History

When the Germans surrendered at the end of World War II, Germany was divided into four areas of control by the Allied Powers…Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. That gave those four countries governing control over their own sections of Germany, and the people in those areas. Not every country was exactly planning to do what the people might consider to be their best interests. The Allied countries had the control and the ability to dish out punishment as they saw fit. The Soviet Union considered the forced labor of Germans as part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. They wanted to exact some measure of revenge, I guess, and they were in a position to make that happen.

When the Germans surrendered at the end of World War II, Germany was divided into four areas of control by the Allied Powers…Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. That gave those four countries governing control over their own sections of Germany, and the people in those areas. Not every country was exactly planning to do what the people might consider to be their best interests. The Allied countries had the control and the ability to dish out punishment as they saw fit. The Soviet Union considered the forced labor of Germans as part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. They wanted to exact some measure of revenge, I guess, and they were in a position to make that happen.

So, the Soviet authorities deported German civilians from Germany and Eastern Europe to the USSR after World  War II as forced laborers. It almost reminds me of what happened with the Holocaust, except that the Soviet Union had no interest in killing their captives. They wanted slave labor and a measure of retaliation. Ethnic Germans living in the USSR were conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

War II as forced laborers. It almost reminds me of what happened with the Holocaust, except that the Soviet Union had no interest in killing their captives. They wanted slave labor and a measure of retaliation. Ethnic Germans living in the USSR were conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

The decision was made and the fate of the German people was sealed. In 1946, the Soviet Union forcibly relocated more than 2,500 former Nazi German specialists, including scientists, engineers, and technicians who worked in specialist areas, from companies and institutions relevant to military and economic policy in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany (SBZ) and Berlin, along with around 4,000 family members, totaling more than 6,000 people, to the Soviet Union as war reparations. These specialists with all of their knowledge and abilities, could easily change the course of history in the Soviet Union, or any country they were placed in, for that matter. Still, not all of the forced labor were specialists. Many were unskilled labor, doing menial jobs.

The good thing was that the situation in Germany after World War II was appalling. Many of the people were homeless from the bombings. I suppose that, for that reason, the forced move, while scary, was not the worst thing in the world. It was possible that a new life in the Soviet Union could be favorable when compared to war-torn Germany. It is unclear whether any Germans who were sent to the Soviet Union chose to go back to Germany, because information about forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union was suppressed in the Eastern Bloc until after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Many of those records could have also been destroyed.

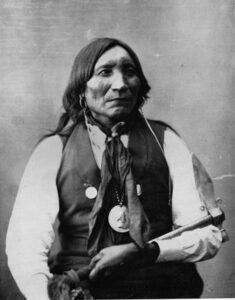

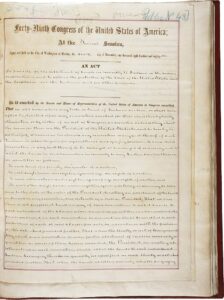

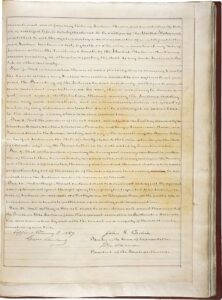

Actually, The Medicine Lodge Treaty is the name given for three treaties that were signed near Medicine Lodge, Kansas, between the Federal government of the United States and southern Plains Indian tribes on October 21, 1867. The treaties were intended to bring peace to the area by relocating the Native Americans to reservations in Indian Territory and away from European-American settlement. The Indian Peace Commission had concluded in its final report in 1868, that the wars were completely preventable. The commission determined that the United States government and its representatives, including the United States Congress, had contributed to the warfare on the Great Plains by failing to fulfill their legal obligations and to treat the Native Americans with honesty. This fact is not a new concept for anyone who has studied history at all.

Actually, The Medicine Lodge Treaty is the name given for three treaties that were signed near Medicine Lodge, Kansas, between the Federal government of the United States and southern Plains Indian tribes on October 21, 1867. The treaties were intended to bring peace to the area by relocating the Native Americans to reservations in Indian Territory and away from European-American settlement. The Indian Peace Commission had concluded in its final report in 1868, that the wars were completely preventable. The commission determined that the United States government and its representatives, including the United States Congress, had contributed to the warfare on the Great Plains by failing to fulfill their legal obligations and to treat the Native Americans with honesty. This fact is not a new concept for anyone who has studied history at all.

At the request of the tribal chiefs, the US government met the chiefs at a place traditional for Native American ceremonies. The first treaty was signed October 21, 1867, with the Kiowa and Comanche tribes. The second, with the Kiowa-Apache, was signed the same day. The third treaty was signed with the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho on October 28, 1867.

