History

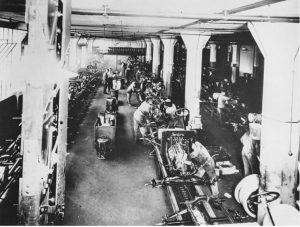

These days, everyone is fighting for a higher minimum wage, but in may years gone by, people were happy to get what little they were given. The Great Depression was one of those times for sure, but there were others. On January 5, 1914, Henry Ford and his vice president James Couzens absolutely stunned the world when they announced that Ford Motor Company would double its workers’ wages to five dollars a day. Now in this day and age, the workers would just go out and look for another job if that was offered, but back then, they were all going to be rich!! Of course, newspapers around the world were gushing with the great news. The notion of a wealthy industrialist sharing profits with workers on such a scale was unprecedented. Everyone wanted to work for Ford.

These days, everyone is fighting for a higher minimum wage, but in may years gone by, people were happy to get what little they were given. The Great Depression was one of those times for sure, but there were others. On January 5, 1914, Henry Ford and his vice president James Couzens absolutely stunned the world when they announced that Ford Motor Company would double its workers’ wages to five dollars a day. Now in this day and age, the workers would just go out and look for another job if that was offered, but back then, they were all going to be rich!! Of course, newspapers around the world were gushing with the great news. The notion of a wealthy industrialist sharing profits with workers on such a scale was unprecedented. Everyone wanted to work for Ford.

In the century since, many people have theorized that the increased pay was to justify assembly line speed-ups, while others speculated it was to counteract high labor turnover due to increasingly monotonous assembly line work. Those who were fans of Ford called it pure philanthropy. Those who didn’t like Ford called it little more than an elaborate publicity stunt…maybe to gain fame or to brag about his successes, but the truth was likely a little of both. A successful boss should share his successes with those who helped him to achieve the level of success he has gained. Of course, not all do, and my guess is that those who wouldn’t do that are the ones who screamed the loudest. There is no pain in business bigger that when someone does the right thing when you won’t.

In order to really understand why Ford implemented the Five-Dollar Day, one must realize that his advances in the moving assembly line, and experiments through 1913 and into 1914 reduced the time required to build a Model T automobile from 12½ hours to just 93 minutes. Increased efficiencies lowered production costs, which lowered customer prices, which increased demand. The public was eager to buy all of the cars Ford could build. That meant that he needed to increase production, and good help is always hard to find. When you find good workers, you should pay them well. Explosive production gains came at the cost of worker satisfaction. The workers were skilled in their little area of the project, and after a while, doing the same job over and over again can get monotonous. The very goal of the moving assembly line was to take what had been relatively skilled craftwork and reduce it to simple, rote tasks. Workers who had previously taken pride in their skilled labor were quickly bored, and some took to lateness and absenteeism. Many simply quit, and Ford found itself with a crippling labor turnover rate of 370 percent. The assembly line was a great invention, but it was hard on the workers, and the assembly line depended on a steady crew to run it. Training replacements was expensive and time consuming, so Ford decided that a bigger paychecks might make the factory’s tedious labor more tolerable.

The increased wages may have seemed like the best solution, but it backfired in a way. The need to retain workers and the subsequent Five-Dollar Day as an effort to do so, worked too well in the end. Within days of the announcement, thousands of applicants came to Detroit from all over the Midwest. They parked at Ford’s gate, and immediately overwhelmed the company. Riots broke out, and the crowds were turned away with fire hoses in the icy January weather. To overcome the problem, Ford announced that it would only hire workers who had lived in Detroit for at least six months. Finally, the rioting stopped and peace returned to the area. Of course, for those who had jobs at Ford, there was the “fine print” to deal with If you made $2.30 a day under the old pay schedule, for example, you still made that wage under the Five-Dollar plan, but if you met all of the company’s requirements, Ford gave you a bonus of $2.70. I don’t suppose that garnered a lot of good feelings either. Many people couldn’t wrap their minds around the profit-sharing plan. They needed the money now.

Part of Henry Ford’s reasoning behind the Five-Dollar Day was that workers who were troubled by money problems at home would be distracted on the job. If higher pay was intended to eliminate these problems, then Ford would make sure that his employees were using his gift “properly.” The company established a Sociological Department to monitor its employees’ habits beyond the workplace. “To qualify for the pay increase, workers had to abstain from alcohol, not physically abuse their families, not take in boarders, keep their homes clean, and contribute regularly to a savings account. Moral righteousness and prudent saving were all well and good, but they were not generally an employer’s business…at least not outside of working hours. In contrast, Ford Motor Company inspectors came to workers’ homes, asked probing questions, and observed general living conditions. If ‘violations’ were discovered, the inspectors offered advice and pointed the families to resources

offered through the company. Not until these problems were corrected did the employee receive his full bonus.” At this point, I would have to say that the company was taking far too much control. Many others agreed, and by 1921, the Sociological Department was largely dissolved. The Five-Dollar Day was a good idea in the beginning, but in the end, it was one that just got a little out of control.

offered through the company. Not until these problems were corrected did the employee receive his full bonus.” At this point, I would have to say that the company was taking far too much control. Many others agreed, and by 1921, the Sociological Department was largely dissolved. The Five-Dollar Day was a good idea in the beginning, but in the end, it was one that just got a little out of control.

