History

Sometimes, I am amazed at what you can “sell” people. In 1977, one of Elvis Presley’s assistants saw an opportunity when Elvis didn’t finish a glass of water after a concert. The assistant held an auction and sold the few drops of water left in the glass for $455. And then, there was the two golf balls that were sold for $1400. So, what made these golf balls so special…well, they were swallowed by a python. The snake had to have surgery to remove them, and they were sold after. A British artist, after going through a period of depression, during which she simply stayed in bed, decided to sell the ensuing messy bedroom “furnishings,” so she auctioned them off for $150,000 after calling them “My Bed.” And let us not forget that on March 6, 2012, a woman from Nebraska sold a three-year-old McDonald’s Chicken McNugget for $8100 because it resembled George Washington. She was raising the money to send children to summer camp. The auction site apparently eased its rules on selling expired food for the woman, so that she could raise money to support her cause.

Sometimes, I am amazed at what you can “sell” people. In 1977, one of Elvis Presley’s assistants saw an opportunity when Elvis didn’t finish a glass of water after a concert. The assistant held an auction and sold the few drops of water left in the glass for $455. And then, there was the two golf balls that were sold for $1400. So, what made these golf balls so special…well, they were swallowed by a python. The snake had to have surgery to remove them, and they were sold after. A British artist, after going through a period of depression, during which she simply stayed in bed, decided to sell the ensuing messy bedroom “furnishings,” so she auctioned them off for $150,000 after calling them “My Bed.” And let us not forget that on March 6, 2012, a woman from Nebraska sold a three-year-old McDonald’s Chicken McNugget for $8100 because it resembled George Washington. She was raising the money to send children to summer camp. The auction site apparently eased its rules on selling expired food for the woman, so that she could raise money to support her cause.

Granted these items are novelties, and some went for a good cause, but seriously…people will pay good money  for the strangest things. It actually makes me want to look through my own possessions to see what oddities I might have that would bring in millions of dollars, because apparently, they could sell. You just never know. What is it that makes people decide that they need a few drops of water left in a glass after Elvis drank from the glass, or a McNugget that looks like George Washington, or the many food items that have looked like the Virgin Mary? I suppose that if these things are for a good cause, maybe they are simply donating for the purpose of helping the cause. Or maybe they actually see value in the item or items they are bidding on.

for the strangest things. It actually makes me want to look through my own possessions to see what oddities I might have that would bring in millions of dollars, because apparently, they could sell. You just never know. What is it that makes people decide that they need a few drops of water left in a glass after Elvis drank from the glass, or a McNugget that looks like George Washington, or the many food items that have looked like the Virgin Mary? I suppose that if these things are for a good cause, maybe they are simply donating for the purpose of helping the cause. Or maybe they actually see value in the item or items they are bidding on.

I suppose that in the case of “seeing value” in an item that almost no one else sees value in, I would have to  say…to each his own, but that for the amount some of these items went, there must have been a few people who could see value in something seemingly worthless…at least to me. That said, I decided to go out to an auction site to see what “treasures” I could find. I was somewhat disappointed in that I found no expired food items, or famously worthless celebrity use items. Mostly what I saw were items that did have some value, depending on your need…things like bags full of vintage doll clothes, old pitchers and glassware, belt buckles, automobile emblems, vintage cigarette lighters, coins, and vintage toys. Some of these things could very easily have great value, in that the vintage items could be rare collectables. Nevertheless, I didn’t see anything I couldn’t live without, nor did I find anything that was going for a very high price. I suppose that it would be a rare thing to come across something that cost you nothing, but sold for millions. Still, the idea of selling something for big money isn’t a bad one. It’s just a matter of finding the right item, presenting it to the right audience, and finding yourself feeling very shocked when it sold for the big bucks.

say…to each his own, but that for the amount some of these items went, there must have been a few people who could see value in something seemingly worthless…at least to me. That said, I decided to go out to an auction site to see what “treasures” I could find. I was somewhat disappointed in that I found no expired food items, or famously worthless celebrity use items. Mostly what I saw were items that did have some value, depending on your need…things like bags full of vintage doll clothes, old pitchers and glassware, belt buckles, automobile emblems, vintage cigarette lighters, coins, and vintage toys. Some of these things could very easily have great value, in that the vintage items could be rare collectables. Nevertheless, I didn’t see anything I couldn’t live without, nor did I find anything that was going for a very high price. I suppose that it would be a rare thing to come across something that cost you nothing, but sold for millions. Still, the idea of selling something for big money isn’t a bad one. It’s just a matter of finding the right item, presenting it to the right audience, and finding yourself feeling very shocked when it sold for the big bucks.

A mob of American colonists gathered at the Customs House in Boston, on the cold, snowy night of March 5, 1770. They called themselves Patriots, and they were there to protest the occupation of their city by British troops, who were sent to Boston in 1768 to enforce unpopular taxation measures passed by a British parliament that lacked American representation. I suppose it is possible that the colonists would have agreed to increase their taxes in an effort to help pay for the Seven-Year War, but the reality is that they were not asked…they were told, and it was to be forced upon them. They were not going tolerate that…so they would fight.