As expected, the Medicine Lodge Treaty, heavily favored the Congress and the white settlers. The tribes were assigned reservations of diminished size compared to the territories that had been defined in an 1865 treaty. The treaty tribes never actually ratified the treaty by vote of adult males…a requirement of the tribes. The Congress also changed the allotment policy under the Dawes Act and authorized sales under the Agreement with the Cheyenne and Arapaho (1890) and the Agreement with the Comanche, Kiowa and Apache (1892). With the agreement, signed with the Cherokee Commission, the Congress further reduced the reservation territory promised to the Indians. Lone Wolf, the Kiowa chief, immediately filed a lawsuit against the government for fraud on behalf of the tribes in Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock. The US Supreme Court ruled against the tribes in 1903, after determining that the Congress had “plenary power” and the political right to make such decisions. With the power of that decision to back them, Congress wasted no time in unilaterally acting in the same manner on land decisions related to other reservations as well.

Because of the outstanding issues with the treaty and subsequent government actions, in the mid-20th century, the Kiowa, Arapaho and Comanche filed several suits for claims against the US government. Over decades, they won substantial settlements of monetary compensation in the amount of tens of millions of dollars, although it

took years for the cases to be resolved.

took years for the cases to be resolved.

I don’t know what could have been done differently, exactly, other than to be completely fair with our treatment of the Indians. I have never liked the idea of forcing them to be on the reservations. The land they were given was far less than they should have received, and instead of letting them become members of society, where they could make an honest living, they were given compensation without the need to earn in, creating a group of people who could make no contribution to society at all. It basically took away their self-respect and their sense of worth…a situation which helped no one. The fighting continued until the last battle was fought on January 9, 1918.

People in our modern-day world truly take some of history’s inventions for granted. Things that have been around for a long time, are especially susceptible. Around 3000 BC, the Egyptians used early concrete forms as mortar in their construction work. The Great Pyramids at Giza were built from an early form of concrete, and they are still standing today. It seems strange to think of concrete existing way back then, but it actually did. It might not have been in exactly the same form as the concrete of today. In fact, the Bible tells of using clay and straw to make bricks and mortar. It seems rather archaic to us these days, and but then it seems to have lasted a whole lot longer than some of the concrete of today, so maybe some of it was better.

People in our modern-day world truly take some of history’s inventions for granted. Things that have been around for a long time, are especially susceptible. Around 3000 BC, the Egyptians used early concrete forms as mortar in their construction work. The Great Pyramids at Giza were built from an early form of concrete, and they are still standing today. It seems strange to think of concrete existing way back then, but it actually did. It might not have been in exactly the same form as the concrete of today. In fact, the Bible tells of using clay and straw to make bricks and mortar. It seems rather archaic to us these days, and but then it seems to have lasted a whole lot longer than some of the concrete of today, so maybe some of it was better.

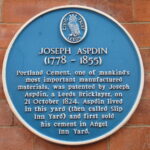

Portland cement was invented by Joseph Aspdin of England in 1824. The first concrete  paved street in the United States was laid in Bellefontaine, Ohio in 1891. The street was paved by George W Bartholomew, who owned the Buckeye Portland Cement Company and convinced city officials to let him pave an eight-foot-wide strip of Main Street with a mixture of sand, stone, and cement. Two years later, city officials agreed to let Bartholomew pave an entire block of Court Avenue between Main Street and Opera Street, which today remains the oldest concrete street in America, and it still exists, unlike some of the products currently used for streets today.

paved street in the United States was laid in Bellefontaine, Ohio in 1891. The street was paved by George W Bartholomew, who owned the Buckeye Portland Cement Company and convinced city officials to let him pave an eight-foot-wide strip of Main Street with a mixture of sand, stone, and cement. Two years later, city officials agreed to let Bartholomew pave an entire block of Court Avenue between Main Street and Opera Street, which today remains the oldest concrete street in America, and it still exists, unlike some of the products currently used for streets today.

Steel-reinforced concrete was developed by the end of the 19th century. August Perret designed and built an apartment building in Paris using steel-reinforced concrete in 1902. The building was widely admired, and with that building came a new popularity for concrete. In fact, the building influenced further development of reinforced concrete. Eugène Freyssinet really pioneered reinforced-concrete construction by building two colossal parabolic-arched airship hangars at Orly Airport in Paris in 1921.

Concrete has undergone several changes since 1921. During the 21st century, concrete manufacturers have  sstarted changing many of their product formulas in ways that increase early strength and lessen later age trength. This threw me a little bit, but the primary reason for this shift is said to be practical…”On a construction site, you can remove the forms from new concrete much faster if it has high early strength 1. Additionally, according to AZoBuild.com, concrete has gone through numerous changes over the last few decades despite its appearance looking almost the same. These changes include the development of environmentally friendly concrete products.” I’m not sure these changes are all that good, because they seem to cause more cracking and an earlier breakdown of the concrete. I’m not a contractor, but that doesn’t seem like a good thing to me.

sstarted changing many of their product formulas in ways that increase early strength and lessen later age trength. This threw me a little bit, but the primary reason for this shift is said to be practical…”On a construction site, you can remove the forms from new concrete much faster if it has high early strength 1. Additionally, according to AZoBuild.com, concrete has gone through numerous changes over the last few decades despite its appearance looking almost the same. These changes include the development of environmentally friendly concrete products.” I’m not sure these changes are all that good, because they seem to cause more cracking and an earlier breakdown of the concrete. I’m not a contractor, but that doesn’t seem like a good thing to me.

