atomic bomb

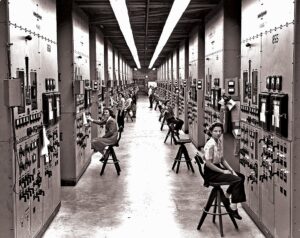

During World War II, a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, joined the Manhattan Project at the Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Known as the Calutron Girls, the group worked for the project from 1943 to 1945. The women were taught to monitor dials and watch meters for calutrons, which are mass spectrometers adapted for separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons for use during World War II. While the women worked at their jobs, and learned how to read the instruments they were required to monitor, they were not allowed to know the purpose of these things.

During World War II, a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, joined the Manhattan Project at the Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Known as the Calutron Girls, the group worked for the project from 1943 to 1945. The women were taught to monitor dials and watch meters for calutrons, which are mass spectrometers adapted for separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons for use during World War II. While the women worked at their jobs, and learned how to read the instruments they were required to monitor, they were not allowed to know the purpose of these things.

They were actually monitoring the manufacturing of enriched uranium that was to be used to make the “Little Boy” atomic bomb for the Hiroshima nuclear bombing to be carried out on August 6, 1945. The Manhattan Project, which was established to develop nuclear weapons, required uranium-235 (U235), the fissionable isotope of uranium. The vast majority of uranium that is mined from the ground is uranium-238. Only about while only 0.7% is U235. The scientists in charge of the project developed several processes for separating the isotopes of uranium, including electromagnetic separation and gaseous diffusion.

“The Y-12 factory was built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to house 1,152 calutrons, a machine used for isotope separation. The word “calutron” is a portmanteau of California University Cyclotron. Calutrons, a variation on mass spectrometers, work by combining uranium with chlorine to make uranium tetrachloride, which is then ionized and put in a vacuum chamber with a magnetic field. When the charged particles move through the magnetic field, they move in a curve, the radius of which is proportional to the mass of the particles. The two isotopes differ in mass by about 1% and can thus be separated.”

The process of separating the U235 Uranium out of the oar was relatively simple, but it still required people to constantly monitor the calutrons. Unfortunately, during World War II, many of the men were fighting. That left a shortage of labor. There simply weren’t enough scientists to operate all of the calutrons. So, the government recruited farm girls to operate the calutrons instead. The main reason for using the young women, was that they were readily available, accustomed to hard work. A stipulation of their employment was that they were not to ask excessive questions, and they had to be loyal and docile. I’m sure these women thought they were doing something top secret and all, but I don’t think they had any idea of the gravity of this project. Lives were on the line, and lives would be lost. Still, they didn’t know that, so I suppose their superiors assumed it would let them sleep at night. I suppose it did. These women honestly didn’t know what they were a part of…some until years later. They would never forget what they did, and they would always wonder if it was right or wrong.

The Tennessee Eastman Company, which ran the Y-12 site, recruited around 10,000 local women between 1943 and 1945. They hired train operators with only a high school education, and they used a large local advertising campaign to recruit workers. One ad read, “When you’re a grandmother you’ll brag about working at Tennessee Eastman.” Word of mouth brought in several other workers. Of course, in hard times, a big motivator was the money being paid. Plus, these women were patriots, and this work was for the war effort. They were trained for three weeks, and they went to work.

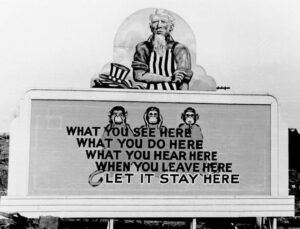

The Tennessee Eastman Company was loyal to the cause. They put a billboard on the premises reading “What you see here / what you do here / what you hear here / when you leave here / let it stay here,” with three wise monkeys to demonstrate “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” Another billboard at the Oak Ridge location,  encouraged secrecy among workers. These companies demanded secrecy and confidentiality…if these women wanted to keep their jobs. According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” Of course, that was correct, but these women would have to live with what they did, once they knew what it was. Testimonies said women who talked about what they were doing disappeared. One young woman who “disappeared” was said to have “died from drinking some poison moonshine.” If they were too nosy about what they were working on, they were replaced. Cars going in and out were searched, and letters were opened and read. This was vital and this was no joke. Anything but secrecy would not be tolerated.

encouraged secrecy among workers. These companies demanded secrecy and confidentiality…if these women wanted to keep their jobs. According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” Of course, that was correct, but these women would have to live with what they did, once they knew what it was. Testimonies said women who talked about what they were doing disappeared. One young woman who “disappeared” was said to have “died from drinking some poison moonshine.” If they were too nosy about what they were working on, they were replaced. Cars going in and out were searched, and letters were opened and read. This was vital and this was no joke. Anything but secrecy would not be tolerated.

The work these women did was not what would be considered labor intensive by any means. The women sat on high stools for 8-hour shifts, seven days per week, “monitoring gauges and adjusting knobs to keep the needles where they were supposed to be and recording readings.” The knobs the women were adjusting were simply labeled with cryptic letters. The women did not know what the letters stood for. What they were taught was that “if you got your M voltage up and your G voltage up, then Product would hit the birdcage in the E box at the top of the unit and if that happened, you’d get the Q and R you wanted.” Okay…whatever that meant. All they knew was that they had to make sure the machine remained at the correct temperature. That was vital and if it got too hot, they used liquid nitrogen to cool it down. If the needles reached a point where they could not control them, they had to call someone else to come help…immediately!!!

