Caryn’s Thoughts

Sellafield, which was formerly known as Windscale Works, was an important multi-functional nuclear site located near Seascale on the coast of Cumbria, England. As of August 2022, its primary activities are the processing and storage of nuclear waste, along with decommissioning. Historically, the facility produced nuclear power from 1956 to 2003 and reprocessed nuclear fuel from 1952 to 2022. Originally built as a Royal Ordnance Factory in 1942, the site was briefly owned by Courtaulds for rayon production in the post-World War II years. Then in 1947, the Ministry of Supply reacquired it for plutonium production, leading to the construction of the Windscale Piles and the First-Generation Reprocessing Plant, and its renaming to “Windscale Works.” Significant developments followed, including the construction of Calder Hall, the world’s first commercial nuclear power station to supply electricity to a public grid, the Magnox fuel reprocessing plant, the prototype Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor (AGR), and the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (THORP). Decommissioning has been concentrated on the Windscale Piles, Calder Hall, and various historic reprocessing and waste storage facilities.

Sellafield, which was formerly known as Windscale Works, was an important multi-functional nuclear site located near Seascale on the coast of Cumbria, England. As of August 2022, its primary activities are the processing and storage of nuclear waste, along with decommissioning. Historically, the facility produced nuclear power from 1956 to 2003 and reprocessed nuclear fuel from 1952 to 2022. Originally built as a Royal Ordnance Factory in 1942, the site was briefly owned by Courtaulds for rayon production in the post-World War II years. Then in 1947, the Ministry of Supply reacquired it for plutonium production, leading to the construction of the Windscale Piles and the First-Generation Reprocessing Plant, and its renaming to “Windscale Works.” Significant developments followed, including the construction of Calder Hall, the world’s first commercial nuclear power station to supply electricity to a public grid, the Magnox fuel reprocessing plant, the prototype Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor (AGR), and the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (THORP). Decommissioning has been concentrated on the Windscale Piles, Calder Hall, and various historic reprocessing and waste storage facilities.

During its “Windscale Works” years, a severe fire broke out in the core of a nuclear reactor on October 10, 1957. As a result, significant radioactive material was released into the environment on October 10-11, 1957. Windscale Works was under the operation of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) at the time. On the 15th of October, the UKAEA Chairman announced the formation of an Inquiry Committee, chaired by Sir William Penney, to investigate the incident. The Committee convened at  Windscale Works from October 17–25th. They interviewed 37 individuals and reviewed 73 technical exhibits. They submitted their findings to the UKAEA Chairman on 26th October. These findings underpinned a UK Government White Paper (Command Paper 302), published on November 8, 1957. Oddly or perhaps criminally, the Penney Report itself remained unpublished until it was made available at The National Archives, Kew, in January 1988, basically covering up the event for decades. This event transpired when uranium metal fuel caught fire within Windscale Pile No. 1. The fire led to the release of radioactive contamination into the environment, which is estimated to have eventually caused approximately 240 cancer cases, with fatalities between 100 to 240. The incident received a level 5, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The maximum rating is 7.

Windscale Works from October 17–25th. They interviewed 37 individuals and reviewed 73 technical exhibits. They submitted their findings to the UKAEA Chairman on 26th October. These findings underpinned a UK Government White Paper (Command Paper 302), published on November 8, 1957. Oddly or perhaps criminally, the Penney Report itself remained unpublished until it was made available at The National Archives, Kew, in January 1988, basically covering up the event for decades. This event transpired when uranium metal fuel caught fire within Windscale Pile No. 1. The fire led to the release of radioactive contamination into the environment, which is estimated to have eventually caused approximately 240 cancer cases, with fatalities between 100 to 240. The incident received a level 5, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The maximum rating is 7.

Now called Sellafield, the licensed premises span 650 acres, housing over 200 nuclear facilities and more than 1,000 buildings. It stands as the largest nuclear site in Europe, boasting the world’s most varied array of nuclear facilities on a single site. Workforce numbers fluctuate, but prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the site  employed around 10,000 individuals. The Central Laboratory and headquarters of the UK’s National Nuclear Laboratory are located on the premises. The site is owned by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA), a non-departmental public body of the UK government. From 2008 to 2016, it was managed by a private consortium before control reverted to the government. Consequently, the Site Management Company, Sellafield Ltd, became a subsidiary of the NDA. The decommissioning process of the legacy facilities, which includes structures from the UK’s early efforts to develop an atomic bomb, is expected to be completed by 2120 at an estimated cost of £121 billion.

employed around 10,000 individuals. The Central Laboratory and headquarters of the UK’s National Nuclear Laboratory are located on the premises. The site is owned by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA), a non-departmental public body of the UK government. From 2008 to 2016, it was managed by a private consortium before control reverted to the government. Consequently, the Site Management Company, Sellafield Ltd, became a subsidiary of the NDA. The decommissioning process of the legacy facilities, which includes structures from the UK’s early efforts to develop an atomic bomb, is expected to be completed by 2120 at an estimated cost of £121 billion.

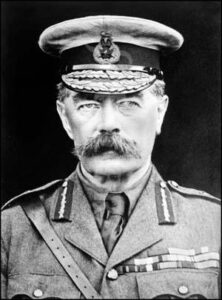

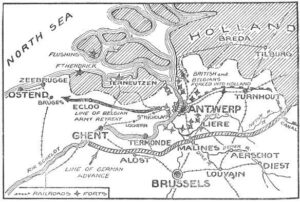

The initiative to send a relief army to support Antwerp did not begin with Winston Churchill, but with Lord Kitchener and the French Government. Churchill was not involved or consulted about the plans until they were well underway, with significant troop movements already in progress or planned. Deciding that he should be brought into the loop, Churchill was summoned to a midnight meeting at Lord Kitchener’s residence on October 2, 1914. It was during this meeting that he fully grasped the progress of the plans to send a relief army to Antwerp, a coordination between Lord Kitchener and the French Government. He learned as well that no definitive commitments had been made to the Belgian Government. On that same afternoon, the Belgian Government had resolved to evacuate Antwerp, pull back the field army from the fort, and effectively abandon the city’s defense.

