History

I love old military sites, like forts, and from one to another, they are so many differences. In Casper, Wyoming, where I live, Fort Caspar is a typical Old West fort as you would expect of the days of wagon trains and Indian rampages, but when you look at a fort back east and especially along coastal waters, where it would be necessary to protect our borders, they are much more military looking. Fort Gaines, located the eastern tip of Dauphin Island, off the Gulf coast of Alabama, is a very different looking fort, as my mind pictures forts anyway. Fort Gaines’ well-preserved ramparts, which have guarded the entrance to Mobile Bay for more than 150 years, look very much like they did when they were first built there. The structure is considered one of the nation’s best-preserved Civil War era masonry forts. However, it is also under threat from erosion, as is common of very old structures. The present Fort Gaines was initially designed in 1818 as the identical twin to Fort Morgan, which stands across Mobile Bay, to defend the new territory of Alabama. It was named for General Edmund Pendleton Gaines, a hero of the War of 1812. However, when Congress cancelled funding in 1821, work on the fort was suspended. Years later, when more funding became available 1846, the original design was scrapped, and when construction began in 1857 a new pentagonal-shaped design took its place. The objective of the fortress was to guard the seaward approaches to Mobile Bay and the eastern entrance of the Mississippi Sound.

I love old military sites, like forts, and from one to another, they are so many differences. In Casper, Wyoming, where I live, Fort Caspar is a typical Old West fort as you would expect of the days of wagon trains and Indian rampages, but when you look at a fort back east and especially along coastal waters, where it would be necessary to protect our borders, they are much more military looking. Fort Gaines, located the eastern tip of Dauphin Island, off the Gulf coast of Alabama, is a very different looking fort, as my mind pictures forts anyway. Fort Gaines’ well-preserved ramparts, which have guarded the entrance to Mobile Bay for more than 150 years, look very much like they did when they were first built there. The structure is considered one of the nation’s best-preserved Civil War era masonry forts. However, it is also under threat from erosion, as is common of very old structures. The present Fort Gaines was initially designed in 1818 as the identical twin to Fort Morgan, which stands across Mobile Bay, to defend the new territory of Alabama. It was named for General Edmund Pendleton Gaines, a hero of the War of 1812. However, when Congress cancelled funding in 1821, work on the fort was suspended. Years later, when more funding became available 1846, the original design was scrapped, and when construction began in 1857 a new pentagonal-shaped design took its place. The objective of the fortress was to guard the seaward approaches to Mobile Bay and the eastern entrance of the Mississippi Sound.

Dauphin Island was used for centuries by the Native Americans, who went there to fish, hunt, and gather oysters and other shellfish that grew in abundance in Mobile Bay. To this day, evidence of their presence can  still be seen at Shell Mound Park on the Island’s north shore. The island was also visited by Italian explorer Americus Vespucius, who is said to have visited in 1497. In addition, the Spanish discovered the island, which they named Isle de Labe (Island of the Ridge) from the large sand dunes that extend along its southern shores. The French took possession in 1699 the French and renamed it the Isle de Massacre, because they found so many skeletons scattered on the beach that they thought a massacre had taken place there. The French established a settlement on the island that was raided by pirates in 1711, but survived.

still be seen at Shell Mound Park on the Island’s north shore. The island was also visited by Italian explorer Americus Vespucius, who is said to have visited in 1497. In addition, the Spanish discovered the island, which they named Isle de Labe (Island of the Ridge) from the large sand dunes that extend along its southern shores. The French took possession in 1699 the French and renamed it the Isle de Massacre, because they found so many skeletons scattered on the beach that they thought a massacre had taken place there. The French established a settlement on the island that was raided by pirates in 1711, but survived.

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the French Governor, built a fort there that’s he called Fort Torabigbee and changed the name of the island to Dauphin Island after a member of French royalty, “Dauphine” about 1712. From 1763 to 1783, the English held this Island, and in 1783 it went back to Spain. Finally, after years of dispute as to ownership, in 1812, Dauphin Island was taken by the United States during the War of 1812 because it was said the Spanish sympathized with the English. The earliest American fortification built here was in 1812, and that area has belonged to the United States since that time.

Before the fort was fully completed, the Alabama state militia seized it on January 5, 1861, because they were anticipating the state seceding from the Union. That did occur on January 11, 1861. Following the secession, Confederate engineers completed the fort over the next several years. During the Civil War, the fort played an vital role in the Battle of Mobile Bay, and it was within sight of its walls that Union Admiral David G Farragut issued his immortal command, “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!” After Farragut and his ships forced their way into the bay, Union soldiers laid siege to Fort Gaines, which surrendered on August 8, 1864. After the Union forces took possession of the fort, it was used to plan and stage the final attack on Mobile, Alabama.

Following the Civil War, the fort was repaired by engineers, but the post stood empty for years. Between 1901  and 1904, two modern gun batteries were built. These housed six guns that complemented the modernizations at nearby Fort Morgan. Other than the basic preservation repairs, Fort Gaines was not further improvements. Fort Gaines, like its sister complex, Fort Morgan and other forts, was no longer needed for harbor defense, as its guns were outmatched by those on foreign battleships. When World War I ended the War Department sold Fort Gaines to the state of Alabama, however it was reactivated briefly during World War II and then returned to the state once again. The state opened Fort Gaines as a state park in 1955. Fort Gaines is currently under the management of the Dauphin Island Park and Beach Board.

and 1904, two modern gun batteries were built. These housed six guns that complemented the modernizations at nearby Fort Morgan. Other than the basic preservation repairs, Fort Gaines was not further improvements. Fort Gaines, like its sister complex, Fort Morgan and other forts, was no longer needed for harbor defense, as its guns were outmatched by those on foreign battleships. When World War I ended the War Department sold Fort Gaines to the state of Alabama, however it was reactivated briefly during World War II and then returned to the state once again. The state opened Fort Gaines as a state park in 1955. Fort Gaines is currently under the management of the Dauphin Island Park and Beach Board.

When we think of the Gold Rush years, most of us think of California, but in reality, not every big strike was in California. One of the greatest gold rushes of North America occurred in the Pike’s Peak area. Known as the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, it was also called the Colorado Gold Rush. The Pike’s Peak Gold Rush a boom in gold prospecting and mining in the Pike’s Peak area of what was then the western Kansas Territory and southwestern Nebraska Territory of the United States. Now it is located in Colorado, of course. The rush began in July 1858 and lasted until just about the time of the creation of the Colorado Territory on February 28, 1861. The rush brought an estimated 100,000 gold seekers, called the Fifty-Niners to the Pike’s Peak area. It was part of one of the greatest gold rushes in North American history.

