Caryn’s Thoughts

It seemed like a simple matter of a choice. Juliane Margaret Beate Koepcke, who was born on October 10, 1954, was set to graduate in Lima, Peru on December 23, 1971, and she wanted to attend her graduation ceremony before flying home to Panguana with her mother, Maria Koepcke. Juliane the only child of German zoologists Maria (née von Mikulicz-Radecki; 1924–1971) Maria and Hans-Wilhelm Koepcke (1914–2000). Her parents were working at Lima’s Museum of Natural History when she was born. When Juliane was 14, the family left Lima to establish the Panguana research station in the Amazon rainforest, where she learned survival skills. Unfortunately, the educational authorities didn’t allow this type of “schooling” and she was required to return to the Deutsche Schule Lima Alexander von Humboldt to take her exams and graduate. Maria really wanted to leave on December 19th or 20th, but she finally agreed that her daughter could stay longer. So, they scheduled a flight for Christmas Eve. All the flights were booked except for one with LANSA, an airline that Juliane’s father, Hans-Wilhelm had urged his wife to avoid flying with due to its poor reputation. Disregarding the warning, Maria booked tickets on LANSA flight 508.

It seemed like a simple matter of a choice. Juliane Margaret Beate Koepcke, who was born on October 10, 1954, was set to graduate in Lima, Peru on December 23, 1971, and she wanted to attend her graduation ceremony before flying home to Panguana with her mother, Maria Koepcke. Juliane the only child of German zoologists Maria (née von Mikulicz-Radecki; 1924–1971) Maria and Hans-Wilhelm Koepcke (1914–2000). Her parents were working at Lima’s Museum of Natural History when she was born. When Juliane was 14, the family left Lima to establish the Panguana research station in the Amazon rainforest, where she learned survival skills. Unfortunately, the educational authorities didn’t allow this type of “schooling” and she was required to return to the Deutsche Schule Lima Alexander von Humboldt to take her exams and graduate. Maria really wanted to leave on December 19th or 20th, but she finally agreed that her daughter could stay longer. So, they scheduled a flight for Christmas Eve. All the flights were booked except for one with LANSA, an airline that Juliane’s father, Hans-Wilhelm had urged his wife to avoid flying with due to its poor reputation. Disregarding the warning, Maria booked tickets on LANSA flight 508.

Mid-way through the flight, the plane was struck by lightning. The plane actually began to disintegrate before plummeting to the ground. Suddenly, Juliane found herself, still strapped to her seat, falling 10,000 feet into the Amazon rainforest. Amazingly, she survived the fall, but she was injured. She suffered a broken collarbone, a deep cut on her right arm, an eye injury, and a concussion. Juliane then spent 11 days in the rainforest, most of which were spent making her way through water by following a creek to a river. Apparently, no one knew  that she was there, or that she was missing from the wreckage of the plane. The jungle is a very unforgiving place for those without some kind of protection, and Juliane found herself dealing with severe insect bites and an infestation of maggots in her wounded arm. I’m sure that she could not believe that after surviving a fall of 10,000 feet, she might die in the jungle from whatever animal or insect might attack her. Nine days into her ordeal, she came upon an encampment that had been set up by local fishermen. There, she was able to at least give herself basic first aid. It was crude, however, and included pouring gasoline on her arm to force the maggots out of the wound. Then, she waited. After a few hours, the returning fishermen found her, gave her proper first aid, and used a canoe to transport her to a more inhabited area. Finally, she was soon airlifted to a hospital.

that she was there, or that she was missing from the wreckage of the plane. The jungle is a very unforgiving place for those without some kind of protection, and Juliane found herself dealing with severe insect bites and an infestation of maggots in her wounded arm. I’m sure that she could not believe that after surviving a fall of 10,000 feet, she might die in the jungle from whatever animal or insect might attack her. Nine days into her ordeal, she came upon an encampment that had been set up by local fishermen. There, she was able to at least give herself basic first aid. It was crude, however, and included pouring gasoline on her arm to force the maggots out of the wound. Then, she waited. After a few hours, the returning fishermen found her, gave her proper first aid, and used a canoe to transport her to a more inhabited area. Finally, she was soon airlifted to a hospital.

Many experts have tried to speculate as to how Juliane could have possibly survived. Some said that she survived the fall because she was harnessed into her seat, the window seat, which was attached to the two seats to her left as part of a row of three. They thought that somehow that functioned as a sort of parachute which slowed her fall. Some thought that the impact may have also been lessened by the updraft from a thunderstorm Koepcke fell through, as well as the thick foliage at her landing site. Juliane wasn’t the only passenger to have survived the initial disaster. Approximately 14 other passengers were later discovered to have survived the initial crash, but sadly, all of those died while waiting to be rescued. After recovering from her injuries, Koepcke assisted search parties in locating the crash site and recovering the bodies of victims. Her mother’s body was discovered on January 12, 1972. Juliane says, “I had nightmares for a long time, for years, and of course the grief about my mother’s death and that of the other people came back again and again. The thought ‘why was I the only survivor?’ haunts me. It always will.”

Juliane returned to her parents’ native Germany, where she fully recovered from her physical injuries. Like her parents, she studied biology at the University of Kiel and graduated in 1980. She received a doctorate from Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and returned to Peru to conduct research in mammalogy, specializing in bats. She published her thesis, “Ecological study of a bat colony in the tropical rain forest of Peru”, in 1987. In  1989, Koepcke married Erich Diller, a German entomologist who specializes in parasitic wasps. After her father died in 2000, she took over as the director of Panguana. Today, she serves as librarian at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology in Munich. Juliane’s autobiography “Als ich vom Himmel fiel: Wie mir der Dschungel mein Leben zurückgab” (German for When I Fell from the Sky: How the Jungle Gave Me My Life Back) was released in 2011. The book won that year’s Corine Literature Prize. In 2019, the government of Peru made her a Grand Officer of the Order of Merit for Distinguished Services.

1989, Koepcke married Erich Diller, a German entomologist who specializes in parasitic wasps. After her father died in 2000, she took over as the director of Panguana. Today, she serves as librarian at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology in Munich. Juliane’s autobiography “Als ich vom Himmel fiel: Wie mir der Dschungel mein Leben zurückgab” (German for When I Fell from the Sky: How the Jungle Gave Me My Life Back) was released in 2011. The book won that year’s Corine Literature Prize. In 2019, the government of Peru made her a Grand Officer of the Order of Merit for Distinguished Services.