A mob of American colonists gathered at the Customs House in Boston, on the cold, snowy night of March 5, 1770. They called themselves Patriots, and they were there to protest the occupation of their city by British troops, who were sent to Boston in 1768 to enforce unpopular taxation measures passed by a British parliament that lacked American representation. I suppose it is possible that the colonists would have agreed to increase their taxes in an effort to help pay for the Seven-Year War, but the reality is that they were not asked…they were told, and it was to be forced upon them. They were not going tolerate that…so they would fight.

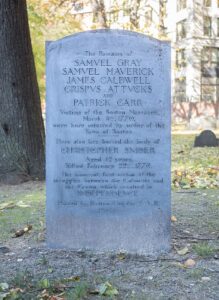

For their part, the British would also not be moved, and they were prepared to fight. British Captain Thomas Preston, the commanding officer at the Customs House, ordered his men to fix their bayonets and join the guard outside the building. The colonists…somewhat less prepared, responded by throwing snowballs and other objects at the British regulars. As the snowball fight commenced, Private Hugh Montgomery was hit, and not knowing what hit him, he discharged his rifle at the crowd. With that, the other soldiers began firing too, and when the smoke cleared, five colonists were dead or dying. They were Crispus Attucks, Patrick Carr, Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick and James Caldwell. Three more were injured. Although it is unclear whether Crispus Attucks, an African American, was the first to fall as is commonly believed, the deaths of the five men are regarded by some historians as the first fatalities in the American Revolutionary War. After the massacre, the British soldiers were put on trial for war crimes. Strangely, patriots John Adams and Josiah Quincy agreed  to defend the soldiers in a show of support of the colonial justice system. When the trial ended in December 1770, two of the British soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter. As punishment, their thumbs were branded with an “M” for murder. In my mind, that is such a minor punishment, for what we view as such a major crime. I’m not sure if I think that any of the British soldiers were really guilty of murder, or even manslaughter, because it seems to me that in a moment of panic, the soldier mistakenly thought he was in eminent danger, when in reality, it was simply a snowball. Still, the punishment really didn’t fit the crime for which it was given.

to defend the soldiers in a show of support of the colonial justice system. When the trial ended in December 1770, two of the British soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter. As punishment, their thumbs were branded with an “M” for murder. In my mind, that is such a minor punishment, for what we view as such a major crime. I’m not sure if I think that any of the British soldiers were really guilty of murder, or even manslaughter, because it seems to me that in a moment of panic, the soldier mistakenly thought he was in eminent danger, when in reality, it was simply a snowball. Still, the punishment really didn’t fit the crime for which it was given.

The Stamp Act was called the “Boston Massacre” by the Sons of Liberty, a Patriot group formed in 1765 to oppose it. The “Boston Massacre” was viewed as a battle for American liberty and just cause for the removal of British troops from Boston. Patriot Paul Revere made an engraving of the incident, depicting the British soldiers lining up like an organized army to suppress an idealized representation of the colonist uprising. Copies of the engraving were distributed throughout the colonies. This was to help reinforce negative American sentiments about British rule. The colonists needed as many in their ranks to be onboard with the battle, and so any depiction of the British as cruel slave masters would help.

The American Revolution officially began in April of 1775, when British troops from Boston fought with American militiamen at the battles of Lexington and Concord. The British troops were under orders to capture  Patriot leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock in Lexington and to confiscate the Patriot arsenal at Concord. Unfortunately for them, the Patriots were several steps ahead of them, and neither of the missions were accomplished because Paul Revere and William Dawes rode ahead of the British to warn Adams and Hancock and to rouse the Patriot minutemen.

Patriot leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock in Lexington and to confiscate the Patriot arsenal at Concord. Unfortunately for them, the Patriots were several steps ahead of them, and neither of the missions were accomplished because Paul Revere and William Dawes rode ahead of the British to warn Adams and Hancock and to rouse the Patriot minutemen.

The British forces were forced to evacuate Boston eleven months later, in March 1776, following American General George Washington’s successful placement of fortifications and cannons on Dorchester Heights. Oddly the eight-year British occupation of Boston ended with a bloodless liberation of the city. General Washington, commander of the Continental Army, was presented with the first medal ever awarded by the Continental Congress for the victory. It would be more than five years before the Revolutionary War came to an end with British General Charles Cornwallis’ surrender to Washington at Yorktown, Virginia.