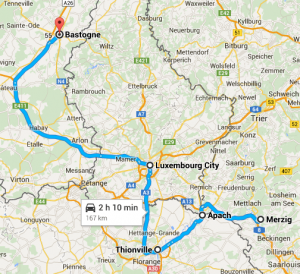

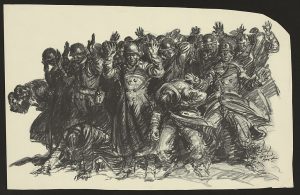

The Battle of the Bulge has been a brutal, hard-fought battle. The soldiers were tired, cold, and hungry; and all they wanted was a night off to recharge. That was not to be. They had more pressing matters to attend to, and the fate of the free world might just depend on their success. The Germans had achieved a total surprise attack on the Belgian town of Bastogne, on the morning of December 16, 1944, due to a combination of Allied overconfidence, preoccupation with Allied offensive plans, and poor aerial reconnaissance because to bad weather. The American forces, specifically the US 101st Airborne Division bore the brunt of the attack and incurred their highest casualties of any operation during the war. The town was vital to the Germans, because it would open up a valuable pathway further north for German expansion. The siege had to be stopped, and the 101st Airborne Division needed help to do it.

The Battle of the Bulge has been a brutal, hard-fought battle. The soldiers were tired, cold, and hungry; and all they wanted was a night off to recharge. That was not to be. They had more pressing matters to attend to, and the fate of the free world might just depend on their success. The Germans had achieved a total surprise attack on the Belgian town of Bastogne, on the morning of December 16, 1944, due to a combination of Allied overconfidence, preoccupation with Allied offensive plans, and poor aerial reconnaissance because to bad weather. The American forces, specifically the US 101st Airborne Division bore the brunt of the attack and incurred their highest casualties of any operation during the war. The town was vital to the Germans, because it would open up a valuable pathway further north for German expansion. The siege had to be stopped, and the 101st Airborne Division needed help to do it.

The capture of Bastogne was the ultimate goal of the Battle of the Bulge…the German offensive through the Ardennes forest. Bastogne provided a road junction in rough terrain where few roads existed. The Belgian town was defended by the US 101st Airborne Division, which had to be reinforced by troops who straggled in from other battlefields. Food, medical supplies, and other resources eroded as bad weather and relentless German assaults threatened the Americans’ ability to hold out. Nevertheless, Brigadier General Anthony C MacAuliffe met a German surrender demand with a typewritten response of a single word, “Nuts.”

This was as bad as it gets, and they needed a hero. Enter “Old Blood and Guts” Patton. General George S Patton Jr was a “street fighter” of a general. He knew what it took to win, and he refused to lose. He was the kind of leader any army, and indeed any government needed. Patton made the decision, the only possible decision he could make. The plan was a “complex and quick-witted strategy wherein he literally wheeled his 3rd Army a sharp 90° turn in a counterthrust movement.” It sounds like a simple plan, but there is no more risk-laden battlefield maneuver than a 90° turn and then a move across and perpendicular to their own lines of communication. The possibilities of mistakes being make were endless. Still, Patton told his men that lives depended on them, and they needed to be in Bastogne…100 miles away, in five days. Not only that, but the march would be over a mountain pass in frigid temperatures. It seemed an impossible

task, but two days later, Patton broke through the German lines and entered Bastogne, relieving the valiant defenders and ultimately pushing the Germans east across the Rhine. I think that if this mission had been asked of any other general, the results might not have been so great. There are generals in war who may annoy everyone around them, but when it comes to doing what is best for the people in trouble, you don’t want anyone else to do the job.

task, but two days later, Patton broke through the German lines and entered Bastogne, relieving the valiant defenders and ultimately pushing the Germans east across the Rhine. I think that if this mission had been asked of any other general, the results might not have been so great. There are generals in war who may annoy everyone around them, but when it comes to doing what is best for the people in trouble, you don’t want anyone else to do the job.

Most of the time, Christmas is a time filled with tradition. Many families celebrate it in exactly the same way every year. Of course, the most important thing about Christmas is the celebration of the birth of Jesus. When I think of where this world would be if Jesus had never come down from Heaven to save us from our own sins, I feel such thankfulness. We needed Him, and He came. No one really knows what day Jesus was born, but in reality, that part doesn’t really matter, but rather the fact that he was born.

Most of the time, Christmas is a time filled with tradition. Many families celebrate it in exactly the same way every year. Of course, the most important thing about Christmas is the celebration of the birth of Jesus. When I think of where this world would be if Jesus had never come down from Heaven to save us from our own sins, I feel such thankfulness. We needed Him, and He came. No one really knows what day Jesus was born, but in reality, that part doesn’t really matter, but rather the fact that he was born.

This Christmas, for many people has been different than any other Christmas we have had before. Most us us weren’t alive in 1918 when the Spanish Flu Pandemic brought quarantine to many places in the world. I don’t know if things were as locked down as they are this year, but those who were ill, could not be with other people, and so their families were separated, as many are now. It makes for a Christmas that doesn’t feel like Christmas. Still, we have to remember the reason for the season, and not the things we have lost. John 3:16 says, “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” Without Jesus, we were doomed. With Him we have victory and everlasting life. What a wonderful reason to celebrate His birthday. He is the Savior of the World, and His way is so easy for us to follow.

