History

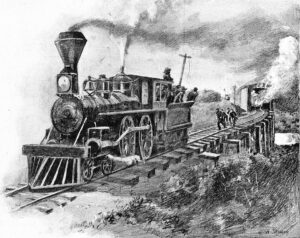

During the Civil War, things like supply lines and lines of communication were crucial to both sides. The railroads became an important asset, as well as a liability, to both sides, depending on what they were carrying and where it was headed. On April 12, 1862, volunteers from the Union Army, led by civilian scout James J Andrews, commandeered a train called The General, and took it northward from Georgia toward Chattanooga, Tennessee. En route, they did as much damage as possible to the vital Western and Atlantic Railroad (W and A) line from Atlanta to Chattanooga. They were pursued for 87 miles by Confederate forces, trying at first to keep up on foot, and later resorting to a succession of locomotives, including The Texas.

During the Civil War, things like supply lines and lines of communication were crucial to both sides. The railroads became an important asset, as well as a liability, to both sides, depending on what they were carrying and where it was headed. On April 12, 1862, volunteers from the Union Army, led by civilian scout James J Andrews, commandeered a train called The General, and took it northward from Georgia toward Chattanooga, Tennessee. En route, they did as much damage as possible to the vital Western and Atlantic Railroad (W and A) line from Atlanta to Chattanooga. They were pursued for 87 miles by Confederate forces, trying at first to keep up on foot, and later resorting to a succession of locomotives, including The Texas.

Known as The Great Locomotive Chase, the military raid was also called the Andrews’ Raid or Mitchel Raid (after Major General Ormsby Mitchel, who had earlier assisted in the capture of Nashville and accepted the surrender of the city). In the end, as often happens in escapades like this, the raid made sensational headlines in newspapers, but it really had little impact on the war. It didn’t stop supply lines for the South or start new ones for the North.

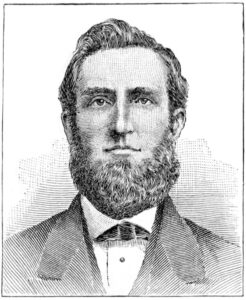

In February, the Union soldiers captured Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, and Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston knew he had to withdraw his forces from central Tennessee to reorganize. Johnston evacuated Nashville on February 23rd, and Nashville became the first Confederate state capital to fall to the Union. For Major General Don Carlos Buell, the taking of Nashville was enough, and on March 11th, Buell’s army was merged into the new Department of the Mississippi under General Henry Halleck. It was then that James J Andrews, a Kentucky-born civilian serving as a secret agent and scout in Tennessee approached Buell with a plan to take eight men to steal a train in Georgia and drive it north. Buell authorized the expedition in August 1863. Andrews, a train engineer in Atlanta, was willing to defect to the Union with his train, and without Andrews, taking over the train would have proved difficult. Getting onboard would have been easy enough, but running the train without experienced personnel is next to impossible. Since Andrews was willing to defect, he might also be able to supply a volunteer train crew to assist in running the train, tearing up track, and burning  bridges, so they would have an even greater chance of succeeding. The main target of the operation was the railway bridge at Bridgeport, Alabama, but Andrews had several other bridges in Georgia and Tennessee in mind too. Some of the men from Major General Mitchel’s division, encamped at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, were tapped to be the volunteers for this first raid.

bridges, so they would have an even greater chance of succeeding. The main target of the operation was the railway bridge at Bridgeport, Alabama, but Andrews had several other bridges in Georgia and Tennessee in mind too. Some of the men from Major General Mitchel’s division, encamped at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, were tapped to be the volunteers for this first raid.

The group of raiders moved south forty miles on foot to the Confederate railhead at Tullahoma. Then the caught a train to Marietta, Georgia. It was then that the operation hit its first snag, when Andrews discovered the engineer had been pressed into service elsewhere. Upon inquiring if any of the raiders knew how to operate a locomotive, they found that none did, and the raid was called off. Two raiders were also confronted by Confederate soldiers while trying to cut the telegraph lines, but successfully pretended to be overworked wiremen. Then the raiders returned north to Union lines, arriving about a week after they had departed. Andrews spent several days rearranging the operation and conducting reconnaissance on the Western and Atlantic Railroad before he headed north to federal lines too. The original raiders all refused to volunteer for the second raid, fearing the enemy. One said that “he felt all the time he was in the enemy’s country as though he had a rope around his neck.”

