allied forces

In the final years of World War II, both the Allied and Axis Powers knew that there was no chance of defeating Hitler without cracking his grasp on Western Europe, and both sides knew that Northern France was the obvious target for an amphibious assault. Hitler’s army seemed to be everywhere. That said, the Allied forces knew they had to come up with a way to “fool” the leader of the Third Reich. Hitler arrogantly thought that he knew what the Allied forces were planning, and that was the best way to create his downfall. The German high command assumed the Allies would cross from England to France at the narrowest part of the channel and land at Pas-de-Calais. The Allies used that to their advantage and decided on the beaches of Normandy…some 200 miles to the west. The beaches of Normandy could be taken as they were, but if the Germans added to their defense by moving their reserve infantry and panzers to Normandy from their garrison in the Pas-de-Calais region, the invasion would be a disaster.

In the final years of World War II, both the Allied and Axis Powers knew that there was no chance of defeating Hitler without cracking his grasp on Western Europe, and both sides knew that Northern France was the obvious target for an amphibious assault. Hitler’s army seemed to be everywhere. That said, the Allied forces knew they had to come up with a way to “fool” the leader of the Third Reich. Hitler arrogantly thought that he knew what the Allied forces were planning, and that was the best way to create his downfall. The German high command assumed the Allies would cross from England to France at the narrowest part of the channel and land at Pas-de-Calais. The Allies used that to their advantage and decided on the beaches of Normandy…some 200 miles to the west. The beaches of Normandy could be taken as they were, but if the Germans added to their defense by moving their reserve infantry and panzers to Normandy from their garrison in the Pas-de-Calais region, the invasion would be a disaster.

In what would become an ingenious plan, the Allied intelligence services created two fake armies to keep the Germans on their toes. One would wonder how they proposed to pull that off. The Allies created two “Ghost Armies.” One would be based in Scotland to create a supposed invasion of Norway and the other headquartered  in southeast England to threaten the Pas-de-Calais. While the operation in Scotland relied mainly on fake radio traffic and the feeding of false information to double agents to create the impression of a substantial army, the southern “Ghost Army” had to seem much more real. The fortitude South was well within the range of prying German ears and eyes, so fake chatter alone would be uncovered too quickly. It had to look and sound like a substantial army was building up in southeast England. They needed boots on the ground there, without actually using too much of their precious manpower. That seems like a monumental task.

in southeast England to threaten the Pas-de-Calais. While the operation in Scotland relied mainly on fake radio traffic and the feeding of false information to double agents to create the impression of a substantial army, the southern “Ghost Army” had to seem much more real. The fortitude South was well within the range of prying German ears and eyes, so fake chatter alone would be uncovered too quickly. It had to look and sound like a substantial army was building up in southeast England. They needed boots on the ground there, without actually using too much of their precious manpower. That seems like a monumental task.

Enter George and his imaginary men. Patton was put in charge of leading a fake army, commonly known as the “Ghost Army” as part of a massive counterintelligence operation preceding D-Day. The “Ghost Army” was an army of inflatable tanks, rubber airplanes, and fake radio signals designed to trick the German army. The mission was insanely successful. The “Ghost Army” was a United States Army tactical deception unit used during World War II officially known as the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops. The 1100-man unit was given a  unique mission within the Allied Army. Their orders…impersonate other Allied Army units to deceive the enemy. It was simple, but it wouldn’t be easy.

unique mission within the Allied Army. Their orders…impersonate other Allied Army units to deceive the enemy. It was simple, but it wouldn’t be easy.

By the evening of June 6, 1944, in what would become known as D-Day, the First Army landed at Normandy. The battle was on, and without the extra troops Hitler might have sent if he wasn’t misled so completely. By June 23, 1945, the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops was on its way home after having served with four US armies through England, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, Holland, and Germany. During their tenure, they put on what many would call a “traveling road show” utilizing inflatable tanks, sound trucks, fake radio transmissions, scripts, and pretense. They staged more than 20 battlefield deceptions, often operating very close to the front lines. While their missions and their work were amazing, their story was kept secret for more than 40 years after the war, until it was declassified in 1996.

