History

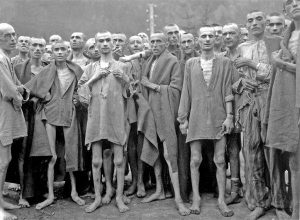

As we all know, being a prisoner of war is not a safe place to be. Growing us watching shows like “Hogan’s Heroes” gave the impression that the enemy was always nice to their prisoners, and that being in a POW camp was ok, but that wasn’t the reality of those camps. Of course, in the days of “Hogan’s Heroes” violence was just not shown on television. The world was a different place…at least for the people back home watching it on television. The reality of the POW camps was much different, as many of us have seen in newer shows about prisoners during wars. We have witnessed some of the atrocities that have been done…and we still aren’t seeing the true story, I don’t suppose.

As we all know, being a prisoner of war is not a safe place to be. Growing us watching shows like “Hogan’s Heroes” gave the impression that the enemy was always nice to their prisoners, and that being in a POW camp was ok, but that wasn’t the reality of those camps. Of course, in the days of “Hogan’s Heroes” violence was just not shown on television. The world was a different place…at least for the people back home watching it on television. The reality of the POW camps was much different, as many of us have seen in newer shows about prisoners during wars. We have witnessed some of the atrocities that have been done…and we still aren’t seeing the true story, I don’t suppose.

One example of the true story is the Sandakan Death March. For some reason, when the Japanese were close to getting caught in their brutality, they decided that the best thing to do was to take the prisoners on a march deeper into the jungle so that the evidence of their torture was not found. In reality, they could have just left the prisoners in the camp…abandoned them, and they would have likely never been caught, but apparently it was more about retaliation over their loss in the war. One such march was the Bataan Death March in the Philippians and the deadly construction of the rail line linking Burma with Thailand.

Similar to that was the Sandakan Death March in Malaysia. It is not as well known, and in fact many Australians would like it to be removed from history…not from the history books, but they wish it had never happened at all. I can fully understand that, once I found out what the Sandakan Death March was all about. Still, I don’t understand why more people don’t know about it. There were 2,700 British and Australian prisoners of war interned there by Japanese forces, as the end of World War II  approached. The Sandakan Death March has been called that Australia’s worst military tragedy.

approached. The Sandakan Death March has been called that Australia’s worst military tragedy.

Sandakan was a brutal place. About 900 British soldiers were among the prisoners of war brought to Sandakan. Most of them did not survived. Prisoners interned here died slowly. They were starved and beaten. Toward the end of the war, when the Japanese decided to flee Sandakan, most of the remaining prisoners were marched to their deaths. Those who were strong enough to make it to the end of the trail were executed. Only six…a man named Owen Campbell and five others survived…and then only because they escaped. Campbell is the last living survivor, and a reminder that when war veterans pass away, a little piece of history dies with them. That is the saddest part of such horrific loss. When people forget about the atrocities of the past, the world is destined to repeat them. When life is viewed as so insignificant, then killing becomes easy, and the consequences of these killings is somehow pushed aside and even justified. That should never be allowed to happen…not in the POW camps, or in the streets of our cities. Bruce Scott, Australia’s minister for veterans affairs, referring to the prison guards at Sandakan said, “The proud and honorable title of soldier cannot be applied to those men.” The guards forced the prisoners to begin the death march from the camp at Sandakan as the Allies were approaching. The men were already very weak from being starved and beaten. Most of the men did not survive the march…succumbing to their conditions along the way. Those that survived the march were simply executed when they reached the end of the journey. That was even more brutal than the march itself.

Campbell returned to Borneo for a ceremony in March of 1999, back to the jungles where half a century ago his  best mates were marched to their deaths. Wearing a row of ribbons and medals across his left breast pocket, Mr. Campbell, aged 82, stared straight ahead at a black slab of granite, a memorial to one of the most horrific…yet little-known…atrocities of World War II in the Pacific. “We come here to this place to help ensure that this story is not forgotten,” Bruce Ruxton, an Australian veteran, told the crowd assembled at the memorial site. “We acknowledge that great evil was done here, that inhumanity here reached such depths that shame us as human beings even to contemplate.” In a sign of the continuing sensitivities and anger surrounding the prison camp and death march, no Japanese were present at the ceremony.

best mates were marched to their deaths. Wearing a row of ribbons and medals across his left breast pocket, Mr. Campbell, aged 82, stared straight ahead at a black slab of granite, a memorial to one of the most horrific…yet little-known…atrocities of World War II in the Pacific. “We come here to this place to help ensure that this story is not forgotten,” Bruce Ruxton, an Australian veteran, told the crowd assembled at the memorial site. “We acknowledge that great evil was done here, that inhumanity here reached such depths that shame us as human beings even to contemplate.” In a sign of the continuing sensitivities and anger surrounding the prison camp and death march, no Japanese were present at the ceremony.

