History

Every time there is a great event like the Olympics, the World’s Fair, or in this case, the Great Exhibition, a stunning new building or structure is built to house the event. The Crystal Palace was originally located in Hyde Park, London, England. It was a cast iron and plate glass structure, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Great Exhibition took place from May 1 to October 15, 1851, with more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet exhibition hall to display their own examples of the latest technology they had developed in the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton. It was 1,851 feet long, with an interior height of 128 feet. It was three times the size of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Some say that the name of the building came from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a “palace of very crystal.”

Every time there is a great event like the Olympics, the World’s Fair, or in this case, the Great Exhibition, a stunning new building or structure is built to house the event. The Crystal Palace was originally located in Hyde Park, London, England. It was a cast iron and plate glass structure, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Great Exhibition took place from May 1 to October 15, 1851, with more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet exhibition hall to display their own examples of the latest technology they had developed in the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton. It was 1,851 feet long, with an interior height of 128 feet. It was three times the size of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Some say that the name of the building came from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a “palace of very crystal.”

The design called for 60,000 panes of glass to adorn the building. On average, a team of 80 men could fix more than 18,000 panes of sheet glass in a week. These were manufactured by the Chance Brothers. The building was finished in 39 weeks. The Crystal Palace boasted the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building. Visitors were shocked and astonished by all the clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights. The interior of the building had full grown trees!! The full-size elm trees that had been growing in the park were simply enclosed within the central exhibition hall near the 27-foot-tall Crystal Fountain. While very nice looking, the trees caused a problem with sparrows becoming a nuisance, and of course, shooting was out of the question inside a glass building. When Queen Victoria mentioned this problem to the Duke of Wellington, he offered the solution, “Sparrowhawks, Ma’am.” Now to me, that is incredulous, because you would simply be replacing on kind of bird with another, and then there was the added problem of bird violence. I don’t think the visitors would be very thrilled about the fighting birds or dropping bodies.

Incredibly, the Palace was relocated after the Great Exhibition, to an open area of South London known as Penge Place which had been excised from Penge Common. The building was rebuilt at the top of Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill, which is an affluent suburb. The Crystal Palace stood in that location from June 1854 until a fire destroyed it in November 1936. After the fire, the suburb was renamed Crystal Palace after the landmark. In addition, a park was placed in the area and named Crystal Palace Park. It surrounds the site, and is home of the Crystal Palace National Sports Centre, which was previously a football stadium that hosted the FA Cup Final between 1895 and 1914. Crystal Palace Football Club were founded at the site and played at the Cup Final venue in their early years. The site still contains Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s Crystal Palace Dinosaurs which date back to 1854.

In the 1920s, a board of trustees was set up under the guidance of manager Sir Henry Buckland. Buckland was a fair man with a great love for the Crystal Palace, decided to restore the building. Following the restoration, the visitors returned, and the Crystal Palace started to become profitable again. Buckland and his staff also worked on improving the fountains and gardens, including the Thursday evening displays of fireworks by Brocks. Then, on the evening of November 30, 1936, Buckland was walking his dog near the Palace with his daughter Crystal. Buckland had named her after the building. Always looking at the building he loved, they noticed a red glow coming from inside. Buckland went in to investigate and found two of his employees fighting a small office fire that had started after an explosion in the women’s cloakroom. Buckland could see that this was a serious fire, so they called the Penge fire brigade. It was too late. Even with the 89 fire engines and over 400 firemen, the fire was too big and too out of control to be able to extinguish it.

The infamous Crystal Palace was destroyed. The fire was so big that its glow could be seen across eight counties. With high winds that night, the fire spread quickly, and in part because of the dry old timber flooring, and the huge quantity of flammable materials in the building it burned to the ground. Buckland said, “In a few hours we have seen the end of the Crystal Palace. Yet, it will live in the memories not only of Englishmen, but the whole world.” The fire brought one-hundred thousand spectators to Sydenham Hill that night. One of the

spectators was Winston Churchill, who said, “This is the end of an age.” Unfortunately, as was common for the era, the Crystal Palace was underinsured, and with a potential rebuild cost of at least £2 million, the building was never rebuilt. John Logie Baird, who had used the South Tower and much of the lower level of the building for mechanical television experiments. Much of his work was destroyed in the fire, and Baird suspected the fire was an act of arson to destroy his work on developing television. Nevertheless, the true cause remains unknown.

spectators was Winston Churchill, who said, “This is the end of an age.” Unfortunately, as was common for the era, the Crystal Palace was underinsured, and with a potential rebuild cost of at least £2 million, the building was never rebuilt. John Logie Baird, who had used the South Tower and much of the lower level of the building for mechanical television experiments. Much of his work was destroyed in the fire, and Baird suspected the fire was an act of arson to destroy his work on developing television. Nevertheless, the true cause remains unknown.

When Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and their family contracted the measles in 1847, little did they know that it would not be measles that would endanger their lives, but the treatment given after they got over the measles. The Whitmans were American missionaries who lived and worked in the area of what is now Walla Walla, Washington. When the measles broke out, the missionaries managed to survive the disease, most likely by using normal medical protocols, but the Cayuse Indians, who lived in the area, and weren’t known for cleanliness, did not fare so well. Of course, there is no proof that it was a lack of cleanliness that caused the deaths, nor was there proof that it did not. The main reason that the Whitman Mission was included in the ensuing massacre is that the Cayuse came to them for help, and lives were lost.

When Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and their family contracted the measles in 1847, little did they know that it would not be measles that would endanger their lives, but the treatment given after they got over the measles. The Whitmans were American missionaries who lived and worked in the area of what is now Walla Walla, Washington. When the measles broke out, the missionaries managed to survive the disease, most likely by using normal medical protocols, but the Cayuse Indians, who lived in the area, and weren’t known for cleanliness, did not fare so well. Of course, there is no proof that it was a lack of cleanliness that caused the deaths, nor was there proof that it did not. The main reason that the Whitman Mission was included in the ensuing massacre is that the Cayuse came to them for help, and lives were lost.

The Whitman massacre, which was also known as the Whitman killings and the Tragedy at Waiilatpu, mostly refers to the killing of American missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, and eleven others who were involved with the mission, on November 29, 1847. The missionaries were killed by a small group of Cayuse men who accused Whitman of poisoning 200 Cayuse in his medical care during an outbreak of measles that included the Whitman household. The massacre occurred at the Whitman Mission at the junction of the Walla Walla River and Mill Creek in what is now southeastern Washington near Walla Walla. That massacre changed everything in the history of the Pacific Northwest…at least as far as the Oregon Territory was concerned anyway. The massacre caused the United States Congress to take action declaring the territorial status of the Oregon Country, thereby establishing the Oregon Territory on August 14, 1848, to protect the white settlers.

