. What did it mean? Who made those markings, so many years ago. No one really knows how long ago the marks were made, only about how long ago it was found.

The Dighton Rock is a 40-ton boulder that was found in the riverbed of the Taunton River at located Berkley, Massachusetts, over 300 years ago. The rock has puzzling petroglyphs on it that have apparently never been able to be deciphered. Dighton Rock is one of the greatest mysteries of Massachusetts. The boulder is slanted and has six sides. It is approximately 5′ high, 9½’ wide, and 11′ long. All of those 300 years, people have wondered about the lines, geometric shapes, drawings, and writing that appear on the rock and who created them. They wanted to figure it out. What did it mean? Who made those markings, so many years ago. No one really knows how long ago the marks were made, only about how long ago it was found.

The rock has been studied by many people over the years. In 1680, English colonist Reverend John Danforth drew a copy of the petroglyphs. That drawing has been preserved in the British Museum, but there are conflicts as to the accuracy of the drawing. Some say the markings aren’t exactly the same as the rock. In something as intricate as petroglyphs, accuracy would be of vital importance. Ten years later, in 1690 Reverend Cotton Mather described the rock in his book, The Wonderful Works of God Commemorated: “Among the other Curiosities of New England, one is that of a mighty Rock, on a perpendicular side whereof by a River, which at High Tide covers part of it, there are very deeply Engraved, no man alive knows How or When about half a score Lines, near Ten Foot Long, and a foot and half broad, filled with strange Characters: which would suggest as odd Thoughts about them that were here before us, as there are odd Shapes in that Elaborate Monument…”

One theory suggests that Indigenous peoples of North America…who were known to have inscribed petroglyphs in rocks (a schematic face on the Dighton Rock is similar to an Indian petroglyph in Eastern Vermont) made the markings. A second theory suggests that Ancient Phoenicians made them was proposed in 1783 by Ezra Stiles in his “Election Sermon” as the “descendants of the sons of Japheth.” Still another theory suggests that the Norse might have made them. That theory was proposed by Carl Christian Rafn in 1837, but it was rejected by archaeologists such as TD Kendrick and Kenneth Feder. Others suggested that the Portuguese may have made them. That was proposed in 1912 by Edmund B Delabarre, who (after seeing Portuguese writing) believed that they then used the rock for their own inscriptions. Delabarre wrote that “markings on the Dighton Rock suggest that Miguel Corte-Real reached New England. Delabarre stated that the markings were abbreviated Latin, and the message, translated into English, reads as follows: “I, Miguel Cortereal, 1511. In this place, by the will of God, I became a chief of the Indians.'” Of his findings, Douglas Hunter wrote in his book “Reconstructing the

history of writing about Dighton Rock” provides copious evidence and analysis debunking the Corte-Real origin myth. Lastly, the Chinese have also been suggested as a possible source, proposed by Gavin Menzies in his 2002 book “1421: The Year China Discovered America.” I don’t think we’ll ever know who made them or what they mean.

history of writing about Dighton Rock” provides copious evidence and analysis debunking the Corte-Real origin myth. Lastly, the Chinese have also been suggested as a possible source, proposed by Gavin Menzies in his 2002 book “1421: The Year China Discovered America.” I don’t think we’ll ever know who made them or what they mean.

As children, most of us have been on the receiving end of a form of “torture” that really isn’t exactly torture for most of us, but rather just good clean fun…provided that the torturer knows when to stop. My sisters and I were among the experts of our era…at least four of us were. The fifth sister, the middle one, Caryl Reed, was an “accomplished” victim…not because she chose to be the victim, but rather that she was the one we most loved to tickle. She was just such a great victim!! We would tickle her until she could hardly breathe, and then we would show some “mercy” and let her “live to be victimized another day.”

As children, most of us have been on the receiving end of a form of “torture” that really isn’t exactly torture for most of us, but rather just good clean fun…provided that the torturer knows when to stop. My sisters and I were among the experts of our era…at least four of us were. The fifth sister, the middle one, Caryl Reed, was an “accomplished” victim…not because she chose to be the victim, but rather that she was the one we most loved to tickle. She was just such a great victim!! We would tickle her until she could hardly breathe, and then we would show some “mercy” and let her “live to be victimized another day.”