Southend Pier, is the longest pier in the world. It is located in Southend-On-Sea, Essex, United Kingdom. It is famous for being the longest pier, but it is also famous for something else. It has a long history of…fires!! It wasn’t that there were so many fires, but rather that they occurred over a long period…40 years to be exact. That might not sound like such a big deal, which while sounding like a long period of time, is still rather unusual. The fires on the pier took place in 1959, 1976, 1995, and 2005.

Southend Pier, is the longest pier in the world. It is located in Southend-On-Sea, Essex, United Kingdom. It is famous for being the longest pier, but it is also famous for something else. It has a long history of…fires!! It wasn’t that there were so many fires, but rather that they occurred over a long period…40 years to be exact. That might not sound like such a big deal, which while sounding like a long period of time, is still rather unusual. The fires on the pier took place in 1959, 1976, 1995, and 2005.

Originally, the pier was really no more than a timber jetty. Then in 1829, a was passed to build the new pier. The bill received Royal Assent in May 1829 and construction started in July 1829. The original wooden pier that was finished in 1830, was just 600 feet long and probably nothing that could be considered spectacular. Over the years, the pier has evolved into an iron construction over a mile and a third in length. The history of the pier dating back well over a century, was one of developing facilities and increasing use by holidaymakers, with the exception of the World War II years. From 1939 to 1945 the pier was designated HMS Leigh and used as a mustering point for convoys and the location of Thames Estuary naval control staff.

All was going well, and then on October 7, 1959, disaster struck. In the evening a fire began in the Victorian pavilion towards the shore end of the pier. That part of the pier, a wooden structure went up like dried grass. At the time, there were between 300 and 500 visitors who were at the far end of the pier more than a mile away from the pavilion. It was a scary situation, because the visitors were required to walk toward the flames and then descend into waiting boats to be ferried back to the shore, bypassing the blaze. Of course, like any such incident, onlookers were provided with more than two hours of free entertainment, and since the pier was a popular attraction, there was a large crowd on the shore.

Because the pier was such a popular attraction, it was quickly repaired, and the pavilion was replaced with a bowling alley. While everyone thought everything was looking up, it was the start of a remarkable run of

disasters. More fires followed in 1976, 1995, and 2005 wreaking havoc on the pier. In addition, the MV Kingsabbey, a converted waste disposal carrier with a history of accidents crashed into the Southend pier in June 1984, smashing a 70-foot hole in the pier. The damage caused by that crash was not fully repaired until 1989.

disasters. More fires followed in 1976, 1995, and 2005 wreaking havoc on the pier. In addition, the MV Kingsabbey, a converted waste disposal carrier with a history of accidents crashed into the Southend pier in June 1984, smashing a 70-foot hole in the pier. The damage caused by that crash was not fully repaired until 1989.

I like watching football occasionally, but I’m no expert on the game. Over the years, I have learned more about it, but that doesn’t mean that I totally get it. Nevertheless, even I can see when something is completely lopsided, and I can see that something went terribly wrong with a football game that is completely lopsided. Recently, the Denver Broncos played such a game against the Miami Dolphins. Denver lost to Miami, 70 to 20. That is an almost unheard-of loss, and I wondered if the Broncos simply sat on the sidelines and watched the game go down the tubes. I hadn’t watched the game, even though the Broncos are my favorite team. Nevertheless, that game is nowhere near the worst game in history.

I like watching football occasionally, but I’m no expert on the game. Over the years, I have learned more about it, but that doesn’t mean that I totally get it. Nevertheless, even I can see when something is completely lopsided, and I can see that something went terribly wrong with a football game that is completely lopsided. Recently, the Denver Broncos played such a game against the Miami Dolphins. Denver lost to Miami, 70 to 20. That is an almost unheard-of loss, and I wondered if the Broncos simply sat on the sidelines and watched the game go down the tubes. I hadn’t watched the game, even though the Broncos are my favorite team. Nevertheless, that game is nowhere near the worst game in history.

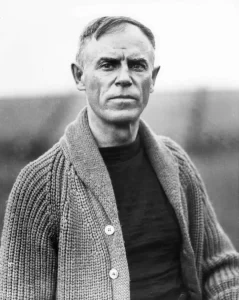

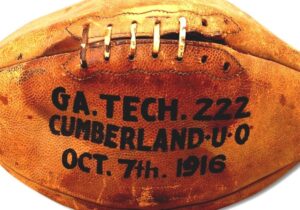

On October 7, 1916, Georgia Tech defeated Cumberland University in a scorchingly lopsided loss of 222 to 0. Of course, these were not professional football players, who would be expected to have better scoring ability, but 222-0 indicates that one team must have stayed in the locker room. The Georgia Tech team was coached by John Heisman, who was later the namesake of college football’s most famous trophy. Georgia Tech took an early 63-0 lead in the first quarter at Grant Field in Atlanta. And they managed to completely shut out every play Cumberland tried to execute. As the Atlanta Constitution reported, “All of Cumberland’s plays were smothered completely.” That was putting it mildly. Ed Haysler Poague, who played for Cumberland, recalled decades later, “I think one of our best plays of the game was when one of our players got the ball on a pitchout and he lost only 10 yards.”

By halftime, the game was “for all intents and purposes” over. Nevertheless, despite a 126-0 halftime lead, Heisman decided to take his team to greatness, so he urged them to keep the pressure on, telling them, “You never know what those Cumberland players have up their sleeve, so in the second half, go out and hit ’em clean and hit ’em hard. Do not let up.” Heisman agreed to shorten the quarters to 12 minutes from 15. There was speculation that he ran up the score because he thought Cumberland, a team out of Lebanon, Tennessee, used professional players to beat Georgia Tech in baseball. Heisman also coached baseball, so that could have been a source of contention, whether it was true or not.

Coach Poage said of his team, “We really didn’t have such a bad team. We were just so ridiculously outclassed that day that it was, well, ridiculous.” The reality is that any team can have a bad day, or even a bad season, but Cumberland just couldn’t catch a break, and after a while, they couldn’t concentrate on what they were doing. It’s common for a coach to tell his team to “keep their head in the game.” That advise doesn’t always do much good, and this time was no exception. By halftime, and trailing 126 to 0, Cumberland couldn’t even see daylight from the hole they were in, much less “keep their head in the game” that they were being slaughtered in.