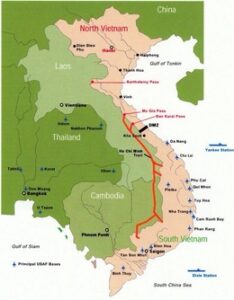

Many people believe that there was no good reason for the war in Vietnam. It seemed like a war we were not going to be allowed to win, and many thought it should have been one we just stayed out of. Vietnam became a French colony in 1877 with the founding of French Indochina, which included Tonkin, Annam, Cochin China and Cambodia…Laos was added in 1893. The French lost control of their colony briefly during World War II, when Japanese troops occupied Vietnam.

Many people believe that there was no good reason for the war in Vietnam. It seemed like a war we were not going to be allowed to win, and many thought it should have been one we just stayed out of. Vietnam became a French colony in 1877 with the founding of French Indochina, which included Tonkin, Annam, Cochin China and Cambodia…Laos was added in 1893. The French lost control of their colony briefly during World War II, when Japanese troops occupied Vietnam.

After the war, Japan and France continued to fight over Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh, a revolutionary leader inspired by Lenin’s Bolshevik Revolution began forming an independence movement. He established the League for the Independence of Vietnam, better known as the Viet Minh, in May of 1941. On September 2, 1945, he declared Vietnam’s independence from France, just hours after Japan’s surrender in World War II. When the French rejected his plan, the Viet Minh resorted to guerilla warfare to fight for an independent Vietnam.

One of the most well-known campaigns of the Vietnam War was codenamed Operation Rolling Thunder. It was an American bombing campaign in which US military aircraft attacked targets throughout North Vietnam from March 1965 to October 1968. This operation was intended to put military pressure on North Vietnam’s communist leaders, thereby reducing their capacity to wage war against the US-supported government of South Vietnam. With that, operation American began its involvement began, not only its assault on North Vietnamese territory, but the expansion of US involvement in the Vietnam War.

By the 1950s, the US military began providing equipment and advisors to help the government of South Vietnam to resist a communist takeover by North Vietnam and its South Vietnam-based allies, the Viet Cong guerrilla fighters. The American military initiated limited air operations within South Vietnam in 1962, in an effort to offer air support to South Vietnamese army forces, destroy suspected Viet Cong bases, and spray herbicides such as Agent Orange to eliminate jungle cover. It was an ugly time for anyone in the area. In August 1964, President Lyndon B Johnson expanded American air operations, when he authorized retaliatory air strikes against North Vietnam following a reported attack on US warships in the Gulf of Tonkin. Later that year, Johnson approved  limited bombing raids on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a network of pathways that connected North Vietnam and South Vietnam by way of neighboring Laos and Cambodia. The president’s goal was to disrupt the flow of manpower and supplies from North Vietnam to its Viet Cong allies. Nothing the United States tried really worked to remove the tensions in the area, and so in 1963, the United States withdrew from Vietnam. Unfortunately, they left behind bombs and land mines from Operation Rolling Thunder and other bombing campaigns of the Vietnam War. By some estimates, those bombs and land mines have killed or injured tens of thousands of Vietnamese people since the United States withdrew its combat troops in 1973.

limited bombing raids on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a network of pathways that connected North Vietnam and South Vietnam by way of neighboring Laos and Cambodia. The president’s goal was to disrupt the flow of manpower and supplies from North Vietnam to its Viet Cong allies. Nothing the United States tried really worked to remove the tensions in the area, and so in 1963, the United States withdrew from Vietnam. Unfortunately, they left behind bombs and land mines from Operation Rolling Thunder and other bombing campaigns of the Vietnam War. By some estimates, those bombs and land mines have killed or injured tens of thousands of Vietnamese people since the United States withdrew its combat troops in 1973.

In 1912, the coal transport ship, Jupiter, was transformed, into the US Navy’s first aircraft carrier. The ship was recommissioned USS Langley (CV-1) and was the first aircraft carrier in history. As aircraft carriers go, we would have laughed about the look of this one. This recreated coal transport ship probably should have just stayed a coal transport, but then we wouldn’t have the aircraft carriers we have today, if Jupiter had not been transformed. It all had to start somewhere.

In 1912, the coal transport ship, Jupiter, was transformed, into the US Navy’s first aircraft carrier. The ship was recommissioned USS Langley (CV-1) and was the first aircraft carrier in history. As aircraft carriers go, we would have laughed about the look of this one. This recreated coal transport ship probably should have just stayed a coal transport, but then we wouldn’t have the aircraft carriers we have today, if Jupiter had not been transformed. It all had to start somewhere.

While USS Langley was the first aircraft carrier made, it was not the first to go down in battle. That “honor” goes to HMS Courageous, on September 17, 1939, only a couple weeks after World War II in Europe began. On that day, German U-boat, U-29, sunk the British aircraft carrier with 2 of the 3 torpedoes fired striking the unfortunate carrier. Courageous went down, taking 519 of her crew with her, thereby becoming the first aircraft carrier ever sunk by a submarine. The US Navy’s first aircraft carrier, the Langley, managed to survive until February 27, 1942, when it was sunk by Japanese warplanes (with a little help from US destroyers), and all of its 32 aircraft are lost.

