History

During World War II, the Allies used a number of spies, many of them women, but none of them could compare to Virginia Hall, who was considered by the Nazis to be the “most dangerous of all Allied spies.” I can’t think of a greater honor for a spy. It seems to me that the women spies were really the best spies of the war. Maybe it was because they just didn’t expect the women to be spies. That was a big advantage. Virginia Hall had one other thing that made it seem impossible to think of her as a spy…a prosthetic leg, which created a bit of a limp. It was the leg that earned Hall her other name…Limping Lady.

During World War II, the Allies used a number of spies, many of them women, but none of them could compare to Virginia Hall, who was considered by the Nazis to be the “most dangerous of all Allied spies.” I can’t think of a greater honor for a spy. It seems to me that the women spies were really the best spies of the war. Maybe it was because they just didn’t expect the women to be spies. That was a big advantage. Virginia Hall had one other thing that made it seem impossible to think of her as a spy…a prosthetic leg, which created a bit of a limp. It was the leg that earned Hall her other name…Limping Lady.

Born to wealthy parents in Baltimore, Maryland in 1906, Hall was expected to marry well, and become a wife and mother, but she had other plans. Describing herself as “cantankerous and capricious, Hall set her sights on being a diplomat after studying in Paris and falling in love with France, but out of 1500 US diplomats, only 6 were women, and Hall was turned down several times. Still hoping, she took a job as a clerical worker and the US Embassy in Warsaw, Poland. Then tragically, a hunting accident on a trip to Turkey, followed by gangrene infecting the leg, caused it to require amputation, which also disqualified her from the US Foreign Service. It was a crushing blow. She decided to resign from her job and move to Paris in 1939, just as World War II was erupting.

Hall’s life took a dramatic turn on May 10, 1940, when Germany invaded France. Volunteering to drive ambulances for the French army during the six-week long Battle of France, Hall transported wounded soldiers from the front line, while dodging fire from German fighter planes overhead. With the French surrender, Hall traveled to London to support the British war effort there. As she traveled, she impressed an undercover agent who put her in touch with a senior officer in the Special Operations Executive (SOE), which was Winston Churchill’s new secret service. Female operatives were not employed By the SOE, but after six months of failing to infiltrate a single new agent into France, they decided to send Hall to France as the SOE’s first female agent in the country. In the end, she would spend nearly the entire war in France, first as a spy for Britain’s SOE and later for the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Special Operations Branch.

Hall had a bit of a sense of humor, especially when it came to her heavy wooden leg, even nicknaming it Cuthbert. The leg was no obstacle to Hall’s courage either, nor her determination to defeat the Nazis, whom she bitterly hated. Hall used everything at her disposal while undercover in France, and proved herself “exceptionally adept at eluding the Gestapo as she organized resistance groups, masterminded jailbreaks for captured agents, mapped drop zones, reported on German troop movements, set up safe houses, and rescued escaped POWs and downed Allied pilots.” Like many veterans of that era, Even years after the war, Hall rarely talked about her extraordinary career. She attributes the habit to her years as a spy. She once said, “Many of my friends were killed for talking too much.”

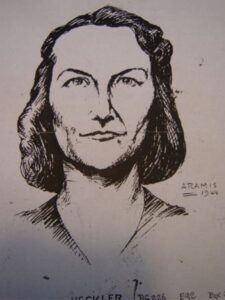

Spy networks were amazingly able to hide in plane site, and when Hall arrived in the Vichy region of France in August 1941, it was under the cover story of being a war correspondent for the New York Post newspaper. Following her arrival in Toulouse, Hall established a resistance network called HECKLER, which gathered information about German troop movements and helped downed British pilots escape to safety. Following her work in Toulouse, she traveled to Lyon, where she helped coordinate activities of the French Resistance. Her plans changed when the United States entered the war. As a US citizen, she could be considered a traitor for working for the British spy networks, because the United States had been considered neutral. Hall was forced underground, but continued operating in France for another 14 months. A good spy needs to have a variety of disguises at the disposal, and Hall became adept at changing her appearance on a moment’s notice. She was also known by multiple aliases. She needed to be almost invisible, at least to the enemy. The Germans, at least early in the war, didn’t think that a woman was capable of being a spy. What a serious miscalculation that turned out to be!!

Hall’s extraordinary effectiveness amazed the SOE commanders and helped change their minds about women operating in combat zones. A year after Hall began working undercover, the SOE finally decided to send more female agents into the field. Hall’s abilities paved the way for more women to serve their countries in this important capacity. It also quickly put women spies, and Hall specifically, on the radar for the Gestapo. Soon, the hunt for “the Limping Lady” was on. They knew only her from a composite sketch, which was to her advantage. Their internal communications declared: “She is the most dangerous of all Allied spies. We must find and destroy her.” Gestapo agents…including notorious investigator Klaus Barbie, who would later be awarded the Iron Cross for torturing and executing thousands of resisters…closing in on her after the Germans seized control of Vichy France in November 1942, Hall was forced to escape to Spain.

To escape France was no easy task. It meant a three day journey on foot in heavy snow across the Pyrenees mountains. The trek was made even more challenging with an 8-pound artificial leg bound to her body with straps and a belt at the waist. At one point, she jokingly mentioned in a message to the SOE that she was concerned that “Cuthbert” would cause problems during her escape. In a funny twist, the receiver of the message didn’t recognize the nickname she used for her prosthetic. SOE headquarters responded, “If Cuthbert is giving you difficulty, have him eliminated.” In the end, it wasn’t “Cuthbert” that caused her problems. When she arrived in Spain, she was arrested and imprisoned for illegally entering the country. Hall was an inmate for six weeks before an inmate being released was able to get word to American officials in Barcelona about her presence so they could arrange her release. She finally made it back to London in January 1943, where she was quietly made a honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire.

