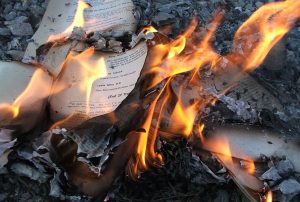

book burning

Book burning is the ritual destruction by fire of books or other written materials. This practice is usually carried out in a public place, so as to further destroy any sense of control of one’s own life. The burning of books represents an element of censorship and usually proceeds from a cultural, religious, or political opposition to the materials in question. Sometimes those burning the books think they are “protecting” the people from something they deem to be evil, but more often, the books simply don’t agree with the agenda of the controlling group. Such was the case with the most famous book burning, which took place under the Nazi regime on May 10, 1933. The May 1933 book burning in Nazi Germany was preceded in nineteenth century Germany. In 1817, German student associations (Burschenschaften) chose the 300th anniversary of Luther’s 95 Theses to hold a festival at the Wartburg, a castle in Thuringia where Luther had sought sanctuary after his excommunication. The students were demonstrating for a unified country. Germany was then a patchwork of states. During the protest, the students burned anti-national and reactionary texts and literature which the students viewed as “Un-German” in nature or content. I wonder if they had any idea that the freedom to protest was the very thing they were looking to take away in the future Germany.

Book burning is the ritual destruction by fire of books or other written materials. This practice is usually carried out in a public place, so as to further destroy any sense of control of one’s own life. The burning of books represents an element of censorship and usually proceeds from a cultural, religious, or political opposition to the materials in question. Sometimes those burning the books think they are “protecting” the people from something they deem to be evil, but more often, the books simply don’t agree with the agenda of the controlling group. Such was the case with the most famous book burning, which took place under the Nazi regime on May 10, 1933. The May 1933 book burning in Nazi Germany was preceded in nineteenth century Germany. In 1817, German student associations (Burschenschaften) chose the 300th anniversary of Luther’s 95 Theses to hold a festival at the Wartburg, a castle in Thuringia where Luther had sought sanctuary after his excommunication. The students were demonstrating for a unified country. Germany was then a patchwork of states. During the protest, the students burned anti-national and reactionary texts and literature which the students viewed as “Un-German” in nature or content. I wonder if they had any idea that the freedom to protest was the very thing they were looking to take away in the future Germany.

Then, in 1933, Nazi German authorities, decided to synchronize professional and cultural organizations with Nazi ideology and policy (Gleichschaltung). Nazi Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, spearheaded an effort to bring German arts and culture in line with Nazi goals. The government began to remove cultural organizations of Jewish and other officials who were alleged to be politically suspect or who performed or created art works which Nazi ideologues labeled “degenerate.” Goebbels also had a strong ally in the National Socialist German Students’ Association (Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund), so he used them to bring the literary phase into being. German university students were at the forefront of the early Nazi movement, and in the late 1920s. Many of them filled the ranks of various Nazi formations. The ultra-nationalism and antisemitism of middle-class, secular student organizations had been intense and vocal for decades. After World War I, many students opposed the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and found in National Socialism a suitable vehicle for their political discontent and hostility.

On April 6, 1933, the Nazi German Student Association’s Main Office for Press and Propaganda proclaimed a nationwide “Action against the Un-German Spirit,” to end in a literary purge or “cleansing” (Säuberung) by fire. Local chapters were to supply the press with releases and commissioned articles, offer blacklists of “un-German” authors, sponsor well-known Nazi figures to speak at public gatherings, and negotiate for radio broadcast time. Then, in a symbolic act of ominous significance, on May 10, 1933, university students burned upwards of 25,000 volumes of “un-German” books, presaging an era of state censorship and control of culture. On the evening of May 10, in most university towns, right-wing students marched in torchlight parades “against the un-German spirit.” The scripted rituals called for high Nazi officials, professors, university rectors, and university student leaders to address the participants and spectators. In Berlin, some 40,000 persons gathered  in the Opernplatz to hear Joseph Goebbels delivered a fiery address: “No to decadence and moral corruption!” He went on to say, “Yes to decency and morality in family and state! I consign to the flames the writings of Heinrich Mann, Ernst Gläser, Erich Kästner.” Among the authors whose books student leaders burned that night were well-known socialists such as Bertolt Brecht and August Bebel; the founder of the concept of communism, Karl Marx; critical “bourgeois” writers like the Austrian playwright Arthur Schnitzler; and “corrupting foreign influences,” among them American author Ernest Hemingway. I don’t agree with some of these writings, but I also don’t agree with their destruction. People can make up their own minds.

in the Opernplatz to hear Joseph Goebbels delivered a fiery address: “No to decadence and moral corruption!” He went on to say, “Yes to decency and morality in family and state! I consign to the flames the writings of Heinrich Mann, Ernst Gläser, Erich Kästner.” Among the authors whose books student leaders burned that night were well-known socialists such as Bertolt Brecht and August Bebel; the founder of the concept of communism, Karl Marx; critical “bourgeois” writers like the Austrian playwright Arthur Schnitzler; and “corrupting foreign influences,” among them American author Ernest Hemingway. I don’t agree with some of these writings, but I also don’t agree with their destruction. People can make up their own minds.