While the first raid was a bust, the second raid went off pretty well. The General was taken while the crew was a breakfast at the Lacey Hotel in Atlanta, and despite all the efforts to catch them, it arrived at milepost 116.3, north of Ringgold, Georgia, just 18 miles from Chattanooga and out of fuel. Andrews’s men abandoned The General and scattered. Andrews and all of his men were caught within two weeks. They even caught two volunteers who had the hijacking. Mitchel’s attack on Chattanooga was a failure.

All of the raiders were charged with “acts of unlawful belligerency.” The civilians among them were charged as unlawful combatants and spies. They were tried in military courts or courts-martial. Andrews was tried in

Chattanooga, found guilty, and hanged on June 7 in Atlanta. Seven others were transported to Knoxville and convicted as spies. They were returned to Atlanta and were hanged too. Their bodies were buried unceremoniously in an unmarked grave. Those bodies were later reburied in Chattanooga National Cemetery.

Chattanooga, found guilty, and hanged on June 7 in Atlanta. Seven others were transported to Knoxville and convicted as spies. They were returned to Atlanta and were hanged too. Their bodies were buried unceremoniously in an unmarked grave. Those bodies were later reburied in Chattanooga National Cemetery.

While escape seemed impossible, there were a number of successful escapes from the horrific Nazi death camp known as Auschwitz. Unfortunately, there were also many failed attempts. These escapes and attempted escapes happened, because where people are held in captivity, they will rebel and try to find a way out, and when death is inevitable, escape become less risky. Hitler wanted all the Jews dead, and while he might have tried to hide his true intentions from the world, he certainly didn’t hide it from the Jews themselves.

While escape seemed impossible, there were a number of successful escapes from the horrific Nazi death camp known as Auschwitz. Unfortunately, there were also many failed attempts. These escapes and attempted escapes happened, because where people are held in captivity, they will rebel and try to find a way out, and when death is inevitable, escape become less risky. Hitler wanted all the Jews dead, and while he might have tried to hide his true intentions from the world, he certainly didn’t hide it from the Jews themselves.

Most prisoner escapes took place from worksites outside the camp. The attitude of local civilians was of immense importance in the success of these efforts. Some of the escapees tried to get the word out that the camps were not just work camps, but were also death camps, and that the people should fight with everything they had to avoid going. Of course, all too often, any reports were suppressed as much as possible by the Germans, and for the most part, the reports did little to no good.

On escape that particularly touched me was the escape of two Slovakian Jews, Rudolf Vrba (born Walter Rosenberg) and Alfred Wetzler, escaped in April 1944. They knew the consequences of the were caught, and the men in their barracks knew the consequences of helping them, or even being in the same barracks with them. Nevertheless, all of them felt that the risk was worth it to try to get the truth to the outside world.

Trust was vital, in an escape. Vrba and Wetzler came from the same town, so they knew each other well, and could trust each other. The men had been working on this escape idea for a while, coming up with plans and then rejecting them, because they couldn’t work. Finally, Wetzler came to Vrba with a plan that just might work. They would hide in a pile of wooden planks and after the three-day search for the escapees was finished,  they would escape and head South. The plan was good, but there were still a number of obstacles to maneuver. The first group to attempt the escape were later caught in a village south of the camp, but the wooden plank plan had worked, and the captured prisoners did not reveal their strategy.

they would escape and head South. The plan was good, but there were still a number of obstacles to maneuver. The first group to attempt the escape were later caught in a village south of the camp, but the wooden plank plan had worked, and the captured prisoners did not reveal their strategy.

So, Vrba and Wetzler waited two weeks, and put their plan in motion. The had a friend help them by pulling the planks over then, and covering the area with something to hid e the scent of the men from the dogs. The men expected the alarm to sound at the 5:30pm roll call, but no alarm sounded. The men began to think that someone had told of their location, and that the guards would be coming any minute, but the alarm went of shortly after 6:00pm and the sound of boots and dogs was everywhere. It was all they could do not to scream in terror. Nevertheless, they held their peace and stayed put.

The men laid motionless for three days with no food or water. They were stiff and cold, but finally, they heard the guards call off the search, so that night they decided to come out of the wood pile and make their escape. However, the planks wouldn’t budge. They pushed and pushed…almost to the point of panic. They determined that they would not die there, they gave it one last effort, and the planks gave way. They came out into the night, made their way to the nearest fence and crawled under the barbed wire. I’m quite sure they never wanted to see a fence again.

