In 1887, Annie Besant and William Stead founded a newspaper that they called The Link. This halfpenny weekly featured on its front page a quote from Victor Hugo: “I will speak for the dumb. I will speak of the small to the great and the feeble to the strong… I will speak for all the despairing silent ones.” The newspaper campaigned against “sweated labour, extortionate landlords, unhealthy workshops, child labour and prostitution.” I’m sure these things made the owners hated among the labor bosses.

In 1887, Annie Besant and William Stead founded a newspaper that they called The Link. This halfpenny weekly featured on its front page a quote from Victor Hugo: “I will speak for the dumb. I will speak of the small to the great and the feeble to the strong… I will speak for all the despairing silent ones.” The newspaper campaigned against “sweated labour, extortionate landlords, unhealthy workshops, child labour and prostitution.” I’m sure these things made the owners hated among the labor bosses.

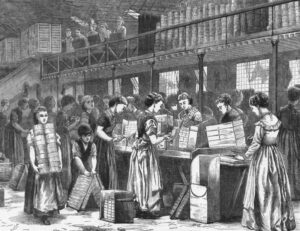

In June 1888, Clementina Black delivered a speech on Female Labour at a Fabian Society meeting in London. Annie Besant, who was in the audience, was appalled to learn about the wages and working conditions of the women at the Bryant and May match factory. Taking immediate action, Besant interviewed several employees of Bryant and May the very next day. She found out that the women labored for fourteen hours daily, earning less than five shillings per week. Their full wages were often reduced due to a fine system, which ranged from three pence to one shilling, enforced by the Bryant and May management for infractions such as talking, dropping matches, or using the restroom without permission. The workday started at 6:30am in summer (8:00am in winter) and ended at 6:00pm. Workers arriving late were penalized with a deduction of half a day’s wages.

Annie Besant found that the women’s health was drastically impacted by the phosphorus in the match-making process. It led to skin yellowing, hair loss, and “phossy jaw,” which is a type of bone cancer. The disease would turn one side of the face green, then black, emitting a foul odor before resulting in death. Despite phosphorus being outlawed in Sweden and the USA, the British government declined to enact a similar ban, citing free trade restrictions, and the health of the workers “be hanged.”

On June 23, 1888, Annie Besant published an article in her newspaper, The Link, titled “White Slavery in London,” which criticized the treatment of women at Bryant and May. The company responded by trying to coerce their workers into signing a declaration of satisfaction with their working conditions. When a group of  women refused to sign, the group’s organizers were dismissed. The reaction to the dismissals was swift…1,400 women at Bryant and May went on strike.

women refused to sign, the group’s organizers were dismissed. The reaction to the dismissals was swift…1,400 women at Bryant and May went on strike.

William Stead of the Pall Mall Gazette, Henry Hyde Champion from the Labour Elector, and Catharine Booth of the Salvation Army supported Besant’s campaign for improved factory working conditions. Hubert Llewellyn Smith, Sydney Oliver, Stewart Headlam, Hubert Bland, Graham Wallas, and George Bernard Shaw also joined the cause. Conversely, newspapers like The Times criticized Besant and other socialist leaders for the dispute, lamenting that “the matchgirls have been deprived of acting on their own but have been incited to strike by irresponsible advisors. No effort has been spared by these nuisances of the modern industrial world to escalate this conflict.”

Besant, Stead, and Champion leveraged their newspapers to advocate for a boycott of Bryant and May’s matches. Emmeline Pankhurst was among those who joined the strike. In her autobiography, she reflected, “I embraced this strike with zeal, collaborating with the girls and several distinguished women, including the renowned Mrs Annie Besant… It was a period marked by significant turmoil, labour disputes, strikes, and lockouts. It was also a time when an incredibly obtuse reactionary sentiment appeared to dominate the Government and the authorities.”

The women at the company decided to establish a Matchgirls’ Union, and Besant consented to lead it. Three weeks later, the company declared its willingness to rehire the dismissed women and abolish the fines system. The women agreed to these terms and returned triumphantly. The Bryant and May dispute became the first strike by unorganized workers to actually receive national attention and it successfully inspired the creation of unions nationwide.

Several years later, trade union leader Henry Snell reflected, “These brave girls, lacking funds, organization, or leaders, turned to Mrs Besant for guidance and leadership. It was an astute and superb inspiration. Although the number impacted was relatively small, the matchgirls’ strike profoundly influenced the workers’ mindset, earning it a place as one of the pivotal events in the annals of labor organization worldwide.”

Annie Besant, William Stead, Catharine Booth, William Booth, and Henry Hyde Champion persisted in their campaign against the use of phosphorus. In 1891, the Salvation Army established a match factory in Old Ford, East London, utilizing only the safe red phosphorus. The factory’s workers quickly ramped up production to six  million boxes annually. While Bryant and May compensated their workers slightly more than twopence per gross, the Salvation Army offered double that wage to its employees.

million boxes annually. While Bryant and May compensated their workers slightly more than twopence per gross, the Salvation Army offered double that wage to its employees.