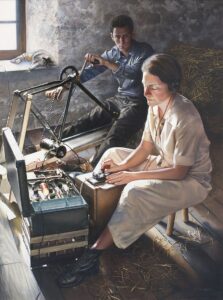

Following her imprisonment, the SOE refused to send her back to France, because they thought was too dangerous with her high profile. That decision was unacceptable to Hall, who decided to join the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which was just establishing their own intelligence operation in France. The Nazi troops were everywhere by that time, so Hall took even more extreme measures to disguise herself. Among them, a French milkmaid, causing her to need to have a rather scary dentist grind down her lovely, white American teeth. In the Haute-Loire region of central France, she disguised herself as an elderly milkmaid and got to work on her radio, coordinating airdrops of arms and supplies for the resistance fighters who were blowing up bridges and sabotaging troop trains, and reporting German troop movements to Allied forces.

Her second tour in France in 1944 and 1945 was even more successful than her first, and at its peak, her network consisted of 1,500 people. With the Germans constantly attempting to track her radio signals, Hall stayed on the move, camping out in barns and attics. As D-Day approached, Hall was operating as a guerrilla leader, and she armed and trained three battalions of French resistance fighters for sabotage missions that helped paved the way for the Allied invasion. One of her many radio reports shows the breadth of her missions. She stated that her team had destroyed four bridges, derailed freight trains, severed a key rail line, and downed telephone lines. By the war’s end, Hall had spent over three full years operating undercover behind enemy lines and, in the words of an official British government report at the end of the war, she was “amazingly successful.”

After the war, when the OSS was dissolved, it became the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Hall became an intelligence analyst. For her wartime service, she was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palme by France and became the only civilian woman during WWII to be awarded a Distinguished Service Cross by the US, which recognizes exceptional valor and risk of life in combat. President Harry Truman wanted to have a public ceremony for the presentation of the medal, but Hall requested a private ceremony instead, saying that she was “still operational and most anxious to get busy.” Hall worked at the CIA until she retired in 1966 and took

quiet pride in her service to her country, although she always maintained a wry sense of humor about it. Her response to receiving the Distinguished Service Cross was, “Not bad for a girl from Baltimore.”

quiet pride in her service to her country, although she always maintained a wry sense of humor about it. Her response to receiving the Distinguished Service Cross was, “Not bad for a girl from Baltimore.”

While in Haute-Loire, Hall had met and fallen in love with an OSS lieutenant, Paul Goillot, who worked for her. In 1957, the couple married after living together off-and-on for years. Hall went on to head the CIA. The other four heads were men. Hall was code named Marie and Diane, but the Germans gave her the nickname Artemis, and the Gestapo reportedly considered her “the most dangerous of all Allied spies.” Because of her artificial foot, she was also known as “the limping lady.” She died on July 8, 1982 at the age of 76 in Barnesville, Maryland.

The “almost” ghost town of Bushong, Kansas got its start in 1886 when the Missouri Pacific Railroad built its tracks across Northern Lyon County. The railroad station was named Weeks, as was the town at first, after Joseph Weeks, who donated 20 acres of land to the railroad. After the railroad built on part of the acreage, it sold some of the acreage as town lots. Although there was no town company, per se, Joseph Weeks also platted another 20 acres and sold lots on that, and a town was born. The Missouri Pacific Railroad also built a large tank pond one mile east of town to supply the steam engines with water, as they pulled their trains over the hills to Council Grove. There were large pastures filled with cattle in the area, and cattle pens were constructed to hold the cattle for shipping. The railroad also bought a valuable stone quarry south of Bushong and shipped quarried rock to Kansas City, about an hour and a half to their Northeast.

The “almost” ghost town of Bushong, Kansas got its start in 1886 when the Missouri Pacific Railroad built its tracks across Northern Lyon County. The railroad station was named Weeks, as was the town at first, after Joseph Weeks, who donated 20 acres of land to the railroad. After the railroad built on part of the acreage, it sold some of the acreage as town lots. Although there was no town company, per se, Joseph Weeks also platted another 20 acres and sold lots on that, and a town was born. The Missouri Pacific Railroad also built a large tank pond one mile east of town to supply the steam engines with water, as they pulled their trains over the hills to Council Grove. There were large pastures filled with cattle in the area, and cattle pens were constructed to hold the cattle for shipping. The railroad also bought a valuable stone quarry south of Bushong and shipped quarried rock to Kansas City, about an hour and a half to their Northeast.

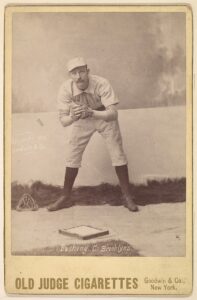

As the town grew, more buildings were needed. The first school building was erected in 1886. The school was a two-story wood-frame structure, and it housed grades 1-8. The school was used until 1948. Then, students were moved to the brick high school building, and the old school building was sold and removed. When the new settlement gained a post office on January 31, 1887, the name was changed to Bushong in honor of Al “Doc” Bushong, who was a baseball player for the Saint Louis Browns. The player’s greatest success came when he was the starting catcher in the 1886 World Series. The Saint Louis Browns of the American Association beat the Chicago White Stockings of the National League. The team owner wanted to do something special for his team to mark their success. Somehow, he made the arrangements for each player to have a town named after them. While all the players had towns named after them, Bushong is the only town that still carries the name of the player they were to have honored. In 1887, Bushong had a population of about 75 people. The first station agent was R D Cottrell, who also built the Bushong Hotel, which he operated with his wife until his death, then she remarried and continued to operate the hotel for a few more years. Other early businesses included a general store, a flour mill, blacksmith, lumber yard, boarding house, and a hog fence factory.