As for the Georgia Tech fans, well it seems that they thought the Cumberland team might be tough to beat, but before long, they knew better. Coach Poague recalled, “But it didn’t take them long to realize that it wasn’t going to be too difficult. They did a lot of laughing after that.” I’m sure that no one on the Cumberland team  was laughing, during the game or for many months after it. A loss like that is really hard to live down. In reality, Cumberland had discontinued football before the 1916 season, but forgot to tell Coach Heisman, who insisted that the game be played, or face a $3000 forfeit fee, which was a lot of money back then. Cumberland was forced to round up 13 students, many of them fraternity brothers, to go to Atlanta and play. So in their defense, these “football players” were really no such thing, and it was a seriously lopsided game even before it started. Heisman, who had been beaten by Cumberland in a 1915 baseball game, 22 to 0, wanted to have his revenge, so he told his team to keep up the beating, which they did…not that it was really a fair fight.

was laughing, during the game or for many months after it. A loss like that is really hard to live down. In reality, Cumberland had discontinued football before the 1916 season, but forgot to tell Coach Heisman, who insisted that the game be played, or face a $3000 forfeit fee, which was a lot of money back then. Cumberland was forced to round up 13 students, many of them fraternity brothers, to go to Atlanta and play. So in their defense, these “football players” were really no such thing, and it was a seriously lopsided game even before it started. Heisman, who had been beaten by Cumberland in a 1915 baseball game, 22 to 0, wanted to have his revenge, so he told his team to keep up the beating, which they did…not that it was really a fair fight.

What could make a nation go through an earthquake and refuse help from another nation, like the United States? It seems like a strange question, but it is valid. On October 6, 1948, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake leveled Ashgabat, the capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic—now Turkmenistan. The quake killed between 70,000 and 100,000 people. The true number will never be known. In fact, most information of the scope of the disaster remained unknown outside Central Asia until 1973, when archival records were finally unsealed by local officials. So…why seal the records…of an earthquake??

What could make a nation go through an earthquake and refuse help from another nation, like the United States? It seems like a strange question, but it is valid. On October 6, 1948, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake leveled Ashgabat, the capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic—now Turkmenistan. The quake killed between 70,000 and 100,000 people. The true number will never be known. In fact, most information of the scope of the disaster remained unknown outside Central Asia until 1973, when archival records were finally unsealed by local officials. So…why seal the records…of an earthquake??

The town of Ashgabat lies at the foot of the Kopet-Dag Mountain range near the border with Iran. The area is geologically unstable and earthquake prone. That said, why should a large earthquake in an earthquake-prone area need to be hidden? Ashgabat was originally a czarist outpost, founded in 1881. The town grew quickly during World War II, due to evacuees from the war zone. The population grew to an estimated 150,000 people. With a huge influx of people came the need for a lot of new housing, so single-story houses of unreinforced brick and stone, with heavy roofs of packed clay were quickly built, without regard for the need for earthquake proofing. I suppose that was the reason that the authorities didn’t want anyone to come in to help or to know the details of the catastrophe or the number of victims. The schools, hospitals, and other public buildings were built in the same shoddy way. It was wartime, so it may have been that supplies were scarce, or that proper time was not spent on the construction. Of course, less was known about how earthquakes affect buildings too, and even though there were existing seismic standards, they were seldom met. The builders greatly underestimated the earthquake danger, and that was a fact. A 1929 quake had already caused significant property damage, but strangely, the fault zone had been unusually inactive. I suppose this could have been a warning sign. When it is overdue, it may be a sign of an impending catastrophe.

In this case, that was exactly what happened. On October 6, 1948, at 1:17am, with few people awake. Suddenly, they an ominous rumbling from the mountains, followed immediately by violent vertical shaking. It was actually two strong shocks seconds apart, and just as suddenly, Ashgabat was reduced to rubble. There was no escape…there was no time for escape. The buildings were standing one second and collapsed the next. The thing that is the most shocking was that many of the survivors, who had been conditioned by propaganda in the acute early phase of the Cold War, thought that the city had been hit by an American atomic bomb. And the government did nothing to correct their misguided thinking. So, the country did not seek help from the United States.

As suddenly as it had occurred, the quake severed all communications with the outside world. There were no emergency centers, because hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies lay in ruins. The few remaining uninjured rescue workers, members of the city’s emergency services struggled in the darkness to help the injured. Doctors, many of whom had served in the war, pulled equipment from the ruins to set up an emergency station in Karl Marx Square. Finally, by the afternoon, reinforcements and supplies began to arrive from Tashkent and Baku. Nevertheless, the number of casualties, and the inherent difficulty of evacuating gravely wounded people, meant that help came too late for many. It was estimated that half of an estimated thirty thousand people who  had life-threatening injuries died from lack of early treatment…many people died before they could even be pulled from the rubble.

had life-threatening injuries died from lack of early treatment…many people died before they could even be pulled from the rubble.

While the city workers immediately ran to the damaged central headquarters of the Communist Party, where they were told by the party’s first secretary, S Batirova to take an undamaged automobile and head northward to a functioning telephone line, and soldiers stationed at the airport used an aircraft radio to contact Baku and Sverdlovsk, it was still many hours before any details reached areas from which aid could be dispatched.Unfortunately, that wasn’t much help either, because the railway station was in ruins, tracks were blocked, the airport control tower was destroyed, and the airport and roads could not handle heavy traffic. It would take hours and even days, to get the much-needed rescue support the city needed.

Of course, because of the misguided concept that the Americans were somehow involved, the precise death toll will never be known for sure. Estimates range from a shockingly low number of 400, suggested by Nature magazine in 1948, to a more likely number of 110,000. The dead were buried in mass graves. They were not counted or identified, adding to the confusion. There were roughly 50,000 survivors in a city that had previously had a population of approximately 150,000. That suggests that a death toll of 80,000 to 100,000, or about two-thirds of the population is a more accurate number.

The death toll was enormous, and that could have also accounted for the lack of emergency workers. It’s highly likely that many of them were among the dead or injured…not to mention the fact that there may have been a gross shortage of qualified rescue workers in the poorest part of a country, which was just still recovering from long years of war, but the poor response from the rest of the Soviet Union became more and more unconscionable. On October 7, Pravda printed a brief article stating only that “geologists at the Russian Academy of Sciences had detected a strong earthquake.” The article also reported that there were supply shipments and of the evacuation of the wounded, but no mention of the scope of devastation or the number of casualties. Of course, the international press used Pravda’s limited and incorrect reportage about the quake as the source for their own news reports.