I always thought my sisters, Cheryl Masterson, Alena Stevens, Allyn Hadlock, and I were very clever at coming up with something totally new…the Tickle Torture, but it turns out that Tickle Torture is an ancient form of actual torture. Who knew? Certainly not my sisters or me. Our form of torture, barely resembles the ancient form, or the form that still exists to this day among military circles. As it turns out, the tickle torture began in 260 BC, as far as anyone can tell, when the Han Dynasty appears to have implemented the technique as a reliable punishment that didn’t leave marks. It was used by  both the Ancient Romans and the Chinese. I have heard of some of the brutal forms of torture that the Romans used, and I suppose at first this seemed like one of the most humane forms of torture in their entourage. It seems that they would apply salt on the soles of feet and then have a goat lick it off. If you have ever had an animal lick your hand, you know that they usually have a rough tongue. At first, the torture must have been crazy in an extremely ticklish sort of way, and very likely the victim laughed until they could hardly breathe. As the torture continued, the rough tongue of the goat began to actually cause extreme pain…sometimes even lacerating the skin of the feet. The Chinese used this torture on the nobility because there was little evidence left behind and recovery was quick.

both the Ancient Romans and the Chinese. I have heard of some of the brutal forms of torture that the Romans used, and I suppose at first this seemed like one of the most humane forms of torture in their entourage. It seems that they would apply salt on the soles of feet and then have a goat lick it off. If you have ever had an animal lick your hand, you know that they usually have a rough tongue. At first, the torture must have been crazy in an extremely ticklish sort of way, and very likely the victim laughed until they could hardly breathe. As the torture continued, the rough tongue of the goat began to actually cause extreme pain…sometimes even lacerating the skin of the feet. The Chinese used this torture on the nobility because there was little evidence left behind and recovery was quick.

People have mixed feelings on tickling. Some like it, but some don’t. I have always been of the mind that if someone really hates it, it should not be done. Of course, the victims in those days had no choice, and I doubt if anyone really liked that kind of tickle torture. I guess that if a person really hates the tickle torture, they might be able to understand how some groups in history have come up with ways to turn it into an actual form of torture. In the actual torture, people might pass out, vomit, and some even died…at least it went that far in the Nazi concentration camps during World War II. I suppose that for anyone who lived through any of that or knew someone who did, the tickle torture would not be funny at all. Still, tickle torture was not as bad as some  of the other forms of torture used in ancient times, nor was it often as deadly as those other forms.

of the other forms of torture used in ancient times, nor was it often as deadly as those other forms.

Actual Tickle torture is still in use today too, and not just in various households across the world. Special operations forces may actually use it in interrogations, as a method of non-lethal torture to be employed by governments to gain information from a suspect. I don’t know how they would actually get any information for a victim, unless their form of torture took a painful turn, but then I’m not an interrogator, so maybe they know something I don’t. What I do know is that my sisters and I had many happy sessions of applying the tickle torture to our sister, Caryl.

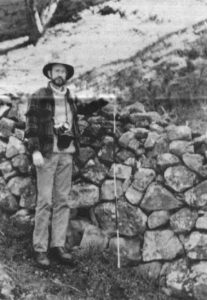

There is a wall that lots o people might have known about, or maybe few people know about, but while I’m sure I’ve seen parts of it in movies, I didn’t really know about it. The series of walls, known as the East Bay Walls or the Berkeley Mystery Walls. Of course that doesn’t really apply to one area, because the reality is that there are many of the crude walls throughout the hills surrounding the San Francisco Bay area. In some place the walls are as much as 3 feet tall, and 3 feet wide. The walls are very old and they were built without mortar. The walls run in sections, and they can be a few feet to over a mile long. Even more odd, is the fact that the rocks are a variety of sizes ranging from basketball-sized rocks, to large sandstone boulders weighing a ton or more. Parts of the walls seem to be just piles of rocks, but in other places it appears the walls were carefully constructed. No one knows the exact age of the walls, but they have an old appearance. Many of the formations have sunk far into the earth, and are often completely overgrown with different plants. The walls are not continuous, so they are not fences. They are not tall enough to have been used as defensive walls. The East Bay Regional Park District simply calls them “rock walls” and insists that they are not mysterious. Livestock, such as cattle, have grazed in the east and south Bay Area hills since the arrival of European