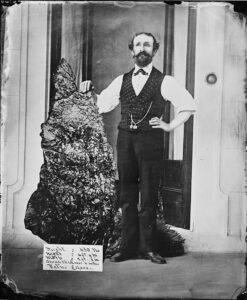

Bernhardt Otto Holtermann, who was born on April 29, 1838, was a prospector who owned part of an Australian claim where rich veins of gold were discovered after years of dry digging. I suppose it does take perseverance to successfully mine for gold, but when you consider that Holtermann finally discovered gold afteryears of digging, I would say that mining for gold also takes faith. Holtermann was born in Germany, and at adulthood set sail for Sydney, Australia in order to avoid military service. Most of his mining years were unsuccessful, including the year he even blew himself up with a premature explosion of blasting powder. Of course, his accidental explosion did not kill him, and must not have been very strong, because at the time of his greatest find, he still had all his limbs.

Bernhardt Otto Holtermann, who was born on April 29, 1838, was a prospector who owned part of an Australian claim where rich veins of gold were discovered after years of dry digging. I suppose it does take perseverance to successfully mine for gold, but when you consider that Holtermann finally discovered gold afteryears of digging, I would say that mining for gold also takes faith. Holtermann was born in Germany, and at adulthood set sail for Sydney, Australia in order to avoid military service. Most of his mining years were unsuccessful, including the year he even blew himself up with a premature explosion of blasting powder. Of course, his accidental explosion did not kill him, and must not have been very strong, because at the time of his greatest find, he still had all his limbs.

Holtermann’s “claim to fame” gold nugget was the largest gold specimen ever found, 59 inches long, weighing 630 pounds, and with an estimated gold content of 3,000 troy ounces. It was found at Hill End, near Bathurst, New South Wales. The nugget brought him enough wealth to build a mansion in North Sydney. Today, the mansion is one of the boarding houses at Sydney Church of England Grammar School (known as the Shore school). While working with one of his partners and later brother-in-law, Ludwig Hugo ‘Louis’ Beyers in their Star of Hope Gold Mining Company, in which he and Beyers were among the partners, they struck it rich. On February 22, 1868, Holtermann married Harriett Emmett, while Beyers married her sister Mary. On October 19, 1872, the Holtermann Nugget was discovered. While it was not “strictly speaking” a nugget, it was a gold specimen, a mass of gold embedded in rock, in this case quartz. Holtermann attempted to buy the 3,000-troy-ounce specimen from the company, offering £1000 over its estimated value of £12,000 (about AU$1.9 million in 2016 currency, AU$4.8 million on the 2017 gold price),  but was turned down, and the nugget was sent away to have the gold extracted. Holtermann was so upset about that, that resigned from the company in February 1873.

but was turned down, and the nugget was sent away to have the gold extracted. Holtermann was so upset about that, that resigned from the company in February 1873.

Holtermann did manage to get a photograph of himself with the nugget. This famous photo of Holtermann next to a giant “nugget” was taken by an unknown photographer. After leaving the Star of Hope Gold Mining Company, Holtermann was elected as a member for Saint Leonard’s parliament in 1882. Tragically, at the young age of just 47 years, Holtermann died in Sydney, Australia on his birthday, April 29, 1885, of “cancer of the stomach, cirrhosis of the liver, and dropsy.” He left behind his wife, three sons, and two daughters.

Bent Faurschou Hviid, who was born January 7, 1921, later became a member of the Danish resistance group Holger Danske during World War II. Because of his red hair, Hviid was nicknamed “Flammen,” which means “The Flame.” In 1951, he and his Resistance partner Jørgen Haagen Schmith, were posthumously awarded the United States Medal of Freedom by President Harry Truman. The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. The award is not limited to US citizens and, while it is a civilian award, it can also be awarded to military personnel and worn on the uniform.

Bent Faurschou Hviid, who was born January 7, 1921, later became a member of the Danish resistance group Holger Danske during World War II. Because of his red hair, Hviid was nicknamed “Flammen,” which means “The Flame.” In 1951, he and his Resistance partner Jørgen Haagen Schmith, were posthumously awarded the United States Medal of Freedom by President Harry Truman. The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. The award is not limited to US citizens and, while it is a civilian award, it can also be awarded to military personnel and worn on the uniform.

If you were to ask the men who were a part of the Holger Danske, they would tell you that no other resistance member was as hated or sought after by the Germans as was Hviid. Leader of the Holger Danske from 1943 through 1945, Gunnar Dyrberg said in the 2003 Danish documentary film, “With a Right to Kill,” that no one knows exactly how many executions “The Flame” performed, but he was rumored to have killed 22 persons. In all, it is said that the Holger Danske carried out an estimated 400 executions…performed by the Resistance agents, but apparently no one man executed more than Hviid.

