History

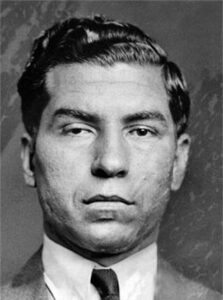

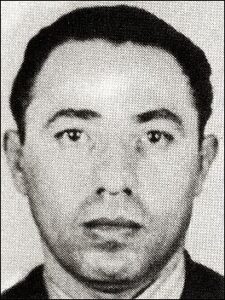

The establishment of prohibition, while originally designed to be a good thing, actually made criminals out of some people, both those who liked to have a drink and those who sold and made the alcohol. By 1931, the mob had organized. After a series of power struggles and murders, mobster Charles “Lucky” Luciano established the “Commission,” a governing body headed by five New York City crime families. Thus began four decades under the rule of the “Five Families” using tactics like loansharking, extortion, and labor union infiltration to influence and profit from a range of businesses. “They didn’t rob banks…they didn’t have to,” says Selwyn Raab, author of Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires. “They

The establishment of prohibition, while originally designed to be a good thing, actually made criminals out of some people, both those who liked to have a drink and those who sold and made the alcohol. By 1931, the mob had organized. After a series of power struggles and murders, mobster Charles “Lucky” Luciano established the “Commission,” a governing body headed by five New York City crime families. Thus began four decades under the rule of the “Five Families” using tactics like loansharking, extortion, and labor union infiltration to influence and profit from a range of businesses. “They didn’t rob banks…they didn’t have to,” says Selwyn Raab, author of Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires. “They  did all these more elegant, sophisticated crimes, because they paid more and there was less danger.” The five mob families established or basically took over a lot of different operations. They especially ran gambling and drug trafficking rings, but they also held controlling interest in construction and transportation companies.

did all these more elegant, sophisticated crimes, because they paid more and there was less danger.” The five mob families established or basically took over a lot of different operations. They especially ran gambling and drug trafficking rings, but they also held controlling interest in construction and transportation companies.

The Five Families…Genovese, Bonanno, Lucchese, Gambino and Colombo…were immigrants from Italy, particularly Sicily. Some of these were not new to the world of crime. They already had ties to Sicilian crime families, who operated according to a code of honor known as omertà…”a rule or code that prohibits speaking or divulging information about certain activities, particularly those related to criminal organizations. Omertà originated in Italy, specifically Sicily, and is often associated with the Mafia, where it represents a vow of silence regarding criminal activities and cooperation with authorities.” Because of their ties, the Five Families incorporated the concept of omertà

into the Commission. That effectively prohibited mobsters from ratting out members of their own family, as well as other families on the Commission…and it worked for a while.

into the Commission. That effectively prohibited mobsters from ratting out members of their own family, as well as other families on the Commission…and it worked for a while.

While the Five Families spent time in power, their influence diminished after the United States passed the 1970 Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO Act), which gave the government new ways to prosecute organized crime. The effectiveness of the act led mobsters to break omertà and become informants, and it even resulted in one boss flipping on his family. It is a matter of survival I guess, and apparently, while blood is thicker than water, self-preservation tops them both.

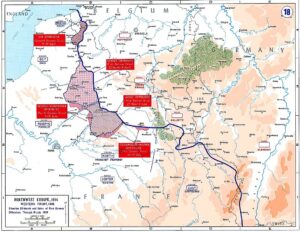

A series of German attacks along the Western Front during the First World War, beginning on March 21, 1918, known as the German Spring offensive, was also known as the Ludendorff offensive or Kaiserschlacht, which translates to Kaiser’s Battle. When the Americans entered World War I, in April 1917, the Germans knew that their days were numbered. It was decided that there was really only one way to have a chance of defeating the Allies, and that was an attack that would take place before the United States could ship soldiers across the Atlantic and fully deploy its resources. The German Army gained a temporary advantage in numbers as nearly 50 divisions had been freed by the Russian defeat and withdrawal from the war in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

A series of German attacks along the Western Front during the First World War, beginning on March 21, 1918, known as the German Spring offensive, was also known as the Ludendorff offensive or Kaiserschlacht, which translates to Kaiser’s Battle. When the Americans entered World War I, in April 1917, the Germans knew that their days were numbered. It was decided that there was really only one way to have a chance of defeating the Allies, and that was an attack that would take place before the United States could ship soldiers across the Atlantic and fully deploy its resources. The German Army gained a temporary advantage in numbers as nearly 50 divisions had been freed by the Russian defeat and withdrawal from the war in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

As parts of the German Spring offensive, there were four separate offensives. They were codenamed Michael, Georgette, Gneisenau, and Blücher-Yorck. The main attack was Michael, which was intended to break through the Allied lines, and outflank the British forces. The British forces held the front from the Somme River to the English Channel. The ultimate goal was to defeat the British Army. Once that was achieved, it was hoped that the French would seek armistice terms. The other offensives were secondary to Michael and were designed to divert Allied forces from the main offensive effort on the Somme. The Germans really had no clear objective established before the start of the offensives and once the operations were underway, the targets of the attacks were constantly changed, depending on the tactical situation. It was clearly not well planned.