When we think of the Gold Rush years, most of us think of California, but in reality, not every big strike was in California. One of the greatest gold rushes of North America occurred in the Pike’s Peak area. Known as the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, it was also called the Colorado Gold Rush. The Pike’s Peak Gold Rush a boom in gold prospecting and mining in the Pike’s Peak area of what was then the western Kansas Territory and southwestern Nebraska Territory of the United States. Now it is located in Colorado, of course. The rush began in July 1858 and lasted until just about the time of the creation of the Colorado Territory on February 28, 1861. The rush brought an estimated 100,000 gold seekers, called the Fifty-Niners to the Pike’s Peak area. It was part of one of the greatest gold rushes in North American history.

The peak year for the gold rush was 1859, and so after that year, the miners were called Fifty-Niners. The miners often used the motto “Pike’s Peak or Bust!” Actually, the location of the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush was centered 85 miles north of Pike’s Peak, but because of the well-known mountain, and its visibility from a long way off, the name of the peak became the name of the rush. The Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, began about a decade after the California Gold Rush, and produced a dramatic, albeit temporary influx of migrants and immigrants into the Pike’s Peak Country of the Southern Rocky Mountains. When the rush ended many of them moved on to other placed in search o the next big rush. The prospectors provided the first major European-American population in the region. The rush brought with it a few mining camps such as Denver City and Boulder City that would actually develop into cities that still exist today. Many smaller camps such as Auraria and Saint Charles City were among those that were later absorbed by larger camps and towns. Still others, faded into ghost towns, but quite a few camps such as Central City, Black Hawk, Georgetown, and Idaho Springs survived.

The discovery of gold in the Pike’s Peak area wasn’t a surprise to everyone. In 1835, French trapper Eustace Carriere lost his party and ended up wandering through the mountains for many weeks. During those weeks he  found many gold specimens which he later took back to New Mexico for examination. I suppose it was worth being lost, but while the specimens turned out to be “pure gold” he was unable to locate the area on an expedition he led to go back and look for it. He just couldn’t quite remember the location. Also, in 1849 and 1850, several parties of gold seekers bound for the California Gold Rush panned small amounts of gold from various streams in the South Platte River valley at the foot of the Rocky Mountains. They decided that they weren’t really impressed with the Rocky Mountain gold, so they moved on to California, possibly cheating themselves out of a great find, had the persevered.

found many gold specimens which he later took back to New Mexico for examination. I suppose it was worth being lost, but while the specimens turned out to be “pure gold” he was unable to locate the area on an expedition he led to go back and look for it. He just couldn’t quite remember the location. Also, in 1849 and 1850, several parties of gold seekers bound for the California Gold Rush panned small amounts of gold from various streams in the South Platte River valley at the foot of the Rocky Mountains. They decided that they weren’t really impressed with the Rocky Mountain gold, so they moved on to California, possibly cheating themselves out of a great find, had the persevered.

When the California Gold Rush began to die out, many discouraged gold seekers started to return home. Still, they weren’t really wanting to go home empty-handed, and they has heard the rumors of gold in the Pike’s Peak area. So, they tried their luck again, and their hard work paid off. In the summer of 1857, a party of Spanish-speaking gold seekers from New Mexico worked a placer deposit along the South Platte River about 5 miles above Cherry Creek, now part of metropolitan Denver.

William Greeneberry “Green” Russell was a Georgian man who had worked in the California gold fields in the 1850s. He was married to a Cherokee woman, and through his connections to the tribe, he heard about an 1849 discovery of gold along the South Platte River. Much encouraged, he organized a party to prospect along the South Platte River. He set out with his two brothers and six companions in February 1858. They met up with Cherokee tribe members along the Arkansas River in present-day Oklahoma and continued westward along the Santa Fe Trail. Others joined the party along the way until their number reached 107 people.

When you have spent any time in Colorado, the names of the places where gold was found are very real to you. Places like Cherry Creek, Denver, Confluence Park in Denver, Englewood, and a number of others stand out to you. The group finally found a small amount of 20 troy ounces in the Englewood area. Their excitement grew… and so the boom began. The first decade of the boom was largely concentrated along the South Platte River at the base of the Rocky Mountains, in the canyon of Clear Creek in the mountains west of Golden City, at Breckenridge and in South Park at Como, Fairplay, and Alma. The towns of Denver City, Golden City, and Boulder City were substantial towns that served the mines in 1860. It was the rapid population growth of the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush that led to the creation of the Colorado Territory in 1861. Unfortunately, the rush, like all gold rushes, faded and while Colorado is still a fairly large population area, it isn’t what it might have been had the gold rush continued.

and so the boom began. The first decade of the boom was largely concentrated along the South Platte River at the base of the Rocky Mountains, in the canyon of Clear Creek in the mountains west of Golden City, at Breckenridge and in South Park at Como, Fairplay, and Alma. The towns of Denver City, Golden City, and Boulder City were substantial towns that served the mines in 1860. It was the rapid population growth of the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush that led to the creation of the Colorado Territory in 1861. Unfortunately, the rush, like all gold rushes, faded and while Colorado is still a fairly large population area, it isn’t what it might have been had the gold rush continued.

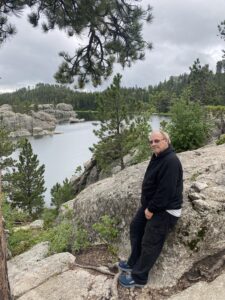

While my husband, Bob and I were in the Black Hills last week, we were having breakfast at the Hill City Cafe, when we overheard a waitress telling another table the story of how the Hill City High School came to have Smokey Bear as their mascot and be renamed the Hill City Rangers. I had no idea that anyone used Smokey Bear as their mascot, nor did I know that no other school was allowed to do so. That caught my interest, so we listened to the story, and then I had to research it further to get the whole story. And quite a story it is.