A military-free zone…is there such a place? Most of us don’t think so, but there is, actually. In reality, I can’t imagine fighting a war in Antarctica, but the area has actually been involved in a few disputes. Since the 1800s a number of nations, including Great Britain, Australia, Chile and Norway, have laid claim to parts of Antarctica. I think mostly the purpose for most nations is scientific research, but people have also taken trips across the frozen landscape as a way to challenge themselves. Of course, they didn’t do that in the 1800s.

A military-free zone…is there such a place? Most of us don’t think so, but there is, actually. In reality, I can’t imagine fighting a war in Antarctica, but the area has actually been involved in a few disputes. Since the 1800s a number of nations, including Great Britain, Australia, Chile and Norway, have laid claim to parts of Antarctica. I think mostly the purpose for most nations is scientific research, but people have also taken trips across the frozen landscape as a way to challenge themselves. Of course, they didn’t do that in the 1800s.

Over the years, the competing claims led to diplomatic disputes and even armed clashes. In 1948, Argentine military forces fired on British troops in an area claimed by both nations. Different nations, over the years have disputed lands and fought wars over ownership, and I guess that Antarctica was no different…even if I can’t imagine fighting over a frozen piece of land that, while it is 5,400,000 square miles of land, it is largely covered with ice and snow year round. Still, it seems to me that a continent that is that big would have plenty of room for everyone, but that did not settle the disputes.

Due to the increased number and type of incidents, together with evidence that the Soviet Union was becoming more interested in Antarctica, the United States decided to propose that the continent be made a trustee of the United Nations. This idea was rejected when none of the other nations with interests on the continent would agree to cede their claims of sovereignty to an international organization. That idea didn’t really go over too well either. By the 1950s, some officials in the United States began to press for a more active United States role in Antarctica, believing that the continent might have military potential as an area for nuclear tests. It looked like something was going to have to be done. President Dwight D Eisenhower took a different approach. US diplomats, working with their Soviet counterparts, worked out a treaty that set aside Antarctica as a military-free zone and postponed settling territorial claims for future debate. There could be “no military presence on the continent, and no testing of weapons of any sort, including nuclear weapons. Scientific ventures were allowed, and scientists would not be prohibited from traveling through any of the areas claimed by various nations.” Since the treaty did not directly tamper with issues of territorial sovereignty in Antarctica, the involved

parties included all nations with territorial claims on the continent. As such, the treaty marked a small but significant first step toward US-Soviet arms control and political cooperation. On December 1, 1959, twelve nations, including the United States and the Soviet Union, sign the Antarctica Treaty, which bans military activity and weapons testing on that continent. It was the first arms control agreement signed in the Cold War period. The treaty went into effect in June 1961, and its policies continue to govern Antarctica to this day.

parties included all nations with territorial claims on the continent. As such, the treaty marked a small but significant first step toward US-Soviet arms control and political cooperation. On December 1, 1959, twelve nations, including the United States and the Soviet Union, sign the Antarctica Treaty, which bans military activity and weapons testing on that continent. It was the first arms control agreement signed in the Cold War period. The treaty went into effect in June 1961, and its policies continue to govern Antarctica to this day.

I read an article recently, that I can’t get out of my head. “A Study Finds 66% Of US Millennials Can’t Identify What Auschwitz Is” talks about the movement to remove certain elements from world history. The picture of Auschwitz is as foreign to kids these days as the idea of “The Final Solution” was prior to Hitler’s reign of terror in Germany and parts of Europe which led to the Holocaust. The thing that shocks me most is that when they were asked, after a tour of Auschwitz, which is located in Poland, why they didn’t tear these horrible buildings down, they responded, “Oh no!! We leave them up so that we will never forget what happened here, and never allow it to happen again.” Wise words, and words that more people would do well to remember today.

I read an article recently, that I can’t get out of my head. “A Study Finds 66% Of US Millennials Can’t Identify What Auschwitz Is” talks about the movement to remove certain elements from world history. The picture of Auschwitz is as foreign to kids these days as the idea of “The Final Solution” was prior to Hitler’s reign of terror in Germany and parts of Europe which led to the Holocaust. The thing that shocks me most is that when they were asked, after a tour of Auschwitz, which is located in Poland, why they didn’t tear these horrible buildings down, they responded, “Oh no!! We leave them up so that we will never forget what happened here, and never allow it to happen again.” Wise words, and words that more people would do well to remember today.

