History

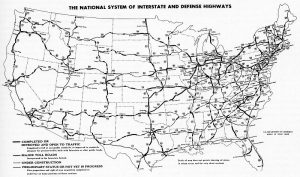

Prior to 1956, the road and highway system in the United States, well…lets just say, it left something to be desired…like passable roads for instance. Yes, there were a few highways, but on June 29, 1956, President Dwight Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. This bill changed the highways by creating a 41,000-mile “National System of Interstate and Defense Highways” that would, according to Eisenhower, eliminate unsafe roads, inefficient routes, traffic jams and all of the other things that got in the way of “speedy, safe transcontinental travel.” At the same time, highway advocates argued, “in case of atomic attack on our key cities, the road net [would] permit quick evacuation of target areas.” The 1956 law, which allocated more than $30 billion for the construction, declared that the construction of an elaborate expressway system was “essential to the national interest.” The plan included a lot of discussion on things like where exactly the highways should be built, and how much of the cost should be carried by the federal government versus the individual states. Several competing bills went through Congress before 1956, like the ones spearheaded by the retired general and engineer Lucius D Clay, Senator Albert Gore Sr, and Representative George H Fallon, who called his program the “National System of Interstate and Defense Highways,” thereby linking the nationwide construction of highways with the preservation of a strong national defense.

Prior to 1956, the road and highway system in the United States, well…lets just say, it left something to be desired…like passable roads for instance. Yes, there were a few highways, but on June 29, 1956, President Dwight Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. This bill changed the highways by creating a 41,000-mile “National System of Interstate and Defense Highways” that would, according to Eisenhower, eliminate unsafe roads, inefficient routes, traffic jams and all of the other things that got in the way of “speedy, safe transcontinental travel.” At the same time, highway advocates argued, “in case of atomic attack on our key cities, the road net [would] permit quick evacuation of target areas.” The 1956 law, which allocated more than $30 billion for the construction, declared that the construction of an elaborate expressway system was “essential to the national interest.” The plan included a lot of discussion on things like where exactly the highways should be built, and how much of the cost should be carried by the federal government versus the individual states. Several competing bills went through Congress before 1956, like the ones spearheaded by the retired general and engineer Lucius D Clay, Senator Albert Gore Sr, and Representative George H Fallon, who called his program the “National System of Interstate and Defense Highways,” thereby linking the nationwide construction of highways with the preservation of a strong national defense.

For President Eisenhower, however, who had participated in the United States Army’s first transcontinental motor convoy in 1919, during World War II, there was a realization that the country needed a better highway system. He had seen Germany’s Autobahn network, and admired the efficiency of it. In January 1956, Eisenhower repeated his 1954 State of the Union address call for a “modern, interstate highway system.” Later that month, Fallon introduced a revised version of his bill as the Federal Highway Act of 1956. It provided for a 41,000 mile national system of interstate and defense highways to be built over 13 years, with the federal government paying for 90 percent, or $24.8 billion. To raise funds for the project, Congress increased the gas tax from two to three cents per gallon and impose a series of other highway user tax changes. On June 26, 1956, the Senate approved the final version of the bill by a vote of 89 to 1. Senator Russell Long, who opposed the gas tax increase, cast the single “no” vote. That same day, the House approved the bill by a voice vote, and three days later, Eisenhower signed it into law.

The highway construction began almost immediately. With the construction came the employment of tens of thousands of workers and the use of billions of tons of gravel and asphalt. The system fueled a surge in the interstate trucking industry. That was good, but soon it pushed aside the railroads to gain the lion’s share of the domestic shipping market. Interstate highway construction also fostered the growth of roadside businesses such as restaurants, most of which were fast-food chains, hotels and amusement parks. By the 1960s, an estimated one in seven Americans was employed directly or indirectly by the automobile industry. Not only

that, but America had become a nation of drivers. Legislation has extended the Interstate Highway Revenue Act three times. Many historians say it is Eisenhower’s greatest domestic achievement. Many called the years between 1956 and 1966 “the Greatest Decade.” Still, critics of the system have pointed to its less positive effects, including the loss of productive farmland and the demise of small businesses and towns in more isolated parts of the country. I suppose that’s true, but it was inevitable.

that, but America had become a nation of drivers. Legislation has extended the Interstate Highway Revenue Act three times. Many historians say it is Eisenhower’s greatest domestic achievement. Many called the years between 1956 and 1966 “the Greatest Decade.” Still, critics of the system have pointed to its less positive effects, including the loss of productive farmland and the demise of small businesses and towns in more isolated parts of the country. I suppose that’s true, but it was inevitable.

In years gone by, US Route 66 was also known as the Will Rogers Highway, the Main Street of America, or the Mother Road. It was one of the original highways within the US Highway System. US Highway 66 was established on November 11, 1926, with road signs erected the following year. The highway became one of the most famous roads in the United States, and originally ran from Chicago, Illinois, through Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona before ending at Santa Monica, California, covering a total of 2,448 miles. It was highlighted by both the hit song “(Get Your Kicks) on Route 66” and the Route 66 television show in the 1960s, and later, “Wild Hogs.” After 59 years, on June 27, 1985, when the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials decertified the road and removed all its highway signs, and the famous Route 66 entered the realm of history.