Former Calutron Girl Wynona Arrington Butner said, “We all wore little fountain-pen-sized dosimeters. Part of signing out of the plant was to check the amount of radiation that you had absorbed every day.” Civilian workers paid $2.50 per month (single) or $5.00 per month (family) for medical insurance. I don’t know if they understood what radiation could do to them or not, but if they did, they would know that the wages paid and even the insurance help, was probably not enough.

Some Calutron Girls had more of a sense of what they were working on than others. Butner, who had some training in chemistry, said she and others with a similar background had some sense of what they were doing. They knew they were producing “the Product,” and they guessed it was somewhere near the bottom of the periodic table. Willie Baker, on the other hand, said, “Even when somebody let it slip that we were building a bomb, I didn’t know what they meant. I was just a country girl. I had no understanding of what an atomic bomb was.” Later, I’m sure the gravity of the work she did, weighed heavily on Baker.

Over two years, the calutrons at Y-12 had produced about 140 pounds of U235. This was enough to make the first atomic bomb. By December 1945, enough uranium for a second Little Boy was available. Then, it all hit these women, because on August 6, 1945, when the US dropped the first bomb, “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima, Japan, the Calutron Girls were finally told what they had been working on. I can’t imagine how they must have felt. When they heard the news, some women were working, while others were in their dorm rooms. Someone came and told them that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan, and everyone there had played a part in making it. Yes, it was the enemy, and death happens in war. Nevertheless, the Calutron Girls had mixed feelings about their part in the bomb. Ruth Huddleston said she was “really happy at the time, because her boyfriend was stationed in Germany, and this would bring him back.” Still, it bothered her that she had a part in killing so many people, but she accepted that “if the bomb hadn’t been dropped, then probably more people would have been killed. …But even today, if I think too much about it, it bothers me.” Butner had a similar experience, because at the time, she was happy that the war was over and people she knew in the service could come  home, but over time, she began to question whether it was the right thing to do. I think many people over the years have questioned it, but good, bad, or ugly, World War II was over.

home, but over time, she began to question whether it was the right thing to do. I think many people over the years have questioned it, but good, bad, or ugly, World War II was over.

Most of the Calutron Girls are gone now, but those who remain, such as Huddleston, regularly shared their stories with the public, often alongside Oak Ridge historian Ray Smith. The women are the subject of the nonfiction book “The Girls of Atomic City” by Denise Kiernan and the novel “The Atomic City Girls” by Janet Beard. I’m sure that many of these women suffered nightmares over the work they did, but did not know they were doing. While I know they suffered much anxiety over that, I hope they also know that we are so grateful for their service to this great nation.

The world was a crazy place on August 20, 1945. It was just eleven days after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Japan. The world was a little “scary.” Just knowing that entire towns could be blown off the face of the earth in an instant, changed the whole perspective of life as we knew it. The war was almost over. By September 2, 1945, World War II would be a blip in the rearview mirror of history. Maybe it was time to look for something…happy, for a change.

The world was a crazy place on August 20, 1945. It was just eleven days after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Japan. The world was a little “scary.” Just knowing that entire towns could be blown off the face of the earth in an instant, changed the whole perspective of life as we knew it. The war was almost over. By September 2, 1945, World War II would be a blip in the rearview mirror of history. Maybe it was time to look for something…happy, for a change.

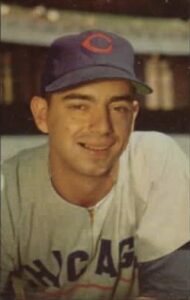

Enter Brooklyn Dodgers utility player, Tommy Brown. He was a local kid, who was born December 6, 1927, in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn. Brown never knew his father and was raised primarily by an aunt and uncle. That was probably the best thing that could have happened. Brown’s upbringing was such that he was able to make something of himself. He started playing baseball, and he was good enough to be called up to the Majors. Brown made his debut with the Dodgers in 1944, when he was just 16 years old. It was an unusual time, because during World War II, millions of men served overseas, so the ball players were serving in the military. Men like future Hall of Famers Ted Williams and Yogi Berra were among them. That left a group of aspiring teenagers in line for the majors in an almost unheard of shot in the big leagues. Fifteen-year-old Joe Nuxhall was also called up and pitched 2/3 of an inning for the Cincinnati Reds in the summer of 1944. It would be almost like they were replacement players.