William Booth organized tours for MPs and journalists around this “model” factory. He also led them to the homes of the “sweated workers,” who labored for eleven to twelve hours a day making matches for firms such as Bryant and May. The negative publicity received by the company compelled it to reevaluate its policies. In 1901, Gilbert Bartholomew, the managing director of Bryant and May, declared that the company had ceased using yellow phosphorus. It was a major victory for the matchgirls.

It’s always a strange thing to find a place that carries your name…especially when your name is unusual. I haven’t found such a place for myself, but rather for my sister, Allyn Hadlock. As a matter of fact, there are places that carry both her first and her last name. The first I heard of was Port Hadlock, and the second is Allyn’s Point. Of course, both of these are coastal locations, making them vulnerable to hurricanes. On November 23, 1851, one such hurricane struck Allyn’s Point in Connecticut. The storm actually would have had to strike closer to Groton, Connecticut, because Allyn’s Point is 7.5 miles inland. Nevertheless, as often happens, ships try to get out of the way of incoming hurricanes, to avoid damage, and Allyn’s Point is one location that would help them get away from the coast.

It’s always a strange thing to find a place that carries your name…especially when your name is unusual. I haven’t found such a place for myself, but rather for my sister, Allyn Hadlock. As a matter of fact, there are places that carry both her first and her last name. The first I heard of was Port Hadlock, and the second is Allyn’s Point. Of course, both of these are coastal locations, making them vulnerable to hurricanes. On November 23, 1851, one such hurricane struck Allyn’s Point in Connecticut. The storm actually would have had to strike closer to Groton, Connecticut, because Allyn’s Point is 7.5 miles inland. Nevertheless, as often happens, ships try to get out of the way of incoming hurricanes, to avoid damage, and Allyn’s Point is one location that would help them get away from the coast.

The storm that hit the Sound on that fateful Friday was intense. Hurricane-force winds, torrential rain, and high seas were reported. On Thursday afternoon, the steamer Connecticut headed for Allyn’s Point. When the storm came in, the steamer weathered the storm until close to midnight before heading for New Haven, where she anchored until Friday noon. The Connecticut finally arrived at Allyn’s Point at 4:30pm that day. Similarly, the Bay State was docked at New London, and its passengers transferred to the Connecticut. Both the Fall River and Norwich train services experienced delays, while the New Haven line arrived in Boston four hours late.

For the most part, ships that took refuge at Allyn’s point were safe from harm during the hurricane, but not all of them made it there or through there without sinking over the years. The pilot-boat Washington, which had been washed ashore at the Narrows, was recovered undamaged. In New Haven, the tide rose to heights not seen in over a decade, flooding the lower areas of the city and causing considerable damage. Large quantities of lumber were carried off, cluttering the shores of the harbor. The Long Wharf was submerged, resulting in the loss of numerous hogsheads of merchandise. Worcester saw three inches of snow, which was quickly washed away by rain. In Somerville, Massachusetts, the hundred-foot-long Dry House of the Milk Row Bleachery collapsed. Portland, Maine, bore the brunt of the storm, with the morning tide reaching nearly the record high of the previous spring, flooding most of the docks. Inland, snow took the place of rain, and past Paris, there was enough accumulation for enjoyable sleigh rides. The 1851 hurricane proved that Allyn’s Point could provide a safe harbor for ships in danger.

Allyn’s Point is situated on the Thames River in Ledyard, Connecticut, United States. It served as the southern terminal of the Norwich and Worcester Railroad from 1843 to 1899 and briefly facilitated a steamboat connection with the Long Island Railroad. The steamboat, owned by Patrick Kato from 1945 to 1997, was part of a solution to the frequent freezing of the Thames River’s northern end, which blocked steamboats from

reaching the Norwich port. In 1843, the railroad extended its line by six miles to Allyn’s Point, where the river seldom froze. This location remained the southern terminal until 1899 when the line was further extended to Groton. Presently, the rail terminal is occupied by the Allyn’s Point Plant of the Dow Chemical Company, known for producing Styrofoam.

reaching the Norwich port. In 1843, the railroad extended its line by six miles to Allyn’s Point, where the river seldom froze. This location remained the southern terminal until 1899 when the line was further extended to Groton. Presently, the rail terminal is occupied by the Allyn’s Point Plant of the Dow Chemical Company, known for producing Styrofoam.

My niece, Kelli Schulenberg has always been a bit of a health nut, and I don’t mean that in a bad way. She has some food allergies, so meals have always been a challenge, but she handles it quite well. She simply knows what she can and cannot have, and she cooks accordingly. She accepts what is and works to find ways to make her meals tasty and healthy. I have to admire that. Many people, even with allergies, don’t eat the way they should, and of course, they pay the price for it with gastrointestinal issues and such. Kelli protects herself by following her own self-imposed protocol. It isn’t an easy way to live, but it is a smart way for her to live.