The Cayuse justified the killings by saying that any time a “medicine man” failed to bring about healing to a patient, the medicine man was killed for giving out “bad medicine” to his patients. Basically, the “medicine man” who officiated over a terminal patient, had better plan on going with the patient, because any death was going to be his fault. Basically, the Cayuse looked at Whitman’s failure to cure the Cayuse people as a criminal inability to perform his duties as “medicine man.” Of course, their “findings” were not logical, but they weren’t  thinking logically and didn’t really care anyway. The warriors were simply acting out of grief and an expectation of revenge for what they believed was a serious injustice against their people. In the White Man’s language, the massacre is usually ascribed to “the inability of Whitman, a physician, to prevent the measles outbreak.” At least three Cayuse villages held Whitman responsible for the widespread epidemic that killed those hundreds of Cayuse people, while leaving the White settlers comparatively unscathed. Some Cayuse people even accused the settlers of poisoning the Cayuse as part of a plan to take their land. Of course, justice needed to be carried out, and in the trial of five Cayuse warriors accused of the killing, the Cayuse used for their defense that it was tribal law to kill the medicine man who gives bad medicine.

thinking logically and didn’t really care anyway. The warriors were simply acting out of grief and an expectation of revenge for what they believed was a serious injustice against their people. In the White Man’s language, the massacre is usually ascribed to “the inability of Whitman, a physician, to prevent the measles outbreak.” At least three Cayuse villages held Whitman responsible for the widespread epidemic that killed those hundreds of Cayuse people, while leaving the White settlers comparatively unscathed. Some Cayuse people even accused the settlers of poisoning the Cayuse as part of a plan to take their land. Of course, justice needed to be carried out, and in the trial of five Cayuse warriors accused of the killing, the Cayuse used for their defense that it was tribal law to kill the medicine man who gives bad medicine.

Everything blew up on November 29, 1847, when Tiloukaikt, Tomahas, Kiamsumpkin, Iaiachalakis, Endoklamin, and Klokomas, who were enraged by Joe Lewis’ talk, attacked Waiilatpu. According to Mary Ann Bridger, the young daughter of mountain man Jim Bridger, who was a lodger of the mission and eyewitness to the event, the men knocked on the Whitmans’ kitchen door and demanded medicine. Bridger went on to say that “Marcus brought the medicine and began a conversation with Tiloukaikt. While Whitman was distracted, Tomahas struck him twice in the head with a hatchet from behind and another man shot him in the neck. The Cayuse men rushed outside and attacked the white men and boys working outdoors.” Whitman’s wife, Narcissa found him fatally wounded, and while he lived for several hours after the attack, and sometimes responded to her anxious reassurances, he later died of his injuries. Catherine Sager, who had been with Narcissa in another room when the attack occurred, later wrote in her reminiscences that “Tiloukaikt chopped the doctor’s face so badly that his features could not be recognized.”

Had she stayed hidden, Narcissa might have lived through the attack, but she later went to the door to look out and was immediately shot by a Cayuse man. Then she was coaxed out of the house. She died from a volley of

gunshots immediately upon leaving the house. The rest of the people killed in the massacre were Andrew Rodgers, Jacob Hoffman, LW Saunders, Walter Marsh, John and Francis Sager, Nathan Kimball, Isaac Gilliland, James Young, Crocket Bewley, and Amos Sales. A carpenter who had been working on the house, Peter Hall managed to escape the massacre and reach Fort Walla Walla to raise the alarm and get help. After leaving Fort Walla Walla, he left to warn Fort Vancouver, but he never made it. Sone think that Hall drowned in the Columbia River, while others speculate that he was caught and killed. On man, Chief “Beardy” tried to stop the massacre, but it was too out of control. The warriors were insanely crazy with grief, and nothing was going to stop their revenge. Chief “Beardy” was found crying while riding toward the Whitman Mission.

gunshots immediately upon leaving the house. The rest of the people killed in the massacre were Andrew Rodgers, Jacob Hoffman, LW Saunders, Walter Marsh, John and Francis Sager, Nathan Kimball, Isaac Gilliland, James Young, Crocket Bewley, and Amos Sales. A carpenter who had been working on the house, Peter Hall managed to escape the massacre and reach Fort Walla Walla to raise the alarm and get help. After leaving Fort Walla Walla, he left to warn Fort Vancouver, but he never made it. Sone think that Hall drowned in the Columbia River, while others speculate that he was caught and killed. On man, Chief “Beardy” tried to stop the massacre, but it was too out of control. The warriors were insanely crazy with grief, and nothing was going to stop their revenge. Chief “Beardy” was found crying while riding toward the Whitman Mission.

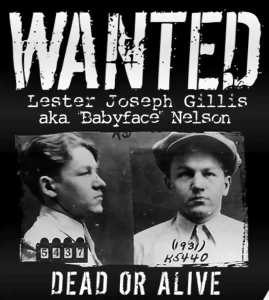

Lester Joseph Gillis may have had a baby face, but he was no innocent. The fact is that he seldom went by his real name. His alias was George Nelson and Baby Face Nelson. While he had a baby face, he was not a nice man, in fact, he was a cold-hearted killer, known for killing more FBI agents than any other criminal. Gillis was born in the Patch area of Chicago, Illinois on December 6, 1908. He was the seventh child of Belgian immigrants, Joseph and Mary Gillis. His father was a hardworking man, who worked in a tannery. Joseph strived to raise a loving family…but, somehow, with Lester, that proper upbringing didn’t work out so well. Lester’s first arrest occurred on July 4, 1921, at the age of twelve. In that incident, he accidentally shot a playmate in the jaw with a pistol that he had found. The situation was serious enough, that he served over a year in the state reformatory. When he got out at age 13, Nelson was quickly arrested again for car theft and joyriding at age 13. He was sent to a correctional school for an additional 18 months and released on April 11, 1924. Gillis’ family was horrified at his behavior, but Gillis was “on a roll” by then, and he didn’t care. He liked the “excitement” that a life of crime provided, and he wasn’t about to quit.

