History

For most women, especially during the Revolutionary War era, life’s losses brought a long time of mourning, the wearing of black dresses, and times of reflection, before they eventually consider remarrying. For Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey, whose lifestyle earned her the name “Mad Anne” for her acts of bravery and heroism that were considered to be somewhat eccentric for a woman of her time, loss brought about quite the opposite reaction. Anne Hennis was born in Liverpool England in 1742. She was formally educated and learned to read and write. Her first experience with loss came before she turned 18. It is not known how they died, but both of Anne’s parents were gone before she turned 18, and she became an orphan. Life for Ann, who was poor and had a hard time earning enough money to survive, immediately became very hard. Anne had family near Staunton in the Shenandoah Valley, and when she was 19, she sailed to America to live with them. There, in 1765, she met and married Richard Trotter, a seasoned frontiersman and experienced soldier. The couple had one son named William.

For most women, especially during the Revolutionary War era, life’s losses brought a long time of mourning, the wearing of black dresses, and times of reflection, before they eventually consider remarrying. For Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey, whose lifestyle earned her the name “Mad Anne” for her acts of bravery and heroism that were considered to be somewhat eccentric for a woman of her time, loss brought about quite the opposite reaction. Anne Hennis was born in Liverpool England in 1742. She was formally educated and learned to read and write. Her first experience with loss came before she turned 18. It is not known how they died, but both of Anne’s parents were gone before she turned 18, and she became an orphan. Life for Ann, who was poor and had a hard time earning enough money to survive, immediately became very hard. Anne had family near Staunton in the Shenandoah Valley, and when she was 19, she sailed to America to live with them. There, in 1765, she met and married Richard Trotter, a seasoned frontiersman and experienced soldier. The couple had one son named William.

During the westward movement, when more and more people were heading west in search of land and adventure, fights began to break out between settlers and the Indians who had lived there for many years. The Governor of Virginia organized border militia to protect the settlers there. Richard Trotter joined this militia. On October 19, 1774, Shawnee Chief Cornstalk attacked the Virginia militia, hoping to halt their advance into the Ohio Country. This became known as the Battle of Point Pleasant. The battle raged on until Cornstalk finally retreated. The Virginians, along with a second force led by Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, then marched into the Ohio Country. Cornstalk had no choice but to agree to a treaty, ending the war. Many men on both sides lost their lives in the battle, including Richard Trotter.

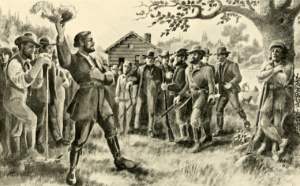

For Anne this could have meant years of sadness as a widow, but Anne would have none of that. Anne, upon learning of her husband’s death, and determined to seek revenge, left her young son in the care of neighbors, dressed in the clothing of a frontiersman, and set out to avenge her loss. A woman alone going out to kill the Indians seemed like an insane move to make, and most people probably thought she would be dead in a matter of days…but they didn’t know Anne. She became known as “Mad Anne” from that time forward….to whites and Indians alike. In the beginning, Anne rode from one recruiting station to another, asking them to volunteer their services to the militia in order to keep the women and children of the border safe, to fight for freedom from the Indians, and later the British.

People from Staunton, Virginia, to what is now Charleston, West Virginia, and Gallipolis, Ohio, knew Anne, mostly due to the unusual sight she presented. She usually wore buckskin leggings, petticoats, heavy brogan shoes, a man’s coat and hat, a hunting knife in a belt around her waist, and a rifle slung over her shoulder…everything she needed to be in the pioneer spirit in the late 1700s. Although Mad Anne mostly rode up and down the western frontier, she also recruited for the Continental Army, and delivered messages between various Army detachments during the Revolutionary War. It seemed that there was no job she wouldn’t take, including traveling as a courier on horseback between Forts Savannah and Randolph, a distance of almost 160 miles. Her fearless personality made her well known and respected by the settlers along the route. Mad Anne  was even respected, or maybe feared is a better word, by the Shawnee Indians. On her rides Bailey often came across a particular group of Shawnee Indians. They often chased her, then on one such encounter, she had had enough. Just when she was about to be caught, she jumped off her horse and hid in a log. Strangely, the Shawnee looked everywhere for her and even stopped to rest on the log, but they could not find her. Finally, they gave up and stole her horse. She waited a while after they left, and then came out of the log. She waited until nightfall, then crept into their camp and retrieved her horse…a bold move, but nothing like the next move she made. Once she was far enough away, she started screaming and shrieking at the top of her lungs. Now waking up to that would be shocking enough, but this woman was acting totally crazy, and the Shawnee thought she was possessed and therefore could not be injured by a bullet or arrow. After that display, the Shawnee saw her often, but the kept far away from her, because they were totally afraid of her. With that assurance backing her, Mad Anne knew that she was relatively safe living in the woods.

was even respected, or maybe feared is a better word, by the Shawnee Indians. On her rides Bailey often came across a particular group of Shawnee Indians. They often chased her, then on one such encounter, she had had enough. Just when she was about to be caught, she jumped off her horse and hid in a log. Strangely, the Shawnee looked everywhere for her and even stopped to rest on the log, but they could not find her. Finally, they gave up and stole her horse. She waited a while after they left, and then came out of the log. She waited until nightfall, then crept into their camp and retrieved her horse…a bold move, but nothing like the next move she made. Once she was far enough away, she started screaming and shrieking at the top of her lungs. Now waking up to that would be shocking enough, but this woman was acting totally crazy, and the Shawnee thought she was possessed and therefore could not be injured by a bullet or arrow. After that display, the Shawnee saw her often, but the kept far away from her, because they were totally afraid of her. With that assurance backing her, Mad Anne knew that she was relatively safe living in the woods.