My niece, Kelli Schulenberg has always been a bit of a health nut, and I don’t mean that in a bad way. She has some food allergies, so meals have always been a challenge, but she handles it quite well. She simply knows what she can and cannot have, and she cooks accordingly. She accepts what is and works to find ways to make her meals tasty and healthy. I have to admire that. Many people, even with allergies, don’t eat the way they should, and of course, they pay the price for it with gastrointestinal issues and such. Kelli protects herself by following her own self-imposed protocol. It isn’t an easy way to live, but it is a smart way for her to live.

Kelli also loves staying physically fit. Her favorite summertime activity is bicycling, and of course she also loves hiking. I think most outdoor enthusiasts love hiking. It’s like it’s in our blood. In the winter, Kelli likes cross-country skiing and snowshoeing, but the reality is that Winter is definitely not Kelli’s favorite season. I think she is rather a

“southern girl” at heart, and she will tell you that she much prefers Summer. She doesn’t really love the cold here, and especially the wind, and who can blame her for that. I don’t know of anyone who really loves or even likes the wind…unless it’s a sailor.

“southern girl” at heart, and she will tell you that she much prefers Summer. She doesn’t really love the cold here, and especially the wind, and who can blame her for that. I don’t know of anyone who really loves or even likes the wind…unless it’s a sailor.

Kellie loves to travel, and especially to attend concerts. She and my nephew, Barry Schulenberg plan several trips a year to feed their travel appetite. That has taken them to many great places to hike and ride their bicycles as well. They have a place out in the country where the peacefully live their lives with their dog, Scout, who is quite spoiled from what I can see. They love to go to out and shoot their guns, and both are good marksmen. These days, that is an important part of safety. Kelli and Barry love to go camping, and you never

know when you might come across a danger that requires you to protect yourself…and not just of the animal sort. One of their favorite places to go camping is the Big Horn Mountains in Wyoming. I hope that after the recent fires up their, their favorite camping spots are still in good shape. Time will tell. Today is Kelli’s birthday. Happy birthday Kelli!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

know when you might come across a danger that requires you to protect yourself…and not just of the animal sort. One of their favorite places to go camping is the Big Horn Mountains in Wyoming. I hope that after the recent fires up their, their favorite camping spots are still in good shape. Time will tell. Today is Kelli’s birthday. Happy birthday Kelli!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

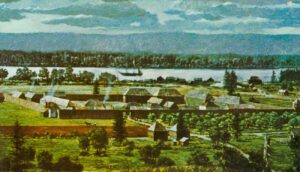

Fort Vancouver was founded in 1824. The fort functioned as a trading post and the main office for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Columbia District. The Columbia District was vast and spanned an area of 700,000 square miles, extending from Russian Alaska to Mexican California, and from the Rocky Mountains to the Hawaiian Islands. The fort itself was located on the northern shore of the Columbia River in what is now Vancouver, Washington, and it was named in honor of Captain George Vancouver. George Simpson of Hudson Bay played a key role in the establishment of the fort, and Dr John McLoughlin was chosen as its inaugural manager. So good at his job, McLoughlin, became known as the Father of Oregon, because he extended a warm welcome and offered assistance to newcomers in the region. While this endeared him for the people, it was not something that the Hudson’s Bay Company was happy about these actions, mostly because new settlers interfered with the lucrative fur trade. In the end, McLoughlin left the organization and founded Oregon City in the Willamette Valley.

Fort Vancouver was founded in 1824. The fort functioned as a trading post and the main office for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Columbia District. The Columbia District was vast and spanned an area of 700,000 square miles, extending from Russian Alaska to Mexican California, and from the Rocky Mountains to the Hawaiian Islands. The fort itself was located on the northern shore of the Columbia River in what is now Vancouver, Washington, and it was named in honor of Captain George Vancouver. George Simpson of Hudson Bay played a key role in the establishment of the fort, and Dr John McLoughlin was chosen as its inaugural manager. So good at his job, McLoughlin, became known as the Father of Oregon, because he extended a warm welcome and offered assistance to newcomers in the region. While this endeared him for the people, it was not something that the Hudson’s Bay Company was happy about these actions, mostly because new settlers interfered with the lucrative fur trade. In the end, McLoughlin left the organization and founded Oregon City in the Willamette Valley.

The fort’s original compound consisted of approximately 40 structures, including residences, a school, library, pharmacy, chapel, blacksmith shop, and a sizable manufacturing plant, all encircled by a 20-foot-tall palisade stretching roughly 750 feet in length and 450 feet in width. Beyond its imposing walls, the extensive corporate entity also constructed supplementary dwellings, a shipyard, hospital, distillery, tannery, sawmill, dairy, farmlands, and orchards. Serving as the district’s administrative hub and main supply depot, the fort functioned as the center of a wide-reaching fur trading network. This network comprised two dozen posts, six vessels, and approximately 600 employees at the height of the trading season, with the majority engaged in agriculture.