In years gone by, US Route 66 was also known as the Will Rogers Highway, the Main Street of America, or the Mother Road. It was one of the original highways within the US Highway System. US Highway 66 was established on November 11, 1926, with road signs erected the following year. The highway became one of the most famous roads in the United States, and originally ran from Chicago, Illinois, through Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona before ending at Santa Monica, California, covering a total of 2,448 miles. It was highlighted by both the hit song “(Get Your Kicks) on Route 66” and the Route 66 television show in the 1960s, and later, “Wild Hogs.” After 59 years, on June 27, 1985, when the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials decertified the road and removed all its highway signs, and the famous Route 66 entered the realm of history.

The idea of building a highway along this route was first mentioned in Oklahoma in the mid-1920s. It was a way to link Oklahoma to cities like Chicago and Los Angeles. Highway Commissioner Cyrus Avery said that it would also be a way of diverting traffic from Kansas City, Missouri and Denver. In 1926, the highway earned its official designation as Route 66. The diagonal course of Route 66 linked hundreds of mostly rural communities to the cities along its route. This was to allow farmers to have an easy transport route for grain and other types of produce for distribution to the cities. In the 1930s, the long-distance trucking industry used it as a way of competing with the railroad for dominance in the shipping market.

During the Dust Bowl years of the 1930s, Route 66 was the scene of a mass westward migration, when more than 200,000 people traveled east from poverty-stricken, drought-ridden areas of California. John Steinbeck immortalized the highway in his classic 1939 novel “The Grapes of Wrath.” Beginning in the 1950s, the building of a massive system of interstate highways made older roads increasingly obsolete, and by 1970, modern four lane

highways had bypassed nearly all sections of Route 66. In October 1984, Interstate 40 bypassed the last original stretch of Route 66 at Williams, Arizona. According to the National Historic Route 66 Federation, drivers can still use 85 percent of the road, and Route 66 has become a destination for tourists from all over the world. After watching Wild Hogs, Bob and I became two of the many tourists who did drive a little bit of it when we drove to Madrid, New Mexico as part of our vacation, doing all the touristy things.

highways had bypassed nearly all sections of Route 66. In October 1984, Interstate 40 bypassed the last original stretch of Route 66 at Williams, Arizona. According to the National Historic Route 66 Federation, drivers can still use 85 percent of the road, and Route 66 has become a destination for tourists from all over the world. After watching Wild Hogs, Bob and I became two of the many tourists who did drive a little bit of it when we drove to Madrid, New Mexico as part of our vacation, doing all the touristy things.

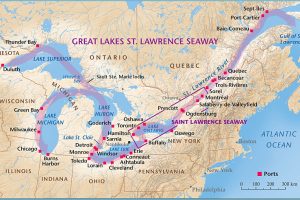

Most people know about the Great Lakes in the north-central United States, but quite possibly, many are not as familiar with the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Nevertheless, the Saint Lawrence Seaway is one of the most important parts of the Great Lakes shipping system. Prior to the Saint Lawrence Seaway there were a number of other canals. In 1871, there were locks on the Saint Lawrence River that allowed transit of vessels 186 feet long, 44 feet 6 inch wide, and 9 feet deep. The First Welland Canal, constructed from 1824–1829, had a minimum lock size of 110 feet long, 22 feet wide, and 8 feet deep, but it was generally too small to allow passage of larger ocean-going ships, which would have eliminated the majority of ships that could ship in quantity. The Welland Canal’s minimum lock size was increased to 150 feet long, 26.5 feet wide, and 9 feet deep for the Second Welland Canal, then to 270 feet long, 45 feet wide, and 14 feet deep with the Third Welland Canal, and to 766 feet long, 80 feet wide, and 30 feet deep with the fourth and current Welland Canal. Still, everyone knew that something else was going to have to be done soon.

Most people know about the Great Lakes in the north-central United States, but quite possibly, many are not as familiar with the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Nevertheless, the Saint Lawrence Seaway is one of the most important parts of the Great Lakes shipping system. Prior to the Saint Lawrence Seaway there were a number of other canals. In 1871, there were locks on the Saint Lawrence River that allowed transit of vessels 186 feet long, 44 feet 6 inch wide, and 9 feet deep. The First Welland Canal, constructed from 1824–1829, had a minimum lock size of 110 feet long, 22 feet wide, and 8 feet deep, but it was generally too small to allow passage of larger ocean-going ships, which would have eliminated the majority of ships that could ship in quantity. The Welland Canal’s minimum lock size was increased to 150 feet long, 26.5 feet wide, and 9 feet deep for the Second Welland Canal, then to 270 feet long, 45 feet wide, and 14 feet deep with the Third Welland Canal, and to 766 feet long, 80 feet wide, and 30 feet deep with the fourth and current Welland Canal. Still, everyone knew that something else was going to have to be done soon.

The first proposals for a bi-national comprehensive deep waterway along the Saint Lawrence were made in the 1890s. In the following decades, developers proposed a hydropower project that would be inseparable from the seaway,  the various governments and seaway supporters believed that the deeper water to be created by the hydro project was necessary to make the seaway channels feasible for ocean-going ships, which we all know was an essential part of the shipping business for the United States and the world. United States proposals for development up to and including World War I met with little interest from the Canadian federal government…at least at first. Later, the two national governments submitted Saint Lawrence plans to a group for study. By the early 1920s, both The Wooten-Bowden Report and the International Joint Commission recommended the project.

the various governments and seaway supporters believed that the deeper water to be created by the hydro project was necessary to make the seaway channels feasible for ocean-going ships, which we all know was an essential part of the shipping business for the United States and the world. United States proposals for development up to and including World War I met with little interest from the Canadian federal government…at least at first. Later, the two national governments submitted Saint Lawrence plans to a group for study. By the early 1920s, both The Wooten-Bowden Report and the International Joint Commission recommended the project.

The Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King really wasn’t all for the project, mostly because of opposition to the project in Quebec, in 1932. He and the United States representative finally signed a treaty of intent. The treaty was submitted to the United States Senate in November of 1932 and hearings continued until a vote was taken on March 14, 1934. The majority did vote in favor of the treaty, but it failed to gain the necessary two-thirds vote for ratification. Additional attempts between the governments in the 1930s to forge an agreement Failed due to opposition by the Ontario government of Mitchell Hepburn, and that of Quebec. In 1936, John C Beukema, who was the head of the Great Lakes Harbors Association and a member of the Great Lakes Tidewater Commission, was among a delegation of eight from the Great Lakes states to meet at the White House with United States President Franklin D Roosevelt to get his support for the Seaway project.

After much back and forth wrangling, the two countries agreed that the Saint Lawrence Seaway was a  necessary addition to the Great Lakes shipping industry, and it would later prove to be a vital part of it. In the years that my sister, my parents, and I lived in Superior, Wisconsin, the Saint Lawrence Seaway was something that, at least our parents remember being under construction. The opening ceremony took place on June 26, 1959, and was presided over by United States President Dwight D Eisenhower and Queen Elizabeth II. Once it was opened, it created a navigational channel from the Atlantic Ocean to all the Great Lakes. The seaway, made up of a system of canals, locks, and dredged waterways, extends a distance of nearly 2,500 miles, from the Atlantic Ocean through the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to Duluth, Minnesota, on Lake Superior.

necessary addition to the Great Lakes shipping industry, and it would later prove to be a vital part of it. In the years that my sister, my parents, and I lived in Superior, Wisconsin, the Saint Lawrence Seaway was something that, at least our parents remember being under construction. The opening ceremony took place on June 26, 1959, and was presided over by United States President Dwight D Eisenhower and Queen Elizabeth II. Once it was opened, it created a navigational channel from the Atlantic Ocean to all the Great Lakes. The seaway, made up of a system of canals, locks, and dredged waterways, extends a distance of nearly 2,500 miles, from the Atlantic Ocean through the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to Duluth, Minnesota, on Lake Superior.

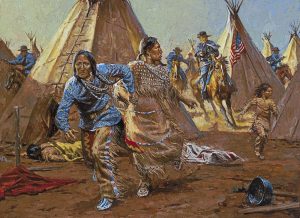

When Colorado Governor John Evans was looking to win a seat in the United States Senate, he made a bold, but unwise decision to attempt to remove all Native American activity in eastern Colorado Territory. On June 24, 1864, he warned that all peaceful Indians in the region must report to the Sand Creek reservation or risk being attacked. It was truly a halfhearted offer of sanctuary, with an ulterior motive. Evans then made one bad decision after another, when he issued a second proclamation that invited white settlers to indiscriminately “kill and destroy all…hostile Indians.” At the same time, Evans began creating a temporary 100-day militia force to wage war on the Indians. He placed the new regiment under the command of Colonel John Chivington, another ambitious man who hoped to gain high political office by fighting Indians.

When Colorado Governor John Evans was looking to win a seat in the United States Senate, he made a bold, but unwise decision to attempt to remove all Native American activity in eastern Colorado Territory. On June 24, 1864, he warned that all peaceful Indians in the region must report to the Sand Creek reservation or risk being attacked. It was truly a halfhearted offer of sanctuary, with an ulterior motive. Evans then made one bad decision after another, when he issued a second proclamation that invited white settlers to indiscriminately “kill and destroy all…hostile Indians.” At the same time, Evans began creating a temporary 100-day militia force to wage war on the Indians. He placed the new regiment under the command of Colonel John Chivington, another ambitious man who hoped to gain high political office by fighting Indians.

The Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe Indians of eastern Colorado had no idea of the political maneuverings of the White Man. Although some bands had violently resisted white settlers in years past, by the autumn of 1864 many Indians were becoming more receptive to Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle’s argument that they must make peace. Black Kettle had recently returned from a visit to Washington, DC, where President Abraham Lincoln had given him a huge American flag of which Black Kettle was very proud. He had seen the vast numbers of the white people and their powerful machines. The Indians, Black Kettle argued, must make peace or be crushed.

Word of Governor Evans’ June 24 offer of sanctuary was not well received by many of the Indians, most of whom still distrusted the White Man and were unwilling to give up the fight. Only Black Kettle and a few of the  lesser chiefs took Evans up on his offer of amnesty. Evans and Chivington were reluctant to see hostilities further abate before they had won a glorious victory, so they weren’t overjoyed that Black Kettle and his people accepted the offer. Nevertheless, they grudgingly promised Black Kettle that his people would be safe, if they came to Fort Lyon in eastern Colorado. In November 1864, the Indians reported to the fort as requested. Major Edward Wynkoop, the commanding federal officer, told Black Kettle to settle his band about 40 miles away on Sand Creek, where he promised they would be safe.

lesser chiefs took Evans up on his offer of amnesty. Evans and Chivington were reluctant to see hostilities further abate before they had won a glorious victory, so they weren’t overjoyed that Black Kettle and his people accepted the offer. Nevertheless, they grudgingly promised Black Kettle that his people would be safe, if they came to Fort Lyon in eastern Colorado. In November 1864, the Indians reported to the fort as requested. Major Edward Wynkoop, the commanding federal officer, told Black Kettle to settle his band about 40 miles away on Sand Creek, where he promised they would be safe.

