History

Some people like sharing their birthday with other people, and some people don’t like that so much. I don’t know how my grandmother, Anna Spencer felt about sharing her birthday with her first child, Laura Frederick, but I suspect that she thought it was pretty cool. Of course, on the birthday that she spent laboring to give birth, I don’t suppose it was so much fun. Nevertheless, on the subsequent birthdays, it was very likely reason for celebration. I expect my Aunt Laura felt pretty much the same way. Having a “birthday buddy” or “birthday twin” as some call it, is usually considered a blessing by most people who are blessed to be such.

Some people like sharing their birthday with other people, and some people don’t like that so much. I don’t know how my grandmother, Anna Spencer felt about sharing her birthday with her first child, Laura Frederick, but I suspect that she thought it was pretty cool. Of course, on the birthday that she spent laboring to give birth, I don’t suppose it was so much fun. Nevertheless, on the subsequent birthdays, it was very likely reason for celebration. I expect my Aunt Laura felt pretty much the same way. Having a “birthday buddy” or “birthday twin” as some call it, is usually considered a blessing by most people who are blessed to be such.

Aunt Laura was an only child for the first ten years of her life, and no one has been able to tell me for sure, why  that was. I suppose Grandma just had trouble conceiving that second time. I know it happens, but ten years later, when she had my Uncle Bill Spencer, she also quickly had my dad, Al Spencer, and my aunt, Ruth Wolfe, so trouble conceiving doesn’t seem to be the likely culprit. Nevertheless, Aunt Laura had Grandma’s undivided attention for those first ten years, and the two of them were very close.

that was. I suppose Grandma just had trouble conceiving that second time. I know it happens, but ten years later, when she had my Uncle Bill Spencer, she also quickly had my dad, Al Spencer, and my aunt, Ruth Wolfe, so trouble conceiving doesn’t seem to be the likely culprit. Nevertheless, Aunt Laura had Grandma’s undivided attention for those first ten years, and the two of them were very close.

That said, I’m sure that Aunt Laura’s marriage and subsequent move to Minneapolis, Minnesota from Holyoke, Minnesota was probably a sad blow to Grandma’s heart. It’s not that the two places were so far apart in miles, but in those days, it wasn’t always easy to just jump in the car and go for a visit. It must have felt like losing

your best friend, and since Aunt Laura was just 19 years old at the time, that also meant that Grandma was left with three children under the age of ten. Of course, Aunt Laura and Uncle Fritz came for visits when they could, and she knew how much her mother loved and missed her, but her life was in Minneapolis now, and that was all there was to it. Those visit back home must have been bittersweet for both of them, but I’m sure they cherished each one. Today is the 111th anniversary of Aunt Laura’s birth. Happy birthday in Heaven, Aunt Laura. We love and miss you very much.

your best friend, and since Aunt Laura was just 19 years old at the time, that also meant that Grandma was left with three children under the age of ten. Of course, Aunt Laura and Uncle Fritz came for visits when they could, and she knew how much her mother loved and missed her, but her life was in Minneapolis now, and that was all there was to it. Those visit back home must have been bittersweet for both of them, but I’m sure they cherished each one. Today is the 111th anniversary of Aunt Laura’s birth. Happy birthday in Heaven, Aunt Laura. We love and miss you very much.

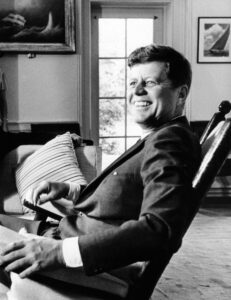

John F Kennedy, who at the time was still our future president, had to “fight” his way into war. His father believed it would make his son more “marketable” for a political run that would eventually land him in the White House. Joseph Kennedy wanted one of his sons to eventually be president, and I’m not sure he was particular about which one it was. He just knew that to have a chance, the “candidate” would have to have a military background. The reasons for his entrance into World War II really don’t matter now, because while he was in the service, he did his country proud, and even saved the lives of his PT-109 crew after a Japanese destroyer rammed them on August 2, 1943.

John F Kennedy, who at the time was still our future president, had to “fight” his way into war. His father believed it would make his son more “marketable” for a political run that would eventually land him in the White House. Joseph Kennedy wanted one of his sons to eventually be president, and I’m not sure he was particular about which one it was. He just knew that to have a chance, the “candidate” would have to have a military background. The reasons for his entrance into World War II really don’t matter now, because while he was in the service, he did his country proud, and even saved the lives of his PT-109 crew after a Japanese destroyer rammed them on August 2, 1943.