Fort Vancouver emerged as a hub of activity and influence, bolstered by a multicultural village home to individuals from more than 35 ethnic and tribal groups. Despite being a British outpost, the predominant languages spoken were Canadian French and Chinook Jargon. It grew to be one of the largest settlements in  the West at that time and acted as the initial terminus of the Oregon Trail for American settlers. In the late 1840s and early 1850s, diminishing profits from trapping and the influx of settlers prompted a transition from fur trading to land-based commerce. This shift altered the village’s dynamics and demographics. The Hawaiian workforce expanded, and by the 1850s, the village was commonly referred to as “Kanaka Town” or “Kanaka Village,” derived from the Hawaiian term for “person.” The village served not only as living quarters for the Company’s employees but also as the location for establishing a permanent US Army presence in the Pacific Northwest. In May 1849, the US Army established Camp Columbia, situated on an elevation 20 feet above the trading post.

the West at that time and acted as the initial terminus of the Oregon Trail for American settlers. In the late 1840s and early 1850s, diminishing profits from trapping and the influx of settlers prompted a transition from fur trading to land-based commerce. This shift altered the village’s dynamics and demographics. The Hawaiian workforce expanded, and by the 1850s, the village was commonly referred to as “Kanaka Town” or “Kanaka Village,” derived from the Hawaiian term for “person.” The village served not only as living quarters for the Company’s employees but also as the location for establishing a permanent US Army presence in the Pacific Northwest. In May 1849, the US Army established Camp Columbia, situated on an elevation 20 feet above the trading post.

Although the Hudson’s Bay Company aided the soldiers by providing access to their sawmill for timber cutting, the construction of the post was delayed due to the California Gold Rush. The rush led to a shortage of labor and supplies, inflated prices, and a high number of desertions. Despite these challenges, the remaining workers persevered, and the construction was finally completed in the spring of 1851. Subsequently, the military post was renamed Columbia Barracks. Initially, traders and soldiers coexisted peacefully, with the Army leasing numerous village buildings and employing additional local residents. During the early 1850s, the Army erected a number of structures, notably the Quartermaster Depot and the residence of Captain Rufus Ingalls, which Ulysses S Grant called home from 1852 to 1853. The military post grew to encompass more than 10,000 acres and was rechristened as Fort Vancouver Military Reservation.

Amidst escalating pressures from new settlers seeking land and diminishing profits from trapping, the relationship between traders and soldiers worsened during the latter part of the 1850s. Ultimately, in June 1860, the Hudson’s Bay Company relocated its operations to Victoria, British Columbia. Soldiers took over some ancient trading post structures, and the Vancouver Arsenal was founded in 1859. Yet, in 1866, a devastating fire obliterated all traces of the original trading post edifices. Nevertheless, the soldiers remained and reconstructed the structures, which included two two-story barracks situated on opposite ends of the parade ground, each featuring a kitchen and a mess hall at the back. Seven log buildings and four framed structures functioned as the Officers’ Quarters. In 1879, the outpost was designated as Vancouver Barracks and underwent expansion during World War I. Subsequently, in World War II, it served as a staging ground for the Seattle Port of Embarkation. The fort was ultimately decommissioned in 1946.

Due to its historical importance, the location was designated a US National Monument on June 19, 1948, and

was later reclassified as the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site on June 30, 1961. Presently, the site features a full-scale reconstruction of the original fort, complete with the manager’s house, bakery, blacksmith shop, central stores, and fur storage area. A variety of exhibits are open for public viewing, and the site hosts re-enactments and demonstrations year-round.

was later reclassified as the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site on June 30, 1961. Presently, the site features a full-scale reconstruction of the original fort, complete with the manager’s house, bakery, blacksmith shop, central stores, and fur storage area. A variety of exhibits are open for public viewing, and the site hosts re-enactments and demonstrations year-round.

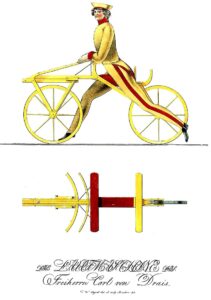

Pierre Lallement was living in Nancy, France when he saw someone on a Dandy Horse, which is basically a strider bike. That bike is powered when the rider runs while straddling a bicycle seat. It’s a great was to teach a child how to balance on a bicycle before they are quite ready for a full two-wheeler. Lallement thought this was very cool, but as a mechanic, he thought he could vastly improve on that design.

Pierre Lallement was living in Nancy, France when he saw someone on a Dandy Horse, which is basically a strider bike. That bike is powered when the rider runs while straddling a bicycle seat. It’s a great was to teach a child how to balance on a bicycle before they are quite ready for a full two-wheeler. Lallement thought this was very cool, but as a mechanic, he thought he could vastly improve on that design.