To make matters worse, a conspiracy of silence followed the destruction of Ashgabat. Most history books and almanacs of natural disasters actually omit the quake entirely!! In the typical Soviet propaganda style of the 1950’s, they actually praised the severely lacking reconstruction efforts that completely ignored seismological standards. One Soviet journalist who visited the city in 1953, later described being “forbidden to photograph the omnipresent ruins or to report a march of weeping survivors to the mass graves on the outskirts of the city.” Little was known about the devastating earthquake until 1973. Only on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the event, did officials in Turkmenistan begin to open sealed archives and acknowledge the terrible calamity. Why was this? It was largely because of the Cold War, when both sides were eager not to expose their strategic vulnerabilities. That still doesn’t make sense, however, because the destruction of Ashgabat neither compromised the Soviet Union’s defense system nor revealed grave internal weaknesses. The forced silence did nothing to improve domestic morale in Russia, and it created widespread resentment in Central Asia.  Internationally the Soviet Union could have gained propaganda points by publicizing the disaster and then criticizing the lack of response from the West, but for some reason, they didn’t so that either. Of course, the people in the Soviet Union lived in fear of Joseph Stalins sweeping purges and force silence and timidity. They didn’t dare speak of any kind of vulnerability. Until Stalin’s death in 1953, even referencing the event was considered a dangerous move. Financial aid was still desperately needed decades after the disaster, yet it still didn’t really come. Silence translated into slow reconstruction. Substantial portions of the city remain in ruins, and a significant portion of the population still lives in temporary, or inadequate and unsafe, dwellings to this day.

Internationally the Soviet Union could have gained propaganda points by publicizing the disaster and then criticizing the lack of response from the West, but for some reason, they didn’t so that either. Of course, the people in the Soviet Union lived in fear of Joseph Stalins sweeping purges and force silence and timidity. They didn’t dare speak of any kind of vulnerability. Until Stalin’s death in 1953, even referencing the event was considered a dangerous move. Financial aid was still desperately needed decades after the disaster, yet it still didn’t really come. Silence translated into slow reconstruction. Substantial portions of the city remain in ruins, and a significant portion of the population still lives in temporary, or inadequate and unsafe, dwellings to this day.

The loss of a loved one is one of the hardest of life events, and when it is a child, be it a young child or an adult child, it is even worse. For my uncle, Lester “Jim” Wolfe and my aunt, Ruth Wolfe, the loss of their adult son, Larry Wolfe in an explosion on May 16, 1976, was a devastation. They, like any parent, had a really hard time coping with the loss. They were living in Vallejo, California at the time, but after their loss, they could no longer stay there. They had to get out of California. It was then that a move to Washington state seemed their best option. I don’t know if Washington had been on their radar prior to Larry’s passing at 26 years old, or not, but they moved the entire family to the mountains outside Newport, in eastern Washington state. They purchased basically the entire mountain top, and built three cabins, where they would live out their lives.

The loss of a loved one is one of the hardest of life events, and when it is a child, be it a young child or an adult child, it is even worse. For my uncle, Lester “Jim” Wolfe and my aunt, Ruth Wolfe, the loss of their adult son, Larry Wolfe in an explosion on May 16, 1976, was a devastation. They, like any parent, had a really hard time coping with the loss. They were living in Vallejo, California at the time, but after their loss, they could no longer stay there. They had to get out of California. It was then that a move to Washington state seemed their best option. I don’t know if Washington had been on their radar prior to Larry’s passing at 26 years old, or not, but they moved the entire family to the mountains outside Newport, in eastern Washington state. They purchased basically the entire mountain top, and built three cabins, where they would live out their lives.

They lived a good life on the mountain top. They were completely off the grid, something that is common these  days, but not so much back then. Nevertheless, they craved total isolation, and the mountain top provided just that. Still, while they wanted to be left alone, they still enjoyed traveling, and they came out to see our family several times after that. Aunt Ruth was my dad, Allen Spencer’s sister, after all. Uncle Jim lost Aunt Ruth to cancer, on May 11, 1992, when she was just 66 years old. I’m sure he quickly learned to dread the coming of May. After that, we lost touch with them unto shortly before Uncle Jim passed away on January 30, 2013. We had reconnected with his daughter, my cousin Shirley Cameron in 2011, but by that time Uncle Jim was already in a nursing home with Dementia. We were always sad about that, but for the most part Uncle Jim was happy. His favorite things to do were strolling down the halls in his wheelchair singing and flirting with the nurses that worked there. They all loved him and thought his flirting was cute, and knowing my uncle like I did, I’m sure he was also a great jokester. He always had been, so playing pranks on the nurses came naturally. He once tried hiding in the nurses’ station but got caught. I’m not sure if his plan was to scare them or to catch one around the waist when she wasn’t looking. I wouldn’t put either choice past him. Uncle Jim was always a lighthearted person and great fun to be around. He loved to take his family camping, and maybe that was a big part of the reason the family moved to the mountains of Washington in the first place.

days, but not so much back then. Nevertheless, they craved total isolation, and the mountain top provided just that. Still, while they wanted to be left alone, they still enjoyed traveling, and they came out to see our family several times after that. Aunt Ruth was my dad, Allen Spencer’s sister, after all. Uncle Jim lost Aunt Ruth to cancer, on May 11, 1992, when she was just 66 years old. I’m sure he quickly learned to dread the coming of May. After that, we lost touch with them unto shortly before Uncle Jim passed away on January 30, 2013. We had reconnected with his daughter, my cousin Shirley Cameron in 2011, but by that time Uncle Jim was already in a nursing home with Dementia. We were always sad about that, but for the most part Uncle Jim was happy. His favorite things to do were strolling down the halls in his wheelchair singing and flirting with the nurses that worked there. They all loved him and thought his flirting was cute, and knowing my uncle like I did, I’m sure he was also a great jokester. He always had been, so playing pranks on the nurses came naturally. He once tried hiding in the nurses’ station but got caught. I’m not sure if his plan was to scare them or to catch one around the waist when she wasn’t looking. I wouldn’t put either choice past him. Uncle Jim was always a lighthearted person and great fun to be around. He loved to take his family camping, and maybe that was a big part of the reason the family moved to the mountains of Washington in the first place.

It was with heavy hearts that we attended the funeral of our uncle. My mom, Collene Spencer, sister, Cheryl

Masterson, and I all made the trip to Washington. It was a bittersweet trip. We were happy to see their family again. We had not seen my cousin, Terry Wolfe, Shirley’s brother in many years either, although we had texted back and forth a little. We just wished that the reason for the trip had not been my Uncle Jim’s funeral. While it would have been hard, we would much rather have been able to visit him at the nursing home just once before his passing. Today would have been Uncle Jim’s 102nd birthday had he still been with us. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Jim. We love and miss you very much.

