History

Would you want your nation to go to war over fish? Would you even consider that nations might do that? Well, enter the Cod Wars. The Cod Wars were disputes over Iceland’s territorial waters, fought in four bouts over a 25 year period: The Proto Cod War, between 1952 and 1956; the First Cod War between 1958 and 1961; the Second Cod War between 1972 and 1973; and the Third Cod War between 1975 and 1976. Iceland wanted to expand its territorial waters and exclude foreign fishing fleets. Britain would have none of that. The British distant fishing fleet fished extensively in the waters off Iceland, and supplied a lot of fish and chips shops. But Britain also wanted to prevent precedents that violated the principle of narrow territorial waters. Narrow territorial waters were key for the Royal Navy to sail freely and continue to project power across the world. The Icelanders were motivated by the prospective economic gains. An extension of its territorial waters meant greater catches, and a way to exclude competing trawler fleets and conserve important fishing grounds. The country’s heavy dependence on fishing meant that extensions had a significant impact on Iceland’s Gross Domestic Product, roughly one-quarter of which was tied to the fisheries sector, export earnings one-half to two-thirds of which were tied to the fisheries sector and employment roughly 15 percent of which was in the fisheries sector.

Would you want your nation to go to war over fish? Would you even consider that nations might do that? Well, enter the Cod Wars. The Cod Wars were disputes over Iceland’s territorial waters, fought in four bouts over a 25 year period: The Proto Cod War, between 1952 and 1956; the First Cod War between 1958 and 1961; the Second Cod War between 1972 and 1973; and the Third Cod War between 1975 and 1976. Iceland wanted to expand its territorial waters and exclude foreign fishing fleets. Britain would have none of that. The British distant fishing fleet fished extensively in the waters off Iceland, and supplied a lot of fish and chips shops. But Britain also wanted to prevent precedents that violated the principle of narrow territorial waters. Narrow territorial waters were key for the Royal Navy to sail freely and continue to project power across the world. The Icelanders were motivated by the prospective economic gains. An extension of its territorial waters meant greater catches, and a way to exclude competing trawler fleets and conserve important fishing grounds. The country’s heavy dependence on fishing meant that extensions had a significant impact on Iceland’s Gross Domestic Product, roughly one-quarter of which was tied to the fisheries sector, export earnings one-half to two-thirds of which were tied to the fisheries sector and employment roughly 15 percent of which was in the fisheries sector.

Each Cod War broke out when Iceland extended its territorial waters and the British failed to comply with the new Icelandic regulations. Clashes and confrontations started between Icelandic patrol ships and British trawlers. The harassment of British trawlers in the contested waters provoked the British to sanction the Icelanders in the Proto Cod War preventing the Icelanders from accessing their largest export market and send the Royal Navy into the contested waters during the last three Cod Wars. Neither side actively tried to cause casualties but the clashes at sea were still dangerous. I can’t imagine a war, in which the combatants try not to  hurt each other. Nevertheless, individuals were injured, and there was one fatality on the Icelandic side. Surely bargaining would have saved both sides the inevitable costs and risks of unilateral, unrecognized expansions. Historians and political scientists have identified how domestic pressure on elites and the nature of alliance politics contributed to miscalculation on both sides that contributed to bargaining failure.

hurt each other. Nevertheless, individuals were injured, and there was one fatality on the Icelandic side. Surely bargaining would have saved both sides the inevitable costs and risks of unilateral, unrecognized expansions. Historians and political scientists have identified how domestic pressure on elites and the nature of alliance politics contributed to miscalculation on both sides that contributed to bargaining failure.

Neither government really understood the public pressure that their counterparts were under. Icelandic politicians were particularly vulnerable to domestic pressure, as opposition parties, media and public sentiment likened compromise to treason. Contradictory statements from different members of the Icelandic government, diplomats and other elites contributed to the mistaken British view that the Icelanders were divided and not fully committed to expansive and legally dubious extensions. The British trawling industry, which had a staunch ally in the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, put great pressure on the British government. The Ministry favored aggressive and extreme actions in the disputes, while the Foreign Office was more conciliatory and concerned about the Cod Wars’ impact on British security interests and international standing. The Icelanders deemed it unlikely that their NATO ally and friend would sanction the Icelanders or send in the Royal Navy. Both sides also believed that the United States and other NATO allies would side with them. Even though the American position on territorial waters tended to line up with the British view, and the United States opposed Iceland’s unilateralism, the United States ultimately intervened on Iceland’s behalf. They had a stake in the outcome. The United States bought up unsold Icelandic fish, making the British sanctions toothless in the Proto Cod War. The United States pressured Britain behind the scenes in the last three Cod Wars. At stake was a strategically important United States base in Keflavík, which was needed to track Soviet submarine activity. For the United States, Iceland was an important chain in the line of defense in case of war with the Soviet Union.