Unfortunately, Wynkoop could not control John Chivington, and John Chivington was not inclined to honor the promise of safety. By November, the 100-day enlistment of the soldiers in his Colorado militia was nearly up, and Chivington hadn’t killed any of the Indians. With his political stock falling rapidly, and he seemed almost insane in his desire to kill Indians. “I long to be wading in gore!” he is said to have proclaimed at a dinner party. In his demented state, Chivington apparently decided that it did not matter whether he killed peaceful or hostile Indians. In his mind, Black Kettle’s village on Sand Creek became a legitimate and easy target, and he assumed that no one would ever know the difference.

Chivington led 700 men, many of them drunk, in a daybreak raid on Black Kettle’s peaceful village on November 29, 1864. Most of the Cheyenne warriors were away hunting. In the horrific hours that followed, Chivington and his men brutally slaughtered 105 women and children and killed 28 men. The soldiers scalped and mutilated the corpses, carrying body parts back to display in Denver as trophies. Somehow, Black Kettle and a number of other Cheyenne managed to escape. Chivington’s treachery would not go unnoticed as he had supposed, and in the following months, the nation learned of the horror of Sand Creek. Many Americans were

horrified and disgusted. Chivington and his soldiers had left the military and were beyond reach of a court martial. Still, Chivington’s horrific acts killed any chance of realizing his political ambitions, and he spent the rest of his inconsequential life wandering the West. Evans also paid a great price for the scandal. He was forced to resign as governor and his hopes of holding political office were dashed. Evans went on to a successful and lucrative career building and operating Colorado railroads, however. I suppose time can make people forget wrongs done, whether they should be forgotten or not.

horrified and disgusted. Chivington and his soldiers had left the military and were beyond reach of a court martial. Still, Chivington’s horrific acts killed any chance of realizing his political ambitions, and he spent the rest of his inconsequential life wandering the West. Evans also paid a great price for the scandal. He was forced to resign as governor and his hopes of holding political office were dashed. Evans went on to a successful and lucrative career building and operating Colorado railroads, however. I suppose time can make people forget wrongs done, whether they should be forgotten or not.

The Indian tribes didn’t usually have much use for the White Man, especially the ones who worked for the government. It seemed all they wanted to do was to herd the Indians onto the reservations and take away their lands, culture, and their language. This made the majority of Indians pretty angry, but President Calvin Coolidge was different than most government people. It wasn’t a matter of what he was able to accomplish, but rather what he wished he could accomplish, and maybe what he set the stage for…and mostly what the Indians knew was in his heart.

The Indian tribes didn’t usually have much use for the White Man, especially the ones who worked for the government. It seemed all they wanted to do was to herd the Indians onto the reservations and take away their lands, culture, and their language. This made the majority of Indians pretty angry, but President Calvin Coolidge was different than most government people. It wasn’t a matter of what he was able to accomplish, but rather what he wished he could accomplish, and maybe what he set the stage for…and mostly what the Indians knew was in his heart.

President Coolidge had made it very clear that, on personal moral grounds, he sincerely regretted the state of poverty to which many Indian tribes had sunk after decades of legal persecution and forced assimilation had been forced upon them. Coolidge made a public policy toward Indians, that included the Indian Citizen Act of 1924, which granted automatic United States citizenship to all American tribes, something that made perfect sense, since they had been here longer than the nation had existed. Nevertheless, during his two terms in office, while Coolidge  presented a public image as a strong proponent of tribal rights, the United States government policies of forced assimilation remained in full swing during his administration. At this time, all Indian children were placed in federally funded boarding schools in an effort to familiarize them with white culture and train them in marketable skills. During their schooling, they were separated from their families and stripped of their native language and culture, something that should never have happened, and something that has since been changed.

presented a public image as a strong proponent of tribal rights, the United States government policies of forced assimilation remained in full swing during his administration. At this time, all Indian children were placed in federally funded boarding schools in an effort to familiarize them with white culture and train them in marketable skills. During their schooling, they were separated from their families and stripped of their native language and culture, something that should never have happened, and something that has since been changed.

While not able to fix all the wrongs done to the Indians, Coolidge was still considered a friend of the Indians. In 1927, he planned a trip to the Black Hills region of North Dakota. In anticipation of the trip, the Sioux County Pioneer newspaper reported that a Sioux elder named Chauncey Yellow Robe, a descendant of Sitting Bull and an Indian school administrator, had suggested that Coolidge be inducted into the tribe. The article stated that  Yellow Robe graciously offered the president a “most sincere and hearty welcome” and hoped that Coolidge and his wife would enjoy “rest, peace, quiet and friendship among us.” Calvin Coolidge was very pleased at the offer, and decided to accept. This was not something that was offered to many people, so it was a great honor. The Sioux County Pioneer newspaper of North Dakota reported that on June 23, 1927 President Calvin Coolidge would be “adopted” into a Sioux tribe at Fort Yates on the south central border of North Dakota. At the Sioux ceremony in 1927, photographers captured Coolidge, in suit and tie, as he was given a grand ceremonial feathered headdress by Sioux Chief Henry Standing Bear and officially declared an honorary tribal member.

Yellow Robe graciously offered the president a “most sincere and hearty welcome” and hoped that Coolidge and his wife would enjoy “rest, peace, quiet and friendship among us.” Calvin Coolidge was very pleased at the offer, and decided to accept. This was not something that was offered to many people, so it was a great honor. The Sioux County Pioneer newspaper of North Dakota reported that on June 23, 1927 President Calvin Coolidge would be “adopted” into a Sioux tribe at Fort Yates on the south central border of North Dakota. At the Sioux ceremony in 1927, photographers captured Coolidge, in suit and tie, as he was given a grand ceremonial feathered headdress by Sioux Chief Henry Standing Bear and officially declared an honorary tribal member.