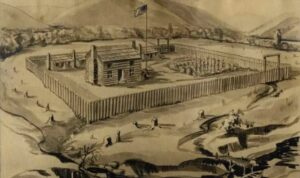

Anne met John Bailey, a member of a legendary group of frontier scouts called the Rangers, after several years living on her own. The Rangers were defending the Roanoke and Catawba settlements from Indian attacks. He was rather smitten with Mad Anne’s rough ways, and they were married November 3, 1785. In 1787, along the Kanawha River at the mouth of the Elk River, a blockhouse was built. The block house would later become Fort Lee in honor of Virginia’s Governor Henry Lee. Fort Lee was where John Bailey was assigned to duty, taking with him his now famous, gun-toting, hard-riding bride.

In 1788, John Bailey was transferred to Fort Clendenin, which was a more active area of conflict between the settlers and Native Americans. Anne Bailey began working for the settlers as well, riding on horseback to warn them of impending attacks. In 1791, she singlehandedly saved Fort Lee from certain destruction by hostile Indians with a three-day, 200–mile round trip to replenish their supply of gunpowder. She rode for hours, finally reaching Fort Savannah at Lewisburg, where the gunpowder was quickly packed aboard her horse and one additional mount, before she reversed her direction and galloped full speed back to Fort Lee.

After she returned, the siege was ended, the attackers were defeated. For her bravery Anne was given the horse that had carried her away and brought her safely back. The animal was said to have been a beautiful black, sporting white feet and a blazed face. She dubbed him Liverpool, in honor of her birthplace. Anne Bailey was forty-nine years old when she made this famous ride. Anne became a legend among the other settlers, and she was always welcome in their homes. John Bailey died in 1802, and Anne decided that she no longer wanted to live in a house, so she lived in the wilderness for over 20 years. She visited friends in town occasionally, but usually slept outside. Her favorite place was a cave near Thirteen Mile Creek.

A widow for the second time, and in her late fifties, Anne later went to live with her son, but her love for riding and of the wilderness had not ceased. For many years afterwards she could be seen riding from Point Pleasant to Lewisburg and Staunton, carrying mail and as an express messenger. Bailey continued working as a messenger,  bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. She finally retired in 1817 after making one last trip to Charleston at age 75. In 1818 Anne moved with her son and his family to his new farm in Gallia County, Ohio. Instead of asking her to stay with his family, her son, who had apparently never felt any ill-will toward his mother who was often not around, built her a cabin nearby so she would still feel independent. Bailey continued working as a messenger, bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey died at Gallipolis, Ohio, November 22, 1825, at the age of 83. She was buried in the Trotter Graveyard near her son’s home, and her remains rested there for seventy-six years. On October 10, 1901, her remains were re-interred in Monument Park in Point Pleasant, under the auspices of the Colonel Charles Lewis, Jr. Chapter of the D. A. R.

bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. She finally retired in 1817 after making one last trip to Charleston at age 75. In 1818 Anne moved with her son and his family to his new farm in Gallia County, Ohio. Instead of asking her to stay with his family, her son, who had apparently never felt any ill-will toward his mother who was often not around, built her a cabin nearby so she would still feel independent. Bailey continued working as a messenger, bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey died at Gallipolis, Ohio, November 22, 1825, at the age of 83. She was buried in the Trotter Graveyard near her son’s home, and her remains rested there for seventy-six years. On October 10, 1901, her remains were re-interred in Monument Park in Point Pleasant, under the auspices of the Colonel Charles Lewis, Jr. Chapter of the D. A. R.

It’s strange to think that someone would build a ship for the sole purpose of freezing it in the Artic ice sheet as a way of “floating” it over the North Pole, but that was exactly the plan when a ship named Fram (meaning Forward) was designed and built by the Scottish-Norwegian shipwright Colin Archer. The ship was built for Fridtjof Nansen’s 1893 Arctic expedition, to actually freeze it in the polar ice. The ship was a special design to be used in expeditions of the Arctic and Antarctic regions by the Norwegian explorers Fridtjof Nansen, Otto Sverdrup, Oscar Wisting, and Roald Amundsen between 1893 and 1912. Nansen’s ambition was to explore the Arctic farther north than anyone else, but he knew that they would be dealing with a problem that many sailing on the polar ocean had encountered before him, a problem that ended their expeditions…the freezing ice could crush a ship and end the expedition. The ship that was going to survive freezing in the Artic ice sheet, would have to be different…in just about every way. Nansen’s idea was to build a ship that could survive the pressure of the ice, not because it was stronger, but because it’s very shape would let the ice push the ship up, so it would actually “float” on top of the ice.

It’s strange to think that someone would build a ship for the sole purpose of freezing it in the Artic ice sheet as a way of “floating” it over the North Pole, but that was exactly the plan when a ship named Fram (meaning Forward) was designed and built by the Scottish-Norwegian shipwright Colin Archer. The ship was built for Fridtjof Nansen’s 1893 Arctic expedition, to actually freeze it in the polar ice. The ship was a special design to be used in expeditions of the Arctic and Antarctic regions by the Norwegian explorers Fridtjof Nansen, Otto Sverdrup, Oscar Wisting, and Roald Amundsen between 1893 and 1912. Nansen’s ambition was to explore the Arctic farther north than anyone else, but he knew that they would be dealing with a problem that many sailing on the polar ocean had encountered before him, a problem that ended their expeditions…the freezing ice could crush a ship and end the expedition. The ship that was going to survive freezing in the Artic ice sheet, would have to be different…in just about every way. Nansen’s idea was to build a ship that could survive the pressure of the ice, not because it was stronger, but because it’s very shape would let the ice push the ship up, so it would actually “float” on top of the ice.

