History

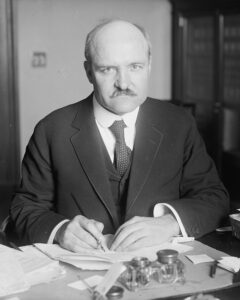

No matter what your opinion is on the use of Daylight Savings Time and Standard Time, the was originally a good reason for it, and that reason still applies today in many ways. The Standard Time Act of 1918, which was also known as the Calder Act (after the senator who sponsored the bill…William M. Calder), was the first United States federal law implementing Standard time and Daylight Saving Time in the United States. Prior to the Calder Act, the railroads had instituted time zones so that the rail schedule could have much needed consistency. Before time zones, no one had any idea when the train was due. It was a big mess. The Time Zone system defined five time zones for the United States and authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to define the limits of each time zone.

No matter what your opinion is on the use of Daylight Savings Time and Standard Time, the was originally a good reason for it, and that reason still applies today in many ways. The Standard Time Act of 1918, which was also known as the Calder Act (after the senator who sponsored the bill…William M. Calder), was the first United States federal law implementing Standard time and Daylight Saving Time in the United States. Prior to the Calder Act, the railroads had instituted time zones so that the rail schedule could have much needed consistency. Before time zones, no one had any idea when the train was due. It was a big mess. The Time Zone system defined five time zones for the United States and authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to define the limits of each time zone.

When the need for Daylight Savings Time came up, the original point of it was to save fuel by setting working hours so they coincided with the hours of natural daylight. While many people may not like that much, I think that a sensible person  can at least see the purpose of it. The act included a section that talked about the repeal of the change in one year, but in the end, it was decided that it was necessary to continue the practice. In fact, they could see no usefulness in repealing it, because the fuel savings had not changed. So, the practice has continued to this day. The Calder Act came about in answer to the European countries, who were already using the practice successfully.

can at least see the purpose of it. The act included a section that talked about the repeal of the change in one year, but in the end, it was decided that it was necessary to continue the practice. In fact, they could see no usefulness in repealing it, because the fuel savings had not changed. So, the practice has continued to this day. The Calder Act came about in answer to the European countries, who were already using the practice successfully.

Those who dislike the practice have been trying to repeal the act for as long as I can remember anyway, and with no success. I suppose that someday, they may succeed, but I’m not sure they will find that life without the time changes will be as amazing as they think. The sun will continue to make its  seasonal adjustments, and without the time changes, we will at some point, find ourselves wishing for another hour of daylight. The first time change to Daylight Saving Time took place on March 19, 1918, and it has been in practice since that time. I, personally, look forward to Daylight Saving Time every year. The longer days and more light make me feel happy, and I find that the few days or a week of adjustment is of little consequence in the grand scheme of things. Nevertheless, I’m sure I’ll hear lots of differing opinions from my readers. This year, Daylight Saving Time started on March 12, and Standard Time will begin on November 5…just so you know.

seasonal adjustments, and without the time changes, we will at some point, find ourselves wishing for another hour of daylight. The first time change to Daylight Saving Time took place on March 19, 1918, and it has been in practice since that time. I, personally, look forward to Daylight Saving Time every year. The longer days and more light make me feel happy, and I find that the few days or a week of adjustment is of little consequence in the grand scheme of things. Nevertheless, I’m sure I’ll hear lots of differing opinions from my readers. This year, Daylight Saving Time started on March 12, and Standard Time will begin on November 5…just so you know.

Years ago, when natural gas was first being used for energy, it had no odor, and so, if there was a leak, there was no warning. Natural gas was considered safe, and for the most part, it was, but when it leaked, and fumes pooled, any spark could be deadly. There is another kind of natural gas, called wet-gas that is less stable that natural gas, and probably should never have been used, but in the 1930s, the dangers were less known. Natural gas was more expensive, so sometimes consumers…mostly large consumers opted for the cheaper wet-gas to save a little money.

Years ago, when natural gas was first being used for energy, it had no odor, and so, if there was a leak, there was no warning. Natural gas was considered safe, and for the most part, it was, but when it leaked, and fumes pooled, any spark could be deadly. There is another kind of natural gas, called wet-gas that is less stable that natural gas, and probably should never have been used, but in the 1930s, the dangers were less known. Natural gas was more expensive, so sometimes consumers…mostly large consumers opted for the cheaper wet-gas to save a little money.

The Consolidated School of New London, Texas actually sat in the middle of a large oil and natural gas field. Texas is known for its oil and natural gas fields, and it wasn’t uncommon for towns to be build right in the middle of the fields. The area of New London was dominated by 10,000 oil derricks, 11 of which stood right on school grounds. The school, costing close to $1 million, was newly built in the 1930s and, from its inception, it bought natural gas from Union Gas to supply its energy needs. The school’s monthly natural gas bill averaged about $300 a month, and with such an exorbitant bill, the school officials were eventually persuaded to save money by switching over to the wet-gas lines, which were operated by Parade Oil Company. The lines ran near the school, and the cost to use them was definitely less. Wet-gas is a type of waste gas that has more impurities than typical natural gas and wasn’t as safe. Still, at the time, it wasn’t uncommon for consumers living near oil fields to use this gas.