During the past year, we have seen unrest, protests, riots, and the “cancel culture” that has become almost the norm of our time. The schools don’t teach parts of history anymore, in an act of Historical Negationism or denialism. This is not about revising history based on new information that would correct history. Usually, the purpose of historical negation is to achieve a national, political aim, by transferring war-guilt, demonizing an enemy, providing an illusion of victory, or preserving a friendship. Sometimes the purpose of a revised history is to sell more books or to attract attention with a newspaper headline. The historian James M. McPherson said that negationists would want revisionist history understood as, “a consciously-falsified or distorted interpretation of the past to serve partisan or ideological purposes in the present” All of that sounds an awful lot like what we have going on today.

Couple Historical Negationism with “taking offence” or “political correctness” and you have a recipe for disaster. In many of the riots of recent days, the rioters have torn down our historical statues. To me, it doesn’t matter if they think the statue portrays someone they find offensive, or not. That person is a pert of history, good, bad, or ugly. A hero of the South, might not be a hero of the North, but to those in the South he or she might have been. Was a war hero from Germany any less a war hero to his countrymen, simply because he was forced to fight on the side of the Nazis? I don’t think so. In fact many of the German soldiers had no idea of what was happening in their own country. I’m not standing up for the rightness, nor against the wrongness of the people

portrayed in the statues, but rather against the destruction of property. The buildings destroyed in the riots, the statues destroyed by the mobs, the looting that took place, all deemed “okay” because these places had insurance…does not make these vicious acts acceptable, or their perpetrators blameless. It’s time that we teach our children about patriotism, respect, fairness, and decency. If we don’t, we are going to find ourselves in the middle of a country that is destroyed by violence and hate. Wake up America!!

portrayed in the statues, but rather against the destruction of property. The buildings destroyed in the riots, the statues destroyed by the mobs, the looting that took place, all deemed “okay” because these places had insurance…does not make these vicious acts acceptable, or their perpetrators blameless. It’s time that we teach our children about patriotism, respect, fairness, and decency. If we don’t, we are going to find ourselves in the middle of a country that is destroyed by violence and hate. Wake up America!!

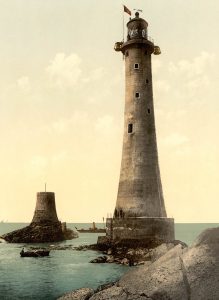

These days, we have advance warnings about potentially dangerous storms heading our way. Of course, the meteorologists aren’t always right on with their predictions, but often they are incredibly accurate. In centuries gone by, it was often the elder men, the ones who had been around a while, who had watched the sky, to see the signs that would give them clues as to coming weather. Unfortunately, on November 14, 1703, any clues they might have seen would not do any good for the people of England. The unusual weather began that day with strong winds from the Atlantic Ocean that battered the southern part of Britain and Wales. The pounding winds damaged many homes and other buildings, but the hurricane-like storm only began doing serious damage on November 26. Then the winds estimated at over 80 miles per hour, blew bricks from some buildings and embedded them in others. Wood beams, separated from buildings, flew through the air and killed hundreds across the south of the country. Towns such as Plymouth, Hull, Cowes, Portsmouth, and Bristol were devastated.

These days, we have advance warnings about potentially dangerous storms heading our way. Of course, the meteorologists aren’t always right on with their predictions, but often they are incredibly accurate. In centuries gone by, it was often the elder men, the ones who had been around a while, who had watched the sky, to see the signs that would give them clues as to coming weather. Unfortunately, on November 14, 1703, any clues they might have seen would not do any good for the people of England. The unusual weather began that day with strong winds from the Atlantic Ocean that battered the southern part of Britain and Wales. The pounding winds damaged many homes and other buildings, but the hurricane-like storm only began doing serious damage on November 26. Then the winds estimated at over 80 miles per hour, blew bricks from some buildings and embedded them in others. Wood beams, separated from buildings, flew through the air and killed hundreds across the south of the country. Towns such as Plymouth, Hull, Cowes, Portsmouth, and Bristol were devastated.

Finally, on November 27, 1703, the storm system finally dissipated over England. For almost two weeks, it had ripped the country nearly to shreds. With its hurricane force winds, the storm killed somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000 people. Hundreds of Royal Navy ships were lost to the storm, the worst in Britain’s history. It was the loss of the 300 Royal Navy ships that really caused the death toll to rise. The ships that were anchored carried some 8,000 sailors. All were lost. Then, the Eddystone Lighthouse, which had been built on a  rock outcropping 14 miles from Plymouth, was blown over by the storm. All of its residents, including its designer, Henry Winstanley, were killed. Huge waves on the Thames River sent water six feet higher than ever before recorded near London. More than 5,000 homes along the river were destroyed.

rock outcropping 14 miles from Plymouth, was blown over by the storm. All of its residents, including its designer, Henry Winstanley, were killed. Huge waves on the Thames River sent water six feet higher than ever before recorded near London. More than 5,000 homes along the river were destroyed.