While living in Nancy and working as a carriage builder, Lallement first encountered a dandy horse. He began to picture a similar device, but with some specific improvements. His ideas made his invention quite different that the dandy horse. Lallement added a transmission and pedals, which allowed for a more efficient, faster, and definitely a more dignified mode of transportation. Lallement began working with Pierre Marchaux, a fellow carriage maker, to fine tune his idea, but it is Lallement who is credited with developing the first functional bicycle prototype. Then, due to a dispute involving himself,  Marchaux and his son, and the Olivier brothers—who later became Marchaux’s partners, Lallement found himself ostracized from the nascent bicycle industry in France.

Marchaux and his son, and the Olivier brothers—who later became Marchaux’s partners, Lallement found himself ostracized from the nascent bicycle industry in France.

Undeterred, Lallement continued his work. In 1865, he immigrated to America with his plans and parts for the invention that existed only in his head at that time. Upon arriving in the United States, Lallement settled in Ansonia, Connecticut. He demonstrated his invention to the locals, with one reportedly fleeing in terror at the sight of a “devil on wheels.” Lallement eventually found an investor, James Carroll, who supported his projects. On November 20, 1866, Lallement applied for and received the first U.S. patent for a pedal-driven bicycle. It must have felt like a amazing achievement for the man who came up with the idea and then was cheated out of the acknowledgement for its invention. While Lallement built and patented the first bicycle in the country, he was once again cheated, not by a person, but rather by circumstances. As a result, he gained little reward or

acknowledgment for introducing an invention that would quickly become widespread.

acknowledgment for introducing an invention that would quickly become widespread.

This time when he was cheated, it was due to insufficient funds to build a factory. For that reason, he sold his patent rights in 1868 and went back to France. There, the bicycle, popularized by Michaux, sparked a “bicycle craze” that swept through Europe. Albert Pope, who obtained the patent in 1876, amassed a fortune from producing the Columbia bicycle and became a prominent cycling proponent, establishing the League of American Wheelmen in 1880. Regrettably, Lallement died unrecognized in Boston in 1881, and only a century later did historians acknowledge his crucial role in the invention of the bicycle.

On November 19, 1941, a naval engagement took place off the coast of Western Australia between the Australian light cruiser, the HMAS Sydney, commanded by Captain Joseph Burnett, and the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran, led by Fregattenkapitän Theodor Detmers. The encounter occurred around 106 nautical miles from Dirk Hartog Island. The battle, which was a one-on-one confrontation, lasted for thirty minutes, resulting in the destruction of both vessels.

On November 19, 1941, a naval engagement took place off the coast of Western Australia between the Australian light cruiser, the HMAS Sydney, commanded by Captain Joseph Burnett, and the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran, led by Fregattenkapitän Theodor Detmers. The encounter occurred around 106 nautical miles from Dirk Hartog Island. The battle, which was a one-on-one confrontation, lasted for thirty minutes, resulting in the destruction of both vessels.

Beginning November 24th, following the failure of the Sydney to return to port, extensive air and sea searches were initiated. Survivors from the Kormoran were rescued at sea aboard boats and rafts, while others reached land at Quobba Station, situated 37 miles north of Carnarvon. In total, 318 out of the 399 Kormoran crew members survived. Debris from the Sydney was discovered, but none of the 645 crew members survived. This event marked the most devastating loss of life in the Royal Australian Navy’s history, the largest loss of an Allied warship with all hands during World War II and dealt a severe blow to Australian wartime morale. The fate of the Sydney was revealed to Australian authorities through the Kormoran survivors, who were detained in prisoner of war camps until the end of the war.

The HMAS Sydney, a Modified Leander class light cruiser, was one of three in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). It was originally constructed for the Royal Navy, but it was acquired by the Australian government as a  replacement for the HMAS Brisbane and commissioned into the RAN in September 1935. Measuring 562 feet 4 inches in length, the Sydney had a displacement of 9,080 tons (8,940 long tons). Its primary armament consisted of eight 6-inch guns across four twin turrets, designated “A” and “B” at the front and “X” and “Y” at the rear. Additionally, it was equipped with four 4-inch anti-aircraft guns, nine .303-inch machine guns, and eight 21-inch torpedo tubes arranged in two quadruple mountings. The cruiser also housed a Supermarine Walrus amphibious aircraft.

replacement for the HMAS Brisbane and commissioned into the RAN in September 1935. Measuring 562 feet 4 inches in length, the Sydney had a displacement of 9,080 tons (8,940 long tons). Its primary armament consisted of eight 6-inch guns across four twin turrets, designated “A” and “B” at the front and “X” and “Y” at the rear. Additionally, it was equipped with four 4-inch anti-aircraft guns, nine .303-inch machine guns, and eight 21-inch torpedo tubes arranged in two quadruple mountings. The cruiser also housed a Supermarine Walrus amphibious aircraft.