These days, every military veteran has available to them, a compensation package to thank them for their service. Returning servicemen have access to unemployment compensation, low-interest home and business loans, and…most importantly, funding for education, but this was not always the case. In fact, there was a time when returning veterans had to fight for bonuses they were supposed to receive, which brought about the 1932 Bonus March, in which 20,000 unemployed veterans and their families flocked in protest to Washington. I think most of us would agree that our veterans should not have to fight for the things promised to them for their service, after they have already spent time fighting for their country.

These days, every military veteran has available to them, a compensation package to thank them for their service. Returning servicemen have access to unemployment compensation, low-interest home and business loans, and…most importantly, funding for education, but this was not always the case. In fact, there was a time when returning veterans had to fight for bonuses they were supposed to receive, which brought about the 1932 Bonus March, in which 20,000 unemployed veterans and their families flocked in protest to Washington. I think most of us would agree that our veterans should not have to fight for the things promised to them for their service, after they have already spent time fighting for their country.

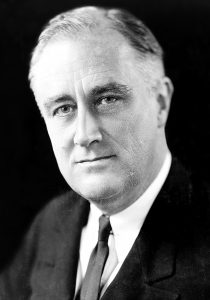

President Franklin D Roosevelt was responsible for the sweeping New Deal reforms, many of which were really not good for this nation or its people, but there was one part of that legislation that has been a good thing for returning veterans…the G.I. Bill. On this day June 22, 1944, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed the G.I. Bill. It was an unprecedented act of legislation designed to compensate returning members of the armed services, known as G.I.s, for their efforts in World War II. The G.I. Bill…officially the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944…was proposed in an effort to avoid a relapse into the Great Depression after the war ended. The American Legion, a veteran’s organization, successfully fought for many of the provisions included in the bill, which gave returning servicemen the compensations they now have. By giving veterans money for tuition, living expenses, books, supplies and  equipment, the G.I. Bill effectively transformed higher education in America. Before the war, college had been an option for only 10-15 percent of young Americans, and university campuses had become known as a haven for the most privileged classes. This was not what America was supposed to be about. By 1947, the contrast was striking. Veterans made up half of the nation’s college enrollment. Three years later, nearly 500,000 Americans graduated from college, compared with 160,000 in 1939. Sure, they had to serve their country, but for many young people, this was not only what they felt was their duty, but it also became a scholarship program.

equipment, the G.I. Bill effectively transformed higher education in America. Before the war, college had been an option for only 10-15 percent of young Americans, and university campuses had become known as a haven for the most privileged classes. This was not what America was supposed to be about. By 1947, the contrast was striking. Veterans made up half of the nation’s college enrollment. Three years later, nearly 500,000 Americans graduated from college, compared with 160,000 in 1939. Sure, they had to serve their country, but for many young people, this was not only what they felt was their duty, but it also became a scholarship program.

As educational institutions opened their doors to this diverse new group of students, overcrowded classrooms and residences prompted widespread improvement and expansion of university facilities and teaching staffs. The bill was not only good for the veterans, but also for the economy, as more teaching jobs were created. An array of new vocational courses were developed across the country, including advanced training in education, agriculture, commerce, mining and fishing…skills that had previously been taught only informally. Some of these classes are responsible for some of the jobs that everyday Americans, even those without college educations have held. Jobs such as mining, and farming, and even fishing became commonplace.

The G.I. Bill became one of the major forces for economic expansion in America that lasted 30 years after World War II. Only 20% of the money set aside for unemployment compensation under the bill was given out. Most veterans found jobs or pursued higher education. Low interest loans enabled millions of American families to move out of cities and buy or build homes outside the city, changing the face of the suburbs. Over 50 years, the impact of the G.I. Bill was enormous, with 20 million veterans and dependents using the education benefits and 14 million home loans guaranteed, for a total federal investment of $67 billion. Among the millions of Americans who have taken advantage of the bill are former Presidents George H.W. Bush and Gerald Ford, former Vice President Al Gore and entertainers Johnny Cash, Ed McMahon, Paul Newman and Clint Eastwood, and closer to home, my brother-in-law, Ron Schulenberg, as well as my nephew, Allen Beach and soon, his wife, Gabby.

Dependency on foreign oil has long been a problem for the United States, keeping us always at the mercy of foreign oil companies. When we are dependent on foreign oil, we are subject to their prices and their shortages, or their refusal to sell to us. This nation has always needed to be dependent on our own production of oil, and as an oil rich nation, there is no reason for us to look elsewhere for our oil supply. Of course, the environmentalists would disagree with me, and I don’t want oil spills any more than anyone else does. Still, foreign nations have us at a disadvantage, not to mention that oil production in the United States would provide a lot jobs in the United States.

Dependency on foreign oil has long been a problem for the United States, keeping us always at the mercy of foreign oil companies. When we are dependent on foreign oil, we are subject to their prices and their shortages, or their refusal to sell to us. This nation has always needed to be dependent on our own production of oil, and as an oil rich nation, there is no reason for us to look elsewhere for our oil supply. Of course, the environmentalists would disagree with me, and I don’t want oil spills any more than anyone else does. Still, foreign nations have us at a disadvantage, not to mention that oil production in the United States would provide a lot jobs in the United States.