The author Daniel Defoe, witnessed the storm, and it had such an impact on him that he wrote his first book, entitled “The Storm” the following year. In “The Storm” he described the storm as an “Army of Terror in its furious March.” Sometimes the best inspiration for writing a book is the events of real life. Defoe would later go on to write the well known novel “Robinson Crusoe.”

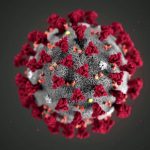

Let’s face it…2020, doesn’t seem to have a lot in it to be thankful for. It has been a tough year in many ways. With Covid-19, quarantines, lock downs, job losses, business losses, election struggles, riots, protests, and homeschooling…by choice or not, things looked pretty grim. Many people have lost loved ones, or friends, or friends and family of friends. Still, we have survived…those of us left, and many of us have contracted Covid-19, and still we have survived. This has been awful, and we will always miss those we have lost, but we Americans are a strong breed. We built this nation on God’s ways, and while some would disagree, that is a fact. Our forefathers came to this country to escape religious persecution, and founded this country on the principle that we should all have freedom to worship as we see fit. They knew that people would disagree on religion, but each person should have the right to choose for themselves.

Let’s face it…2020, doesn’t seem to have a lot in it to be thankful for. It has been a tough year in many ways. With Covid-19, quarantines, lock downs, job losses, business losses, election struggles, riots, protests, and homeschooling…by choice or not, things looked pretty grim. Many people have lost loved ones, or friends, or friends and family of friends. Still, we have survived…those of us left, and many of us have contracted Covid-19, and still we have survived. This has been awful, and we will always miss those we have lost, but we Americans are a strong breed. We built this nation on God’s ways, and while some would disagree, that is a fact. Our forefathers came to this country to escape religious persecution, and founded this country on the principle that we should all have freedom to worship as we see fit. They knew that people would disagree on religion, but each person should have the right to choose for themselves.

This year has tested us in so many ways, but we are Americans, and we don’t give up. We are patriots, and we

love God and country. As we are faced with new challenges, we have a chance to prove once again that we are fighters. We might be down right now, but we aren’t out, and we don’t quit. America is still the land where dreams come true, and it’s because we never give up. This year has been harder than any in my lifetime…maybe harder than any in the lifetimes of most of us, but we have come through it together. That is something to be thankful for, even with all the worry, loss, and fighting. Thanksgiving is a time to think back on the past year, and on our lives, and to be thankful for all we have been given.

love God and country. As we are faced with new challenges, we have a chance to prove once again that we are fighters. We might be down right now, but we aren’t out, and we don’t quit. America is still the land where dreams come true, and it’s because we never give up. This year has been harder than any in my lifetime…maybe harder than any in the lifetimes of most of us, but we have come through it together. That is something to be thankful for, even with all the worry, loss, and fighting. Thanksgiving is a time to think back on the past year, and on our lives, and to be thankful for all we have been given.

This year may have been a really hard one, but our loved ones who have gone on before us, would never want us to give up…or quit. They would want us to live on and be happy. They would want us to be thankful, and to live our lives in such a way as to make them proud. We could have given up this year, but that was never really

an option…now, was it? Thanksgiving is our day to celebrate this land that was founded on our love for God. So whether you are in quarantine, in a city where gathering together is only allowed in small groups, or just far away from your family, remember to take a few minutes to thank God for all we have been given. We are among the most blessed people in the world, and we need to remember that. Happy Thanksgiving everyone!! God bless you all and God bless America!!

an option…now, was it? Thanksgiving is our day to celebrate this land that was founded on our love for God. So whether you are in quarantine, in a city where gathering together is only allowed in small groups, or just far away from your family, remember to take a few minutes to thank God for all we have been given. We are among the most blessed people in the world, and we need to remember that. Happy Thanksgiving everyone!! God bless you all and God bless America!!

America has been the land of opportunity since its inception, and people often worked years to save enough money to pay for passage to what many considered the promised land. It wasn’t cheap, but the money for passage was just the beginning of the grueling process of becoming a citizen of the United States. They knew some of what they would face, but not all. Still, it did not deter them. For a chance at a better life, they came. Many immigrants came through Ellis Island, passing by the Statue of Liberty on their way. It was their first glimpse of what they considered the symbol of America. Then they went on to Ellis Island, where their pre-entry screening began.