In the town’s saddest event, twelve members of the population died within 48 hours of each other in February 1894, when a diphtheria epidemic gripped the town. It was the last great pandemic of the 19th century, and among the deadliest pandemics in history. The worst effects of the pandemic took place from October  1889 to December 1890, with recurrences in March to June 1891, November 1891 to June 1892, winter of 1893–1894, and early 1895. At the same time, the school in Bushong was closed. The towns first and only doctor, Chester L Stocks, set up his practice in 1896. He was also a druggist, and he continued to serve the community until 1934.

1889 to December 1890, with recurrences in March to June 1891, November 1891 to June 1892, winter of 1893–1894, and early 1895. At the same time, the school in Bushong was closed. The towns first and only doctor, Chester L Stocks, set up his practice in 1896. He was also a druggist, and he continued to serve the community until 1934.

For a brief time in 1899, the town boasted a newspaper called the Bushong Bulletin. It was a small town, and really, how much news could there be. A Methodist church was established that year. It had one large room with a pot-bellied stove in the center and an organ. By 1910, Bushong was a thriving town with a population of 250. The post office even had one rural route. The town also had a number of general stores, a hotel, public school, telegraph, telephone, and express service, and its railroad was providing a considerable amount of shipping. For many years trains stopped at Bushong for passengers. When passenger service was discontinued, trains could still be stopped by “flagging” them down to load freight or livestock. It finally became necessary to establish the Bushong Rural High School, and classes were held in the upper room of the grade school in 1913. Later, students were taught in other town buildings, with the first graduation taking place in 1916. The town also became home to The Bushong State Bank, which was chartered in 1916, but like many other banks, it failed during the Great Depression and closed in 1932. A new brick High School was erected in 1918 consisting of four rooms. Later additions were made, including a gymnasium in 1926. Unfortunately, a fire in the 1920s destroyed a large portion of the downtown area, and the buildings were never rebuilt. In 1923 a new Methodist church building was erected on the same site as the first one. The building utilized the bell from the old church in the belfry. That year, the town’s population was 150. However, the next year, severe drought and heat caused many settlers to move from the area. Bushong was incorporated in 1927, and L A Grimsley was elected as the first mayor. At that time, the town had a population of about 150 and continued to maintain its two room grade school and a four-room rural high school. The Methodist Church and Sunday School were well attended. At about that same time, electricity was approved, and in 1936 Bushong voted to sell their utility to Kansas Electric Company of Emporia. Bushong’s early telephone system was part of the Farmers Mutual Telephone Association, a cooperative company that everyone helped to construct and care for lines and poles. The telephone company was sold in 1960. Like numerous other communities, Bushong was hit hard by the Great Depression and never recovered.

In 1955, school enrollment had dropped to such a degree that Bushong consolidated with the other area schools. High school pupils went to nearby Allen until Northern Heights opened in the fall of 1957, consolidating the high schools of Bushong, Allen, Admire, and Miller. Grade school continued at Bushong until 1966 when all area 3rd and 4th graders went to Bushong and the other grades to Allen and Admire. The school finally closed  in 1970, and the city purchased the building for use as a Civic Center. Currently, the building is abandoned. The railroad discontinued the depot in 1957, and later the depot building was torn down.

in 1970, and the city purchased the building for use as a Civic Center. Currently, the building is abandoned. The railroad discontinued the depot in 1957, and later the depot building was torn down.

During the Cold War, Bushong was again in the spotlight. I became the location of one of the first generations of nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles. One of several Atlas class missile silos developed in the Midwest, active from 1961-1965, was part of the 548th Strategic Missile Squadron was located in the small town. Unfortunately, that was still not enough to save the town from virtual extinction. Bushong’s post office closed on July 2, 1976. Today, Bushong is called home to only about 30 people with no open businesses. The old community is located about 20 miles northwest of Emporia. It’s strange how things work out. What starts out as a thriving town, sometimes gives way to a ghost town, while other times, the town grows to greatness.

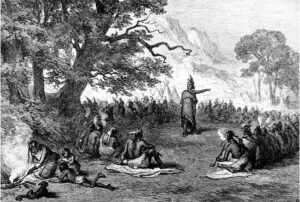

The pilgrims were not the only people who did not like, or accept, British rule. When the French sold some of their territory to the British, the Indian tribes in these areas were not happy about the new regime. The French had more or less left them alone to do as they chose, and so they tended to live in relative peace, but the British were a different kind of rule, and the Indians felt that they were far less conciliatory than their predecessors. It wasn’t that the French and the Indians got along well, after all they had just ended the French and Indian Wars in the early 1760s. It was simply that the British were more demanding and less giving in the area of the Indian rights, than the French had been.

The pilgrims were not the only people who did not like, or accept, British rule. When the French sold some of their territory to the British, the Indian tribes in these areas were not happy about the new regime. The French had more or less left them alone to do as they chose, and so they tended to live in relative peace, but the British were a different kind of rule, and the Indians felt that they were far less conciliatory than their predecessors. It wasn’t that the French and the Indians got along well, after all they had just ended the French and Indian Wars in the early 1760s. It was simply that the British were more demanding and less giving in the area of the Indian rights, than the French had been.

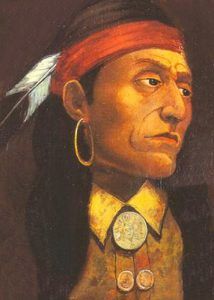

As the matter became more and more heated, an Ottawan Indian chief named Pontiac decided that it was time for the Indian tribes to rebel. So, he called together a confederacy of Native warriors to attack the British force at Detroit. In 1762, Pontiac enlisted support from practically every tribe from Lake Superior to the lower Mississippi for a joint campaign to expel the British from the formerly French-occupied lands. According to Pontiac’s plan, each tribe would seize the nearest fort and then join forces to wipe out the undefended settlements. In April 1763, Pontiac convened a war council on the banks of the Ecorse River near Detroit. It was decided that Pontiac and his warriors would gain access to the British fort at Detroit under the pretense of negotiating a peace treaty, giving them an opportunity to seize forcibly the arsenal there. However, British Major Henry Gladwin learned of the plot, and the British were ready when Pontiac arrived in early May 1763, and Pontiac was forced to begin a siege. His Indian allies in Pennsylvania began a siege of Fort Pitt, while other sympathetic tribes, such as the Delaware, the Shawnees, and the Seneca, prepared to move against various British forts and outposts in Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, at the same time. After failing to take the fort in their initial assault, Pontiac’s forces, made up of Ottawas and reinforced by Wyandots, Ojibwas and Potawatamis, initiated a siege that would stretch into months.