On March 18, 1937, at approximately 3:05pm, a Thursday afternoon, school was about to end for the day, and  the 694 students and 40 teachers at the Consolidated School were waiting for the final bell, which was to ring in 10 minutes. It was not the final bell that was heard, but rather a huge explosion and powerful explosion shook the region. The blast literally blew the roof off of the building, leveled the school. There was no warning, because back then, natural gas was odorless. Nevertheless, in the presence of the leaking fumes, a single spark…or even static electricity, had the ability to create an explosion of indescribable proportions…and that is exactly what happened. When the blast came, it could be felt 40 miles away and most of the victims were killed instantly. From all over town, and even the surrounding towns, rescue workers and even everyday citizens rushed to the scene to pull out survivors. Surprisingly, hundreds of injured students were hauled from the rubble, and some students miraculously walked away unharmed. Ten students were found under a large bookcase that, when it fell, actually shielded them from the falling building. The rescue workers quickly established first-aid stations in the nearby towns of Tyler, Overton, Kilgore, and Henderson to tend to the wounded. It was noted that a blackboard at the destroyed school was found that read, “Oil and natural gas are East Texas’ greatest natural gifts. Without them, this school would not be here and none of us would be learning our lessons.” Yes, they were, but they could also be the greatest danger.

the 694 students and 40 teachers at the Consolidated School were waiting for the final bell, which was to ring in 10 minutes. It was not the final bell that was heard, but rather a huge explosion and powerful explosion shook the region. The blast literally blew the roof off of the building, leveled the school. There was no warning, because back then, natural gas was odorless. Nevertheless, in the presence of the leaking fumes, a single spark…or even static electricity, had the ability to create an explosion of indescribable proportions…and that is exactly what happened. When the blast came, it could be felt 40 miles away and most of the victims were killed instantly. From all over town, and even the surrounding towns, rescue workers and even everyday citizens rushed to the scene to pull out survivors. Surprisingly, hundreds of injured students were hauled from the rubble, and some students miraculously walked away unharmed. Ten students were found under a large bookcase that, when it fell, actually shielded them from the falling building. The rescue workers quickly established first-aid stations in the nearby towns of Tyler, Overton, Kilgore, and Henderson to tend to the wounded. It was noted that a blackboard at the destroyed school was found that read, “Oil and natural gas are East Texas’ greatest natural gifts. Without them, this school would not be here and none of us would be learning our lessons.” Yes, they were, but they could also be the greatest danger.

The investigators were never able to determine the exact cause of the spark that ignited the gas, noting that it very well may have been simple static electricity. Sadly, the dangers of wet-gas came more to light because of this incident, and as a result wet gas was required to be burned at the site rather than piped away. Also, as a safety precaution, a new state law was put into place, mandating the usage of malodorants in natural gas for  commercial and industrial use. This would provide a warning to anyone in the area of a natural gas leak, and hopefully prevent large casualties such as the ones felt in this explosion. The number of people estimated killed in the explosion is 294, but the actual number of victims remains unknown. The majority were from grades five through eleven, because the younger students were educated in a separate building, and most of them had already been dismissed from school. Many of the victims were only identified by their clothing or fingerprints, which was only available because many inhabitants of the surrounding area had been fingerprinted at the Texas Centennial Exposition the previous summer. Who could have known the importance of that exposition?

commercial and industrial use. This would provide a warning to anyone in the area of a natural gas leak, and hopefully prevent large casualties such as the ones felt in this explosion. The number of people estimated killed in the explosion is 294, but the actual number of victims remains unknown. The majority were from grades five through eleven, because the younger students were educated in a separate building, and most of them had already been dismissed from school. Many of the victims were only identified by their clothing or fingerprints, which was only available because many inhabitants of the surrounding area had been fingerprinted at the Texas Centennial Exposition the previous summer. Who could have known the importance of that exposition?

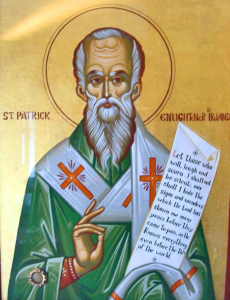

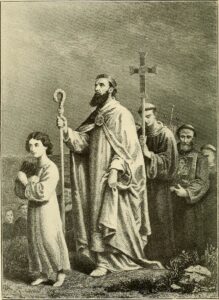

Today is Saint Patrick’s Day, but I don’t believe in Luck. I believe in blessed. Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations are all about “the luck” of the Irish. I’m not real sure where that idea got started, and I know that it’s all in fun, but luck isn’t real, and blessing is. Saint Patrick was born in Britain, but he was kidnapped by Irish pirates at 16 and enslaved for six years. They took him to Ireland where he was enslaved and held captive for six years. Patrick writes in the Confession that “the time he spent in captivity was critical to his spiritual development.” Often it is when we are our lowest time, that we finally look up and find the Lord. He explains that “the Lord had mercy on his youth and ignorance and afforded him the opportunity to be forgiven his sins and convert to Christianity.” While Saint Patrick was held in captivity, he was assigned to work as a shepherd, but while there, he also strengthened his relationship with God through prayer, eventually leading him to convert to Christianity.