America has been the land of opportunity since its inception, and people often worked years to save enough money to pay for passage to what many considered the promised land. It wasn’t cheap, but the money for passage was just the beginning of the grueling process of becoming a citizen of the United States. They knew some of what they would face, but not all. Still, it did not deter them. For a chance at a better life, they came. Many immigrants came through Ellis Island, passing by the Statue of Liberty on their way. It was their first glimpse of what they considered the symbol of America. Then they went on to Ellis Island, where their pre-entry screening began.

First, they were rigorously questioned…what we call vetting today. They asked things like: “Are you meeting a relative here in America? Who? Have you been in a prison, almshouse, or institution for care of the insane? Are you a polygamist? Are you an anarchist? Are you coming to America for a job? Where will you work? Are you  deformed or crippled? Who was the first President of America? What is the Constitution? Which President freed the slaves? Can you name the 13 original Colonies? Who is the current President of the United States?” Providing they passed this first test, they moved on to the next level. Many people these days would take offense at some of these questions…especially the health questions. What they don’t understand is that an unhealthy person or one with a disability could have been a burden to society…even more so than the problems with disabilities today. I know that sounds bad, but they couldn’t afford to take lots of people that the government was going to have to support. They also couldn’t take people with a communicable disease that could cause an epidemic in our country…something we can all understand these days. Every immigrant with a medical condition was marked on their on the shoulder of their clothing with their condition. Things like “PG” for pregnant, “B” for back problems, “SC” for scalp condition, etc. That way, every station down the line knew the problem. Sick children had to be quarantined away from their parents.

deformed or crippled? Who was the first President of America? What is the Constitution? Which President freed the slaves? Can you name the 13 original Colonies? Who is the current President of the United States?” Providing they passed this first test, they moved on to the next level. Many people these days would take offense at some of these questions…especially the health questions. What they don’t understand is that an unhealthy person or one with a disability could have been a burden to society…even more so than the problems with disabilities today. I know that sounds bad, but they couldn’t afford to take lots of people that the government was going to have to support. They also couldn’t take people with a communicable disease that could cause an epidemic in our country…something we can all understand these days. Every immigrant with a medical condition was marked on their on the shoulder of their clothing with their condition. Things like “PG” for pregnant, “B” for back problems, “SC” for scalp condition, etc. That way, every station down the line knew the problem. Sick children had to be quarantined away from their parents.

Sometimes people had to be held at Ellis Island for a time…weeks and even months, until they got well, or could get someone who would agree to sponsor them with their disabilities. That said, another problem or set of problems occurred. There were minimal beds available at any given time, and people spoke different languages, making communication difficult. Often, fights broke out and had to be settled, and sometimes  people had to sleep on the floor. Sometimes, children came over alone. Their parents were dead, and they were sent to live with relatives or maybe to be adopted. Sometimes they were on Ellis Island for months…so long in fact that a playground was build so they could play. A school was started because they needed an education. And sometimes children had to be sent back alone or with a parent if they had one. Some people were rejected. It was part of the process. It was hard…on everyone, but the reward was a better life, if they were accepted. It was tough, and still, they came. They knew it was worth it. The nation has always accepted immigrants. We just expect them to do so legally. The process is difficult, but it is worth it.

people had to sleep on the floor. Sometimes, children came over alone. Their parents were dead, and they were sent to live with relatives or maybe to be adopted. Sometimes they were on Ellis Island for months…so long in fact that a playground was build so they could play. A school was started because they needed an education. And sometimes children had to be sent back alone or with a parent if they had one. Some people were rejected. It was part of the process. It was hard…on everyone, but the reward was a better life, if they were accepted. It was tough, and still, they came. They knew it was worth it. The nation has always accepted immigrants. We just expect them to do so legally. The process is difficult, but it is worth it.

What would the modern farm be without the tractor? People in the 19th century knew exactly what it would be, even if they had no idea what a tractor was. John Froelich was born on November 24, 1849, in Iowa. His life would end up changing much in the agricultural industry. As an adult, Froelich operated a grain elevator and mobile threshing service. His job was to bring a crew to local farms every year at harvest time. He hired a crew and dragged a heavy steam-powered thresher through Iowa and the Dakotas, threshing farmers’ crops for a fee. I suppose it was a good way to make a living, but his machine was bulky, hard to transport, and expensive to use. To top it off, it was also dangerous…one spark from the boiler on a windy day, and he could find the whole prairie ablaze.