The ran for the woods, traveling at night, and hiding by day. They were seen by a few people, but thankfully everyone who saw them was sympathetic to their cause and helped them on their way. Finally, they crossed the

border, and they were free at last. They went to Zylina, where they met secretly with officials from the Slovakia Jewish Council and gave them a secret report on Auschwitz. An in-depth report was drawn up in Slovak and German. The plan was to get the report to the world before another train load of Jews could come to Auschwitz, and the men had done their part. They had done all they could. Unfortunately, the report did not get to those who needed to hear it, and the killing would go on until January 27, 1945, when Auschwitz was finally liberated.

border, and they were free at last. They went to Zylina, where they met secretly with officials from the Slovakia Jewish Council and gave them a secret report on Auschwitz. An in-depth report was drawn up in Slovak and German. The plan was to get the report to the world before another train load of Jews could come to Auschwitz, and the men had done their part. They had done all they could. Unfortunately, the report did not get to those who needed to hear it, and the killing would go on until January 27, 1945, when Auschwitz was finally liberated.

During World WarII, and probably any war, port cities are vital for the transportation of weapons, machinery, and personnel. The port city of Tobruk on Libya’s eastern Mediterranean coast is near the border with Egypt. In World War II, that may not have seemed like a particularly important port, but the Germans must have seen it as such, because in November of 1941, the Nazis laid siege to the capital of the Butnan District (previously the Tobruk District), and home to approximately 120,000 people today (although the population in 1941 was likely less).

During World WarII, and probably any war, port cities are vital for the transportation of weapons, machinery, and personnel. The port city of Tobruk on Libya’s eastern Mediterranean coast is near the border with Egypt. In World War II, that may not have seemed like a particularly important port, but the Germans must have seen it as such, because in November of 1941, the Nazis laid siege to the capital of the Butnan District (previously the Tobruk District), and home to approximately 120,000 people today (although the population in 1941 was likely less).

Tobruk began its existence as an ancient Greek colony, but later became a Roman fortress guarding the frontier of Cyrenaica. I suppose that qualifies as an important port. Tobruk became a waystation along the coastal caravan route, over the centuries. It became an Italian military post by 1911. Then, during World War II, Allied forces, mainly the Australian 6th Division, saw it a the perfect spot for a military base, and they took Tobruk on January 22, 1941. They reached Tobruk on April 9, 1941. At that time, there was prolonged fighting against German and Italian forces. Tobruk has a strong, naturally protected deep harbor. It is probably the best natural port in northern Africa. It wasn’t as popular, because it wasn’t near any landsites.

In 1941, Axis forces took over Tobruk, in a siege that would last for 241 days. The Axis forces advanced through Cyrenaica from El Agheila in Operation Sonnenblume against Allied forces in Libya, during the Western Desert Campaign of 1940–1943 in World War II. The Allies had defeated the Italian 10th Army during Operation Compass that took place between December 9, 1940 and February 9, 1941, and trapped the remnants of the troops at Beda Fomm. Much of the Western Desert Force (WDF) was sent to the Greek and Syrian campaign in early 1941. By the time German troops and Italian reinforcements reached Libya, only a skeleton Allied force remained, and they were short of equipment and supplies. It was then that the Australian 9th Division became known as “The Rats of Tobruk” when they pulled back to Tobruk to avoid encirclement after actions at Er

Regima and Mechili. Although the siege was lifted by Operation Crusader in November 1941, a renewed offensive by Axis forces under Erwin Rommel the following year resulted in Tobruk being re-captured in June 1942 and held by the Axis forces until November 1942, when it was finally recaptured by the Allies. Rebuilt after World War II, Tobruk was later expanded during the 1960s to include a port terminal linked by an oil pipeline to the Sarir oil field.

Regima and Mechili. Although the siege was lifted by Operation Crusader in November 1941, a renewed offensive by Axis forces under Erwin Rommel the following year resulted in Tobruk being re-captured in June 1942 and held by the Axis forces until November 1942, when it was finally recaptured by the Allies. Rebuilt after World War II, Tobruk was later expanded during the 1960s to include a port terminal linked by an oil pipeline to the Sarir oil field.

For many people, the events of Good Friday, while not forgotten exactly, are “misplaced” with the upcoming commercial holiday of modern Easter. Of course, Easter or Resurrection Day, as it should be called, could not be possible, were it not for the events of Good Friday. Our world was headed for disaster. Our sins had separated us from God, and we had no way to ever get back, because the Bible tells us that “the wages of sin is death.” We couldn’t “un-sin” and so the only destination left for our lives was Hell. It was where we would all go, if something was not done to save us.

For many people, the events of Good Friday, while not forgotten exactly, are “misplaced” with the upcoming commercial holiday of modern Easter. Of course, Easter or Resurrection Day, as it should be called, could not be possible, were it not for the events of Good Friday. Our world was headed for disaster. Our sins had separated us from God, and we had no way to ever get back, because the Bible tells us that “the wages of sin is death.” We couldn’t “un-sin” and so the only destination left for our lives was Hell. It was where we would all go, if something was not done to save us.