Today is Saint Patrick’s Day, but I don’t believe in Luck. I believe in blessed. Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations are all about “the luck” of the Irish. I’m not real sure where that idea got started, and I know that it’s all in fun, but luck isn’t real, and blessing is. Saint Patrick was born in Britain, but he was kidnapped by Irish pirates at 16 and enslaved for six years. They took him to Ireland where he was enslaved and held captive for six years. Patrick writes in the Confession that “the time he spent in captivity was critical to his spiritual development.” Often it is when we are our lowest time, that we finally look up and find the Lord. He explains that “the Lord had mercy on his youth and ignorance and afforded him the opportunity to be forgiven his sins and convert to Christianity.” While Saint Patrick was held in captivity, he was assigned to work as a shepherd, but while there, he also strengthened his relationship with God through prayer, eventually leading him to convert to Christianity.

After six years of captivity, Patrick heard a voice telling him in a dream that he would soon go home, and then that his ship was ready. There was no “luck” to it. God spoke to him in a dream, and he obeyed. He was blessed with his freedom. He immediately took action, and escaping from his master, he  travelled to a port, two hundred miles away. Once there, Patrick found a ship and with difficulty persuaded the captain to take him. After three days of sailing, they landed, presumably in Britain. Odd that they didn’t seem to know. All the passengers and crew left the ship, walking for 28 days in a “wilderness” and almost starving to death. After Patrick prayed for sustenance, they encountered a herd of wild boar, and since this was shortly after Patrick had urged them to put their faith in God, his reputation as a man of God grew. By the time Patrick arrived back to his family, he was a young man of twenty years. Patrick continued to study Christianity.

travelled to a port, two hundred miles away. Once there, Patrick found a ship and with difficulty persuaded the captain to take him. After three days of sailing, they landed, presumably in Britain. Odd that they didn’t seem to know. All the passengers and crew left the ship, walking for 28 days in a “wilderness” and almost starving to death. After Patrick prayed for sustenance, they encountered a herd of wild boar, and since this was shortly after Patrick had urged them to put their faith in God, his reputation as a man of God grew. By the time Patrick arrived back to his family, he was a young man of twenty years. Patrick continued to study Christianity.

After making his escape, Saint Patrick, who wasn’t a saint then, made his way back to Britain, but Ireland beckoned him, and he would eventually go back there. Patrick had a vision a few years after returning home, “I saw a man coming, as it were from Ireland. His name was Victoricus, and he carried many letters, and he gave  me one of them. I read the heading: ‘The Voice of the Irish,’ As I began the letter, I imagined in that moment that I heard the voice of those very people who were near the wood of Foclut, which is beside the western sea, and they cried out, as with one voice: ‘We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us.'” A.B.E. Hood suggests that the Victoricus of Saint Patrick’s vision may be identified with Saint Victricius, bishop of Rouen in the late fourth century, who had visited Britain in an official capacity in 396. However, Ludwig Bieler disagrees. I guess we will ever really know.

me one of them. I read the heading: ‘The Voice of the Irish,’ As I began the letter, I imagined in that moment that I heard the voice of those very people who were near the wood of Foclut, which is beside the western sea, and they cried out, as with one voice: ‘We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us.'” A.B.E. Hood suggests that the Victoricus of Saint Patrick’s vision may be identified with Saint Victricius, bishop of Rouen in the late fourth century, who had visited Britain in an official capacity in 396. However, Ludwig Bieler disagrees. I guess we will ever really know.

Acting on his vision, Patrick returned to Ireland as a Christian missionary, and that is how he became a patron saint of Ireland. Saint Patrick actually never used a four-leaf clover, but rather he used a three-leaf clover as a way to help people to understand the Trinity (Triune God – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit).

Every day, in various locations, we could find ourselves in relatively close proximity to any number of known criminals. I suppose that if one were to let oneself, that could be a source of concern, but it is also good to know that often, the criminal element in our midst is trying just as hard not to be seen, as we are not to know they are there.

Every day, in various locations, we could find ourselves in relatively close proximity to any number of known criminals. I suppose that if one were to let oneself, that could be a source of concern, but it is also good to know that often, the criminal element in our midst is trying just as hard not to be seen, as we are not to know they are there.