The initiative to send a relief army to support Antwerp did not begin with Winston Churchill, but with Lord Kitchener and the French Government. Churchill was not involved or consulted about the plans until they were well underway, with significant troop movements already in progress or planned. Deciding that he should be brought into the loop, Churchill was summoned to a midnight meeting at Lord Kitchener’s residence on October 2, 1914. It was during this meeting that he fully grasped the progress of the plans to send a relief army to Antwerp, a coordination between Lord Kitchener and the French Government. He learned as well that no definitive commitments had been made to the Belgian Government. On that same afternoon, the Belgian Government had resolved to evacuate Antwerp, pull back the field army from the fort, and effectively abandon the city’s defense.

The men were deeply troubled by the Belgian Government’s plan. It appeared that just as help was within reach, everything might be sacrificed for a mere three or four days of further resistance. Under these conditions, Churchill proposed to immediately travel to Antwerp to inform the Belgian Government of the ongoing efforts, assess the situation firsthand, and explore how the defense could be extended until a relief force was ready. The others agreed to Churchill’s proposal, and he promptly made his way across the Channel.

The next day, after discussions with the Belgian Government and British Staff officers in Antwerp overseeing the operations, Churchill presented a cautious telegraphic proposal. He avoided any declarations on behalf of the British Government that might encourage the Belgians to hold out for support he couldn’t guaranteed.

Churchill’s proposal was concise and transmitted via telegram. It stated: “The Belgians were to continue the resistance to the utmost limit of their power. The British and French Governments were to say within three days definitely whether they could send a relieving force or not, and what the dimensions of that force would be.

In the event of their not being able to send a relieving force the British Government were to send in any case to Ghent and other points on the line of retreat British troops sufficient to insure the safe retirement of the Belgian field army, so that the Belgian  field army would not be compromised through continuing the resistance on the Antwerp fortress line.

field army would not be compromised through continuing the resistance on the Antwerp fortress line.

Incidentally, we were to aid and encourage the defense of Antwerp by the sending of naval guns, naval brigades, and any other minor measures likely to enable the defenders to hold out the necessary number of days.”

The proposal was contingent upon approval from both parties. It remained unsettled until it received the acceptance of both governments. Upon agreement, Churchill received a telegraph announcing the dispatch of a relief army, including its size and structure, which I was to communicate to the Belgians. Churchill was instructed to do all in his power to sustain the defense in the interim, which he did, disregarding any potential repercussions.

Churchill chose not to recount the well-known military events, but he believed it would be erroneous to view Lord Kitchener’s attempts to relieve Antwerp, in which Churchill had a significant but secondary role, as a venture that resulted solely in adversity.

Churchill believed that military history would deem the outcomes highly favorable to the Western Allies. The significant battle that began on the Aisne was extending daily towards the sea. Sir John French’s forces were assembling and commencing the Battle of Armentières, which led to the pivotal Battle of Ypres, amid an ever-changing situation.

The prolonged defense of Antwerp, even by just a few days, detained substantial German forces near the fortress. The sudden and audacious deployment of a new British division and a British cavalry division at Ghent, among other places, perplexed the cautious German command, causing them to anticipate the arrival of a large force from the sea.

Regardless, their advance was tentative, faced with only weak opposition, and Churchill was convinced that history would confirm, certainly in his view and that of many esteemed military officers of the time, that the

entirety of this operation…the movement of the British and associated French troops…though it failed to save Antwerp, resulted in the great battle being fought along the Yser, rather than twenty or thirty miles to the south, and if that was the case, then the losses sustained by the naval division, fortunately not severe in terms of lives, will undoubtedly have been justified for the greater good.

entirety of this operation…the movement of the British and associated French troops…though it failed to save Antwerp, resulted in the great battle being fought along the Yser, rather than twenty or thirty miles to the south, and if that was the case, then the losses sustained by the naval division, fortunately not severe in terms of lives, will undoubtedly have been justified for the greater good.

In the late 1960s, Chicago was engulfed in turmoil. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, sparked riots throughout the United States, leaving Chicago’s West Side in ruins. Mayor Richard J Daley infamously ordered a “shoot to kill” directive for arsonists. It was a vast difference from the way riots were handled in the 2020 era, after the killing of George Floyd, when riots were not only allowed, but encouraged. Nevertheless, in Chicago in 1968, chaos reigned then and again during the Democratic National Convention a few months later, culminating in a confrontation between protesters and police that a national commission later described as a “police riot.”

In the late 1960s, Chicago was engulfed in turmoil. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, sparked riots throughout the United States, leaving Chicago’s West Side in ruins. Mayor Richard J Daley infamously ordered a “shoot to kill” directive for arsonists. It was a vast difference from the way riots were handled in the 2020 era, after the killing of George Floyd, when riots were not only allowed, but encouraged. Nevertheless, in Chicago in 1968, chaos reigned then and again during the Democratic National Convention a few months later, culminating in a confrontation between protesters and police that a national commission later described as a “police riot.”

The year 1969 seemed to mark a period of calm until the commencement of a conspiracy trial targeting the Democratic convention protest organizers, which ignited a new phase in the clash between the counterculture and the “establishment.” This battle shifted from the streets to the realm of public opinion. While the defendants attempted to mock and censure the government, represented by Judge Julius Hoffman in the courtroom, a separate faction of youth chose to take a more extreme stance in protesting the government and the ongoing Vietnam conflict. Their strategy was to “bring the war home” through four “Days of Rage.” It amazes me that these people think that destroying their own “home turf” and the businesses that are there, would somehow generate support for their cause…and then they want the American people to pay for the repairs!!

“Every day that the war [in Vietnam] went on, two thousand innocent people would be killed. So, there was a kind of urgency that took over. And in that context, we faced each other and tried to figure out, what do you do to end a war? How do you stop it,” Bill Ayers, an organizer of the Days of Rage, told WTTW decades later. Ayers and his fellow protesters belonged to the activist group Students for a Democratic Society but were starting to diverge from the main SDS body. They named themselves the Weathermen, inspired by a lyric in a Bob Dylan song, “Subterranean Homesick Blues” which stated, “You don’t need a weather man to know which way the wind blows.”