As Hitler continued his reign of terror over the people of Germany, in his quest to rule the world, he decided that he needed to destroy much of the German infrastructure so that the Allied forces couldn’t use it as they penetrated deep withing the borders of Germany. Hitler must have known by now that he was losing this war, even in his crazed state, so he was trying to find a way to turn the tide.

As Hitler continued his reign of terror over the people of Germany, in his quest to rule the world, he decided that he needed to destroy much of the German infrastructure so that the Allied forces couldn’t use it as they penetrated deep withing the borders of Germany. Hitler must have known by now that he was losing this war, even in his crazed state, so he was trying to find a way to turn the tide.

The Nero Decree (German: Nerobefehl) was the order issued by Hitler on March 19, 1945, right after the Allies captured the final bridge on the Rhine River that allowed access into Germany. The Nero Decree ordered the destruction of large numbers of bridges in Germany. The official name was Decree Concerning Demolitions in the Reich Territory (Befehl betreffend Zerstörungsmaßnahmen im Reichsgebiet), but that is rather a long name, so it became known as the Nero Decree, after the Roman Emperor Nero, who, according to an apocryphal story, “engineered the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD.”

This act would have wiped out all of Germany’s industry and infrastructure just to keep it from falling under Allied control. Hitler didn’t care about that or about the people who would be affected. The actual task of carrying out such destruction fell to Germany’s armaments minister…and Hitler’s friend, Albert Speer. Speer knew that to follow the order would have a ruinous effect on the German people, so like Von Choltitz, who had disobeyed the order to burn Paris, Speer deliberately disobeyed the order of his friend, who he suspected was mentally unstable. In addition, Speer also issued encrypted alternate orders to delay the destruction. In the end, the Nero Decree wasn’t carried out at all, something which I’m quite certain drove Hitler totally insane.

Speer was one of the highest-ranking members of German leadership to survive the war. He attempted to promote himself as someone who stood up to Hitler. While history does credit him with refusing to follow the Nero Decree, it did not completely exonerate him. Speer was an architect, and he wanted to preserve many buildings he had designed. Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer, born March 19, 1905, in Mannheim, into an upper-middle-class family. He was the second of three sons of Luise Máthilde Wilhelmine (Hommel) and Albert Friedrich Speer. He was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. He was also a close ally of Adolf Hitler, a relationship which would cause him to be convicted at the Nuremberg trials and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Speer returned to London in 1981 to participate in the BBC Newsnight program. He suffered a stroke and died in London on September 1, 1981.

Through the years, Russia, also known as the Soviet Union and the USSR, has been sometimes ally and sometimes enemy of the United States. World War I and World War II found the Soviet Union once again on the side of good as a part of the Allied Forces. The main countries in the Allied powers of World War I were France, the British Empire and the Russian Empire. The main Allied powers of World War II were France, Great Britain, the United States, China, and the Soviet Union. So in these two wars anyway, the United States and Russia were on the same side. The three principal partners in the Axis alliance in World War II were Germany, Italy, and Japan. They were joined by Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and Thailand, who also signed the Tri-Partite Pact as member states.

Through the years, Russia, also known as the Soviet Union and the USSR, has been sometimes ally and sometimes enemy of the United States. World War I and World War II found the Soviet Union once again on the side of good as a part of the Allied Forces. The main countries in the Allied powers of World War I were France, the British Empire and the Russian Empire. The main Allied powers of World War II were France, Great Britain, the United States, China, and the Soviet Union. So in these two wars anyway, the United States and Russia were on the same side. The three principal partners in the Axis alliance in World War II were Germany, Italy, and Japan. They were joined by Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and Thailand, who also signed the Tri-Partite Pact as member states.

On May 12, 1942, Soviet forces under the command of Marshal Semyon Timoshenko attacked the German 6th  Army from a vulnerable point established during the winter counter-offensive. After a promising start, the offensive was stopped on May 15th by massive airstrikes. There were a number of critical Soviet errors by several staff officers and by Joseph Stalin, who failed to accurately estimate the 6th Army’s potential and overestimated their own newly raised forces, facilitated a German pincer attack on May 17th which cut off three Soviet field armies from the rest of the front by May 22nd. The Soviet Army was hemmed into a narrow area, and the 250,000-strong Soviet force inside the pocket was exterminated from all sides by German armored, artillery, and machine gun firepower, as well as 7,700 tons of air-dropped bombs. After six days of encirclement by the German Army, the Soviet resistance ended as their troops were killed or taken prisoner. It was a devastating loss for the Soviets.