Fram is a three-masted schooner with a total length of 127 feet 11 inches and width of 36 feet 1 inch. The ship was designed to be both unusually wide and unusually shallow in order to better withstand the forces of pressing ice. By design it would be able to push up through the ice to the top of the ice sheet, thereby allowing  it to float. Fram’s outer layer was made of, which can withstand the ice. It also had almost no keel so it could handle the shallow waters Nansen expected to encounter. The ship was designed with a retractable rudder and propeller, and it was carefully insulated to allow the crew to live on board for up to five years. A windmill was installed to run a generator that would provide electric power for lighting by electric arc lamps. The ship was launched on 26 October 1892. During the initial building process, Fram was fitted with a steam engine, which was fine, until something better came along. Then, before Amundsen’s expedition to the South Pole in 1910, the engine was replaced with a diesel engine, a first for polar exploration vessels.

it to float. Fram’s outer layer was made of, which can withstand the ice. It also had almost no keel so it could handle the shallow waters Nansen expected to encounter. The ship was designed with a retractable rudder and propeller, and it was carefully insulated to allow the crew to live on board for up to five years. A windmill was installed to run a generator that would provide electric power for lighting by electric arc lamps. The ship was launched on 26 October 1892. During the initial building process, Fram was fitted with a steam engine, which was fine, until something better came along. Then, before Amundsen’s expedition to the South Pole in 1910, the engine was replaced with a diesel engine, a first for polar exploration vessels.

Because of wreckage found at Greenland from USS Jeannette, which was lost off Siberia, and driftwood found in the regions of Svalbard and Greenland, Nansen had a theory that an ocean current flowed beneath the Arctic ice sheet from east to west, bringing driftwood from the Siberian region to Svalbard and further west. That was the main reason for building Fram. He wanted to order to explore this theory. His expedition ended up lasting three years, during which time, Nansen realized that Fram would not reach the North Pole directly. The current either wasn’t strong enough, or the polar ice was actually on land at the North Pole. So, he and Hjalmar Johansen set out to reach it on skis. After reaching 86° 14′ north, he had to turn back to spend the winter at Franz Joseph Land. During their expedition, Nansen and Johansen survived on walrus and polar bear meat and blubber. Finally, after they met up with British explorers from the Jackson-Harmsworth Expedition, they arrived back in Norway only days before the Fram also returned there. Their skiing mission was far more successful than the Fram’s mission, as the ship had spent nearly three years trapped in the ice, after only reaching 85° 57′ N. Fram made a scientific expedition to the Canadian Artic Archipelago between 1892 and 1902, and after being fitted with the diesel engine, Amundsen made his South Pole expedition from 1910 to 1912. Fram was

the first ship to reach the South Pole, during which Fram reached 78° 41′ S.

the first ship to reach the South Pole, during which Fram reached 78° 41′ S.

Following these expeditions, Fram was left to decay in storage from 1912 until the late 1920s. Then, Lars Christensen, Otto Sverdrup, and Oscar Wisting decide to begin an effort to preserve it by starting the Fram Committee. Finally, the now restored ship was installed in the Fram Museum in 1945, where it now stands.

Hiking and Backpacking have been a favorite pastime for many people for many years, and some people go to greater lengths and distances than others. Backpacking in Australia is a trip on the bucket lists of a lot of people. On their hikes, many people have made the Childers Palace Backpackers Hostel one of their stops. Located in the former Palace Hotel in the town of Childers, Queensland, Australia, the building had been converted into a backpacker hostel. That was the stop for 15 backpackers on June 22, 2000. They had been hiking all day and were ready for some downtime. After a relaxed evening, they all went to bed. There were 88 people staying in the building that night, but the building could house 101 people.

Hiking and Backpacking have been a favorite pastime for many people for many years, and some people go to greater lengths and distances than others. Backpacking in Australia is a trip on the bucket lists of a lot of people. On their hikes, many people have made the Childers Palace Backpackers Hostel one of their stops. Located in the former Palace Hotel in the town of Childers, Queensland, Australia, the building had been converted into a backpacker hostel. That was the stop for 15 backpackers on June 22, 2000. They had been hiking all day and were ready for some downtime. After a relaxed evening, they all went to bed. There were 88 people staying in the building that night, but the building could house 101 people.

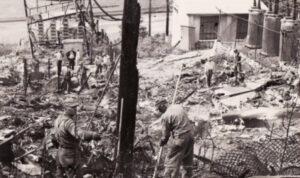

At about 12:30am on June 23, 2000, a fire started in the downstairs recreation room and quickly spread up the walls and into the stairwell. The first emergency call came from a pay phone across the street, and it was logged at 12:31am. Emergency services first arrived at 12:38am and spent four hours battling the fire before it was fully extinguished. In the aftermath, it was found that 15 backpackers, nine women and six men, had lost their lives. Survivors told of how smoke quickly filled the area and how the building’s power was lost. They struggled in the darkness to find a way out, and in the absence of alarms and emergency lighting, some people attempted to awaken and rescue as many people as they could. Of the 70 backpackers who survived the fire, 10 suffered minor burns and injuries as they tried to escape from the upper level and by jumping onto the roofs of the neighboring buildings. In this fire, those who got out lived, those who died did not get out at all.

Of the 15 who died in the fire, seven were British, three were Australian, two were from the Netherlands, and one each from Ireland, Japan, and South Korea. It took a while to identify the dead, because there was an incomplete hostel register. It recorded check-ins, but unfortunately not departures. To further complicate things, most of the residents’ passports were destroyed or damaged by the fire. DNA samples were also difficult to obtain for those with no relatives in Australia. Most of the backpackers who died were on the first floor of the hostel. Through an inquest, it was found that in one of the upper rooms where 10 victims were found, which was all of the occupants of that room, a bunk bed blocked a fastened exit door, and the windows were barred. They had little chance of escape.