Lester Joseph Gillis may have had a baby face, but he was no innocent. The fact is that he seldom went by his real name. His alias was George Nelson and Baby Face Nelson. While he had a baby face, he was not a nice man, in fact, he was a cold-hearted killer, known for killing more FBI agents than any other criminal. Gillis was born in the Patch area of Chicago, Illinois on December 6, 1908. He was the seventh child of Belgian immigrants, Joseph and Mary Gillis. His father was a hardworking man, who worked in a tannery. Joseph strived to raise a loving family…but, somehow, with Lester, that proper upbringing didn’t work out so well. Lester’s first arrest occurred on July 4, 1921, at the age of twelve. In that incident, he accidentally shot a playmate in the jaw with a pistol that he had found. The situation was serious enough, that he served over a year in the state reformatory. When he got out at age 13, Nelson was quickly arrested again for car theft and joyriding at age 13. He was sent to a correctional school for an additional 18 months and released on April 11, 1924. Gillis’ family was horrified at his behavior, but Gillis was “on a roll” by then, and he didn’t care. He liked the “excitement” that a life of crime provided, and he wasn’t about to quit.

By the time he met his wife, Helen Wawrzyniak, Gillis (Baby Face Nelson) was working at a Standard Oil station in his neighborhood. Of course, that job wasn’t what it seemed either. The station doubled as the headquarters for a group of young tire thieves, known as “strippers” and Nelson fell into association with them. Through that association, Nelson acquainted himself with a number of local criminals. One of those criminals employed him to drive bootleg alcohol throughout the Chicago suburbs. Nelson quickly became a known member of the suburb-based Touhy Gang. All this happened by the time he was in his mid-teens. Very soon he became the Touhy Gang’s leader. In 1928, he married Helen Wawrzyniak, and they had two children, but that didn’t change his “bad boy ways” either. Within two years, Nelson and the gang were involved in organized crime, especially armed robbery. On January 6, 1930, the associates forced entry into the home of magazine executive Charles M Richter. After securing him up with adhesive tape and cutting the phone lines, they ransacked the house and made off with approximately $205,000 worth of jewelry, which would figure to approximately $3.3 million in 2021 dollars. Just two months later, they carried out a similar robbery at the bungalow of Lottie Brenner Von Buelow on Sheridan Road. This job netted approximately $50,000 worth of jewelry. After the crime, Chicago newspapers dubbed the gang, “The Tape Bandits.”

On April 21, 1930, Nelson and his gang robbed a bank for the first time. That take could hardly be considered  successful, at a mere $4,000. A month later, he and his gang netted $25,000 worth of jewelry from home invasions. On October 3, 1930, Nelson robbed the Itasca State Bank of $4,600…another disappointing take, and an even bigger problem, when a teller later identified him as one of the robbers. Three nights later, he brazenly stole the jewelry of the wife of Chicago mayor Big Bill Thompson, valued at $18,000. She also described her attacker, saying “He had a baby face. He was good looking, hardly more than a boy, had dark hair and was wearing a gray topcoat and a brown felt hat, turned down brim.” The net was beginning to close around Nelson. Then, he and his crew were linked to a botched roadhouse robbery in Summit, Illinois, on November 23, 1930.In the ensuing gunfight, three people were killed and three wounded. One might think that Nelson would lay low for a while, but three nights later, Nelson’s gang robbed a tavern on Waukegan Road, and Nelson committed his first murder, when he fatally shot stockbroker Edwin R Thompson.

successful, at a mere $4,000. A month later, he and his gang netted $25,000 worth of jewelry from home invasions. On October 3, 1930, Nelson robbed the Itasca State Bank of $4,600…another disappointing take, and an even bigger problem, when a teller later identified him as one of the robbers. Three nights later, he brazenly stole the jewelry of the wife of Chicago mayor Big Bill Thompson, valued at $18,000. She also described her attacker, saying “He had a baby face. He was good looking, hardly more than a boy, had dark hair and was wearing a gray topcoat and a brown felt hat, turned down brim.” The net was beginning to close around Nelson. Then, he and his crew were linked to a botched roadhouse robbery in Summit, Illinois, on November 23, 1930.In the ensuing gunfight, three people were killed and three wounded. One might think that Nelson would lay low for a while, but three nights later, Nelson’s gang robbed a tavern on Waukegan Road, and Nelson committed his first murder, when he fatally shot stockbroker Edwin R Thompson.

Throughout the winter of 1931, most of the “Tape Bandits” were rounded up, including Nelson. The Chicago Tribune referred to their leader as “George ‘Baby Face’ Nelson” who received a sentence of one year to life in the state penitentiary at Joliet. Refusing to be held, Nelson escaped during a prison transfer in February 1932. Through his contacts within the Touhy Gang, Nelson fled west to Reno, where he was harbored by William Graham, a known crime boss and gambler. He began using the alias “Jimmy Johnson” at this point. Nelson…now Johnson went to Sausalito, California, where he worked for bootlegger Joe Parente.

Nelson decided that it was time for him to have a gang of his own after the Grand Haven bank robbery. Nelson used his connections at the Green Lantern Tavern in Saint Paul, to recruit Homer Van Meter, Tommy Carroll, and Eddie Green. With his new gang, and with the addition of two other local thieves, Nelson robbed the First National Bank of Brainerd, Minnesota on October 23, 1933. The take on that robbery was $32,000, or approximately $670,000 in 2021 dollars. It was reported that Nelson wildly sprayed sub-machine gun bullets at bystanders to facilitate his getaway. Then, he picked up his wife, Helen and four-year-old son Ronald, and left with his crew for San Antonio, Texas. In San Antonia, he and his gang bought several weapons from a crooked gunsmith Hyman Lehman, one of which was a .38 Super Colt pistol that had been modified, so it was fully automatic. That gun was used by Nelson to kill Special Agent W Carter Baum at Little Bohemia Lodge several months later.

On December 9, 1933, a local woman tipped off San Antonio police regarding “high-powered Northern gangsters” in the area. Tommy Carroll was cornered two days later by two detectives who opened fire, killing Detective H.C. Perrin and wounding Detective Al Hartman. At that point, the gang split up with all the Nelson gang, except Nelson, leaving San Antonio. As a way to distance himself from the gang, Nelson and his wife traveled west to the San Francisco Bay Area. The prior close call didn’t slow him down, however. In San Francisco, he recruited John Paul Chase and Fatso Negri for a new wave of bank robberies the following spring. The next winter found him in Reno, where he met the vacationing, Alvin Karpis. Karpis introduced him to Midwestern bank robber Eddie Bentz. Teaming up with Bentz, Nelson returned to the Midwest the next summer.  On August 18, 1933, Nelson committed a major bank robbery in Grand Haven, Michigan. It was his first robbery in the area. The robbery was pretty much a failure…but it was a successful failure, because most of those involved made a full escape.

On August 18, 1933, Nelson committed a major bank robbery in Grand Haven, Michigan. It was his first robbery in the area. The robbery was pretty much a failure…but it was a successful failure, because most of those involved made a full escape.