While my husband, Bob and I were in the Black Hills last week, we were having breakfast at the Hill City Cafe, when we overheard a waitress telling another table the story of how the Hill City High School came to have Smokey Bear as their mascot and be renamed the Hill City Rangers. I had no idea that anyone used Smokey Bear as their mascot, nor did I know that no other school was allowed to do so. That caught my interest, so we listened to the story, and then I had to research it further to get the whole story. And quite a story it is.

It all started around noon on July 10, 1939, with one of the worst forest fires in the history of the Black Hills. It was located just ten miles northwest of Hill City, and that’s too close for any wildfire to be to a city. Overnight, the fire burned through six of those ten miles, jumped the Mystic Road, the C.B. and Q. Railway, and was headed directly for Hill City. These are areas my husband, Bob and I have hiked, and hearing about the fire raging through them really hits home for me. The C.B. and Q Railway (Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad) was later abandoned and became the Mickelson Trail, which I have hiked from end to end, twice!! Not in one trip, but over about 10 years, one section at a time. The whole area is a place I love, and to think of it burning…well, it tears at my heart.

By noon on July 11, 1939, the fire was within three miles of town. That was when the wind changed and carried the fire further North and East. Still, Hill City and other towns were not safe, winds shift all the time, and the fire had to be stopped. The weather that year had been hot and very dry, unlike this year, plus a high wind repeatedly “crowned” the fire. The firefighters were in constant danger. They had already called in all of the Civilian Conservation Corps boys in the area, who had been immediately put on the fire, and now the forest rangers called for more help. You know that the situation is desperate, when they call for untrained volunteers. Shockingly, one of the first crews to respond was a group of 25 schoolboys from Hill City. These were high school kids…kids!! The crew of 25 included the entire basketball squad, one eighth grader, and several boys

who had recently attended or graduated from the Hill City High School. Their foreman was Charles Hare, President of the Board of Education. This whole story of bravery and selflessness brings tears to my eyes and puts a lump in my throat.

who had recently attended or graduated from the Hill City High School. Their foreman was Charles Hare, President of the Board of Education. This whole story of bravery and selflessness brings tears to my eyes and puts a lump in my throat.

The inferno raged throughout July 11th and into July 12th and utilized over four thousand firefighters, laboring together to bring the fire under control. The fire often isolated the crews, who went without food and water for a number of hours. Heat, smoke, and the danger of being trapped hampered the firefighters, but the blaze was brought under control on July 12th. The people of Hill City had spent many anxious hours watching the smoke and direction of the fire. Many had packed their belongings and were ready to move, but the order to abandon the town was never given. The schoolboys crew from Hill City was at the fire every day. The US Forest Service was so grateful to them that they were later recognized by officials as one of the best crews!! The McVey Fire burned over 20,000 acres.

To get back to the story the waitress was so proudly telling, “The name ‘Rangers’ was given to them in honor of their good record. Because of the work of these schoolboys back in 1939, Hill City Schools became the ONLY school district in the United States to have the privilege of using ‘Smokey Bear’ as its mascot. The school colors are Green and Gold which also represent the National Forest Service Theme, and Hill City is the ONLY school with the honorable privilege of having their graduation ceremonies held at Mount Rushmore. The staff, students and teams representing Hill City Schools hope to continue the traditions of the splendid group of men that our boys so ably assisted, The United States Forest Rangers.” It’s a proud tradition to own, and an awesome goal to

reach for. I’m sure they will be able to achieve their goal, and as an annual “tourist” in the area, who loves the Black Hills, I want to thank all the brave firefighters in the Black Hills-Hill City area…past, present, and future (one of which was my niece, Lindsay Moore, for a summer) for all their hard work keeping the area safe, and mostly for their bravery.

reach for. I’m sure they will be able to achieve their goal, and as an annual “tourist” in the area, who loves the Black Hills, I want to thank all the brave firefighters in the Black Hills-Hill City area…past, present, and future (one of which was my niece, Lindsay Moore, for a summer) for all their hard work keeping the area safe, and mostly for their bravery.

Hitler never had feeling of any kind toward mankind of any nationality, race, gender, or religion, even though there were those he hated more than others…specifically, Jews, Gypsies, Blacks, and anyone not blond haired and blue eyed. Nevertheless, Hitler had long ago decided that anyone was disposable, except him. He didn’t tell other people about that, of course. On July 8, 1941, the German army invaded Pskov, a city located 180 miles from Leningrad, Russia. General Franz Halder, the chief of the German army general staff recorded Hitler’s plans for Moscow and Leningrad in his diary, and it wasn’t good. Hitler planned “To dispose fully of their population, which otherwise we shall have to feed during the winter.” Basically, he considered them all to be “useless eaters” and planned to kill them. Then, he planned to turn Moscow into a lake.

Hitler never had feeling of any kind toward mankind of any nationality, race, gender, or religion, even though there were those he hated more than others…specifically, Jews, Gypsies, Blacks, and anyone not blond haired and blue eyed. Nevertheless, Hitler had long ago decided that anyone was disposable, except him. He didn’t tell other people about that, of course. On July 8, 1941, the German army invaded Pskov, a city located 180 miles from Leningrad, Russia. General Franz Halder, the chief of the German army general staff recorded Hitler’s plans for Moscow and Leningrad in his diary, and it wasn’t good. Hitler planned “To dispose fully of their population, which otherwise we shall have to feed during the winter.” Basically, he considered them all to be “useless eaters” and planned to kill them. Then, he planned to turn Moscow into a lake.

The Germans first launched a massive invasion of the Soviet Union, called Operation Barbarossa, on June 22, using over 3 million men. Since the Soviet army was unsuspecting and unprepared, the Germans were very successful in their attack. By July 8th, the Germans had captured more than 280,000 Soviet soldiers and almost 2,600 tanks had been destroyed. With the Germans already a couple of hundred miles inside Soviet territory, Stalin was in a state of panic. He began executing any of his generals who had failed to stop the advancing attack. That was likely a big mistake, because he was basically defeating himself from the inside.