What would the modern farm be without the tractor? People in the 19th century knew exactly what it would be, even if they had no idea what a tractor was. John Froelich was born on November 24, 1849, in Iowa. His life would end up changing much in the agricultural industry. As an adult, Froelich operated a grain elevator and mobile threshing service. His job was to bring a crew to local farms every year at harvest time. He hired a crew and dragged a heavy steam-powered thresher through Iowa and the Dakotas, threshing farmers’ crops for a fee. I suppose it was a good way to make a living, but his machine was bulky, hard to transport, and expensive to use. To top it off, it was also dangerous…one spark from the boiler on a windy day, and he could find the whole prairie ablaze.

Froelich knew that this was no way to do business. He decided that he had to try something new. In 1890, instead of that cumbersome, hazardous steam engine, Froelich came up with the idea of a gas powered engine. The size comparison alone made it a far superior choice. So, he and his blacksmith mounted a one-cylinder gasoline engine on his steam engine’s running gear and set off for a nearby field to see if it worked. To their excitement, it did. The tractor  Traveled at a speed of three miles per hour. Of course, that was going to take them a long time to go from one location to another. The real test came when they took their new machine on the road for the annual threshing season. The good news is that the machine was a success there too. The crew threshed more than a thousand bushes of grain every day, 72,000 bushels in all, and they used only 26 gallons of gasoline. Of even greater importance, was that they did the whole thing without one fire.

Traveled at a speed of three miles per hour. Of course, that was going to take them a long time to go from one location to another. The real test came when they took their new machine on the road for the annual threshing season. The good news is that the machine was a success there too. The crew threshed more than a thousand bushes of grain every day, 72,000 bushels in all, and they used only 26 gallons of gasoline. Of even greater importance, was that they did the whole thing without one fire.

It was time to take the project to the next level. Froelich found eight investors, and they formed the Waterloo Gasoline Traction Engine Company. They built four prototype tractors and sold two. Unfortunately, both were soon returned. Rather than lose the company, and to make money, the company branched out into stationary engines. That was somewhat more successful and its first engine powered a printing press at the Waterloo Courier newspaper. Froelich was happy  with the success, but that was really not where his interests were. He was into farming equipment and wanted to make an engine that worked for that. So he left the company in 1895. Froelich might have jumped the gun a little bit, because Waterloo kept working on its tractor designs. The designs still weren’t wildly successful, and between 1896 and 1914, Waterloo sold just 20 tractors in all. Success finally came when in 1914, the company introduced its first Waterloo Boy Model “R” single-speed tractor, which sold very well…118 in 1914 alone. The next year, its two-speed Model “N” was even more successful. In 1918, the John Deere plow-manufacturing company bought Waterloo for $2,350,000.

with the success, but that was really not where his interests were. He was into farming equipment and wanted to make an engine that worked for that. So he left the company in 1895. Froelich might have jumped the gun a little bit, because Waterloo kept working on its tractor designs. The designs still weren’t wildly successful, and between 1896 and 1914, Waterloo sold just 20 tractors in all. Success finally came when in 1914, the company introduced its first Waterloo Boy Model “R” single-speed tractor, which sold very well…118 in 1914 alone. The next year, its two-speed Model “N” was even more successful. In 1918, the John Deere plow-manufacturing company bought Waterloo for $2,350,000.

I liked Mathematics in school and I was pretty good at it, but I can’t say that I had the mind of a great mathematician. As to being able to invent something, or create something of great mathematical value, I don’t know if my mind worked in that direction. The really great inventions take an extraordinary mind…one like that of Gladys Mae West (née Brown), an American mathematician who was known for her contributions to the mathematical modeling of the shape of the Earth, and her work on the development of the satellite geodesy models that were eventually incorporated into the Global Positioning System (GPS). I doubt if anyone alive today can say they don’t know about GPS. It has been a fundamental part of life since 1973, although most of us knew nothing about it then.

I liked Mathematics in school and I was pretty good at it, but I can’t say that I had the mind of a great mathematician. As to being able to invent something, or create something of great mathematical value, I don’t know if my mind worked in that direction. The really great inventions take an extraordinary mind…one like that of Gladys Mae West (née Brown), an American mathematician who was known for her contributions to the mathematical modeling of the shape of the Earth, and her work on the development of the satellite geodesy models that were eventually incorporated into the Global Positioning System (GPS). I doubt if anyone alive today can say they don’t know about GPS. It has been a fundamental part of life since 1973, although most of us knew nothing about it then.