Gillis Helped John Dillinger escape from prison in Crown Point, Indiana, and then became his partner. Nelson and the Touhy Gang were collectively “Public Enemy Number One” by the FBI. The alias, “Baby Face Nelson” came from Gillis being a short man with a youthful appearance. Still, in the professional realm, Gillis’ fellow criminals addressed him as “Jimmy.” On November 27, 1934, FBI agents fatally wounded and killed Baby Face Nelson in the Battle of Barrington, which was fought in a suburb of Chicago, Illinois.

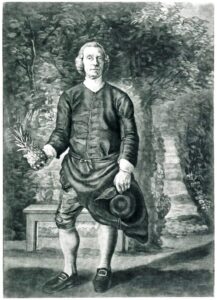

In what is one of the funniest displays of “wealth” the pineapple was once carried around as proof that the one carrying it was a first-class citizen. Now, I can’t say that I think the tradition made any sense, but in 18th century England, pineapples really were a status symbol. Their very cost set the apart as something only owned by the very rich. Like many of the upper-class citizens of that era, they liked to flaunt their wealth to those less fortunate. So, those rich enough to own a pineapple would carry them around to signify their personal wealth and high-class status. They also adorned everything from clothing to houseware with the tropical fruit.

In what is one of the funniest displays of “wealth” the pineapple was once carried around as proof that the one carrying it was a first-class citizen. Now, I can’t say that I think the tradition made any sense, but in 18th century England, pineapples really were a status symbol. Their very cost set the apart as something only owned by the very rich. Like many of the upper-class citizens of that era, they liked to flaunt their wealth to those less fortunate. So, those rich enough to own a pineapple would carry them around to signify their personal wealth and high-class status. They also adorned everything from clothing to houseware with the tropical fruit.

Pineapples were first imported from South America to Europe by Spanish explorers starting in the 16th century. Though native to South America, pineapples made their  way to the Caribbean Island of Guadeloupe. It was in Guadeloupe that Christopher Columbus first spotted their spiky crowns in 1493. He and his crew took the pineapples back to Spain, where everyone loved how sweet this new, exotic fruit tasted. Unfortunately, because they were a tropical fruit, the pineapples wouldn’t grow in Spain. The only pineapples they could get their hands on had to be imported from across the Atlantic. It was time consuming and expensive undertaking, and often resulted in rotten fruit. From Spain, they then came to England. It was in England that the pineapple became the most prestigious fruit of the 18th century. European sailors brought it home as a sign of successful expedition and evidence of their prosperity. It also became a decorative piece on upper-class dining tables. When a pineapple was seen decorating the dining table of a home, you knew that the family had traveled places and

way to the Caribbean Island of Guadeloupe. It was in Guadeloupe that Christopher Columbus first spotted their spiky crowns in 1493. He and his crew took the pineapples back to Spain, where everyone loved how sweet this new, exotic fruit tasted. Unfortunately, because they were a tropical fruit, the pineapples wouldn’t grow in Spain. The only pineapples they could get their hands on had to be imported from across the Atlantic. It was time consuming and expensive undertaking, and often resulted in rotten fruit. From Spain, they then came to England. It was in England that the pineapple became the most prestigious fruit of the 18th century. European sailors brought it home as a sign of successful expedition and evidence of their prosperity. It also became a decorative piece on upper-class dining tables. When a pineapple was seen decorating the dining table of a home, you knew that the family had traveled places and  were either explorers or merchants with money, to afford the exotic fruit.

were either explorers or merchants with money, to afford the exotic fruit.

Because of its new-found fame, the pineapple grew to be very expensive. In the American colonies in the 1700s, pineapples were no less special. They were imported from the Caribbean Islands, and the pineapples that arrived in America were very expensive. In fact, one pineapple could cost as much as $8000…in today’s dollars. While they may have been a symbol of wealth, if you ask me, carrying one around would not be a wise way to show that wealth. It wouldn’t take long for that coveted fruit to go bad, and they all you had was the memory of the money spent and thrown away.

Japan entered World War I as a member of the Allies on August 23, 1914. Assisting the Allies with the war effort was not their reason for doing so, however. Once in, Japan seized the opportunity of Imperial Germany’s distraction with the European War to expand its sphere of influence in China and the Pacific. Because Japan already had a military alliance with Britain, there was minimal fighting as they pushed through to make their territorial gains. Japan was not pressured to enter the war. The Allies had things well in hand, so their motive was obvious. As they swept through, they quickly acquired Germany’s scattered small holdings in the Pacific and on the coast of China. While those holdings were relatively easy to overtake, not all of Germany’s holdings were so easy.

Japan entered World War I as a member of the Allies on August 23, 1914. Assisting the Allies with the war effort was not their reason for doing so, however. Once in, Japan seized the opportunity of Imperial Germany’s distraction with the European War to expand its sphere of influence in China and the Pacific. Because Japan already had a military alliance with Britain, there was minimal fighting as they pushed through to make their territorial gains. Japan was not pressured to enter the war. The Allies had things well in hand, so their motive was obvious. As they swept through, they quickly acquired Germany’s scattered small holdings in the Pacific and on the coast of China. While those holdings were relatively easy to overtake, not all of Germany’s holdings were so easy.

In fact, the other Allies quickly started to realize that Japan’s motives weren’t exactly in everyone’s best interests, and they began to push back hard against Japan’s efforts to dominate China through the Twenty-One Demands of 1915. Japan’s occupation of Siberia against the Bolsheviks failed, as its wartime diplomacy and limited military action produced few results. Then, by the time of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Japan was largely frustrated in its ambitions. Nevertheless, Japan had snapped up Germany’s Asian colonies with ease, and even the African colony of Togoland (now Togo and parts of Ghana) fell in less than three weeks. The first real sign of resistance was when German Kamerun (Cameroon) was invaded and lightly contested until 1916. Still, it fell in the end. It seemed that Japan was undefeatable.

Nevertheless, with all the victories, the German colonies in East Africa led by the formidable and undefeated Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck proved to be the exception to the rule. The situation facing von Lettow-Vorbeck and his colonial forces was formidable. Still, von Lettow-Vorbeck knew how to fight, and he refused to back down. When the Japanese came up against von Lettow-Vorbeck, they found themselves heavily outnumbered, and they found themselves with no prospect of reinforcements or much in the way of material support arriving anytime soon.