A British relief expedition attacked Pontiac’s camp on July 31, 1763. They suffered heavy losses and were repelled in the Battle of Bloody Run. However, they did succeeded in providing the fort at Detroit with reinforcements and supplies. That victorious battle allowed the fort to hold out against the Indians into the fall. Also holding on were the major forts at Pitt and Niagara, but the united tribes captured eight other fortified posts. At these forts, the garrisons were wiped out, relief expeditions were repulsed, and nearby frontier settlements were destroyed.

Two British armies were sent out in the spring of 1764. One was sent into Pennsylvania and Ohio under Colonel Bouquet, and the other to the Great Lakes under Colonel John Bradstreet. Bouquet’s campaign met with success, and the Delawares and the Shawnees were forced to sue for peace, breaking Pontiac’s alliance. Failing to persuade tribes in the West to join his rebellion, and lacking the hoped-for support from the French, Pontiac finally signed a treaty with the British in 1766. In 1769, he was murdered by a Peoria tribesman while visiting Illinois. His death led to bitter warfare among the tribes, and the Peorias were nearly wiped out.

In a war, good intel is crucial. The opposing armies always use codes in messages so that their plans are not known. Breaking codes is not an easy task, nor is it a quick task. During World War I, the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty was called Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (Old Building) (latterly NID25). The unit was formed in October 1914. It began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the Director of Naval Intelligence, gave intercepts from the German radio station at Nauen, near Berlin, to Director of Naval Education Alfred Ewing, who constructed ciphers as a hobby.

In a war, good intel is crucial. The opposing armies always use codes in messages so that their plans are not known. Breaking codes is not an easy task, nor is it a quick task. During World War I, the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty was called Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (Old Building) (latterly NID25). The unit was formed in October 1914. It began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the Director of Naval Intelligence, gave intercepts from the German radio station at Nauen, near Berlin, to Director of Naval Education Alfred Ewing, who constructed ciphers as a hobby.

Ewing began recruiting civilians such as William Montgomery, who was a translator of theological works from German, and Nigel de Grey, who was a publisher. During the war, the war Room 40 decrypted around 15,000 intercepted German communications from wireless and telegraph traffic. The section’s most notable work was when they intercepted and decoded the Zimmermann Telegram, a secret diplomatic communication issued from the German Foreign Office in January 1917 that proposed a military alliance between Germany and Mexico. This was the most significant intelligence triumph for Britain during World War I, because it played a significant role in drawing the then-neutral United States into the conflict.

Room 40 operations began simply with the acquisition of a captured German naval codebook, the Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM), and maps (containing coded squares) that Britain’s Russian allies had passed on to the Admiralty. Before long it was playing a vital part in the intelligence industry. It all started when the Russians seized this material from the German cruiser SMS Magdeburg after it ran aground off the Estonian coast on August 26, 1914. The Russians recovered three of the four copies that the warship had carried. They retained two and passed the other to the British. In October 1914 the British also obtained the Imperial German Navy’s Handelsschiffsverkehrsbuch (HVB), a codebook used by German naval warships, merchantmen, naval zeppelins and U-Boats. The Royal Australian Navy seized a copy from the Australian-German steamer Hobart on October 11th. Then, on November 30th, a British trawler recovered a safe from the sunken German destroyer S-119, in which was found the Verkehrsbuch (VB), the code used by the Germans to communicate with naval attachés, embassies and warships overseas. It was an amazing find. In March 1915 a British  detachment impounded the luggage of Wilhelm Wassmuss, a German agent in Persia and shipped it, unopened, to London, where the Director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral Sir William Reginald Hall discovered that it contained the German Diplomatic Code Book, Code No. 13040.

detachment impounded the luggage of Wilhelm Wassmuss, a German agent in Persia and shipped it, unopened, to London, where the Director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral Sir William Reginald Hall discovered that it contained the German Diplomatic Code Book, Code No. 13040.

The section retained “Room 40” as its informal name even though it expanded during the war and moved into other offices. Alfred Ewing directed Room 40 until May 1917, when direct control passed to Captain (later Admiral) Reginald ‘Blinker’ Hall, assisted by William Milbourne James. Although Room 40 successfully decrypted Imperial German communications throughout World War I, its function was compromised by the Admiralty’s insistence that all decoded information would only be analyzed by Naval specialists. This meant while Room 40 operators could decrypt the encoded messages they were not permitted to understand or interpret the information themselves. Whatever they couldn’t do, they accomplished a very great deal.

There are places in this world that have hidden places in them that might just surprise most people. At one time, these hidden places might have had a useful purpose, but later their usefulness was gone, and they were either closed up or removed altogether. The Brooklyn Bridge in New York City is one of those places. You can’t really remove a hidden place in a bridge, but you can close the hidden places up if they are no longer needed.

There are places in this world that have hidden places in them that might just surprise most people. At one time, these hidden places might have had a useful purpose, but later their usefulness was gone, and they were either closed up or removed altogether. The Brooklyn Bridge in New York City is one of those places. You can’t really remove a hidden place in a bridge, but you can close the hidden places up if they are no longer needed.