Future President Kennedy could have avoided the war completely, because he had back issues which were likely caused from a football injury. In addition, the fact that he was from a wealthy family could have been a big help in any effort he might have used to stay out of the war. He didn’t use the family’s money or influence to stay out, however. Before entering World War II, Kennedy graduated with honors from Harvard, and then still chose to serve. After being drafted to by the Navy, the physical toll on his back increased, including the physically demanding couple of days when the ship he commanded sank and he literally helped his crew survive.

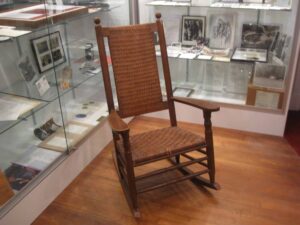

Later, while he was serving as a young senator, Kennedy’s doctor prescribed a rocking chair to be used during his service in the senate. No matter where the pain initially started or what exacerbated the issue, by the time

John F Kennedy was in the office of president, he was in constant pain. When he began using the rocking chair in 1955, Kennedy finally found a way for his muscles to relax by constantly being forced to expand and contract while sitting. The rocking chair he chose was made by P and P Chair Company, and Kennedy grew to love it. He finally found some relief, and he actually insisted that the chair be brought aboard Air Force One when he traveled. Later he just purchased many different chairs for his various residences. So impressed was Kennedy with this chair, that he also gifted dozens of the same chair to friends and colleagues. You might say that the rocking chairs from P and P Chair Company were unofficially known as the presidential rocking chairs.

John F Kennedy was in the office of president, he was in constant pain. When he began using the rocking chair in 1955, Kennedy finally found a way for his muscles to relax by constantly being forced to expand and contract while sitting. The rocking chair he chose was made by P and P Chair Company, and Kennedy grew to love it. He finally found some relief, and he actually insisted that the chair be brought aboard Air Force One when he traveled. Later he just purchased many different chairs for his various residences. So impressed was Kennedy with this chair, that he also gifted dozens of the same chair to friends and colleagues. You might say that the rocking chairs from P and P Chair Company were unofficially known as the presidential rocking chairs.

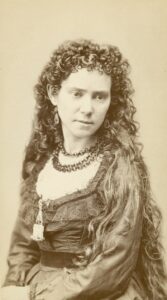

Vinnie (Lavinia) Ream was born in a log cabin in Wisconsin on September 25, 1847, like many people of her day. In a time when many women grew up to become stay-at-home moms, because they were not normally accepted in most other professions, Vinnie chose to go to college instead. She attended Christian College in Missouri, which is now known as Columbia College. One of her lesser-known accomplishments was that she played the harp to entertain her family at home, but her greatest talent and the one for which she is most well-known was in sculpture. On July 28, 1866, when Ream was just an 18-year-old girl, she became the first woman in the United States to win a commission for a statue. She was commissioned to sculpt a statue of the recently deceased President Lincoln. The statue was destined to become her most famous work, and to this day, it resides in the Rotunda of the US Capitol.

Vinnie (Lavinia) Ream was born in a log cabin in Wisconsin on September 25, 1847, like many people of her day. In a time when many women grew up to become stay-at-home moms, because they were not normally accepted in most other professions, Vinnie chose to go to college instead. She attended Christian College in Missouri, which is now known as Columbia College. One of her lesser-known accomplishments was that she played the harp to entertain her family at home, but her greatest talent and the one for which she is most well-known was in sculpture. On July 28, 1866, when Ream was just an 18-year-old girl, she became the first woman in the United States to win a commission for a statue. She was commissioned to sculpt a statue of the recently deceased President Lincoln. The statue was destined to become her most famous work, and to this day, it resides in the Rotunda of the US Capitol.

Ream didn’t start out as a sculptor, but rather began her groundbreaking career as one of the first female US government employees, working at the post office. However, when she was just 16 years old, Abraham Lincoln posed for her for 5 months during the middle of the Civil War. Perfecting the statue would take her several years to complete, including travel to Europe. She opened a studio on Broadway, but quickly moved back to Washington, DC to open a new studio there. In Washington DC, she sculpted a statue of Admiral David Farragut

in the Washington Navy Yard, and it resides appropriately at Farragut Square. Another great work of hers is the statue of Sequoyah, the Cherokee Chief that created the Cherokee alphabet. That was the first free standing statue of a Native American, and it is on display at the Statuary Hall in the US Capitol. As Ream became more and more famous, more and more opportunities opened up for her. George Custer posed for a bust, and Ream made a model of a statue of General Robert E Lee. She considered it an honor to be able to preserve so many historical figures in her sculptures.

in the Washington Navy Yard, and it resides appropriately at Farragut Square. Another great work of hers is the statue of Sequoyah, the Cherokee Chief that created the Cherokee alphabet. That was the first free standing statue of a Native American, and it is on display at the Statuary Hall in the US Capitol. As Ream became more and more famous, more and more opportunities opened up for her. George Custer posed for a bust, and Ream made a model of a statue of General Robert E Lee. She considered it an honor to be able to preserve so many historical figures in her sculptures.