Neither Iceland or Britain found the other’s threats and demands credible prior to the outbreak of conflict. However, as each Cod War intensified and Icelandic statesmen came under major domestic pressure, they found themselves forced to threaten to withdraw Iceland’s NATO membership and expel United States forces from the military base in Keflavík in desperate attempts to push the British to give in to Iceland’s demands.  What started as minor disputes over fishing rights suddenly had implications for the Cold War. President Eisenhower…during the Proto Cod War…and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger…during the Second Cod War…talked about the Icelanders in terms of the “tyranny of the weak,” as they felt compelled to oblige their small, obstinate, strategically important ally. With NATO allies heaping pressure on the British. to settle and Icelandic politicians clearly constrained by public pressure, the British reluctantly gave in to most of the Icelanders’ demands. Iceland achieved favorable agreements in each Cod War, with the last Cod War concluding 40 years ago when the Icelanders achieved a 200-mile exclusive economic zone.

What started as minor disputes over fishing rights suddenly had implications for the Cold War. President Eisenhower…during the Proto Cod War…and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger…during the Second Cod War…talked about the Icelanders in terms of the “tyranny of the weak,” as they felt compelled to oblige their small, obstinate, strategically important ally. With NATO allies heaping pressure on the British. to settle and Icelandic politicians clearly constrained by public pressure, the British reluctantly gave in to most of the Icelanders’ demands. Iceland achieved favorable agreements in each Cod War, with the last Cod War concluding 40 years ago when the Icelanders achieved a 200-mile exclusive economic zone.

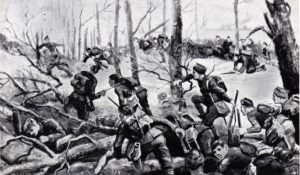

As a young battalion commander, Winston Churchill had a lot to learn about the facts of war. He was destined for greatness, and if he was to realize his destiny, he would have to learn many things. On January 17, 1916, he was battalion commander on the Western Front, when he attended a lecture on the Battle of Loos given by his friend, Colonel Tom Holland, in the Belgian town of Hazebrouck. It would be one of the first lessons, but the resulting knowledge might not be what we all would think. It was not about strategy or brave heroics, but rather of hopelessness.

As a young battalion commander, Winston Churchill had a lot to learn about the facts of war. He was destined for greatness, and if he was to realize his destiny, he would have to learn many things. On January 17, 1916, he was battalion commander on the Western Front, when he attended a lecture on the Battle of Loos given by his friend, Colonel Tom Holland, in the Belgian town of Hazebrouck. It would be one of the first lessons, but the resulting knowledge might not be what we all would think. It was not about strategy or brave heroics, but rather of hopelessness.

The Battle of Loos, which took place in September 1915, resulted in devastating casualties for the Allies and was taken by the British as a sign of the need to change their conduct of the war. In one major consequence, Sir John French was replaced by Sir Douglas Haig as British commander in the wake of that battle. “Tom spoke very well,” Churchill wrote to his wife, Clementine, “but his tale was one of hopeless failure, of sublime heroism utterly wasted and of splendid Scottish soldiers shorn away in vain with never the ghost of a chance of success. Afterwards they asked me what was the lesson of the lecture. I restrained an impulse to reply ‘Don’t do it again.’ But they will–I have no doubt.” What Churchill took away from the lecture was that in war, there is no winner…not really. There are losses on both sides, sometimes almost equal in number, so that the victory goes to the one who holds out the longest. Defeat comes in surrender.