Nevertheless, the Germans began advancing, and immediately struggled to maintain the momentum, mostly due to logistical issues. The fast-moving stormtrooper units could not carry enough food and ammunition to sustain themselves for long, and the army could not move in supplies and reinforcements fast enough to assist them. It left them wide open to failure. For their part, the Allies concentrated their main forces in the essential areas, such as the approaches to the Channel Ports and the rail junction of Amiens. The areas considered strategically worthless ground, which had been devastated by years of conflict, were left lightly defended. The danger of a German breakthrough passed within a few weeks, although related fighting continued until July.

While largely unsuccessful, the German Army, nevertheless made the deepest advances either side had made on the Western Front since 1914. They re-took much ground that they had lost in 1916–17 and took some ground that they had not yet controlled. I suppose that could have been considered at least a partial success, but despite these apparent successes, the Germans also suffered heavy casualties in return for land that was of little strategic value and hard to defend. In the end, the offensive failed to deliver a blow that could save Germany from defeat, meaning it came at such a significant cost to the Germans that it was basically a defeat.

In July 1918, the Allies regained their numerical advantage with the arrival of American troops and by August, they used this and improved tactics to launch a counteroffensive. The ensuing Hundred Days Offensive resulted in the Germans losing all of the ground that they had taken in the Spring Offensive, the collapse of the Hindenburg Line, and the capitulation of Germany that November. They didn’t stand a chance.

In July 1918, the Allies regained their numerical advantage with the arrival of American troops and by August, they used this and improved tactics to launch a counteroffensive. The ensuing Hundred Days Offensive resulted in the Germans losing all of the ground that they had taken in the Spring Offensive, the collapse of the Hindenburg Line, and the capitulation of Germany that November. They didn’t stand a chance.

When a dam is built, the purpose is to create a reservoir, thereby allowing for the accumulated water to be used to create irrigation for local farmers. In theory, that was the plan for the dam in Hot Springs County, Wyoming that would become known as Anchor Dam, and the resulting “reservoir” to be nicknamed “the reservoir that wouldn’t hold water” and occasionally, “boondoggle.” The dam is located 35 miles west of Thermopolis, Wyoming.

When a dam is built, the purpose is to create a reservoir, thereby allowing for the accumulated water to be used to create irrigation for local farmers. In theory, that was the plan for the dam in Hot Springs County, Wyoming that would become known as Anchor Dam, and the resulting “reservoir” to be nicknamed “the reservoir that wouldn’t hold water” and occasionally, “boondoggle.” The dam is located 35 miles west of Thermopolis, Wyoming.

The US Bureau of Reclamation built the dam in the 1950s. It was intended to provide a reliable supply of irrigation water, but after three years and $3.4 million spent on construction, it became clear that the geology of the area would not allow the reservoir to fill. After more than a decade of continuing attempts at remediation, the final cost of the dam topped $7 million, and its reservoir still holds very little water. The concrete thin-arch dam was completed in 1960 by the United States Bureau of Reclamation as a water storage project. The 208-foot-high dam structure impounds the water of the South Fork of Owl Creek, with the spillway designed as an unnecessary central overflow. Owl Creek rises in the Absaroka Mountains of northwestern Wyoming, and it was the site of early agriculture in the area. As homesteaders settled the region in the 1890s, it would become Hot Springs County. No area can support agriculture or livestock without water, so they knew something would have to be done. Ranchers used irrigation ditches to bring water from Owl Creek to pastures or to help grow livestock feed crops like alfalfa.

As construction began, the crews discovered “solution cavities” in the bedrock forced the re-positioning and re-configuration of the dam, causing delays and added expense. Solution caves or cavities are formed by the dissolution of rock along and adjacent to joints, fractures, and faults. These cavities are created by water passing through soluble rocks, leading to underground cavities and cave systems. The same karst solution cavities prevented Anchor Reservoir from filling its design capacity of 17,400 acre-feet. The reservoir has never been full. Since the dam was constructed, more than 50 sinkholes had been identified in the underlying Chugwater Formation geology of the reservoir basin. Some of the sinkholes were 30 feet in diameter and 35 feet deep. The site’s lack of “hydraulic integrity” was well known to Bureau scientists before and during construction, which begs the question…why was this project ever approved?

Bureau of Reclamation policies mandated that the Owl Creek farmers must organize an irrigation district, which would oversee distributing water to members and collecting payment. This was not well received, and a number of farmers in the area did not want to join, for two reasons. First, not everyone thought they needed the extra water, and they thought that their business would suffer if had recurring repayment costs for the project. Under Wyoming’s “first-in-time-first-in-rights” system of water law, farmers and ranchers with water rights filed earlier in time are allowed to take all the water they are entitled to before their neighbors with later rights get any. On Owl Creek, the farmers and ranchers who joined later and therefore had lower priority water rights tended to favor the proposed reservoir.