Vinnie Ream died on November 20, 1914, and she is buried with honors beside her husband at Arlington National Cemetery. She was also honored with a US postage stamp and actually has a town named after her…Vinita, Oklahoma. She was also the subject of at least 3 well known portraits of herself.

During the largely unsuccessful Norwegian Campaign of World War II, the Allies were in a fight to stop the Germans from fully occupying Norway, but it didn’t work in the end. The Norwegian campaign was carried out from April 8, 1940 to June 10, 1940, and involved the attempt by Allied forces to defend northern Norway coupled with the resistance of the Norwegian military to the country’s invasion by Nazi Germany.

During the largely unsuccessful Norwegian Campaign of World War II, the Allies were in a fight to stop the Germans from fully occupying Norway, but it didn’t work in the end. The Norwegian campaign was carried out from April 8, 1940 to June 10, 1940, and involved the attempt by Allied forces to defend northern Norway coupled with the resistance of the Norwegian military to the country’s invasion by Nazi Germany.

The Norwegian Campaign was planned as Operation Wilfred and Plan R 4, prior to the actual German attack, which the Allies knew was imminent, but had not yet happened. On April 4th, the battlecruiser HMS Renown set out from Scapa Flow for the Vestfjorden with twelve destroyers. The Royal Navy and the  Kriegsmarine met at the First Battle of Narvik on April 9 – 10. The British forces conducted the Åndalsnes landings on April 13, thereby putting everything in place for the actual operation. Germany’s strategic reason for wanting Norway was to seize the port of Narvik and guarantee the delivery of iron ore needed for German steel production. In any war, steel is necessary for much of the weaponry.

Kriegsmarine met at the First Battle of Narvik on April 9 – 10. The British forces conducted the Åndalsnes landings on April 13, thereby putting everything in place for the actual operation. Germany’s strategic reason for wanting Norway was to seize the port of Narvik and guarantee the delivery of iron ore needed for German steel production. In any war, steel is necessary for much of the weaponry.

During one part of that campaign, in an air fight over Norway, a British fighter took down a German plane over a densely wooded area. Unfortunately, the British aircraft crashed as well. As it turns out, both crews survived the crashes, and while trying to get to a safe place, they encountered each other in the wilderness. In most situations, this could have been bad for one or both of the crews, but even though they were struggling against a language barrier, the rival airmen agreed not to turn on each other and instead, to team up in order to find  safety. They stayed in an abandoned hotel and shared breakfast. It wasn’t peace exactly, but they formed an uneasy truce, while they waited to see which side would show up to help first.

safety. They stayed in an abandoned hotel and shared breakfast. It wasn’t peace exactly, but they formed an uneasy truce, while they waited to see which side would show up to help first.

Instead of the British or the Germans, it was a Norwegian ski patrol that showed up to rescue the British soldiers, and of course, to take the Germans as POWs. While that one battle seemed to indicate that the British were headed for a victory over the Germans, that was not to be the case. The Germans did finally take over Norway in its entirety. Of course, as we all know, one battle is not a very good indication of who will win the war, and in the end, it was Germany that took a great fall, losing the entirety of World War II.

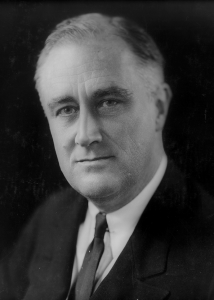

As a part of fallout of the Great Depression, and as a product of the “New Deal” ambitions of Franklin D Roosevelt, America came into the new era of Social Security, a plan to assign unique nine-digit numbers to some 26 million US workers. The plan didn’t exactly do what it was supposed to do, in a number of ways, and it has as to “social security,” it has been anything but. Social Security was not intended to be a national ID number, but it has turned out to be exactly that. It has been used by banks and insurance agencies, to track tax returns, and to identify college students. By the 1970s, Social Security numbers indexed a wealth of sensitive information in computer data banks, becoming a severe risk for identity theft, and prompting major privacy legislation. These types of security issues could not have been anticipated by the pre-computer, pre-internet, and pre-hacking America of the 1930s, when Social Security was founded.