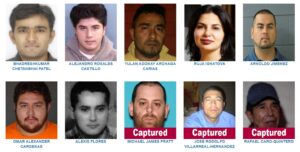

Many of those criminals are not seriously dangerous, but some are so dangerous that it was decided that the public needed to not only be aware of them, but needed to help in spotting this dangerous element, so they could be taken off our streets. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) made the decision in 1949 to institute what is now well known as the “Ten Most Wanted Fugitives” list in an effort to publicize particularly dangerous fugitives. The creation of the program arose out of a wire service news story in 1949 about the “toughest guys” the FBI wanted to capture. Once out there, like many new ideas, awareness grew, and a need was realized. The wire service story drew so much public attention that the “Ten Most Wanted” list was given the okay by J Edgar Hoover the following year.

Since its debut, the list has been responsible for the capture of hundreds of the criminals included on the list. To add to the success, more than 150 of those apprehended or located were a direct result of tips from the public. To start the list and in subsequent lists, the Criminal Investigative Division (CID) of the FBI asks all fifty-six field offices to submit candidates for inclusion on the list. Once these are received, the CID in association with the Office of Public and Congressional Affairs reviews then and proposes finalists for approval of by the FBI’s Deputy Director. The criterion for selection is simple. The criminal must have a lengthy record and current pending charges that make him or her particularly dangerous. In addition, the FBI must believe that “the publicity attendant to placement on the list will assist in the apprehension of the fugitive.”

Once on the list, there is generally only two ways to get off the list…die or to be captured. There have only been a handful of cases where a fugitive has been removed from the list because they no longer were a particularly dangerous menace to society. I suppose an older fugitive, known to have an illness or dementia would qualify. The list usually consists of men, but there have actually been ten women who have appeared on the Ten Most Wanted list. The first woman was Ruth Eisemann-Schier was the first, listed in 1968. The current list has a little room, I see.

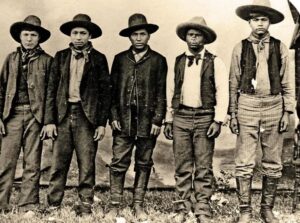

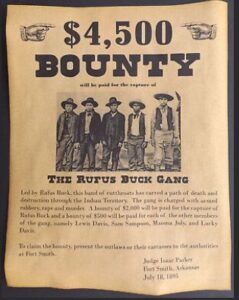

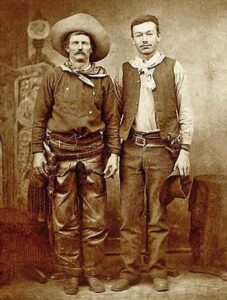

The Rufus Buck Gang was a multiracial group of African American and Native American outlaws, notorious for a series of murders, robberies, and assaults. They were a brutal bunch, and they considered anyone fair game…men, women, and children. Headed up by Rufus Buck, the gang also consisted of Lucky Davis, Maoma July, Lewis Davis, and Sam Sampson. The men had no scruples and no respect for life. Their criminal activities took place in the Indian Territory of the Arkansas-Oklahoma area from July 30, 1895, through August 4, 1896.

The Rufus Buck Gang was a multiracial group of African American and Native American outlaws, notorious for a series of murders, robberies, and assaults. They were a brutal bunch, and they considered anyone fair game…men, women, and children. Headed up by Rufus Buck, the gang also consisted of Lucky Davis, Maoma July, Lewis Davis, and Sam Sampson. The men had no scruples and no respect for life. Their criminal activities took place in the Indian Territory of the Arkansas-Oklahoma area from July 30, 1895, through August 4, 1896.

Before they started their crime spree, the gang began while staying in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, by building up a small stockpile of weapons. Then, on  July 30, 1895, they killed Deputy US Marshal John Garrett. With the lawman out of the way, they began holding up various stores and ranches in the Fort Smith area over the next two weeks. Then, the brutality began. During one robbery, a salesman named Callahan, after being robbed, was offered a chance to escape…if he could outrun the gang. Callahan was an elderly man, and they thought an easy mark, but he successfully escaped, which angered the men, so the gang killed his assistant in frustration. At least two female victims who were raped by the gang died of their injuries.

July 30, 1895, they killed Deputy US Marshal John Garrett. With the lawman out of the way, they began holding up various stores and ranches in the Fort Smith area over the next two weeks. Then, the brutality began. During one robbery, a salesman named Callahan, after being robbed, was offered a chance to escape…if he could outrun the gang. Callahan was an elderly man, and they thought an easy mark, but he successfully escaped, which angered the men, so the gang killed his assistant in frustration. At least two female victims who were raped by the gang died of their injuries.

