catholic

Religious beliefs have caused a number of issues in governments over the centuries, sometimes pitting family members against family members. They were, in fact, the main reason that the United States was founded…to get away from religious persecution. Such was also the case in the coup that was called Britain’s Bloodless Glorious Revolution. At the time, King James II was the king in Britain, and he was a Catholic. At first that didn’t seem like a huge problem, but King James’s policies of religious tolerance after 1685 began to meet with increasing opposition from members of leading political circles, who were troubled by the King’s Catholicism and his close ties with France. The crisis facing the King came to a head in 1688, with the birth of his son, James Francis Edward Stuart, on June 10. This changed the existing line of succession by displacing the heir presumptive, his daughter Mary, a Protestant and the wife of William of Orange, with young James Francis Edward as heir apparent, because at that time it was the first born “son” who inherited the throne. The establishment of a Roman Catholic dynasty in the kingdoms now seemed likely, and the people weren’t happy about it.

Religious beliefs have caused a number of issues in governments over the centuries, sometimes pitting family members against family members. They were, in fact, the main reason that the United States was founded…to get away from religious persecution. Such was also the case in the coup that was called Britain’s Bloodless Glorious Revolution. At the time, King James II was the king in Britain, and he was a Catholic. At first that didn’t seem like a huge problem, but King James’s policies of religious tolerance after 1685 began to meet with increasing opposition from members of leading political circles, who were troubled by the King’s Catholicism and his close ties with France. The crisis facing the King came to a head in 1688, with the birth of his son, James Francis Edward Stuart, on June 10. This changed the existing line of succession by displacing the heir presumptive, his daughter Mary, a Protestant and the wife of William of Orange, with young James Francis Edward as heir apparent, because at that time it was the first born “son” who inherited the throne. The establishment of a Roman Catholic dynasty in the kingdoms now seemed likely, and the people weren’t happy about it.

Some Tory (conservative) members of parliament worked with members of the opposition Whigs in an attempt to resolve the crisis by secretly initiating dialogue with William of Orange to come to England…outside the jurisdiction of the English Parliament. Stadtholder William, the de facto head of state of the Dutch United Provinces, feared a Catholic Anglo–French alliance and had already been planning a military intervention in England, so he was very much open to the plan. After consolidating political and financial support, William crossed the North Sea and English Channel with a large invasion fleet in November 1688, landing at Torbay in Devonshire with an army of 15,000 men, William advanced to London, meeting no opposition from James’ army, which had deserted the king. After only two minor clashes between the two opposing armies in England, and anti-Catholic riots in several towns, King James’s regime collapsed, largely because of a lack of resolve shown by the king. Following Britain’s Bloodless Glorious Revolution, Mary, the daughter of the deposed king, and William of Orange, her husband, are proclaimed joint sovereigns of Great Britain under Britain’s new Bill of Rights. At first I thought that odd, because by rights she would have been in the royal line, but I suppose you would have to honor the warrior who made it all possible.

King James was allowed to escape to France, and in February 1689 Parliament offered the crown jointly to  William and Mary, provided they accept the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights, which greatly limited royal power and broadened constitutional law, granted Parliament control of finances and the army and prescribed the future line of royal succession, declaring that no Roman Catholic would ever be sovereign of England. The document also stated that Englishmen possessed certain inviolable civil and political rights, a political concept that was a major influence in the composition of the United States Bill of Rights, composed almost exactly a century later. The Glorious Revolution, the ascension of William and Mary, and the acceptance of the Bill of Rights were decisive victories for Parliament in its long struggle against the crown.

William and Mary, provided they accept the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights, which greatly limited royal power and broadened constitutional law, granted Parliament control of finances and the army and prescribed the future line of royal succession, declaring that no Roman Catholic would ever be sovereign of England. The document also stated that Englishmen possessed certain inviolable civil and political rights, a political concept that was a major influence in the composition of the United States Bill of Rights, composed almost exactly a century later. The Glorious Revolution, the ascension of William and Mary, and the acceptance of the Bill of Rights were decisive victories for Parliament in its long struggle against the crown.