The USS Langley was originally launched in 1912 as the naval collier (coal transport ship) Jupiter. After World  War I, the Jupiter was converted into the Navy’s first aircraft carrier and rechristened the Langley, after aviation pioneer Samuel Pierpont Langley. Uss Langley was the Navy’s first electrically propelled ship. It was capable of speeds of 15 knots. On October 17, 1922, Lieutenant Virgil C Griffin had the great honor of piloting the first plane, a VE-7-SF, from Langley’s decks. Planes had taken off from ships before, but this was a historic moment. The prestige was short-lived, and after 1937, the Langley lost the forward 40 percent of her flight deck as part of a conversion to seaplane tender, a mobile base for squadrons of patrol bombers.

War I, the Jupiter was converted into the Navy’s first aircraft carrier and rechristened the Langley, after aviation pioneer Samuel Pierpont Langley. Uss Langley was the Navy’s first electrically propelled ship. It was capable of speeds of 15 knots. On October 17, 1922, Lieutenant Virgil C Griffin had the great honor of piloting the first plane, a VE-7-SF, from Langley’s decks. Planes had taken off from ships before, but this was a historic moment. The prestige was short-lived, and after 1937, the Langley lost the forward 40 percent of her flight deck as part of a conversion to seaplane tender, a mobile base for squadrons of patrol bombers.

The Langley was part of the Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines when the Japanese attacked on December 8, 1941. Immediately setting sail for Australia, she arrived on January 1, 1942. On February 22nd, under the command of Robert P McConnell, the Langley, carrying 32 Warhawk fighters, left as part of a convoy to aid the Allies in their battle against the Japanese in the Dutch East Indies. Then, on February 27, the Langley parted company  from the convoy and headed straight for the port at Tjilatjap, Java. About 74 miles south of Java, the carrier met up with two US escort destroyers. Then nine Japanese twin-engine bombers attacked the ship. Although the Langley had requested a fighter escort from Java for cover, none could be spared. She and the escort destroyers were virtually alone. The first two Japanese bomber runs missed their target, as they were flying too high, but the third time around they hit their mark three times. The planes on deck went up in flames. The carrier began to list, and Commander McConnell lost his ability to navigate the ship. In an effort to save his men, McConnell ordered the Langley abandoned, and the escort destroyers were able to take his crew to safety. Of the 300 crewmen, only 16 were lost. The destroyers then sank the Langley before the Japanese were able to capture it. It was necessary that they keep it out of Japanese hands. Better at the bottom of the sea that in the hands of the Japanese.

from the convoy and headed straight for the port at Tjilatjap, Java. About 74 miles south of Java, the carrier met up with two US escort destroyers. Then nine Japanese twin-engine bombers attacked the ship. Although the Langley had requested a fighter escort from Java for cover, none could be spared. She and the escort destroyers were virtually alone. The first two Japanese bomber runs missed their target, as they were flying too high, but the third time around they hit their mark three times. The planes on deck went up in flames. The carrier began to list, and Commander McConnell lost his ability to navigate the ship. In an effort to save his men, McConnell ordered the Langley abandoned, and the escort destroyers were able to take his crew to safety. Of the 300 crewmen, only 16 were lost. The destroyers then sank the Langley before the Japanese were able to capture it. It was necessary that they keep it out of Japanese hands. Better at the bottom of the sea that in the hands of the Japanese.

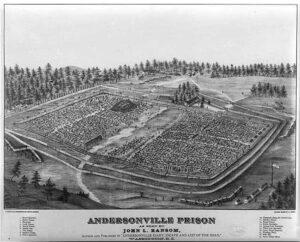

Andersonville POW camp was a Civil War era POW camp that was heavily fortified. It was run by Captain Henry Wirz, who was tried by a military tribunal on charges of war crimes when the war was over. The trial was presided over by Union General Lew Wallace and featured chief Judge Advocate General (JAG) prosecutor Norton Parker Chipman. The prison is located near Andersonville, Georgia, and today is a national historic site that is also known as Camp Sumpter. To me, its design had a somewhat unusual layout in that it had what is called a “Dead Line”. Some people might know what that is, but any prisoner who dared to tough it, much less try to cross it, found out very quickly what it was, because they were shot instantly…no questions asked. For that reason, prisoners rarely escaped from Andersonville Prison. The “dead line” was set up by the Confederate forces guarding the prison, to assist in prisoner control. The prison operated between February 25, 1864, and May 9, 1864. During that time, a total of 4,588 patients visited the Andersonville prison hospital, and 1,026 never left there alive.