As chief of staff, Halder had been keeping a diary of Hitler’s day-to-day decision-making process. His documentation of Hitler’s processes showed the flaws that Hitler had. I don’t know if that was his plan or if he had wanted to emulate Hitler, but as became emboldened by his successes in Russia, Halder recorded that the “Fuhrer is firmly determined to level Moscow and Leningrad to the ground.” It was Halder’s opinion that Hitler  had underestimated the Russian army’s numbers and the bitter infighting between factions within the military about strategy. Halder and several others thought they should head straight to Moscow, as taking the capital would bring down the entire country. Nevertheless, Hitler was the leader, and as such, he wanted to meet up with Field Marshal Wilhelm Leeb’s army group, which was making its way toward Leningrad. The biggest mistake Hitler made was the fact that Winter was coming, and the Russians were much more used to the Soviet Winter’s frigid temperatures than the Germans…an advantage that would eventually catch up to the Germans. The advantage of such conditions would give the Russians the victory over the Germans in this battle.

had underestimated the Russian army’s numbers and the bitter infighting between factions within the military about strategy. Halder and several others thought they should head straight to Moscow, as taking the capital would bring down the entire country. Nevertheless, Hitler was the leader, and as such, he wanted to meet up with Field Marshal Wilhelm Leeb’s army group, which was making its way toward Leningrad. The biggest mistake Hitler made was the fact that Winter was coming, and the Russians were much more used to the Soviet Winter’s frigid temperatures than the Germans…an advantage that would eventually catch up to the Germans. The advantage of such conditions would give the Russians the victory over the Germans in this battle.

Most people know that wine gets better with age, but I wonder if there is a limit to that statement. Some wines, I’m told wine can be aged for 10 to 20 years, but there really is a limit. In a Roman tomb in Germany in 1867, a bottle of wine was found that is believed to date back to 325 – 350 CE. The oldest bottle of wine ever found. Those who found it, named it Speyer, for the city of Speyer, near where the bottle was found. The bottle was discovered during an excavation of a 4th-century AD Roman nobleman’s tomb. The tomb contained two sarcophagi, one holding the body of a man and one a woman. It was a very unique bottle, with dolphin-shaped handles, and it is sealed with wax and olive oil. I’m sure that was the hope that by so preserving the wine, that it would be able to be used later, but then it was found in a tomb, so I’m not sure of the actual purpose. There were several other bottles found with the Speyer bottle, but they were all empty or broken.

Most people know that wine gets better with age, but I wonder if there is a limit to that statement. Some wines, I’m told wine can be aged for 10 to 20 years, but there really is a limit. In a Roman tomb in Germany in 1867, a bottle of wine was found that is believed to date back to 325 – 350 CE. The oldest bottle of wine ever found. Those who found it, named it Speyer, for the city of Speyer, near where the bottle was found. The bottle was discovered during an excavation of a 4th-century AD Roman nobleman’s tomb. The tomb contained two sarcophagi, one holding the body of a man and one a woman. It was a very unique bottle, with dolphin-shaped handles, and it is sealed with wax and olive oil. I’m sure that was the hope that by so preserving the wine, that it would be able to be used later, but then it was found in a tomb, so I’m not sure of the actual purpose. There were several other bottles found with the Speyer bottle, but they were all empty or broken.

Of course, given the age of the bottles, no one will ever drink the contents. It would not be safe, so the exact contents remain unknown. Nevertheless, archaeologists believe the liquid inside was made from grapes planted in the region. The Speyer wine bottle (Römerwein in German) is a sealed bottle that is will not been opened to check the contents. Even without verification, it is considered the world’s oldest known bottle of wine. Since the discovery of the bottle, it has been exhibited at the Wine Museum section of the Historical Museum of the Palatinate in Speyer. The “Römerwein” is housed in the museum’s Tower Room. It is a 51 US fluid ounce glass bottle with amphora-like “shoulders” that are yellow green in color and with dolphin-shaped handles.

It is thought that the man in the tomb was a Roman legionary, and the wine was a provision for his journey to  Heaven. People had some strange customs back then, and some may still have. Of the six glass bottles in the woman’s sarcophagus and the ten vessels in the man’s sarcophagus, only one still contained a liquid. There is a clear liquid in the bottom third, and a mixture similar to rosin above. While it has reportedly lost its ethanol content, analysis is consistent with at least part of the liquid having been wine, although I’m not sure how they made that analysis without opening the bottle. The wine was infused with a mixture of herbs, but the preservation of the wine is attributed to the large amount of thick olive oil. Since I’m not a scientist, I’m not sure how that would work, but apparently it did, as it was added to the bottle to seal the wine off from air, along with a hot wax seal. The use of glass in the bottle is unusual, however, as typically Roman glass was too fragile to be dependable over time.

Heaven. People had some strange customs back then, and some may still have. Of the six glass bottles in the woman’s sarcophagus and the ten vessels in the man’s sarcophagus, only one still contained a liquid. There is a clear liquid in the bottom third, and a mixture similar to rosin above. While it has reportedly lost its ethanol content, analysis is consistent with at least part of the liquid having been wine, although I’m not sure how they made that analysis without opening the bottle. The wine was infused with a mixture of herbs, but the preservation of the wine is attributed to the large amount of thick olive oil. Since I’m not a scientist, I’m not sure how that would work, but apparently it did, as it was added to the bottle to seal the wine off from air, along with a hot wax seal. The use of glass in the bottle is unusual, however, as typically Roman glass was too fragile to be dependable over time.

Scientists have considered opening the bottle to further analyze the contents, but as of 2023 the bottle has remained unopened, mostly because of concerns about how the liquid would react when exposed to air. The museum’s curator, Ludger Tekampe has stated he has seen no changes in the bottle in over 25 years, so whatever they are doing to preserve it is working. It seems to me that scientists would be remiss in their care of this bottle by opening it for no good reason. I think it should be left as is.

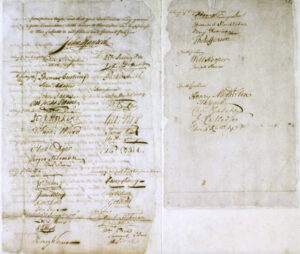

The American Revolutionary War actually began on April 19, 1775, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. At that time, it wasn’t considered a full-blown war, and attempts were still being made by July 5, 1775, to avoid that full-blown war. The Olive Branch Petition, adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 5, 1775, and signed on July 8th, was the final attempt to avoid the full-blown war between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies in America, that became known as the American Revolutionary War, and ended with full independence of the United States.

The American Revolutionary War actually began on April 19, 1775, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. At that time, it wasn’t considered a full-blown war, and attempts were still being made by July 5, 1775, to avoid that full-blown war. The Olive Branch Petition, adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 5, 1775, and signed on July 8th, was the final attempt to avoid the full-blown war between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies in America, that became known as the American Revolutionary War, and ended with full independence of the United States.