Like it or not, this Christmas brings us to the beginning of the last week of a horrible year, and one the likes of which many of us hope never to go through again. January of 2020 found us facing the beginning of the pandemic, and by March we were in quarantine, and the economy was shut down. The year got steadily worse until many of us found ourselves

weary, and ready to start a new year. For my family, that has not changed. We are really ready for 2021. Even today was a sad day, but I will tell of that story tomorrow. I believe the new year will be much better, and as bad as 2020 has been, I am very optimistic for the new year, not for any political or human reason, but because I believe that God is good to us and because he sent His son to die for us, He will not leave us without hope. Therefore I will have hope for 2021. Merry Christmas to all!!

weary, and ready to start a new year. For my family, that has not changed. We are really ready for 2021. Even today was a sad day, but I will tell of that story tomorrow. I believe the new year will be much better, and as bad as 2020 has been, I am very optimistic for the new year, not for any political or human reason, but because I believe that God is good to us and because he sent His son to die for us, He will not leave us without hope. Therefore I will have hope for 2021. Merry Christmas to all!!

Many people know about the Christmas truce of 1914, when in World War I, thousands of British, French, and German troops, exhausted from fighting took the night of Christmas Eve to stop fighting, leave their trenches, and meet the enemy forces in what was known as “No Man’s Land” to exchange gifts, food, and stories. For the soldiers, it was a moral boost, but the Generals disagreed, and determined to prevent further fraternization in the future, saw to it that such activities would be severely punished, thereby ending future Christmas truces for the rest of that war, or the following war. I suppose the Christmas “truce” would have been better called a “cease fire” since they weren’t supposed to fraternize.

Many people know about the Christmas truce of 1914, when in World War I, thousands of British, French, and German troops, exhausted from fighting took the night of Christmas Eve to stop fighting, leave their trenches, and meet the enemy forces in what was known as “No Man’s Land” to exchange gifts, food, and stories. For the soldiers, it was a moral boost, but the Generals disagreed, and determined to prevent further fraternization in the future, saw to it that such activities would be severely punished, thereby ending future Christmas truces for the rest of that war, or the following war. I suppose the Christmas “truce” would have been better called a “cease fire” since they weren’t supposed to fraternize.

In World War II, of course, there was no such truce called, and the fighting continued without taking notice of the holiday. Nevertheless, in 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge, the generals lost just a little bit of their control over the people, when in defiance of the orders, a small group of unlikely guests made their way to a little cabin in the Hurtgen Forest, for a little Christmas Truce of their own. They could have been in so much trouble had they been found out by superior officers, but at the time it just didn’t seem to matter, or maybe it was their host, one Elisabeth Vincken, who along with her 12 year old son stood up to the soldiers, and held off the battle for a few hours. After their home in Aachen was completely destroyed, Elisabeth and her son, Fritz were sent to their cabin, about four miles from Monschau in the Hurtgen Forest near the Belgian border. Her husband visited them as often as he could, but he needed to work. On that Christmas, Elisabeth and Fritz, had been hoping her husband would arrive to spend Christmas with them, but now they knew it was too late. Their Christmas meal would now have to wait for his arrival. Elisabeth and Fritz were alone in the cabin.

Then, the miracle began. Lost in the snow-covered Ardennes Forest, three American soldiers…one badly wounded, wandered around, trying to find the American lines. These poor men had been walking for three days while the sounds of battle echoed in the hills and valleys all around them. They had now idea who was shooting, so they dared not enter the area. Then, on Christmas Eve, they came upon a small cabin in the woods. They cautiously knocked at the door, hoping that they didn’t get shot. Elisabeth blew out the candles and opened the door to find two enemy American soldiers standing at the door and a third lying in the snow behind them. These men might have been soldiers, but were hardly older than boys. The men were armed and  could have simply pushed their way in, but they hadn’t, so she invited them inside and they carried their wounded comrade into the warm cabin. Elisabeth didn’t speak English and they didn’t speak German, but they managed to communicate in broken French. After she heard their story and saw the wounded soldier, Elisabeth gave up the idea of saving the Christmas meal for when her husband could get there. She started preparing a meal for the men. She sent Fritz to get six potatoes and Hermann the rooster…his stay of execution while they waited for her husband was now rescinded. Hermann had been named after Hermann Goering, the Nazi leader, who Elisabeth didn’t care much for. Maybe killing the rooster would make her feel better.

could have simply pushed their way in, but they hadn’t, so she invited them inside and they carried their wounded comrade into the warm cabin. Elisabeth didn’t speak English and they didn’t speak German, but they managed to communicate in broken French. After she heard their story and saw the wounded soldier, Elisabeth gave up the idea of saving the Christmas meal for when her husband could get there. She started preparing a meal for the men. She sent Fritz to get six potatoes and Hermann the rooster…his stay of execution while they waited for her husband was now rescinded. Hermann had been named after Hermann Goering, the Nazi leader, who Elisabeth didn’t care much for. Maybe killing the rooster would make her feel better.