Jesus was the only way out. He lived a sinless life, and yet accepted the beating, torture, and death on the cross, because He could see the reward in the end…the restoration of all mankind to a relationship with God again. Why did Jesus accept that horrific punishment? He did it for me…and you, and all mankind, and He purchased that salvation for anyone who wants it. I have often wondered why they called it Good Friday, but even though the death of Jesus was horrific, it was the best day ever…for mankind, anyway.

Resurrection Day is the day when the horrific job given to Jesus was completed. When He rose from the dead  on that third day, He rose in victory, having completed the task of redeeming us from the curse of the law. God knew that we couldn’t live perfect, and with Adam’s sin, and every sin that followed, we became more and more filthy and disgusting, but God so loved the world, that He gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believes on Him shall be saved. When we accept Jesus as our Lord and Savior, we are instantly put back in right standing with God. We can live out eternity in Heaven and not in Hell. It is the greatest gift of all time, and it is ours for the taking. Salvation is waiting for everyone!! We only need to believe. Happy Resurrection Day everyone!! Praise God, Jesus is risen!!

on that third day, He rose in victory, having completed the task of redeeming us from the curse of the law. God knew that we couldn’t live perfect, and with Adam’s sin, and every sin that followed, we became more and more filthy and disgusting, but God so loved the world, that He gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believes on Him shall be saved. When we accept Jesus as our Lord and Savior, we are instantly put back in right standing with God. We can live out eternity in Heaven and not in Hell. It is the greatest gift of all time, and it is ours for the taking. Salvation is waiting for everyone!! We only need to believe. Happy Resurrection Day everyone!! Praise God, Jesus is risen!!

Personally, I see no reason to jump out of a perfectly good airplane, but I know that there are countless numbers of people who absolutely love the thrill of doing just that. In fact, before planes were invented there were parachutes. In 1783, gutsy inventor Louis-Sebastian Lourmand made the first-ever recorded successful parachute jump with a rigid-frame cloth parachute 14 feet in diameter. He, of course, jumped from a balloon, because there were no planes then. I can’t imagine how that jump went. The parachute was not soft and flexible, but rigid!! My mind can see so many things going wrong with that jump. In the early years of parachute jumping, the jumpers were men, because women were considered far too “fragile” and “delicate” for such activities, so I doubt if it would have even been allowed, had a woman asked.

Personally, I see no reason to jump out of a perfectly good airplane, but I know that there are countless numbers of people who absolutely love the thrill of doing just that. In fact, before planes were invented there were parachutes. In 1783, gutsy inventor Louis-Sebastian Lourmand made the first-ever recorded successful parachute jump with a rigid-frame cloth parachute 14 feet in diameter. He, of course, jumped from a balloon, because there were no planes then. I can’t imagine how that jump went. The parachute was not soft and flexible, but rigid!! My mind can see so many things going wrong with that jump. In the early years of parachute jumping, the jumpers were men, because women were considered far too “fragile” and “delicate” for such activities, so I doubt if it would have even been allowed, had a woman asked.

That all changed when a little woman named Georgia “Tiny” Broadwick came on the scene. Born to parents George and Emma Ross on April 8, 1893, Georgia Ann Thompson weighed about 3 pounds. She was the last of seven daughters, and because of her size, she was given the nickname “Tiny” since she weighed only 85 pounds and was 4 feet 8 inches tall, when she was fully grown. In those days, women often married very young, and at age 12, Tiny Broadwick had married and, at 13, had a daughter, Verla Jacobs (later, Poythress). By 15, Broadwick was abandoned by her husband and working in a cotton mill. It was then that she saw Charles Broadwick’s World Famous Aeronauts parachute from a hot air balloon. She was hooked and decided to join the travelling troupe. She left her daughter in the care of her parents. She later actually became Broadwick’s adopted daughter, to ease travel arrangements. Rumors also flew that she was his wife, but although her own family was later unclear on the relationship, that was not proven.

Although she would eventually make her jumps from airplanes, in her early career Broadwick jumped from balloons. Nevertheless, when the time came, Georgia “Tiny” Broadwick was not afraid, and she became the first woman to jump from an airplane too. She loved parachuting, and between 1913 and 1922 she completed over 1,100 jumps. Making that many jumps taught her that parachutes needed some improvements. So, she invented the ripcord, which is standard on every parachute to this day. Broadwick is also the only female member of the Early Birds of Aviation.