The Bureau of Reclamation rule that farmers getting project water could not own more than 160 acres, or 320 if married, was a source of contention, however. This rule was designed with the small family farm on fertile soil in mind. In the high altitude, short season, arid Owl Creek Mountains, 320 acres was nowhere near enough for cattle ranching, meaning that the rancher would not contribute. Efforts by local dam proponents to force reluctant ranchers to join the irrigation district prompted a series of lawsuits that held up progress on Anchor Dam until 1954. In 1954, Wyoming’s US senator, Frank Barrett, succeeded in having Anchor Dam exempted

from the acreage limit. Immediately, a group of ranchers changed their minds and joined the irrigation district. With that, the Bureau of Reclamation began seriously planning for construction. Nevertheless, it was all for not, because in the end, the reservoir only filled enough to provide some irrigation benefit through July and August of each season, as it still is today. The Anchor dam is still operated by the local Owl Creek Irrigation District.

from the acreage limit. Immediately, a group of ranchers changed their minds and joined the irrigation district. With that, the Bureau of Reclamation began seriously planning for construction. Nevertheless, it was all for not, because in the end, the reservoir only filled enough to provide some irrigation benefit through July and August of each season, as it still is today. The Anchor dam is still operated by the local Owl Creek Irrigation District.

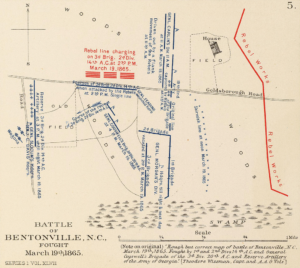

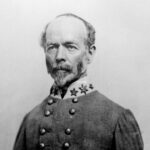

As one side of a war begins to lose the battle to the other side, the army of the losing side, really begins to weaken. While the Battle of Bentonville was not the end of the Civil War, it was on the downhill run to the end. On March 19, 1865, at the Battle of Bentonville, North Carolina, Confederate General Joseph Johnston made a desperate attempt to stop Union General William T Sherman’s drive through the Carolinas. Unfortunately for Johnston, his bedraggled force couldn’t stop the advance of Sherman’s mighty army. Sherman’s men were well supplied and strong.

As one side of a war begins to lose the battle to the other side, the army of the losing side, really begins to weaken. While the Battle of Bentonville was not the end of the Civil War, it was on the downhill run to the end. On March 19, 1865, at the Battle of Bentonville, North Carolina, Confederate General Joseph Johnston made a desperate attempt to stop Union General William T Sherman’s drive through the Carolinas. Unfortunately for Johnston, his bedraggled force couldn’t stop the advance of Sherman’s mighty army. Sherman’s men were well supplied and strong.

Sherman had taken a month off following his famous March to the Sea in late 1864. He stopped for a little rest and relaxation in Savannah, Georgia. Following his time off, Sherman turned north into the Carolinas. As he went, he literally destroyed everything in his path. It was his plan to demoralize the South and so bring the end of the war. Sherman left Savannah with 60,000 men divided into two wings, capturing Columbia and South Carolina, in February. Then he continued towards Goldsboro, North Carolina, where he planned to meet up with another army coming from the coast. His plan was to march to Petersburg, Virginia, where he would join General Ulysses S Grant and crush the army of Robert E Lee, the largest remaining Confederate force.

It was Sherman’s assumption that the Rebel forces in the Carolinas were too thinly spread to offer any much resistance, but Johnston had managed to put 17,000 soldiers together and proceeded to attack one of Sherman’s wings at Bentonville on March 19th. The attack was a surprise to the Yankees, and for a time, they were driven back. Then, a Union counterattack halted the advance and darkness halted the fighting. The next day, Johnston managed to establish a strong defensive position, where he waited and hoped for a Yankee assault. As more Union troops arrived, Sherman had a nearly three to one advantage over Johnston. When a Union force threatened to cut off the Rebel’s only line of retreat on March 21st, Johnston withdrew northward.

In the battles, the Union lost 194 men who were killed, 1,112 who were wounded, and they had 221 missing. The Confederates lost some 240 men who were killed, 1,700 who were wounded, and they had 1,500 missing. Johnston wrote to Lee concerning Sherman, that, he couldn’t do anything more than annoy him. Knowing that he had lost, just one month later, Johnston surrendered his army to Sherman.