Masterson, and I all made the trip to Washington. It was a bittersweet trip. We were happy to see their family again. We had not seen my cousin, Terry Wolfe, Shirley’s brother in many years either, although we had texted back and forth a little. We just wished that the reason for the trip had not been my Uncle Jim’s funeral. While it would have been hard, we would much rather have been able to visit him at the nursing home just once before his passing. Today would have been Uncle Jim’s 102nd birthday had he still been with us. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Jim. We love and miss you very much.

I love watching the pigeons that fly around at one end of the walking path I use regularly. They are wild of course, but maybe at one time they were owned…or maybe their parents were. Now, they are free to soar around in beautiful formations, as they enjoy the freedom of being carefree and, well just being birds. Not all pigeons are free, however, and some even perform a very important service…some to their country. Pigeons have actually been used in wars to carry messages to different battalions, sadly because they were expendable, where the men were not.

I love watching the pigeons that fly around at one end of the walking path I use regularly. They are wild of course, but maybe at one time they were owned…or maybe their parents were. Now, they are free to soar around in beautiful formations, as they enjoy the freedom of being carefree and, well just being birds. Not all pigeons are free, however, and some even perform a very important service…some to their country. Pigeons have actually been used in wars to carry messages to different battalions, sadly because they were expendable, where the men were not.

One famous pigeon known as “President Wilson,” was hatched in France. “President Wilson” (this special pigeon) assisted both the American tank corps and US infantry men in their fight against Germany. It was in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, that “President Wilson” made his most famous flight. He was assisting the 78th Infantry near Grandpre. The battle had been a vicious one, and while engaging the enemy on the morning of October 5, 1918, President Wilson’s unit released him to request artillery support. No flight through a battleground was easy, but this one was especially dangerous. A bird can’t really fly without being seen, and the Germans knew to watch for pigeons. The German soldiers opened fire on him, peppering him with bullets. “President Wilson” sustained numerous injuries, nevertheless, he was able to make his flight back to headquarters in record setting time…under 25 minutes. “President Wilson” survived his wounds, after which he was retired and sent to the US Army Signal Corps Breeding and Training Center at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, where he would live another eleven years. After his death, Wilson was taxidermized and presented to the Smithsonian Institution. He was transferred to the custody of the US Army in 2008. “President Wilson” is now located in the prestigious halls of the US military’s headquarters in Arlington, Virginia. He serves as a reminder that these simple birds…often considered a nuisance by the general public…were once war heroes.

Another famous pigeon was known as Cher Ami, who also gained fame during World War I. Cher Ami’s moment of heroism came during the actions of the so-called “Lost Battalion.” With the 77th Division finding themselves  surrounded by the German army, besieging them for five days, Cher Ami was the third pigeon sent out to tell division headquarters that the men were surrounded and were taking fire, both enemy and friendly!! Cher Ami was hit almost as quickly as he rose. He was shot down but managed to take flight again. He arrived back at his loft at division headquarters 25 miles to the rear in just 25 minutes, helping to save the lives of the 194 survivors. He had been shot through the breast, blinded in one eye, and had a leg hanging only by a tendon. Cher Ami was the last pigeon available. Had he not made it, the men would have been on their own. Cher Ami was stuffed and mounted after his death and is now in the Smithsonian Museum of American History.

surrounded by the German army, besieging them for five days, Cher Ami was the third pigeon sent out to tell division headquarters that the men were surrounded and were taking fire, both enemy and friendly!! Cher Ami was hit almost as quickly as he rose. He was shot down but managed to take flight again. He arrived back at his loft at division headquarters 25 miles to the rear in just 25 minutes, helping to save the lives of the 194 survivors. He had been shot through the breast, blinded in one eye, and had a leg hanging only by a tendon. Cher Ami was the last pigeon available. Had he not made it, the men would have been on their own. Cher Ami was stuffed and mounted after his death and is now in the Smithsonian Museum of American History.

Looking back on World War I, and the many lives lost, we also need to remember that without war heroes like “President Wilson” and Cher Ami the losses would have been far greater. Many pigeons lost their lives in these efforts, but they were heroes for the sacrifices they made. I’m sure the soldiers knew that well.

As long as there have been vehicles, there have been people who felt the need to race them. Enter Sidecar Racing. Like all forms of racing, Sidecar Racing began with started with vehicles built for the street. They were a simple motorcycle with a simple sidecar attachment. Over the years, however, the sidecars have evolved to increase speed and safety.

As long as there have been vehicles, there have been people who felt the need to race them. Enter Sidecar Racing. Like all forms of racing, Sidecar Racing began with started with vehicles built for the street. They were a simple motorcycle with a simple sidecar attachment. Over the years, however, the sidecars have evolved to increase speed and safety.

`

The early modifications were to lower the center of gravity by laying the driver forward over the engine. This modification reminds me of the Ninja motorcycle, otherwise known as the crotch rocket. It inspires speed in the vehicle. The sidecar itself was also changed from a mere basket to a platform, so that the passenger or monkey, could be mobile. Having a mobile passenger meant a moveable mass to help keep the tires on the ground at higher speeds. The passenger could lean this way and that to help stabilize the motorcycle and sidecar. As with any vehicle, the basic motorcycle components were used to build the racer…engine, steering, and larger diameter treaded tires. The racer was void of anything that could get in the way of aerodynamics. All that was there were fenders and whatever the driver and passenger could provide. Oddly, this type of sidecar, original around 1949, is still raced today in vintage classes, and most are home built.

Nevertheless, the vintage class has given way to the modern class, and after years of modifications and updates and the modern sidecar has emerged. Even today, some of the modern sidecars are home-built, but there are also companies who are dedicated to building sidecars. Whereas the home-built sidecars tend to be  made of steel tubing and are less refined, the specialized companies use aluminum, carbon fiber, or other types of stronger, lighter material, designed to make the vehicle even faster. These specialized shops are also able to build a vehicle with a better suspension and better handling, as well as single swing arms for ease of wheel change. The modern sidecars use slick tires, as opposed to the larger diameter treaded tires. Race cars made the slick tires “famous” for their ability to build speed before takeoff. They also have molded aerodynamic bodies, probably much better than the home-built models, at least as far as speed is concerned.

made of steel tubing and are less refined, the specialized companies use aluminum, carbon fiber, or other types of stronger, lighter material, designed to make the vehicle even faster. These specialized shops are also able to build a vehicle with a better suspension and better handling, as well as single swing arms for ease of wheel change. The modern sidecars use slick tires, as opposed to the larger diameter treaded tires. Race cars made the slick tires “famous” for their ability to build speed before takeoff. They also have molded aerodynamic bodies, probably much better than the home-built models, at least as far as speed is concerned.