Hviid grew up during World War I and was 20 when the Germans occupied Denmark. He was not about to just sit back and let the Nazis take over his country…at least, not without a fight. He entered the Holger Danske resistance group in Copenhagen. He was assigned to kill Danish Nazi officials and collaborators…traitors, who in Hviid’s opinion, did not deserve to live.

“Flammen” often partnered with “Citronen” whose real name was Jørgen Haagen Schmith. “Citronen” means “the lemon.” Schmith got this nickname because he sabotaged a Citroën garage, destroying six German cars and a tank. Citronen usually drove for Flammen, who executed their given targets. The two men were the most famous resistance duo in Denmark during World War II. While they often worked together, the Germans put the highest bounty on Flammen’s head that they offered for any Resistance fighter, due to the Faurschou of Germans who were executed by Flammen.

On October 18, 1944, while Hviid was having dinner with his landlady and some other guests, someone knocked at the door. When the door was opened, a German officer demanded entry. Hviid, who was unarmed  that evening, quickly went upstairs seeking to escape across the roof. When he reached the roof, he saw that the house was surrounded. Refusing to be taken alive, Hviid chewed a cyanide capsule and was dead a few seconds later.

that evening, quickly went upstairs seeking to escape across the roof. When he reached the roof, he saw that the house was surrounded. Refusing to be taken alive, Hviid chewed a cyanide capsule and was dead a few seconds later.

The witnesses later told of how they could hear the German soldiers upstairs cheering at the sight of the corpse. For the Germans, the form of death that took “The Flammen” out made no difference to the German soldiers. All that mattered was that he was dead. The soldiers dragged Hviid downstairs feet first, repeatedly causing his head to bang against the stairs as they went. I suppose it was a show of disrespect or perhaps, triumph for them, although they did not cause his death really.

Sometimes, you come across someone so bold and so outrageous in their actions, that you are left in complete shock. Now, I can’t say that I am the one in complete shock, but I suspect that a squad of German soldiers might have been, when on October 17, 1906, Wilhelm Voigt, a 57-year-old German shoemaker, decided to impersonate an army officer and lead an entire squad of soldiers to help him steal 4,000 marks. When calculated to American dollars and to 2023, that would be approximately $33,000. While Voigt was a shoemaker by trade, he also had a long criminal record as a thief. So, he carefully planned the robbery, knowing that the German soldiers had a long history of blind obedience.

Sometimes, you come across someone so bold and so outrageous in their actions, that you are left in complete shock. Now, I can’t say that I am the one in complete shock, but I suspect that a squad of German soldiers might have been, when on October 17, 1906, Wilhelm Voigt, a 57-year-old German shoemaker, decided to impersonate an army officer and lead an entire squad of soldiers to help him steal 4,000 marks. When calculated to American dollars and to 2023, that would be approximately $33,000. While Voigt was a shoemaker by trade, he also had a long criminal record as a thief. So, he carefully planned the robbery, knowing that the German soldiers had a long history of blind obedience.

Voigt got his hands on a captain’s uniform and hatched a plan to manipulate the German army into following his lead, thereby exploiting their blind obedience to authority and making them assist in his crazy robbery scheme. Voigt approached a troop of soldiers in Tegel, Germany. Just outside Berlin, he boldly ordered the unit to follow him 20 miles into the town of Kopenik. The group had lunch, and then Voigt put the men in position and stormed into the mayor’s office. They proceeded to arrest the mayor. He demanded to see the cash box and

confiscated the 4,000 marks inside. The mayor was put in a car, and Voigt ordered that he be delivered to the police in Berlin. Just like that, the mayor was under arrest…by an imposter.

confiscated the 4,000 marks inside. The mayor was put in a car, and Voigt ordered that he be delivered to the police in Berlin. Just like that, the mayor was under arrest…by an imposter.

And the misfit squad of soldiers proceeded to Berlin, Voigt managed to disappear with the money. No one noticed that he had gone, and it took more than a few hours at the police station before everyone realized that it was all a hoax. As for the Kaiser…well, he thought the story was funny, but They had been humiliated by the man who was obviously impersonating a captain. They launched a massive campaign to find Voigt. They wanted revenge for the fact that they were fooled. Voigt was caught in Berlin a few days later. Voigt was found guilty and was sentenced to four years for the robbery. Somehow, the Kaiser himself pulled some strings to get him out in less than two. While he was a convicted criminal after that, the people considered him a bit of a hero for the rest of his life. He even posed for pictures for years. His little ruse, while considered a crime by the Germans, made Voigt famous.

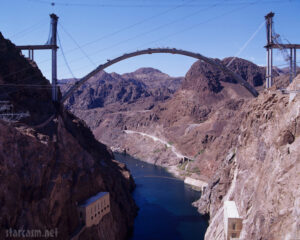

The Hoover Dam was built completed in 1935 and was considered was the greatest concrete project ever recorded, using more masonry than the Great Pyramid at Giza (4.5 million cubic yards) and equal to the amount needed to build a two-lane highway from Seattle to Miami, or a 4-foot-wide sidewalk around the Equator. It is the highest dam in the Western Hemisphere. The dam stands 726 feet above the Colorado River. It measures 1,244 feet across at the top, 660 feet thick at the base, and 45 feet thick at the top. It weighs a whopping 6.6 million tons, or at least the sum of its parts weighs that.