The Weathermen believed that the peaceful methods of other SDS factions were ineffective, so they organized for thousands to converge on Chicago, coinciding with the commencement of the Chicago Eight conspiracy trial two weeks later. “A huge outpouring of militance, of young people. We felt that we ought to call a demonstration in which we weren’t contained and controlled,” Ayers said. However, as the Days of Rage commenced, the Weathermen discovered their support was significantly less than anticipated. On October 8, 1969, they assembled in Lincoln Park to initiate their violent protests—donning football helmets and shoulder pads, and arming themselves with steel pipes, chains, slingshots, and baseball bats—yet only a few hundred individuals participated, a stark contrast to the fifty thousand they had expected.

On that initial evening in 1969, protesters headed south toward the Drake Hotel, the residence of Judge Hoffman, shattering the windows of vehicles and shops in their path. Following their assault on police barricades, law enforcement quelled the disturbances with countermeasures, deploying tear gas, nightsticks, and firearms. Although some Weathermen were shot and officers sustained injuries, there were no fatalities. “The thought of the Chicago Police Department and the mayor of the city of Chicago was to try to avoid confrontation,” Richard Elrod, a state legislator and attorney for the city who had been tasked with handling the riots, told WTTW decades later. Ayers disagreed, saying, “I don’t think the police, or the city learned a thing between ’68 and ’69.” The police faced widespread criticism for their management of the protests at the Democratic convention the previous year.

Other activists criticized the tactics of the Weathermen. “We thought it was off the wall,” Carl Davidson, a leader of SDS, told WTTW. “We thought it was silly, counterproductive, that it wasn’t going anywhere. That’s the best we thought of it.” A different branch of SDS coordinated peaceful protests with the Black Panthers against the Vietnam War and persistent racial inequality, attracting thousands of participants. However, it was the minor yet violent actions of the Weathermen that captured media attention. Even Ayers later expressed doubt about the riots, saying “I don’t think that the Days of Rage was a particularly smart or effective tactic. I think it was a very difficult time to know what to do, but we were determined to see through our strategy of militant opposition and trying to mobilize all of the militants to come to Chicago to display their anger, their outrage, and their deep opposition to this war. That was a colossal failure, in the sense that we didn’t mobilize lots of people to come.”

The subsequent Days of Rage were less intense, yet on October 11, the Weathermen gathered at a statue of a policeman they had previously bombed in the lead-up to the Days of Rage and proceeded into the Loop. They once again engaged with the police, an event described in a 1994 retrospective article by the Chicago Tribune as a “vicious melee that resulted in nearly 300 arrests, 48 police injuries and unknown more to protesters.” In the midst of the confrontation, Richard Elrod sustained a neck injury that resulted in paralysis from the neck down, although he later regained some movement but continued to suffer partial paralysis. Elrod reported that he had attempted to tackle Brian Flanagan, a 22-year-old protester, who retaliated by kicking him in the neck with steel-toed boots. Flanagan, who was ultimately acquitted on all counts, contended that Elrod collided with a concrete wall during his attempted tackle. The subsequent year, Elrod was elected as the Cook County sheriff and subsequently ascended to the position of a Circuit Court judge.

Former state legislator and Cook County sheriff Richard Elrod, who is shown in a photo from the early 2000s, suffered a broken neck during the Days of Rage. That confrontation marked the end of the Days of Rage. The Weathermen, in certain respects, “brought the war home.” However, their protests might have inadvertently enhanced the police’s reputation and undermined the causes they supported by linking anti-war and anti-racism demonstrations with violence in public perception. Following the Days of Rage, a lengthy magazine feature overtly supportive of the police and the city appeared in the Chicago Tribune, which asserted that “the police, widely condemned scarcely a year ago for their conduct during the Democratic convention, had never enjoyed so much public acclaim.”

Months later, the Weathermen were forced underground when a bomb they were constructing inadvertently detonated, killing three of their leaders in New York City. In the following decades, participants of the Days of Rage began to turn themselves in to the authorities. One of the last to do so was Jeffrey David Powell, who surrendered in 1994 and was sentenced to a fine and 18 months of probation. Ayers, along with his wife Bernardine Dohrn, another member of the Weathermen, surrendered in 1981. While Dohrn was fined and placed on probation, charges against Ayers, whose father was a president at Commonwealth Edison, were dismissed due to illicit FBI methods used against him. He went on to become a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and gained brief national attention during the 2008 presidential election for his association with Barack Obama. Dohrn secured a position as a professor at the Children and Family Justice Center at Northwestern University’s Law School.

The Days of Rage had receded into the annals of history. However, as reported by the Chicago Tribune at the time of Powell’s surrender, “the Days of Rage symbolized a marked fissure in American society, the end of the carefree ‘60s, when rich, white college kids clashed with police, their parents, the government in protest against the Vietnam War, racial intolerance and just about everything else that had served as the status quo.”

The Battle of Wake Island was a significant conflict in the Pacific theater of World War II, occurring on Wake Island. The attack began simultaneously with the assault on Pearl Harbor’s naval and air bases in Hawaii on the morning of December 8, 1941 (December 7th in Hawaii) and concluded on December 23rd with the American forces capitulating to the Empire of Japan. The battle took place on the atoll comprising Wake Island and its smaller islets, Peale and Wilkes, involving air, land, and sea forces of the Japanese Empire and the United States, with a notable presence of Marines from both nations. The Japanese forces were formidable, and the majority of the surviving Americans were transported from the island to POW camps by the Japanese. Ninety-seven were left behind to be used as forced labor. The Allies’ response involved intermittent bombing of the island, but no further land invasions occurred. This was in line with a broader Allied strategy to isolate certain Japanese-occupied islands in the South Pacific, effectively leaving them to wither in isolation.

The Battle of Wake Island was a significant conflict in the Pacific theater of World War II, occurring on Wake Island. The attack began simultaneously with the assault on Pearl Harbor’s naval and air bases in Hawaii on the morning of December 8, 1941 (December 7th in Hawaii) and concluded on December 23rd with the American forces capitulating to the Empire of Japan. The battle took place on the atoll comprising Wake Island and its smaller islets, Peale and Wilkes, involving air, land, and sea forces of the Japanese Empire and the United States, with a notable presence of Marines from both nations. The Japanese forces were formidable, and the majority of the surviving Americans were transported from the island to POW camps by the Japanese. Ninety-seven were left behind to be used as forced labor. The Allies’ response involved intermittent bombing of the island, but no further land invasions occurred. This was in line with a broader Allied strategy to isolate certain Japanese-occupied islands in the South Pacific, effectively leaving them to wither in isolation.