Army from a vulnerable point established during the winter counter-offensive. After a promising start, the offensive was stopped on May 15th by massive airstrikes. There were a number of critical Soviet errors by several staff officers and by Joseph Stalin, who failed to accurately estimate the 6th Army’s potential and overestimated their own newly raised forces, facilitated a German pincer attack on May 17th which cut off three Soviet field armies from the rest of the front by May 22nd. The Soviet Army was hemmed into a narrow area, and the 250,000-strong Soviet force inside the pocket was exterminated from all sides by German armored, artillery, and machine gun firepower, as well as 7,700 tons of air-dropped bombs. After six days of encirclement by the German Army, the Soviet resistance ended as their troops were killed or taken prisoner. It was a devastating loss for the Soviets.

The Counter-offensive of the Second Battle of Kharkov, was called Operation Fredericus, and was launched by the Axis forces in the region around Kharkov against the Red Army Izium bridgehead offensive, and was conducted from May 12 to May 28, 1942, on the Eastern Front during World War II. The objective was to  eliminate the Izium bridgehead over Seversky Donets, also known as the “Barvenkovo bulge,” which was one of the Soviet offensive’s staging areas. A winter counter-offensive drove German troops away from Moscow, but depleted the Red Army’s reserves. The Kharkov offensive was next Soviet attempt to expand their strategic initiative, although it failed to secure a significant element of surprise. The battle ended up being an overwhelming German victory, with 280,000 Soviet casualties compared to just 20,000 for the Germans and their allies. The German Army Group South pressed its advantage, encircling the Soviet 28th Army on June 13 in Operation Wilhelm and pushing back the 38th and 9th Armies on June 22.

eliminate the Izium bridgehead over Seversky Donets, also known as the “Barvenkovo bulge,” which was one of the Soviet offensive’s staging areas. A winter counter-offensive drove German troops away from Moscow, but depleted the Red Army’s reserves. The Kharkov offensive was next Soviet attempt to expand their strategic initiative, although it failed to secure a significant element of surprise. The battle ended up being an overwhelming German victory, with 280,000 Soviet casualties compared to just 20,000 for the Germans and their allies. The German Army Group South pressed its advantage, encircling the Soviet 28th Army on June 13 in Operation Wilhelm and pushing back the 38th and 9th Armies on June 22.

Just imagine living in a place where owning or even borrowing a book could get you, and anyone who gave you a book, killed. During the Holocaust, the Jews and other nationalities and religious groups who didn’t fit in with the Aryan race, were considered non-people, and therefore expendable. They were not allowed to live like normal people. They were considered “expendable.” Their lives were not worth the trouble it took to care for them, even their fiends and neighbors were expected to turn them over to be deported to the ghettos and even killed. They were often powerless to help themselves. Still, most of them never lost hope. When the Nazis began to occupy Czechoslovakia in 1939, the persecution of the Jews began almost immediately. Things were hard for everyone, but the children were often in more peril than anyone else. Many were to young to work and that made them even less “important” to the Nazis. To make matters worse, they were often separated from their parents…everything they knew was stripped from them.

Just imagine living in a place where owning or even borrowing a book could get you, and anyone who gave you a book, killed. During the Holocaust, the Jews and other nationalities and religious groups who didn’t fit in with the Aryan race, were considered non-people, and therefore expendable. They were not allowed to live like normal people. They were considered “expendable.” Their lives were not worth the trouble it took to care for them, even their fiends and neighbors were expected to turn them over to be deported to the ghettos and even killed. They were often powerless to help themselves. Still, most of them never lost hope. When the Nazis began to occupy Czechoslovakia in 1939, the persecution of the Jews began almost immediately. Things were hard for everyone, but the children were often in more peril than anyone else. Many were to young to work and that made them even less “important” to the Nazis. To make matters worse, they were often separated from their parents…everything they knew was stripped from them.