The fact was that von Lettow-Vorbeck was seeking to tie up British military resources in Africa to relieve some pressure on the European theater. He drew upon his many years of service in Africa to wage a highly effective guerilla war against a much larger enemy. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was probably one of the greatest guerilla warfare strategists of all time…maybe the greatest. Von Lettow-Vorbeck even gained the loyalty of his African soldiers. In those days, it was highly unusual for a commanding officer or any white soldier for that matter, to show any level of respect to the African soldiers. Von Lettow-Vorbeck did, by appointing Black officers and speaking Swahili. The German troops had learned to live off the land and make the most of very little supplies, due to hard lessons drawn from years of colonial warfare in Africa. Those years were filled with atrocities, but they had persevered.

This one small German colonial army tied up the British forces for the duration of the conflict. The British had been plundering food  supplies that devastated the local population. Finally, the German army surrendered on November 25, 1918, in Zambia, two weeks after the November 11, 1918 armistice ended hostilities. Of course, Hitler knew a great officer when he saw one, and so after the war, Hitler immediately offered von Lettow-Vorbek a prestigious position in the Third Reich. In what most would consider a complete shock, von Lettow-Vorbeck bluntly refused the offer, using some very “colorful” language, which shall not be repeated here. It was a courageous, but not very wise move, given the circumstances. Nevertheless, his boldness, as well as his loyalty to the German people, paid off. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was simply too popular with the German people to be eliminated by the regime. He lived to be 94.

supplies that devastated the local population. Finally, the German army surrendered on November 25, 1918, in Zambia, two weeks after the November 11, 1918 armistice ended hostilities. Of course, Hitler knew a great officer when he saw one, and so after the war, Hitler immediately offered von Lettow-Vorbek a prestigious position in the Third Reich. In what most would consider a complete shock, von Lettow-Vorbeck bluntly refused the offer, using some very “colorful” language, which shall not be repeated here. It was a courageous, but not very wise move, given the circumstances. Nevertheless, his boldness, as well as his loyalty to the German people, paid off. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was simply too popular with the German people to be eliminated by the regime. He lived to be 94.

These days, we often see hot-air balloons flying over our cities in the summer. In fact, there are annual balloon festivals in many cities, and people turn out in droves to watch the colorful spectacle go up or fly over their houses. People will pay good money for a chance to take a ride in them…a chance to enjoy the freedom of floating on air for a little while and leaving all their cares far below on the ground.

These days, we often see hot-air balloons flying over our cities in the summer. In fact, there are annual balloon festivals in many cities, and people turn out in droves to watch the colorful spectacle go up or fly over their houses. People will pay good money for a chance to take a ride in them…a chance to enjoy the freedom of floating on air for a little while and leaving all their cares far below on the ground.

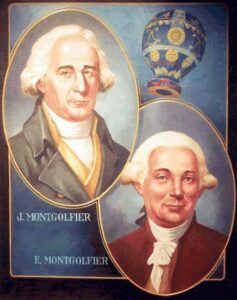

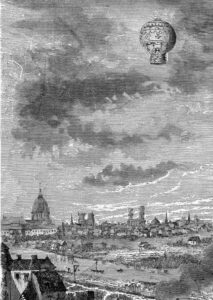

French physician Jean-François Pilatre de Rozier and François Laurent, the marquis d’ Arlandes, knew well, that desire. They made their dream of “floating on air” come true when, on November 21, 1783, they lifted of and almost silently floated over the city of Paris, France. Theirs was the first untethered hot-air balloon flight in history. They flew 5.5 miles over Paris in about 25 minutes. Their cloth balloon was crafted by French paper-making brothers Jacques-Étienne and Joseph-Michel Montgolfier, inventors of the world’s first successful hot-air balloons.

“Many inventors had tried to make a way to fly, building elaborate kins of wings and such, but nothing succeeded until the 1780s, that human flight became a reality. The first successful flying device may not have been a Montgolfier balloon but an “ornithopter,” a glider-like aircraft with flapping wings. According to a hazy record, the German architect Karl Friedrich Meerwein succeeded in lifting off the ground in an ornithopter in 1781. Whatever the veracity of this record, Meerwein’s flying machine never became a viable means of flight, and it was the Montgolfier brothers who first took men into the sky.”

The Montgolfier brothers ran a prosperous paper business in the town of Vidalon in southern France. Because they were so successful, they had the money to finance their interest in scientific experimentation. They dabbled in several areas of experimentation, and in 1782, they discovered that combustible materials burned under a lightweight paper or fabric bag would cause the bag to rise into the air. The brothers thought it was the smoke that causes balloons to rise, when actually, it is hot air that causes balloons to rise. Nevertheless, the error in the mechanics of flight didn’t hamper their further achievements.

They gave their first public demonstration on June 4, 1783, in Annonay, sending an unmanned balloon heated by burning straw and wool, 3,000 feet into the air before it settled to the ground nearly two miles away. The brothers didn’t know that the first successful hot air balloon test had preceded theirs in 1709 and was carried out by Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão, a Brazilian priest who launched a small hot-air balloon in the palace of the king of Portugal. Nevertheless, the brothers quickly outdid anything de Gusmão did.

The Montgolfiers sent a sheep, a rooster, and a duck aloft on September 19, in one of their balloons in a trial run, prior to the first manned flight. The balloon, painted azure blue and decorated with golden fleurs-de-lis, lifted up from the courtyard of the palace of Versailles in the presence of King Louis XVI. The experiment was successful, and the animals stayed afloat for eight minutes. Then, they landed safely two miles away. Finally, it  was time to try humans, so on October 15, Jean-François Pilátre de Rozier made a tethered test flight of a Montgolfier balloon. The balloon rose briefly before returning to earth. Then, finally, in a much-anticipated flight, the first untethered hot-air balloon flight occurred before a large, expectant crowd in Paris on November 21, 1783. Pilátre and d’Arlandes, an aristocrat, rose up from the grounds of royal Cháteau La Muette in the Bois de Boulogne and flew approximately five miles. Humanity had at last conquered the sky. For their achievement, the Montgolfier brothers were honored by the French Acadámie des Sciences. They went on to published books on aeronautics, and they also pursued important work in other scientific fields.

was time to try humans, so on October 15, Jean-François Pilátre de Rozier made a tethered test flight of a Montgolfier balloon. The balloon rose briefly before returning to earth. Then, finally, in a much-anticipated flight, the first untethered hot-air balloon flight occurred before a large, expectant crowd in Paris on November 21, 1783. Pilátre and d’Arlandes, an aristocrat, rose up from the grounds of royal Cháteau La Muette in the Bois de Boulogne and flew approximately five miles. Humanity had at last conquered the sky. For their achievement, the Montgolfier brothers were honored by the French Acadámie des Sciences. They went on to published books on aeronautics, and they also pursued important work in other scientific fields.