In 1914, she demonstrated parachutes to the US Army. At that time, the Army had a small fleet, but they were just as likely to crash as fly. I suppose that in that situation, knowing how to get out of the plane was crucial. Nevertheless, the Army was reluctant to adopt the parachute at first. They watched Tiny fearlessly dropped

from the sky. Then, on one of her demonstration jumps, the static line became entangled in the tail assembly of the aircraft. As a solution, Tiny cut off the static line and deployed her chute manually on her next jump, thus becoming the first person to jump free-fall. This demonstrated that pilots could escape aircraft by using what was later called a ripcord, and for that she is now famous. Broadwick died in 1978 and was buried in Sunset Gardens in Henderson, North Carolina.

from the sky. Then, on one of her demonstration jumps, the static line became entangled in the tail assembly of the aircraft. As a solution, Tiny cut off the static line and deployed her chute manually on her next jump, thus becoming the first person to jump free-fall. This demonstrated that pilots could escape aircraft by using what was later called a ripcord, and for that she is now famous. Broadwick died in 1978 and was buried in Sunset Gardens in Henderson, North Carolina.

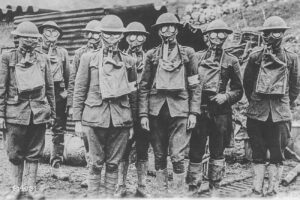

The initials “G.I.” bring a picture of a US soldier for most people They aren’t viewed as glamorous, and usually look like they have just crawled out of the trenches somewhere, but never is there a shred of doubt as to their toughness. The name, American G.I. is synonymous with “American infantryman.” Really, everything American Military was tagged G.I. When soldiers returned from World War II and now other wars or even non-wartime military service are eligible for the benefits of the “G.I.” Bill, including education. In fact, it was often the G.I. Bill that drew young recruits into the service in the first place. Let’s face it, college is expensive, and three years of service seems a small price to pay.

The initials “G.I.” bring a picture of a US soldier for most people They aren’t viewed as glamorous, and usually look like they have just crawled out of the trenches somewhere, but never is there a shred of doubt as to their toughness. The name, American G.I. is synonymous with “American infantryman.” Really, everything American Military was tagged G.I. When soldiers returned from World War II and now other wars or even non-wartime military service are eligible for the benefits of the “G.I.” Bill, including education. In fact, it was often the G.I. Bill that drew young recruits into the service in the first place. Let’s face it, college is expensive, and three years of service seems a small price to pay.

The American soldier was, and for patriots of our day is one of the most loved and respected groups of people  in the United States. They even inspired one of most popular toys in the 1960s and 1980s. the G.I. Joe doll, and later, G.I. Jane, inspired by Demi Moore in her movie with the same name. The dolls and the movie brought the G.I. Joe and Jane dolls to a whole new generation of kids.

in the United States. They even inspired one of most popular toys in the 1960s and 1980s. the G.I. Joe doll, and later, G.I. Jane, inspired by Demi Moore in her movie with the same name. The dolls and the movie brought the G.I. Joe and Jane dolls to a whole new generation of kids.

We all know about the G.I. dolls and soldiers, but do we know what G.I. means? Most of us truly don’t. Many people probably assumed it was something along the lines of “Government Infantry,” “General Infantry,” or perhaps a “Government Issue” label stamped on military rations and equipment. Those are good guesses, but they are also wrong. In fact, “G.I.” stands for “Galvanized Iron.” While that sounds like a tough thing, and  maybe that is to say that the soldiers were tough, the reality is that the name comes from something entirely different…and totally not exciting, tough, or even cool. In the early 20th century, believe it or not…military trash cans and buckets were stamped with the initials G.I. It wasn’t because they belonged to the military. but simply because galvanized iron was the material from which the cans and buckets were made. So, during World War I, the initials became a proxy for all things to do with infantry, and the usage stuck. So, I guess we can banish the initials, accept it as all things military, or maybe embrace the term as being the toughest of the tough and the strongest of the strong. I think I like the last one the best.

maybe that is to say that the soldiers were tough, the reality is that the name comes from something entirely different…and totally not exciting, tough, or even cool. In the early 20th century, believe it or not…military trash cans and buckets were stamped with the initials G.I. It wasn’t because they belonged to the military. but simply because galvanized iron was the material from which the cans and buckets were made. So, during World War I, the initials became a proxy for all things to do with infantry, and the usage stuck. So, I guess we can banish the initials, accept it as all things military, or maybe embrace the term as being the toughest of the tough and the strongest of the strong. I think I like the last one the best.

The whole thing actually started with fraud. It was probably the first disaster in United States history to be caused by fraud. The Forest Hills disaster, which was also called the Forest Ridge disaster and the Bussey Bridge train disaster, was a railroad bridge accident that occurred on March 14, 1887, in the Roslindale section of Boston, Massachusetts.