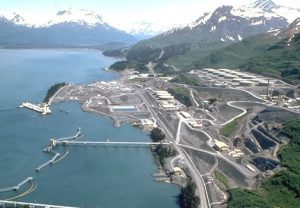

I’m not the only one who thinks this way either. In 1968, a massive oil field was discovered on the north coast of Alaska near Prudhoe Bay, which is north of the Arctic Circle, but the ice-packed waters of the Beaufort Sea are inaccessible to oil tankers. In 1972, the Department of the Interior authorized drilling there, and after the Arab oil embargo of 1973 plans moved quickly to begin construction of a pipeline. The Alyeska Pipeline Service Company was formed by a consortium of major oil companies, and in 1974 construction began. The steel pipeline is 48 inches in diameter, and it winds through 800 miles of Alaskan wilderness, crossing three Arctic mountain ranges and hundreds of rivers and streams. Environmentalists fought to prevent its construction, saying it would destroy a pristine ecosystem, but they were ultimately overruled by Congress, who saw it as a way of lessening America’s dependence on foreign oil. The trans-Alaska pipeline was the world’s largest privately funded construction project to that date, costing $8 billion and taking three years to build. The conservation groups argued that the pipeline would destroy caribou habitats in the Arctic, melt the fragile permafrost (which is permanently frozen subsoil), along its route, and pollute the salmon-rich waters of the Prince William Sound at Valdez. Under pressure, Alyeska agreed to extensive environmental precautions, including building 50% of the pipeline above the ground to protect the permafrost from the naturally heated crude oil and to permit passage of caribou underneath.

On June 20, 1977, with the flip of a switch in Prudhoe Bay, crude oil from the nation’s largest oil field began flowing south, down the trans-Alaska pipeline to the ice-free port of Valdez, Alaska. It wasn’t without its glitches, however. Power supply problems, a cracked section of pipe, faulty welds, and an unsuccessful dynamite attack on the pipeline outside of Fairbanks delayed the arrival of oil at Valdez for several weeks. Finally, in August, the first oil tanker left Valdez en route to the lower 48 states. The trans-Alaska pipeline was great for the Alaskan economy. Today, about 800,000 barrels move through the pipeline each day. Altogether, the pipeline has carried more than 14 billion barrels of oil in its lifetime. For its first decade of existence, the pipeline was quietly applauded as an environmental success, much to the chagrin of the environmentalists. Caribou populations in the vicinity of the pipeline actually grew, partly because many of the grizzly bears and wolves were scared off by the pipeline work, and the permafrost remained intact. The only major oil spill on land occurred when an unknown saboteur blew a hole in the pipe near Fairbanks, and 550,000 gallons of oil spilled onto the ground. Then, on March 24, 1989, the worst fears of environmentalists were realized when the Exxon Valdez ran aground in the Prince William Sound after filling up at the port of Valdez. Ten million gallons of oil were dumped into the water, devastating hundreds of miles of coastline. In the 1990s, the Alaskan oil enterprise drew further controversy when the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company attempted to cover up electrical and mechanical problems in the aging pipeline.

In 2001, President George W. Bush proposed opening a portion of the 19 million acre Arctic National Wildlife

Refuge, east of Prudhoe Bay, to oil drilling. The environmental groups immediately opposed the proposal and it was initially defeated. Then, in 2006, the Senate voted 51-49 in favor of a budget resolution that included billions for Arctic drilling. Environmental groups are still fighting the legislation. I think, drilling at home is the best way to protect American jobs, and our economy, and as we all know, it could certainly use a serious boost right now.

Refuge, east of Prudhoe Bay, to oil drilling. The environmental groups immediately opposed the proposal and it was initially defeated. Then, in 2006, the Senate voted 51-49 in favor of a budget resolution that included billions for Arctic drilling. Environmental groups are still fighting the legislation. I think, drilling at home is the best way to protect American jobs, and our economy, and as we all know, it could certainly use a serious boost right now.

Wars always bring changes…especially in how nations feel about other nations. Sometimes, the whole world seems to be against one nation that has proven itself to be particularly evil. Germany was one of those nations that the entire world was against during World War I, as well as during World War II. It was during World War I that Britain’s King George V was quite concerned about the anti-German sentiment that existed in the world and in Britain. His family was of German descent, and the family name was very much a German name…Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, to be exact.

Wars always bring changes…especially in how nations feel about other nations. Sometimes, the whole world seems to be against one nation that has proven itself to be particularly evil. Germany was one of those nations that the entire world was against during World War I, as well as during World War II. It was during World War I that Britain’s King George V was quite concerned about the anti-German sentiment that existed in the world and in Britain. His family was of German descent, and the family name was very much a German name…Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, to be exact.

George was born on June 3, 1865, the second son of Prince Edward of Wales, who later became King Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark, and the grandson of Queen Victoria. He embarked on a naval career before becoming heir to the throne in 1892 when his older brother, Edward, died of pneumonia. The following year, George married the German princess Mary of Teck, who was his cousin, a granddaughter of King George III, and who had previously been intended for Edward. The couple had six children, including the future Edward  VIII and George VI, who took the throne in 1936 after his brother abdicated to marry the American divorcee Wallis Simpson. As the new Duke of York, George had to abandon his career in the navy. He became a member of the House of Lords and received a political education. When his father died in 1910, George ascended to the British throne as King George V.

VIII and George VI, who took the throne in 1936 after his brother abdicated to marry the American divorcee Wallis Simpson. As the new Duke of York, George had to abandon his career in the navy. He became a member of the House of Lords and received a political education. When his father died in 1910, George ascended to the British throne as King George V.