Churchill had been demoted from First Lord of the Admiralty after the British plan to attempt a naval capture of the Turkish-controlled Dardanelle Straits met with resounding failure in mid-to-late 1915. Reduced to a minor ministerial position, Churchill resigned from the government in November 1915 and rejoined the army, heading  to the Western Front with the rank of lieutenant colonel. During his six months in Belgium, Churchill…who would later lead his country to victory in the World War II and be celebrated as the greatest political leader in British history, saw first-hand the hardships of war and the sacrifices that unknown, unheralded soldiers made for their country. More than once, he himself narrowly escaped death by an enemy shell. As he wrote to Clementine, “Twenty yards more to the left and no more tangles to unravel, no more anxieties to face, no more hatreds and injustices to encountera good ending to a chequered life, a final gift–unvalued–to an ungrateful country.” I find it amazing that a man so capable of “winning” a war, would count it as lost.

to the Western Front with the rank of lieutenant colonel. During his six months in Belgium, Churchill…who would later lead his country to victory in the World War II and be celebrated as the greatest political leader in British history, saw first-hand the hardships of war and the sacrifices that unknown, unheralded soldiers made for their country. More than once, he himself narrowly escaped death by an enemy shell. As he wrote to Clementine, “Twenty yards more to the left and no more tangles to unravel, no more anxieties to face, no more hatreds and injustices to encountera good ending to a chequered life, a final gift–unvalued–to an ungrateful country.” I find it amazing that a man so capable of “winning” a war, would count it as lost.

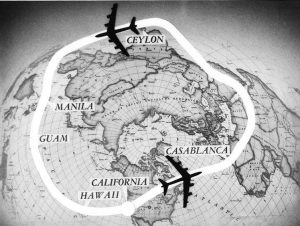

We all look for firsts in things, like first steps, first words, first man in space, first man on the moon, and in this case, the first around the world flight of a jet engine. You would expect that it might be some new jet, designed by an aviation expert, and you would be right, but the flight in question happened on January 16, 1957. The plans were three Boeing B-52 Stratofortresses. This was not just a flight for the purpose of setting a record, but rather it was a flight designed to prove a very important point. The operation was called Operation Power Flite…I’m not sure why flight was spelled flite. The planes made the trip around the world in 45 hours and 19 minutes, using in-flight refueling so that they could stay aloft for the entire journey. The mission was intended to demonstrate that the United States had the ability to drop a hydrogen bomb anywhere in the world. Led by Major General Archie J. Old, Jr. as flight commander, five B-52B aircraft of the 93rd Bombardment Wing of the 15th Air Force took off from Castle Air Force Base in California on January 16, 1957, at 1:00 PM, with two of the planes flying as spares. Old was aboard Lucky Lady III (serial number which was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James H. Morris, who had flown as the co-pilot aboard the Lucky Lady II when it made the world’s first non-stop circumnavigation in 1949. Heading east, one of the planes was unable to refuel successfully from a Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighter and was forced to land at Goose Bay Air Base in Labrador. The second spare refueled with the rest of the planes over Casablanca, Morocco and then split off as planned to land at RAF Brize Norton in England.

We all look for firsts in things, like first steps, first words, first man in space, first man on the moon, and in this case, the first around the world flight of a jet engine. You would expect that it might be some new jet, designed by an aviation expert, and you would be right, but the flight in question happened on January 16, 1957. The plans were three Boeing B-52 Stratofortresses. This was not just a flight for the purpose of setting a record, but rather it was a flight designed to prove a very important point. The operation was called Operation Power Flite…I’m not sure why flight was spelled flite. The planes made the trip around the world in 45 hours and 19 minutes, using in-flight refueling so that they could stay aloft for the entire journey. The mission was intended to demonstrate that the United States had the ability to drop a hydrogen bomb anywhere in the world. Led by Major General Archie J. Old, Jr. as flight commander, five B-52B aircraft of the 93rd Bombardment Wing of the 15th Air Force took off from Castle Air Force Base in California on January 16, 1957, at 1:00 PM, with two of the planes flying as spares. Old was aboard Lucky Lady III (serial number which was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James H. Morris, who had flown as the co-pilot aboard the Lucky Lady II when it made the world’s first non-stop circumnavigation in 1949. Heading east, one of the planes was unable to refuel successfully from a Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighter and was forced to land at Goose Bay Air Base in Labrador. The second spare refueled with the rest of the planes over Casablanca, Morocco and then split off as planned to land at RAF Brize Norton in England.

After a mid-air refueling rendezvous over Saudi Arabia, the planes followed the coast of India to Sri Lanka and then made a simulated bombing drop south of the Malay Peninsula before heading towards the next air refueling rendezvous over Manila and Guam. The three planes continued across the Pacific Ocean and landed at March Air Force Base near Riverside, California on January 18 after flying for a total of 45 hours and 19 minutes, with the lead plane landing at 10:19 AM and the other two planes following each other separated by  80 seconds. The 24,325 miles flight was completed at an average speed of 525 miles per hour and was completed in less than half the time required by Lucky Lady II when it made the first non-stop circumnavigation in 1949. General Curtis LeMay was among the 1,000 on hand to greet the three planes, and he awarded all 27 crew members the Distinguished Flying Cross. Though Old called the flight “a routine training mission,” the Air Force emphasized that the mission demonstrated its “capability to drop a hydrogen bomb anywhere in the world.” The flight was in reality, a warning to hostile nations, that the United States was capable of dropping a bomb anywhere in the world, and it would be for the best if these nations did not provoke the United States.