For most of us, who took gymnastics in school or other training, our school years coming to an end, usually also ends our “gymnastics career,” if it could be called that. There are some gymnasts who continue on in their career or even go on to the Olympics, but even then, most of them are finished with their gymnastics career by their late teens or early twenties. Let’s face it, gymnastics is a strenuous career, and most people just can’t take the strain very late in life or even past their very early lives. There are a few, however, who are active into their mid to late thirties, and one, Oksana Chusovitina, who is currently still active at 48 years old. Nevertheless, Chusovitina is nowhere near the oldest active gymnast.

For most of us, who took gymnastics in school or other training, our school years coming to an end, usually also ends our “gymnastics career,” if it could be called that. There are some gymnasts who continue on in their career or even go on to the Olympics, but even then, most of them are finished with their gymnastics career by their late teens or early twenties. Let’s face it, gymnastics is a strenuous career, and most people just can’t take the strain very late in life or even past their very early lives. There are a few, however, who are active into their mid to late thirties, and one, Oksana Chusovitina, who is currently still active at 48 years old. Nevertheless, Chusovitina is nowhere near the oldest active gymnast.

Johanna Quaas, who is finally “rumored” to have retired, was born November 25, 1925. She is a German gymnast who was certified by Guinness World Records April 12, 2012, as the world’s oldest active competitive gymnast. At that time, she was 86 when she broke the record. She was a regular competitor in the amateur competition Landes-Seniorenspiele (State Senior Games) in Saxony. She became known worldwide on March 26, 2012, when YouTube user LieveDaffy uploaded two videos of Quaas performing gymnastics routines…one on the parallel bars and one on the floor. Prior to that video, the tiny, 5’2″ gymnast was relatively unknown, but as the clips went viral, within six days of posting and had generated over 1.1 million views each, that all changed. In addition to being recognized by Guinness World Records, Quaas has received the Nadia Com?neci Sportsmanship Award from the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame. Being an active gymnast at 86 is unheard of, and yet, Quaas continued to compete until she suffered a torn biceps tendon in 2018, while trying to help her granddaughter. Of the incident, “She just wanted to adjust a baby chair  for her granddaughter, but the ‘nipple just wouldn’t go through the flap’ – a jerk and jerk – a severe pain in her left arm led to the above diagnosis! That hurt, of course,” said the still active senior athlete, “but strangely enough, I can now raise my arm a lot better than before, and the doctor said, let’s leave it that way for now!” Technically, she stopped performing active or competitive gymnastics. Nevertheless, in addition to fact that she can actually raise her arm better than before, she could still stand on her head at age 95. Still unable to slow down really, she has developed a bed gymnastics routine which she performs every morning and has made the routine available on YouTube and DVD published by Wissner-Bosserhoff. So, has she completely retired? Only time will tell.

for her granddaughter, but the ‘nipple just wouldn’t go through the flap’ – a jerk and jerk – a severe pain in her left arm led to the above diagnosis! That hurt, of course,” said the still active senior athlete, “but strangely enough, I can now raise my arm a lot better than before, and the doctor said, let’s leave it that way for now!” Technically, she stopped performing active or competitive gymnastics. Nevertheless, in addition to fact that she can actually raise her arm better than before, she could still stand on her head at age 95. Still unable to slow down really, she has developed a bed gymnastics routine which she performs every morning and has made the routine available on YouTube and DVD published by Wissner-Bosserhoff. So, has she completely retired? Only time will tell.

Johanna Geißler was born November 20, 1925, in Hohenmölsen, Germany. She was always an active child. She often climbed tall bars and roll on the mats. She began gymnastics at an early age and loved it immediately. She first competed at about age ten, but soon her family moved to a different part of Germany, temporarily ending her participation in competitions. When she was eleven, she began Nazi Germany’s required social  service work for girls during World War II during which she worked in farming and took care of the children of another family. After completing the compulsory social service, she trained as a gymnastics coach in Stuttgart, finishing in 1945 and moving to Weißenfels. She was still unable to work in gymnastics at that time, because it had been banned in East Germany during the first two years of post-World War II Allied occupation. So, she took up team handball instead, while in Weißenfels, learning and practicing it until the ban on gymnastics was removed in 1947. In 1950, she studied at the University of Halle to become a sports teacher. She has been an active athlete all her life, and it’s been a very long and healthy life. Today, Johanna Quaas is 98 years old. Happy birthday to this amazing lady.

service work for girls during World War II during which she worked in farming and took care of the children of another family. After completing the compulsory social service, she trained as a gymnastics coach in Stuttgart, finishing in 1945 and moving to Weißenfels. She was still unable to work in gymnastics at that time, because it had been banned in East Germany during the first two years of post-World War II Allied occupation. So, she took up team handball instead, while in Weißenfels, learning and practicing it until the ban on gymnastics was removed in 1947. In 1950, she studied at the University of Halle to become a sports teacher. She has been an active athlete all her life, and it’s been a very long and healthy life. Today, Johanna Quaas is 98 years old. Happy birthday to this amazing lady.

When Switzerland found itself in the middle of an unusual heatwave, the Gauli Glacier melted enough to uncover the wreckage debris of an American World War II plane that crash-landed in the Bernese Alps 72 years ago. Now, when you hear about the crash of a plane, especially into a mountain or in this case, a glacier, you expect to find fatalities. Of course, this plane crashed a long time ago, and the authorities already knew the outcome of that crash. The people who found the plane in the ice, however, might not have. This plane, a C-53 Skytrooper Dakota had been traveling from Austria to Italy when it collided with the Gauli Glacier at an altitude of 10,990 feet on that fateful day.

When Switzerland found itself in the middle of an unusual heatwave, the Gauli Glacier melted enough to uncover the wreckage debris of an American World War II plane that crash-landed in the Bernese Alps 72 years ago. Now, when you hear about the crash of a plane, especially into a mountain or in this case, a glacier, you expect to find fatalities. Of course, this plane crashed a long time ago, and the authorities already knew the outcome of that crash. The people who found the plane in the ice, however, might not have. This plane, a C-53 Skytrooper Dakota had been traveling from Austria to Italy when it collided with the Gauli Glacier at an altitude of 10,990 feet on that fateful day.