There is a wall that lots o people might have known about, or maybe few people know about, but while I’m sure I’ve seen parts of it in movies, I didn’t really know about it. The series of walls, known as the East Bay Walls or the Berkeley Mystery Walls. Of course that doesn’t really apply to one area, because the reality is that there are many of the crude walls throughout the hills surrounding the San Francisco Bay area. In some place the walls are as much as 3 feet tall, and 3 feet wide. The walls are very old and they were built without mortar. The walls run in sections, and they can be a few feet to over a mile long. Even more odd, is the fact that the rocks are a variety of sizes ranging from basketball-sized rocks, to large sandstone boulders weighing a ton or more. Parts of the walls seem to be just piles of rocks, but in other places it appears the walls were carefully constructed. No one knows the exact age of the walls, but they have an old appearance. Many of the formations have sunk far into the earth, and are often completely overgrown with different plants. The walls are not continuous, so they are not fences. They are not tall enough to have been used as defensive walls. The East Bay Regional Park District simply calls them “rock walls” and insists that they are not mysterious. Livestock, such as cattle, have grazed in the east and south Bay Area hills since the arrival of European  settlers. Clearing land of scattered rocks would have eased the ability to move livestock. Placing the rocks into walls would have helped to guide the movement of the animals or to help corral them. That makes sense, but some of those rocks were very heavy. So how did they do that.

settlers. Clearing land of scattered rocks would have eased the ability to move livestock. Placing the rocks into walls would have helped to guide the movement of the animals or to help corral them. That makes sense, but some of those rocks were very heavy. So how did they do that.

There is no written documentation to identify when they were built, by whom, or why. So, some people consider them mysterious. It has been suggested that the Ohlone Indians might have been the builders, but in reality, they were hunter-gatherers, and didn’t build permanent structures. Some specialists have mentioned that the walls look similar to structures found in rural Massachusetts, Vermont, and Maine, but they are different in that those walls were built around farms by the early setters, and these don’t have the same kinds of layouts. In 1904, UC-Berkeley Professor John Fryer suggested that the walls were made by Mongolian Chinese who traveled to California before the Europeans. Unfortunately, there is little evidence for this or for pre-Columbian Chinese influence in America. Forensic geologist Scott Wolter has theorized that the wall is only two to three hundred years old, suggested by the thick weathering rind on the limestone rock he was authorized to sample. Recent testing of lichen on the rocks suggests that they were probably built between 1850 and 1880, the early American era in California. Settlers might have built the walls using Chinese, Mexican, or Native American laborers, although specifically who built them has not been determined.

One of the many old stone walls that appear around the San Francisco Bay area is in the foothills of eastern  Santa Clara County. The stone walls are accessible in several area parks, including Ed R. Levin County Park in Santa Clara County and Mission Peak Regional Preserve in Alameda County, as well as many other parks. As of 2016, archaeologist Jeffrey Fentress has been measuring and mapping the walls, hoping to eventually gain protection from development or other destruction. Additional stone walls with unclear origin or purpose occur in other places near the San Francisco Bay, and researchers continue to discover more information about the walls. Whether these walls had a purpose at one time or not, they are certainly strange to those who try to look into them these days.

Santa Clara County. The stone walls are accessible in several area parks, including Ed R. Levin County Park in Santa Clara County and Mission Peak Regional Preserve in Alameda County, as well as many other parks. As of 2016, archaeologist Jeffrey Fentress has been measuring and mapping the walls, hoping to eventually gain protection from development or other destruction. Additional stone walls with unclear origin or purpose occur in other places near the San Francisco Bay, and researchers continue to discover more information about the walls. Whether these walls had a purpose at one time or not, they are certainly strange to those who try to look into them these days.