On August 3, 1944, while playing for the Newport News (Virginia) Builders of the Class B Piedmont League, Brown got the call that changed not only his life, but baseball history forever. He was headed to the majors,  with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Apparently, they had tried Bobby Bragan at shortstop but were looking for someone more mobile. Dodgers’ manager Leo Durocher told Brown that day he would play both games of a doubleheader against the Chicago Cubs. After that shock wore off…for about a second, “Brown, according to a bio on the Society of American Baseball Research web site, advised his manager that he had ridden the train all night, ‘but Leo responded that he didn’t care.'” I guess they were desperate. Brown became the youngest non-pitcher ever to play in a major league game, and the second-youngest overall after Joe Nuxhall, who was 15 years and 316 days old when he first appeared as a pitcher for the Cincinnati Reds on June 10, 1944. He got two hits in eight at-bats as the Cubs beat the Dodgers in both games, 6-2 and 7-1. In 1944, he played a total of 46 games, hitting .164 without a homer. Brown, nicknamed “Buckshot,” threw and batted right-handed. He stood 6 feet 1 inch tall and weighed 170 pounds. Then, on August 20, 1945, he hit a home run…his team’s only run in an 11-1 loss to the Pittsburgh Pirates. He finished that season with a .245 batting average. That home run may not seem like much, but remember that Brown was just 16 years old at the time. With that “homer” to

with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Apparently, they had tried Bobby Bragan at shortstop but were looking for someone more mobile. Dodgers’ manager Leo Durocher told Brown that day he would play both games of a doubleheader against the Chicago Cubs. After that shock wore off…for about a second, “Brown, according to a bio on the Society of American Baseball Research web site, advised his manager that he had ridden the train all night, ‘but Leo responded that he didn’t care.'” I guess they were desperate. Brown became the youngest non-pitcher ever to play in a major league game, and the second-youngest overall after Joe Nuxhall, who was 15 years and 316 days old when he first appeared as a pitcher for the Cincinnati Reds on June 10, 1944. He got two hits in eight at-bats as the Cubs beat the Dodgers in both games, 6-2 and 7-1. In 1944, he played a total of 46 games, hitting .164 without a homer. Brown, nicknamed “Buckshot,” threw and batted right-handed. He stood 6 feet 1 inch tall and weighed 170 pounds. Then, on August 20, 1945, he hit a home run…his team’s only run in an 11-1 loss to the Pittsburgh Pirates. He finished that season with a .245 batting average. That home run may not seem like much, but remember that Brown was just 16 years old at the time. With that “homer” to  his credit, Brown remains the youngest player to homer in a Major League Baseball game, a record that will likely never be broken.

his credit, Brown remains the youngest player to homer in a Major League Baseball game, a record that will likely never be broken.

Brown played seven more seasons in the big leagues, spending time with the Philadelphia Phillies and Cubs after leaving Brooklyn. He never became anything more than a part-time player, but he will always have the distinction of youngest person to homer to his credit. Brown married a woman from Nashville and stayed in that area after his playing career ended. He worked at the Ford Glass Plant for thirty-five years, before retiring in 1993. He continues to live in retirement in Brentwood, Tennessee.

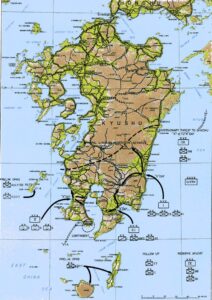

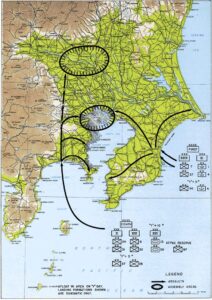

Near what is now known to be the end of World War II, a plan was devised to invade the Japanese home islands. In the end, Operation Downfall was not carried out, because Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet declaration of war, and the invasion of Manchuria. Nevertheless, in the days and months leading up to the planned attack, with its two parts…Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet, the United States Armed Forces ordered 1 million Purple Heart medals, in anticipation of a bloody battle. Operation Olympic was set to begin in November 1945, and was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost

Near what is now known to be the end of World War II, a plan was devised to invade the Japanese home islands. In the end, Operation Downfall was not carried out, because Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet declaration of war, and the invasion of Manchuria. Nevertheless, in the days and months leading up to the planned attack, with its two parts…Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet, the United States Armed Forces ordered 1 million Purple Heart medals, in anticipation of a bloody battle. Operation Olympic was set to begin in November 1945, and was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost  main Japanese island, Kyushu, with the recently captured island of Okinawa to be used as a staging area. The second attack was planned for early 1946. Operation Coronet was supposed to be the invasion of the Kanto Plain, near Tokyo, on the main Japanese island of Honshu. Important airbases on Kyushu that would be captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet. If Downfall had taken place, it would have been the largest amphibious operation in history…even surpassing D-Day.

main Japanese island, Kyushu, with the recently captured island of Okinawa to be used as a staging area. The second attack was planned for early 1946. Operation Coronet was supposed to be the invasion of the Kanto Plain, near Tokyo, on the main Japanese island of Honshu. Important airbases on Kyushu that would be captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet. If Downfall had taken place, it would have been the largest amphibious operation in history…even surpassing D-Day.

This planned set of attacks was no mystery to Japan either, because their geography made this invasion plan quite obvious. The Japanese were able to accurately predict the Allied invasion plans, and they adjusted their defensive plan, known as Operation  Ketsugo, accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyushu, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations. Casualty predictions varied widely, but they were expected to be extremely high. Depending on the degree to which Japanese civilians would have resisted the invasion, estimates ran up into the millions for Allied casualties. No wonder the United States expected to need 1 million Purple Heart medals. Thankfully, those millions of Allied casualties never materialized, because when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the war ended. The United States was left with 1 million Purple Heart medals, which they are still using today. I think that while having 1 million Purple Heart medals isn’t the worst thing ever, just the fact that we still have some of those 1 million Purple Heart medals means that, in some way, we have kept some of our soldiers safe over the years. I don’t know how many are left, but it doesn’t matter, because at this point, 78 years later…there are some left.