On October 5, 1943, American naval aircraft from the USS Yorktown attacked Wake Island. On October 7, 1943, Rear Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara, commander of the Japanese garrison on the island, orders the execution of a civilian accused of stealing, and 97 Americans POWs, claiming they were trying to make radio contact with US forces, and a civilian accused of stealing. Initially, the 97 POWs were detained to be used as forced labor. Anticipating an invasion, Sakaibara commanded their execution. They were led to the island’s northern end, blindfolded, and shot with a machine gun. One prisoner, whose name remains unknown, escaped and etched “98 US PW 5-10-43” into a large coral rock near the hastily dug mass grave. This American was later recaptured, and Sakaibara personally beheaded him with a katana. The etched message remains visible, marking a somber landmark on Wake Island to this day. The Wake Island Massacre was an outrage.

The Pacific war finally drew to a close starting in August 1945, and the Emperor of Japan announced the surrender to the Japanese people and the agreement was formally signed by September 2, 1945. On September 4, 1945, the remaining Japanese garrison surrendered to a detachment of United States Marines under the command of Brigadier General Lawson H. M. Sanderson, with the handover being officially conducted in a brief ceremony aboard the destroyer escort USS Levy. Earlier, the garrison received news that Imperial Japan’s defeat was imminent, so the mass grave was quickly exhumed, and the bones were moved to the US cemetery that had been established on Peacock Point after the invasion, with wooden crosses erected in preparation for the expected arrival of US forces. During the initial interrogations, the Japanese claimed that the remaining 98 Americans on the island were mostly killed by an American bombing raid, though some escaped and fought to the death after being cornered on the beach at the north end of Wake Island. Several Japanese officers in American custody committed suicide over the incident, leaving written statements that incriminated Sakaibara. Sakaibara and his subordinate, Lieutenant Commander Tachibana, were later sentenced

to death after conviction for this and other war crimes. Sakaibara was executed by hanging in Guam on June 19, 1947, while Tachibana’s sentence was commuted to life in prison. The remains of the murdered civilians were exhumed and reburied at Section G of the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, which is commonly known as Punchbowl Crater, on Honolulu.

to death after conviction for this and other war crimes. Sakaibara was executed by hanging in Guam on June 19, 1947, while Tachibana’s sentence was commuted to life in prison. The remains of the murdered civilians were exhumed and reburied at Section G of the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, which is commonly known as Punchbowl Crater, on Honolulu.

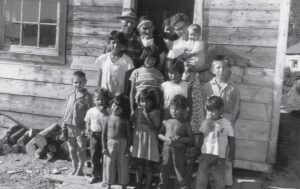

The Sixties Scoop, often referred to simply as The Scoop, was a time when policies in Canada allowed child welfare authorities to remove Indigenous children from their families and communities to place them in foster homes. These children were then adopted by white families. Although it is called the Sixties Scoop, this practice started in the mid-to-late 1950s and continued until the 1980s. There was no given indication that these children were neglected or mistreated, just that they were Indigenous, and supposedly, therefore would be better off in the care of white families. During those years, an estimated 20,000 Indigenous children were removed from their families and placed predominantly with white middle-class families.

The Sixties Scoop, often referred to simply as The Scoop, was a time when policies in Canada allowed child welfare authorities to remove Indigenous children from their families and communities to place them in foster homes. These children were then adopted by white families. Although it is called the Sixties Scoop, this practice started in the mid-to-late 1950s and continued until the 1980s. There was no given indication that these children were neglected or mistreated, just that they were Indigenous, and supposedly, therefore would be better off in the care of white families. During those years, an estimated 20,000 Indigenous children were removed from their families and placed predominantly with white middle-class families.

The program’s policies were not uniform, with each province implementing distinct foster programs and adoption policies. Saskatchewan was unique in having the targeted Indigenous transracial adoption program known as the Adopt Indian Métis (AIM) Program. The term “Sixties Scoop” was first used in the early 1980s by social workers from the British Columbia Department of Social Welfare to describe the practice of child apprehension by their department. This term made its initial appearance in print in a 1983 report by the Canadian Council on Social Development, entitled “Native Children and the Child Welfare System.” Researcher Patrick Johnston cited the term’s origin and utilized it in his report. This term is akin to “Baby Scoop Era,” denoting the time from the late 1950s to the 1980s when many children were removed from unmarried mothers for adoption. These mothers were given no choice in the matter.

The government policies responsible for the Sixties Scoop were abandoned in the mid-1980s following resolutions passed by Ontario chiefs and severe condemnation from a Manitoba judicial inquiry. The inquiry, led by Associate Chief Judge Edwin C. Kimelman, culminated in the release of “No Quiet Place / Review Committee on Indian and Métis Adoptions and Placements,” commonly referred to as the “Kimelman Report.” Numerous lawsuits have been initiated in Canada by individuals who were part of the Sixties Scoop, including class-action suits in five provinces, such as the one initiated in British Columbia in 2011. Chief Marcia Brown Martel of the Beaverhouse First Nation was the lead plaintiff in the Ontario class-action suit filed in 2009. On February 14, 2017, Justice Edward Belobaba of the Ontario Superior Court found the government responsible for damages caused by the Sixties Scoop. Subsequently, on October 6, 2017, an $800-million settlement was disclosed for the Martel case. Currently, Métis and non-status First Nations individuals are not included in the settlement, prompting the National Indigenous Survivors of Child Welfare Network…an organization led by survivors of the Sixties Scoop in Ottawa…to call for the rejection of the settlement unless it encompasses all Indigenous individuals who were removed from their homes and placed into forced adoption.