While Hermann roasted and dinner was being prepared, there was another knock on the door. Fritz went to open it, thinking there might be more lost Americans, but instead there were four armed German soldiers. Seeing the German soldiers, and realizing that she could be killed for harboring the enemy, Elisabeth turned white as a ghost. She quickly pushed past Fritz and stepped outside. There was a corporal and three very young soldiers, who wished her a Merry Christmas, but they were lost and hungry. Knowing she had no choice, Elisabeth told them they were welcome to come into the warmth and eat until the food was all gone, but that there were others inside who they would not consider friends. The reaction she expected came when the corporal asked sharply if there were Americans inside and she said there were three who were lost and cold like they were and one was wounded. The corporal stared hard at her. She had to do something, so she said, “Es ist Heiligabend und hier wird nicht geschossen.” In German, that means, “It is the Holy Night and there will be no shooting here.” She insisted they leave their weapons outside. The men couldn’t believe that this woman was standing up to them in such a way. Nevertheless, the men decided to comply and Elisabeth went inside, demanding the same of the Americans. She took their weapons and put them outside next to the Germans’.

Understandably, the fear and tension in the cabin was high as the Germans and Americans eyed each other warily. Nevertheless, the warmth and smell of roast Hermann and potatoes soon eased the tension, and while the men were still wary, the meal was somewhat cordial. The Germans produced a bottle of wine and a loaf of bread. While Elisabeth tended to the cooking, one of the German soldiers, an ex-medical student, examined the wounded American. In English, he explained that the cold had prevented infection, but the man had lost a lot of blood. He needed food and rest. By the time the meal was ready, the atmosphere in the cabin was more relaxed. Two of the Germans were only sixteen, and the corporal was only 23. As Elisabeth said grace, Fritz  noticed tears in the exhausted soldiers’ eyes…both German and American. The moment had somehow touched them all. The unauthorized and very much unplanned “truce” lasted through the rest of that night, and into the morning. The German corporal looked at the map the Americans had, and pointed out the best way for the men to get back to their lines. He also gave them a compass. The Americans asked if they should instead go to Monschau, but the corporal shook his head and said that the Germans had taken Monschau. Elisabeth returned all their weapons and the enemies shook hands and left the cabin, in opposite directions. Soon they were all out of sight, and the truce was over.

noticed tears in the exhausted soldiers’ eyes…both German and American. The moment had somehow touched them all. The unauthorized and very much unplanned “truce” lasted through the rest of that night, and into the morning. The German corporal looked at the map the Americans had, and pointed out the best way for the men to get back to their lines. He also gave them a compass. The Americans asked if they should instead go to Monschau, but the corporal shook his head and said that the Germans had taken Monschau. Elisabeth returned all their weapons and the enemies shook hands and left the cabin, in opposite directions. Soon they were all out of sight, and the truce was over.

With the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Lothair II in 1137, Henry the Proud was the Welf heir of the patrimony of his deceased father-in-law, and possessor of the crown jewels. I always find that strange. Because Henry the Proud had married the Emperor’s daughter, Gertrude, it was he and not the Emperor’s daughter who became the heir and who possessed the crown jewels. Her name is often not mentioned at all. Still, as most of us know, the wife should never be discounted as being insignificant. She will prove you wrong every time.

With the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Lothair II in 1137, Henry the Proud was the Welf heir of the patrimony of his deceased father-in-law, and possessor of the crown jewels. I always find that strange. Because Henry the Proud had married the Emperor’s daughter, Gertrude, it was he and not the Emperor’s daughter who became the heir and who possessed the crown jewels. Her name is often not mentioned at all. Still, as most of us know, the wife should never be discounted as being insignificant. She will prove you wrong every time.

The Siege of Weinsberg took place in Weinsberg, which is in the modern state of Baden-Württemberg, Germany. At that time, Weinsberg was part of the Holy Roman Empire. As often happens, nations and kingdoms often disagree on matters, and wars ensue. The Siege of Weinsberg was a decisive battle between two dynasties…the Welfs and the Hohenstaufen. For the first time, the Welfs changed their war cry from “Kyrie Eleison” to their party cries. The Hohenstaufen used the ‘Strike for Gibbelins’ war cry. Unlike wars these day, apparently, the war cry was very important. I suppose that it was similar to “Charge!!” It was a necessary command to let everyone know that the moment of truth had arrived. Part of the problem might have been the same one that I found odd…Henry the Proud was the son-in-law, and not the son…meaning that had the daughter not married, someone else would have been made the heir.

Henry was a loyal supporter in the warfare between his father-in-law King Lothair and the Hohenstaufen brothers, Duke Frederick II (who was Henry’s brother-in-law, having been married with his sister Judith) and Conrad, then duke of Franconia and anti-king of Germany. While engaged in this struggle, Henry was also occupied in suppressing an uprising in Bavaria, led by Count Frederick of Bogen, during which both duke and  count sought to establish their own candidates as bishop of Regensburg. After a war of devastation, Count Frederick submitted in 1133, and two years later the Hohenstaufen brothers made their peace with Emperor Lothair. Because of his loyalty, Henry stood as a candidate for emperor when his father-in-law passed. However, the local princes were very much against him, so they elected Conrad III, a Hohenstaufen, in Frankfurt on February 2, 1138.

count sought to establish their own candidates as bishop of Regensburg. After a war of devastation, Count Frederick submitted in 1133, and two years later the Hohenstaufen brothers made their peace with Emperor Lothair. Because of his loyalty, Henry stood as a candidate for emperor when his father-in-law passed. However, the local princes were very much against him, so they elected Conrad III, a Hohenstaufen, in Frankfurt on February 2, 1138.