The whole thing actually started with fraud. It was probably the first disaster in United States history to be caused by fraud. The Forest Hills disaster, which was also called the Forest Ridge disaster and the Bussey Bridge train disaster, was a railroad bridge accident that occurred on March 14, 1887, in the Roslindale section of Boston, Massachusetts.

It seems strange that an act of fraud could cause a disaster, but on that day, a morning commuter train was coming into Boston and was passing over the Bussey Bridge, a Howe truss, at South Street in the Roslindale neighborhood, located a half mile from the Forest Hills station. Suddenly, without warning, the Bussey Bridge collapsed. Several cars crashed to the street below. In the aftermath of the disaster, it was found that 38 commuters were killed, and 40 others were seriously injured.

There were nine cars on this train, and it was traveling over the Dedham Branch of the Boston and Providence Railroad. It was a bright and sunny Monday morning, and about 300 passengers, including several school children were on their way into Boston. The disaster struck when they were about six miles from Boston. As  they crossed the Bussey Bridge, the locomotive and first two cars safely traversed the bridge, when suddenly, without any warning, the bridge just fell, taking the final six cars with it. It happened so fast that as the body of one of the cars fell, its roof tore off completely and landed on the embankment beyond the bridge. It was as if the roof kept going after the car dropped off of the bottom.

they crossed the Bussey Bridge, the locomotive and first two cars safely traversed the bridge, when suddenly, without any warning, the bridge just fell, taking the final six cars with it. It happened so fast that as the body of one of the cars fell, its roof tore off completely and landed on the embankment beyond the bridge. It was as if the roof kept going after the car dropped off of the bottom.

Any disaster brings great shock to a nation, or at least that area, and the suffering of the injured made it even worse. Some of the injured were impaled by splinters throughout their bodies and others were dismembered and yet others were badly mangled. As rescuers began their work, the very first body pulled from the wreck was a headless woman. It happens. A train wreck often mangles and dismembers bodies. There were also two young men who were pinned under a pile of rubble. A car stove full of glowing coals hung over them. Somehow, the doors of the stove stayed closed, and the bolts held it firmly in place. Strange things like that happen sometimes too. Those men were rescued. Somehow, they got a second chance.

So, how was fraud to blame, you might ask. In the aftermath, investigators found that the iron bridge design was quite poor. The bridge was never strong enough to carry the load of the rail traffic it had to serve. When they looked at the materials and the design, it was obvious. They also looked at the designer, Edmund Hewins. Their investigation exposed Hewins as a fraud. To make matters worse, the railroad had failed to inspect and properly maintain the bridge, even though they found nuts and bolts that had fallen from the bridge and were lying on the street below. They knew there were problems, but nothing was done, and the…it was just too late.

Every time an airplane crashes, we expect the worst…multiple deaths, if not the death of everyone on board. Some crashes look so horrific that you wonder how anyone could possibly have lived. While dropping from the sky to land on the hard ground or even on water usually ends in devastation, once in a while, a miracle happens, and everyone on the plane walks away from the crash…everyone!! It can only be called a miracle crash.

Every time an airplane crashes, we expect the worst…multiple deaths, if not the death of everyone on board. Some crashes look so horrific that you wonder how anyone could possibly have lived. While dropping from the sky to land on the hard ground or even on water usually ends in devastation, once in a while, a miracle happens, and everyone on the plane walks away from the crash…everyone!! It can only be called a miracle crash.

These days, probably the most well-known “miracle crash” was the “Miracle on the Hudson” crash. Captain Sullenberger was an amazing pilot, and as a result, all 155 people walked away from what could have been a horrible crash. Some pilots might have even tried to make it back to the airport, flying over and crashing into the city buildings, but “Sully” knew that was impossible, so he did the only sensible thing and water landed into the Hudson River.

There have been a number of other “miracle crashes” throughout the history of aviation. Some in small planes,  but some in large commercial planes. It may not always be possible, but a good pilot has a much better chance of landing, or really crashing their airplane and being so successful at it, that everyone walks away. The passengers are likely to have a few injuries, but they are alive, and that is what matters.

but some in large commercial planes. It may not always be possible, but a good pilot has a much better chance of landing, or really crashing their airplane and being so successful at it, that everyone walks away. The passengers are likely to have a few injuries, but they are alive, and that is what matters.