The Sixties Scoop began during a period when Indigenous families were already grappling with the consequences of the Canadian Indian residential school system. This network of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples adversely affected their social, economic, and living conditions. The residential school system remained operational until the closure of the last school in 1996. Established by the federal government and managed by various churches, the system’s goal was to assimilate Aboriginal children by teaching them Euro-Canadian and Christian values. It enforced policies that prohibited the children from speaking their native languages, communicating with their families, or practicing their cultural traditions. Survivors of residential schools have spoken out about the physical, spiritual, sexual, and psychological abuse they endured from the staff. The enduring cultural impact on First Nations, Métis, and Inuit families and communities is both widespread and profound.

The Sixties Scoop involved the forced removal of children from their Indigenous lands and communities, often without the consent or knowledge of their families or tribes. Siblings were frequently separated and sent to different areas to prevent any communication with their relatives. These children were denied knowledge of their true nationality, history, or family ties. If a child sought to learn about their cultural identity, they required consent from their biological parents. However, due to the government’s efforts to sever ties between the children and their biological families, access to their birth records was impossible. Consequently, while the children might have suspected their cultural heritage, they had no means to verify it with concrete evidence.

The Canadian government began the process of closing the mandatory residential school system in the 1950s and 1960s, believing that Aboriginal children would receive a superior education within the public school system. A summary states: “This transition to provincial services led to a 1951 [Indian Act] amendment that enabled the province to provide services to Aboriginal people where none existed federally. Child protection was one of these areas. In 1951, twenty-nine Aboriginal children were in provincial care in British Columbia; by 1964, that number was 1,466. Aboriginal children, who had comprised only 1 percent of all children in care, came to make up just over 34 percent.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada, established as part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, was tasked with recording the experiences of Indigenous children in residential schools. Its mission was to disseminate the truths of survivors, their families, communities, and all those impacted, to the Canadian populace. The TRC’s final report, released in 2015, details these findings: “By the end of the 1970s, the transfer of children from residential schools was nearly complete in Southern Canada, and the impact of the Sixties Scoop was in evidence across the country.” First Nations have persistently resisted such policies through various means, including legal challenges (Natural Parents v. Superintendent of Child Welfare, 1976, 60 D.L.R. 3rd 148 S.C.C) and the establishment of their own policies, like the Spallumcheen Indian Band’s by-law to manage its child welfare program, achieving varying levels of success.

In response to the loss of their children and the subsequent cultural genocide, First Nations communities took

action by repatriating children from failed adoptions and striving to reclaim authority over their children’s welfare practices. This movement began in 1973 with the Blackfoot (Siksika) child welfare agreement in Alberta. Currently, there are approximately 125 First Nations Child and Family Service Agencies in Canada, operating under a variety of agreements that grant them authority from provincial governments to offer services, with funding provided by the federal government.

action by repatriating children from failed adoptions and striving to reclaim authority over their children’s welfare practices. This movement began in 1973 with the Blackfoot (Siksika) child welfare agreement in Alberta. Currently, there are approximately 125 First Nations Child and Family Service Agencies in Canada, operating under a variety of agreements that grant them authority from provincial governments to offer services, with funding provided by the federal government.

My uncle, Lester “Jim” Wolfe was in the Army during World War II, and as such, was among those who stormed the beaches of Normandy, France on D-Day (June 6, 1944), while my dad, Allen Spencer, his future brother-in-law, was among the B-17s flying cover in the skies above. Thankfully, both of them made it home, and became the men they were destined to be. I really can’t imagine growing up without knowing my Uncle Jim. He was a great guy, with a great sense of humor. He saw a lot of things in his lifetime, and so, he always had great stories to tell. To my child’s mind, my uncle seemed very knowledgeable in things, as did my dad. It was a different era than that of my own, and they knew different things as a result. I guess that is why they always seemed so wise to me.

My uncle, Lester “Jim” Wolfe was in the Army during World War II, and as such, was among those who stormed the beaches of Normandy, France on D-Day (June 6, 1944), while my dad, Allen Spencer, his future brother-in-law, was among the B-17s flying cover in the skies above. Thankfully, both of them made it home, and became the men they were destined to be. I really can’t imagine growing up without knowing my Uncle Jim. He was a great guy, with a great sense of humor. He saw a lot of things in his lifetime, and so, he always had great stories to tell. To my child’s mind, my uncle seemed very knowledgeable in things, as did my dad. It was a different era than that of my own, and they knew different things as a result. I guess that is why they always seemed so wise to me.

While he had a lot of wisdom, Uncle Jim was also a great comedian too. He was always making jokes and loved  to make and hear people laugh. Uncle Jim was a master storyteller, the finest there was. Whenever he began his tales, we’d gather around, eyes wide with amazement. It was always a mystery whether his stories were drawn from life or were pre fiction…until the punchline came. At that moment, we’d burst into laughter, exclaiming, “Oh! Uncle Jim!” He delighted in our reactions, which brought him great amusement. And on the topic of amusement, Uncle Jim was an old hand at tickling. He’d chase and tickle us whenever we pestered him…which, of course, meant we always did. We’d scamper off, trying to escape, though we never really did. Uncle Jim’s heart was as kind as his spirit was playful.

to make and hear people laugh. Uncle Jim was a master storyteller, the finest there was. Whenever he began his tales, we’d gather around, eyes wide with amazement. It was always a mystery whether his stories were drawn from life or were pre fiction…until the punchline came. At that moment, we’d burst into laughter, exclaiming, “Oh! Uncle Jim!” He delighted in our reactions, which brought him great amusement. And on the topic of amusement, Uncle Jim was an old hand at tickling. He’d chase and tickle us whenever we pestered him…which, of course, meant we always did. We’d scamper off, trying to escape, though we never really did. Uncle Jim’s heart was as kind as his spirit was playful.