The Hoover Dam was built completed in 1935 and was considered was the greatest concrete project ever recorded, using more masonry than the Great Pyramid at Giza (4.5 million cubic yards) and equal to the amount needed to build a two-lane highway from Seattle to Miami, or a 4-foot-wide sidewalk around the Equator. It is the highest dam in the Western Hemisphere. The dam stands 726 feet above the Colorado River. It measures 1,244 feet across at the top, 660 feet thick at the base, and 45 feet thick at the top. It weighs a whopping 6.6 million tons, or at least the sum of its parts weighs that.

The Mike O’Callaghan–Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge came along 75 years later. It is an arch bridge that spans the Colorado River between the states of Arizona and Nevada. Located in  the Lake Mead National Recreation Area approximately 30 miles southeast of Las Vegas, it was designed to reroute US 93 from its previous routing along the top of Hoover Dam and removed several hairpin turns and blind curves from the route. The new bridge, which opened in 2010, carries Interstate 11 and US Route 93 over the Colorado River. It was the most important part of the Hoover Dam Bypass project. It is jointly named for Mike O’Callaghan, Governor of Nevada from 1971 to 1979, and Pat Tillman, an American football player who left his career with the Arizona Cardinals to enlist in the United States Army and was killed in Afghanistan in 2004 by friendly fire.

the Lake Mead National Recreation Area approximately 30 miles southeast of Las Vegas, it was designed to reroute US 93 from its previous routing along the top of Hoover Dam and removed several hairpin turns and blind curves from the route. The new bridge, which opened in 2010, carries Interstate 11 and US Route 93 over the Colorado River. It was the most important part of the Hoover Dam Bypass project. It is jointly named for Mike O’Callaghan, Governor of Nevada from 1971 to 1979, and Pat Tillman, an American football player who left his career with the Arizona Cardinals to enlist in the United States Army and was killed in Afghanistan in 2004 by friendly fire.

While the original design of the Hoover Dam seemed like a great idea, it was shown to be dangerous as early as the 1960s. The dam was also inadequate for projected traffic volumes. Work  on a different design began in 1998, and in March of 2001, the Federal Highway Administration selected the route, which crosses the Colorado River approximately 1,500 feet downstream of Hoover Dam. The construction of the bridge approaches began in 2003, and construction of the bridge itself began in February 2005. The bridge was completed in 2010 and the entire bypass route on October 16, 2010…opening to vehicle traffic on October 19, 2010. The Hoover Dam Bypass project was completed within budget at a cost of $240 million; the bridge portion cost $114 million. The bridge was also strategically placed to help prevent a terrorist attack, because it kept visitors away from the dam itself.

on a different design began in 1998, and in March of 2001, the Federal Highway Administration selected the route, which crosses the Colorado River approximately 1,500 feet downstream of Hoover Dam. The construction of the bridge approaches began in 2003, and construction of the bridge itself began in February 2005. The bridge was completed in 2010 and the entire bypass route on October 16, 2010…opening to vehicle traffic on October 19, 2010. The Hoover Dam Bypass project was completed within budget at a cost of $240 million; the bridge portion cost $114 million. The bridge was also strategically placed to help prevent a terrorist attack, because it kept visitors away from the dam itself.

In every army, navy, and air force, there are exceptional soldiers…even among the enemy. During World War II, the German Luftwaffe had an incredible pilot. His name was Erich Rudorffer, and he is credited with shooting down thirteen Soviet aircraft in a single mission on October 11, 1943. In that historic mission while flying an FW-190, Rudorffer downed eight Yak-7s and five Yak-9s of the Soviet Air Force. He eventually shot down 222 enemy aircraft and ended up his combat career flying the Messerschmitt ME-262, the first operational jet fighter.

In every army, navy, and air force, there are exceptional soldiers…even among the enemy. During World War II, the German Luftwaffe had an incredible pilot. His name was Erich Rudorffer, and he is credited with shooting down thirteen Soviet aircraft in a single mission on October 11, 1943. In that historic mission while flying an FW-190, Rudorffer downed eight Yak-7s and five Yak-9s of the Soviet Air Force. He eventually shot down 222 enemy aircraft and ended up his combat career flying the Messerschmitt ME-262, the first operational jet fighter.

Still, it wasn’t just the number of planes he shot down that made him remarkable. It was also the fact that he managed to survive the war despite flying over 1000 missions and being shot down an incredible 16 times. He was even forced to parachute from his stricken fighter planes 9 of those times. Not just a Soviet killer, Rudorffer also shot down 86 aircraft operated by Western Allied air forces. He became a commercial pilot after World War II.