80 seconds. The 24,325 miles flight was completed at an average speed of 525 miles per hour and was completed in less than half the time required by Lucky Lady II when it made the first non-stop circumnavigation in 1949. General Curtis LeMay was among the 1,000 on hand to greet the three planes, and he awarded all 27 crew members the Distinguished Flying Cross. Though Old called the flight “a routine training mission,” the Air Force emphasized that the mission demonstrated its “capability to drop a hydrogen bomb anywhere in the world.” The flight was in reality, a warning to hostile nations, that the United States was capable of dropping a bomb anywhere in the world, and it would be for the best if these nations did not provoke the United States.

I grew up in Casper, Wyoming in the 70’s. There wasn’t a whole lot for the teen crowd to do, so we all rode “The Strip.” The Strip included all of CY Avenue and part of Center Street and 2nd Street. Most if the kids who had access to a car or knew someone who did, were out on the Strip every Friday and Saturday night. People would show off their “ride,” if they had a cool one, and meet up with their friends. My husband, Bob Schulenberg and I had lots of good friends we hooked up with on the Strip. One of our good friends was Lana Alldredge. Lana had one of those “rides” that was one to show off…a 1970 Mustang Mach 1…Canary Yellow with black stripes. She was so proud of that car. Every night before heading out to ride the Strip, Lana took her car to the carwash for a bath, because she couldn’t stand the thought of her car being dirty when people saw it. Now Lana was out of high school, and so rode the Strip every night, while my parents wouldn’t let me go out on school nights. Nevertheless, lots of kids could go out every night,

I grew up in Casper, Wyoming in the 70’s. There wasn’t a whole lot for the teen crowd to do, so we all rode “The Strip.” The Strip included all of CY Avenue and part of Center Street and 2nd Street. Most if the kids who had access to a car or knew someone who did, were out on the Strip every Friday and Saturday night. People would show off their “ride,” if they had a cool one, and meet up with their friends. My husband, Bob Schulenberg and I had lots of good friends we hooked up with on the Strip. One of our good friends was Lana Alldredge. Lana had one of those “rides” that was one to show off…a 1970 Mustang Mach 1…Canary Yellow with black stripes. She was so proud of that car. Every night before heading out to ride the Strip, Lana took her car to the carwash for a bath, because she couldn’t stand the thought of her car being dirty when people saw it. Now Lana was out of high school, and so rode the Strip every night, while my parents wouldn’t let me go out on school nights. Nevertheless, lots of kids could go out every night,  so her car was one that was well known, and had the reputation of always being clean, shiny, and tricked out. If you rode the Strip, you knew Lana’s car.

so her car was one that was well known, and had the reputation of always being clean, shiny, and tricked out. If you rode the Strip, you knew Lana’s car.

I read somewhere that in Minnetonka, Minnesota, there is a law, currently on the books that would work well for Lana, but not so much for most people. According to section 845.110 of Minnetonka, Minnesota’s city laws, there are several situations that are deemed a “public nuisance”, including but certainly not limited to ” a truck or other vehicle whose wheels or tires deposit mud, dirt, sticky substances, litter or other material on any street or highway“. Now, if you ask me, that is extreme. The only way to never have dirty tires is pretty much to bathe your vehicle constantly. While someone like Lana would be ok with that in her Mach 1 years, most people can’t see the point in a daily car bath, just so they didn’t get dirt on the street…in fact, the law is simply, outrageously insane, if you ask me.

I agree with city beautification, and I can see not wanting the citizens throw shovel loads of dirt or mud onto the city streets, but lets face it…the wind probably deposits more, dirt and litter that the car tires do. Dirty tires, seem more like a relatively unavoidable consequence, rather than considering it a public nuisance, which is defined as something that disturbs peace, safety, and/or general welfare. Dirty tires are a little bit of a stretch here. On the other hand, there really aren’t many things that are less appealing than a dirty truck, especially when it has dirty tires, so maybe this law was founded on some good principles. Still, if this is a law that is still enforced, I don’t think I would want to live in Minnetonka, Minnesota.