Ketsugo, accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyushu, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations. Casualty predictions varied widely, but they were expected to be extremely high. Depending on the degree to which Japanese civilians would have resisted the invasion, estimates ran up into the millions for Allied casualties. No wonder the United States expected to need 1 million Purple Heart medals. Thankfully, those millions of Allied casualties never materialized, because when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the war ended. The United States was left with 1 million Purple Heart medals, which they are still using today. I think that while having 1 million Purple Heart medals isn’t the worst thing ever, just the fact that we still have some of those 1 million Purple Heart medals means that, in some way, we have kept some of our soldiers safe over the years. I don’t know how many are left, but it doesn’t matter, because at this point, 78 years later…there are some left.

Construction began on the White House on October 13, 1792, and was finally finished on November 1, 1800. Construction was slower in those days, because they didn’t have the equipment we have today. The current White House has 132 rooms. The original White House had 100 rooms. The White House has 54,900 square feet. The White House sits on 18 acres of land. It all it is an impressive building, but there is more to it than just that.

Construction began on the White House on October 13, 1792, and was finally finished on November 1, 1800. Construction was slower in those days, because they didn’t have the equipment we have today. The current White House has 132 rooms. The original White House had 100 rooms. The White House has 54,900 square feet. The White House sits on 18 acres of land. It all it is an impressive building, but there is more to it than just that.

There have been a number of rooms that began as one thing, only to become something else later on. One of the rooms that has had a couple of identities is the Press Briefing Room. These days it is the James S. Brady Press Briefing Room. It was so named after White House Press Secretary James Brady, who was shot and permanently disabled during the assassination attempt on President Reagan. That room, located in the West Wing of the White House was not always such a necessary room, mostly because press briefings are really more of a modern-day thing. The room has always existed, however. In 1909, it was the White House laundry, and during President Truman’s time in office (April 12, 1945 – January 20,1953) it was the White House pool.

By 1950, the White House was 150 years old and in a serious state of disrepair. In order to make is inhabitable

again, the entire building was gutted and rebuilt to make it more stable. It also seemed like a good time to improve on its design, so some improvements and additions were made. White House architect Lorenzo Simmons Winslow designed and built an air raid shelter under the East Terrace on the orders of naval aide Rear Admiral Robert Dennison. There had been a bomb shelter before, but it was built in 1942 and with the invention of the atomic bomb, the old shelter was not strong enough to withstand such an assault. Because little research had been conducted into how to withstand such an assault, construction of the shelter took more than two years and required the removal of the East Terrace entirely. Unfortunately, the 1952 shelter was rendered obsolete when the first test produced a force of 10.4 million tons. This shelter was designed to withstand a force of only 30,000 tons, so this would never work.

again, the entire building was gutted and rebuilt to make it more stable. It also seemed like a good time to improve on its design, so some improvements and additions were made. White House architect Lorenzo Simmons Winslow designed and built an air raid shelter under the East Terrace on the orders of naval aide Rear Admiral Robert Dennison. There had been a bomb shelter before, but it was built in 1942 and with the invention of the atomic bomb, the old shelter was not strong enough to withstand such an assault. Because little research had been conducted into how to withstand such an assault, construction of the shelter took more than two years and required the removal of the East Terrace entirely. Unfortunately, the 1952 shelter was rendered obsolete when the first test produced a force of 10.4 million tons. This shelter was designed to withstand a force of only 30,000 tons, so this would never work.

In addition to the new nuclear shelter, a tunnel was added. These days those tunnels are big in the news, but back then, they were probably a little-known addition. This reinforced concrete channel ran from the West Wing to the East Wing. Though not enough to stop a nuclear incident itself, the tunnel allowed quick passage from one end of the White House to the other, as well as access to the new air raid shelter. The presence of the tunnel demonstrates just how concerned the Truman White House was about securing itself against air assaults at that volatile time in history. That first tunnel inside the White House isn’t the only underground feature. In 1987, a second tunnel was built under the name Project ZP. That tunnel, accessible from a secret passage

within the Oval Office, leads to the basement of the East Wing and on to the Treasury Building. Its construction, which was largely secret, created a large sinkhole in the White House rose garden. The tunnel was reportedly built to quickly get the president out of the office during an incursion, but it was also used at least once to sneak former president Richard Nixon into a foreign policy meeting. I’m sure there are other changes to the White House, that we are not privy to, and may never know, because there are always secrets in this kind of building.

within the Oval Office, leads to the basement of the East Wing and on to the Treasury Building. Its construction, which was largely secret, created a large sinkhole in the White House rose garden. The tunnel was reportedly built to quickly get the president out of the office during an incursion, but it was also used at least once to sneak former president Richard Nixon into a foreign policy meeting. I’m sure there are other changes to the White House, that we are not privy to, and may never know, because there are always secrets in this kind of building.

When the first atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the city was instantly in ruins. The bomb immediately ended the lives of 80,000 of the 350,000 people of Hiroshima.

When the first atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the city was instantly in ruins. The bomb immediately ended the lives of 80,000 of the 350,000 people of Hiroshima.