Andersonville POW camp was a Civil War era POW camp that was heavily fortified. It was run by Captain Henry Wirz, who was tried by a military tribunal on charges of war crimes when the war was over. The trial was presided over by Union General Lew Wallace and featured chief Judge Advocate General (JAG) prosecutor Norton Parker Chipman. The prison is located near Andersonville, Georgia, and today is a national historic site that is also known as Camp Sumpter. To me, its design had a somewhat unusual layout in that it had what is called a “Dead Line”. Some people might know what that is, but any prisoner who dared to tough it, much less try to cross it, found out very quickly what it was, because they were shot instantly…no questions asked. For that reason, prisoners rarely escaped from Andersonville Prison. The “dead line” was set up by the Confederate forces guarding the prison, to assist in prisoner control. The prison operated between February 25, 1864, and May 9, 1864. During that time, a total of 4,588 patients visited the Andersonville prison hospital, and 1,026 never left there alive.

According to former prisoner, enlisted soldier John Levi Maile, “It consisted of a narrow strip of board nailed to a row of stakes, about four feet high.” The “dead line” completely encircled Andersonville. Soldiers were told to “shoot any prisoner who touches the ‘dead line'” “It was the standing order to the guards,” Maile explained. “A sick prisoner inadvertently placing his hand on the “dead line” for support… or anyone touching it with suicidal intent, would be instantly shot at, the scattering balls usually striking other than the one aimed at.” It was a risk the prisoners took if they chose to be anywhere near the “dead line” at all. Prisoner Prescott Tracy worked as a clerk in the Andersonville hospital. He said, “I have seen one hundred and fifty bodies waiting passage to the “dead house,” to be buried with those who died in hospital. The average of deaths through the earlier months was thirty a day; at the time I left, the average was over one hundred and thirty, and one day the record showed one hundred and forty-six.” The major threats in the prison camp were diarrhea, dysentery, and scurvy.

A sergeant major in the 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, Robert H. Kellogg what he saw when he entered the camp as a prisoner on May 2, 1864, “As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect…stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness. “Can this be hell?” “God protect us!” and all thought that he alone could bring them out alive from so terrible a place. In the center of the whole was a swamp, occupying about three or four acres of the narrowed limits, and a part of this marshy place had been used by the prisoners as a sink, and excrement covered the ground, the scent arising from which was suffocating. The ground allotted to our ninety was near the edge of this plague-spot, and how we were to live through the warm summer weather in the midst of such fearful surroundings, was more than we cared to think of just then.”

After hearing the accounts of men who had the misfortune of being incarcerated in this horrific POW camp, I

wondered if there might have been some changes had the camp been run in more modern times. Of course, there is no guarantee of that, since there has been mistreatment of prisoners-of-war in all wars, and the treatment ultimately falls on the people running the camp and the soldiers monitoring the prisoners. It is, however, a sad state of affairs when prisoners are starved, beaten, frozen, and otherwise mistreated in these camps. The point is to hold them, not murder them.

wondered if there might have been some changes had the camp been run in more modern times. Of course, there is no guarantee of that, since there has been mistreatment of prisoners-of-war in all wars, and the treatment ultimately falls on the people running the camp and the soldiers monitoring the prisoners. It is, however, a sad state of affairs when prisoners are starved, beaten, frozen, and otherwise mistreated in these camps. The point is to hold them, not murder them.

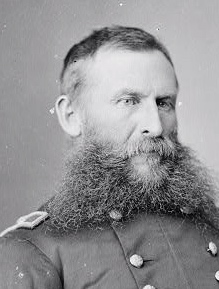

Not every great military hero was at the top of their class at military school. George Crook graduated 38th out of a class of 43 from the United States Military Academy in 1852. Crook was born to Thomas and Elizabeth Matthews Crook on a farm near Taylorsville, Montgomery County, Ohio (near Dayton). While his classroom career was not exemplary, he was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook Nantan Lupan, which means “Chief Wolf.”

Not every great military hero was at the top of their class at military school. George Crook graduated 38th out of a class of 43 from the United States Military Academy in 1852. Crook was born to Thomas and Elizabeth Matthews Crook on a farm near Taylorsville, Montgomery County, Ohio (near Dayton). While his classroom career was not exemplary, he was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook Nantan Lupan, which means “Chief Wolf.”

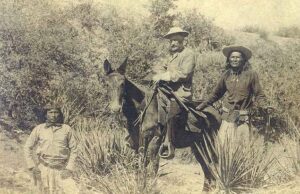

Crook was commissioned in the 4th Infantry and was first stationed in Northern California, until the outbreak of the Civil War. He was appointed colonel of the 36th Ohio Infantry and they were sent immediately to western Virginia, on September 12, 1861. He was promoted to brigadier general on September 7, 1862…less than a year later. He was put in command of a brigade of regiments from Ohio during the battles of South Mountain and Antietam, both part of the Maryland Campaign. Following that campaign, Crook was given command of a cavalry division in the Army of the Cumberland under General George H Thomas. He commanded that division through the Battle of Chickamauga. Crook was sent back to western Virginia and took part in General Ulysses S Grant’s spring campaign in the spring of 1864. During the campaign, Crook successfully commanded his brigade to victory against Confederate General A G Jenkins at the Battle of Cloyd’s Mountain. Crook was given command of the Department of Western Virginia which later became the VIII Corps under General Philip Sheridan, in August of 1864. Crook commanded his men throughout many of the battles of the Valley Campaign of 1864, including the battles of Third Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, and Cedar Creek. Crook was promoted to major general on October 21, 1864 and returned to the command of his department in Cumberland, Maryland. On February 21, 1865, while located in Cumberland Maryland, General Crook along with General Benjamin F Kelley were captured by a group of Confederate partisans under the command of Captain Jesse McNeill. On March 20, 1865, Crook was freed and placed in charge of a division of cavalry in the Army of the Potomac. He commanded his division until the surrender at Appomattox Court House.