Conrad III immediately began the process of governing, no matter how improper or illegal his reign was. When Conrad III gave the Duchy of Saxony to Count Albert the Bear, the Saxons rose in defense of their young prince, and Count Welf of Altorf, the brother of Henry the Proud, began the war. The reign of Conrad was illegal. He was not the emperor Lothair II had planned to pass his mantle to. The crowning of this illegal emperor outraged the Welfs, and the immediately retaliated. Conrad III had planned to destroy Weinsberg and imprison its soldiers. Still, he was not completely heartless, and in a kind hearted moment, he suspended the final assault after a surrender was negotiated. Conrad III could not kill the women and children. He told the women of the city that they were to be granted the right to leave with whatever they could carry on their shoulders. He though he was going to let them have enough to set themselves up elsewhere, but he underestimated the women.

I don’t know if the women planned what happened next…they must have, because with one accord, they left their possessions, lifting their husbands and children on their backs, they headed out of town. Of course, it was within the power of the emperor to then kill the women too, but he was honorable. When the emperor, saw what was happening, he actually laughed and accepted the women’s clever trick. He decreed that a king should always stand by his word…and he let them go with their families intact. This story became known as the “Loyal Wives of Weinsberg” (Treue Weiber von Weinsberg). The castle ruins are today known as Weibertreu (“wifely loyalty”) in commemoration of the event. I cant say if the story is true, or a fable, but either way, it speaks to the true love a wife has for her husband.

I don’t know if the women planned what happened next…they must have, because with one accord, they left their possessions, lifting their husbands and children on their backs, they headed out of town. Of course, it was within the power of the emperor to then kill the women too, but he was honorable. When the emperor, saw what was happening, he actually laughed and accepted the women’s clever trick. He decreed that a king should always stand by his word…and he let them go with their families intact. This story became known as the “Loyal Wives of Weinsberg” (Treue Weiber von Weinsberg). The castle ruins are today known as Weibertreu (“wifely loyalty”) in commemoration of the event. I cant say if the story is true, or a fable, but either way, it speaks to the true love a wife has for her husband.

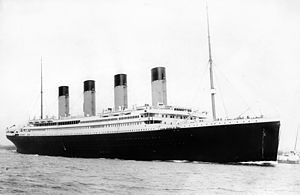

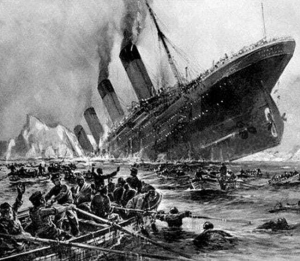

When a ship sinks, the first person to bring up an object from a wreck can claim legal ownership of the wreck under international maritime law. That gives that person the control of the wreck and control over salvage rights. Robert Ballard, one of the men who discovered the Titanic in 1985, had mixed feelings about disturbing the graves of those victims who are still there…a very noble man, if you ask me. Ballard’s partner, Jean-Lous Michel, agreed. They made the decision not to disturb the wreck, but rather to leave it in the pristine (for a wreck) condition that it was in. They didn’t bring up anything from the wreck.

When a ship sinks, the first person to bring up an object from a wreck can claim legal ownership of the wreck under international maritime law. That gives that person the control of the wreck and control over salvage rights. Robert Ballard, one of the men who discovered the Titanic in 1985, had mixed feelings about disturbing the graves of those victims who are still there…a very noble man, if you ask me. Ballard’s partner, Jean-Lous Michel, agreed. They made the decision not to disturb the wreck, but rather to leave it in the pristine (for a wreck) condition that it was in. They didn’t bring up anything from the wreck.

Unfortunately, their act of decency and kindness, left a legal door open, and that has been the greatest source of regret for the two men. Because they chose to bring nothing up from the wreck, they could not claim legal ownership of Titanic. Unfortunately, that left the ship vulnerable, because anyone and everyone now had a legal right for salvage the contents, and even parts of the ship…and they did. The artifacts and ship parts were free for the taking…and they were big business, especially after the movies came out, and interest grew. Soon, Titanic Ventures went in to claim salvage rights, and began bringing up artifacts to sell for exhibits and souvenirs. Since then, they have made a fortune on exhibits all over the world.

Following the find, and subsequent decision not to remove an artifact, anyone with the ability to explore the ocean floor that deep, went in and raided the ship. I’m sure that many of us have seen the Titanic exhibits, me included, and even purchased one of the artifacts, me included, but in my defense, I did not know the thoughts and wishes of Ballard and Michel, or the thoughts and feelings of the families of the deceased, at that time. I looked at the exhibit as a learning tool. I love learning, and I love history, and in fact, one of my own ancestors died on the Titanic, which I suppose gave me as much right to see the exhibit as anyone, but I’m still not sure it is right to make money off of the horrific way others lost their lives.