With the outbreak of World War I in the summer of 1914, strong anti-German feeling within Britain caused sensitivity among the royal family about its German roots. Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, also a grandson of Queen Victoria, was the king’s cousin; the queen herself was German. Public respect for the king increased during World War One, when he made many visits to the front line, hospitals, factories and dockyards. Still, because of anti-German feeling George V felt led to adopt the family name of Windsor, so on June 19, 1917, the king decreed that the royal surname was thereby changed from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor, which it has remain since that day.

After the World War II, the current Prince Philip was granted permission by King George VI to marry the future Queen Elizabeth. Before the official announcement of their engagement, Philip abandoned his Greek and Danish royal titles and became a naturalized British subject, adopting the surname Mountbatten from his maternal grandparents. After an engagement of five months, he married Elizabeth on November 20, 1947. Just before  the wedding, Philip was made the Duke of Edinburgh. He left active military service when Elizabeth became monarch in 1952, having reached the rank of commander. He was formally made a British prince in 1957. Mountbatten-Windsor is the personal surname used by the male-line descendants of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Under a declaration made in Privy Council in 1960, the name Mountbatten-Windsor applies to male-line descendants of the Queen without royal styles and titles. Individuals with royal styles do not usually use a surname, but some descendants of the Queen with royal styles have used Mountbatten-Windsor when a surname was required.

the wedding, Philip was made the Duke of Edinburgh. He left active military service when Elizabeth became monarch in 1952, having reached the rank of commander. He was formally made a British prince in 1957. Mountbatten-Windsor is the personal surname used by the male-line descendants of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Under a declaration made in Privy Council in 1960, the name Mountbatten-Windsor applies to male-line descendants of the Queen without royal styles and titles. Individuals with royal styles do not usually use a surname, but some descendants of the Queen with royal styles have used Mountbatten-Windsor when a surname was required.

In a war, sometimes the best thing that can be done is to retreat, but that is not always easy to do. When the enemy is closing in and there seems no way of escape. Sometimes, a way of escape seems to come together in such a way that it almost seems miraculous…or maybe that is the only real explanation…a miracle. Such seemed to be the case with Britain both in Dunkirk, France, called Operation Dynamo, and again from Cherbourg, Saint Malo, Brest, and Nantes, dubbed Operation Aerial. The evacuation from Dunkirk, was most likely the largest of its kind, or at least up to that date. I suppose there might have been others since then, but I am not aware of any. During the evacuation of Dunkirk, the British managed to evacuate 338,226 soldiers…and almost unheard of amount of men were saved, by a coordinated effort using 860 boats. During Operation Ariel, another 191,870 troops were rescued, bringing the total of military and civilian personnel returned to Britain during the Battle of France to 558,032, including 368,491 British troops.

In a war, sometimes the best thing that can be done is to retreat, but that is not always easy to do. When the enemy is closing in and there seems no way of escape. Sometimes, a way of escape seems to come together in such a way that it almost seems miraculous…or maybe that is the only real explanation…a miracle. Such seemed to be the case with Britain both in Dunkirk, France, called Operation Dynamo, and again from Cherbourg, Saint Malo, Brest, and Nantes, dubbed Operation Aerial. The evacuation from Dunkirk, was most likely the largest of its kind, or at least up to that date. I suppose there might have been others since then, but I am not aware of any. During the evacuation of Dunkirk, the British managed to evacuate 338,226 soldiers…and almost unheard of amount of men were saved, by a coordinated effort using 860 boats. During Operation Ariel, another 191,870 troops were rescued, bringing the total of military and civilian personnel returned to Britain during the Battle of France to 558,032, including 368,491 British troops.

Operation Aerial began on June 15, 1940 and ended on June 25, 1940. Following the military collapse in the Battle of France against Nazi Germany, it became evident that Allied soldiers and civilians were in grave danger. With two-thirds of France now occupied by German troops, those British and Allied troops that had not participated in Operation Dynamo, the evacuation of Dunkirk, were shipped home, but there remained a concern for the areas from Cherbourg, St. Malo, Brest, and Nantes. While these men were not under the immediate threat of assault, as at Dunkirk, they were by no means safe, so Brits, Poles, and Canadian troops were rescued from occupied territory by boats sent from Britain. Meanwhile, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill offered words of encouragement in a broadcast to the nation, “Whatever has happened in France…we shall defend our island home, and with the British Empire we shall fight on unconquerable until the curse of Hitler is lifted.” This was his way of promising that Britain would never fall under Nazi rule.

Operation Aerial was split into two sectors. Admiral James, based at Portsmouth, was to control the evacuation from Cherbourg and St Malo, while Admiral Dunbar-Nasmith, the commander-in-chief of the Western Approaches, based at Plymouth, would control the evacuation from Brest, St. Nazaire and La Pallice. Eventually this western evacuation would extend to include the ports on the Gironde estuary, Bayonne and St Jean-de-Luz. Once the people were on board, I’m sure they thought they were finally safe, but that was not necessarily the case. The Germans attacked the rescue boats. Among those rescued from the shores of France, were 5,000 soldiers and French civilians on board the ocean liner Lancastria, which had picked them up at St. Nazaire. Germans bombers sunk the liner on June 17, 1940, and 3,000 passengers drowned. Churchill ordered that news of the Lancastria not be broadcast in Britain, fearing the effect it would have on public morale, since everyone was already worried about a possible German invasion now that only a channel separated them. The British public would eventually find out, but not for another six weeks, when the news broke in the United States. They would also receive the good news that Hitler had no immediate plans for an invasion of the British isle, “being well aware of the difficulties involved in such an operation,” reported the German High Command.