Rudorffer was born on November 1, 1917, in Zwochau, which was a part of the Kingdom of Saxony of the German Empire at that time. Strangely, or maybe not, very little is said or known about his parents. That was typical of the German leadership of that era. They felt like the state, and not the parents should raise the children, because…well, parents had no training in such things. Not that the German leadership did either, but they decided that they knew more than the parents, so they pulled the children from their parents’ homes and put them in boarding schools to “train” them in the German ways. After his graduation from school, Rudorffer received a vocational education as an automobile metalsmith specialized in coachbuilding, which was likely another of the German or “Nazi” way of deciding the course of the lives of the children. He might have stayed a mechanic were it not for World War I. “Rudorffer joined the military service of the Luftwaffe with Flieger-Ersatz-Abteilung 61 (Flier Replacement Unit 61) in Oschatz on April 16, 1936. From September 2 to October 15, 1936, he served with Kampfgeschwader 253 (KG 253—253rd Bomber Wing) and from October16, 1936 to February 24, 1937, he was trained as an aircraft engine mechanic at the Technische Schule Adlershof, the technical school at Adlershof in Berlin. On March 14, 1937, Rudorffer was posted to Kampfgeschwader 153 (KG 153—153rd Bomber Wing), where he served as a mechanic until end October 1938. After that, he was transferred to Flieger-Ersatz-Abteilung 51 (Flier Replacement Unit 51) based at Liegnitz in Silesia, present-day Legnica in Poland, for flight training. Rudorffer was first trained as a bomber pilot and then as a Zerstörer, a heavy fighter or destroyer, pilot. In the winter of 1944 Rudorffer was trained on the ME 262 jet fighter. In February 1945, he was recalled to command I. Gruppe JG 7 “Nowotny” from Major Theodor Weissenberger who replaced Steinhoff as Geschwaderkommodore. Rudorffer claimed 12 victories with the ME 262, to bring his total to 222. His tally  included 136 on the Eastern Front, 26 in North Africa, and 60 on the Western Front including 10 heavy bombers.”

included 136 on the Eastern Front, 26 in North Africa, and 60 on the Western Front including 10 heavy bombers.”

After the war ended, Rudorffer started out flying DC-2s and DC-3s in Australia. Later, he worked for Pan Am and the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt, Germany’s civil aviation authority. Rudorffer was honored as one of the characters in the 2007 Finnish war movie “Tali-Ihantala 1944.” A FW 190 participated, painted in the same markings as Rudorffer’s aircraft in 1944. The aircraft, now based at Omaka Aerodrome in New Zealand, still wears the colors of Rudorffer’s machine. Rudorffer died in April 2016 at the age of 98. At the time of his death, he was the last living recipient of the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords.

The RMS Leinster was an Irish ship, which served as the Kingstown-Holyhead mailboat and was operated by the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company. In 1895, the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company ordered four steamers for Royal Mail service, named for four provinces of Ireland. The ships were RMS Leinster, RMS Connaught, RMS Munster, and RMS Ulster. The Leinster was a 3,069-ton packet steamship with a service speed of 23 knots. The ship was built at Laird’s in Birkenhead, England. It had two independent four-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines. She has launched September 12, 1896. In a perfect world, guns would not be needed on a mail ship. Then, during the World War I, the twin-propellered ship was armed with one 12-pounder and two signal guns. The war made this protection necessary. Even with the guns for protection, RMS Leinster, like her sister ships, was vulnerable to the ever present and dangerous German U-Boats. The ship continued her run, until she found herself in the wrong place at the wrong time. RMS Leinster was torpedoed and sunk by the German U-Boat U-123, on October 10, 1918. She sank just outside Dublin Bay at a point 4 nautical miles east of the Kish light.

The RMS Leinster was an Irish ship, which served as the Kingstown-Holyhead mailboat and was operated by the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company. In 1895, the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company ordered four steamers for Royal Mail service, named for four provinces of Ireland. The ships were RMS Leinster, RMS Connaught, RMS Munster, and RMS Ulster. The Leinster was a 3,069-ton packet steamship with a service speed of 23 knots. The ship was built at Laird’s in Birkenhead, England. It had two independent four-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines. She has launched September 12, 1896. In a perfect world, guns would not be needed on a mail ship. Then, during the World War I, the twin-propellered ship was armed with one 12-pounder and two signal guns. The war made this protection necessary. Even with the guns for protection, RMS Leinster, like her sister ships, was vulnerable to the ever present and dangerous German U-Boats. The ship continued her run, until she found herself in the wrong place at the wrong time. RMS Leinster was torpedoed and sunk by the German U-Boat U-123, on October 10, 1918. She sank just outside Dublin Bay at a point 4 nautical miles east of the Kish light.