I remember as I went through the exhibit, walking through the recreation of the steerage rooms, with the eerie sounds of the water on the outside, thinking of the people who had been trapped there on that fateful night. I remember looking at the piece of the hull, thinking that I was standing almost close enough to reach out and touch part of a ship that had been so far under the ocean. I have seen both versions of the Titanic movies, but while looking at the exhibit, it was the original movie that came to my mind. Titanic wasn’t really a love story.  It was a loss story. It was a story of bravery, courage, and yes, love…the kind of love that made a wife refuse to leave her husband and parents to comfort their children, when all hope of survival was lost…holding in the tears of knowing that their children would never get to live their life to adulthood. When I think about all the lives that were lost on that fateful day, I can see how Ballard and Michel would want to leave the Titanic as it was, thereby preserving the graves of all those poor souls. While their idea was noble, it is sad that they didn’t bring at least one thing us so that their ownership and control could remain the gift they had planned to give the families.

It was a loss story. It was a story of bravery, courage, and yes, love…the kind of love that made a wife refuse to leave her husband and parents to comfort their children, when all hope of survival was lost…holding in the tears of knowing that their children would never get to live their life to adulthood. When I think about all the lives that were lost on that fateful day, I can see how Ballard and Michel would want to leave the Titanic as it was, thereby preserving the graves of all those poor souls. While their idea was noble, it is sad that they didn’t bring at least one thing us so that their ownership and control could remain the gift they had planned to give the families.

The many atrocities of the Nazi soldiers are well known, but somehow, every time I read about another one, I am very shocked again. I suppose that the prisoners of war were treated better than the Jews or the political prisoners, but I don’t think it was enough better to really take notice of. The Third Reich was an equal opportunity murder machine. Somehow they felt certain that they could get away with anything they wanted to do.

The many atrocities of the Nazi soldiers are well known, but somehow, every time I read about another one, I am very shocked again. I suppose that the prisoners of war were treated better than the Jews or the political prisoners, but I don’t think it was enough better to really take notice of. The Third Reich was an equal opportunity murder machine. Somehow they felt certain that they could get away with anything they wanted to do.

During the Battle of the Bulge, which was a major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. It took place from December 16, 1944 to January 25, 1945. The battle was launched through the densely forested Ardennes region of Wallonia in eastern Belgium, northeast France, and Luxembourg, towards the end of the war in Europe. The war was winding down, and the Germans knew they were losing. It was during this time that they began trying to get rid of the evidence.

The Malmedy massacre was the result of their attempt to hide what they were doing. I was a war crime committed by members of Kampfgruppe Peiper, which is a part of the SS Division Leibstandarte, a German Waffen-SS unit led by Joachim Peiper, at Baugnez crossroads near Malmedy, Belgium, on December 17, 1944.  In all, 84 American prisoners of war were massacred by their German captors. The Germans assembled the prisoners in a field and mowed them down with machine guns. Afterward, they walked through the field and any of the prisoners who were still alive were killed by close-range shots to the head.

In all, 84 American prisoners of war were massacred by their German captors. The Germans assembled the prisoners in a field and mowed them down with machine guns. Afterward, they walked through the field and any of the prisoners who were still alive were killed by close-range shots to the head.

The term Malmedy massacre has also been generally associated with the series of massacres committed by the same unit on the same day and following days. These men were intent on getting rid of the evidence of their crimes. With these men living, they could tell the world how they had been treated. They felt that the if the men were dead, then Germany could get out of the war crimes. Nevertheless, they killed these men in vain, because the killings were the subject of the Malmedy massacre trial, which was part of the Dachau Trials of 1946.

I am always amazed when a structure stands so long that no one can remember how it came to be. At the southern end of the Appalachian Mountains, there is a small range called the Cohutta Mountains. One mountain in that range is called Fort Mountain. It gets its name from the remnants of a stone formation located on the peak. It has been determined that the structure is ancient, and some sources have indicated that it was possibly built around 400-500 AD, while other sources will not commit to any age. I suppose that the very age of the structure would give good reason as to why it’s origins are unknown.

I am always amazed when a structure stands so long that no one can remember how it came to be. At the southern end of the Appalachian Mountains, there is a small range called the Cohutta Mountains. One mountain in that range is called Fort Mountain. It gets its name from the remnants of a stone formation located on the peak. It has been determined that the structure is ancient, and some sources have indicated that it was possibly built around 400-500 AD, while other sources will not commit to any age. I suppose that the very age of the structure would give good reason as to why it’s origins are unknown.

The zigzagging structure is about 885 feet long, and up to 12 feet thick. It stands up to 7 feet high, but many of the sections are only two to three feet high. The wall, which is scattered with 29 pits, cairns, small cylinders, stone rings, and ruins of a gateway, has stood in its place against all odds. It has stood the test of time, weather, gravity, and even people to continue to stand in its place, high on a mountain peak today.

There are several theories as to who might have built this wall. Some people who found the wall very early on called the structure a fort. They speculated that Hernando de Soto might have built it to defend against the Creek Indians around 1540. This theory was disproven when as early as 1917, when a historian pointed out that de Soto was in the area for less than two weeks. That wouldn’t have been enough time to build a structure that was going to stand the test of time.