In 1942, when a girl named Dita Polachova was 13 years old, she and her parents were deported to Ghetto Theresienstadt life got even worse than it was before. Later they were sent to Auschwitz, where Dita’s father died. She and her mother were sent to forced labor in Germany and finally to a concentration camp called Bergen-Belsen. Dita’s mother died at Bergen-Belsen. Even in the face of so much sadness in her life, Dita never gave up. She risked her own life to protect a selection of eight books smuggled in by prisoners of Auschwitz. She stored the books in hidden pockets in her smock, and circulated them to the hundreds of children imprisoned in Block 31. Books were forbidden for the prisoners in the camps. The Nazis didn’t want them to have any knowledge of the outside world, or access to any kind of education materials or any books. The Nazis believed that none of these people were going to survive their stay in the camps anyway, so they didn’t need to do anything but work and die.

The prisoners had different ideas. Within the walls, there was a family camp known as BIIb. It was a place where the children could play and sing, but school was prohibited. Nevertheless, the Nazis were not able to enforce their will on the people. In spite of the orders of the Nazis, Fredy Hirsch established a small, yet influential school to house the children while their parents slaved in the camp. The materials were the biggest problem. The books, had to be hidden from the Nazi guards at all costs. Hirsch selected Dita, a brave and independent young woman from Prague to take over as the new Librarian of Auschwitz in January of 1944. Dita was a brave girl, who took her responsibility seriously.

While her parents are trying to stay alive in Auschwitz, Dita was fighting her own battle to preserve the books that bring joy to the children in the camp. The books are one of the few things that allow the children to escape from the walls in which they are surrounded, even if just for a moment. As the war progresses, Dita continues to diligently serve the teachers and children of Block 31. Then, Dita’s situation grew much worse. Her father passed away in the camp due to pneumonia. Dita and her mother are left alone to fight the battle on their own. Dita’s mother is grew weaker with age, and Dita knew she had to assume more responsibility. Dita is aware of the fact that the camp is simply a front to produce Nazi propaganda. She began to fight despair, as she struggles to feel the value in her life. By March 1944, the feeling of hopelessness grows. The Nazis announce that the inmates who arrived in September will be transferred to another division, which is really code for  murder. The BIIb continued until they heard that the Nazis are going to liquidate the family camp and separate the fit to work from the rest. Dita’s mother Liesl, was grown old and very weak by now. She was able to sneak into the group that is fit to work along with her daughter, narrowly. They were sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Just when Dita gets to the point where she feels this might be the end, the Allied forces liberate the camp, but it is too late for Dita’s mother, who died just after the English arrived. Dita is now free, but it has been at great cost…the kind most of us cannot begin to comprehend. Dita later met and married Otto Kraus, an author, and they settled in Israel where they were both teachers.

murder. The BIIb continued until they heard that the Nazis are going to liquidate the family camp and separate the fit to work from the rest. Dita’s mother Liesl, was grown old and very weak by now. She was able to sneak into the group that is fit to work along with her daughter, narrowly. They were sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Just when Dita gets to the point where she feels this might be the end, the Allied forces liberate the camp, but it is too late for Dita’s mother, who died just after the English arrived. Dita is now free, but it has been at great cost…the kind most of us cannot begin to comprehend. Dita later met and married Otto Kraus, an author, and they settled in Israel where they were both teachers.

In the midst of World War II, February 1942, to be more exact, the Japanese fleet gave the combined Dutch-American-Australian-British fleet a beating that almost wiped them out completely, during the Battle of the Java Sea. The defeat brought about the Japanese occupation of the entire Netherlands East Indies. After the battle ended, only four Dutch warships were left in the Dutch East Indies. They knew there was no way they would be able to take down the Japanese fleet by themselves, so they decided to try to escape to Australia. The failed attempt left three of the four ships sunk, and one in hiding. The problem they had, was that the seas were full of warships and the skies were swarming with Japanese planes. It was going to be virtually impossible to sail the 1,000 miles of ocean to safety. The HNLMS Abraham Crijnssen, which was the last ship, had a big problem, for which they found a crazy solution.