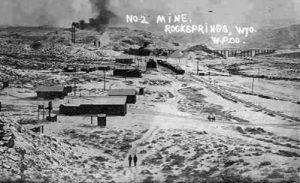

In 1885, coal miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory were trying to unionize, and were trying to strike for better working conditions, but the Union Pacific Railroad company had been besting them in their efforts for a long time. In those days, the companies often had the advantage over the workers. Working conditions suffered as a result of this disadvantage. Unions and companies were constantly at odds, for obvious reasons. I suppose that in any business, there are good and bad people. Sometimes, when people come into power in an organization, corruption follows. The companies of that time didn’t want to do what was necessary to make working in the mines safe, and as most people know, underground mining can be a very dangerous occupation. The chance of cave ins or explosions exists in even the safest mines, as well as having poisonous gasses leaking into the limited air supply, bringing death to the miners.

In 1885, coal miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory were trying to unionize, and were trying to strike for better working conditions, but the Union Pacific Railroad company had been besting them in their efforts for a long time. In those days, the companies often had the advantage over the workers. Working conditions suffered as a result of this disadvantage. Unions and companies were constantly at odds, for obvious reasons. I suppose that in any business, there are good and bad people. Sometimes, when people come into power in an organization, corruption follows. The companies of that time didn’t want to do what was necessary to make working in the mines safe, and as most people know, underground mining can be a very dangerous occupation. The chance of cave ins or explosions exists in even the safest mines, as well as having poisonous gasses leaking into the limited air supply, bringing death to the miners.

The situation took a deadly turn on September 2, 1885, when 150 white miners brutally attacked their Chinese coworkers, killing 28 and wounding 11 others, while driving several others out of town. The Chinese weren’t really the problem, except that they were hard workers, and so the company had initially decided to bring them in as strikebreakers. The Chinese workers showed very little interest in the miners’ union, and I’m sure this  made the rest of the miners very angry. The miners became outraged by a company decision to allow the Chinese miners to work in the richest coal mines, and before long, the situation turned into a mob of white miners deciding to strike back by attacking the small area of Rock Springs known as Chinatown.

made the rest of the miners very angry. The miners became outraged by a company decision to allow the Chinese miners to work in the richest coal mines, and before long, the situation turned into a mob of white miners deciding to strike back by attacking the small area of Rock Springs known as Chinatown.

When the Chinese saw the white miners coming, most of them abandoned their homes and business, running for the hills. Those who failed to get out in time were brutally beaten, and 28 of them, beaten to death. One week later, on September 9, United States troops escorted the surviving Chinese back into the town where many of them returned to work. I guess they were either very loyal, desperate for the money, or had no other real choices, because I can’t imagine going back to work in that situation. Eventually the Union Pacific fired 45 of the white miners for their roles in the massacre, but no effective legal action was ever taken against any of the participants…no repercussion for the brutal murder of 28 Chinese men.

I wound never agree with murder, but it was also wrong to use the Chinese in this way. By bringing them in as strikebreakers, the Union Pacific Railroad effectively caused the anti-Chinese sentiment that was shared by  many, and began to come to the West in the mid-nineteenth century, fleeing famine and political upheaval in their own country. The Chinese were many Americans at that time. The Chinese had been victims of prejudice and violence ever since they first widely blamed for all sorts of social ills. They were also singled-out for attack by some national politicians who popularized strident slogans like “The Chinese Must Go” and helped pass an 1882 law that closed the United States to any further Chinese immigration. The Rock Springs massacre was just another symptom in this climate of racial hatred, violent attacks against the Chinese in the West became all too common. But, the Rock Springs massacre was the worst, both for its size and savage brutality.

many, and began to come to the West in the mid-nineteenth century, fleeing famine and political upheaval in their own country. The Chinese were many Americans at that time. The Chinese had been victims of prejudice and violence ever since they first widely blamed for all sorts of social ills. They were also singled-out for attack by some national politicians who popularized strident slogans like “The Chinese Must Go” and helped pass an 1882 law that closed the United States to any further Chinese immigration. The Rock Springs massacre was just another symptom in this climate of racial hatred, violent attacks against the Chinese in the West became all too common. But, the Rock Springs massacre was the worst, both for its size and savage brutality.