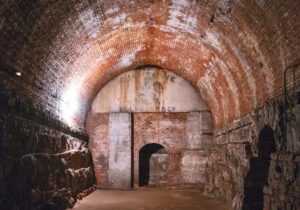

When the Brooklyn Bridge was built, portions of surrounding neighborhoods in Manhattan and Brooklyn had to be demolished in order to build the bridge’s two anchorage sections, which attach the bridge to land. This affected several local merchants more so than others, and because of that impact, the situation had to be addressed. To compensate local merchants and offset some of the bridge’s $15 million budget, wine cellars and other vaulted spaces were incorporated into the bridge’s design. The storage space that had once belonged to the merchants, had to be replaced with useable space, so several wine merchants and other alcohol sellers began renting the spaces in 1883, when the bridge was completed, and except for the Prohibition years, the cellars remained in operation until World War II.

The wine cellars were filled with wine before the Brooklyn Bridge was even operational. The cellars were the idea of bridge engineer John Roebling, and they were completed by his son Washington Roebling after John died. They were created as a solution to an alcohol problem, designed with the hoped that building the cellars would keep the wine dark, cool and secure. The cellars were huge. They are connected by a series of twisting tunnels named after French roads.

Prohibition brought a new era for the cellars. They were turned into newspaper storage areas. When Prohibition

ended, they briefly reopened to the public, but World War II led the city of New York to take over permanent management of the cellars and close them to visitors. Since then, almost no one has seen them. The cellars remain empty and forgotten by the thousands of pedestrians and motorists who cross the Brooklyn Bridge every day. They are used for storage, and an occasional homeless person who finds their way inside.

ended, they briefly reopened to the public, but World War II led the city of New York to take over permanent management of the cellars and close them to visitors. Since then, almost no one has seen them. The cellars remain empty and forgotten by the thousands of pedestrians and motorists who cross the Brooklyn Bridge every day. They are used for storage, and an occasional homeless person who finds their way inside.

We are all used to alternative forms of energy these days. From electric cars to solar heating to wind energy, things have changed some. One thing I had never heard of before, however, is a solar-powered airplane. Of course, the plane was built to promote green energy, and I don’t personally think that green energy is a totally feasible option…sorry if anyone disagrees. Nevertheless, someone came up with the idea of using solar energy for an airplane. I have to admit that the idea of a plane operating totally on solar energy is something that would make me a little apprehensive, nevertheless, one was developed. And it was successful too. A solar-powered airplane completing the 10th leg of it’s journey by landing in Arizona after a 16-hour flight from California in 2015. Now, admittedly, a normal plane could have made the trip in a couple of hours, so in that way, it was rather anticlimactic.

We are all used to alternative forms of energy these days. From electric cars to solar heating to wind energy, things have changed some. One thing I had never heard of before, however, is a solar-powered airplane. Of course, the plane was built to promote green energy, and I don’t personally think that green energy is a totally feasible option…sorry if anyone disagrees. Nevertheless, someone came up with the idea of using solar energy for an airplane. I have to admit that the idea of a plane operating totally on solar energy is something that would make me a little apprehensive, nevertheless, one was developed. And it was successful too. A solar-powered airplane completing the 10th leg of it’s journey by landing in Arizona after a 16-hour flight from California in 2015. Now, admittedly, a normal plane could have made the trip in a couple of hours, so in that way, it was rather anticlimactic.

The plane was the brain-child of Bertrand Piccard, who dreamed of an airplane of perpetual endurance…able to fly day and night without fuel. With the construction of this plane, that dream had been realized, and with the flight of co-founder Andre Borschberg’s flight, history had been made. Still, who has 16 hours to make that flight, when you can drive it in 12 hours. The spindly, single-seat experimental aircraft, dubbed Solar Impulse 2, arrived in Phoenix shortly before 9pm, following a flight from San Francisco that took it over the Mojave  Desert. The solar plane’s pilots were required to take up meditation and hypnosis in training, so they could stay alert for long periods.

Desert. The solar plane’s pilots were required to take up meditation and hypnosis in training, so they could stay alert for long periods.

The plane’s capacity was one…just the pilot in the tiny cockpit. Andre Borschberg, who alternated with fellow pilot Bertrand Piccard at the controls for each segment of what they hope will be the first round-the-world solar-powered flight. “I made it to Phoenix, what an amazing flight over the Mojave desert,” Borschberg said in a Twitter post. Borschberg was the pilot for the Japan-to-Hawaii trip over the Pacific last July, staying airborne for nearly 118 hours…shattering the prior record of 76 hours for a non-stop, solo flight set back in 2006 by the late Steven Fossett in his Virgin Atlantic Global Flyer. Solar Impulse 2 set new duration and distance records for solar-powered flight too.

Not all was picture-perfect with the venture, however. The project was dealt a setback when the Solar Impulse suffered severe battery damage, requiring repairs and testing that grounded it in Hawaii for nine months. After repairs were made, Piccard completed the trans-Pacific crossing, reaching San Francisco after a flight of nearly three days, more than three times the 18 hours Amelia Earhart took to fly solo from Hawaii to California in the 1930s. In many ways, the project would seem to be a failure, but the one real success it had was that the  flights were made without fuel. Its four engines were powered solely by energy collected from more than 17,000 solar cells built into its wings. Surplus power is stored in four batteries during the day, to keep the plane aloft on extreme long-distance flights. The carbon-fiber plane, with a wingspan exceeding that of a Boeing 747 and the weight of a family car, is unlikely to set speed or altitude records. It can climb to 28,000 feet, and cruise at 34 to 62 miles per hour. It’s not something I think I would choose to fly in, but then it’s possible that down the road, when it isn’t an experimental plane, and it can carry more people, I might find myself traveling in just such a plane.

flights were made without fuel. Its four engines were powered solely by energy collected from more than 17,000 solar cells built into its wings. Surplus power is stored in four batteries during the day, to keep the plane aloft on extreme long-distance flights. The carbon-fiber plane, with a wingspan exceeding that of a Boeing 747 and the weight of a family car, is unlikely to set speed or altitude records. It can climb to 28,000 feet, and cruise at 34 to 62 miles per hour. It’s not something I think I would choose to fly in, but then it’s possible that down the road, when it isn’t an experimental plane, and it can carry more people, I might find myself traveling in just such a plane.