Crook fought successful campaigns during the Indian wars, against several tribes, but later went on to speak  out against the unjust treatment of his former Indian adversaries. Crook was considered the Army’s preeminent Indian fighter during the Indian Wars. Even the Indians respected him. He was known to use two Apache scouts, Dutchy and Alchesay in his travels during the Indian Wars as well as his favorite mule, Apache. He died suddenly in Chicago in 1890 while serving as commander of the Military Division of the Missouri. Crook was originally buried in Oakland, Maryland, but in 1898, his remains were transported to Arlington National Cemetery, where he was reinterred. Red Cloud, a war chief of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux), said of him, “He, at least, never lied to us. His words gave us hope.” It was a great tribute.

out against the unjust treatment of his former Indian adversaries. Crook was considered the Army’s preeminent Indian fighter during the Indian Wars. Even the Indians respected him. He was known to use two Apache scouts, Dutchy and Alchesay in his travels during the Indian Wars as well as his favorite mule, Apache. He died suddenly in Chicago in 1890 while serving as commander of the Military Division of the Missouri. Crook was originally buried in Oakland, Maryland, but in 1898, his remains were transported to Arlington National Cemetery, where he was reinterred. Red Cloud, a war chief of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux), said of him, “He, at least, never lied to us. His words gave us hope.” It was a great tribute.

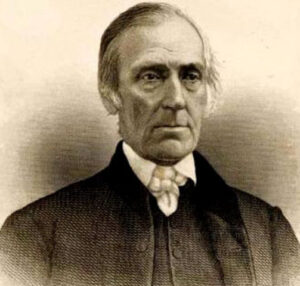

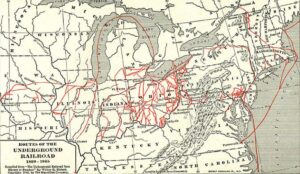

In any kind of slavery situation, there are always people who are willing to help those who are being held against their will. Just like during the Holocaust, when the slaves were in trouble, people came to their rescue by forming the Underground Railroad. One hero of the Underground Railroad was Levi Coffin. In the winter of 1826-1827, fugitives began to come show up at the Coffin house. It started out as a well-kept secret and just a few slaves came, but the numbers increased as it became more widely known on different routes. These slaves were running away from bondage, beatings, and limitless working hours. Their lives were little better than death, and they knew they had to escape or die.

In any kind of slavery situation, there are always people who are willing to help those who are being held against their will. Just like during the Holocaust, when the slaves were in trouble, people came to their rescue by forming the Underground Railroad. One hero of the Underground Railroad was Levi Coffin. In the winter of 1826-1827, fugitives began to come show up at the Coffin house. It started out as a well-kept secret and just a few slaves came, but the numbers increased as it became more widely known on different routes. These slaves were running away from bondage, beatings, and limitless working hours. Their lives were little better than death, and they knew they had to escape or die.

When they arrived at the Coffin house, they were welcomed in and given shelter, they would usually sleep during the day, and then they were quickly forwarded safely on their journey. Neighbors who had been too fearful of the penalty of the law to help at first, saw how well the Underground Railroad was being run and soon they felt encouraged to help. A big part of the change of attitude came from the fearless manner in which Levi Coffin acted and the success his efforts produced. The neighbors began to contribute clothing the fugitives and aid in forwarding them on their way. They were still too afraid to shelter them under their own roof, so that part of the work fell to the Coffin household. There were the “content to watch” people, who obviously wanted to see the work go on…as long as someone else took the risk. And of course, there were those who told Levin Coffin he was wasting his time. They tried to discourage him and dissuade him from running such risks, telling him that they were greatly concerned for my safety and monetary interests. They tried to convince him that continuing this risky business could damage his business and possibly even ruin him. The told him he could be  endangering himself and his family too. I suppose it could have, because there are always those who sympathized with the slave-owners, but Levi Coffin could not stand to see the horrible treatment the slaves endured. He had to do something, no matter what it cost him, just like those who helped the Jews during the Holocaust.

endangering himself and his family too. I suppose it could have, because there are always those who sympathized with the slave-owners, but Levi Coffin could not stand to see the horrible treatment the slaves endured. He had to do something, no matter what it cost him, just like those who helped the Jews during the Holocaust.