As a part of fallout of the Great Depression, and as a product of the “New Deal” ambitions of Franklin D Roosevelt, America came into the new era of Social Security, a plan to assign unique nine-digit numbers to some 26 million US workers. The plan didn’t exactly do what it was supposed to do, in a number of ways, and it has as to “social security,” it has been anything but. Social Security was not intended to be a national ID number, but it has turned out to be exactly that. It has been used by banks and insurance agencies, to track tax returns, and to identify college students. By the 1970s, Social Security numbers indexed a wealth of sensitive information in computer data banks, becoming a severe risk for identity theft, and prompting major privacy legislation. These types of security issues could not have been anticipated by the pre-computer, pre-internet, and pre-hacking America of the 1930s, when Social Security was founded.

In November of 1936, the newly formed Social Security Board set out to assign those unique nine-digit numbers American workers. They called this a task “of a magnitude never before equaled in any Government or private undertaking.” The first Social Security number was issued on December 1, 1936, to a man named John David Sweeney Jr. Sweeney, a 23-year-old man was noted as saying that his retirement was “a long way off.” Since that time Social Security has suffered many types of abuse, and a gross miscalculation in funds, mainly stemming from the fact that with the legalizing of abortion, millions of Americans who would have eventually earned wages and paid into the program, were murdered, bringing a shortage of funds in unprecedented proportions. People will surely argue one or more of the points made here, but the facts remain.

A product of its time, the Social Security Number came about due to the economic wreckage of the Great Depression and the disastrous New Deal ambitions of Franklin D Roosevelt. People didn’t really understand the ramifications of the Social Security Numbers, because the program was overshadowed by the nation-changing program of which they were part. Nevertheless, those numbers would become affixed to nearly every American life over the next century, while spurring new uses of punch cards and filing systems, as well as all the new dilemmas around data and security. In the end, it would probably been better if we had never started it, but then I suppose that some type of national identification system was inevitable. We are a very large nation, and

in my opinion, IDs should be used for many things, such as voting, flying, re-entry to our borders, and a host of other things that make each of us unique. Maybe Social Security numbers were the only way, or maybe we could have waited on this program until we could have found a more “secure” form of Social Security.

in my opinion, IDs should be used for many things, such as voting, flying, re-entry to our borders, and a host of other things that make each of us unique. Maybe Social Security numbers were the only way, or maybe we could have waited on this program until we could have found a more “secure” form of Social Security.

I think every one of us has been the victim of a hoax. Hoaxes are like a joke…a bad joke. In reality, a hoax is a cruel scheme designed to pull one over on their intended victim. One such hoax was the story of “The Patient Bullet.” As the story goes, a man named Henry Ziegland dumped his fiancé, Maysie Tichnor, in 1883 in the town of Honey Grove, Texas. So upset was Tichnor, that she actually committed suicide. Her brother was distraught and enraged, so he decided that Ziegland had to die in retaliation. He immediately went to Ziegland’s farm and shot the young man who had hurt his sister, then so as not to face prison, he turned the gun on himself.

I think every one of us has been the victim of a hoax. Hoaxes are like a joke…a bad joke. In reality, a hoax is a cruel scheme designed to pull one over on their intended victim. One such hoax was the story of “The Patient Bullet.” As the story goes, a man named Henry Ziegland dumped his fiancé, Maysie Tichnor, in 1883 in the town of Honey Grove, Texas. So upset was Tichnor, that she actually committed suicide. Her brother was distraught and enraged, so he decided that Ziegland had to die in retaliation. He immediately went to Ziegland’s farm and shot the young man who had hurt his sister, then so as not to face prison, he turned the gun on himself.

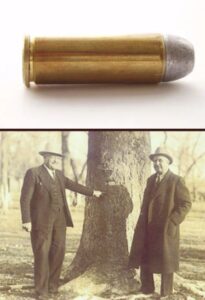

The brother died by suicide, but Ziegland did not die. In fact, somehow, he had even escaped serious injury. The bullet had only grazed him before hitting a tree. In what seemed a gross miscarriage of justice, Ziegland went on to live a prosperous life and had a family. Then, twenty years after he literally dodged a bullet, Ziegland and his son were cutting firewood. It so happened that they cut down the tree with the bullet in it. The wood in that tree was so tough that it was almost impossible to split it with an  axe. Ziegland decided to bore some holes in the fallen tree and put small amounts of dynamite in the holes. After moving about 50 feet away, Ziegland and his son set the explosions off. Shockingly, the bullet, which had waited twenty years for Henry Ziegland, was blown out of the tree with great force and the farmer was hit in the left temple and killed instantly…so the story goes anyway.

axe. Ziegland decided to bore some holes in the fallen tree and put small amounts of dynamite in the holes. After moving about 50 feet away, Ziegland and his son set the explosions off. Shockingly, the bullet, which had waited twenty years for Henry Ziegland, was blown out of the tree with great force and the farmer was hit in the left temple and killed instantly…so the story goes anyway.