As planes became more and more common, it became evident that at some point, they were going to be used commercially. Still, I can’t imagine being on that first commercial flight. I doubt if it comes as a surprised that the first commercial flight in history occurred in the United States. What is surprising is that the flight took place on January 1, 1914, three years before the United States entered World War I. Planes weren’t commonly used forms of transportation in any arena, so a commercial flight is almost beyond imagination. Following that first flight, the Vickers Viscount emerged in 1948, as the first commercial airliner to use turboprop power. That plane was equipped with four Rolls-Royce Dart turboprop engines, the British aircraft had a pressurized cabin and was capable of carrying 40 to 65 passengers.

As planes became more and more common, it became evident that at some point, they were going to be used commercially. Still, I can’t imagine being on that first commercial flight. I doubt if it comes as a surprised that the first commercial flight in history occurred in the United States. What is surprising is that the flight took place on January 1, 1914, three years before the United States entered World War I. Planes weren’t commonly used forms of transportation in any arena, so a commercial flight is almost beyond imagination. Following that first flight, the Vickers Viscount emerged in 1948, as the first commercial airliner to use turboprop power. That plane was equipped with four Rolls-Royce Dart turboprop engines, the British aircraft had a pressurized cabin and was capable of carrying 40 to 65 passengers.

While I would have expected the world’s first commercial jet airliner to follow suit and come from the United States, it did not. The de Havilland DH.106 Comet, the world’s first commercial jet airliner, was actually developed and manufactured by de Havilland at its Hatfield Aerodrome in Hertfordshire, United Kingdom. The Comet 1 prototype first flew in 1949. It featured an aerodynamically clean design with four de Havilland Ghost turbojet engines buried in the wing roots, a pressurized cabin, and large square windows. It’s relatively quiet, comfortable passenger cabin and innovative design, made the plane commercially promising at its debut on this  day, May 2, 1952. Unfortunately, within a year of entering service, the plane began to experience problems. Three Comets were lost within twelve months in highly publicized accidents, after suffering catastrophic in-flight break-ups. Two of the break-ups proved to be caused by structural failure resulting from metal fatigue in the airframe, a phenomenon not fully understood at the time. The third break-up was due to overstressing of the airframe during flight through severe weather. That flight might have had problems even if it had been a more advanced plane, because weather related crashes are still somewhat common today.

day, May 2, 1952. Unfortunately, within a year of entering service, the plane began to experience problems. Three Comets were lost within twelve months in highly publicized accidents, after suffering catastrophic in-flight break-ups. Two of the break-ups proved to be caused by structural failure resulting from metal fatigue in the airframe, a phenomenon not fully understood at the time. The third break-up was due to overstressing of the airframe during flight through severe weather. That flight might have had problems even if it had been a more advanced plane, because weather related crashes are still somewhat common today.

Due the the problems, the Comet was withdrawn from service and extensively tested. Design and construction flaws, including improper riveting and dangerous concentrations of stress around some of the square windows, were ultimately identified as the points of the fatigue. As a result, the Comet was extensively redesigned, with oval windows, structural reinforcements and other changes. Rival manufacturers meanwhile heeded the lessons learned from the Comet while developing their own aircraft. I guess there always has to be that one we learned from. Unfortunately, when people get scared about something, it is very hard to recover in the courts of public opinion.

Sadly, sales of the Comet 1 never fully recovered after the crashes. The improved Comet 2 and the prototype Comet 3 culminated in the redesigned Comet 4 series which debuted in 1958 and did quite well, remaining in commercial service until 1981. Later, the Comet was adapted for military usage. It played a variety of military roles such as VIP, medical and passenger transport, as well as surveillance. In 1997, the last Comet 4 was used as a research platform, making its final flight later that year. The most extensive modification resulted in a specialized maritime patrol derivative, the Hawker Siddeley Nimrod, which remained in service with the Royal Air Force until 2011, over 60 years after the Comet’s first flight.

Sadly, sales of the Comet 1 never fully recovered after the crashes. The improved Comet 2 and the prototype Comet 3 culminated in the redesigned Comet 4 series which debuted in 1958 and did quite well, remaining in commercial service until 1981. Later, the Comet was adapted for military usage. It played a variety of military roles such as VIP, medical and passenger transport, as well as surveillance. In 1997, the last Comet 4 was used as a research platform, making its final flight later that year. The most extensive modification resulted in a specialized maritime patrol derivative, the Hawker Siddeley Nimrod, which remained in service with the Royal Air Force until 2011, over 60 years after the Comet’s first flight.

Some holidays celebrate one thing and one thing only, but others, such as May Day, can have several meanings. When my sisters and I were children, May Day was a special day. Our mom, Collene Spencer would go to the story and buy candy. We made baskets out of construction paper and put candy in them. Then we would sneak around the neighborhood, hang the baskets on the front door of a neighbor and knock on the door. Then, we would run and hide. Sometimes they would catch us, and sometimes they would just yell out “thank you,” but they were always pleased that we though of them and did something nice for them.

Some holidays celebrate one thing and one thing only, but others, such as May Day, can have several meanings. When my sisters and I were children, May Day was a special day. Our mom, Collene Spencer would go to the story and buy candy. We made baskets out of construction paper and put candy in them. Then we would sneak around the neighborhood, hang the baskets on the front door of a neighbor and knock on the door. Then, we would run and hide. Sometimes they would catch us, and sometimes they would just yell out “thank you,” but they were always pleased that we though of them and did something nice for them.