West was born in 1930 in Sutherland, Virginia, south of Richmond. Her family was an African-American farming family in a community of sharecroppers. Her mother worked at a tobacco factory, and her father was a farmer, who also worked for the railroad. West knew she did not want for follow in her parents’ footsteps, and she knew that the only way out was to get a really good education. Family money was not going to be her way to college, so she knew she would need scholarships. Fortunately, the high school she attended gifted the top two students each year with a full-ride scholarship to Virginia State College (University at that time), a historically black public university. West worked hard and graduated in 1948 with the title of valedictorian. With the goal of graduating as one of the top two students behind her, West was a little unsure of just what to do next. She had never given much thought to what she would study…if she got to go to college, but she really had her pick, because she had excelled in all of her courses. Her teachers and counselors encouraged her to major in science or math because of their difficulty. West chose to study mathematics, a normally male dominated subject at her college. She also became a member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority. In 1952, she graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Mathematics. Following her graduation, West taught math and science at Waverly, Virginia for two years. Then returned to VSU to complete her Master of Mathematics degree. She graduated in 1955, and briefly took another teaching position in Martinsville, Virginia.

Her big break came in 1956 when she was hired to work at the Naval Proving Ground located in Dahlgren, Virginia. These days it’s called the Naval Surface Warfare Center. West started her job as the second black woman ever hired and one of only four black employees. West was a programmer in the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division for large-scale computers and a project manager for data-processing systems used in the analysis of satellite data. While she was working there, she was also in the process of earning a second master’s degree in public administration from the University of Oklahoma.

West was dedicated to her work. In the early 1960s, she participated in an award-winning astronomical study that proved the regularity of Pluto’s motion relative to Neptune. She also began to analyze data from satellites, putting together altimeter models of the Earth’s shape. She became project manager for the Seasat radar altimetry project, the first satellite that could remotely sense oceans. West consistently put in extra hours, cutting her team’s processing time in half. This extra time spent, earner her a commendation in 1979.

In the mid-1970s she began working on an IBM computer to deliver increasingly precise calculations to model the shape of the Earth…an ellipsoid with irregularities, known as the geoid. She generated an extremely accurate model which required her to employ complex algorithms to account for variations in gravitational, tidal, and other forces that distort Earth’s shape. West’s data ultimately became the basis for the Global Positioning System (GPS), which we all know about today. She was inducted into the United States Air Force Hall of Fame in 2018. Today, West lives quietly with her husband, Ira. They have 3 children and 7 grandchildren.

Many people have tattoos these days, and the shops that perform their arts for people, have to comply with strict and sanitary working conditions. A tattoo performed in unsanitary conditions can become infected, and cause the loss of limb or even life, if it is not caught in time. The artwork these days is intricate and very elaborate. People can customize their tattoo so as to reflect their own personality. These days a tattoo is something lots of people use to express themselves, but tattoos were not always considered a thing of beauty, and was often forced upon people. Never was this more forced than during the Holocaust against the Jews.

Many people have tattoos these days, and the shops that perform their arts for people, have to comply with strict and sanitary working conditions. A tattoo performed in unsanitary conditions can become infected, and cause the loss of limb or even life, if it is not caught in time. The artwork these days is intricate and very elaborate. People can customize their tattoo so as to reflect their own personality. These days a tattoo is something lots of people use to express themselves, but tattoos were not always considered a thing of beauty, and was often forced upon people. Never was this more forced than during the Holocaust against the Jews.

Maria Ossowski was a Polish member of the Resistance imprisoned in Auschwitz in 1943. So many people did not survive, but those who did have lived to tell the truth about the Final Solution…Hitler’s most evil plot and crimes against humanity. Ossowski later recalled the horrible first few minutes of captivity and the tattooing process in the camp. Those people who did not die on the trains, or who were not herded straight to the gas chambers were herded into what they were told was their washroom. Ossowski says, “It was a huge barrack, with the water running, cold water I must add, from the top, there were men in already prison garb, which we never seen before. We were made to strip, we were made to go in front – each one of us – in front of that man, that man or the other one, they were all standing in the line, and we were shaven – we were shaven – our heads were shaven, our private parts were shaven and we were pushed then under that water. And after a while we were pushed out of it into another part of that big block, where the huge amount of terrible-looking – and already smelling terrible – clothes were prepared for us.”

Then they were given one dress with three-quarter sleeves that was put on over their heads. Once they were dressed, they were herded into another part, where female prisoners were sitting by little tables. Each had a job to do. They were to tattoo numbers on each prisoner’s arm. The tattoo process was not done in sanitary conditions, but it was done with an instrument that basically “wrote” the number into their arm. The instrument cut the skin and pushed ink under the skin. Ballpoint pens were not invented then, but the tool used acted in a

similar way. The process continued until the point and ink formed the shape of a number. Originally a sharp stamp was used, but it was impractical, and so they used the needle and ink method. Those who did receive a tattoo on arrival at Auschwitz might actually be considered “lucky” in that only those deemed fit for work were tattooed. The others were sent off for immediate execution. I doubt anyone who carried this forced tattoo considered it lucky.

similar way. The process continued until the point and ink formed the shape of a number. Originally a sharp stamp was used, but it was impractical, and so they used the needle and ink method. Those who did receive a tattoo on arrival at Auschwitz might actually be considered “lucky” in that only those deemed fit for work were tattooed. The others were sent off for immediate execution. I doubt anyone who carried this forced tattoo considered it lucky.