It seemed that in the early days of the Revolutionary War, the main weapon was a volley of petitions and proclamations. The Second Continental Congress had already authorized the invasion of Canada more than a week earlier, but the Olive Branch Petition affirmed American loyalty to Great Britain, asking King George III to prevent further conflict. The petition was followed up with a July 6th Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, making the success of the Olive Branch Petition unlikely in London. By August 1775, London officially declared the colonies to be in rebellion by the Proclamation of Rebellion, and the Olive Branch Petition was rejected by the British government. In fact, King George had refused to read it before declaring that the colonists were traitors.

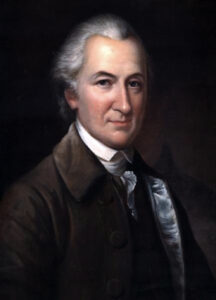

The Second Continental Congress convened in May 1775. At that time, most and most delegates followed John Dickinson in his quest to reconcile with King George. He could not picture a world with an independent United States. I suppose there are always those people without a vision for the future. However, there was a small group of delegates, led by John Adams, who could see that war was inevitable, and that we would need to become independent of Great Britain. Nevertheless, there is a right time, so they decided that the wisest course of action was to remain quiet and wait for the opportune time to rally the people. This allowed Dickinson and his followers to pursue their own course for a reconciliation that would ultimately never happen.

Dickinson was the primary author of the Olive Branch Petition, along with Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, John Rutledge, and Thomas Johnson, all of whom also served on the drafting committee. Dickinson claimed that the colonies did not want independence, but rather, wanted more equitable trade and tax regulations. He asked that the King establish a lasting settlement between the Mother Country and the colonies “upon so firm a basis as to perpetuate its blessings, uninterrupted by any future dissensions, to succeeding generations in both countries” beginning with the repeal of the Intolerable Acts. The introductory paragraph of the letter named twelve of the thirteen colonies, all except Georgia. The letter was approved on July 5 and signed by John Hancock, President of the Second Congress, and by representatives of the named twelve colonies. It was sent to London on July 8, 1775, in the care of Richard Penn and Arthur Lee. Dickinson hoped that news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord combined with the “humble petition” would persuade the King to respond with a counterproposal or open negotiations.

Finally, Adams wrote to a friend, telling him that the petition served no purpose. Everyone knew that war was inevitable. Adams said that the colonies should have already raised a navy and taken the British officials prisoner. Unfortunately, the letter was intercepted by British officials and news of its contents reached Great Britain at about the same time as the petition itself. British advocates of a military response used Adams’ letter to claim that the petition itself was insincere, and it was rejected. The hostilities which Adams had foreseen undercut the petition, and the King had answered it before it even reached him.

With the King’s refusal to consider the petition, came the opportunity Adams and others needed to push for independence. Now the colonists viewed the King as unwilling and uninterested concerning the colonists’ grievances. The colonists finally knew that they had just two choices…complete independence or complete submission to British rule. They chose complete independence, and the rest, as we all know, is history.

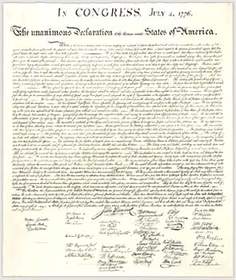

While Independence Day is celebrated on July 4th each year, with all the festivities, days off, barbecues, and fireworks, our nation…formally known as the thirteen colonies, actually obtained legal separation from Great Britain on July 2, 1776, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution of independence that had been proposed in June by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia declaring the United States independent from Great Britain’s rule. Called the Lee Resolution, it was also known as “The Resolution for Independence” and was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2nd. The Lee Resolution resolved that the Thirteen Colonies, at the time referred to as the United Colonies, were “free and independent states” and were now separate from the British Empire. The resolution created what became the United States of America.

While Independence Day is celebrated on July 4th each year, with all the festivities, days off, barbecues, and fireworks, our nation…formally known as the thirteen colonies, actually obtained legal separation from Great Britain on July 2, 1776, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution of independence that had been proposed in June by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia declaring the United States independent from Great Britain’s rule. Called the Lee Resolution, it was also known as “The Resolution for Independence” and was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2nd. The Lee Resolution resolved that the Thirteen Colonies, at the time referred to as the United Colonies, were “free and independent states” and were now separate from the British Empire. The resolution created what became the United States of America.

After passing the vote for independence, Congress could turn its attention to the Declaration of Independence, which would be the official statement explaining this decision. The Declaration of Independence had been prepared by a Committee of Five, with Thomas Jefferson as its principal author. While Jefferson collaborated extensively with the other four members of the Committee of Five, i,t was largely his writing and his wording that made up the Declaration of Independence. It was composed in isolation over 17 days between June 11, 1776, and June 28, 1776. Jefferson was renting the second floor of a three-story private home at 700 Market Street in Philadelphia at the time. The house, within walking distance of Independence Hall, is now known as the Declaration House.

Of course, as with any document brought before Congress, they debated and revised the wording of the Declaration, and for reasons unknown, removed wording in which Jefferson had vigorously denounced King George III for importing the slave trade. They finally approved the document two days later on July 4th. John

Adams wrote a letter to his wife, Abigail, on July 3rd, stating, “The second day of July 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.”

Adams wrote a letter to his wife, Abigail, on July 3rd, stating, “The second day of July 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.”

Of course, as we all know, Adams’s prediction was off by two days. Nevertheless, his idea that a day should be celebrated forever, did become a tradition, not on July 2nd, but rather on July 4th, because of the Declaration of Independence. That was because of the date shown on the much-publicized Declaration of Independence, rather than the date the resolution of independence was approved in a closed session of Congress. In addition, historians have disputed whether members of Congress signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, even though Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin all later wrote that they had signed it on that day. Many historians believe that the Declaration was signed nearly a month after its adoption, on August 2, 1776, and not on July 4th as many have believed. Nevertheless, they have been unable to prove their theory or to change the date on which we celebrate our independence.