It was November 19, 1946, and the plane carrying four crew members and eight passengers were enjoying their trip, when something went terribly wrong. When they hit the glacier, several people were injured, amazingly, there were no fatalities. Among the passengers were high-ranking United States service members traveling with relatives…four women and one 11-year-old girl. Now, they found themselves high up on a glacier, and it was likely very cold. They were stuck at the crash site for six days before rescuers found them and could

get to them. They were forced to drink snow water and ration chocolate bars to survive, but survive they did. Many times, survival at a crash site, if you survived the initial crash, is all about using common sense and keeping your wits about you. You have to take stock of your supplies and be willing to ration what you have. You can’t let anyone get out of control, because a panic could waste vital supplies. Water is the most vital of the supplies, because while the human body can go weeks without food, it can only live a few days without water. While it would seem that water on a glacier would be plentiful, it may not be so. You would have to chip away at the ice, and then melt it to drink. In addition, you have to get it warm, or you will risk the water causing Hypothermia. This particular group managed to do things right, or at least enough right to survive the six days while they waited for rescue. Once rescued, they went on with their lives feeling very blessed to be alive.

get to them. They were forced to drink snow water and ration chocolate bars to survive, but survive they did. Many times, survival at a crash site, if you survived the initial crash, is all about using common sense and keeping your wits about you. You have to take stock of your supplies and be willing to ration what you have. You can’t let anyone get out of control, because a panic could waste vital supplies. Water is the most vital of the supplies, because while the human body can go weeks without food, it can only live a few days without water. While it would seem that water on a glacier would be plentiful, it may not be so. You would have to chip away at the ice, and then melt it to drink. In addition, you have to get it warm, or you will risk the water causing Hypothermia. This particular group managed to do things right, or at least enough right to survive the six days while they waited for rescue. Once rescued, they went on with their lives feeling very blessed to be alive.

The snow, and later, ice covered the plane as the years went by, and it was very likely forgotten…until 2012 anyway, when three young people discovered the plane’s propeller on the glacier. They continued to observe the emerging plane and as the glacier continued to melt, the scene unfolded. Today, it reportedly looks like a

field covered in plane debris, and many people probably wonder how anyone managed to live through the initial crash…much less everyone. As the glacier melted, the plane slid down the mountainside and was expected to finally emerge at the bottom. In fact, much of the debris field might actually be caused by the melting ice.

field covered in plane debris, and many people probably wonder how anyone managed to live through the initial crash…much less everyone. As the glacier melted, the plane slid down the mountainside and was expected to finally emerge at the bottom. In fact, much of the debris field might actually be caused by the melting ice.

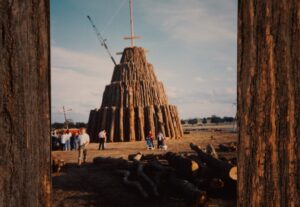

Sometimes, traditions get out of hand, and have to be called off. Such was the case with the Texas A&M University’s annual bonfire. Bonfires have long been associated with high school and college football games, usually for homecoming or the school’s main rival. The bonfire at Texas A&M was a student-built project, that became more and more elaborate every year. The bonfire being built on November 18, 1999, was probably the most elaborate and tallest bonfire structure ever. The 1999 bonfire was supposed to require more than 7,000 logs and was the labor of up to 70 workers at a time. The students had worked all night, and at approximately 2:42am, with a number of students on top of the structure, which at 59 feet high, was actually 4 feet taller than was authorized, the structure collapsed. According to Jenny Callaway, a student survivor working near the top of the stack, “It just snapped.” They had no warning. There was no audible sound, or if there was, it could not be heard over all the chatter. Dozens of students became caught in the huge log pile. Other students, such a Caleb Hill, were relatively unhurt in their 50-foot fall. At the time of the collapse, approximately 5,000 of the planned 7,000 logs were in place. Emergency medical technicians and trained first responders of the Texas A&M Emergency Care Team (TAMECT) rushed to the scene. A student-run volunteer service, who staffed each stage of construction, also began administering first aid to the victims who were thrown clear. TAMECT also alerted the University Police and University EMS, who dispatched all remaining university medics, and requested mutual aid from surrounding agencies. In addition to the mutual aid received from the College Station and Bryan, Texas EMS, Fire, and Police Departments, the members of Texas Task Force 1, the state’s elite emergency response team, were also dispatched to assist the rescue efforts.

Sometimes, traditions get out of hand, and have to be called off. Such was the case with the Texas A&M University’s annual bonfire. Bonfires have long been associated with high school and college football games, usually for homecoming or the school’s main rival. The bonfire at Texas A&M was a student-built project, that became more and more elaborate every year. The bonfire being built on November 18, 1999, was probably the most elaborate and tallest bonfire structure ever. The 1999 bonfire was supposed to require more than 7,000 logs and was the labor of up to 70 workers at a time. The students had worked all night, and at approximately 2:42am, with a number of students on top of the structure, which at 59 feet high, was actually 4 feet taller than was authorized, the structure collapsed. According to Jenny Callaway, a student survivor working near the top of the stack, “It just snapped.” They had no warning. There was no audible sound, or if there was, it could not be heard over all the chatter. Dozens of students became caught in the huge log pile. Other students, such a Caleb Hill, were relatively unhurt in their 50-foot fall. At the time of the collapse, approximately 5,000 of the planned 7,000 logs were in place. Emergency medical technicians and trained first responders of the Texas A&M Emergency Care Team (TAMECT) rushed to the scene. A student-run volunteer service, who staffed each stage of construction, also began administering first aid to the victims who were thrown clear. TAMECT also alerted the University Police and University EMS, who dispatched all remaining university medics, and requested mutual aid from surrounding agencies. In addition to the mutual aid received from the College Station and Bryan, Texas EMS, Fire, and Police Departments, the members of Texas Task Force 1, the state’s elite emergency response team, were also dispatched to assist the rescue efforts.

As with any disaster, word of the collapse spread among students and the community within minutes. By the time the sun rose, the accident was the subject of news reports around the world, and within hours, 50 news satellite trucks were broadcasting from the Texas A&M campus. Because of the precariousness of the structure, the rescue efforts took over 24 hours to complete. The process was slow, because they didn’t want to risk hurting anyone else, or further injuring the students still trapped inside. Students, including the entire Texas A&M football team and many members of the university’s Corps of Cadets, rushed to the site to assist rescue workers with the manual removal of the logs. To further complicate the rescue efforts, they had to call in the Texas A&M civil engineering department to examine the site and help the workers determine the order in which the logs could be safely removed. Also, at the request of the Texas Forest Service, Steely Lumber Company in Huntsville, Texas, sent log-moving equipment and operators to make removal safer for all concerned. At the time of the accident, there were 58 people, students and former students, working on the stack. Of those 58 people, 12 were killed and 27 were injured. Killed in the initial collapse were ten students and one former student. Another student died in the hospital the next day. The last person pulled out alive was John Comstock, who spent months in the hospital following amputation of his left leg and partial paralysis of his right side. He returned to A&M in 2001 to finish his degree.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, “the university gave the National Forestry Hero Award to an employee of Steely Lumber Company, James Gibson, for rescuing students. By 2000 Texas A&M spent over $80,000 so students and administrators could travel to the funerals of the deceased, including $40,000 so 125 students and staff could attend a funeral in Turlock, California by way of private aircraft; most of the persons on board were students. The total amount of funds spent by the university on all disaster-related expenses by that date was $292,000.” For two years, the university tried to decide on a possible way to reinstate the tradition. A task force was formed, and they proposed a new design. The task force recommended that students be allowed to participate in building the bonfire as long as they were monitored by professional construction experts. That plan wasn’t exactly received with open arms by the students. They felt like it would no longer be a student