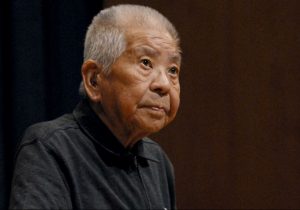

Tsutomu Yamaguchi was born on March 16, 1916 in Nagasaki, Japan, where he grew up and in the 1930s, joined Mitsubishi Heavy Industries working as a draftsman designing oil tankers. Then in the summer of 1945, he was in Hiroshima for a three-month-long business trip. That trip was at its conclusion on August 6th, and he was preparing to leave the city with two colleagues, Akira Iwanaga and Kuniyoshi Sato. They were on their way to the train station when Yamaguchi realized he had forgotten his hanko (a type of identification stamp common in Japan) and returned to his workplace to get it. That one act would have monumental consequences.

At 8:15am, Yamaguchi was walking towards the docks when the American B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped the Little Boy atomic bomb near the center of the city, only 1.9 miles away. Yamaguchi recalls seeing the bomber and two small parachutes, before there was “a great flash in the sky, and I was blown over”. The explosion  ruptured his eardrums, blinded him temporarily, and left him with serious radiation burns over the left side of the top half of his body. After recovering, he crawled to a shelter and, having rested, he set out to find his colleagues. They had also survived and together they spent the night in an air-raid shelter before returning to Nagasaki the following day. In Nagasaki, he received treatment for his wounds and, despite being heavily bandaged, he reported for work on August 9th. As soon as he could get out, Yamaguchi went back home to Nagasaki.

ruptured his eardrums, blinded him temporarily, and left him with serious radiation burns over the left side of the top half of his body. After recovering, he crawled to a shelter and, having rested, he set out to find his colleagues. They had also survived and together they spent the night in an air-raid shelter before returning to Nagasaki the following day. In Nagasaki, he received treatment for his wounds and, despite being heavily bandaged, he reported for work on August 9th. As soon as he could get out, Yamaguchi went back home to Nagasaki.

Ironically, Yamaguchi arrived in Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. Back at his office, Yamaguchi was describing the blast in Hiroshima to his supervisor at 11:00am, when the American bomber Bockscar dropped the Fat Man atomic bomb over the city. Yamaguchi’s workplace again put him 1.9 miles from ground zero. This time he was unhurt by the explosion, however, he was unable to replace his now ruined bandages and he suffered from a high fever and continuous vomiting for over a week. I’m sure he felt like he was dying. Technically, some 100 people were known to have been  affected by both bombings. In 1957, Yamaguchi was recognized as a hibakusha “explosion-affected person” of the Nagasaki bombing. It is unknown, why the government didn’t recognize the other survivors. In 2006 Yamaguchi addressed the United Nations General Assembly in New York City in support of nuclear disarmament. It was not until March 24, 2009, that the government of Japan officially recognized his presence in Hiroshima three days earlier, as well. He died of stomach cancer on January 4, 2010, at the age of 93. Yamaguchi was the only “officially” documented survivor of both the August 6, 1945 Hiroshima and the August 9, 1945 Nagasaki atomic bombings during World War II.

affected by both bombings. In 1957, Yamaguchi was recognized as a hibakusha “explosion-affected person” of the Nagasaki bombing. It is unknown, why the government didn’t recognize the other survivors. In 2006 Yamaguchi addressed the United Nations General Assembly in New York City in support of nuclear disarmament. It was not until March 24, 2009, that the government of Japan officially recognized his presence in Hiroshima three days earlier, as well. He died of stomach cancer on January 4, 2010, at the age of 93. Yamaguchi was the only “officially” documented survivor of both the August 6, 1945 Hiroshima and the August 9, 1945 Nagasaki atomic bombings during World War II.

There have always been wars, and wars include bombs of some kind. It is a fact that everyone seems to understand, and to a degree accept. I suppose they look at it as collateral damage, but the reality is that it is people, property, homes, and businesses. Sometimes I wonder if mankind will ever get to a point where collateral damage is too much to pay. Of course, that will not happen. War means death and destruction, and there will be wars as long as time endures.

There have always been wars, and wars include bombs of some kind. It is a fact that everyone seems to understand, and to a degree accept. I suppose they look at it as collateral damage, but the reality is that it is people, property, homes, and businesses. Sometimes I wonder if mankind will ever get to a point where collateral damage is too much to pay. Of course, that will not happen. War means death and destruction, and there will be wars as long as time endures.

The fact is that no sane human being likes the collateral damage that war brings, but there are, unfortunately, many insane heads of states. These people kill thousands of their own people for almost no reason. They simply disagree, or they look different, or they have a different religion, and that means they must die. So, war begins, and more people die to try to free the people who have been oppressed by their hateful dictators.

World War II took in the Axis of Evil nations and the Allies, who were fighting against regimes like the Nazis, and Japanese. Both were terrible, and neither wanted to give up. Finally, when it was decided that Japan had to be stopped at all costs, the United States made the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, on August 6, 1945, and on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians. It was another in a long list of bombing events of World War II and many other wars. It was all the same old story, right? Wrong.

The two Atomic Bombs dropped, changed the world. They were both the first, and the last times Atomic Bombs were dropped in war. It was as if the world finally saw what these bombs did to people. It was as if they finally felt sick to their stomach…both sides!! During the Cold War, there were a couple of times when the United States and the Soviet Union came close to using the Atomic Bomb, but they decided that they just couldn’t do it. That said, they decided that there really was a line that should never be crossed. Since 1945, and the dropping of two of the most devastating bombs ever, mankind has finally decided that we should not go there again, thankfully.