Because my family has some history in England and Ireland, the history of that area holds an interest for me. Through my DNA, I have found out that much of the family I previously thought of as English, actually originated in France. Nevertheless, they spent the majority of the centuries in England and Ireland. That said, the feuds between the two nations have been as interesting to me as the Revolutionary War. I suppose that when a nation turns an area into a territory, and then that area decides to become it’s own nation, there can be a bit of an uproar…to put it mildly. The parent nation is usually very much against the independence of the child nation…for lack of a better word.

Because my family has some history in England and Ireland, the history of that area holds an interest for me. Through my DNA, I have found out that much of the family I previously thought of as English, actually originated in France. Nevertheless, they spent the majority of the centuries in England and Ireland. That said, the feuds between the two nations have been as interesting to me as the Revolutionary War. I suppose that when a nation turns an area into a territory, and then that area decides to become it’s own nation, there can be a bit of an uproar…to put it mildly. The parent nation is usually very much against the independence of the child nation…for lack of a better word.

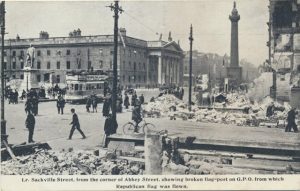

It was on April 24, 1916…Easter Monday, that the Irish Republican Brotherhood, which was a secret organization of Irish nationalists led by Patrick Pearse, launched the so-called Easter Rebellion in Dublin. It was an armed uprising against British rule. The Brotherhood was assisted by militant Irish socialists under James Connolly. Pearse and his fellow Republicans rioted and attacked British provincial government headquarters across Dublin and seized the Irish capital’s General Post Office. After their quick initial success, they proclaimed the independence of Ireland, and by morning they controlled much of the city of Dublin. They were fighting against the repressive government of the United Kingdom that they had been under for centuries. Their hopes of freedom were dashed later the next day when the British authorities launched a counterattack. By April 29th, it was all over. The uprising had been crushed. Nevertheless, the Easter Rebellion is considered a significant marker on the road to establishing an independent Irish republic.

Following the uprising, Pearse and 14 other nationalist leaders were executed for their participation, but they were held up as martyrs by many in Ireland. There was a lot of anger among most Irish people for the British, who had enacted a series of harsh anti-Catholic restrictions, the Penal Laws, in the 18th century, and then let 1.5 million Irish starve during the Potato Famine of 1845-1848. Armed protest continued after the Easter Rebellion and in 1921, 26 of Ireland’s 32 counties won independence with the declaration of the Irish Free State. The Free State became an independent republic in 1949. However, six northeastern counties of the Emerald Isle remained part of the United Kingdom. This prompted some nationalists to reorganize themselves into the Irish Republican Army (IRA) to continue their struggle for full Irish independence.

In the late 1960s, spurred on in part by the United States civil rights movement, Catholics in Northern Ireland, who had long been discriminated against by British policies that favored Irish Protestants, advocated for justice. Riots broke out between Catholics and Protestants in the region and the violence escalated as the pro-Catholic IRA battled British troops. Most people have heard about this struggle over the years. An ongoing series of terrorist bombings and attacks ensued in a drawn-out conflict that came to be known as “The Troubles.” Peace talks

eventually took place throughout the mid to late 1990s, but a permanent end to the violence remained elusive, until July 2005, when IRA finally announced that its members would give up all their weapons and would pursue the group’s objectives solely through peaceful means. By the fall of 2006, the Independent Monitoring Commission reported that the IRA’s military campaign to end British rule was over.

eventually took place throughout the mid to late 1990s, but a permanent end to the violence remained elusive, until July 2005, when IRA finally announced that its members would give up all their weapons and would pursue the group’s objectives solely through peaceful means. By the fall of 2006, the Independent Monitoring Commission reported that the IRA’s military campaign to end British rule was over.