In the midst of World War II, February 1942, to be more exact, the Japanese fleet gave the combined Dutch-American-Australian-British fleet a beating that almost wiped them out completely, during the Battle of the Java Sea. The defeat brought about the Japanese occupation of the entire Netherlands East Indies. After the battle ended, only four Dutch warships were left in the Dutch East Indies. They knew there was no way they would be able to take down the Japanese fleet by themselves, so they decided to try to escape to Australia. The failed attempt left three of the four ships sunk, and one in hiding. The problem they had, was that the seas were full of warships and the skies were swarming with Japanese planes. It was going to be virtually impossible to sail the 1,000 miles of ocean to safety. The HNLMS Abraham Crijnssen, which was the last ship, had a big problem, for which they found a crazy solution.

The HNLMS Abraham Crijnssen was a slow-moving minesweeper vessel that could get up to about 15 knots. It also had very few guns…a single 3-inch gun and two Oerlikon 20mm cannons…making it a sitting duck for the Japanese bombers that circled above. The secret weapon of the HNLMS Abraham Crijnssen, however, was it’s  captain, who came up with a crazy scheme to disguise the ship as a small island. The Abraham Crijnssen was a relatively small ship, but it was still a big object, measuring approximately 180 feet long and 25 feet wide. The crew used foliage from island vegetation and gray paint to make the ship’s hull look like rock faces. They figured that it was better to be a camouflaged ship in deep trouble, than a completely exposed ship. Still, logic said that the Japanese would probably notice a mysterious moving island, and they might wonder what would happen if they shot at it. So,the plan came about that during the day, they would not move…thereby actually becoming an island.

captain, who came up with a crazy scheme to disguise the ship as a small island. The Abraham Crijnssen was a relatively small ship, but it was still a big object, measuring approximately 180 feet long and 25 feet wide. The crew used foliage from island vegetation and gray paint to make the ship’s hull look like rock faces. They figured that it was better to be a camouflaged ship in deep trouble, than a completely exposed ship. Still, logic said that the Japanese would probably notice a mysterious moving island, and they might wonder what would happen if they shot at it. So,the plan came about that during the day, they would not move…thereby actually becoming an island.

Moving only at night, the ship was able to blend in with the thousands of other tiny islands around Indonesia, and miraculously the Japanese didn’t notice the moving island. The Crijnssen managed to go undetected by Japanese planes and avoid the destroyer that sank the other Dutch warships, surviving the eight-day journey to Australia and reuniting with Allied forces, and fought with the Allies until the end of the war. During those years of service under the Australian Navy flag, Abraham Crijnssen detected a submarine, while escorting a convoy to Sydney through the Bass Strait, on 26th of January 1943. Along with the Australian HMAS Bundaberg, they depth charged the submarine. No wreckage of the submarine was found, nor was the kill  confirmed, but the ex-minesweeper Abraham Crijnssen suffered some damage due to hastily released depth charges. Several fittings and pipes were damaged, and all of her centerline had to be replaced during a week-long-dry docking. After this incident, the ship was returned to Royal Netherlands Navy service on May 5, 1943, spending the rest of the war in Australian waters. Abraham Crijnssen ended its WWII career just like the ship started it, as a minesweeper that was responsible for clearing mines in Kupang Harbor before the arrival of an RAN force to accept the Japanese surrender of Timor.

confirmed, but the ex-minesweeper Abraham Crijnssen suffered some damage due to hastily released depth charges. Several fittings and pipes were damaged, and all of her centerline had to be replaced during a week-long-dry docking. After this incident, the ship was returned to Royal Netherlands Navy service on May 5, 1943, spending the rest of the war in Australian waters. Abraham Crijnssen ended its WWII career just like the ship started it, as a minesweeper that was responsible for clearing mines in Kupang Harbor before the arrival of an RAN force to accept the Japanese surrender of Timor.

When we think about war machines, we think of planes, tanks, ships, and even horses, but we very seldom…if ever, think of bicycles. Nevertheless, bicycles were used in a number of wars, and even continue to be used to this day. The late 19th century brought several experiments into the possible role of bicycles and cycling within military establishments, primarily because they can carry more equipment and travel longer distances than walking soldiers could. The development of pneumatic tires coupled with shorter, sturdier frames in the late 19th century led military establishments to investigate the possibility of bicycles in combat. To some extent, bicyclists took over the functions of dragoons, especially as messengers and scouts, substituting for horses in warfare. Bicycle units or detachments were in existence by the end of the 19th century in most armies.