In all, the gang, Killed Deputy US Marshal John Garrett. Then on July 31, 1895, they came across a white man and his daughter in a wagon, the gang held the man at gunpoint and took the girl. They killed a black boy and beat Ben Callahan until they mistakenly believed he was dead, then took Callahan’s boots, money, and saddle. They robbed the country stores of West and J Norrberg at Orket, Oklahoma. They murdered two white women and a 14-year-old girl. Then, on August 4th, they raped a Mrs Hassen near Sapulpa, Oklahoma. Hassen and two of three other female victims of the gang…a Miss Ayres and an Indian girl  near Sapulpa, all died; and a fourth victim, Mrs Wilson recovered from her injuries. Continuing attacks on both local settlers and Creek indiscriminately, the gang was finally captured outside Muskogee by a combined force of lawmen and Indian police of the Creek Light Horse, led by Marshal S Morton Rutherford, on August 10. While the Creek Light Horse forces wanted to hold the gang for trial, the men were brought before “Hanging” Judge Isaac Parker. The judge twice sentenced them to death, the first sentence not being carried out pending an ultimately unsuccessful appeal to the Supreme Court. They were hanged on July 1, 1896 at 1pm at Fort Smith.

near Sapulpa, all died; and a fourth victim, Mrs Wilson recovered from her injuries. Continuing attacks on both local settlers and Creek indiscriminately, the gang was finally captured outside Muskogee by a combined force of lawmen and Indian police of the Creek Light Horse, led by Marshal S Morton Rutherford, on August 10. While the Creek Light Horse forces wanted to hold the gang for trial, the men were brought before “Hanging” Judge Isaac Parker. The judge twice sentenced them to death, the first sentence not being carried out pending an ultimately unsuccessful appeal to the Supreme Court. They were hanged on July 1, 1896 at 1pm at Fort Smith.

Few kids know what they want to do with their lives by the time they are ten or twelve, but twelve-year-old British fossil collector and paleontologist Mary Anning already knew. She was the child of a poor family, and she made her first archeological discovery the year she turned twelve. Anning searched for fossils in the area’s Blue Lias cliffs, particularly during the winter months when landslides exposed new fossils that had to be collected quickly before they were lost to the sea. One day, while fossil-hunting on the cliffs of Lyme Regis, England, Anning found what was believed to be the first dinosaur skeleton…an ichthyosaur, a prehistoric reptile.

Few kids know what they want to do with their lives by the time they are ten or twelve, but twelve-year-old British fossil collector and paleontologist Mary Anning already knew. She was the child of a poor family, and she made her first archeological discovery the year she turned twelve. Anning searched for fossils in the area’s Blue Lias cliffs, particularly during the winter months when landslides exposed new fossils that had to be collected quickly before they were lost to the sea. One day, while fossil-hunting on the cliffs of Lyme Regis, England, Anning found what was believed to be the first dinosaur skeleton…an ichthyosaur, a prehistoric reptile.

Prior to Anning’s discovery, people didn’t believe that anima extinction was a real thing. Anning was up against some big obstacles in the field of science, because of her gender, so it was amazing that her findings were given any credence at all. In addition, her social class…a big thing in those days, also made it difficult for her to fully participate in the scientific community of 19th-century Britain. Nevertheless, she read as much scientific literature as she could get her hands on and went on to become a renowned fossil-hunter and dealer, often risking her life in the face of landslides and daunting cliffs. She was not going to let her gender or social class stop her from using her mind to its fullest capacity. She wanted to learn more and discover more, and she was determined to do so. Anning did get some of the recognition she deserved when the great Stephen Jay Gould, who was the most beloved popular science writer of all time, called her “probably the most important unsung (or inadequately sung) collecting force in the history of paleontology.” To say the least, her work started a fundamental shift in scientific thinking about prehistoric life in the early 19th century.

Mary Anning was born on May 21, 1799. She struggled financially for much of her life. Her family was poor. Her father, a cabinetmaker, died when she was eleven. Anning, herself, nearly died in 1833 during a landslide that killed her dog, Tray. Working in landslide conditions was dangerous, but it was often her only chance to make her discoveries. Nevertheless, this English fossil collector, dealer, and paleontologist, went on to become known around the world for important finds she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel. In addition to the ichthyosaur, she found the first two more complete plesiosaur skeletons, the first pterosaur skeleton located outside Germany, and important fish fossils. Her observations also played a key role in the discovery that “coprolites, known as bezoar stones at the time, were fossilized feces. She also discovered that belemnite fossils contained fossilized ink sacs like those of modern cephalopods.” When geologist Henry De la Beche painted Duria Antiquior, the first widely circulated pictorial representation of a scene from prehistoric life derived from fossil reconstructions, he based it largely on fossils Anning had found, and sold prints of it for her benefit. A wonderful act of kindness.

Anning was not able to fully participate in the scientific community of 19th-century Britain, who were mostly Anglican gentlemen. Nevertheless, she became well known in geological circles in Britain, Europe, and America, and was consulted on issues of anatomy, as well as about collecting fossils. Still, as a woman, she was not eligible to join the Geological Society of London and she did not always receive full credit for her scientific  contributions…and incredible injustice. As a result, she wrote in a letter, “The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.” There was only one scientific writing of hers that was published in her lifetime. It appeared in the Magazine of Natural History in 1839. It was simply an extract from a letter that Anning had written to the magazine’s editor questioning one of its claims. It seems surprising to me that they printed that at all.

contributions…and incredible injustice. As a result, she wrote in a letter, “The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.” There was only one scientific writing of hers that was published in her lifetime. It appeared in the Magazine of Natural History in 1839. It was simply an extract from a letter that Anning had written to the magazine’s editor questioning one of its claims. It seems surprising to me that they printed that at all.