German photographer Dietmar Eckell has made it his life’s work to find, what he calls “miracles in aviation history” at the abandoned sites of wrecks that have resulted in no casualties. Eckell’s photo-project, “Happy End” highlights 15 airplanes that had forced landings, in which all the people on board survived and were rescued from really remote locations. One thing I don’t always understand is that the planes are abandoned where they crashed. I suppose sometimes it is hard to recover them, and other times they have already been there for years, by the time they are located. I never knew how many planes litter the earth, both above and below the water, but there are many.

Two of the “miracle crashes” that Eckell photographed were the Douglas Skytrain C-47 that crashed in the  Yukon in Canada in February 1950 and the Avro Shackleton, that crashed in the Western Sahara in 1994. In the crash of the Douglas Skytrain, all 10 people aboard survived, even in the frigid conditions. With the Avro Shackleton, two engines of the plane suddenly failed, sending it down to the desert sand in 1994. Surviving this crash in such an inhospitable environment was an astonishing feat for the 19 passengers and crew. If it weren’t for Dietmar Eckell’s determination to search out and photograph these lost “miracle crash” sites, much of the history of these miracles might have been forgotten. I for one plane to look up his “Happy End” project to read more about the “miracle crashes” he found.

Yukon in Canada in February 1950 and the Avro Shackleton, that crashed in the Western Sahara in 1994. In the crash of the Douglas Skytrain, all 10 people aboard survived, even in the frigid conditions. With the Avro Shackleton, two engines of the plane suddenly failed, sending it down to the desert sand in 1994. Surviving this crash in such an inhospitable environment was an astonishing feat for the 19 passengers and crew. If it weren’t for Dietmar Eckell’s determination to search out and photograph these lost “miracle crash” sites, much of the history of these miracles might have been forgotten. I for one plane to look up his “Happy End” project to read more about the “miracle crashes” he found.

I woke up this morning to about three inches of snow, which has now turned into about twelve to fifteen inches. Spring officially started on March 20th, so my question is…WHY are we looking at so much snow!!! Businesses are closed, schools are on a homeschool day for today and tomorrow, and many of the roads are closed or have “No unnecessary travel” restrictions. I know Spring snowstorms are not that unusual, but I don’t have to like them. Ok, that’s my rant. This isn’t the first Spring snowstorm I’ve ever been through, and most likely won’t be the last. In fact, I remember a few from my childhood, that have been doozies!!

I woke up this morning to about three inches of snow, which has now turned into about twelve to fifteen inches. Spring officially started on March 20th, so my question is…WHY are we looking at so much snow!!! Businesses are closed, schools are on a homeschool day for today and tomorrow, and many of the roads are closed or have “No unnecessary travel” restrictions. I know Spring snowstorms are not that unusual, but I don’t have to like them. Ok, that’s my rant. This isn’t the first Spring snowstorm I’ve ever been through, and most likely won’t be the last. In fact, I remember a few from my childhood, that have been doozies!!

We had a storm in 1973, that totally qualifies as “a doozy” and one I’ll never forget. I had to get up on the roof of my parents’ house and shovel the snow off. The news told everyone that too much snow could cause the roof to collapse. That was the first I had ever heard of such a thing. These days, it’s common knowledge. Of course,

schools were closed with that storm too, and people were actually getting around on snowmobiles in town. I remember thinking ho strange that was. Still, there were people who needed to get places, and people with snowmobiles were helping them get there. I didn’t hear of any emergency childbirths with that storm, but I suppose it was possible.

schools were closed with that storm too, and people were actually getting around on snowmobiles in town. I remember thinking ho strange that was. Still, there were people who needed to get places, and people with snowmobiles were helping them get there. I didn’t hear of any emergency childbirths with that storm, but I suppose it was possible.

My niece, Chantel Balcerzak was just a teeny, little girl of two, and the snow was taller than she was. Of course, Chantel is only 4’10” now, so not much has changed, and she might want to stay indoors, so she doesn’t get lost. My dad, her grandpa, Al Spencer took her outside for a picture to commemorate the occasion. Like most snow days, the fre day presented us with a perfect opportunity for fun in the snow, and we took full advantage with snowball fights and trudging through the depths of the “white stuff” that covered the city. It’s funny how that snowstorm seemed so fun, and these days such a storm is just annoying.

I suppose things could be worse. I could be one of those

people who will lose wages due to businesses closing, or who have to figure out daycare for children who are now home from school, or who will have to figure out a way to get to work , because my job doesn’t close for snow. Since I am retired, I will just get cozy with a fire going, and watch some television…oh wait, the internet is down which means that my television, email, and internet aren’t working. Thankfully there is wi-fi, so at least there is my phone. That’s my day, I hope you all have a wonderful doozy of a snow day!!

people who will lose wages due to businesses closing, or who have to figure out daycare for children who are now home from school, or who will have to figure out a way to get to work , because my job doesn’t close for snow. Since I am retired, I will just get cozy with a fire going, and watch some television…oh wait, the internet is down which means that my television, email, and internet aren’t working. Thankfully there is wi-fi, so at least there is my phone. That’s my day, I hope you all have a wonderful doozy of a snow day!!