In the end, the evacuations dubbed Operation Dynamo and Operation Aerial, were successful, in that most of those who were evacuated made it home. I’m sure that the retreats did not feel like a success or a victory to the soldiers fighting in the Battle of France, but I am also sure that they were thankful to be among those who made it home. They would live to fight another day in the horrendous war that was World War II.

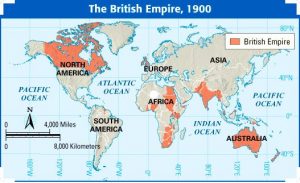

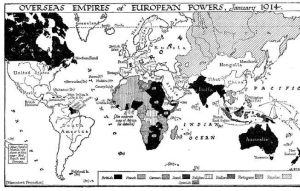

World wars are a complicated matter. There are multiple enemies, multiple allies, and the lines are not necessarily very clear. The one thing that always seems to be a constant, however, is territory. Imperialism…when a country takes over new lands or countries and makes them subject to their rule, played a big roll in World War I, as did industrialism. By 1900, any territorial gain by one power meant the loss of territory by another, and for Britain, the strongest of all the empires, that was a problem. Britain’s colonial territory was over 100 times the size of its own territory at home, thus giving rise to the phrase “the sun never sets on the British empire.” At this same time, France had control of large areas of Africa. With the rise of industrialism countries needed new markets. The amount of lands owned by Britain and France increased the rivalry with Germany who had entered the scramble to acquire colonies late and only had small areas of Africa.

World wars are a complicated matter. There are multiple enemies, multiple allies, and the lines are not necessarily very clear. The one thing that always seems to be a constant, however, is territory. Imperialism…when a country takes over new lands or countries and makes them subject to their rule, played a big roll in World War I, as did industrialism. By 1900, any territorial gain by one power meant the loss of territory by another, and for Britain, the strongest of all the empires, that was a problem. Britain’s colonial territory was over 100 times the size of its own territory at home, thus giving rise to the phrase “the sun never sets on the British empire.” At this same time, France had control of large areas of Africa. With the rise of industrialism countries needed new markets. The amount of lands owned by Britain and France increased the rivalry with Germany who had entered the scramble to acquire colonies late and only had small areas of Africa.

During this time Germany became concerned that Russia might try to take over their nation, so they signed a  treaty with Austria-Hungary to protect each other from Russia. The Dual Alliance was created by treaty on October 7, 1879 as part of Bismarck’s system of alliances to prevent or limit war. The two powers promised each other support in case of attack by Russia. Also, each state promised benevolent neutrality to the other if one of them was attacked by another European power, most likely France. Germany’s Otto von Bismarck saw the alliance as a way to prevent the isolation of Germany and to preserve peace, as Russia would not wage war against both empires. Then in 1881, Austria-Hungary made an alliance with Serbia to stop Russia from gaining control of Serbia. Before long alliances were popping up everywhere. Germany and Austria-Hungary made an alliance with Italy in 1882 that was dubbed The Triple Alliance to stop Italy from taking sides with Russia. Then in 1894, Russia formed an alliance with France called the Franco-Russian Alliance, to protect Russia against Germany and Austria-Hungary.

treaty with Austria-Hungary to protect each other from Russia. The Dual Alliance was created by treaty on October 7, 1879 as part of Bismarck’s system of alliances to prevent or limit war. The two powers promised each other support in case of attack by Russia. Also, each state promised benevolent neutrality to the other if one of them was attacked by another European power, most likely France. Germany’s Otto von Bismarck saw the alliance as a way to prevent the isolation of Germany and to preserve peace, as Russia would not wage war against both empires. Then in 1881, Austria-Hungary made an alliance with Serbia to stop Russia from gaining control of Serbia. Before long alliances were popping up everywhere. Germany and Austria-Hungary made an alliance with Italy in 1882 that was dubbed The Triple Alliance to stop Italy from taking sides with Russia. Then in 1894, Russia formed an alliance with France called the Franco-Russian Alliance, to protect Russia against Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Now at this point, I’m sure you feel as confused about all this as I did. To me, it seems like it would be very difficult to know who the enemy really was, and even if you knew, it was subject to change, depending on who they formed an alliance with. That is also why I was wondering why on June 16, 1918, the Battle of the Piave River was raging on the Italian front. Russia had bowed out of the war effort in early 1918, and Germany began  to pressure its ally, Austria-Hungary, to devote more resources to combating Italy. Wait…I thought Italy was their ally…apparently not so much. Specifically, the Germans wanted a major new offensive along the Piave River, located just a few kilometers from such important Italian urban centers as Venice, Padua and Verona. In addition to striking on the heels of Russia’s withdrawal, the offensive was intended as a follow-up to the spectacular success of the German-aided operations at Caporetto in the autumn of 1917. Wars really seem to be quite senseless, but when Imperialistic nations try to expand their territories, I guess, alliances can be made and broken quite easily.

to pressure its ally, Austria-Hungary, to devote more resources to combating Italy. Wait…I thought Italy was their ally…apparently not so much. Specifically, the Germans wanted a major new offensive along the Piave River, located just a few kilometers from such important Italian urban centers as Venice, Padua and Verona. In addition to striking on the heels of Russia’s withdrawal, the offensive was intended as a follow-up to the spectacular success of the German-aided operations at Caporetto in the autumn of 1917. Wars really seem to be quite senseless, but when Imperialistic nations try to expand their territories, I guess, alliances can be made and broken quite easily.