World War II had dragged on for almost six years, when the United States took things to the next, and as it turns out, final level. For quite some time, Japan had been one of the forces to be reckoned with. Now, with so much new technology, a plan has begun to form to put an end to this war, once and for all. The Japanese had no idea what was coming…how the 6th of August, 1945 would change things forever.

World War II had dragged on for almost six years, when the United States took things to the next, and as it turns out, final level. For quite some time, Japan had been one of the forces to be reckoned with. Now, with so much new technology, a plan has begun to form to put an end to this war, once and for all. The Japanese had no idea what was coming…how the 6th of August, 1945 would change things forever.

That August 6th in 1945 dawned like any other day, but at it’s end, the world would find that everything had changed. The power to destroy whole cities in an instant was in our hands. At 8:16am, an American B-29 bomber dropped the world’s first deployed atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The ensuing explosion wiped out 90 percent of the city and immediately killed 80,000 people. Tens of thousands more would later die of radiation exposure. Three days later, on August 9, 1945, a second B-29 dropped another  A-bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people. With these two events, it was very clear that the nations had the ability to bring mass destruction. Hopefully, they would also have the compassion, not to do it.

A-bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people. With these two events, it was very clear that the nations had the ability to bring mass destruction. Hopefully, they would also have the compassion, not to do it.

With such a show of power, Japan’s Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s unconditional surrender to the Japanese people in World War II in a radio address on August 14th, citing the devastating power of “a new and most cruel bomb” as the reason Japan could no longer stand against the Allies. I’m sure the war-ravaged people of Japan were almost relieved. Of course, that meant that they did not know what their future would bring, but the recent past hadn’t been so great either, so they didn’t have too much to lose really.

Japan’s War Council, urged by Emperor Hirohito, submitted a formal declaration of surrender to the Allies, on August 10, but the fighting continued between the Japanese and the Soviets in Manchuria and between the Japanese and the United States in the South Pacific. During that time, a Japanese submarine attacked the Oak Hill, an American landing ship, and the Thomas F. Nickel, an American destroyer, both east of Okinawa. On August 14, when Japanese radio announced that an Imperial Proclamation was coming soon, in which Japan would accept the terms of unconditional surrender drawn up at the Potsdam Conference. The news did not go over well. More than 1,000 Japanese soldiers stormed the Imperial Palace in an attempt to find the

proclamation and prevent its being transmitted to the Allies. Soldiers still loyal to Emperor Hirohito held off the attackers. That evening, General Anami, the member of the War Council most adamant against surrender, committed suicide. His reason was to atone for the Japanese army’s defeat, and he refused to hear his emperor speak the words of surrender. I guess the surrender was not a relief to everyone.

proclamation and prevent its being transmitted to the Allies. Soldiers still loyal to Emperor Hirohito held off the attackers. That evening, General Anami, the member of the War Council most adamant against surrender, committed suicide. His reason was to atone for the Japanese army’s defeat, and he refused to hear his emperor speak the words of surrender. I guess the surrender was not a relief to everyone.

When I think of people disappearing, my Christian mind automatically envisions the rapture of the church, but there have, of course, been other times when people have disappeared, and some of them were utterly horrifying. One such horrifying version of people disappearing is the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I have never been able to wrap my head around my feelings about the Atomic Bombs that were dropped on August 6 and August 9, 1945, respectively. Though we were at war, the Atomic Bomb seemed such an extreme weapon. Nevertheless, it was what was used those days to show that we meant business.

When I think of people disappearing, my Christian mind automatically envisions the rapture of the church, but there have, of course, been other times when people have disappeared, and some of them were utterly horrifying. One such horrifying version of people disappearing is the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I have never been able to wrap my head around my feelings about the Atomic Bombs that were dropped on August 6 and August 9, 1945, respectively. Though we were at war, the Atomic Bomb seemed such an extreme weapon. Nevertheless, it was what was used those days to show that we meant business.

On August 6th, one of its B-29s dropped a Little Boy uranium gun-type bomb on Hiroshima. Three days later, on August 9th, a Fat Man plutonium implosion-type bomb was dropped by another B-29 on Nagasaki. The bombs immediately devastated their targets. Over the next two to four months, the acute effects of the atomic bombings killed 90,000–146,000 people in Hiroshima and 39,000–80,000 people in Nagasaki…roughly half of the deaths in each city occurred on the first day. Large numbers of people continued to die from the effects of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, compounded by illness and malnutrition, for many months afterward. In both cities, most of the dead were civilians, although Hiroshima had a sizable military garrison. While the bombings were met with mixed feelings worldwide, the plan worked. Just six days later, on August 15, 1945, Japan announced its surrender.