These days, there are three types of modern sidecars. Known as F1 (Formula 1), F2 (Formula 2), and F3 (Formula 3), with the F2 and F3 sidecars having the motors positioned under the drivers. Oddly, for full out speed, the best choice is the F1 model sidecar. I guess that placing the driver on top of the engine wasn’t the best modification for speed. The F1 models are sometimes referred to as long bikes. The motor on the F1 is behind the driver. The maximum engine displacement in this category is 1000cc 4 stroke. For the F2, the maximum engine displacement is 600cc 4 stroke or 500 cc 2 stroke. Engines are pre-1996 for F3. The F2 and F3 sidecars have a shorter wheelbase than the F1. This gives them better handling on short tracks, so  apparently the racer needs to know what model will fill the need for the track being raced. Whichever class the racer choses, the sidecar wheel will not have any suspension. The engines can be carbureted, or fuel injected. One hard and fast rule is that they must also be chain or belt drive, because shaft drive engines are allowed. Other than these many changes, the basic design is the same as the vintage sidecar racers. Obviously, if the sidecar were placed anywhere else, it would not be a sidecar. The sidecar racers usually run between $6,000 to $20,000 and will last for several years…probably a bargain considering the amount of money that goes into most race vehicles.

apparently the racer needs to know what model will fill the need for the track being raced. Whichever class the racer choses, the sidecar wheel will not have any suspension. The engines can be carbureted, or fuel injected. One hard and fast rule is that they must also be chain or belt drive, because shaft drive engines are allowed. Other than these many changes, the basic design is the same as the vintage sidecar racers. Obviously, if the sidecar were placed anywhere else, it would not be a sidecar. The sidecar racers usually run between $6,000 to $20,000 and will last for several years…probably a bargain considering the amount of money that goes into most race vehicles.

FIM (International Motorcycling Federation) Sidecar World Championship is the international sidecar racing championship. It is the only remaining original FIM road racing championship class that started in 1949.

Many people have heard about the 1970 plane crash that killed the Marshall University football team, but what many people may not know is that the Marshall University crash was not the only crash that year, or even the first crash involving a football team. The first one involved the Wichita Stake Shockers football team. On Friday, October 2, 1970, at 1:14pm, in clear and calm weather, with amazing visibility, the Wichita State chartered 4-0-4 airliner crashed into a mountain peak just eight miles west of Silver Plume in Colorado. The plane, operated by Golden Eagle Aviation, the twin-engined propliner carried 37 passengers and a crew of three. Of those onboard, 29 were killed at the scene and two later died of their injuries at the hospital.

Many people have heard about the 1970 plane crash that killed the Marshall University football team, but what many people may not know is that the Marshall University crash was not the only crash that year, or even the first crash involving a football team. The first one involved the Wichita Stake Shockers football team. On Friday, October 2, 1970, at 1:14pm, in clear and calm weather, with amazing visibility, the Wichita State chartered 4-0-4 airliner crashed into a mountain peak just eight miles west of Silver Plume in Colorado. The plane, operated by Golden Eagle Aviation, the twin-engined propliner carried 37 passengers and a crew of three. Of those onboard, 29 were killed at the scene and two later died of their injuries at the hospital.

The plane was one of two 4-0-4 airliners flying the team to Logan, Utah. Three months earlier Wichita State had contracted Golden Eagle Aviation to supply a Douglas DC-6B, to fly the team to away games for the 1970 season. The four-engined DC-6 was a large, powerful aircraft that could accommodate the entire team in one plane. At the time of the contract, Golden Eagle Aviation did not own the DC-6. Nevertheless, they had made an arrangement with the Jack Richards Aircraft Company to use theirs. Unfortunately, after the agreements were made, the Jack Richards Aircraft Company DC-6 was damaged in a windstorm, so at the last minute it was unavailable for use. The two Martin 4-0-4s, hadn’t flown since 1967, so thy were quickly re-certified for flight. While it might seem like that could have been the cause of the crash, it was not. On October 2, 1970, the two 4-0-4s were ferried from the Jack Richards Aircraft Company facilities in Oklahoma City to Wichita, instead of the expected DC-6. The 4-0-4s were smaller planes, and so the team had to be split into two groups. Upon arrival in Wichita, the two aircraft were loaded with luggage and the passengers were boarded. The planes then headed west to a refueling stopover in Denver at Stapleton Airport. From Denver, they would continue to Logan Airport in northern Utah. The two planes were dubbed “Gold” and “Black” after the school colors. “Gold” was the aircraft that later crashed. It carried the starting players, head coach, and athletic director, as well as their wives, other administrators, boosters, and family. The “Black” plane transported the reserve players, assistant coaches, and other support personnel, and it took the normal route from Denver to Logan, going by way of the original flight plan and took a more northerly route, heading north from Denver to southern Wyoming then west, using a designated airway. This was less scenic, but this route allowed more time to gain altitude for the climb over the Rocky Mountains. The “Black” plane arrived safely in Utah.

The plane dubbed “Gold” took a more scenic route. The President of Golden Eagle Aviation, 37-year-old Ronald G Skipper, was the pilot flying the “Gold” plane. Normally, he would have been the pilot, but he was not rated for the 4-0-4, so he was acting as the first officer. During the flight to Denver, he visited passengers in the cabin, telling them of his plans to take a more scenic route, near Loveland Ski Area and Mount Sniktau, the proposed alpine skiing venues for the 1976 Winter Olympics, recently awarded to Denver in May. The captain of the “Gold” aircraft was 27-year-old Danny E Crocker, who occupied the right seat. While the aircraft was being refueled and serviced in Denver, First Officer Skipper purchased aeronautical sectional charts for the contemplated scenic route. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation report stated the First Officer testified that he intended to use the charts to help point out landmarks and objects of interest to the passengers. Unfortunately, this last-minute decision didn’t allow time to review the maps to make sure that they were traveling on a safe route, and that they were high enough to make it over the mountains.

Shortly before the crash, several witnesses described seeing an aircraft flying unusually low towards the

Continental Divide, which is, of course, quite high in altitude. Some witnesses who were located on higher mountainside locations, such as Loveland Pass at 11,990 feet, reported seeing it flying below them…into the mountains!! It is difficult for me to understand, how the pilots could no have seen this as a serious problem. Crash survivor Rick Stephens was a senior guard and stated in 2013, “…as we flew along over I-70, that there were old mines and old vehicles above us. I noticed we were quite a bit below the top of the mountains. I got up to go to the cockpit, which wasn’t unusual to do, and I could tell we were in trouble, looking out the window and seeing nothing but green in front of us.”