Many people look at May Day as celebrating the beginning of the summer season, or at least the warmer part of Spring. It is a day when it seems like suddenly the flowers have all begun to bloom, the grass gets green, and the trees got their leaves. That is a great way to think about it, because for me Spring and Summer are the best times of the year. I love being able to get out and hike and just enjoy the warm weather. Some of the celebrations included a Maypole dance where ribbons were wrapped around a pole to create a work of art. The ribbons are multi-colored, so its like braiding them together. Its a great game for the kids…and a great welcome to Summer!!

In the United States, May first has another meaning…it is also Law Day. These days it is questionable as to how people  feel about that, but to me it is an important day. Our nation needs law and order, and I believe that most people would agree. Law Day is a day meant to reflect on the role of law in the foundation of the country and to recognize its importance for society. These days there are people who are against the police, except when they need one, and then suddenly the police are very important. I have and have had law enforcement officers in my family, and I can say that they are some of the most caring people I know. So to them I say Happy Law Day!! To everyone else, Happy May Day!!

feel about that, but to me it is an important day. Our nation needs law and order, and I believe that most people would agree. Law Day is a day meant to reflect on the role of law in the foundation of the country and to recognize its importance for society. These days there are people who are against the police, except when they need one, and then suddenly the police are very important. I have and have had law enforcement officers in my family, and I can say that they are some of the most caring people I know. So to them I say Happy Law Day!! To everyone else, Happy May Day!!

Protests are a common story these days, and the police are often kept busy for days trying to keep some kind of order. Not much has really changed in that arena. No nation is exempt from the possibility of violence breaking out because people feel they have been subjected to injustice…whether the facts bear out the belief or not. In 1926, miners across the United Kingdom went on strike. They were being subjected to an involuntary 13% wage cut, as well as an increase in weekly labor, and they were not planning to put up with it. When workers in other industries refused to work in solidarity with the striking miners, it led to a general strike. The work stoppage lasted nine days.

Protests are a common story these days, and the police are often kept busy for days trying to keep some kind of order. Not much has really changed in that arena. No nation is exempt from the possibility of violence breaking out because people feel they have been subjected to injustice…whether the facts bear out the belief or not. In 1926, miners across the United Kingdom went on strike. They were being subjected to an involuntary 13% wage cut, as well as an increase in weekly labor, and they were not planning to put up with it. When workers in other industries refused to work in solidarity with the striking miners, it led to a general strike. The work stoppage lasted nine days.

1926 was an unsettled year, with protests becoming quite common, especially  in London’s Trafalgar Square. As a result of the violence, the police wanted to set up a temporary police station, so they could keep an eye on things. The public would have none of it. Their outcry literally caused the police to drop the project. The problem, however, remained, so they knew that something had to be done. Finally, someone came up with a brilliant idea. That year, they built several large ornate light posts. One of the light posts was configured with the idea of housing what is most likely the world’s tiniest police station. This brilliant idea allowed the police to hide it, and their surveillance, in plain sight.

in London’s Trafalgar Square. As a result of the violence, the police wanted to set up a temporary police station, so they could keep an eye on things. The public would have none of it. Their outcry literally caused the police to drop the project. The problem, however, remained, so they knew that something had to be done. Finally, someone came up with a brilliant idea. That year, they built several large ornate light posts. One of the light posts was configured with the idea of housing what is most likely the world’s tiniest police station. This brilliant idea allowed the police to hide it, and their surveillance, in plain sight.

The police station pole was located inconspicuously at the south-east corner of Trafalgar Square. It is a rather  peculiar and often overlooked world record holder…Britain’s Smallest Police Station. Apparently this tiny box can accommodate up to two prisoners at a time, although its main purpose was to hold a single police officer. I guess you could say that it was a 1920’s version of the ring doorbell camera. It didn’t take video, but the officer inside could clearly watch the square. Once the light fitting was hollowed out, the builders installed a set of narrow windows in order to provide a vista across the main square. Also installed was a direct phone line back to Scotland Yard in case reinforcements were needed in times of trouble. In fact, whenever the police phone was picked up, the ornamental light fitting at the top of the box started to flash, alerting any nearby officers on duty that trouble was near. It was a brilliant idea, but as with all inventions, their usefulness lasts only until the next big thing comes along. Such was the case with the Trafalgar Square Light Pole Police Station. Eventually new technology made the little station obsolete. Today the pole is used for custodial storage.

peculiar and often overlooked world record holder…Britain’s Smallest Police Station. Apparently this tiny box can accommodate up to two prisoners at a time, although its main purpose was to hold a single police officer. I guess you could say that it was a 1920’s version of the ring doorbell camera. It didn’t take video, but the officer inside could clearly watch the square. Once the light fitting was hollowed out, the builders installed a set of narrow windows in order to provide a vista across the main square. Also installed was a direct phone line back to Scotland Yard in case reinforcements were needed in times of trouble. In fact, whenever the police phone was picked up, the ornamental light fitting at the top of the box started to flash, alerting any nearby officers on duty that trouble was near. It was a brilliant idea, but as with all inventions, their usefulness lasts only until the next big thing comes along. Such was the case with the Trafalgar Square Light Pole Police Station. Eventually new technology made the little station obsolete. Today the pole is used for custodial storage.

It seems an impossible task, to keep a disaster a secret, and yet that is exactly what the Soviet Union tried to do when disaster struck on April 26, 1986, at the No. 4 reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, near the city of Pripyat in the north of the Ukrainian SSR. Chernobyl is considered the worst nuclear disaster in history. In terms of cost and casualties, and it is one of only two nuclear energy accidents rated at seven, which is the maximum severity, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The other disaster was the well known 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan that was caused by a tsunami.

It seems an impossible task, to keep a disaster a secret, and yet that is exactly what the Soviet Union tried to do when disaster struck on April 26, 1986, at the No. 4 reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, near the city of Pripyat in the north of the Ukrainian SSR. Chernobyl is considered the worst nuclear disaster in history. In terms of cost and casualties, and it is one of only two nuclear energy accidents rated at seven, which is the maximum severity, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The other disaster was the well known 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan that was caused by a tsunami.