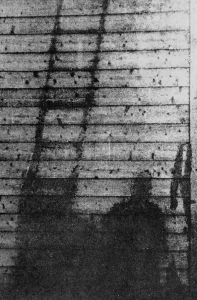

The atomic bombs were successful, but as I said, my feelings were similar to the rest of the world’s feelings. The devastation from the bombs was unbelievable. Those who survived the initial attack died a slow death, and in reality that was the worse way to go. Those who were killed instantly, were in reality obliterated…they simply disappeared. As shocking as that was to me, what I found even more shocking was what was left behind. The atomic bombs basically burned a picture of the victims onto whatever was near them…a wall, stairs, or the side of a building. That was difficult to wrap my head around. When I saw a nuclear shadow of a child playing jump rope that was flashed against the side of a building, my thoughts immediately went to the fact that this child had no idea that his life was about to be over. I don’t suppose there was time for him to feel any pain, and that was probably the most merciful part of the entire horrible event.

The nuclear shadows were everywhere, preserved as vivid reminders of what had taken place. For as long as ten years, the shadows were still there. Then they started to fade. As buildings were remodeled, some of the shadows were removed at preserved in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. One shadow, thought to be the outline of a person who was sitting at the entrance of Hiroshima Branch of Sumitomo Bank when the atomic bomb was dropped over Hiroshima, is known as Human Shadow of Death. According to the museum, “it is thought that the person had been sitting on the stone step waiting for the bank to open when the heat from the bomb burned the surrounding stone white and left their shadow. A black deposit was also found on the shadow.  A piece of stone containing the artifact was cut from the original location and moved to the museum.” Also, according to museum staff, “many visitors to the museum believe that the shadow is the outline of a human vaporized immediately after the bombing. However, the possibility of human vaporization is not supported from a medical perspective. The ground surface temperature is thought to have ranged from 3,000 to 4,000 degrees Celsius just after the bombing. Exposing a body to this level of radiant heat would leave bones and carbonized organs behind. While radiation could severely inflame and ulcerate the skin, complete vaporization of the body is impossible.” Nevertheless, it appears to have happened, whether they believe it or not.

A piece of stone containing the artifact was cut from the original location and moved to the museum.” Also, according to museum staff, “many visitors to the museum believe that the shadow is the outline of a human vaporized immediately after the bombing. However, the possibility of human vaporization is not supported from a medical perspective. The ground surface temperature is thought to have ranged from 3,000 to 4,000 degrees Celsius just after the bombing. Exposing a body to this level of radiant heat would leave bones and carbonized organs behind. While radiation could severely inflame and ulcerate the skin, complete vaporization of the body is impossible.” Nevertheless, it appears to have happened, whether they believe it or not.

When most of us think about April Fool’s Day, we think of playing some funny prank on our family or friends, but on April Fool’s Day 1946, the Earth played a prank, if it could be called that, on Hawaii. It was a prank that wasn’t funny, and it would claim the lives of 159 people. Early in the morning of that April Fool’s Day, a 7.4 magnitude earthquake struck in the North Pacific, 13,000 feet beneath the ocean surface, and off Unimak Island in the Aleutian chain, that makes up the tail of Alaska. The quake triggered devastating tidal waves throughout the Pacific, and particularly aimed at Hawaii. The first tidal wave hit Unimak Island shortly after the quake struck. The wave was estimated to be almost 100 feet, and it crashed into a lighthouse 30 feet above sea level. Five people lived in the lighthouse. It was smashed to pieces, and all five were killed instantly. The wave then headed toward the Southern Pacific at 500 miles per hour. The situation was like a freight train carrying an atomic bomb.

When most of us think about April Fool’s Day, we think of playing some funny prank on our family or friends, but on April Fool’s Day 1946, the Earth played a prank, if it could be called that, on Hawaii. It was a prank that wasn’t funny, and it would claim the lives of 159 people. Early in the morning of that April Fool’s Day, a 7.4 magnitude earthquake struck in the North Pacific, 13,000 feet beneath the ocean surface, and off Unimak Island in the Aleutian chain, that makes up the tail of Alaska. The quake triggered devastating tidal waves throughout the Pacific, and particularly aimed at Hawaii. The first tidal wave hit Unimak Island shortly after the quake struck. The wave was estimated to be almost 100 feet, and it crashed into a lighthouse 30 feet above sea level. Five people lived in the lighthouse. It was smashed to pieces, and all five were killed instantly. The wave then headed toward the Southern Pacific at 500 miles per hour. The situation was like a freight train carrying an atomic bomb.

Hawaii was 2,400 miles south of the quake’s epicenter, and Captain Wickland of the United States Navy was the first person to spot the coming wave at about 7:00am, four and a half hours after the quake struck in the Aleutian Islands. His position on the bridge of a ship, 46 feet above sea level, put him at eye level with a “monster wave” that he described as two miles long. The first wave came in and receded, then the water in Hilo Bay seemed to disappear. The boats that were docked there, settled on the sea floor, surrounded by flopping fish. Then…the second wave hit…and it was massive!! The city of Hilo was hit by a 32 foot wave that devastated the town. Nearly a third of the city was completely destroyed. The bridge that crossed the Wailuku River was picked up by the wave, and pushed 300 feet away. In Hilo, 96 people lost their lives in the tsunami. Other parts of Hawaii were hit even worse. In some places, the waves reached heights of 60 feet. A schoolhouse in Laupahoehoe was crushed by the tsunami, killing the teacher and 25 students inside.

The massive wave was seen as far away as Chile, where, 18 hours after the quake near Alaska, unusually large waves crashed ashore, but there were no casualties. This tsunami prompted the United States to establish the Seismic SeaWave Warning System two years later, which is now known as the Pacific Tsunami Warning System.