Continental Divide, which is, of course, quite high in altitude. Some witnesses who were located on higher mountainside locations, such as Loveland Pass at 11,990 feet, reported seeing it flying below them…into the mountains!! It is difficult for me to understand, how the pilots could no have seen this as a serious problem. Crash survivor Rick Stephens was a senior guard and stated in 2013, “…as we flew along over I-70, that there were old mines and old vehicles above us. I noticed we were quite a bit below the top of the mountains. I got up to go to the cockpit, which wasn’t unusual to do, and I could tell we were in trouble, looking out the window and seeing nothing but green in front of us.”

The other problem the plane had was that it was overloaded. Sadly, no one double checked the weight to make sure they were within safe limits. As the plane neared Loveland Pass, it flew up Clear Creek Valley, where it became trapped in a box canyon and was unable to climb above the mountain ridges surrounding it on three sides. It was also unable to complete a reversal turn away from the sharply rising terrain. At 1:14pm MDT, the “Gold” plane struck trees on the east slope of Mount Trelease, 1,600 feet below its summit, and crashed. The NTSB report stated that quite likely many of the passengers on board actually survived the initial impact. This was based on the testimony of survivors and rescuers. The load of fuel on board did not explode immediately. This allowed some of the survivors to escape the wreckage. Then, the passenger cabin exploded and trapped the people who were still alive. They had no way of escape. Of the 40 people on board, the death count at the scene was 29, which included 27 passengers, the captain, and flight attendant. One of the deceased passengers was an off-duty flight attendant who was assisting. Two of the initial 11 survivors later died of their injuries to bring the total dead to 31, 14 of whom were Wichita State football players. First to arrive at the crash scene were construction workers from the nearby Eisenhower Tunnel project and motorists on U.S. 6 (I-70). The first officer (company president) survived.

The National Transportation Safety Board report states that the weather did not play a role in the accident, but rather lists the probable cause to be that the pilot made improper decisions in-flight or in planning. The overloading probably played a part too, in that they couldn’t climb as fast as if they had not been overloaded. The report said that the cause was, “the intentional operation of the aircraft over a mountain valley route at an altitude from which the aircraft could neither climb over the obstructing terrain ahead, nor execute a successful course reversal, while other significant factors were the overloaded condition of the aircraft, the virtual absence of flight planning for the chosen route of flight from Denver to Logan, as well as a lack of understanding on the part of the crew of the performance capabilities and limitations of the aircraft, and the lack of operational management to monitor and appropriately control the actions of the flight crew.” It was a recipe for disaster. What I don’t understand is how the plane could have crashed less than a mile from an interstate highway that was straight and level in that area…the perfect place for an emergency landing. Why didn’t they use it?

Of course, the game was canceled, as were classes at Wichita State University. Utah State University’s football team held a memorial in the stadium where the game was to have been played…placing a wreath on the 50-yard line. Wichita State University officials and family members of the survivors were flown to Denver on an aircraft made available by Robert Docking, the Governor of Kansas. A memorial service was held on Monday, October 5th at Cessna Stadium in Wichita. The remaining members of the Wichita State team, with the NCAA and Missouri Valley Conference allowing freshman players to fill out the squad, decided to continue the 1970 season in honor of those lost. It was later designated the “Second Season.” Wichita State and Utah State had played in five of the previous six seasons, but never met again in football. Unable to fully recover from its loss,  Wichita State discontinued varsity football after the 1986 season. Roadside memorial in Colorado on Interstate 70, milepost 217 Wichita State University built a memorial for those who died from the crash called Memorial ’70. Every year on October 2 at 9 a.m., a wreath is placed at this memorial. A roadside memorial plaque listing the names of the victims is located near the Colorado crash site, adjacent to westbound Interstate 70, at Dry Gulch at milepost 217, about two miles east of the Eisenhower Tunnel. A trail to the wreck site via Dry Gulch is 0.4 miles past the memorial off exit 216.

Wichita State discontinued varsity football after the 1986 season. Roadside memorial in Colorado on Interstate 70, milepost 217 Wichita State University built a memorial for those who died from the crash called Memorial ’70. Every year on October 2 at 9 a.m., a wreath is placed at this memorial. A roadside memorial plaque listing the names of the victims is located near the Colorado crash site, adjacent to westbound Interstate 70, at Dry Gulch at milepost 217, about two miles east of the Eisenhower Tunnel. A trail to the wreck site via Dry Gulch is 0.4 miles past the memorial off exit 216.

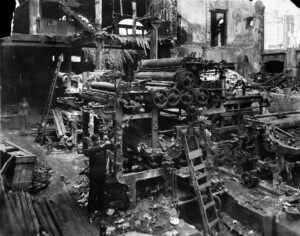

These days, terrorist attacks are…if not common, expected to happen at some point. It’s the crazy world we now live in, but in 1910, it wasn’t quite so common. Nevertheless, on October 1, 1910, there was a massive explosion that destroyed the Los Angeles Times building in the LA’s downtown area. The bombing killed 21 people and injuring many more. Harrison Otis, who was the Los Angeles Times publisher and a bitter opponent of unions, believed that the bomb was directed at him. So, he hired William J Burns, the nation’s top private detective to find out who the culprits were. Otis, in addition to printing numerous editorials against unions, was the leader of the Merchants and Manufacturing Association, which was a powerful group of business owners, all of whom had extensive political connections.

These days, terrorist attacks are…if not common, expected to happen at some point. It’s the crazy world we now live in, but in 1910, it wasn’t quite so common. Nevertheless, on October 1, 1910, there was a massive explosion that destroyed the Los Angeles Times building in the LA’s downtown area. The bombing killed 21 people and injuring many more. Harrison Otis, who was the Los Angeles Times publisher and a bitter opponent of unions, believed that the bomb was directed at him. So, he hired William J Burns, the nation’s top private detective to find out who the culprits were. Otis, in addition to printing numerous editorials against unions, was the leader of the Merchants and Manufacturing Association, which was a powerful group of business owners, all of whom had extensive political connections.

The investigation led Burns to the Bridge and Structural Iron Workers Union and their treasurer, John J McNamara. Burns personally arrested McNamara and his brother in Indiana in April 1911, after Burns got a confession out of Ortie McManigal. It seems that McManigal had allegedly been the intermediary between  McNamara and two bomb experts. Burns had no legal authority to arrest anyone, but he did so, and managed to get the brothers to California, where they were scheduled to be prosecuted.