Uncle Jim was the kind of person who would help anyone in need, whether they were neighbors, friends, or even strangers. His generosity knew no bounds, and he was always ready to offer his assistance. His love for his family was his “above all” priority. He would protect his wife and children at all costs, both in words and actions. He was utterly devoted to them. When he decided to purchase land in Washington to build his final home, he ensured there was enough space for each of his children to have a place of their own nearby. He was determined that none of them would ever be without a home. The property he chose was atop a mountain, offering some of the most stunning views during the ascent. Even in his later years, as Alzheimer’s Disease necessitated his stay in a nursing home, he maintained his happy spirit. He delighted in brightening the day of the nursing staff and

visitors alike, often engaging in harmless “mischief” around the nurses’ station. My sisters and I continue to hold him dear in our hearts. Thoughts of him always bring smiles to our faces. Uncle Jim passed away in 2013, reuniting with his beloved wife, my Aunt Ruth, and other departed family members. We’re comforted by the belief that they’re joyfully together, and we look forward to the day we’ll all be reunited. Today marks what would have been Uncle Jim’s 103rd birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Jim!! We love and miss you very much!!

visitors alike, often engaging in harmless “mischief” around the nurses’ station. My sisters and I continue to hold him dear in our hearts. Thoughts of him always bring smiles to our faces. Uncle Jim passed away in 2013, reuniting with his beloved wife, my Aunt Ruth, and other departed family members. We’re comforted by the belief that they’re joyfully together, and we look forward to the day we’ll all be reunited. Today marks what would have been Uncle Jim’s 103rd birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Jim!! We love and miss you very much!!

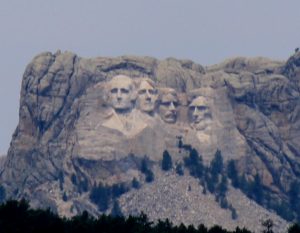

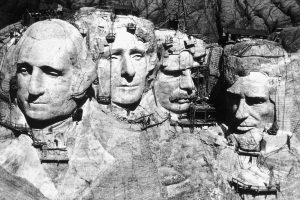

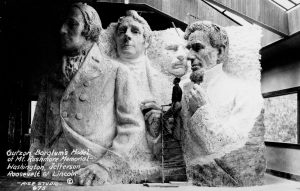

One of the most iconic monuments in the United States, in my opinion is that of Mount Rushmore. I’m sure some people might not agree with me on that, but I have been to Mount Rushmore more times than I could possibly count, and it just never gets old. The monument was the vision of Doane Robinson, a South Dakota historian who was looking to draw more visitors to the state. While that was a cool idea, it was dwarfed, in the end, by the absolute grandeur of the finished product. Maybe it was the vision of the sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, who Robinson commissioned to chisel the faces into the mountain, or maybe it was because it would transform a mountain into an awesome tribute to four really great presidents. I can’t say for sure, but the monument ended up being so much more than a tourist attraction. Every time I am there, I feel the awesomeness of the place, almost as if it is hallowed ground…though not in the Biblical sense.

One of the most iconic monuments in the United States, in my opinion is that of Mount Rushmore. I’m sure some people might not agree with me on that, but I have been to Mount Rushmore more times than I could possibly count, and it just never gets old. The monument was the vision of Doane Robinson, a South Dakota historian who was looking to draw more visitors to the state. While that was a cool idea, it was dwarfed, in the end, by the absolute grandeur of the finished product. Maybe it was the vision of the sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, who Robinson commissioned to chisel the faces into the mountain, or maybe it was because it would transform a mountain into an awesome tribute to four really great presidents. I can’t say for sure, but the monument ended up being so much more than a tourist attraction. Every time I am there, I feel the awesomeness of the place, almost as if it is hallowed ground…though not in the Biblical sense.

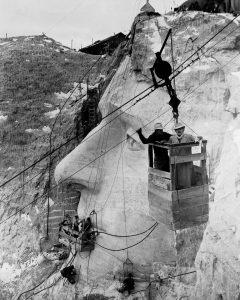

The sculpting of Mount Rushmore was a monumental task, particularly in 1927. Nevertheless, the carving began on October 4th on the likenesses of the four great men of Mount Rushmore, located in the Black Hills National Forest of South Dakota. The project was to be far from quickly finished. Instead, it would take an additional 12 years to complete the granite likenesses of four esteemed American presidents…George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. Each time a likeness was completed, it was big news, and people came from miles around to watch the unveiling ceremony. Of course, the project was not without conflict. The Lakota Sioux people, who consider the Black Hills to be sacred ground, strongly opposed the project. The mountain was previously part of the Great Sioux Reservation before being taken away  from them by the US government. Nevertheless, there were no skirmishes over the project, and these days, the likeness of Crazy Horse is also being carved into a mountain in the Black Hills.

from them by the US government. Nevertheless, there were no skirmishes over the project, and these days, the likeness of Crazy Horse is also being carved into a mountain in the Black Hills.

The first face “chiseled” by Borglum, was that of George Washington. Initially, Borglum sculpted the head in an egg shape and added the features afterward. The plan was to place Thomas Jefferson’s likeness to the right of Washington, but after two years, it developed severe cracks. The workers were forced to remove the damaged sculpture with dynamite. They tried going deeper, but the kept coming up with more quartz, which was unsuitable for the enduring sculpture that today exists on Mount Rushmore. So, Borglum repositioned Jefferson on Washington’s left side and started again.

Washington’s face was completed in 1934. Jefferson’s was dedicated in 1936…with then…president Franklin Roosevelt in attendance. Lincoln’s likeness was completed a year later. In 1939, Teddy Roosevelt’s face was completed. The project, which cost $1 million, was funded primarily by the federal government. When we think of sculpting in stone, we think of hammers and chisels, but much of Mount Rushmore was “sculpted” with dynamite. With 450,000 tons of granite to be removed, chisels were definitely not going to be enough. Throughout the fourteen years of carving, from 1927 to 1941, nearly 400 workers, including both men and women, labored at the memorial. The work was demanding, the hours extensive, the wages modest, and job security was unpredictable. Even under severe and perilous conditions, there were no fatalities during the carving process. While for some, this work represented merely a job, for others, it evolved into a profound vocation. For those that embraced the project, I can imagine that they somehow felt the same sense of this being hallowed ground that I feel each time I’m there.