It was found that a fruit packer named Robert Paul Long, had moved into the hostel on March 24, 2000, but had been evicted on June 14, 2000, over a matter of $200 rent in arrears. Long didn’t leave the area, as was seen in ATM records that showed him in the area in the week before the fire. Long, who had expressed a hatred of backpackers, had also earlier threatened to burn down the hostel. Around midnight, prior to the fire, two guests saw Long in the back yard of the hostel. Long had asked them to leave the door open so he could assault his former roommate, an Indian national. They declined, and he told them that he still had a key. Another guest recounted how he had woken up around midnight to find Long downstairs using a PC near a burning rubbish bin. After the guest protested the reckless actions, Long took the bin outside, and the guest went back to bed, but was awakened later to banging sounds, shouting, and thick black smoke.

After the fire, Long tried to mask his movements, but he was later spotted in cane-fields about five days later. At that time, he was arrested in bush-land near Howard, which is less than 20 miles from Childers. As he was being arrested, Long stabbed a police dog after being bitten. Then, he stabbed one of the officers in the jaw and the second officer shot Long in the shoulder. In March of 2002, Long was found guilty of two charges of murder (for the dead Australian twins) and arson and sentenced to life in prison. While it seems strange to only charge him with the deaths of two of the 15 victims, it was thought that it would expedite the proceedings and to allow for other charges to be brought in the event of an acquittal. Following his conviction, Long filed an appeal in 2002, which was denied. In June 2020 he became eligible for parole, but his February 2021 parole appeal was rejected. He could become eligible again in 1 year.

After the fire, and many people losing everything they owned, survivors were temporarily housed locally at the Isis Cultural Centre. Japan’s embassy officials quickly evacuated five Japanese nationals, which eased things a little. Residents of Childers knitted blankets and donated food and backpacks for the survivors. Residents also invited survivors for meals and showers and local businesses assisted with food, clothing, and personal items. Media, politicians, and investigators came to the site as well and Princess Anne visited on July 2nd, to meet the surviving backpackers and others involved in the disaster.

The results of a coronial inquest were released in 2006. “The hostel, a 98-year-old, two-story timber building, did not have working smoke detectors or fire alarms. It was later reported that the owner had installed fire alarms in the building, but they had been disabled weeks prior to the fire due to regular malfunctioning. It was also mentioned that batteries for the stand-alone alarms were sometimes removed by customers for portable cameras or music players.” When it was announced that the coroner had decided not to charge the owner and operators of the hostel for negligence, families of seven victims filed a class action suit against them.

On October 26, 2002, the renovated structure, renamed the Palace Memorial Building, opened and the opening ceremony was attended by some 250 invited guests, including members of 12 of the families of those who died. Frank Slarke, the father of the dead Australian twins, read a poem he wrote as a eulogy. Since then, over one million visitors have visited the building.

On October 26, 2002, the renovated structure, renamed the Palace Memorial Building, opened and the opening ceremony was attended by some 250 invited guests, including members of 12 of the families of those who died. Frank Slarke, the father of the dead Australian twins, read a poem he wrote as a eulogy. Since then, over one million visitors have visited the building.

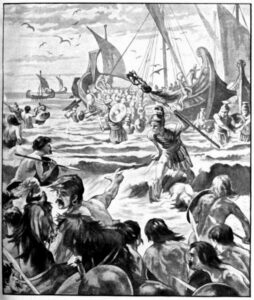

Before Julius Caesar invaded Britain, many Romans didn’t believe it existed. Julius Caesar was the first-ever Roman to invade Britain. He did it twice in the years 55 and 54 BC. Some Romans believed Britain to be just the foot of another huge northern continent. Others thought it was a place full of unbelievable riches, whilst most thought it just didn’t exist.

Before Julius Caesar invaded Britain, many Romans didn’t believe it existed. Julius Caesar was the first-ever Roman to invade Britain. He did it twice in the years 55 and 54 BC. Some Romans believed Britain to be just the foot of another huge northern continent. Others thought it was a place full of unbelievable riches, whilst most thought it just didn’t exist.

In the course of his Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar invaded Britain twice: in 55 and 54 BC. On the first occasion Caesar took with him only two legions and achieved little beyond a landing on the coast of Kent. The second invasion consisted of 628 ships, five legions and 2,000 cavalry. The Roman legion is the largest military unit of the Roman army,  comprised 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of the Roman Empire (27 BC – AD 476). Caesar’s force was so overwhelming that the Britons did not dare contest Caesar’s landing in Kent, waiting instead until he began to move inland. Caesar’s forces eventually made their way into Middlesex and crossed the Thames, forcing the British warlord Cassivellaunus to surrender, after which Caesar set up Mandubracius of the Trinovantes as client king, basically a sub king. As with all conquerors, Caesar included the accounts of both invasions in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico, with the first significant first-hand description of the people, culture, and geography of the island.

comprised 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of the Roman Empire (27 BC – AD 476). Caesar’s force was so overwhelming that the Britons did not dare contest Caesar’s landing in Kent, waiting instead until he began to move inland. Caesar’s forces eventually made their way into Middlesex and crossed the Thames, forcing the British warlord Cassivellaunus to surrender, after which Caesar set up Mandubracius of the Trinovantes as client king, basically a sub king. As with all conquerors, Caesar included the accounts of both invasions in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico, with the first significant first-hand description of the people, culture, and geography of the island.

Caesar’s writings are thought to be the start of the written history or at least the protohistory of Britain.

Caesar’s writings are thought to be the start of the written history or at least the protohistory of Britain.

It seems odd to me to think that people could simply not think that Britain exists, but I suppose that in a huge part of our world’s history, and actually still with some people today, it was thought that the Earth is flat, meaning that the horizon we see is all there is. If that is your mindset, it would be easy to limit the Earth to the horizon we can see, but it would not be an assumption that would be based on fact. Now with satellites and airplanes we know that the Earth is definitely round, just like the Bible and most people have said. And that said, we know that Britain existed long before the men of Caesar’s time found and invaded.