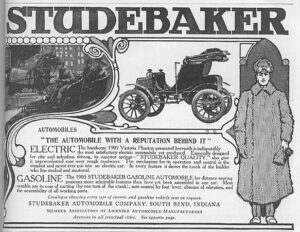

Over the years, a number of automobile makers have come and gone. Their technology likely became outdated, and the next big thing came on the scene. Such was the fate of the makers of the Studebaker on March 18, 1933. At that point, they were heavily in debt, and it seemed there was no way out. The company went into receivership. As sometimes happens, the company’s president, Albert Erskine, resigned and later that year committed suicide. The company rebounded…for a time, and perhaps if Erskine had lived, he could have brought it back to life again. In the end, Studebaker eventually rebounded from its financial troubles, but it could not sustain itself again, and so, shut down the assembly line, and abandoned the automobile business entirely in 1966.

Over the years, a number of automobile makers have come and gone. Their technology likely became outdated, and the next big thing came on the scene. Such was the fate of the makers of the Studebaker on March 18, 1933. At that point, they were heavily in debt, and it seemed there was no way out. The company went into receivership. As sometimes happens, the company’s president, Albert Erskine, resigned and later that year committed suicide. The company rebounded…for a time, and perhaps if Erskine had lived, he could have brought it back to life again. In the end, Studebaker eventually rebounded from its financial troubles, but it could not sustain itself again, and so, shut down the assembly line, and abandoned the automobile business entirely in 1966.

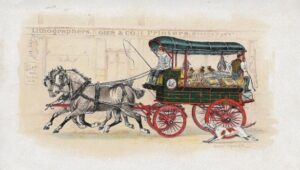

Studebaker Corporation started up in 1852, not as an automobile company, but to make wagons. Brothers Henry and Clement Studebaker opened a blacksmith shop in South Bend, Indiana that year. Their work was of good quality, and they eventually became a leading manufacturer of horse-drawn wagons, even suppling wagons to the US Army during the Civil War. As with the auto industry, the wagon industry began to fold, so Studebaker Corporation entered America’s blossoming auto industry, launching an electric car in 1902 and a gas-powered vehicle two years later that was marketed under the name Studebaker-Garford. Who knew that they could have actually been s forward thinking in 1902. Electric cars have been around longer than we might  have thought. Studebaker partnered with other automakers and began selling gas-powered cars under its own name in 1913, while continuing to make wagons until 1920, when that market dried up.

have thought. Studebaker partnered with other automakers and began selling gas-powered cars under its own name in 1913, while continuing to make wagons until 1920, when that market dried up.

Erskine was born in 1871 and took over as president of Studebaker Corporation 1915. Under his leadership, the company acquired luxury automaker Pierce-Arrow in the late 1920s and launched the affordably priced but short-lived Erskine and Rockne lines, which was named for the famous University of Notre Dame football coach, before his death in a plane crash in 1931. Rockne was paid to give talks at auto conventions and dealership events. The Great Depression hit Studebaker Corporation hard and in March 1933 it was forced into bankruptcy. Erskine was also hit hard by the Great Depression, and his great personal debt and health problems caused him to kill himself on July 1, 1933.

After Erskine’s death, the company went under new management, and they were able to get the company back on track. The Rockne brand in July 1933, and Pierce-Arrow was sold as well. In January 1935, the new Studebaker Corporation was incorporated. Raymond Loewy began working for Studebaker in the late 1930s. Loewy was a French-born industrial designer. He created iconic and popular models including the bullet-nosed 1953 Starliner and Starlight coupes and the 1963 Avanti sports coupe. It looked like the company might pull out of their funk.

Unfortunately, by the mid-1950s, Studebaker had to face the fact that they just didn’t have the resources of its Big Three competitors, so they merged with automaker Packard. Nevertheless, they continued to have financial

troubles. By the late 1950s, the Packard brand was dropped. In December 1963, Studebaker closed the South Bend plant. This ended the production of its cars and trucks in America. After the US closure, the company’s Hamilton, Ontario, facilities remained in operation until March 1966. Finally, after 114 years in business, Studebaker shut its doors for good.

troubles. By the late 1950s, the Packard brand was dropped. In December 1963, Studebaker closed the South Bend plant. This ended the production of its cars and trucks in America. After the US closure, the company’s Hamilton, Ontario, facilities remained in operation until March 1966. Finally, after 114 years in business, Studebaker shut its doors for good.

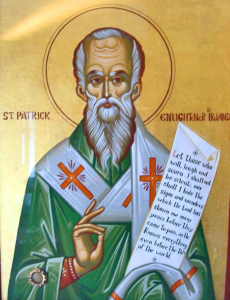

Irish blessings have a long history in Ireland. They have served as protections from harm, bringers of good luck, and personal blessings for individuals and families. The Irish blessing is deeply entwined with Ireland’s cultural and spiritual heritage, offering comfort, hope, and wisdom. As a Christian, I don’t believe in luck, but I fully understand blessings. I believe all blessings come for our Father above. My favorite Saint Patrick’s Day blessing is “May your blessings outnumber the shamrocks that grow, and may trouble avoid you wherever you go.” Being part Irish, I also love Saint Patrick’s Day, which is not just about green beer, Corned Beef and Cabbage, or pinching those who forget to wear the traditional green. Saint Patrick was a real person and the patron saint of Ireland. Taken there as a slave, he became a priest bringing Christianity to Ireland.