There are two other legends floating around that said that the wall was built either by the “Moon-eyed” people according to Cherokee lore or is contributed to a Welsh prince who was said to have made his way to America in 1170. According to Cherokee legend, the “Moon-eyed” people lived in the lower Appalachia region before the  Cherokee came to the area during the late 1700s. The people were said to be called “moon-eyed” because they saw poorly during the day and could see very well at night. It is said that they were small in stature, possibly midgets or dwarfs. The men wore beards, and the people were light-eyed, with very pale white skin. One early historian suggested that they might have been albinos…possibly the ancestors of the Kuna people of Panama, who have a high incidence of albinism.

Cherokee came to the area during the late 1700s. The people were said to be called “moon-eyed” because they saw poorly during the day and could see very well at night. It is said that they were small in stature, possibly midgets or dwarfs. The men wore beards, and the people were light-eyed, with very pale white skin. One early historian suggested that they might have been albinos…possibly the ancestors of the Kuna people of Panama, who have a high incidence of albinism.

It is said that the Cherokee Indians drove them out of the region. Some say that these people built the ancient structures in the area. They thought the structure might have been a temple. The “moon-eyed” people were first mentioned in a 1797 book by Benjamin Smith Barton. Later documentation tells of similar accounts, such as an 1823 book, The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee, which tells of a band of white people who were killed or driven out of Kentucky and West Tennessee. Apparently these people, especially if they were albino, scared the Cherokee. I suppose they might have thought they were evil spirits.

So…who were these “moon-eyed” people? Some say they might be of Welsh descent. There is a story that insists that a prince named Madoc (or Madog) ab Owain Gwynedd, fled his homeland after the death of his father, which had created a Civil War among his seven sons. The sons were supposed to fight to determine who would rule their father’s lands. Now, that is something I can’t imagine. Apparently Madoc did not want to fight, so he set sail with his brother Rhirid and a few followers in 1170 and was said to have landed somewhere around Mobile Bay, Alabama. Later, Madoc returned to his native country and recruited more followers who returned on ten ships to settle in America. After sailing the second time, they were never heard from in Wales again. There are other walls thought to be built by these colonists. A wall near DeSoto Falls, Alabama is nearly identical to the setting, layout, and method of construction of Dolwyddelan Castle in Wales…the birthplace of Madoc. Minor fortifications in the Chattanooga, Tennessee area are also attributed to these Welsh people.

The true answer still lies buried in the past and may never be known. Current legends tell that the sounds of distant drums, flickering lights, and the images of men wearing bearskins have been encountered along the collapsed wall. I find that hard to believe, but I can understand how people can imagine many things. I am just not someone who believes in ghosts. Today, the mysterious peak is part of the Fort Mountain State Park. It’s known for more than the mysterious wall. It is also known for its unique scenery, a mixture of both hardwood and pine forests, as well as, several blueberry thickets. The park contains a beautiful 17 acre mountain lake.

During World War II, transferring intel from the spies in France…the resistance, was difficult. To fly a plane through the anti-aircraft fire was dangerous, and often not successful. To send a spy on foot was not only something that would take far too long, not to mention the possibility of being caught. The intelligence community had to come up with a way to get the information to the generals and to the president quickly…and it had to be a way to succeed without massive loss of life.

During World War II, transferring intel from the spies in France…the resistance, was difficult. To fly a plane through the anti-aircraft fire was dangerous, and often not successful. To send a spy on foot was not only something that would take far too long, not to mention the possibility of being caught. The intelligence community had to come up with a way to get the information to the generals and to the president quickly…and it had to be a way to succeed without massive loss of life.

After much discussion, they happened on the idea of using homing pigeons to take messages back and forth between the spies, the resistance, and even the citizens of France. The idea was to drop the pigeons in a cage that was parachuted into the country. Once the pigeons were on the ground, the people were to write notes on small pieces of paper, place it in the canister attached to the pigeon’s leg, and release the bird to fly home. These pigeons were a huge help to the war effort, and were used in at least two wars.

Years later, a couple stumbled onto a capsule containing a cryptic note dated to either 1910 or 1916. Jade Halaoui was hiking in the fields near Alsace, France this September 2020. Ahead of him, he noticed something shiny. Upon further inspection, he found a small capsule partially buried in the ground and opened it. Inside was a note, written in German in cursive script by a Prussian military officer. Most likely the canister has been attached to a carrier pigeon, but never reached its destination. Halaoui and his partner, Juliette, took the artifact to the Linge Memorial Museum in Orbey.

A curator took a look at the canister and it’s note. He sat down at a table and delicately lifted the frail-looking slip of paper with tweezers. The note was very old, thin, and worn. It was written in spidery German cursive script. It was determined that the message was likely sent by a Prussian infantry officer via carrier pigeon around the onset of World War I. Dominique Jardy, curator at the Linge museum, told one reporter that the note was written in looping handwriting that is difficult to decipher, however, while the date clearly reads July 16…the year could be interpreted as 1910 or 1916. World War I took place between 1914 and 1918. With that in mind, it was concluded that the note was likely written 1916.