One thing that I find very interesting is the fact that both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, who were the only two signatories of the Declaration of Independence later to serve as presidents of the United States, both

died on the same day…July 4, 1826, and within five hours of each other. They were also the last surviving members of the original American revolutionaries. It was also the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. James Monroe, while not a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, but who was another Founding Father who was elected president, also died on July 4, 1831, making him the third President who died on the anniversary of independence. There was one president who was born on Independence Day…Calvin Coolidge, who was born on July 4, 1872.

died on the same day…July 4, 1826, and within five hours of each other. They were also the last surviving members of the original American revolutionaries. It was also the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. James Monroe, while not a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, but who was another Founding Father who was elected president, also died on July 4, 1831, making him the third President who died on the anniversary of independence. There was one president who was born on Independence Day…Calvin Coolidge, who was born on July 4, 1872.

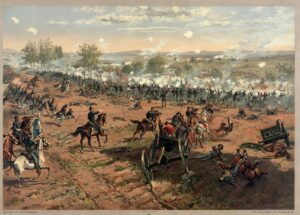

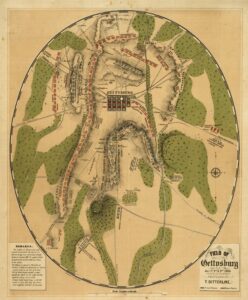

When things were heating up between the Confederate and Union soldiers around the town of Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, most of the town’s 2,400 civilian residents did their best to make themselves scarce. They didn’t want to find themselves pulled into the conflict on the basis of simply being in the vicinity when the Union needed reinforcements, so they did what they could to get out of the way…either staying shut up in their houses and basements or leaving for someplace calmer.

When things were heating up between the Confederate and Union soldiers around the town of Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, most of the town’s 2,400 civilian residents did their best to make themselves scarce. They didn’t want to find themselves pulled into the conflict on the basis of simply being in the vicinity when the Union needed reinforcements, so they did what they could to get out of the way…either staying shut up in their houses and basements or leaving for someplace calmer.

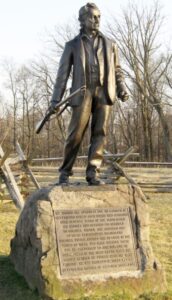

Not everyone felt that way, however. John Burns, who was about 69 years old at the time, although some said he was older, had fought a half-century earlier in the War of 1812. So, he was no stranger to war, but he took offence with the way a bunch of Rebels had come in and taken over his hometown. When he heard the sounds of battle on July 1, he told his wife he wanted to see what was going on. Grabbing his old flintlock musket, Burns left the house. He came across several Union officers and offered his services. The Union soldiers were basically amused by this strange character with his old musket, just showing up to offer to fight with them…and he wasn’t a young man, so that made it all the more strange. Still, Burns would not go away, and when he found a wounded soldier who would no longer need his rifle, Burns picked it up, and as the fighting heated up, Burns calmly took position behind a tree and began firing at the advancing Confederates. I guess the Union soldiers figured out pretty quickly that he meant business…especially when he was wounded three times in the intense fighting that day, and he still wouldn’t quit. One soldier recalled, “It must have been about noon when I saw a little old man coming up in the rear… I remember he wore a swallow-tailed coat with smooth brass buttons. He had a rifle on his shoulder. We boys began to poke fun at him as soon as he came amongst us, as we thought no civilian in his senses would [put] himself in such a place…”

The soldier then went on to say, “[When asked what] possessed him to come out there at such a time, he replied that ‘the rebels had either driven away or milked his cows, and that he was going to be even with them.’ About this time the enemy began to advance. Bullets were flying thicker and faster, and we hugged the ground about as close as we could. Burns got behind a tree and surprised us all by not taking a double-quick to the rear. He was as calm and collected as any veteran on the ground…I never saw John Burns after our movement to the right, when we left him behind his tree, and only know that he was true blue and grit to the backbone and fought until he was three times wounded.”

I’m sure it really upset the soldiers when they were forced to leave the injured Burns behind as they were ordered to retreat through the town. Burns was then found by the Confederates. Of course, since he had no uniform, they didn’t know that he wasn’t just a civilian who had been caught in the crossfire. Had they known he was fighting against them, they might have executed him, but a wise Burns had gotten rid of his weapon and pretended to be that helpless, unfortunate civilian who had been passing by at the wrong time. So, the Confederate surgeons treated him, and he was allowed to return home. The Confederates were none the wiser, and Burn had exacted his revenge. Burns was a happy man, because it just doesn’t get any better than that!!

So impressed were the Union soldiers with John Burns, that his story was told to their superiors, and Burns is now memorialized with a statue on the Gettysburg battlefield, and his valor was called out in an after-action report by Major General Abner Doubleday. The memorial reads: “My thanks are specially due to a citizen of Gettysburg named John Burns who although over 70 years of age shouldered his musket and offered his services to Colonel Wister, One Hundred and Fiftieth Pennsylvania Volunteers. Colonel Wister advised him to fight in the woods as there was more shelter there but he preferred to join our line of skirmishers in the open fields. When the troops retired he fought with the Iron Brigade. He was wounded in three places.” John Burns truly was a civilian hero, but the real moral of the story is “Don’t mess with the cows.”

So impressed were the Union soldiers with John Burns, that his story was told to their superiors, and Burns is now memorialized with a statue on the Gettysburg battlefield, and his valor was called out in an after-action report by Major General Abner Doubleday. The memorial reads: “My thanks are specially due to a citizen of Gettysburg named John Burns who although over 70 years of age shouldered his musket and offered his services to Colonel Wister, One Hundred and Fiftieth Pennsylvania Volunteers. Colonel Wister advised him to fight in the woods as there was more shelter there but he preferred to join our line of skirmishers in the open fields. When the troops retired he fought with the Iron Brigade. He was wounded in three places.” John Burns truly was a civilian hero, but the real moral of the story is “Don’t mess with the cows.”

Most of us don’t really think much about the possibility of a meteor hitting the Earth, and the reality is that it’s pretty rare…at least one of much size. Most of them burn up as they enter our atmosphere, and most often the ones that do hit are so small that they do little damage. The Tunguska event a definite exception to that rule. Coming in from the east-southeast, and at and incredible speed of about 60,000 miles per hour, but amazingly still not actually impacting the Earth, it was still classified as an impact event, even though no impact crater has been found. Instead, the object is thought to have disintegrated at an altitude of 3 to 6 miles above the surface, rather than actually impacting the Earth. The meteor did not simply fall apart or burn up, but rather it blew up in what was estimated as a 12-megaton explosion, near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River in Yeniseysk Governorate, which is now Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia, on the morning of June 30, 1908.