project. In the end, it didn’t matter, because the cost of a liability policy to cover these events would cost more than $2 million per year. With that in mind, the bonfires were discontinued in 2002. Bowen’s successor Robert Gates upheld this decision. In recent years, some students have held smaller bonfires off campus, but the school is not involved with these. Multiple memorials were held to remember the victims of the disaster.

project. In the end, it didn’t matter, because the cost of a liability policy to cover these events would cost more than $2 million per year. With that in mind, the bonfires were discontinued in 2002. Bowen’s successor Robert Gates upheld this decision. In recent years, some students have held smaller bonfires off campus, but the school is not involved with these. Multiple memorials were held to remember the victims of the disaster.

Normally, when you think of something like International Students’ Day, most of us think of a day of things like walkouts, protests, and other days during which students are expected to conform to a collective norm of all these issues, like climate change, anti-war protests, and such. No matter what your stance on that is, this is not why International Students’ Day is commemorated. On November 17, 1939, in Czechoslovakia, students the University of Prague were demonstrating against the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. The Nazi occupation was protested by many groups, and yet, what was a legal protest, was turned into a mass invasion and murder of the student protesters. The event was similar to the Tiananmen Square massacre in which they opened fire on the protesters in China. That one was the Chinese government, while this one was the Nazis. I’s sure the Tiananmen Square massacre was illegal in China, but that was not the case…supposedly anyway, with the Czech protests. Today, the nations have come together in remembering the nine students who were killed, and the others who were sent to concentration camps as a result of their participation in protests over German occupation.

Normally, when you think of something like International Students’ Day, most of us think of a day of things like walkouts, protests, and other days during which students are expected to conform to a collective norm of all these issues, like climate change, anti-war protests, and such. No matter what your stance on that is, this is not why International Students’ Day is commemorated. On November 17, 1939, in Czechoslovakia, students the University of Prague were demonstrating against the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. The Nazi occupation was protested by many groups, and yet, what was a legal protest, was turned into a mass invasion and murder of the student protesters. The event was similar to the Tiananmen Square massacre in which they opened fire on the protesters in China. That one was the Chinese government, while this one was the Nazis. I’s sure the Tiananmen Square massacre was illegal in China, but that was not the case…supposedly anyway, with the Czech protests. Today, the nations have come together in remembering the nine students who were killed, and the others who were sent to concentration camps as a result of their participation in protests over German occupation.

The world was so shocked by the killings and the taking of captives, but not much could be done. Among the dead were Jan Opletal and worker Václav Sedlácek. The Nazis rounded up the students, murdered nine student leaders and sent over 1,200 students to concentration camps, mainly to Sachsenhausen. As a result of the attacks, all Czech universities and colleges were closed. Technically, by this time Czechoslovakia no longer  existed, as it had been divided into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the Slovak Republic under a fascist puppet government. The Nazi authorities were in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Their main target was students of the Medical Faculty of Charles University. That demonstration was held on October 28, and it was to commemorate the anniversary of the independence of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918. During this demonstration the student Jan Opletal was shot, and later died from his injuries on November 11th. On November 15th, his body was supposed to be transported from Prague to his home in Moravia. The funeral procession attracted thousands of students, who turned the event into an anti-Nazi demonstration. The Nazis would not allow such a demonstration, so the Nazi authorities took drastic measures in response. They closed all Czech higher education institutions, and arrested the more than 1,200 students, all of whom were then sent to concentration camps. They also executed nine students and professors without trial on November 17th. Historians speculate that the Nazis granted permission for the funeral procession already expecting a violent outcome. Their plan was to use that as a pretext for closing down universities and purging anti-fascist dissidents. I would have to agree. In that way, it was easier to place blame on the students and staff, and not the Nazis.

existed, as it had been divided into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the Slovak Republic under a fascist puppet government. The Nazi authorities were in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Their main target was students of the Medical Faculty of Charles University. That demonstration was held on October 28, and it was to commemorate the anniversary of the independence of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918. During this demonstration the student Jan Opletal was shot, and later died from his injuries on November 11th. On November 15th, his body was supposed to be transported from Prague to his home in Moravia. The funeral procession attracted thousands of students, who turned the event into an anti-Nazi demonstration. The Nazis would not allow such a demonstration, so the Nazi authorities took drastic measures in response. They closed all Czech higher education institutions, and arrested the more than 1,200 students, all of whom were then sent to concentration camps. They also executed nine students and professors without trial on November 17th. Historians speculate that the Nazis granted permission for the funeral procession already expecting a violent outcome. Their plan was to use that as a pretext for closing down universities and purging anti-fascist dissidents. I would have to agree. In that way, it was easier to place blame on the students and staff, and not the Nazis.

In 2009, on the 70th anniversary of November 17, 1939, OBESSU and ESU promoted a number of initiatives throughout Europe to commemorate the date. An event was held from the 16th to the 18th of November at the University of Brussels, focusing on the history of the students’ movement and its role in promoting active citizenship against authoritarian regimes. The conference gathered around 100 students representing national students and student unions from over 29 European countries, as well as some international delegations. Today, International Students’ Day is a day of remembrance to honor these brave students, who gave their lives and their freedom for a cause the believed in. Some countries, like Czechoslovakia have named it a national holiday.

In 2009, on the 70th anniversary of November 17, 1939, OBESSU and ESU promoted a number of initiatives throughout Europe to commemorate the date. An event was held from the 16th to the 18th of November at the University of Brussels, focusing on the history of the students’ movement and its role in promoting active citizenship against authoritarian regimes. The conference gathered around 100 students representing national students and student unions from over 29 European countries, as well as some international delegations. Today, International Students’ Day is a day of remembrance to honor these brave students, who gave their lives and their freedom for a cause the believed in. Some countries, like Czechoslovakia have named it a national holiday.