At the time of Borglum’s death, the sculpture was not finished. He continued to touch up his work at Mount Rushmore until he died suddenly in 1941. Borglum had originally hoped to also carve a series of inscriptions into the mountain, outlining the history of the United States. After his passing, his son Lincoln Borglum finished

the sculpture to its current point. It isn’t exactly the sculpture Gutzon Borglum has imagined, because it was to have featured the presidents to their waists, but I think it is perfect as it stands today, from its four carved heads to the secret room, known as “The Hall of Records,” behind the structure, that no one is permitted to see without an act of Congress. That is something I would love to be allowed to see someday. As it stands, it too remains unfinished.

the sculpture to its current point. It isn’t exactly the sculpture Gutzon Borglum has imagined, because it was to have featured the presidents to their waists, but I think it is perfect as it stands today, from its four carved heads to the secret room, known as “The Hall of Records,” behind the structure, that no one is permitted to see without an act of Congress. That is something I would love to be allowed to see someday. As it stands, it too remains unfinished.

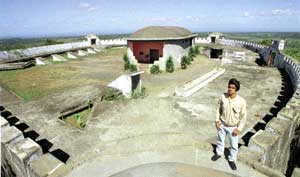

The Battle of Coyotepe Hill marked a major conflict in the United States’ occupation of Nicaragua, spanning from August to November 1912. This clash was part of the insurrection led by General Luis Mena Vado, the Minister of War, against President Adolfo Díaz Recinos’ administration. Coyotepe is an ancient fortress perched atop a 500-foot hill, commanding a view of the strategic railway line near Masaya, situated approximately halfway between Managua and Granada in Nicaragua.

The Battle of Coyotepe Hill marked a major conflict in the United States’ occupation of Nicaragua, spanning from August to November 1912. This clash was part of the insurrection led by General Luis Mena Vado, the Minister of War, against President Adolfo Díaz Recinos’ administration. Coyotepe is an ancient fortress perched atop a 500-foot hill, commanding a view of the strategic railway line near Masaya, situated approximately halfway between Managua and Granada in Nicaragua.

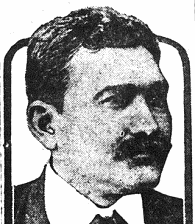

Adolfo Díaz Recinos was born on July 15, 1875, in Alajuela, Costa Rica, and he served as the President of Nicaragua from May 9, 1911, to January 1, 1917, and once more from November 14, 1926, to January 1, 1929. A native of Costa Rica to Nicaraguan parents, he was employed as a secretary by the La Luz y Los Angeles Mining Company. This American enterprise, incorporated in Delaware, owned extensive gold mines near Siuna in Eastern Nicaragua. Díaz Recinos played a pivotal role in directing funds to the insurrection against Liberal President José Santos Zelaya, who had angered the United States through his negotiations with Germany and Japan regarding the revival of the Nicaragua Canal project.

Luis Mena Vado, born in 1865, served as the President of Nicaragua from August 27 to 30, 1910, following the  collapse of General José Santos Zelaya’s government. He subsequently assumed the role of acting President during a rebellion. A conservative, Mena Vado was a member of the coalition government alongside liberal Juan Jose Estrada and fellow conservatives Emiliano Chamorro and Adolfo Diaz Recinos.

collapse of General José Santos Zelaya’s government. He subsequently assumed the role of acting President during a rebellion. A conservative, Mena Vado was a member of the coalition government alongside liberal Juan Jose Estrada and fellow conservatives Emiliano Chamorro and Adolfo Diaz Recinos.

From October 2 to 4, 1912, Nicaraguan rebels commanded by General Benjamín Zeledón held positions at Coyotepe and Barranca fort, strategic locations overlooking a vital railway line, and refused to surrender to the forces of President Adolfo Díaz Recinos. Major Smedley Butler of the US Marines, who had previously clashed with Zeledón’s forces on September 19th, led his battalion back from their recent victory in Granada, Nicaragua, on October 3rd and bombarded the insurgents’ stronghold at Coyotepe.

In the pre-dawn hours of October 4th, Butler’s battalion, along with two Marine battalions and another from the USS California under the command of Marine Colonel Joseph H Pendleton, coordinated an assault from various positions to seize the hill. Zeledón was killed in the conflict…most likely by his own troops. With the capture of

León, Nicaragua two days later by US Marines and the recapture of Masaya by Nicaraguan government troops, the Nicaraguan revolution of 1912 was essentially over. During the Somoza dictatorship the fortress was used as a prison. Occasionally, various dissidents are imprisoned there would be taken from the fortress in a helicopter and dropped into a nearby volcano.

León, Nicaragua two days later by US Marines and the recapture of Masaya by Nicaraguan government troops, the Nicaraguan revolution of 1912 was essentially over. During the Somoza dictatorship the fortress was used as a prison. Occasionally, various dissidents are imprisoned there would be taken from the fortress in a helicopter and dropped into a nearby volcano.

For a number of years, I took my dad, Allen Spencer, who was a top turret gunner and flight engineer on a B-17G during World War II, to see the vintage planes when they came into Casper, Wyoming. Included in those old B-17s was the infamous Nine-O-Nine. Dad loved them all, and it was a special time for us. We crawled through those old planes, and Dad showed me his station, as well as the others on the Flying Fortress. Dad passed away on December 12, 2007, and I think of those special outings every time I see a B-17 flying overhead. The sightings are becoming fewer and further between, sadly. It’s quickly becoming the second end of the World War II era.

For a number of years, I took my dad, Allen Spencer, who was a top turret gunner and flight engineer on a B-17G during World War II, to see the vintage planes when they came into Casper, Wyoming. Included in those old B-17s was the infamous Nine-O-Nine. Dad loved them all, and it was a special time for us. We crawled through those old planes, and Dad showed me his station, as well as the others on the Flying Fortress. Dad passed away on December 12, 2007, and I think of those special outings every time I see a B-17 flying overhead. The sightings are becoming fewer and further between, sadly. It’s quickly becoming the second end of the World War II era.

The Nine-O-Nine was privately owned by the Collings Foundation and on October 2, 2019, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress crashed at Bradley International Airport, Windsor Locks, Connecticut. Sadly, seven of the thirteen people on board were killed, and the other six, as well as one person on the ground, were injured. The precious Nine-O-Nine was destroyed by fire, with only a portion of one wing and the tail remaining. I couldn’t believe it when I heard. It was so tragic.

Before the accident, the Collings Foundation operated the aircraft under the Living History Flight Experience, an FAA program permitting vintage military aircraft owners to provide compensated rides. The Foundation’s executive director, Rob Collings, had sought amendments to permit guests to handle the aircraft’s controls, contending that the FAA’s interpretation of the program’s regulations was overly stringent.