Levi listened to these “counselors” and then told them that he “felt no condemnation for anything that I had ever done for the fugitive slaves. If, by doing my duty and endeavoring to fulfill the injunctions of the Bible, I injured my business, then let my business go. As to my safety, my life was in the hands of my Divine Master, and I felt that I had his approval. I had no fear of the danger that seemed to threaten my life or my business. If I was faithful to duty and honest and industrious, I felt that I would be preserved and that I could make enough to support my family.”

Even some of those people who were opposed to slavery, felt it was very wrong to harbor fugitive slaves. They figured that the slaves must be guilty of some crime, such as possibly killing their masters or committed some other crime in their escape attempts…making those who helped them an accomplice to the “crime” they were supposedly guilt of. Oh, they had every imaginable objection, and figured it was, at the very least, their duty to make their thoughts known. Once they had voiced their objections, their conscience was clear, and if Levi met with a tragic end, they could at least say, “I told him!!” Levi, in return asked one such “neighbor’s keeper” neighbor, if he thought the Good Samaritan stopped to inquire whether the man who fell among thieves was guilty of any crime before he attempted to help him? He said, “I asked him if he were to see a stranger who had fallen into the ditch would he not help him out until satisfied that he had committed no atrocious deed?” I suppose it was a “crime” to escape their masters, but then some laws should not be laws, and slavery certainly falls into that category. Levi Coffin had to follow his spirit and do what he felt God would expect of him, and in  the end, he saved many lives.

the end, he saved many lives.

Many of Levi’s pro-slavery customers left him for a time, and sales were down. For while his business struggled, but Levi knew that he was doing God’s will, and so God would take care of him and his business. Before long, new customers replaced those who had left him. New settlements were rapidly forming to the north and Levi’s own was filling up with emigrants from North Carolina and other States. His trade increased and his business grew. He says of this time in his life, “I was blessed in all my efforts and succeeded beyond my expectations.”

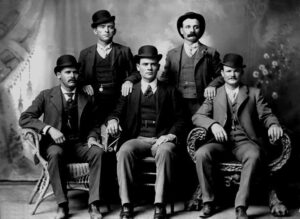

The American cowboy hat. Anyone who knows anything about the Old West knows about the Stetson cowboy hat, and every great cowboy wore them, right? Wrong. The truth is that in the Old West, most men wore a Derby hat. If you’ve seen the movie, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, then you have seen a more realistic picture of the Old West.

The American cowboy hat. Anyone who knows anything about the Old West knows about the Stetson cowboy hat, and every great cowboy wore them, right? Wrong. The truth is that in the Old West, most men wore a Derby hat. If you’ve seen the movie, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, then you have seen a more realistic picture of the Old West.

The myth of the cowboy hat did come about from the hat that was created by John Stetson, and while it was a classic, it didn’t actually come into play until the very end of the 19th century, not the early part like most people think. The Stetson cowboy hat was first introduced in 1865, but it just didn’t take off like John Stetson had hoped. The cowboy hat was based somewhat on a Spanish design, and thr rumor was that a random cowboy saw Stetson’s at and paid him $5.00 for it. After that, it was said to be all the rage.

The truth is vastly different. I don’t know if a cowboy bought that first cowboy hat for $5.00 or not, but while we think that the Derby hat or the top hat were only worn by the bankers, businessmen, or the very rich, that belief is wrong. The early cowboys liked the derby hat best, and those who did not like the Derby usually wore a top hat or a hat associated with their professions, like a conductors cap. The Derby was also known as the Bowler hat, with many notorious cowboy criminals such as Butch Cassidy and Will Carver wearing them. Even those who weren’t criminals liked the Derby hat on the frontier, because they stayed on in windy conditions and protected the cowboys from the sand. I think anyone who has ever had a hat or cap blow off in the wind can relate

to that.

to that.

While most cowboys today, and even those who just like “all things country” prefer the cowboy hat these days, and the manufacture of cowboy hats is big business these days, they certainly didn’t start out that way. It’s hard for me to picture cowboys in a Derby hat, but history would prove that the Derby hat was, in fact, what they wore.

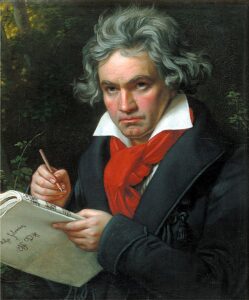

Most people have heard of Ludwig van Beethoven, whether they like his music or not. Most people also know that Beethoven was a deaf musician. I think many people think he was born deaf, but that makes no sense. If he had been born deaf, why would he have ever been interested in music? You really don’t desire to play music that you cannot hear. I don’t think that the mind of a child born deaf would simply have no concept of sound…much less music. Of course, these days, more can be done restore hearing than in Beethoven’s time, but even now, I don’t know if hearing could be restored to someone who was completely deaf from birth.