Normally, on this first day of Summer, I would be thinking about the days coming up, the precious few days when I finally get to feel the warmth that doesn’t come from being wrapped in a blanket or wearing a coat. Yes, Summer can be sweltering, and I can find myself wishing for a little cooler temperature, but I don’t want it to be much cooler. I am a summer person. I like heat. I like wearing shorts and sandals, rather than sweaters and coats.

Normally, on this first day of Summer, I would be thinking about the days coming up, the precious few days when I finally get to feel the warmth that doesn’t come from being wrapped in a blanket or wearing a coat. Yes, Summer can be sweltering, and I can find myself wishing for a little cooler temperature, but I don’t want it to be much cooler. I am a summer person. I like heat. I like wearing shorts and sandals, rather than sweaters and coats.

This year is a rather odd year…not that we haven’t had years of unusual weather…and no, I don’t buy into the whole global warming, climate change, or whatever they are calling it these days. Weather had natural patterns that have existed since time began, and this is nothing new. Nevertheless, when we have one of those years of an unusually cold Spring, and unusually harsh Winter, and somehow a fairly normal Fall, I find myself waiting for normalcy, impatiently!!

This has been one of those years, and I’m ready for the end of Spring. Our Winter was harsh, with lots of snow and this Spring has been full of thunderstorms and pouring rain…to the point of flash flooding and lots of warnings for lightning, hail, tornadoes, and floods. Those things aren’t all that unusual, with the possible exception of the floods, but the thing I really noticed was the cold temperatures. Normally as we approach the end of June, I am wearing shorts and t-shirts when I go out for my early morning walk. This year, however, I have been wearing pants and a jacket to keep me warm. Of course, by the time I am almost finished, I’m warm enough to go without a jacket…except for the clouds. Clouds just keep things cooler.

This has been one of those years, and I’m ready for the end of Spring. Our Winter was harsh, with lots of snow and this Spring has been full of thunderstorms and pouring rain…to the point of flash flooding and lots of warnings for lightning, hail, tornadoes, and floods. Those things aren’t all that unusual, with the possible exception of the floods, but the thing I really noticed was the cold temperatures. Normally as we approach the end of June, I am wearing shorts and t-shirts when I go out for my early morning walk. This year, however, I have been wearing pants and a jacket to keep me warm. Of course, by the time I am almost finished, I’m warm enough to go without a jacket…except for the clouds. Clouds just keep things cooler.

As I was walking these past few mornings, I thought about just how much cooler it had been this Spring, and I hoped that as the Summer arrived, it would finally begin to warm up. I also thought about another Summer about 20 years ago or so. The Spring had been cold that year too, and Summer hadn’t improved much. In fact, it was the coldest Summer I had ever remembered. Infact, it was as if Summer never arrived that year. That makes for the feeling of a long cold Winter, even though there were some warm days. The good thing about the colder rainy weather, however, was that the grass, and several other things grew better that they had in years. I guess that’s a plus, but if you don’t mind, I’ll take the warmer weather, with the leaves on the trees and the deer by the trail. Those things make my whole day.

As I was walking these past few mornings, I thought about just how much cooler it had been this Spring, and I hoped that as the Summer arrived, it would finally begin to warm up. I also thought about another Summer about 20 years ago or so. The Spring had been cold that year too, and Summer hadn’t improved much. In fact, it was the coldest Summer I had ever remembered. Infact, it was as if Summer never arrived that year. That makes for the feeling of a long cold Winter, even though there were some warm days. The good thing about the colder rainy weather, however, was that the grass, and several other things grew better that they had in years. I guess that’s a plus, but if you don’t mind, I’ll take the warmer weather, with the leaves on the trees and the deer by the trail. Those things make my whole day.

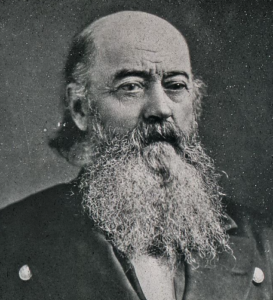

Joe Meek was born in Virginia in 1810. He was a friendly young man, with a great sense of humor, but he had too much rambunctious energy to do well in school. He just couldn’t sit still well enough to focus on his studies. Finally, at 16 years old and illiterate, Meek gave up on school and moved west to join two of his brothers in Missouri. Still, he didn’t give up on all of his learning, just the formal learning. In later years, he taught himself to read and write, but his spelling and grammar remained “highly original” throughout his life.

Joe Meek was born in Virginia in 1810. He was a friendly young man, with a great sense of humor, but he had too much rambunctious energy to do well in school. He just couldn’t sit still well enough to focus on his studies. Finally, at 16 years old and illiterate, Meek gave up on school and moved west to join two of his brothers in Missouri. Still, he didn’t give up on all of his learning, just the formal learning. In later years, he taught himself to read and write, but his spelling and grammar remained “highly original” throughout his life.

Meek seemed to flourish in the West. It appears that he had found his calling, and in early 1829, he joined William Sublette’s ambitious expedition to begin fur trading in the Far West. Meek traveled throughout the West for the next decade. For him there was nothing greater than the adventure and independence of the mountain man life. Meek, the picture of a mountain man, at 6 feet 2 inches tall, and heavily bearded became a favorite character at the annual mountain-men rendezvous. The others loved to listen to his humorous and often exaggerated stories of his wilderness adventures. The truth is, I’m sure many people would have loved to hear about the adventures of the mountain man, especially this one, who was so unique. Like most mountain men, Meek was a renowned grizzly bear hunter. I suppose his stories of his hunting escapades could have been exaggerations, it’s hard to say. Meek claimed he liked to “count coup” on the dangerous animals before killing them, a variation on a Native American practice in which they shamed a live human enemy by tapping them with a long stick. To tap a grizzly bear with a stick, before the attempted kill, took either courage…or stupidity. Meek also claimed that he had wrestled an attacking grizzly with his bare hands before finally sinking a tomahawk into its brain. I suppose that if a grizzly bear attacked you, you would have no choice but to fight for your life, with your bare hands. Having the forethought to go for your tomahawk would be…well, amazing. Most people would try to cover their heads, and hope for the best. Still, that wouldn’t do much good. In a bear attack, you had better fight with everything you have, if you want to live. Maybe  mountain men spent a lot of time considering the possibility of an attack, and practicing in their head exactly how they would handle it.

mountain men spent a lot of time considering the possibility of an attack, and practicing in their head exactly how they would handle it.