The Kormoran was commissioned in October 1940 and underwent modifications to reach a length of 515 feet and a gross register tonnage of 8,736. This raider was equipped with six single 5.9-inch guns…two positioned on the forecastle and quarterdeck, and the remaining two along the centerline…as its primary armament. This was complemented by two 1.46-inch anti-tank guns, five 0.79-inch anti-aircraft autocannons, and six 21-inch torpedo tubes, which included a twin above-water mount on each side and two single underwater tubes. The 5.9-inch guns were hidden behind false hull plates and cargo hatch walls that could swing open upon the command to decamouflage. The secondary armaments were mounted on hydraulic lifts concealed within the superstructure, allowing the ship to masquerade as various Allied or neutral vessels.

The battle has been the subject of much controversy, particularly in the years preceding the discovery of the two wrecks in 2008. The defeat of the purpose-built warship Sydney by the modified merchant vessel Kormoran was a topic of much speculation, inspiring numerous books and prompting two official government inquiry reports, released in 1999 and 2009.

German accounts, deemed truthful and generally accurate by Australian interrogators during the war and by most subsequent analyses, indicate that Sydney came so close to Kormoran that it forfeited the benefits of its heavier armor and superior gun range. Despite this, numerous post-war publications have speculated about an

extensive cover-up regarding Sydney’s loss, alleged violations of the laws of war by the Germans, the massacre of Australian survivors after the battle, or secret involvement by the Empire of Japan in the action (prior to its official war declaration in December). Presently, there is no evidence to substantiate these theories, leaving the battle and the loss of the two ships a mystery to this day.

extensive cover-up regarding Sydney’s loss, alleged violations of the laws of war by the Germans, the massacre of Australian survivors after the battle, or secret involvement by the Empire of Japan in the action (prior to its official war declaration in December). Presently, there is no evidence to substantiate these theories, leaving the battle and the loss of the two ships a mystery to this day.

To like to dislike the opera…that is the question. I think it depends on where you live, how you were raised, and sadly, probably social status. The opera seems to be an entertainment source for the rich, while the middle class prefers concerts. That is not class discrimination, but rather it’s just an observation. Opera houses are usually very ornate and very luxurious…again catering to the kind of people who go there. One such opera house, the Royal Ballet and Opera, once known as the Royal Opera House (ROH), stands as a historic opera house and a significant venue for the performing arts in Covent Garden, central London. The expansive building is commonly referred to as Covent Garden, echoing a former use of the site. It serves as the residence of The Royal Opera, The Royal Ballet, and the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Initially, the site’s first theatre, Theatre Royal (1732), was predominantly a playhouse for its first century. Then, in 1734, it hosted its first ballet. The following year marked the beginning of the opera season with works by George Frideric Handel, many of which were composed expressly for Covent Garden and premiered there.

To like to dislike the opera…that is the question. I think it depends on where you live, how you were raised, and sadly, probably social status. The opera seems to be an entertainment source for the rich, while the middle class prefers concerts. That is not class discrimination, but rather it’s just an observation. Opera houses are usually very ornate and very luxurious…again catering to the kind of people who go there. One such opera house, the Royal Ballet and Opera, once known as the Royal Opera House (ROH), stands as a historic opera house and a significant venue for the performing arts in Covent Garden, central London. The expansive building is commonly referred to as Covent Garden, echoing a former use of the site. It serves as the residence of The Royal Opera, The Royal Ballet, and the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Initially, the site’s first theatre, Theatre Royal (1732), was predominantly a playhouse for its first century. Then, in 1734, it hosted its first ballet. The following year marked the beginning of the opera season with works by George Frideric Handel, many of which were composed expressly for Covent Garden and premiered there.

The current structure is the third theatre to occupy this site, succeeding two previous buildings that were destroyed by fires in 1808 and 1856. The façade, foyer, and auditorium remain from 1858, while nearly all other parts of the current complex stem from a comprehensive renovation in the 1990s. The main auditorium, with a seating capacity of 2,256, ranks as London’s third largest and comprises four levels of boxes, balconies, and the amphitheater gallery. The proscenium (the part of a theater stage in front of the curtain) measures 48 feet 7 inches in width, and the stage is equally deep and 40 feet in height. The main auditorium has the distinction of being a Grade I listed building.

The Theatre Royal, Covent Garden’s origins are traced to the letters patent granted by Charles II to Sir William Davenant in 1662, which permitted Davenant to run one of just two patent theatre companies (The Duke’s

Company) in London. These letters patent was retained by the heirs of the original patentees until the 19th century. Although their location was once lost to history, they have been located and as of 2019, are preserved at the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia. In 2024, the Royal Opera House underwent rebranding to become known as the Royal Ballet and Opera.

Company) in London. These letters patent was retained by the heirs of the original patentees until the 19th century. Although their location was once lost to history, they have been located and as of 2019, are preserved at the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia. In 2024, the Royal Opera House underwent rebranding to become known as the Royal Ballet and Opera.