One of the best ways to form a dictatorship is to suppress knowledge. That’s one reason that propaganda is so important. When the people only hear what the government wants them to, they tend to become compliant…or at least that’s the theory. When Adolf Hitler was elected to office, he was the people’s choice, but they had no idea just how evil he was and how long they would be stuck with him. With the end of democracy, Germany became a one-party dictatorship. The Nazis began a massive propaganda campaign to win the loyalty and cooperation of Germans. The Nazi Propaganda Ministry, directed by Dr Joseph Goebbels, took control of all forms of communication in Germany…newspapers, magazines, books, public meetings, and rallies, art, music, movies, and radio. Viewpoints in any way threatening to Nazi beliefs or to the regime were censored or eliminated from all media. The German people were isolated from the outside world, and while they did not like it, the government became their only source of information.

One of the best ways to form a dictatorship is to suppress knowledge. That’s one reason that propaganda is so important. When the people only hear what the government wants them to, they tend to become compliant…or at least that’s the theory. When Adolf Hitler was elected to office, he was the people’s choice, but they had no idea just how evil he was and how long they would be stuck with him. With the end of democracy, Germany became a one-party dictatorship. The Nazis began a massive propaganda campaign to win the loyalty and cooperation of Germans. The Nazi Propaganda Ministry, directed by Dr Joseph Goebbels, took control of all forms of communication in Germany…newspapers, magazines, books, public meetings, and rallies, art, music, movies, and radio. Viewpoints in any way threatening to Nazi beliefs or to the regime were censored or eliminated from all media. The German people were isolated from the outside world, and while they did not like it, the government became their only source of information.

Germany was now led by a self-educated, high school drop-out named Adolf Hitler, who was by nature strongly anti-intellectual. For Hitler, the reawakening of the long-dormant Germanic spirit, with its racial and militaristic  qualities, was far more important than any traditional notions of learning. Books and writings by such authors as Henri Barbusse, Franz Boas, John Dos Passos, Albert Einstein, Lion Feuchtwanger, Friedrich Förster, Sigmund Freud, John Galsworthy, André Gide, Ernst Glaeser, Maxim Gorki, Werner Hegemann, Ernest Hemingway, Erich Kästner, Helen Keller, Alfred Kerr, Jack London, Emil Ludwig, Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann, Karl Marx, Hugo Preuss, Marcel Proust, Erich Maria Remarque, Walther Rathenau, Margaret Sanger, Arthur Schnitzler, Upton Sinclair, Kurt Tucholsky, Jakob Wassermann, H.G. Wells, Theodor Wolff, Emilé Zola, Arnold Zweig, and Stefan Zweig, were suddenly unGerman. Their books were pulled from libraries and schools. Then, on the night of May 10, 1933, an event unseen in Europe since the Middle Ages occurred as German students from universities once regarded as among the finest in the world, gathered in Berlin to burn books with unGerman ideas. It was the Nazi burning of knowledge. Students can be very impressionable, and easily lead, and these students played right into Hitler’s hand.

qualities, was far more important than any traditional notions of learning. Books and writings by such authors as Henri Barbusse, Franz Boas, John Dos Passos, Albert Einstein, Lion Feuchtwanger, Friedrich Förster, Sigmund Freud, John Galsworthy, André Gide, Ernst Glaeser, Maxim Gorki, Werner Hegemann, Ernest Hemingway, Erich Kästner, Helen Keller, Alfred Kerr, Jack London, Emil Ludwig, Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann, Karl Marx, Hugo Preuss, Marcel Proust, Erich Maria Remarque, Walther Rathenau, Margaret Sanger, Arthur Schnitzler, Upton Sinclair, Kurt Tucholsky, Jakob Wassermann, H.G. Wells, Theodor Wolff, Emilé Zola, Arnold Zweig, and Stefan Zweig, were suddenly unGerman. Their books were pulled from libraries and schools. Then, on the night of May 10, 1933, an event unseen in Europe since the Middle Ages occurred as German students from universities once regarded as among the finest in the world, gathered in Berlin to burn books with unGerman ideas. It was the Nazi burning of knowledge. Students can be very impressionable, and easily lead, and these students played right into Hitler’s hand.

The youth-oriented Nazi movement had always attracted a sizable following among university students. Even back in the 1920s they thought Nazism was the wave of the future. They joined the National Socialist  German Students’ League, put on swastika armbands and harassed anti-Nazi teachers. Many formerly reluctant professors were swept along by the outpouring of student enthusiasm that followed Hitler’s seizure of power. Most of the professors eagerly surrendered their intellectual honesty and took the required Nazi oath of allegiance. They also wanted to curry favor with Nazi Party officials in order to grab one of the academic vacancies resulting from the mass expulsion of Jewish professors and deans. The entire education system of a nation changed…almost overnight. As the German-Jewish poet, Heinrich Heine, had declared, a hundred years before the advent of Hitler, “Wherever books are burned, human beings are destined to be burned too.” And so it was in the end.

German Students’ League, put on swastika armbands and harassed anti-Nazi teachers. Many formerly reluctant professors were swept along by the outpouring of student enthusiasm that followed Hitler’s seizure of power. Most of the professors eagerly surrendered their intellectual honesty and took the required Nazi oath of allegiance. They also wanted to curry favor with Nazi Party officials in order to grab one of the academic vacancies resulting from the mass expulsion of Jewish professors and deans. The entire education system of a nation changed…almost overnight. As the German-Jewish poet, Heinrich Heine, had declared, a hundred years before the advent of Hitler, “Wherever books are burned, human beings are destined to be burned too.” And so it was in the end.