Irish blessings have a long history in Ireland. They have served as protections from harm, bringers of good luck, and personal blessings for individuals and families. The Irish blessing is deeply entwined with Ireland’s cultural and spiritual heritage, offering comfort, hope, and wisdom. As a Christian, I don’t believe in luck, but I fully understand blessings. I believe all blessings come for our Father above. My favorite Saint Patrick’s Day blessing is “May your blessings outnumber the shamrocks that grow, and may trouble avoid you wherever you go.” Being part Irish, I also love Saint Patrick’s Day, which is not just about green beer, Corned Beef and Cabbage, or pinching those who forget to wear the traditional green. Saint Patrick was a real person and the patron saint of Ireland. Taken there as a slave, he became a priest bringing Christianity to Ireland.

In fact, in Ireland, the day is not a party day. It’s actually a religious holiday, similar to Christmas and Easter. Things have changed some over the years, and these days you can find Saint Patrick’s Day parades, shamrocks, and green Guinness beer in Ireland, but it’s mostly there for the tourists who think that is the right way to celebrate the day. The Irish people know the truth, however. Until 1970, Irish laws mandated that the pubs be closed on Saint Patrick’s Day, making it very different from the American way of celebrating the day. It just like our oven Independence Day, which doesn’t mean the same thing to the Irish either. Every nation has its own tradition, and its own way of celebrating them. For that matter, even the different families celebrate the tradition differently. In fact, in Chicago, they actually dye the Chicago River green for the holiday, and inevitably, someone has to take a dip into the green water to celebrate the day. The river really is a cool sight in emerald green.

Some people don’t do much, besides making sure they have some green on, and some like to almost hide their green, because if someone pinches you, and you have green on (in plain sight, of course) the rule is that you get to pinch them back. In our house, when I was growing up, we loved the pinching game for not wearing green, and we might just as easily pinch someone who fooled us, by wearing the tiniest bit of green, making us prime candidates for that revenge pinch. No matter how you celebrate, here’s wishing you a blessed and happy Saint Patrick’s Day!!

Some people don’t do much, besides making sure they have some green on, and some like to almost hide their green, because if someone pinches you, and you have green on (in plain sight, of course) the rule is that you get to pinch them back. In our house, when I was growing up, we loved the pinching game for not wearing green, and we might just as easily pinch someone who fooled us, by wearing the tiniest bit of green, making us prime candidates for that revenge pinch. No matter how you celebrate, here’s wishing you a blessed and happy Saint Patrick’s Day!!

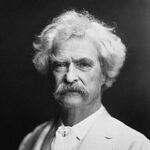

Most of us think of scammers as being a rather new thing that has developed with phone and internet technology, but it had really been around for many years. One event that had scammers all over it, was the 1910 appearance of Halley’s comet. This event was charged with superstition, panic, and yes…scammers. Qn May 6, 1910, England’s King Edward VII died, and for some reason, the death triggered a superstitious panic. This superstition caused fear over the comet’s arrival and led to panic as astronomers believed that the comet’s tail contained cyanogen, a deadly gas. Most astronomers dismissed this theory, but the damage had been done and a door opened. Many scammers started selling anti-comet pills, gas masks, and umbrellas, all of which were supposed to “protect” against this imagined threat.

Most of us think of scammers as being a rather new thing that has developed with phone and internet technology, but it had really been around for many years. One event that had scammers all over it, was the 1910 appearance of Halley’s comet. This event was charged with superstition, panic, and yes…scammers. Qn May 6, 1910, England’s King Edward VII died, and for some reason, the death triggered a superstitious panic. This superstition caused fear over the comet’s arrival and led to panic as astronomers believed that the comet’s tail contained cyanogen, a deadly gas. Most astronomers dismissed this theory, but the damage had been done and a door opened. Many scammers started selling anti-comet pills, gas masks, and umbrellas, all of which were supposed to “protect” against this imagined threat.

People really bought into the hysteria and the panic reached such a peak that people actually rushed to buy these supposed safeguards. Panic can cause people to try things they wouldn’t otherwise be foolish enough to try. Two scammers from Texas were caught selling sugar pills at as meds for an exorbitant price. The reality was that the Earth passing through the tail of a comet was an extremely unusual event, and it seems to have only happened twice. Not knowing what is in the tail of the comet, I can see how people might be nervous. After the arrest of the Texas scammers, their customers went to the extent of riots demanding their release to get their hands on these anti-comet pills. They believed the scammers over the truth. This weird historical episode shows how fear and misinformation can drive desperate measures.