During World War II and really with any war, any coastal area of the United States had to be kept on a higher alert than during peacetime. Coastal defense networks now are much more technological that they were in 1943. During World War II, the West Coast was patrolled by units of men whose job it was to watch for activities that were out of the ordinary along the Olympic Coast of Washington. Normally, their job was pretty boring, unless you liked walking or driving along the coast looking at the ocean. There were ships out there, but most of them were where they were supposed to be and were not cause for concern.

During World War II and really with any war, any coastal area of the United States had to be kept on a higher alert than during peacetime. Coastal defense networks now are much more technological that they were in 1943. During World War II, the West Coast was patrolled by units of men whose job it was to watch for activities that were out of the ordinary along the Olympic Coast of Washington. Normally, their job was pretty boring, unless you liked walking or driving along the coast looking at the ocean. There were ships out there, but most of them were where they were supposed to be and were not cause for concern.

In the early spring of 1943, however, coastal lookout activities along the Olympic Peninsula suddenly took a turn from the mundane to something quite unusual. As the La Push unit patrolled the beach that day, they suddenly began to see debris on the beach. That is never a good thing to see, because it means that somewhere, there is a ship in a lot of trouble. Rain, wind, and heavy seas just before midnight on April 1st, were driving the Russian steamship Lamut toward the shoreline, and behind a jagged cluster of rocks just off Teahwhit Head. By the early morning hours of April 2nd, the ship was in great peril, and the lives of the crew hung in the balance.

The La Push patrol unit was in for an intense morning, as they would find at first light on April 2nd. When the  patrolmen began finding wreckage on the beach, they headed south along the beach to see if they might find the ship in trouble. It wasn’t long before they sighted part of the grounded ship. It was lodged between a hundred-foot cliff and a small, jagged rock island. Amazingly, there were survivors huddled high on the steeply sloping deck of the Russian ship called Lamut. They wouldn’t have lasted long on that deck, but the high seas made a sea rescue impossible. The coast guardsmen of the La Push Unit decided to attempt a rescue by land. That would be pretty treacherous in itself, but they had no other choice.

patrolmen began finding wreckage on the beach, they headed south along the beach to see if they might find the ship in trouble. It wasn’t long before they sighted part of the grounded ship. It was lodged between a hundred-foot cliff and a small, jagged rock island. Amazingly, there were survivors huddled high on the steeply sloping deck of the Russian ship called Lamut. They wouldn’t have lasted long on that deck, but the high seas made a sea rescue impossible. The coast guardsmen of the La Push Unit decided to attempt a rescue by land. That would be pretty treacherous in itself, but they had no other choice.

This would not be a quick rescue. By mid-morning, the members of the rescue party had cut a path through the thick underbrush bordering the beach. Then, they began their ascent along the slippery boulders to the top of the cliff above the smashed ship. They would have to get very creative in their rescue maneuvers. “Using gauze bandage weighted with a rock, a light line was lowered to the eager hands of the stranded crew aboard the Lamut. Tying heavier line to the gauze, one line succeeded another until a lifeline strong enough to support the weight of a single person was stretched between the ship and the cliff. One by one survivors were raised to the cliff top and finally assisted down the landward side of the rocky ridge to the beach below. As darkness approached, the last of the Lamut survivors emerged from the swampy beach trail to waiting coast guard trucks and ambulances.” The rescue of the Lamut crew was among the most dramatic events in the annals of World War II beach patrol history.

While this was just one of the rescues conducted by the Olympic Defense Network, it was undoubtedly the most intense rescue they performed in their years of service. On March 29, 1944, the beach patrol ended and a week

later the unit decommissioned. The trails in that area are now a part of the Olympic National Park probably date from the era of World War II beach patrol activities. A while back, a small, collapsed wood frame cabin was located at Teahwhit Head. It is believed to be associated with World War II beach patrolling activities in the La Push unit, and quite possibly belongs to the Lamut.

later the unit decommissioned. The trails in that area are now a part of the Olympic National Park probably date from the era of World War II beach patrol activities. A while back, a small, collapsed wood frame cabin was located at Teahwhit Head. It is believed to be associated with World War II beach patrolling activities in the La Push unit, and quite possibly belongs to the Lamut.