Meek soon established good relations with many Native Americans, effectively melding with the Indians. He even married three Native American women, including the daughter of a Nez Perce chief. Now, that didn’t mean that he didn’t fight with the tribes on occasion, or at least the tribes who were hostile to the incursion of the mountain men into their territories. Meek intended to fight for his right to be on the land, the same as the Indians. In the spring of 1837, Meek was nearly killed by a Blackfeet warrior who was taking aim with his bow while Meek tried to reload his Hawken rifle. In the end, the warrior nervously dropped his first arrow while drawing the bow, and Meek had time to reload and shoot. The warrior’s fumble cost him his life, while saving Meek’s life.

After a great run as a mountain man, Meek recognized that the golden era of the free trappers was coming to a close. He began making plans to find another form of income. He joined with another mountain man, and along with his third wife, he guided one of the first wagon trains to cross the Rockies on the Oregon Trail. Once he arrived in Oregon, Meek fell in love with the lush Willamette Valley of western Oregon. He settled down and became a farmer, and actively encouraged other Americans to join him. Of course, more White men on what had been Indian lands, came with safety issued. Meek led a delegation to Washington DC to ask for military protection from Native American attacks and territorial status for Oregon in 1847. Though he arrived “ragged,  dirty, and lousy,” Meek became a bit of a celebrity in the capitol. Not used to the ways of mountain men, the Easterners truly enjoyed the rowdy good humor Meek showed in proclaiming himself the “envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary from the Republic of Oregon to the Court of the United States.” His enthusiasm prompted Congress to making Oregon an official American territory and Meek a US marshal. I wonder if he was shocked by his new role.

dirty, and lousy,” Meek became a bit of a celebrity in the capitol. Not used to the ways of mountain men, the Easterners truly enjoyed the rowdy good humor Meek showed in proclaiming himself the “envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary from the Republic of Oregon to the Court of the United States.” His enthusiasm prompted Congress to making Oregon an official American territory and Meek a US marshal. I wonder if he was shocked by his new role.

He might have been shocked, but Meek embraced his new role. He returned to Oregon and became heavily involved in politics, eventually founded the Oregon Republican Party. After his years of service, he retired to his farm, and on June 20, 1875, at the age of 65, Meek passed away. With his passing the world lost a skilled practitioner of the frontier art of the tall tale. It is said that his life was nearly as adventurous as his stories claimed, but there is no sure line to tell what was real and what was tall tale.

As the United States was being settled, a number of wars were fought between the Native Americans and the White Man. So much anger and so many hard feelings had passed between the two groups that it seemed like peace could never be achieved. Finally, in an attempt to convince local Native Americans to make peace with the United States, the Jesuit missionary Pierre-Jean De Smet met with the Sioux leader Sitting Bull in what is present-day Montana. He saw an urgent need to make peace and decided to go for it.

As the United States was being settled, a number of wars were fought between the Native Americans and the White Man. So much anger and so many hard feelings had passed between the two groups that it seemed like peace could never be achieved. Finally, in an attempt to convince local Native Americans to make peace with the United States, the Jesuit missionary Pierre-Jean De Smet met with the Sioux leader Sitting Bull in what is present-day Montana. He saw an urgent need to make peace and decided to go for it.

De Smet was a native of Belgium, who came to the United States in 1821 at the age of 20. Once in the states, he became a novice of the Jesuit order in Maryland. De Smet was ordained in Saint Louis, and as a priest, decided to be a missionary to the Native Americans of the Far West. It was an ambitious goal, but in 1838, he was sent to evangelize the Potawatomi villages near present-day Council Bluffs, Iowa. De Smet met a delegation of Flathead Indians there. The Indians had come east looking for a “black robe” whom they hoped might be able to aid their tribe. Of course, a “black robe” would be a priest, and since De Smet was indeed a priest, they had found what they were looking for. De Smet worked with the Flathead Indians several times during the 1840s in present-day western Montana. While there, he established a mission and actually secured a peace treaty with the Blackfeet, who had previously been the irreconcilable enemy of the Flathead.

His hard work earned De Smet a reputation as a white man who could be trusted to negotiate disputes between Native Americans and the US government, which was not something that very many people could boast. The disputes between the Indians and the US government became fairly commonplace in the West during the 1860s. The Plains Indians, like the Sioux and Cheyenne resisted the growing flood of white settlers invading their territories and killing their game animals. As the conflicts continued, the US government began to demand  that all the Plains Indians be relocated to reservations, another source of contention. The leaders in the American government and military had hoped that the relocation could be achieved through negotiations, but in the absence of a peaceful relocation, they were perfectly willing to use violence to force the local Native Americans to comply. It was futile to fight the change, but anyone can see why the Native Americans would try. They didn’t want to be forced to stay in just one area and to be told what they could and could not do…and in reality, the reservations have not proven to be the best thing for either side. Nevertheless, that is where we are today, and in many ways, the situation hasn’t improved much, except there aren’t Indian wars, so I guess that is a good thing. The disputes are handled differently now, but the feeling of a nation inside a nation is one that really isn’t perfect. Still, the Indian Nation does exist inside the United States, and they do have jurisdiction in their own territory, and I don’t suppose the feeling of separation will ever change.