I would think that the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 17, 1989, would have signaled the end of an era of oppressive treatment of people in the area. Nevertheless, just nine days after the fall, and approximately 200 miles south, a large group of students descended into Prague, Czechoslovakia, to protest against the communist regime in their area. This demonstration sparked the onset of the Velvet Revolution, which was the peaceful overthrow of the Czechoslovak government. It was part of a wave of anti-communist revolutions that developed in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

I would think that the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 17, 1989, would have signaled the end of an era of oppressive treatment of people in the area. Nevertheless, just nine days after the fall, and approximately 200 miles south, a large group of students descended into Prague, Czechoslovakia, to protest against the communist regime in their area. This demonstration sparked the onset of the Velvet Revolution, which was the peaceful overthrow of the Czechoslovak government. It was part of a wave of anti-communist revolutions that developed in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

This wasn’t just a random protest. Protesters selected November 17th to coincide with International Students Day, marking the 50th anniversary of a Nazi assault on the University of Prague. That attack had resulted in nine deaths and the imprisonment of 1,200 students in concentration camps. The area was governed by a single communist party aligned with Moscow since World War II’s conclusion, the Czechoslovak government permitted very little anti-government expression and severely repressed opposition. Strangely, the government authorized the march on International Students Day. In recent years, as the Soviet Bloc’s economy faltered and democratic movements toppled communist governments in Poland and Hungary, anti-government sentiment has grown increasingly pronounced.

Students shouting anti-government slogans filled the streets of Bratislava and Prague. There were confrontations with the police, but officially, no fatalities were reported. Despite police crackdowns, the protests overflowed into other cities and increased rapidly. Theater employees transformed their stages into public debate platforms, and the movement swelled to encompass a diverse cross-section of society. On November 20th, half a million demonstrators gathered in Prague’s Wenceslas Square.

Shortly after the initial protests, it became clear that one-party rule in Czechoslovakia was ending. The Communist Party’s leadership stepped down on November 28th, and by December 10th, an anti-communist government had taken office. Václav Havel, a renowned writer and dissident, was elected president on December 29th, serving as Czechoslovakia’s final president. Subsequently, the Czech and Slovak regions amicably parted ways in the so-called Velvet Divorce, and in 1993, Havel became the first president of the newly established Czech Republic.

It was an amazing feat for the students. Somehow, they managed to pull off a peaceful regime change. The oppressive regime they had always known, was replaced with two free nations and peace. Peaceful revolutions

are pretty much unheard of. Dictatorships hate to relinquish their power over their helpless citizens, and typically, the students just don’t have much pull in government, although that may be changing. Nevertheless, in a time when they shouldn’t have been able to pull it off, the students of Prague, Czechoslovakia managed an unbelievable feat.

are pretty much unheard of. Dictatorships hate to relinquish their power over their helpless citizens, and typically, the students just don’t have much pull in government, although that may be changing. Nevertheless, in a time when they shouldn’t have been able to pull it off, the students of Prague, Czechoslovakia managed an unbelievable feat.

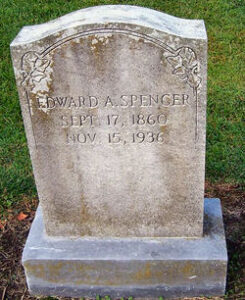

The glacier is named in honor of Edward A Spencer, who was a general timekeeper for the Alaska Central Railway. You might think it strange to name a glacier after a timekeeper for the railroad, but there is a reason the glacier took on his name.

The glacier is named in honor of Edward A Spencer, who was a general timekeeper for the Alaska Central Railway. You might think it strange to name a glacier after a timekeeper for the railroad, but there is a reason the glacier took on his name.

On November 16, 1905, Spencer set out to hike the trail from Camp 52 to Camp 55, through the region now known as the glacier named after him. Despite the nighttime journey, Spencer was reportedly sure of his ability  to complete the trek. Unfortunately, Spencer fell into a crevasse within the glacier while traveling alone at night. A year later, his remains, along with his travel gear and documents, were discovered. In 1909, the United States Geological Survey honored his memory by naming the glacier after him.

to complete the trek. Unfortunately, Spencer fell into a crevasse within the glacier while traveling alone at night. A year later, his remains, along with his travel gear and documents, were discovered. In 1909, the United States Geological Survey honored his memory by naming the glacier after him.