McNamara and two bomb experts. Burns had no legal authority to arrest anyone, but he did so, and managed to get the brothers to California, where they were scheduled to be prosecuted.

As is typical, and even expected, the Union members and left-wing supporters all rallied around the McNamara brothers. They raised a large defense fund, and union representatives pleaded with Clarence Darrow to take the case. Darrow was well known as the best defense attorney in America. He had already managed to get “Big Bill” Haywood, the union leader of the Industrial Workers of the World, off on murder charges in Idaho a few years earlier. After being offered $50,000, Darrow reluctantly took the case. Public opinion supported the McNamara brothers, but the investigation Darrow performed was quickly turning up evidence to prove that the brothers were actually guilty. To make matters worse, members of the defense team tried to bribe the jury, just to keep up with the prosecution’s own bribery tactics. In the end, Darrow worked out a deal with Otis and the prosecutors that the brothers would plead guilty to escape the death penalty, which they did. It was the best he could do for them.

Still, this plan was not acceptable to either side, and Darrow got caught in the middle. Darrow was soon  charged with bribery, and Otis arranged for Darrow’s prosecution. The union immediately deserted the great defense lawyer…not only did they refuse to pay his fee for the McNamara case, but they also refused to assist in his defense. Thankfully for Darrow, Earl Rogers, who was a notorious drunk, but also a brash, formidable, and effective Los Angeles attorney, took Darrow’s case. True to his reputation, Rogers managed to secure a mistrial for Darrow. Later, Darrow was acquitted after a second trial. Undaunted, Darrow went on to try even more distinguished cases, including the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes evolution trial. Still, I doubt if any trial stood out in his memory quite as much as the trial that almost cost him his freedom.

charged with bribery, and Otis arranged for Darrow’s prosecution. The union immediately deserted the great defense lawyer…not only did they refuse to pay his fee for the McNamara case, but they also refused to assist in his defense. Thankfully for Darrow, Earl Rogers, who was a notorious drunk, but also a brash, formidable, and effective Los Angeles attorney, took Darrow’s case. True to his reputation, Rogers managed to secure a mistrial for Darrow. Later, Darrow was acquitted after a second trial. Undaunted, Darrow went on to try even more distinguished cases, including the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes evolution trial. Still, I doubt if any trial stood out in his memory quite as much as the trial that almost cost him his freedom.

Trainwrecks can obviously happen at any time, but I think the worst time would be in the middle of the night, when the people onboard…other than the crew…are sleeping, or at the very least, dozing. There is nothing worse than being awakened to impending disaster. On September 30, 1945, a train was on its way from Perth to London Euston. The train was the 15-coach overnight Perth to London Euston express hauled by LMS Royal Scot Class 4-6-0 No 6157 The Royal Artilleryman. Part of the journey was to include a diversion, due to engineering work being done on the Watford tunnel. The train was scheduled to switch from the fast to the slow lines at Bourne End, near Hemel Hempstead. For reason unknown, the engineer failed to slow the train down in response to cautionary signals on the approach to the diversion. As a result, the train entered a 15-mile-per-hour turnout at nearly 60 miles per hour.

Trainwrecks can obviously happen at any time, but I think the worst time would be in the middle of the night, when the people onboard…other than the crew…are sleeping, or at the very least, dozing. There is nothing worse than being awakened to impending disaster. On September 30, 1945, a train was on its way from Perth to London Euston. The train was the 15-coach overnight Perth to London Euston express hauled by LMS Royal Scot Class 4-6-0 No 6157 The Royal Artilleryman. Part of the journey was to include a diversion, due to engineering work being done on the Watford tunnel. The train was scheduled to switch from the fast to the slow lines at Bourne End, near Hemel Hempstead. For reason unknown, the engineer failed to slow the train down in response to cautionary signals on the approach to the diversion. As a result, the train entered a 15-mile-per-hour turnout at nearly 60 miles per hour.

They were going far too fast, and the train couldn’t maintain its position on the tracks. The engine and the first six cars overturned and fell down an embankment into a field. When the derailment was over, only the last  three cars remained on the rails, 43 people were dead, and 65 people were injured. The investigation determined that the cause was driver error, possibly compounded by ambiguous signaling regulations. The fact that the engineer was very experienced with a reputation for being conscientious and had read the notice about the diversion before leaving Crewe, makes the accident that much more odd. It is thought that he may not have appreciated its significance of the diversion. He had worked 26 days consecutively due to staff shortages following the war, so it was possible that he had either momentarily dozed off or that fatigue caused him to momentarily go into “autopilot” mode. Unfortunately, this particular line had not yet been fitted with the Automatic Warning System, which probably could have prevented the accident.

three cars remained on the rails, 43 people were dead, and 65 people were injured. The investigation determined that the cause was driver error, possibly compounded by ambiguous signaling regulations. The fact that the engineer was very experienced with a reputation for being conscientious and had read the notice about the diversion before leaving Crewe, makes the accident that much more odd. It is thought that he may not have appreciated its significance of the diversion. He had worked 26 days consecutively due to staff shortages following the war, so it was possible that he had either momentarily dozed off or that fatigue caused him to momentarily go into “autopilot” mode. Unfortunately, this particular line had not yet been fitted with the Automatic Warning System, which probably could have prevented the accident.

As a train comes up to turns or track changes, the railroad provides advance warning of the turnout by “a color light distant signal showing double yellow, an outer home signal showing green, and two ‘splitting’ semaphore inner homes side by side showing which route was set. The double yellow aspect could have an important extra meaning under Rule 35b(ii), “In some cases, color light signals will exhibit two yellow lights. This indication means – Pass next signal at restricted speed, and if applicable to a junction may denote that the points are set for a diverging route over which the speed restriction shown in the appendix applies.” Because this arrangement is ambiguous, the inspector pointed out that it evidently did not alert the engineer to the  approaching low speed turnout. It was unclear why he failed to notice the diverging route indication of the splitting inner homes. It’s possible that the low sun shining directly in his face would have made observation tiring, but the signals were still clearly visible.

approaching low speed turnout. It was unclear why he failed to notice the diverging route indication of the splitting inner homes. It’s possible that the low sun shining directly in his face would have made observation tiring, but the signals were still clearly visible.

The accident was first reported by a pilot who had just taken off from Bovingdon Aerodrome. As he took off, he could see the accident, so he immediately notified the railway authorities via the Bovingdon Control tower. Airfield staff also helped significantly with assistance after the crash. With the death toll at 43, this became Britain’s joint seventh worst rail disaster in terms of death toll.