Jardy enlisted a German friend to help him translate the note. The note read in part: “Platoon Potthof receives fire as they reach the western border of the parade ground, platoon Potthof takes up fire and retreats after a while. In Fechtwald half a platoon was disabled. Platoon Potthof retreats with heavy losses.” The message, which was addressed to a senior officer. It appears that the infantryman was based in Ingersheim. The note refers to a military training ground, which lead Jardy to think that the note likely refers to a practice maneuver, not actual warfare. If this was the case, and the note was written in 1910, it could refer to a preparation for war. If it was written in 1916, this could have been training in anticipation of a long time of war.

Jardy mentioned that military officials typically sent multiple pigeons with the same message to ensure that crucial information reached its destination. One can only hope that is true, because if this was vital information,

and it did not get through, finding it now is unfortunately more than a century too late. Halaoui discovered the long-lost message just a few hundred yards from its site of origin, so Jardy suspects that this capsule slipped off the homing pigeon’s leg early in its journey. I hope that is true, because some of these pigeons were shot down. Others were caught by the hungry citizens and used for food, but some made it home and they were heroes of war too, because they brought important intel to the Allies.

and it did not get through, finding it now is unfortunately more than a century too late. Halaoui discovered the long-lost message just a few hundred yards from its site of origin, so Jardy suspects that this capsule slipped off the homing pigeon’s leg early in its journey. I hope that is true, because some of these pigeons were shot down. Others were caught by the hungry citizens and used for food, but some made it home and they were heroes of war too, because they brought important intel to the Allies.

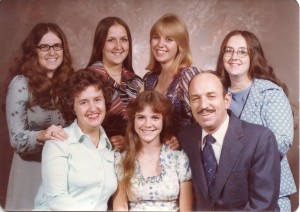

Each year, on the anniversary of my dad, Allen Spencer’s homegoing I am amazed that another year has passed. How can it possibly be 13 years since I last saw my dad? Of course, I know that my parents are in Heaven, and in my future, but that does not lessen the feeling of loneliness and sadness that I feel each day in their absence. I don’t believe anyone ever really gets used to not having their parents in this world with them. Nevertheless, my parents are in Heaven, and each day their is as the first day they went to Heaven. There is always a spirit of celebration and joy in Heaven. There is no better place to be. For that part, I am happy for them, and only sad for me, and for my sisters and our families, all of whom miss my parents very much.

Each year, on the anniversary of my dad, Allen Spencer’s homegoing I am amazed that another year has passed. How can it possibly be 13 years since I last saw my dad? Of course, I know that my parents are in Heaven, and in my future, but that does not lessen the feeling of loneliness and sadness that I feel each day in their absence. I don’t believe anyone ever really gets used to not having their parents in this world with them. Nevertheless, my parents are in Heaven, and each day their is as the first day they went to Heaven. There is always a spirit of celebration and joy in Heaven. There is no better place to be. For that part, I am happy for them, and only sad for me, and for my sisters and our families, all of whom miss my parents very much.

My dad was the spiritual patriarch of our family, always leading us in the way we should go, both in our spiritual life and in our daily physical life. Whenever we had a problem that seemed to big to handle, Dad would sit us down and say, “This is what we are going to do.” We never worried after that, because our dad had stepped up to lead us into God’s victory. He always had a level head in times of turmoil, even if it wasn’t turmoil in our family. We have witnessed so many tragedies in our lifetimes…from national tragedies to personal tragedies, but Dad, and Mom too, showed us that God will never leave us, not forsake us. They were great spiritual leaders for their family, and we are forever grateful for that guidance.

Dad loved to travel, and to show his family this wonderful country. Dad had seen many places in the world during his World War II years of active duty. He has seen places that we will likely never see, but his favorite places were always places in our great nation. Dad loved our country. He was a great patriot, who was loyal to his country unto death. He would never have been disloyal to his country. That was simply not in his nature. He fought too hard for our freedoms, as did all of his fellow soldiers. He would have stood, and did stand in his day, and said “Give me Liberty, or give me death!!” He would have done so, because to lay down and give up was not in his nature. It was through these kinds of teachings that my sisters and I learned how to keep going, to fight and stand for victory. There is not a quitter among us.

I suppose that it is Dad’s teachings we miss the most. He was never harsh. He always taught in love. I remember so many times when I had struggled in school as a grade school student, and I figured I was going to be in so much trouble because of a bad grade. Mom always deferred to Dad. I remember hearing. “Wait until your dad gets home!” Dad was the enforcer of proper education. In reality, I think Mom just thought that where education was concerned, Dad had more patience…and he did. We expected a spanking, and Dad simply said, “Well, we need to work on that.” What a relief. And Dad always did “work” on it with us. When those study

sessions were done…we got it. In the end, we were all good students, and in fact the subjects in which I struggled the most, Math and History, have become my favorites and the ones I most excel at these days, because lets face it, we are still learning. That is because of his love of learning. I will forever miss those study sessions with my dad, just as I miss him in so many other ways, and look forward to seeing him again in Heaven. I love you and Mom, Dad, and I look forward to seeing you both again.

sessions were done…we got it. In the end, we were all good students, and in fact the subjects in which I struggled the most, Math and History, have become my favorites and the ones I most excel at these days, because lets face it, we are still learning. That is because of his love of learning. I will forever miss those study sessions with my dad, just as I miss him in so many other ways, and look forward to seeing him again in Heaven. I love you and Mom, Dad, and I look forward to seeing you both again.