The ship had, in addition to its crew, a number of civilian mail workers. The exact number of dead is unknown, but researchers from the National Maritime Museum believe it was at least 564. The ship’s log, however, states that she carried 77 crew and 694 passengers on her final voyage. This number would seem more correct to me simply because of the records normally kept in logbooks. There is someone assigned to keep that log, and while they could have done a poor job, it is more unlikely that just trusting the number to a random guess of a historian who came along later. The sinking wasn’t the first attack that had been waged on RMS Leister. She had been previously attacked in the Irish Sea, but the torpedoes missed their target. On October 10, 1918, the manifest included more than 100 British civilians, 22 postal sorters (working in the mail room) and almost 500  military personnel from the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force. Also aboard were nurses from Great Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.

military personnel from the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force. Also aboard were nurses from Great Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.

Just before 10am, as RMS Leister was sailing east of the Kish Bank in a heavy swell, some of the passengers saw a torpedo approach from the port side and pass in front of the bow. I’m sure a panic ensued, and then a second torpedo followed shortly afterwards. This torpedo struck the ship forward on the port side in the vicinity of the mail room. The ship attempted evasive action, trying to make a U-turn in an attempt to return to Kingstown, but the damage was done. As it began to settle slowly by the bow, RMS Leister sank rapidly, helped along by a third torpedo strike, which caused a huge explosion. Whether the number of victims listed is right or wrong, doesn’t really matter, because either number would make the sinking of RMS Leister, the largest single loss of life in the Irish Sea.

Despite the heavy seas, the crew managed to launch several lifeboats and some passengers clung to life-rafts. The survivors were rescued by HMS Lively, HMS Mallard, and HMS Seal. Among the civilian passengers lost in the sinking were socially prominent people such as Lady Phyllis Hamilton, daughter of the Duke of Abercorn, Robert Jocelyn Alexander, son of Irish composer Cecil Frances Alexander, Reverand John Bartley, the Presbyterian minister of Tralee who was travelling to visit his mortally wounded son in hospital, Thomas Foley and his wife Charlotte Foley (née Barrett) who was the brother-in-law of the world-famous Irish tenor John McCormack who adopted their eldest son, and Richard Moore, only son of British architect Temple Moore. The first member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service to die on active duty, Josephine Carr, was among those who died, as were two prominent officials of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, James McCarron and Patrick Lynch. Several of the military personnel who died are buried in Grangegorman Military Cemetery.

On October 18, 1918, at 9:10am U-125, outbound from Germany, picked up a radio message requesting advice on the best way to get through the North Sea minefield. The sender was U-123. Extra mines had been added to the minefield since U-123 had made her outward voyage from Germany. As U-125 had just come through the minefield, U-125 radioed back with a suggested route. U-123 acknowledged the message and was never heard from again. The following say, ten days after the sinking of the RMS Leinster, U-123 detonated a mine and sank while trying to cross the North Sea and return to base in Imperial Germany. There were no survivors. In 1991, the anchor of the RMS Leinster was raised by local divers. It was placed near Carlisle Pier and officially dedicated on January 28, 1996.

On October 18, 1918, at 9:10am U-125, outbound from Germany, picked up a radio message requesting advice on the best way to get through the North Sea minefield. The sender was U-123. Extra mines had been added to the minefield since U-123 had made her outward voyage from Germany. As U-125 had just come through the minefield, U-125 radioed back with a suggested route. U-123 acknowledged the message and was never heard from again. The following say, ten days after the sinking of the RMS Leinster, U-123 detonated a mine and sank while trying to cross the North Sea and return to base in Imperial Germany. There were no survivors. In 1991, the anchor of the RMS Leinster was raised by local divers. It was placed near Carlisle Pier and officially dedicated on January 28, 1996.

It seemed like a simple matter of a choice. Juliane Margaret Beate Koepcke, who was born on October 10, 1954, was set to graduate in Lima, Peru on December 23, 1971, and she wanted to attend her graduation ceremony before flying home to Panguana with her mother, Maria Koepcke. Juliane the only child of German zoologists Maria (née von Mikulicz-Radecki; 1924–1971) Maria and Hans-Wilhelm Koepcke (1914–2000). Her parents were working at Lima’s Museum of Natural History when she was born. When Juliane was 14, the family left Lima to establish the Panguana research station in the Amazon rainforest, where she learned survival skills. Unfortunately, the educational authorities didn’t allow this type of “schooling” and she was required to return to the Deutsche Schule Lima Alexander von Humboldt to take her exams and graduate. Maria really wanted to leave on December 19th or 20th, but she finally agreed that her daughter could stay longer. So, they scheduled a flight for Christmas Eve. All the flights were booked except for one with LANSA, an airline that Juliane’s father, Hans-Wilhelm had urged his wife to avoid flying with due to its poor reputation. Disregarding the warning, Maria booked tickets on LANSA flight 508.