On April 28, 1986, two days after monitoring stations in Sweden, Finland and Norway began reporting sudden high discharges of radioactivity in the atmosphere, the Soviet Union finally broke the news by way of their official news agency, Tass. Two days!! In the realm of nuclear contamination, two days is an eternity!! When the Soviet Union finally told the world, Tass simply said there had been an accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine. They didn’t say they had tried to hide it, but two days of no response tells me they did. The initial emergency response, together with later decontamination of the environment, ultimately involved more than 500,000 personnel and cost an estimated 18 billion Soviet rubles, which is roughly $68 billion US dollars as of the dollar value in 2019.

It was determined that the accident had started during a safety test on an RBMK-type nuclear reactor. During testing a simulation of an electrical power outage was used to help create a safety procedure for maintaining reactor cooling water circulation until the back-up electrical generators could provide power. These units had been tested three times since 1982, but they had failed to provide a solution. On this fourth attempt, an unexpected 10-hour delay meant that an unprepared operating shift was on duty. The power unexpectedly dropped to a near-zero level during the planned decrease of reactor power in preparation for the electrical test. The operators were only able to partially restore the specified test power, putting the reactor in an unstable condition. This risk was not made evident in the operating instructions, so the operators proceeded with the electrical test. Upon test completion, the operators triggered a reactor shutdown, but a combination of unstable conditions and reactor design flaws caused an uncontrolled nuclear chain reaction instead.

The failure caused a large amount of energy to be suddenly released, followed by two explosions that ruptured  the reactor core and destroyed the reactor building. One was a highly destructive steam explosion from the vaporizing superheated cooling water. The other explosion could have been another steam explosion or a small nuclear explosion, like a nuclear fizzle. The explosions were followed immediately by an open-air reactor core fire that released considerable airborne radioactive contamination for about nine days. The contamination fell onto parts of the USSR and western Europe, especially 10 miles away in Belarus, where around 70% landed, before finally being contained on May 4, 1986. In addition to the contamination released by the explosions, the fire gradually released about the same amount of contamination as did the initial explosion. As a result of rising radiation levels in surrounding regions, a 6.2 mile radius exclusion zone was created 36 hours after the accident. About 49,000 people were evacuated from the area, primarily the citizens of Pripyat. Later the exclusion zone was increased to 19 mile radius, and an additional 68,000 people were evacuated from the wider area.

the reactor core and destroyed the reactor building. One was a highly destructive steam explosion from the vaporizing superheated cooling water. The other explosion could have been another steam explosion or a small nuclear explosion, like a nuclear fizzle. The explosions were followed immediately by an open-air reactor core fire that released considerable airborne radioactive contamination for about nine days. The contamination fell onto parts of the USSR and western Europe, especially 10 miles away in Belarus, where around 70% landed, before finally being contained on May 4, 1986. In addition to the contamination released by the explosions, the fire gradually released about the same amount of contamination as did the initial explosion. As a result of rising radiation levels in surrounding regions, a 6.2 mile radius exclusion zone was created 36 hours after the accident. About 49,000 people were evacuated from the area, primarily the citizens of Pripyat. Later the exclusion zone was increased to 19 mile radius, and an additional 68,000 people were evacuated from the wider area.

When the reactor exploded, two of the reactor operating staff lost their lives instantly. Crews rushed to put out the fire, stabilize the reactor, and cleanup the ejected nuclear core. As a result of the disaster and immediate response, 134 station staff and firemen were hospitalized with acute radiation syndrome due to absorbing high doses of ionizing radiation. In the days to months afterward 28 of these 134 people died, and approximately 14 suspected radiation-induced cancer deaths followed within the next 10 years. Significant cleanup operations were taken in the exclusion zone to deal with local fallout, and the exclusion zone was made permanent. The cities in the zone remain abandoned.

By 2011, an excess of 15 childhood thyroid cancer deaths were documented among the wider population. The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) has reviewed all the published research on the incident multiple times, and found that at present, fewer than 100 documented deaths are likely to be attributable to increased exposure to radiation. Of course, there is no way to be sure of that information, because “determining the total eventual number of exposure related deaths is uncertain based on the linear no-threshold model, a contested statistical model, which has also been used in estimates of low level radon and air pollution exposure.” When the expected deaths is viewed in “model predictions with the greatest confidence values of the eventual total death toll in the decades ahead from Chernobyl releases vary, from 4,000 fatalities when solely assessing the three most contaminated former Soviet states, to about 9,000 to 16,000 fatalities when assessing the total continent of Europe. In an effort to reduce the spread of radioactive contamination from the wreckage and protect it from weathering, the protective Chernobyl Nuclear  Power Plant sarcophagus was built by December 1986. It also provided radiological protection for the crews of the undamaged reactors at the site, which continued operating. Due to the continued deterioration of the sarcophagus, it was further enclosed in 2017 by the Chernobyl New Safe Confinement, a larger enclosure that allows the removal of both the sarcophagus and the reactor debris, while containing the radioactive hazard. Nuclear clean-up is scheduled for completion in 2065.” It is my opinion that if they had acted immediately to evacuate the people in surrounding areas, they might have reduced the number of deaths substantially. Keeping the accident a secret for two days was insane, and very likely criminal.

Power Plant sarcophagus was built by December 1986. It also provided radiological protection for the crews of the undamaged reactors at the site, which continued operating. Due to the continued deterioration of the sarcophagus, it was further enclosed in 2017 by the Chernobyl New Safe Confinement, a larger enclosure that allows the removal of both the sarcophagus and the reactor debris, while containing the radioactive hazard. Nuclear clean-up is scheduled for completion in 2065.” It is my opinion that if they had acted immediately to evacuate the people in surrounding areas, they might have reduced the number of deaths substantially. Keeping the accident a secret for two days was insane, and very likely criminal.