After her death on March 9, 1847, her unusual life story finally began to gain the interest it deserved. An uncredited author in All the Year Round, edited by Charles Dickens, wrote of her in 1865 that “[t]he carpenter’s daughter has won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it.” It has often been claimed that her story was the inspiration for the 1908 tongue-twister “She sells seashells on the seashore” by Terry Sullivan, but that has not been confirmed. In 2010, a full 163 years after her death, the Royal Society finally included Anning in a list of the ten British women who have most influenced the history of science. Rather late in all reality.

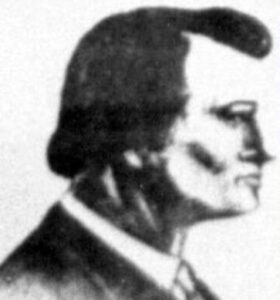

Joseph Alfred “Jack” Slade was a stagecoach and Pony Express superintendent early in his life. He was instrumental in the opening of the American West, and he was also the archetype of the Western gunslinger. Slade was born on January 22, 1831, in Carlyle, Illinois, the son of Illinois politician Charles Slade and Mary Dark (Kain) Slade. Slade’s life started out decent. He served in the US Army that occupied Santa Fe, 1847-1848, during the Mexican War. His father died in 1834, Slade’s mother married Civil War General Elias Dennis in 1838, when Slade was just seven years old.

Joseph Alfred “Jack” Slade was a stagecoach and Pony Express superintendent early in his life. He was instrumental in the opening of the American West, and he was also the archetype of the Western gunslinger. Slade was born on January 22, 1831, in Carlyle, Illinois, the son of Illinois politician Charles Slade and Mary Dark (Kain) Slade. Slade’s life started out decent. He served in the US Army that occupied Santa Fe, 1847-1848, during the Mexican War. His father died in 1834, Slade’s mother married Civil War General Elias Dennis in 1838, when Slade was just seven years old.

In about 1857, Slade married a woman named Maria Virginia. Her maiden name is unknown. In the 1850s, he was a freighting teamster and wagon master along the Overland Trail, and then became a stagecoach driver in Texas, around 1857-1858. After years on the job, Slade became a stagecoach division superintendent along the Central Overland route for Hockaday and Company from 1858–1859, and when it was purchased, he worked for its successors Jones, Russell and Company in 1859 and Central Overland, California and Pike’s Peak Express Company from 1859 to 1862. With the latter concern, he also helped launch and operate the Pony Express in 1860-61. These were critical lines of communication between the East and California. As superintendent, he enforced order and assured reliable cross-continental mail service, maintaining contact between Washington DC, and California on the eve of Civil War.

Slade was know as a strict, and even ferocious boss. While division superintendent, he shot and killed Andrew Ferrin, one of his subordinates, who was hindering the progress of a freight train, in May 1859. This type of situation was rare for the time, but it served to build his reputation as a gunslinger. In March 1860, Slade was ambushed and left for dead by Jules Beni, who was a corrupt stationkeeper at Julesburg, Colorado, and whom Slade had removed. Remarkably, Slade survived, and in August 1861, Beni was killed by Slade’s men after  ignoring Slade’s warning to stay out of his territory.

ignoring Slade’s warning to stay out of his territory.

Slade’s temper and the reputation that came with it, combined with a drinking problem, caused his downfall. After he was fired by the Central Overland for drunkenness in November 1862, Slade crossed paths with the Virginia City Vigilance Committee, which was composed of honest, determined citizens, including bankers, storekeepers, miners, stockbrokers, and other citizens of all backgrounds, who had decided to take the law into their own hands and combat lawlessness in Virginia City. Slade found himself in Virginia City, Montana on a drunken spree. After being arrested, he was lynched by local vigilantes on March 10, 1864, for disturbing the peace. Of all the killings he was guilty of, Slade was lynched for disturbing the peace. Unbelievable, but the truth, nevertheless. He was buried in Salt Lake City, Utah, on July 20, 1864.

Soldiers everywhere have varied backgrounds, but maybe more so during World War I and World War II, as well as wars in which there was a draft. Robert Kerr “Jock” McLaren was a veterinarian by trade, but during his service with the Second Australian Imperial Force, he also became a feared guerrilla fighter who ran missions against the Japanese. I suppose that, while a veterinarian doesn’t work on humans, possessing certain skills would be important in certain situations. McLaren spent countless hours, days, and weeks in the jungles, and after one such assignment, his medical skills suddenly became urgently needed…on himself. McLaren found himself faced with surgery on himself, or certain death. So, in order to save his own life, McLaren set about to remove his own appendix…in the jungle, with a pen knife, two spoons, and coconut fibers.