It seemed like a simple matter of a choice. Juliane Margaret Beate Koepcke, who was born on October 10, 1954, was set to graduate in Lima, Peru on December 23, 1971, and she wanted to attend her graduation ceremony before flying home to Panguana with her mother, Maria Koepcke. Juliane the only child of German zoologists Maria (née von Mikulicz-Radecki; 1924–1971) Maria and Hans-Wilhelm Koepcke (1914–2000). Her parents were working at Lima’s Museum of Natural History when she was born. When Juliane was 14, the family left Lima to establish the Panguana research station in the Amazon rainforest, where she learned survival skills. Unfortunately, the educational authorities didn’t allow this type of “schooling” and she was required to return to the Deutsche Schule Lima Alexander von Humboldt to take her exams and graduate. Maria really wanted to leave on December 19th or 20th, but she finally agreed that her daughter could stay longer. So, they scheduled a flight for Christmas Eve. All the flights were booked except for one with LANSA, an airline that Juliane’s father, Hans-Wilhelm had urged his wife to avoid flying with due to its poor reputation. Disregarding the warning, Maria booked tickets on LANSA flight 508.

Mid-way through the flight, the plane was struck by lightning. The plane actually began to disintegrate before plummeting to the ground. Suddenly, Juliane found herself, still strapped to her seat, falling 10,000 feet into the Amazon rainforest. Amazingly, she survived the fall, but she was injured. She suffered a broken collarbone, a deep cut on her right arm, an eye injury, and a concussion. Juliane then spent 11 days in the rainforest, most of which were spent making her way through water by following a creek to a river. Apparently, no one knew  that she was there, or that she was missing from the wreckage of the plane. The jungle is a very unforgiving place for those without some kind of protection, and Juliane found herself dealing with severe insect bites and an infestation of maggots in her wounded arm. I’m sure that she could not believe that after surviving a fall of 10,000 feet, she might die in the jungle from whatever animal or insect might attack her. Nine days into her ordeal, she came upon an encampment that had been set up by local fishermen. There, she was able to at least give herself basic first aid. It was crude, however, and included pouring gasoline on her arm to force the maggots out of the wound. Then, she waited. After a few hours, the returning fishermen found her, gave her proper first aid, and used a canoe to transport her to a more inhabited area. Finally, she was soon airlifted to a hospital.

that she was there, or that she was missing from the wreckage of the plane. The jungle is a very unforgiving place for those without some kind of protection, and Juliane found herself dealing with severe insect bites and an infestation of maggots in her wounded arm. I’m sure that she could not believe that after surviving a fall of 10,000 feet, she might die in the jungle from whatever animal or insect might attack her. Nine days into her ordeal, she came upon an encampment that had been set up by local fishermen. There, she was able to at least give herself basic first aid. It was crude, however, and included pouring gasoline on her arm to force the maggots out of the wound. Then, she waited. After a few hours, the returning fishermen found her, gave her proper first aid, and used a canoe to transport her to a more inhabited area. Finally, she was soon airlifted to a hospital.

Many experts have tried to speculate as to how Juliane could have possibly survived. Some said that she survived the fall because she was harnessed into her seat, the window seat, which was attached to the two seats to her left as part of a row of three. They thought that somehow that functioned as a sort of parachute which slowed her fall. Some thought that the impact may have also been lessened by the updraft from a thunderstorm Koepcke fell through, as well as the thick foliage at her landing site. Juliane wasn’t the only passenger to have survived the initial disaster. Approximately 14 other passengers were later discovered to have survived the initial crash, but sadly, all of those died while waiting to be rescued. After recovering from her injuries, Koepcke assisted search parties in locating the crash site and recovering the bodies of victims. Her mother’s body was discovered on January 12, 1972. Juliane says, “I had nightmares for a long time, for years, and of course the grief about my mother’s death and that of the other people came back again and again. The thought ‘why was I the only survivor?’ haunts me. It always will.”

Juliane returned to her parents’ native Germany, where she fully recovered from her physical injuries. Like her parents, she studied biology at the University of Kiel and graduated in 1980. She received a doctorate from Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and returned to Peru to conduct research in mammalogy, specializing in bats. She published her thesis, “Ecological study of a bat colony in the tropical rain forest of Peru”, in 1987. In  1989, Koepcke married Erich Diller, a German entomologist who specializes in parasitic wasps. After her father died in 2000, she took over as the director of Panguana. Today, she serves as librarian at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology in Munich. Juliane’s autobiography “Als ich vom Himmel fiel: Wie mir der Dschungel mein Leben zurückgab” (German for When I Fell from the Sky: How the Jungle Gave Me My Life Back) was released in 2011. The book won that year’s Corine Literature Prize. In 2019, the government of Peru made her a Grand Officer of the Order of Merit for Distinguished Services.

1989, Koepcke married Erich Diller, a German entomologist who specializes in parasitic wasps. After her father died in 2000, she took over as the director of Panguana. Today, she serves as librarian at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology in Munich. Juliane’s autobiography “Als ich vom Himmel fiel: Wie mir der Dschungel mein Leben zurückgab” (German for When I Fell from the Sky: How the Jungle Gave Me My Life Back) was released in 2011. The book won that year’s Corine Literature Prize. In 2019, the government of Peru made her a Grand Officer of the Order of Merit for Distinguished Services.