that all the Plains Indians be relocated to reservations, another source of contention. The leaders in the American government and military had hoped that the relocation could be achieved through negotiations, but in the absence of a peaceful relocation, they were perfectly willing to use violence to force the local Native Americans to comply. It was futile to fight the change, but anyone can see why the Native Americans would try. They didn’t want to be forced to stay in just one area and to be told what they could and could not do…and in reality, the reservations have not proven to be the best thing for either side. Nevertheless, that is where we are today, and in many ways, the situation hasn’t improved much, except there aren’t Indian wars, so I guess that is a good thing. The disputes are handled differently now, but the feeling of a nation inside a nation is one that really isn’t perfect. Still, the Indian Nation does exist inside the United States, and they do have jurisdiction in their own territory, and I don’t suppose the feeling of separation will ever change.

While flight remains one of the safest forms of travel, there is always the possibility of a malfunction that can have devastating effects. In the case of United Airlines Flight 624, a Douglas DC-6 airliner, registration NC37506, was a scheduled passenger flight from San Diego, California to New York City. Very likely, these passengers had taken this exact same flight a number of times, and possibly on this exact same plane. Nevertheless, this flight was about to be very different…and that difference was going to have devastating effects on the plane and on the outcome of this flight.

While flight remains one of the safest forms of travel, there is always the possibility of a malfunction that can have devastating effects. In the case of United Airlines Flight 624, a Douglas DC-6 airliner, registration NC37506, was a scheduled passenger flight from San Diego, California to New York City. Very likely, these passengers had taken this exact same flight a number of times, and possibly on this exact same plane. Nevertheless, this flight was about to be very different…and that difference was going to have devastating effects on the plane and on the outcome of this flight.

Flight 624 took off from Lindbergh Field, in what appeared to be a normal flight. The flight made its first scheduled stop at Los Angeles Airport, followed by a normal scheduled stop at Chicago Municipal Airport. Everything was normal for both stops. In fact, the  whole flight proceeded normally until they began their descent into New York’s LaGuardia Airport. They began their descent over Pennsylvania, and suddenly, they had a warning alarm telling them of a fire in the cargo hold. The crew responded to what was later determined to be a false signal of a fire in the front cargo hold by releasing CO2. Proper operating procedure called for opening the cabin pressure relief valves prior to discharging the CO2 bottles, to allow for venting of the CO2 gas buildup in the cabin and cockpit. There was no evidence found of the crew opening the relief valves. Either they forgot or it malfunctioned (which didn’t appear to be the case). As a result, the released CO2 gas seeped back into the cockpit from the front cargo hold and apparently

whole flight proceeded normally until they began their descent into New York’s LaGuardia Airport. They began their descent over Pennsylvania, and suddenly, they had a warning alarm telling them of a fire in the cargo hold. The crew responded to what was later determined to be a false signal of a fire in the front cargo hold by releasing CO2. Proper operating procedure called for opening the cabin pressure relief valves prior to discharging the CO2 bottles, to allow for venting of the CO2 gas buildup in the cabin and cockpit. There was no evidence found of the crew opening the relief valves. Either they forgot or it malfunctioned (which didn’t appear to be the case). As a result, the released CO2 gas seeped back into the cockpit from the front cargo hold and apparently  partially incapacitated the flight crew. It would be like being in a closed-up garage and leaving your car running. The decision-making process of the crew became compromised. As things got worse, the crew put the aircraft into an emergency descent, miscalculating their altitude, and as the plane descended lower than it should have, it hit a high-voltage power line and burst into flames. The plane then smashed through the trees of a wooded hillside about five miles from Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania, a small town 135 miles from Philadelphia, at 1:41pm EDT on June 17, 1948. When the four-engined, propeller-driven airplane crashed, it resulted in the deaths of all four crew members and 39 passengers on board.

partially incapacitated the flight crew. It would be like being in a closed-up garage and leaving your car running. The decision-making process of the crew became compromised. As things got worse, the crew put the aircraft into an emergency descent, miscalculating their altitude, and as the plane descended lower than it should have, it hit a high-voltage power line and burst into flames. The plane then smashed through the trees of a wooded hillside about five miles from Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania, a small town 135 miles from Philadelphia, at 1:41pm EDT on June 17, 1948. When the four-engined, propeller-driven airplane crashed, it resulted in the deaths of all four crew members and 39 passengers on board.

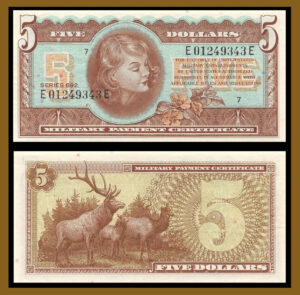

During World War II, and through the Vietnam War, the United States government was facing a situation with the US dollar that was different from prior years. It’s not something we really think about much, but it had to do with the fact that the countries the US Military was in were unsure of how their money was going to play out if they were one of the countries that fell. The dollar was stable, so they were happy to take payment in the US dollar over their own currency. In fact, the local civilians often accepted payment in dollars for less than the accepted conversion rates, meaning that they lost money in the deal. Dollars became more favorable to hold, which further inflated the local currencies, defeating plans to stabilize local economies. On top of that, troops were being paid in dollars, which they could

During World War II, and through the Vietnam War, the United States government was facing a situation with the US dollar that was different from prior years. It’s not something we really think about much, but it had to do with the fact that the countries the US Military was in were unsure of how their money was going to play out if they were one of the countries that fell. The dollar was stable, so they were happy to take payment in the US dollar over their own currency. In fact, the local civilians often accepted payment in dollars for less than the accepted conversion rates, meaning that they lost money in the deal. Dollars became more favorable to hold, which further inflated the local currencies, defeating plans to stabilize local economies. On top of that, troops were being paid in dollars, which they could  convert in unlimited amounts to the local currency with merchants at the floating (black market) conversion rate, which was much more than the government fixed conversion rate. It was rather a great money-making proposition, but really wasn’t ethical. This conversion rate imbalance allowed the servicemen to profit from the more favorable exchange rate.

convert in unlimited amounts to the local currency with merchants at the floating (black market) conversion rate, which was much more than the government fixed conversion rate. It was rather a great money-making proposition, but really wasn’t ethical. This conversion rate imbalance allowed the servicemen to profit from the more favorable exchange rate.