The “living history” flight was delayed by 40 minutes due to a problem starting one of the engines. The pilot shut down the other engines and used a spray can to remove moisture before starting the flight. Departing from Bradley International Airport in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, at 9:48am local time, the aircraft was on a local flight with three crew members and ten passengers. An engine was observed sputtering and emitting smoke. At 9:50am, the pilot reported an issue with the plane’s Number 4 engine, located on the outer right wing. He instructed the crew chief, who also served as the loadmaster, to have the passengers return to their seats. Then, the pilot shut down the Number 4 engine. The control tower cleared the airspace for the aircraft to make an emergency landing on Runway 6. Approaching low, the Nine-O-Nine landed 1,000 feet before the runway, struck the Instrument Landing System (ILS) antenna array, veered right off the runway, crossed a grassy area and a taxiway, and collided with a de-icing facility at 9:54am, bursting into flames. A Connecticut Air National Guardsman, despite sustaining a broken arm and collarbone, successfully opened an escape hatch following the plane crash. Meanwhile, an airport worker, who was in the building struck by the plane, rushed to the crash site to assist in extracting injured passengers from the fiery wreckage. This individual incurred serious burns to his hands and arms and was subsequently transported to the hospital by ambulance. The pilot and co-pilot, aged 75 and 71, were among the seven fatalities. Additionally, one individual on the ground sustained injuries. The airport remained closed for three and a half hours after the incident.

According to the final report released by the NTSB on May 17, 2021, the probable cause of the crash was: “The pilot’s failure to properly manage the airplane’s configuration and airspeed after he shut down the Number 4 engine following its partial loss of power during the initial climb. Contributing to the accident was the inadequate

maintenance of the airplane while it was on tour, which resulted in the partial loss of power to the Numbers 3 and 4 engines; the ineffective safety management system (SMS) of the Collings Foundation, which failed to identify and mitigate safety risks; and the FAA’s inadequate oversight of the Collings Foundation’s SMS.”

maintenance of the airplane while it was on tour, which resulted in the partial loss of power to the Numbers 3 and 4 engines; the ineffective safety management system (SMS) of the Collings Foundation, which failed to identify and mitigate safety risks; and the FAA’s inadequate oversight of the Collings Foundation’s SMS.”

The quiet morning of October 1, 1987, was suddenly shattered at 7:42 am by the ominous shaking of a 6.1 earthquake. The quake, located in Whittier, California, killed 6 people and injured 100 more that fateful day. The quake, named the 1987 Whittier Narrows Earthquake, lasted 30 seconds, violently waking residents from sleep, with items tumbling to the floor. The quake ruptured gas lines, sparking several fires. As is usually the case, falling debris was the cause of the loss of lives and the injuries. In addition, there were significant highway disruptions. Remarkably, no substantial building collapses occurred despite the intense shaking. It was the largest quake to hit Southern California since 1971. Nevertheless, it was not nearly as damaging as the Northridge quake that would devastate parts of Los Angeles seven years later.

The quiet morning of October 1, 1987, was suddenly shattered at 7:42 am by the ominous shaking of a 6.1 earthquake. The quake, located in Whittier, California, killed 6 people and injured 100 more that fateful day. The quake, named the 1987 Whittier Narrows Earthquake, lasted 30 seconds, violently waking residents from sleep, with items tumbling to the floor. The quake ruptured gas lines, sparking several fires. As is usually the case, falling debris was the cause of the loss of lives and the injuries. In addition, there were significant highway disruptions. Remarkably, no substantial building collapses occurred despite the intense shaking. It was the largest quake to hit Southern California since 1971. Nevertheless, it was not nearly as damaging as the Northridge quake that would devastate parts of Los Angeles seven years later.

Southern California was shaken by a prolonged series of aftershocks in the days following the earthquake. Many people were hesitant to return to their homes, so they chose to camp in public parks for an extended period of time, until things settled down again. As a safety measure, hospitals were preemptively evacuated. While there were isolated incidents of looting amidst the turmoil, they were not widespread.

The earthquake occurred on a blind thrust fault. A blind thrust earthquake happens along a thrust fault that leaves no signs on the Earth’s surface, which is why it’s termed “blind.” These faults, hidden from view, elude standard geological mapping on the surface. Occasionally, they are detected incidentally during oil exploration with seismic methods; otherwise, their presence may remain unsuspected…until the quake occurs.

Whittier, a small town located south of Los Angeles, is primarily known as the birthplace of President Richard Nixon. However, Nixon’s birth was not the only time Whittier was in the news. In fact, this quake was not the first earthquake to strike Whittier. The 1929 Whittier earthquake struck on July 8, registering a local magnitude of 4.7 and a maximum intensity of VII (Very Strong) on the Mercalli intensity scale. The tremor, with a depth of 8.1 miles, was felt most acutely southwest of the city, where it caused significant damage to a school and two houses and led to the collapse of chimneys in other homes. In Santa Fe Springs, oil derricks were affected, and minor ground fissures were observed. That earthquake’s impact was noted from Mount Wilson to Santa Ana, and from Hermosa Beach to Riverside, with numerous aftershocks continuing until early 1931.

The 7:42 am quake was the most intense in the Los Angeles region since the 1971 San Fernando quake, reaching as far as San Diego, San Luis Obispo, and Las Vegas. Communications and local media were disrupted, power outages occurred, and many early workers were trapped in inoperative elevators. Additional

devastations included several water and gas main ruptures, broken windows, and partial ceiling collapses. Similar to the San Fernando quake, transportation was impacted, with the Santa Ana and San Gabriel River Freeways closed near Santa Fe Springs due to dislodged concrete and visible cracks. Damage from the 1987 Whittier earthquake is estimated at $100 million.

devastations included several water and gas main ruptures, broken windows, and partial ceiling collapses. Similar to the San Fernando quake, transportation was impacted, with the Santa Ana and San Gabriel River Freeways closed near Santa Fe Springs due to dislodged concrete and visible cracks. Damage from the 1987 Whittier earthquake is estimated at $100 million.