Some hoaxes are pretty easy to figure out, but others, like the Ziegland story, sort of seemed plausible. Because of that, The Patient Bullet story was fairly popular. It was posted all over the Internet, complete with a picture of the bullet and the tree. The story appeared over 100 times in the newspapers, where it was presented as legitimate news. Nevertheless, there is quite a bit of evidence to suggest the story of Henry Ziegland was a hoax. In reality, there is no record of anyone with the names Ziegland or Tichnor or anything similar that ever lived in Honey Grove. In fact, a thorough search shows no vital records for people who match these dates and descriptions in Texas or any other state, for that matter.

The story was first appeared in the Jackson Mississippi Evening News in March 24, 1905. The tale was interesting, and it took off like wildfire. It was picked up by several papers, and began, “A marvelous case of punishment on earth for the sins of the flesh occurred in Dryno township, in this county, today. Twenty years ago Henry Ziegland, then a handsome, wealthy young man, jilted beautiful Maysie Tichnor, and the girl committed suicide…” After that the story disappeared for the better part of the decade, before it inexplicably  reappeared in 1913. The names were the same, but the newspapers still ran the story as current news. This time, the story’s fame grew. It ran in newspapers from Edmonton (Canada) to New Orleans to Buffalo. It’s almost a comical situation, because it was probably started by a couple of teenagers sitting around in 1905, who came up with this funny little story and decided to see if they could trick a newspaper into publishing it. Well, not only were they able to get it published, but by 1913, it was appearing in international newspapers. Now, over a century later, the story is still viewed as truth. In fact, a Google search for “Henry Ziegland bullet” produces over 5,400 results!

reappeared in 1913. The names were the same, but the newspapers still ran the story as current news. This time, the story’s fame grew. It ran in newspapers from Edmonton (Canada) to New Orleans to Buffalo. It’s almost a comical situation, because it was probably started by a couple of teenagers sitting around in 1905, who came up with this funny little story and decided to see if they could trick a newspaper into publishing it. Well, not only were they able to get it published, but by 1913, it was appearing in international newspapers. Now, over a century later, the story is still viewed as truth. In fact, a Google search for “Henry Ziegland bullet” produces over 5,400 results!

In every branch of service, and every war, the US servicemen are given a handbook. The book is filled with useful information, meant to make the transition from civilian to soldier a successful one, even if it is not an easy one. No young civilian preparing to go to war really has a good idea of what they are getting into. I suppose more of them do these days, than their World War and prior wars era counterparts. Nevertheless, each of them is proceeding head on into a massive reality check. The handbook can be a sobering little book, especially when the new soldier reads the chapter that recommends the writing of a will. The need for a Last Will and Testament will become crystal clear when the soldier sees his (or her) first battle. The sight of dead bodies takes away any misconception the soldier might have of their own mortality, and the possibility that they may have been given a one-way ticket to this battle.

In every branch of service, and every war, the US servicemen are given a handbook. The book is filled with useful information, meant to make the transition from civilian to soldier a successful one, even if it is not an easy one. No young civilian preparing to go to war really has a good idea of what they are getting into. I suppose more of them do these days, than their World War and prior wars era counterparts. Nevertheless, each of them is proceeding head on into a massive reality check. The handbook can be a sobering little book, especially when the new soldier reads the chapter that recommends the writing of a will. The need for a Last Will and Testament will become crystal clear when the soldier sees his (or her) first battle. The sight of dead bodies takes away any misconception the soldier might have of their own mortality, and the possibility that they may have been given a one-way ticket to this battle.

While many of the things contained in the handbook are sobering and even quite scary for the soldiers, there are some things contained therein that have a much more practical usage, and a few that looking back, anyway, are just a little bit funny. One such tidbit contained in the US servicemen’s World War II handbook was the simple statement that, “The British don’t know how to make a good cup of coffee. You don’t know how to make a good cup of tea—it’s an even swap.” I suppose that statement is true, at least as it pertains to the fact that British “bad coffee” is an even swap with US “bad tea.” I don’t think they US government was trying to “bad-mouth” the Brits, but rather that they were simply stating a fact. If the men were in a British camp, they simply shouldn’t ask for a cup of coffee, because they would be sorely disappointed in what they were served.