In an odd coincidence, Mark Twain, who was born in 1835 when Halley’s Comet passed by Earth, famously predicted he would die upon its return. Remarkably, he passed away on April 21, 1910…just a day after the comet’s closest approach. He said, “I came in with Halley’s Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I

expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don’t go out with Halley’s Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: “Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together”. It is hard to say if he just convinced himself of it, thereby triggering the heart attack that killed him, or what. Nevertheless, his prediction came to pass.

expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don’t go out with Halley’s Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: “Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together”. It is hard to say if he just convinced himself of it, thereby triggering the heart attack that killed him, or what. Nevertheless, his prediction came to pass.

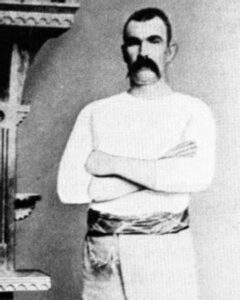

Imagine learning to swim, without water. It’s a bizarre thought, I mean, how can you learn to swim without water…seriously. Still, it can be done…in theory. In 1920, at a time when swimming pools were not readily available, the schools decided to use a little unusual ingenuity when they decided that they wanted to teach the students to swim anyway. Learning to swim without water seems like an absurd concept, but they decided that it was doable. Since many communities lacked safe, accessible bodies of water, educators improvised by teaching swimming techniques on dry land. When I saw the picture of this type of technique training, I had to laugh. They used simulated movements to help students build muscle memory and understand the basics of swimming strokes.

Imagine learning to swim, without water. It’s a bizarre thought, I mean, how can you learn to swim without water…seriously. Still, it can be done…in theory. In 1920, at a time when swimming pools were not readily available, the schools decided to use a little unusual ingenuity when they decided that they wanted to teach the students to swim anyway. Learning to swim without water seems like an absurd concept, but they decided that it was doable. Since many communities lacked safe, accessible bodies of water, educators improvised by teaching swimming techniques on dry land. When I saw the picture of this type of technique training, I had to laugh. They used simulated movements to help students build muscle memory and understand the basics of swimming strokes.

At this time, in the early 20th century, the schools were emphasizing the need for physical education. Drowning rates had become alarmingly high, so swimming was seen as both a life-saving skill and a form of exercise. Schools and community programs sought ways to introduce swimming into their curriculums, but there were problems…namely pools for classes. So, Dryland Swimming Instruction was born. It often involved students lying on benches or specially designed apparatuses, practicing arm strokes and kicking techniques. Instructors would demonstrate movements, ensuring students mimicked proper form before applying these skills in water.

While this teaching method was unconventional, it proved valuable, especially in rural areas where access to  swimming facilities was limited. Once students had the chance to practice in water, they often adapted quickly, as they had already internalized the mechanics of swimming. I would not have expected this method to be very successful, but it actually proved that creativity and determination can overcome logistical challenges. This teaching method was rather short lived, because by the mid-20th century, public swimming pools became more widespread, and so dryland swimming largely faded. Nevertheless, its legacy remains a testament to the innovative spirit of early educators striving to make swimming accessible to all. These people saw a need to make students physically fit, and safer in the water, and despite the obstacles, they came up with a way to make it happen. While it really looks rather comical, it did prove to be effective.

swimming facilities was limited. Once students had the chance to practice in water, they often adapted quickly, as they had already internalized the mechanics of swimming. I would not have expected this method to be very successful, but it actually proved that creativity and determination can overcome logistical challenges. This teaching method was rather short lived, because by the mid-20th century, public swimming pools became more widespread, and so dryland swimming largely faded. Nevertheless, its legacy remains a testament to the innovative spirit of early educators striving to make swimming accessible to all. These people saw a need to make students physically fit, and safer in the water, and despite the obstacles, they came up with a way to make it happen. While it really looks rather comical, it did prove to be effective.

When conventions are held, the main goal is to get down to business, teaching new skills, and exchanging ideas. For medical conventions, that might mean new procedures, new med inventions, or an exchange of thoughts on medical failures. It can be hard to get people to attend these things if there is nothing fun to do, so when the nation’s chiropractors descended on Chicago for a weeklong convention in May 1956, they decided to throw a beauty contest. This was not to be your average beauty contest, however. In true chiropractic style, this was to be a posture beauty pageant. I’m sure it was a novel and almost shocking thought, as beauty pageants go. Nevertheless, the women decided to compete, and the pageant was set.

When conventions are held, the main goal is to get down to business, teaching new skills, and exchanging ideas. For medical conventions, that might mean new procedures, new med inventions, or an exchange of thoughts on medical failures. It can be hard to get people to attend these things if there is nothing fun to do, so when the nation’s chiropractors descended on Chicago for a weeklong convention in May 1956, they decided to throw a beauty contest. This was not to be your average beauty contest, however. In true chiropractic style, this was to be a posture beauty pageant. I’m sure it was a novel and almost shocking thought, as beauty pageants go. Nevertheless, the women decided to compete, and the pageant was set.