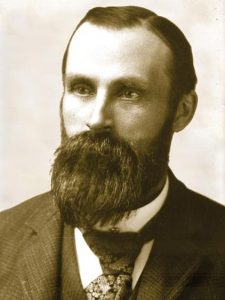

Anyone who has ever been the parent of a premature baby, knows the importance of the incubator. In the mid-1800s and before, a baby born prematurely had almost no chance of survival. Most doctors could only offer comfort care for the infant until death came. All that came to a slow change when a man named Martin Arthur Couney, who was born Michael Cohen in 1869, a Polish advocate and pioneer of neonatal technology, invented the incubator. As time went by, Couney became known as the “Incubator Doctor.”

Anyone who has ever been the parent of a premature baby, knows the importance of the incubator. In the mid-1800s and before, a baby born prematurely had almost no chance of survival. Most doctors could only offer comfort care for the infant until death came. All that came to a slow change when a man named Martin Arthur Couney, who was born Michael Cohen in 1869, a Polish advocate and pioneer of neonatal technology, invented the incubator. As time went by, Couney became known as the “Incubator Doctor.”

While the incubator is an amazing scientific invention, its origins were a little less than what would normally be considered scientific. Prior to Couney’s invention, it was widely believed that premature babies were weaklings, who were unfit to survive into adulthood. It reminds me of what people used to say about orphans. Couney became one of the first advocates for premature babies. Couney allegedly apprenticed under Dr Pierre-Constant Budin, an established French obstetrician in the 1890s, but there is no proof that he ever became a doctor.

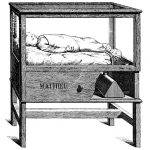

Doctor or not…scientist or not, Couney had a knack for inventing…at least in this instance. He called his invention “The Infantorium” and set about trying to get a doctor to use it, but they would not. Left with no choice, Couney decided to take his invention on the road. Basically, he turned it into an amusement park sideshow, where he gave it the famous name. His plan was to charge visitors 25¢ to view premature babies displayed in the incubators. Now, you might think this whole idea is completely insane, and wonder what doctor…much less parent would give consent for such a crazy idea. I did too. Well, we are both wrong in thinking no one would go along with this. Parents agreed, because their child was considered a lost cause anyway. They were also told that the care given to their children would be free, and if the child survived, they got their baby back. I’m sure is was the hardest decision they ever made, but they felt they had no choice.

Couney is best-known for his Infantorium at Coney Island, New York, although he traveled all around the world before coming to America. The “show” consisted of nurses caring for the children as people watched the process. During Couney’s active years at fairgrounds across America, he and his Infantoriums have become widely accredited with saving the lives of over 6,500 premature babies. Couney is additionally recognized as one of the first pioneers of neonatological technology. He was so well known that people sought him out. “One day, an on-edge young man with the hatbox wanted to see Dr. Couney on a personal matter, he said. The doctor assumed he had something to sell and sent him away. The man took his hatbox and left to spend hours wandering amid the dancing elephants, scenic railways, and carnival din of Coney Island. At last he reappeared; could Dr. Couney see him now? This time Couney said yes. The man opened the hatbox. Inside was a premature baby, tiny and red and struggling for breath.”

Dr Martin A Couney knew what to do. In fact, he knew more about “preemies” than anyone else in the United

States. He was the first American to offer specialized treatment for them and could boast, toward the end of his career, that out of 8,000 in his care, 6,500 survived. “I can’t save all the babies,” he said, “but the percentage of loss is not large, and every parent knows I took good care of his baby until God took its soul. I never had a complaint or an investigation.” He was truly a great man. Martin Couney died on March 1, 1950. As a side note, Coney Island, in New York City was named after this amazing man.

States. He was the first American to offer specialized treatment for them and could boast, toward the end of his career, that out of 8,000 in his care, 6,500 survived. “I can’t save all the babies,” he said, “but the percentage of loss is not large, and every parent knows I took good care of his baby until God took its soul. I never had a complaint or an investigation.” He was truly a great man. Martin Couney died on March 1, 1950. As a side note, Coney Island, in New York City was named after this amazing man.