Like the warning labels of items these days, like not to shower with a running blow dryer, or to shut off the engine before trying to remove the fan belt on your car, the point was to make the reader aware of the ramifications of making such bad choices. Still, some “warnings” make more sense than others…or do they? While the electricity problem of the wet running blow dryer and the finger removal outcome of putting one’s  hand out to touch a fast-moving fan belt, seem like rather stupid wisdom (is there is such a phrase), the idea that a person would automatically make a bad cup of coffee, simply because they are British, seems equally ridiculous. Nevertheless, the US servicemen were warned to expect “bad coffee” from the British, so that they were prepared to either drink tea with the Brits, or swallow down the offending coffee so as not to offend the Brits. I’m sure that much of the rest of the handbook contained valuable information, but it is possible that the most valuable information contained in the World War II US servicemen’s handbook, was intended to avoid the notion that the Brit might have poisoned them with the British coffee.

hand out to touch a fast-moving fan belt, seem like rather stupid wisdom (is there is such a phrase), the idea that a person would automatically make a bad cup of coffee, simply because they are British, seems equally ridiculous. Nevertheless, the US servicemen were warned to expect “bad coffee” from the British, so that they were prepared to either drink tea with the Brits, or swallow down the offending coffee so as not to offend the Brits. I’m sure that much of the rest of the handbook contained valuable information, but it is possible that the most valuable information contained in the World War II US servicemen’s handbook, was intended to avoid the notion that the Brit might have poisoned them with the British coffee.

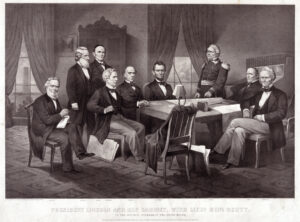

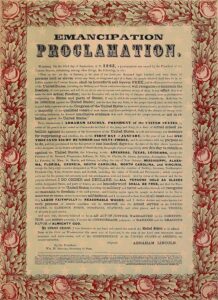

After informing his chief advisors and cabinet on July 22, 1862, that he would issue a proclamation to free enslaved people, President Abraham Lincoln added that he will wait until the Union Army has achieved a substantial military victory to make the announcement. One might wonder why the president would wait to make the announcement. It seems strange, but the reality is that he was attempting to stitch back together a nation that was being torn apart in a bloody civil war. His decision was a last-ditch, but carefully calculated, executive decision regarding the institution of slavery in America. Slavery was at the heart of the war, but at the time of the meeting with his cabinet, things were not looking good for the Union. to lose the war outright, could put an end to any possibility of freedom and of unity in this nation. The Confederate Army had overcome Union troops in significant battles, and to make matters worse, Britain and France were set to officially recognize the Confederacy as a separate nation. Lincoln was doing everything he could to see to it that that never happened.

After informing his chief advisors and cabinet on July 22, 1862, that he would issue a proclamation to free enslaved people, President Abraham Lincoln added that he will wait until the Union Army has achieved a substantial military victory to make the announcement. One might wonder why the president would wait to make the announcement. It seems strange, but the reality is that he was attempting to stitch back together a nation that was being torn apart in a bloody civil war. His decision was a last-ditch, but carefully calculated, executive decision regarding the institution of slavery in America. Slavery was at the heart of the war, but at the time of the meeting with his cabinet, things were not looking good for the Union. to lose the war outright, could put an end to any possibility of freedom and of unity in this nation. The Confederate Army had overcome Union troops in significant battles, and to make matters worse, Britain and France were set to officially recognize the Confederacy as a separate nation. Lincoln was doing everything he could to see to it that that never happened.

Lincoln’s plan was to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which strangely, had less to do with ending slavery  than saving the crumbling union. In an August 1862 letter to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, Lincoln confessed that, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and it is not either to save or to destroy slavery.” I never knew that, somehow. Lincoln was highly patriotic, and his objective was that of hoping that a strong statement declaring a national policy of emancipation would stimulate a rush of the South’s enslaved people into the ranks of the Union Army. He hoped that such a rush of manpower would resupply the Union forces, while depleting the Confederacy’s labor force, on which it depended to wage war against the North. Lincoln was against slavery, but he was for America more. That seems like a strange compromise, but I assume he thought freeing the slaves was a fight for another day. That decision would eventually get him killed.

than saving the crumbling union. In an August 1862 letter to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, Lincoln confessed that, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and it is not either to save or to destroy slavery.” I never knew that, somehow. Lincoln was highly patriotic, and his objective was that of hoping that a strong statement declaring a national policy of emancipation would stimulate a rush of the South’s enslaved people into the ranks of the Union Army. He hoped that such a rush of manpower would resupply the Union forces, while depleting the Confederacy’s labor force, on which it depended to wage war against the North. Lincoln was against slavery, but he was for America more. That seems like a strange compromise, but I assume he thought freeing the slaves was a fight for another day. That decision would eventually get him killed.