Contestants were judged not only by their apparent beauty but were also judged by their X-rays and also by  their standing posture. Each girl was to stand on a pair of scales. This was a strange idea, but they stood one foot to each scale. The idea was that they should register exactly half their weight on each scale, thereby confirming the correct standing posture. I would never have thought that posture could have been measured in such a way. Nevertheless, contests like this were pretty common. The idea was to polish the reputation of the chiropractic profession which had been considered “quackish” in those days. Basically, chiropractic had a serious public relations problem. They held no medical license and so carried little weight in the medical community, according to Dr P Reginald Hug, who is a past president of the Association for the History of Chiropractic. Hugs says, “We were the new kids on the block and medicine didn’t like us.”

their standing posture. Each girl was to stand on a pair of scales. This was a strange idea, but they stood one foot to each scale. The idea was that they should register exactly half their weight on each scale, thereby confirming the correct standing posture. I would never have thought that posture could have been measured in such a way. Nevertheless, contests like this were pretty common. The idea was to polish the reputation of the chiropractic profession which had been considered “quackish” in those days. Basically, chiropractic had a serious public relations problem. They held no medical license and so carried little weight in the medical community, according to Dr P Reginald Hug, who is a past president of the Association for the History of Chiropractic. Hugs says, “We were the new kids on the block and medicine didn’t like us.”

To improve their plight, they began crowning posture queens. That way, the chiropractors could build goodwill without making waves with traditional doctors. Hugs says, “It was a way to get PR that was kind of middle of the road.” The point being made was that good posture leads to good health. And chiropractors were the people

to get you on the right track. That May, the judges crowned Lois Conway, 18, Miss Correct Posture. Second place went to Marianne Caba, 16, according to an account in the Chicago Tribune. Ruth Swenson, 26, came in third. The contests date back to the 1920s, but they became the rage during the 1950s and 1960s. The contestants were typically judged on beauty and poise, posture, and X-rays to evaluate their spinal structure. That was allowed then, because “In those days, nobody was concerned about radiation,” Hug says. We have learned much since then. We have also changed our thought…for the most part anyway…concerning chiropractic, and many people see a chiropractor on a regular basis, although, I doubt if the beauty pageants have continued at the conventions.

to get you on the right track. That May, the judges crowned Lois Conway, 18, Miss Correct Posture. Second place went to Marianne Caba, 16, according to an account in the Chicago Tribune. Ruth Swenson, 26, came in third. The contests date back to the 1920s, but they became the rage during the 1950s and 1960s. The contestants were typically judged on beauty and poise, posture, and X-rays to evaluate their spinal structure. That was allowed then, because “In those days, nobody was concerned about radiation,” Hug says. We have learned much since then. We have also changed our thought…for the most part anyway…concerning chiropractic, and many people see a chiropractor on a regular basis, although, I doubt if the beauty pageants have continued at the conventions.

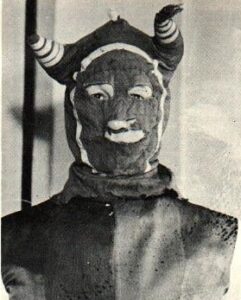

Vigilantism has probably always existed, at least as long as laws have existed. It is the epitome of taking the law into your own hands. One vigilante group called themselves “The Bald Knobbers.” They were a group of vigilantes in the Ozark region of southwest Missouri, from 1885 to 1889. The group got its name from the grassy bald knob summits of the nearby Ozark Mountains. The hill where they first met, Snapp’s Bald, is located just north of Kirbyville, Missouri. The Bald Knobbers were a strange looking bunch. They were known to wear black horned hoods with white outlines of faces painted on them. It was a distinction that evolved during the rapid growth of the group into neighboring counties from its Taney County origins.

Vigilantism has probably always existed, at least as long as laws have existed. It is the epitome of taking the law into your own hands. One vigilante group called themselves “The Bald Knobbers.” They were a group of vigilantes in the Ozark region of southwest Missouri, from 1885 to 1889. The group got its name from the grassy bald knob summits of the nearby Ozark Mountains. The hill where they first met, Snapp’s Bald, is located just north of Kirbyville, Missouri. The Bald Knobbers were a strange looking bunch. They were known to wear black horned hoods with white outlines of faces painted on them. It was a distinction that evolved during the rapid growth of the group into neighboring counties from its Taney County origins.

The Bald Knobbers had mostly sided with the Union in the Civil War, and they were opposed by the Anti-Bald Knobbers, who for the most part had sided with the Confederates. After the Civil War, the economy in Southwest Missouri was failing. Taxes were high. Lawlessness, disorder, and a general breakdown of society prevailed, especially in small towns and rural regions. The rising crime rate was the reason the group was formed. The area was in a deplorable state when Nathaniel N Kinney settled in Taney County, Missouri, in 1883. Outlaws and renegades ruled the land. Most of them were bushwhackers and guerillas that had rampaged through Missouri during the Civil War. Because law enforcement was at a minimum, the outlaws had free reign. To protect their own, clans elected and controlled the local sheriff, whose authority was to subpoena jury panels. If outlaws or their relatives didn’t sit on the juries, they bribed those who did. As many as forty murders occurred in Taney County between 1865 and 1885, but due to all the corruption, not a single suspect was convicted.