Soldiers everywhere have varied backgrounds, but maybe more so during World War I and World War II, as well as wars in which there was a draft. Robert Kerr “Jock” McLaren was a veterinarian by trade, but during his service with the Second Australian Imperial Force, he also became a feared guerrilla fighter who ran missions against the Japanese. I suppose that, while a veterinarian doesn’t work on humans, possessing certain skills would be important in certain situations. McLaren spent countless hours, days, and weeks in the jungles, and after one such assignment, his medical skills suddenly became urgently needed…on himself. McLaren found himself faced with surgery on himself, or certain death. So, in order to save his own life, McLaren set about to remove his own appendix…in the jungle, with a pen knife, two spoons, and coconut fibers.

McLaren was just a teenager during World War I, when he served with the 51st (Highland) Division of the British Army. Because he was so young then, it’s unlikely that he saw combat on the Western Front. Nevertheless, his name is found on the rolls from his division’s time in France in 1918. That made people wonder if he participated in fighting during the Spring Offensive. Following the war, McLaren returned to  Scotland and completed training to become a veterinarian. He then moved to Queensland, Australia, where he worked as a veterinary officer in Bundaberg.

Scotland and completed training to become a veterinarian. He then moved to Queensland, Australia, where he worked as a veterinary officer in Bundaberg.

When World War II began, McLaren volunteered for the Second Australian Imperial Force. McLaren, 39 years old at the time, was assigned to the 2/10th Australian Field Workshops, 8th Australian Division and stationed in Singapore. McLaren spent time in a POW camp and escaped along with two other soldiers. After being tortured and faced with a firing squad, the trio were ultimately returned to their cells. McLaren, along with 1,000 British and Australian soldiers, was later transferred to Borneo and held at the Sandakan camp. He made plans to escape again, this time with a Chinese POW named Johnny Funk. The escape took the men to the large Philippine Island of Mindanao, where they joined the resistance led by American Reserve Officer, Lt. Col. Wendell Fertig. He was later given the chance to return to Australia, but chose to remain a guerrilla.

It was during his time as a guerrilla that McLaren’s appendicitis attack occurred. During one patrol as a  guerrilla, McLaren developed a severe case of appendicitis. He knew enough to know that he was going to have to treat himself, or he would die. So, he performed surgery with just a penknife and two spoons. He stitched the incision with coconut fibers. When asked about the act years later, he said, “It was hell, but I came through alright.” A modest remark for such a remarkable act…in the middle of a Philippine jungle in 1944, without any anesthetic and with only the use of a mirror to see. The operation took 4½ hours. Still, as he said he came through it alright, and he would not be that last person to do surgery on themselves. Nevertheless…remarkable.

guerrilla, McLaren developed a severe case of appendicitis. He knew enough to know that he was going to have to treat himself, or he would die. So, he performed surgery with just a penknife and two spoons. He stitched the incision with coconut fibers. When asked about the act years later, he said, “It was hell, but I came through alright.” A modest remark for such a remarkable act…in the middle of a Philippine jungle in 1944, without any anesthetic and with only the use of a mirror to see. The operation took 4½ hours. Still, as he said he came through it alright, and he would not be that last person to do surgery on themselves. Nevertheless…remarkable.

Who hasn’t heard of Bayer Aspirin, or at the very least, aspirin? It has been a staple in households for as many as 124 years…until the Tylenol push, which in my opinion is the least effective pain medication of all time!!! Aspirin was developed from acetylsalicylic acid, which can be found in the bark of willow trees. Of course, it didn’t originate there. In its most primitive form, the active ingredient, Salicin was used for centuries in folk medicine, beginning in ancient Greece when Hippocrates used it to relieve pain and fever. I guess “modern medicine” hasn’t progressed so far after all. The Bayer version of aspirin was developed in Germany and patented on March 6, 1899. Even then, its unpleasant taste and tendency to damage the stomach, caused its sparing use. In the most modern adaptation of aspirin, the Bayer version, Bayer employee Felix Hoffmann found a way to create a stable form of the drug that was easier and more pleasant to take. Some evidence shows that Hoffmann’s work was really done by a Jewish chemist, Arthur Eichengrun, whose contributions were covered up during the Nazi era. After obtaining the patent rights, Bayer began distributing aspirin in powder form to physicians to give to their patients one gram at a time. The brand name came from “A” for acetyl, “spir” from the spirea plant, which was a source of salicin, and the suffix “in,” commonly used for medications. It quickly became the number-one drug worldwide.