While anyone could understand how people would want to make money if they can, it was really going to be damaging to the local economy in the end. The MPCs were designed to stop the unfair conversion rate of currency. The scrip (MOCs) was changed out periodically, to avoid hoarding. Once they came out with a new version of scrip, the prior version became worthless. Another way they were supposed to eliminate the problem was that MPCs were only allowed to be used by military personnel in military facilities and approved locations. As a safeguard, if the MPCs  were converted to local currency, they were not allowed to be reconverted to MPCs, so the plan was useless. US MPCs were in use from 1946-1973 and were used in all overseas military locations.

were converted to local currency, they were not allowed to be reconverted to MPCs, so the plan was useless. US MPCs were in use from 1946-1973 and were used in all overseas military locations.

I was actually watching an episode of MASH this morning about this very thing. The men were buying up the old scrip from people who couldn’t get to the exchange. Of course, they bought it for less than its value, planning to cash in when they turned it in for its face value. The solution for that problem was that the military personnel were restricted to the base on C-Days…currency exchange days. I don’t know how much of the fraudulent exchanges were stopped in this way, but it might have stopped some.

It’s not often that a young man “pulls strings” in order to go to war. Most men would rather not go to war, and some will even try to “pull strings” to get out of going. John F Kennedy, who had some health problems, and an old back injury from his college football days, was turned down for the Navy, but his dad managed to pull some strings for his son, who really wanted to go into the navy. Young was desperate, and like most parents, his father wanted to help fulfill that dream. So in 1941, Kennedy’s politically connected father, Joseph Kennedy used his influence to get his sin, John “Jack” into the service. Of course, Joseph might have been thinking ahead to future political maneuvers when he pushed for a military career for his son. Once in the Navy, Kennedy volunteered for PT (motorized torpedo) boat duty in the Pacific in 1942.

It’s not often that a young man “pulls strings” in order to go to war. Most men would rather not go to war, and some will even try to “pull strings” to get out of going. John F Kennedy, who had some health problems, and an old back injury from his college football days, was turned down for the Navy, but his dad managed to pull some strings for his son, who really wanted to go into the navy. Young was desperate, and like most parents, his father wanted to help fulfill that dream. So in 1941, Kennedy’s politically connected father, Joseph Kennedy used his influence to get his sin, John “Jack” into the service. Of course, Joseph might have been thinking ahead to future political maneuvers when he pushed for a military career for his son. Once in the Navy, Kennedy volunteered for PT (motorized torpedo) boat duty in the Pacific in 1942.

“Jack” Kennedy quickly worked to move himself up in rank, and soon he was Lieutenant John F. Kennedy. July 1943 found Lieutenant Kennedy and the crew of PT 109 in combat near the Solomon Islands. People often think that being in the Navy or the Air Force is somehow safer than the Army or Marines, but the reality is that any position in a war

can prove to be dangerous. On August 2, 1943, the middle of the night, Kennedy’s boat was rammed by a Japanese destroyer and caught fire. In the ensuing explosion, several of Kennedy’s shipmates were blown overboard into a sea of burning oil. With no regard for his own life, Kennedy dove in to rescue three of the crew and in the process swallowed some of the toxic mixture. Kennedy always blamed his chronic stomach problems on that incident. The ordeal was not quickly over, and for 12 hours, Kennedy and his men clung to the wrecked hull. Finally, he ordered them to abandon ship. Kennedy and the other good swimmers placed the injured on a makeshift raft. They took turns pushing and towing the raft four miles to safety on a nearby island.

can prove to be dangerous. On August 2, 1943, the middle of the night, Kennedy’s boat was rammed by a Japanese destroyer and caught fire. In the ensuing explosion, several of Kennedy’s shipmates were blown overboard into a sea of burning oil. With no regard for his own life, Kennedy dove in to rescue three of the crew and in the process swallowed some of the toxic mixture. Kennedy always blamed his chronic stomach problems on that incident. The ordeal was not quickly over, and for 12 hours, Kennedy and his men clung to the wrecked hull. Finally, he ordered them to abandon ship. Kennedy and the other good swimmers placed the injured on a makeshift raft. They took turns pushing and towing the raft four miles to safety on a nearby island.

Their ordeal still wasn’t over. For six days, Kennedy and his crew waited on the island for rescue. There was little to eat on the island, but the men survived by drinking coconut milk and rainwater until native islanders discovered the sailors and offered food and shelter. While they waited, Kennedy tried every night to signal other US Navy ships in the area. In addition, Kennedy scrawled a message on a coconut husk and gestured to the islanders to take it to a nearby PT base at Rendova. Finally, on August 8, a Navy patrol boat picked up the survivors of PT-109.

The men were taken to the hospital to recuperate, and on June 12, 1944, while Kennedy was in the hospital recuperating from back surgery, he received the Navy and Marine Corps medal for “courage, endurance, and

excellent leadership [that] contributed to the saving of several lives and was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

excellent leadership [that] contributed to the saving of several lives and was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Of course, the rest is history. John F Kennedy went on to become the 35th President of the United States, and on November 22, 1963, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. His vice president, Lyndon B Johnson, assumed the presidency upon Kennedy’s death.