Most people have heard of Ludwig van Beethoven, whether they like his music or not. Most people also know that Beethoven was a deaf musician. I think many people think he was born deaf, but that makes no sense. If he had been born deaf, why would he have ever been interested in music? You really don’t desire to play music that you cannot hear. I don’t think that the mind of a child born deaf would simply have no concept of sound…much less music. Of course, these days, more can be done restore hearing than in Beethoven’s time, but even now, I don’t know if hearing could be restored to someone who was completely deaf from birth.

As a young man, with normal hearing, Beethoven became interested in music, and proved to be a musical genius. His hearing began to go in his 20s, and I have no doubt that it was a devastating event for him. Imagine being a man with a love of music, suddenly realizing that there will come a day when he can no longer hear the music he loves. Beethoven began to try to figure out a way to continue to have the music he loved, and he came up with a way to play the piano and “hear” the way  his music sounded…vibrations. Vibrations, you say!! Yes!! Beethoven began to experiment on what vibrations occurred when each note was placed. I find that amazing. To be able to distinguish between the vibration B-flat makes as opposed to F-sharp. Any musician can easily tell you which note is which, but could they explain the vibration each one makes. I seriously doubt it.

his music sounded…vibrations. Vibrations, you say!! Yes!! Beethoven began to experiment on what vibrations occurred when each note was placed. I find that amazing. To be able to distinguish between the vibration B-flat makes as opposed to F-sharp. Any musician can easily tell you which note is which, but could they explain the vibration each one makes. I seriously doubt it.

Beethoven not only learned to distinguish the vibrations for each note, but he could quickly put them together in an order that made music that was truly beautiful. No sour notes in his music. No, his music was perfection, but exactly how did he do it. Well, he replicated “hearing” using vibrations by attaching a small rod to the piano and biting down on it while he played. Because our eardrums vibrate from sound, the vibration on Beethoven’s jaw imitated hearing while he was hearing impaired. Totally amazing!! This experiment was the start to the official alternate hearing method called bone conduction. And now you know where some of our greatest innovations in hearing came from.

When we think of language, we think of a way to communicate, but we never really think of…safety. Why would we? After all, language is just communication, and can’t cause violence…can it? Well, it can, and never was that made more obvious than during the early 1800s, when Napoleon Bonapart’s French Army was involved in a war. At night, the soldiers would have a few minutes to read letters from home, but to do so, they had to turn on a lantern. Unfortunately, when the lanterns were turned on, the men became targets. Napoleon needed to find a way to allow his men to receive news from home, while also keeping them safe.

When we think of language, we think of a way to communicate, but we never really think of…safety. Why would we? After all, language is just communication, and can’t cause violence…can it? Well, it can, and never was that made more obvious than during the early 1800s, when Napoleon Bonapart’s French Army was involved in a war. At night, the soldiers would have a few minutes to read letters from home, but to do so, they had to turn on a lantern. Unfortunately, when the lanterns were turned on, the men became targets. Napoleon needed to find a way to allow his men to receive news from home, while also keeping them safe.

That was where a man named Charles Barbier came in. Barbier had served in Napoleon’s French army, and he was the one to develop a unique system known as “night writing” so soldiers could communicate safely during the night. As a military veteran, Barbier saw several soldiers killed because they used lamps after dark to read combat messages. As a result of the light shining from the lamps, enemy combatants knew where the French soldiers were and inevitably led to the loss of many men. The lanterns gave away their positions, and the enemy only had to shoot at the lights.

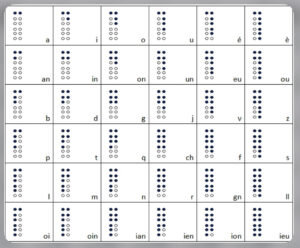

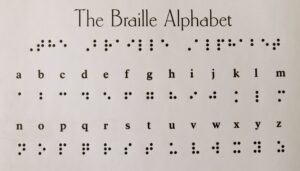

Barbier, came up with a raised dot system that communicated general words or sounds so the soldiers could effectively communicate necessities at night. It was very similar to modern day Braille, which is what it became when Louis Braille refined it. Braille was blinded at the age of three in one eye as a result of an accident with a stitching awl in his father’s harness making shop. After the accident, his eye became infected and spread to

both eyes, resulting in total blindness. The “night writing” system on a raised 12-dot cell, two dots wide and six dots tall, didn’t work well, because while each dot or combination of dots within the cell represented a letter or a phonetic sound, the problem with the military code was that the human fingertip could not feel all the dots with one touch. When Braille refined it, it was very different, but it worked better, and that has become the well-known system we have today.

both eyes, resulting in total blindness. The “night writing” system on a raised 12-dot cell, two dots wide and six dots tall, didn’t work well, because while each dot or combination of dots within the cell represented a letter or a phonetic sound, the problem with the military code was that the human fingertip could not feel all the dots with one touch. When Braille refined it, it was very different, but it worked better, and that has become the well-known system we have today.