When we think about war machines, we think of planes, tanks, ships, and even horses, but we very seldom…if ever, think of bicycles. Nevertheless, bicycles were used in a number of wars, and even continue to be used to this day. The late 19th century brought several experiments into the possible role of bicycles and cycling within military establishments, primarily because they can carry more equipment and travel longer distances than walking soldiers could. The development of pneumatic tires coupled with shorter, sturdier frames in the late 19th century led military establishments to investigate the possibility of bicycles in combat. To some extent, bicyclists took over the functions of dragoons, especially as messengers and scouts, substituting for horses in warfare. Bicycle units or detachments were in existence by the end of the 19th century in most armies.

By World War I, the level terrain in Belgian was well used by military cyclists, prior to the onset of trench  warfare. Each of the four Belgian carabinier battalions included a company of cyclists, equipped with a brand of folding, portable bicycle named the Belgica. A regimental cyclist school gave training in map reading, reconnaissance, reporting, and the carrying of verbal messages. Attention was paid to the maintenance and repair of the machine itself. The bicycle could be used to ride when it was feasible, and carried when the pat was not suitable to riding. The bicycle made no noise, so unless the trail was littered with twigs, the bicycle make very little noise. Sneaking up on the enemy was possible.

warfare. Each of the four Belgian carabinier battalions included a company of cyclists, equipped with a brand of folding, portable bicycle named the Belgica. A regimental cyclist school gave training in map reading, reconnaissance, reporting, and the carrying of verbal messages. Attention was paid to the maintenance and repair of the machine itself. The bicycle could be used to ride when it was feasible, and carried when the pat was not suitable to riding. The bicycle made no noise, so unless the trail was littered with twigs, the bicycle make very little noise. Sneaking up on the enemy was possible.

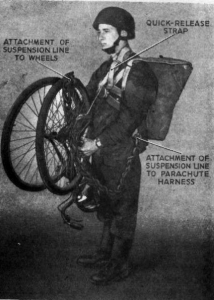

In the United States, the most extensive experimentation on bicycle units was carried out by 1st Lieutenant Moss, of the 25th United States Infantry (Colored), which was made up of African American infantry soldiers with European American officers. Using a variety of cycle models, Moss and his troops carried out extensive bicycle journeys covering between 800 and 1,900 miles. Late in the 19th century, the United States Army tested the bicycle’s suitability for cross-country troop transport. Buffalo Soldiers stationed in Montana rode bicycles across roadless landscapes for hundreds of miles at high speed. The “wheelmen” traveled the 1,900 Miles to Saint Louis, Missouri in 34 days with an average speed of over 6 miles per hour. The bicycles were even used in the paratrooper deployment. These bicycles not only folded up, but they were equipped with an on board rifle. I don’t know how hard it was to handle a gun while riding a bike, but I’m sure it was a relief to have your gun right there.

The first known use of the bicycle in combat occurred during the Jameson Raid, in which cyclists carried messages. In the Second Boer War, military cyclists were used primarily as scouts and messengers. One unit  patrolled railroad lines on specially constructed tandem bicycles that were fixed to the rails. Several raids were conducted by cycle-mounted infantry on both sides; the most famous unit was the Theron se Verkenningskorps (Theron Reconnaissance Corps) or TVK, a Boer unit led by the scout Daniel Theron, whom British commander Lord Roberts described as “the hardest thorn in the flesh of the British advance.” Roberts placed a reward of £1,000 on Theron’s head…dead or alive…and dispatched 4,000 soldiers to find and eliminate the TVK. While scouting alone on a road near Gatsrand, about 3.7 miles north of present-day Fochville, he encountered seven members of Marshall’s Horse and was killed in action.

patrolled railroad lines on specially constructed tandem bicycles that were fixed to the rails. Several raids were conducted by cycle-mounted infantry on both sides; the most famous unit was the Theron se Verkenningskorps (Theron Reconnaissance Corps) or TVK, a Boer unit led by the scout Daniel Theron, whom British commander Lord Roberts described as “the hardest thorn in the flesh of the British advance.” Roberts placed a reward of £1,000 on Theron’s head…dead or alive…and dispatched 4,000 soldiers to find and eliminate the TVK. While scouting alone on a road near Gatsrand, about 3.7 miles north of present-day Fochville, he encountered seven members of Marshall’s Horse and was killed in action.