It uses undersea buoys throughout the ocean, in combination with seismic-activity detectors, to find possible killer waves. The warning system was used for the first time on November 4, 1952. That day, an evacuation was successfully carried out, but the expected wave never materialized. Still, like the fire drills we all know about from school, maybe Tsunami Drills wouldn’t be a bad thing either, especially if it would prevent the kind of loss of life that Hawaii experienced on that awful April Fool’s Day in 1946.

It uses undersea buoys throughout the ocean, in combination with seismic-activity detectors, to find possible killer waves. The warning system was used for the first time on November 4, 1952. That day, an evacuation was successfully carried out, but the expected wave never materialized. Still, like the fire drills we all know about from school, maybe Tsunami Drills wouldn’t be a bad thing either, especially if it would prevent the kind of loss of life that Hawaii experienced on that awful April Fool’s Day in 1946.

World War II had dragged on long enough. The Axis of Evil nations didn’t seem to care how many of their own people were killed, as long as victory was theirs…typical of any evil nation. It was time to put a stop to this, and the United States, along with the Allied Nations, could see no other solution to the problem, other than fighting fire with fire…literally. This would be the beginning of a horrible new kind of warfare. I’m sure they didn’t come to that decision lightly. While the Japanese were our enemies, the civilian people didn’t really have much say in what they did. Nevertheless, in a war, sometimes civilians are killed. Collateral damage, they call it. It’s a term for deaths, injuries, or other damage inflicted on an unintended target. In American military terminology, it is used for the incidental killing or wounding of non-combatants or damage to non-combatant property during an attack on a legitimate military target. Knowing that the loss of civilian lives is considered “acceptable” in a war, doesn’t make it easy to live with.

World War II had dragged on long enough. The Axis of Evil nations didn’t seem to care how many of their own people were killed, as long as victory was theirs…typical of any evil nation. It was time to put a stop to this, and the United States, along with the Allied Nations, could see no other solution to the problem, other than fighting fire with fire…literally. This would be the beginning of a horrible new kind of warfare. I’m sure they didn’t come to that decision lightly. While the Japanese were our enemies, the civilian people didn’t really have much say in what they did. Nevertheless, in a war, sometimes civilians are killed. Collateral damage, they call it. It’s a term for deaths, injuries, or other damage inflicted on an unintended target. In American military terminology, it is used for the incidental killing or wounding of non-combatants or damage to non-combatant property during an attack on a legitimate military target. Knowing that the loss of civilian lives is considered “acceptable” in a war, doesn’t make it easy to live with.

The prospect was sickening, but something had to be done. So, on March 10, 1945, 300 American bombers  continue to drop almost 2,000 tons of incendiaries on Tokyo, Japan, in a mission that had begun the previous day. The attack destroyed large portions of the Japanese capital and killed 100,000 civilians. Early in the morning on March 10th, the B-29s dropped their bombs of napalm and magnesium incendiaries over the packed residential districts along the Sumida River in eastern Tokyo. The resulting inferno quickly engulfed Tokyo’s wooden residential structures, and the subsequent firestorm replaced oxygen with lethal gases, superheated the atmosphere, and caused hurricane-like winds that blew a wall of fire across the city. The majority of the 100,000 who perished died from carbon monoxide poisoning and the sudden lack of oxygen, but others died horrible deaths within the firestorm, such as those who attempted to find protection in the Sumida River and were boiled alive, or those who were trampled to death in the rush to escape the burning city. As a result of the attack, 10 square miles of eastern Tokyo were entirely obliterated, and an estimated 250,000 buildings were destroyed. When I think about the loss of life brought on by a complete lack of the Japanese government to surrender when they should have.

continue to drop almost 2,000 tons of incendiaries on Tokyo, Japan, in a mission that had begun the previous day. The attack destroyed large portions of the Japanese capital and killed 100,000 civilians. Early in the morning on March 10th, the B-29s dropped their bombs of napalm and magnesium incendiaries over the packed residential districts along the Sumida River in eastern Tokyo. The resulting inferno quickly engulfed Tokyo’s wooden residential structures, and the subsequent firestorm replaced oxygen with lethal gases, superheated the atmosphere, and caused hurricane-like winds that blew a wall of fire across the city. The majority of the 100,000 who perished died from carbon monoxide poisoning and the sudden lack of oxygen, but others died horrible deaths within the firestorm, such as those who attempted to find protection in the Sumida River and were boiled alive, or those who were trampled to death in the rush to escape the burning city. As a result of the attack, 10 square miles of eastern Tokyo were entirely obliterated, and an estimated 250,000 buildings were destroyed. When I think about the loss of life brought on by a complete lack of the Japanese government to surrender when they should have.

This type of bombing was known as area bombing, and was designed to break Japanese morale and force a surrender. I would imagine that morale was seriously broken after such devastating loss of life and property. The firebombing of Tokyo was the first major firebombing operation of this kind against Japan. Over the next nine days, United States bombers flew similar missions against Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe. Then in August, United States atomic attacks against Hiroshima and Nagasaki finally forced the Japanese surrender. It was an ugly way to have for fight a war, but the Japanese did not seem to care if their own citizens were sacrificed for their evil cause. All they cared about was winning. Thankfully, they didn’t do that either.