Lincoln waited to unveil the proclamation until he could do so on the heels of a successful Union military  advance, just as he had promised. After a victory at Antietam, Lincoln publicly announced a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, declaring all enslaved people free in the rebellious states as of January 1, 1863. Lincoln and his advisors limited the proclamation’s language to slavery in states outside of federal control as of 1862, which might seem odd, but if the war was lost by the Union, it wouldn’t have mattered anyway, and he needed the support of the North. Not all of the people in the north were in total agreement with the freeing of the slaves, although the vast majority were. The proclamation did not address the contentious issue of slavery within the nation’s border states. In his attempt to appease all parties, Lincoln left many loopholes open that civil rights advocates would be forced to tackle in the future. I have learned, in reference to politics, that many a politician has been forced to practice a little “appeasing” in order to get anything accomplished. I can’t say that is a good thing, but rather that it is sometimes a necessary thing.

advance, just as he had promised. After a victory at Antietam, Lincoln publicly announced a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, declaring all enslaved people free in the rebellious states as of January 1, 1863. Lincoln and his advisors limited the proclamation’s language to slavery in states outside of federal control as of 1862, which might seem odd, but if the war was lost by the Union, it wouldn’t have mattered anyway, and he needed the support of the North. Not all of the people in the north were in total agreement with the freeing of the slaves, although the vast majority were. The proclamation did not address the contentious issue of slavery within the nation’s border states. In his attempt to appease all parties, Lincoln left many loopholes open that civil rights advocates would be forced to tackle in the future. I have learned, in reference to politics, that many a politician has been forced to practice a little “appeasing” in order to get anything accomplished. I can’t say that is a good thing, but rather that it is sometimes a necessary thing.

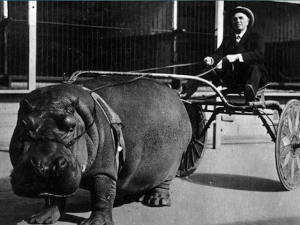

The Hippopotamus is a large, lumbering animal found mostly in Africa, or in zoos in other places. These animals are rather hot blooded and since Africa is often hot too, the like to spend much of their day almost totally immersed in water in an effort to stay cool. The hippopotamus has a bulky body with stumpy legs, an enormous head with a mouth to match, a short tail, and four toes on each foot. Each of the toes has a nail-like hoof. Male hippos are usually about 11.5 feet long, stand 5 feet tall, and weigh 3.5 tons…yes that’s tons…strange considering their relatively short stature. The males are the larger gender in terms of physical size, weighing about 30 percent more than females. The nearly hairless skin is 2 inches thick on the flanks, but thinner elsewhere. Hippos are grayish brown in color, with pinkish underparts. Their huge mouth is half a meter wide and can gape 150° to show the teeth. When the mouth is open, the head almost completely disappears. The lower teeth are very sharp and can be more than 12 inches long.

The Hippopotamus is a large, lumbering animal found mostly in Africa, or in zoos in other places. These animals are rather hot blooded and since Africa is often hot too, the like to spend much of their day almost totally immersed in water in an effort to stay cool. The hippopotamus has a bulky body with stumpy legs, an enormous head with a mouth to match, a short tail, and four toes on each foot. Each of the toes has a nail-like hoof. Male hippos are usually about 11.5 feet long, stand 5 feet tall, and weigh 3.5 tons…yes that’s tons…strange considering their relatively short stature. The males are the larger gender in terms of physical size, weighing about 30 percent more than females. The nearly hairless skin is 2 inches thick on the flanks, but thinner elsewhere. Hippos are grayish brown in color, with pinkish underparts. Their huge mouth is half a meter wide and can gape 150° to show the teeth. When the mouth is open, the head almost completely disappears. The lower teeth are very sharp and can be more than 12 inches long.

Hippopotamus is Greek for “river horse” mainly because of their love of water. So much do they love the water, that Hippos spend up to 16 hours a day submerged in rivers and lakes to keep their massive bodies cool under the hot African sun. As clumsy as they might seem on land, hippos are graceful in water, good swimmers, and can hold their breath underwater for up to five minutes. Often, in the shallow lakes, hippos are large enough to simply walk or stand on the lake floor or lie in the shallows. Because their eyes and nostrils are located high on their heads, they have the ability to see and breathe while mostly submerged. While they spend a lot of time in the water, hippos also like to enjoy the sun on the shoreline and strangely, their bodies secrete an oily red substance, which is where the myth that they sweat blood came from. The liquid is actually a skin moistener and sunblock that may also provide protection against germs. What most people wouldn’t give to have built in moisturizer and sunblock…well, maybe not a heavy sunblock. Hippos come out of the water at sunset and begin their nightly feeding cycle. Often traveling up to six miles, they consume up to 80 pounds of grass. Now, that’s a lot of carbs, but given their size, that is not that much food. Hippos seem like a slow animal, but if they are threatened on land hippos may run for the water, and they can match a human’s speed…for short distances.