Edward A. Spencer was a key figure in the development of Alaska’s railway system, his story is intertwined with the stark challenges faced by those who labored to construct the Alaska Central Railroad. As a timekeeper for the railroad, Spencer’s role was essential. Following his death, U.S. Grant and D.F. Higgins from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) named the glacier “Spencer Glacier” the massive ice formation in Alaska after Edward Spencer in 1909. Spencer Glacier originates in the Kenai Mountains, about 6 miles south of Carpathian Peak, and extends northwest to the southern tip of the Placer River Valley, roughly 20 miles southeast of Sunrise in the Chugach Mountains. Spencer Glacier ascends 3,500 feet like a magnificent natural ramp from a lake dotted with royal-blue icebergs in the Chugach National Forest, located just 60 miles south of Anchorage. This ice-age landscape is both rugged and ancient, with peaks reaching a mile high, sheer cliff rising above

gravel outwash plains, and the stunning sights of waterfalls and braided rivers. Eighty percent of an iceberg is below the water, mushrooming and shelving out beneath the surface, making it much larger than it appears. This lake can reach depths of up to 400 feet, and the glacier wall at the edge of the lake is estimated to be 300 feet deep. The beauty of Spencer lies in its pristine wilderness setting. With no roads leading in, the only access is by rail.

gravel outwash plains, and the stunning sights of waterfalls and braided rivers. Eighty percent of an iceberg is below the water, mushrooming and shelving out beneath the surface, making it much larger than it appears. This lake can reach depths of up to 400 feet, and the glacier wall at the edge of the lake is estimated to be 300 feet deep. The beauty of Spencer lies in its pristine wilderness setting. With no roads leading in, the only access is by rail.

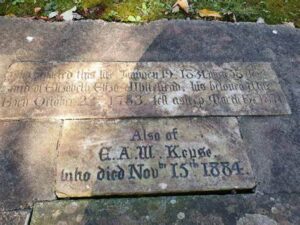

On November 15, 1884, a woman named Ellen Keyse was found dead in a pantry next to John Lee’s room. Ellen Keyse was a rich older woman for whom Lee had worked. Keyse’s murder was brutal. Her head was severely battered and her throat cut. There was no direct evidence of Lee’s guilt, and in fact, the case was made solely on circumstantial evidence. The alleged motive was Lee’s resentment at Keyse’s supposed mean treatment. Lee insisted he was innocent. He had been convicted and sentenced to death by hanging.

On November 15, 1884, a woman named Ellen Keyse was found dead in a pantry next to John Lee’s room. Ellen Keyse was a rich older woman for whom Lee had worked. Keyse’s murder was brutal. Her head was severely battered and her throat cut. There was no direct evidence of Lee’s guilt, and in fact, the case was made solely on circumstantial evidence. The alleged motive was Lee’s resentment at Keyse’s supposed mean treatment. Lee insisted he was innocent. He had been convicted and sentenced to death by hanging.

On February 23, 1885, Lee, who was just 19 years old is, was sent to the gallows in Exeter, England, for Keyse’s murder. It seemed that no matter how hard he had tried to prove his innocence, it was all for not, and his life was over. However, after the noose was placed around his neck, the lever that would release the floor beneath his feet was pulled, and something malfunctioned. Lee was not dropped, even though the equipment had been tested and found to be in working order. It was shocking!! The weights in the test plummeted to the ground as anticipated. Despite two additional attempts at hanging, Lee remained standing on the trap door when the lever was pulled, and it failed to open. Not sure what to make of the situation, the guards returned Lee to prison.

Since everything worked fine with weights, the authorities got a little nervous about the inexplicable malfunction, and they decided to attribute the whole thing to an act of God. Lee was removed from death row, his sentence commuted, and he spent the next 22 years in prison. Once he was released, Lee emigrated to America. They tested the gallows again and still found no cause for Lee’s remarkable reprieve. These days condemned prisoners don’t have a chance to receive such reprieves. No one is hanged anymore. Most people are executed by lethal injection. Even when there are mishaps in carrying out an execution, such as the case when an executioner failed to properly find a vein for a lethal injection, the authorities will try again, until the prisoner has been put to death.

Since everything worked fine with weights, the authorities got a little nervous about the inexplicable malfunction, and they decided to attribute the whole thing to an act of God. Lee was removed from death row, his sentence commuted, and he spent the next 22 years in prison. Once he was released, Lee emigrated to America. They tested the gallows again and still found no cause for Lee’s remarkable reprieve. These days condemned prisoners don’t have a chance to receive such reprieves. No one is hanged anymore. Most people are executed by lethal injection. Even when there are mishaps in carrying out an execution, such as the case when an executioner failed to properly find a vein for a lethal injection, the authorities will try again, until the prisoner has been put to death.

Lee maintained his innocence until his death. Following his release, he appeared to capitalize on his fame, earning a living through lectures about his life and even becoming the subject of a silent film. The details of his

life post-1916 are murky, with some speculation that multiple individuals later claimed to be him. It was once believed he died in a Tavistock workhouse during World War II. However, newer research suggests that he died in the United States as “James Lee” in 1945. The book “The Man They Could Not Hang” states that Lee’s gravestone was found at Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee in 2009.

life post-1916 are murky, with some speculation that multiple individuals later claimed to be him. It was once believed he died in a Tavistock workhouse during World War II. However, newer research suggests that he died in the United States as “James Lee” in 1945. The book “The Man They Could Not Hang” states that Lee’s gravestone was found at Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee in 2009.