Who hasn’t heard of Bayer Aspirin, or at the very least, aspirin? It has been a staple in households for as many as 124 years…until the Tylenol push, which in my opinion is the least effective pain medication of all time!!! Aspirin was developed from acetylsalicylic acid, which can be found in the bark of willow trees. Of course, it didn’t originate there. In its most primitive form, the active ingredient, Salicin was used for centuries in folk medicine, beginning in ancient Greece when Hippocrates used it to relieve pain and fever. I guess “modern medicine” hasn’t progressed so far after all. The Bayer version of aspirin was developed in Germany and patented on March 6, 1899. Even then, its unpleasant taste and tendency to damage the stomach, caused its sparing use. In the most modern adaptation of aspirin, the Bayer version, Bayer employee Felix Hoffmann found a way to create a stable form of the drug that was easier and more pleasant to take. Some evidence shows that Hoffmann’s work was really done by a Jewish chemist, Arthur Eichengrun, whose contributions were covered up during the Nazi era. After obtaining the patent rights, Bayer began distributing aspirin in powder form to physicians to give to their patients one gram at a time. The brand name came from “A” for acetyl, “spir” from the spirea plant, which was a source of salicin, and the suffix “in,” commonly used for medications. It quickly became the number-one drug worldwide.

In the beginning, like most drugs, Aspirin was a prescription-only drug, but in 1915, Aspirin was made available in tablet form and without a prescription. In 1917, when Bayer’s patent expired during the First World War, the Bayer company lost the trademark rights to aspirin in various countries. After the United States entered the war against Germany in April 1917, the Alien Property Custodian, a government agency that administers foreign property, seized Bayer’s US assets. Two years later, the Bayer company name and trademarks for the United States and Canada were auctioned off and purchased by Sterling Products Company, later Sterling Winthrop, for $5.3 million.

As companies do, with mergers and splits, Bayer became part of IG Farben, the conglomerate of German chemical industries that formed the financial heart of the Nazi regime. Then after the Nazi defeat in World War II, the Allies split apart IG Farben, and Bayer again emerged as an individual company. With its purchase of Miles Laboratories in 1978, came a product line including Alka-Seltzer and Flintstones and One-A-Day Vitamins. Then in 1994, coming full circle, Bayer bought Sterling Winthrop’s over-the-counter business, which allowed it to gain back the rights to the Bayer name and logo, and after almost 100 years, and the company once again was allowed to profit from American sales of its most famous product.

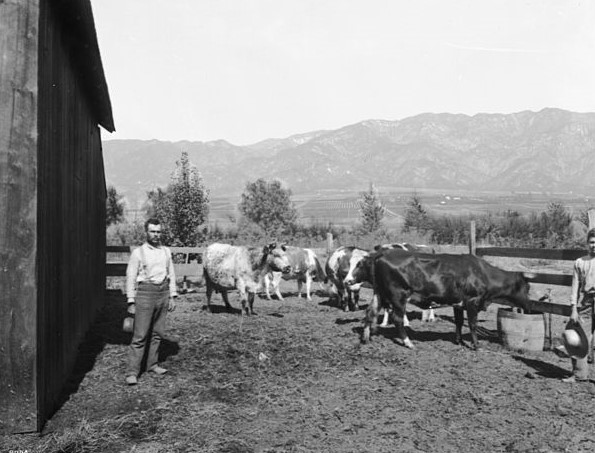

When we think of a cowboy, we usually picture the American Cowboy, rough and rugged wearing a cowboy hat, a gun on his hip, and riding he favorite horse around the Old West. One thing we wouldn’t think of is that we really wouldn’t think of an American Cowboy being born in Canada. Nevertheless, one of the most “unusual” American Cowboys was actually born in Canada. His name was Charles Nebo, or as he was known by nickname, Charley, and he was born in March of 1842. Charles Nebo wasn’t your typical cowboy and might have even been more Forrest Gump than soldier, although he wasn’t autistic, like Forrest Gump was…or at least, not that anyone knew of.

When we think of a cowboy, we usually picture the American Cowboy, rough and rugged wearing a cowboy hat, a gun on his hip, and riding he favorite horse around the Old West. One thing we wouldn’t think of is that we really wouldn’t think of an American Cowboy being born in Canada. Nevertheless, one of the most “unusual” American Cowboys was actually born in Canada. His name was Charles Nebo, or as he was known by nickname, Charley, and he was born in March of 1842. Charles Nebo wasn’t your typical cowboy and might have even been more Forrest Gump than soldier, although he wasn’t autistic, like Forrest Gump was…or at least, not that anyone knew of.

Charlie never tried to inflate his achievements and was happy to live like a true frontier man, nevertheless, people often made him sound like he was…maybe, a little bit more of a cowboy than he actually was. I suppose it made no sense to say that he was just a “good old boy” from out west. People don’t expect that, and maybe, they just wouldn’t read about it, either, but the reality is that there were more average people in the American West than there were the wild people who made the West famous.

Charley Nebo lived in Canada until 1861. Then, he moved to Saginaw, Michigan. He was a Union soldier during the Civil War and went on to become a cowboy in New Mexico. At one point he actually befriended Billy the Kid. Nebo wrote about him in a letter, saying, “He wasn’t the ruthless bad fellow that Western history has made him out to be.” Nebo apparently gave people the benefit of the doubt, and himself, as a respected cowboy, once shot a man after witnessing him kill a Mexican boy’s dog. In all, Nebo was a common man, humble and capable. He wasn’t what people might call spectacular, but he was a good man, and it took a lot of those good men to build the American West.