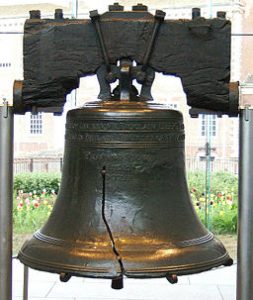

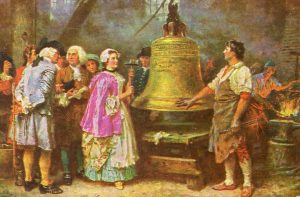

Everyone has heard of the Liberty Bell. The bell was ordered in 1751, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Pennsylvania’s original constitution. The Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly ordered the 2,000 pound copper and tin bell. The bell was placed in the Pennsylvania State House, which is now known as Independence Hall. The bell rang out summoning citizens to the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence, by Colonel John Nixon. The document was adopted by delegates to the Continental Congress meeting in the State House on July 4th, however, the Liberty Bell, inscribed with the Biblical quotation, “Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land unto All the Inhabitants Thereof,” was not rung until the Declaration of Independence was returned from the printer on July 8th.

Everyone has heard of the Liberty Bell. The bell was ordered in 1751, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Pennsylvania’s original constitution. The Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly ordered the 2,000 pound copper and tin bell. The bell was placed in the Pennsylvania State House, which is now known as Independence Hall. The bell rang out summoning citizens to the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence, by Colonel John Nixon. The document was adopted by delegates to the Continental Congress meeting in the State House on July 4th, however, the Liberty Bell, inscribed with the Biblical quotation, “Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land unto All the Inhabitants Thereof,” was not rung until the Declaration of Independence was returned from the printer on July 8th.

The bell was made of inferior materials, and cracked during the first test. It was recast twice and finally hung from the State House steeple in June 1753. The bell was rung on special occasions, such as when King George III ascended to the throne in 1761, and to call the people together to discuss such important things as the controversial Stamp Act of 1765. With the outbreak of the American Revolution in April 1775, the bell was rung to announce the battles of Lexington and Concord. Of course, the most famous time it was rung was July 8, 1776, when it summoned Philadelphia citizens for the first reading of the Declaration of Independence.

When the British were advancing on Philadelphia in the fall of 1777, the bell was removed and hidden in Allentown to protect it from being melted down by the British to be used for cannons. Following the defeat of the British in 1781, the bell was returned to it’s place in Philadelphia which was the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800. In addition to marking important events, the bell was used as a part of the celebrations such as George Washington’s birthday on February 22, and Independence Day on July 4. In 1839, bell was first given it’s name when it was coined the Liberty Bell in a poem.

As to the crack that finally made the Liberty Bell unsuitable for ringing, there has been some dispute. It was  finally agreed upon that the bell suffered a major break while tolling for the funeral of the chief justice of the United States, John Marshall, in 1835, and in 1846 the crack expanded to its present size while in use to mark Washington’s birthday. After that date, it was decided that the bell was unsuitable for ringing, but it was still ceremoniously tapped on occasion to commemorate important events. On June 6, 1944, when Allied forces invaded France, the sound of the bell’s dulled ring was broadcast by radio across the United States. In 1976, the Liberty Bell was moved to a new pavilion about 100 yards from Independence Hall in preparation for America’s bicentennial celebrations. The Liberty Bell will always be a symbol of patriotism and liberty in my mind.

finally agreed upon that the bell suffered a major break while tolling for the funeral of the chief justice of the United States, John Marshall, in 1835, and in 1846 the crack expanded to its present size while in use to mark Washington’s birthday. After that date, it was decided that the bell was unsuitable for ringing, but it was still ceremoniously tapped on occasion to commemorate important events. On June 6, 1944, when Allied forces invaded France, the sound of the bell’s dulled ring was broadcast by radio across the United States. In 1976, the Liberty Bell was moved to a new pavilion about 100 yards from Independence Hall in preparation for America’s bicentennial celebrations. The Liberty Bell will always be a symbol of patriotism and liberty in my mind.