Most of us don’t really think much about the possibility of a meteor hitting the Earth, and the reality is that it’s pretty rare…at least one of much size. Most of them burn up as they enter our atmosphere, and most often the ones that do hit are so small that they do little damage. The Tunguska event a definite exception to that rule. Coming in from the east-southeast, and at and incredible speed of about 60,000 miles per hour, but amazingly still not actually impacting the Earth, it was still classified as an impact event, even though no impact crater has been found. Instead, the object is thought to have disintegrated at an altitude of 3 to 6 miles above the surface, rather than actually impacting the Earth. The meteor did not simply fall apart or burn up, but rather it blew up in what was estimated as a 12-megaton explosion, near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River in Yeniseysk Governorate, which is now Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia, on the morning of June 30, 1908.

The explosion was over the sparsely populated Eastern Siberian Taiga, which likely saved many lives, but  flattened an estimated 80 million trees over an area of 830 square miles of forest. The people who did witness the explosion, from a great distance, of course, reported that at least three people may have died in the event. The explosion is generally attributed to a meteor air burst, which is the atmospheric explosion of a stony asteroid approximately 160–200 feet in size. The Tunguska event remains the largest impact event on Earth in recorded history, though it is assumed that much larger impacts have occurred in times before history was recorded. An 12-megaton explosion could destroy a large city. Of course, events like this and even smaller ones have caused scientists to attempt to figure out ways to avoid these “direct hits” in the future…a rather large job, since moving the Earth out of the way of asteroids is really not an option.

flattened an estimated 80 million trees over an area of 830 square miles of forest. The people who did witness the explosion, from a great distance, of course, reported that at least three people may have died in the event. The explosion is generally attributed to a meteor air burst, which is the atmospheric explosion of a stony asteroid approximately 160–200 feet in size. The Tunguska event remains the largest impact event on Earth in recorded history, though it is assumed that much larger impacts have occurred in times before history was recorded. An 12-megaton explosion could destroy a large city. Of course, events like this and even smaller ones have caused scientists to attempt to figure out ways to avoid these “direct hits” in the future…a rather large job, since moving the Earth out of the way of asteroids is really not an option.

The Tunguska Event was a mystery for some time, after locals reported hearing a shattering explosion. Upon  investigation, it was found that trees were charred and leveled, and also that seismic waves were felt traveling through Europe. There are still some questions concerning the event, but it is widely believed to have been a comet colliding with Earth’s atmosphere. It is estimated that the explosion occurred 15,000-30,000 feet above the surface of the Earth. That explains the fact that no impact crater was found, still one would expect an explosion of that magnitude to trigger a massive fire. It did not, causing scientists to speculate that the subsequent blast wave doused the flames. Still, the massive amount of energy expelled by the blast is estimated to have been stronger than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

investigation, it was found that trees were charred and leveled, and also that seismic waves were felt traveling through Europe. There are still some questions concerning the event, but it is widely believed to have been a comet colliding with Earth’s atmosphere. It is estimated that the explosion occurred 15,000-30,000 feet above the surface of the Earth. That explains the fact that no impact crater was found, still one would expect an explosion of that magnitude to trigger a massive fire. It did not, causing scientists to speculate that the subsequent blast wave doused the flames. Still, the massive amount of energy expelled by the blast is estimated to have been stronger than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

For most women, especially during the Revolutionary War era, life’s losses brought a long time of mourning, the wearing of black dresses, and times of reflection, before they eventually consider remarrying. For Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey, whose lifestyle earned her the name “Mad Anne” for her acts of bravery and heroism that were considered to be somewhat eccentric for a woman of her time, loss brought about quite the opposite reaction. Anne Hennis was born in Liverpool England in 1742. She was formally educated and learned to read and write. Her first experience with loss came before she turned 18. It is not known how they died, but both of Anne’s parents were gone before she turned 18, and she became an orphan. Life for Ann, who was poor and had a hard time earning enough money to survive, immediately became very hard. Anne had family near Staunton in the Shenandoah Valley, and when she was 19, she sailed to America to live with them. There, in 1765, she met and married Richard Trotter, a seasoned frontiersman and experienced soldier. The couple had one son named William.

For most women, especially during the Revolutionary War era, life’s losses brought a long time of mourning, the wearing of black dresses, and times of reflection, before they eventually consider remarrying. For Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey, whose lifestyle earned her the name “Mad Anne” for her acts of bravery and heroism that were considered to be somewhat eccentric for a woman of her time, loss brought about quite the opposite reaction. Anne Hennis was born in Liverpool England in 1742. She was formally educated and learned to read and write. Her first experience with loss came before she turned 18. It is not known how they died, but both of Anne’s parents were gone before she turned 18, and she became an orphan. Life for Ann, who was poor and had a hard time earning enough money to survive, immediately became very hard. Anne had family near Staunton in the Shenandoah Valley, and when she was 19, she sailed to America to live with them. There, in 1765, she met and married Richard Trotter, a seasoned frontiersman and experienced soldier. The couple had one son named William.

During the westward movement, when more and more people were heading west in search of land and adventure, fights began to break out between settlers and the Indians who had lived there for many years. The Governor of Virginia organized border militia to protect the settlers there. Richard Trotter joined this militia. On October 19, 1774, Shawnee Chief Cornstalk attacked the Virginia militia, hoping to halt their advance into the Ohio Country. This became known as the Battle of Point Pleasant. The battle raged on until Cornstalk finally retreated. The Virginians, along with a second force led by Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, then marched into the Ohio Country. Cornstalk had no choice but to agree to a treaty, ending the war. Many men on both sides lost their lives in the battle, including Richard Trotter.

For Anne this could have meant years of sadness as a widow, but Anne would have none of that. Anne, upon learning of her husband’s death, and determined to seek revenge, left her young son in the care of neighbors, dressed in the clothing of a frontiersman, and set out to avenge her loss. A woman alone going out to kill the Indians seemed like an insane move to make, and most people probably thought she would be dead in a matter of days…but they didn’t know Anne. She became known as “Mad Anne” from that time forward….to whites and Indians alike. In the beginning, Anne rode from one recruiting station to another, asking them to volunteer their services to the militia in order to keep the women and children of the border safe, to fight for freedom from the Indians, and later the British.