In the past, hippos have been used to pull a cart, much like a horse. I suppose it was a common site in Africa,

but for most of us today, it would be a strange sight indeed. There was a hippo in the Barnes Circus, names Lotus. Lotus was an obedient cart hippo, but I’m not so sure she was very happy about that cart that was hooked on behind her. It makes sense that she would be unhappy, she was in captivity, and that she couldn’t have been happy with her life. I wonder what would happen if Lotus had been spooked near a pond. My guess is that there would have been one wet driver.

but for most of us today, it would be a strange sight indeed. There was a hippo in the Barnes Circus, names Lotus. Lotus was an obedient cart hippo, but I’m not so sure she was very happy about that cart that was hooked on behind her. It makes sense that she would be unhappy, she was in captivity, and that she couldn’t have been happy with her life. I wonder what would happen if Lotus had been spooked near a pond. My guess is that there would have been one wet driver.

Many people today think of the “V” sign as meaning Peace, but in reality, the “V” sign used today was actually hijacked. The original “V” sign meant Victory, and it was originally presented as such by Winston Spencer-Churchill at a time when Britain is at one of its lowest points in World War II. Churchill is well known as one of the greatest motivators and speech makers of his time. On July 19, 1941, he launched the “V for Victory” campaign across Europe by telling those in Europe under Nazi control to use the letter “V” (for Victory) at every chance they got in speaking and writing. Churchill urged them to write a capital letter “V” to signify “V” for Victory. This was designed to let the Germans know they still had spirit and believed they would overcome Nazi Rule. The morale of the people was so important and this low point in history. When people give up hope, wars are lost…even before the battles are lost.

Many people today think of the “V” sign as meaning Peace, but in reality, the “V” sign used today was actually hijacked. The original “V” sign meant Victory, and it was originally presented as such by Winston Spencer-Churchill at a time when Britain is at one of its lowest points in World War II. Churchill is well known as one of the greatest motivators and speech makers of his time. On July 19, 1941, he launched the “V for Victory” campaign across Europe by telling those in Europe under Nazi control to use the letter “V” (for Victory) at every chance they got in speaking and writing. Churchill urged them to write a capital letter “V” to signify “V” for Victory. This was designed to let the Germans know they still had spirit and believed they would overcome Nazi Rule. The morale of the people was so important and this low point in history. When people give up hope, wars are lost…even before the battles are lost.

In this campaign, Churchill first gave a speech over the radio to tell the people of his plan. Immediately following his speech, the letter “V” began to appear everywhere. It was painted on walls, tapped out in Morse code on shop counters with knuckles or beer glasses or pencil stubs. It quickly became a rallying call across Europe that there was still hope. Many people weren’t aware, but this is also why Churchill’s most famous pictures from World War II always featured him giving the “V” for Victory Sign. He was continuously telling the people not to give up. That all was not lost, and Victory would still be theirs. We all know the “V” sign. Of course, it was made using the index and middle fingers, raised and parted to make a “V” shape while the other fingers are clenched.

These days, it can mean a number of things, and not all are good. When it is displayed with the palm inward  toward the signer, it can be an offensive gesture in some Commonwealth nations (similar to showing the middle finger). That usage dates back to at least 1900. When it is given with the palm outward, it is to be read as a victory sign (“V for Victory”). This usage was first introduced in January 1941 as part of a campaign by the Allies of World War II and made more widely known by Churchill the following July. As most of us know, during the Vietnam War, in the 1960s, the “V sign” with palm outward was widely adopted by the counterculture as a symbol of peace. These days, that is the most commonly used meaning and is commonly called the “peace sign.” Of course, most of us also know that it is used for fun in photographs, especially in East Asia and the United States, where the gesture is also associated with cuteness…the “rabbit ears.” That one is one I have never really figured out. Not what it is, but why people think it’s so funny. Oh well…to each his own.

toward the signer, it can be an offensive gesture in some Commonwealth nations (similar to showing the middle finger). That usage dates back to at least 1900. When it is given with the palm outward, it is to be read as a victory sign (“V for Victory”). This usage was first introduced in January 1941 as part of a campaign by the Allies of World War II and made more widely known by Churchill the following July. As most of us know, during the Vietnam War, in the 1960s, the “V sign” with palm outward was widely adopted by the counterculture as a symbol of peace. These days, that is the most commonly used meaning and is commonly called the “peace sign.” Of course, most of us also know that it is used for fun in photographs, especially in East Asia and the United States, where the gesture is also associated with cuteness…the “rabbit ears.” That one is one I have never really figured out. Not what it is, but why people think it’s so funny. Oh well…to each his own.