Nat Kinney was about to change all that. Kinney feared no man. He stood six feet six and weighed more than 300 pounds. On September 22, 1883, after yet another murder Kinney began to consider forming a law-and-order league patterned after other vigilante groups that were popular during that time. The final straw came when a biased jury acquitted yet another murderer, Kinney called together 12 county leaders who met in secret. They decided to form a committee to fight the lawlessness and elect officials who would enforce the law, and the Bald Knobbers group was born. The Bald Knobbers began with “good intentions,” but soon, the violence displayed by the vigilante group gained national attention, becoming more publicized than the actual fight for law and order.

It seemed that a lot of people wanted to get better control of the lawless situation in the area, so the organization grew rapidly, and by the time of their meeting on April 5, 1885, two hundred people showed up at a meeting on Snapp’s Bald, a hilltop south of Forsyth, Missouri. Kinney was an excellent speaker and was unanimously elected as their leader. Kinney accepted and swore his followers to secrecy. Then, he instructed them to recruit new members to carry out the group’s ultimate goal of taking control of a wildly out of control situation. Within days, they were ready. The Bald Knobbers began to show their force when over 100 of them broke open the door of the Taney County jail and kidnapped brothers, Frank and Tubal Taylor. The Taylor brothers were well known criminals in the area and were known for their viciousness. They were jailed for wounding a storekeeper during an argument over credit for a pair of boots. Unfortunately for the Taylor brothers, the local store owner, John Dickenson, happened to be a Bald Knobber. The group broke the two out of jail. Then the mob hauled the brothers south of Forsyth and hanged them. They were not going to have a corrupt trial this time.

Some of the Bald Knobbers felt that the groups own violence was appalling, and so they dropped out of the group after the attack. Nevertheless, the Bald Knobbers continued to grow, and before long, the group had between 500 and 1,000 members. Kinney’s group began to further “correct” the lawlessness by making night rides to scare such “lowlifes” as drunks, gamblers, or “loose” women into changing their ways. They also frightened wife beaters, couples “living in sin,” and men who failed to support their families. They had really gone overboard in their “correcting” of the people. The group actually took on the feel of a dictator, even trying to rule over those whose “crimes” were hurting no one. At this point, the Bald Knobbers split into two factions…those who followed or supported Kinney and those who thought him a tyrant and wished he was dead.

The violence brought about by the group increased as they flogged or branded suspected thieves, arsonists, and robbers. Their punishments no longer fit the crimes, as they would hang or beat a man to death for assault, disturbing the peace, or destroying property. Then things went from bad to worse when, emboldened by their power, some Bald Knobbers began to use their position for greedy and selfish purposes as they went after men who owed them money or owned land they wanted. They “settled” feuds over fence lines and property deeds, whipped men for disrupting services in their churches, or for supporting the wrong candidate in the election. They were quickly becoming the dictators of the area.

However, the harshest punishment was saved for those who spoke out against them. Some victims who resisted the Bald Knobbers simply disappeared. Later, several turned up in the woods, beaten to death. Those who lived to tell claimed that Kinney’s followers killed more than thirty men and at least four women. It is thought, however, that a better estimate, thought to be more realistic places the number between fifteen and eighteen. No matter, because the killing of anyone without a trial, unless it is in self-defense or the defense of another, is morally wrong. I understand how people can feel that justice isn’t being carried out, but when we take the law into our own hands, we are no different than the criminals we are trying to punish.

As the Bald Knobbers grew in numbers and their violent acts escalated, resentment grew, a a small group formed to fight against the Bald Knobbers. They called themselves the Anti-Bald Knobbers. The vigilantes were able to block every effort to mitigate the situation. The courthouse was burned down when a judge called for a state audit to ferret corruption among the county’s officeholders. Finally, twenty Bald Knobbers were arrested,

but most received light sentences ranging from fines to short prison terms. However, four were sentenced to death. On August 20, 1888, Nat Kinney was shot and killed by Billy Miles, a member of the Anti-Bald Knobbers, in a planned assassination. Though Miles was tried for Kinney’s murder, he was found not guilty based on self-defense and so ended a brutal reign of vigilante terror.

but most received light sentences ranging from fines to short prison terms. However, four were sentenced to death. On August 20, 1888, Nat Kinney was shot and killed by Billy Miles, a member of the Anti-Bald Knobbers, in a planned assassination. Though Miles was tried for Kinney’s murder, he was found not guilty based on self-defense and so ended a brutal reign of vigilante terror.