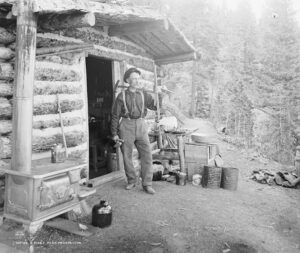

People from Staunton, Virginia, to what is now Charleston, West Virginia, and Gallipolis, Ohio, knew Anne, mostly due to the unusual sight she presented. She usually wore buckskin leggings, petticoats, heavy brogan shoes, a man’s coat and hat, a hunting knife in a belt around her waist, and a rifle slung over her shoulder…everything she needed to be in the pioneer spirit in the late 1700s. Although Mad Anne mostly rode up and down the western frontier, she also recruited for the Continental Army, and delivered messages between various Army detachments during the Revolutionary War. It seemed that there was no job she wouldn’t take, including traveling as a courier on horseback between Forts Savannah and Randolph, a distance of almost 160 miles. Her fearless personality made her well known and respected by the settlers along the route. Mad Anne  was even respected, or maybe feared is a better word, by the Shawnee Indians. On her rides Bailey often came across a particular group of Shawnee Indians. They often chased her, then on one such encounter, she had had enough. Just when she was about to be caught, she jumped off her horse and hid in a log. Strangely, the Shawnee looked everywhere for her and even stopped to rest on the log, but they could not find her. Finally, they gave up and stole her horse. She waited a while after they left, and then came out of the log. She waited until nightfall, then crept into their camp and retrieved her horse…a bold move, but nothing like the next move she made. Once she was far enough away, she started screaming and shrieking at the top of her lungs. Now waking up to that would be shocking enough, but this woman was acting totally crazy, and the Shawnee thought she was possessed and therefore could not be injured by a bullet or arrow. After that display, the Shawnee saw her often, but the kept far away from her, because they were totally afraid of her. With that assurance backing her, Mad Anne knew that she was relatively safe living in the woods.

was even respected, or maybe feared is a better word, by the Shawnee Indians. On her rides Bailey often came across a particular group of Shawnee Indians. They often chased her, then on one such encounter, she had had enough. Just when she was about to be caught, she jumped off her horse and hid in a log. Strangely, the Shawnee looked everywhere for her and even stopped to rest on the log, but they could not find her. Finally, they gave up and stole her horse. She waited a while after they left, and then came out of the log. She waited until nightfall, then crept into their camp and retrieved her horse…a bold move, but nothing like the next move she made. Once she was far enough away, she started screaming and shrieking at the top of her lungs. Now waking up to that would be shocking enough, but this woman was acting totally crazy, and the Shawnee thought she was possessed and therefore could not be injured by a bullet or arrow. After that display, the Shawnee saw her often, but the kept far away from her, because they were totally afraid of her. With that assurance backing her, Mad Anne knew that she was relatively safe living in the woods.

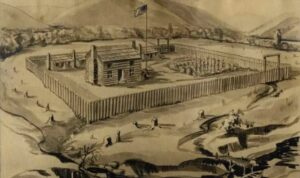

Anne met John Bailey, a member of a legendary group of frontier scouts called the Rangers, after several years living on her own. The Rangers were defending the Roanoke and Catawba settlements from Indian attacks. He was rather smitten with Mad Anne’s rough ways, and they were married November 3, 1785. In 1787, along the Kanawha River at the mouth of the Elk River, a blockhouse was built. The block house would later become Fort Lee in honor of Virginia’s Governor Henry Lee. Fort Lee was where John Bailey was assigned to duty, taking with him his now famous, gun-toting, hard-riding bride.

In 1788, John Bailey was transferred to Fort Clendenin, which was a more active area of conflict between the settlers and Native Americans. Anne Bailey began working for the settlers as well, riding on horseback to warn them of impending attacks. In 1791, she singlehandedly saved Fort Lee from certain destruction by hostile Indians with a three-day, 200–mile round trip to replenish their supply of gunpowder. She rode for hours, finally reaching Fort Savannah at Lewisburg, where the gunpowder was quickly packed aboard her horse and one additional mount, before she reversed her direction and galloped full speed back to Fort Lee.

After she returned, the siege was ended, the attackers were defeated. For her bravery Anne was given the horse that had carried her away and brought her safely back. The animal was said to have been a beautiful black, sporting white feet and a blazed face. She dubbed him Liverpool, in honor of her birthplace. Anne Bailey was forty-nine years old when she made this famous ride. Anne became a legend among the other settlers, and she was always welcome in their homes. John Bailey died in 1802, and Anne decided that she no longer wanted to live in a house, so she lived in the wilderness for over 20 years. She visited friends in town occasionally, but usually slept outside. Her favorite place was a cave near Thirteen Mile Creek.

A widow for the second time, and in her late fifties, Anne later went to live with her son, but her love for riding and of the wilderness had not ceased. For many years afterwards she could be seen riding from Point Pleasant to Lewisburg and Staunton, carrying mail and as an express messenger. Bailey continued working as a messenger,  bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. She finally retired in 1817 after making one last trip to Charleston at age 75. In 1818 Anne moved with her son and his family to his new farm in Gallia County, Ohio. Instead of asking her to stay with his family, her son, who had apparently never felt any ill-will toward his mother who was often not around, built her a cabin nearby so she would still feel independent. Bailey continued working as a messenger, bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey died at Gallipolis, Ohio, November 22, 1825, at the age of 83. She was buried in the Trotter Graveyard near her son’s home, and her remains rested there for seventy-six years. On October 10, 1901, her remains were re-interred in Monument Park in Point Pleasant, under the auspices of the Colonel Charles Lewis, Jr. Chapter of the D. A. R.

bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. She finally retired in 1817 after making one last trip to Charleston at age 75. In 1818 Anne moved with her son and his family to his new farm in Gallia County, Ohio. Instead of asking her to stay with his family, her son, who had apparently never felt any ill-will toward his mother who was often not around, built her a cabin nearby so she would still feel independent. Bailey continued working as a messenger, bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey died at Gallipolis, Ohio, November 22, 1825, at the age of 83. She was buried in the Trotter Graveyard near her son’s home, and her remains rested there for seventy-six years. On October 10, 1901, her remains were re-interred in Monument Park in Point Pleasant, under the auspices of the Colonel Charles Lewis, Jr. Chapter of the D. A. R.