I agree with city beautification, and I can see not wanting the citizens throw shovel loads of dirt or mud onto the city streets, but lets face it…the wind probably deposits more, dirt and litter that the car tires do. Dirty tires, seem more like a relatively unavoidable consequence, rather than considering it a public nuisance, which is defined as something that disturbs peace, safety, and/or general welfare. Dirty tires are a little bit of a stretch here. On the other hand, there really aren’t many things that are less appealing than a dirty truck, especially when it has dirty tires, so maybe this law was founded on some good principles. Still, if this is a law that is still enforced, I don’t think I would want to live in Minnetonka, Minnesota.

January 13, 1982 found Washington DC in the middle of a severe snowstorm. The Washington National Airport was closed due to heavy snowfall…in excess of 6.5 inches. The airport reopened at noon under barely marginal conditions, but decreasing snow. The planes that had been waiting, began the de-icing process, including an Air Florida Boeing 727. The plane had flown into Washington from Miami in the early afternoon and was supposed to return to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, after a short stop. The short layover turned into a much longer one when the airport closed. When it reopened, the plane was de-iced with chemical anti-freeze, but the planes still had difficulty moving away from the gate due to the ice, so when it eventually made it to the airport’s only usable runway, it was forced to wait 45 minutes more for clearance to take off.

January 13, 1982 found Washington DC in the middle of a severe snowstorm. The Washington National Airport was closed due to heavy snowfall…in excess of 6.5 inches. The airport reopened at noon under barely marginal conditions, but decreasing snow. The planes that had been waiting, began the de-icing process, including an Air Florida Boeing 727. The plane had flown into Washington from Miami in the early afternoon and was supposed to return to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, after a short stop. The short layover turned into a much longer one when the airport closed. When it reopened, the plane was de-iced with chemical anti-freeze, but the planes still had difficulty moving away from the gate due to the ice, so when it eventually made it to the airport’s only usable runway, it was forced to wait 45 minutes more for clearance to take off.

Not wanting to further delay the flight, the pilot, Larry Wheaton, did not return to the terminal for more de-icing, and worse, failed to turn on the plane’s own de-icing system. In fact, the pilot and co-pilot actually discussed the situation, and the co-pilot said “It’s a losing battle trying to de-ice these things. It gives you a false sense of security, that’s all it does.” During the delay, however, ice was accumulating on the wings, and  by the time the plane reached the end of the runway, it was able to achieve only a few hundred feet of altitude.

by the time the plane reached the end of the runway, it was able to achieve only a few hundred feet of altitude.

The Air Florida flight took off from Washington National Airport in Arlington, Virginia, with 74 passengers and 5 crew members on board. Thirty seconds later, the plane crashed into the 14th Street Bridge over the Potomac River, less than a mile away from the runway. Seven vehicles traveling on the bridge were struck by the 727 and the plane fell into the freezing water. It was later determined that 73 of the people on board the plane died from the impact, leaving only six survivors in the river. In addition, four motorists, who had been on the bridge, died in the crash. Terrible traffic in Washington that day made it almost impossible for rescue workers to reach the scene. Witnesses didn’t know what to do to assist the survivors who were stuck in the freezing river. Finally, a police helicopter arrived and began assisting the survivors in a very risky operation.

Two people in particular emerged as heroes during the rescue…Arland Williams and Lenny Skutnik. Known as  the “sixth passenger,” Williams survived the crash, and passed lifelines on to others rather than take one for himself. He ended up being the only plane passenger to die from drowning. When one of the survivors to whom Williams had passed a lifeline was unable to hold on to it, Skutnik, who was watching the unfolding tragedy, jumped into the water and swam to rescue her. Both Skutnik and Williams, along with bystander Roger Olian, received the Coast Guard Gold Lifesaving Medal. The bridge was later renamed the Arland D. Williams Jr. Memorial Bridge. It was a completely preventable tragedy, and all because they got in a hurry.

the “sixth passenger,” Williams survived the crash, and passed lifelines on to others rather than take one for himself. He ended up being the only plane passenger to die from drowning. When one of the survivors to whom Williams had passed a lifeline was unable to hold on to it, Skutnik, who was watching the unfolding tragedy, jumped into the water and swam to rescue her. Both Skutnik and Williams, along with bystander Roger Olian, received the Coast Guard Gold Lifesaving Medal. The bridge was later renamed the Arland D. Williams Jr. Memorial Bridge. It was a completely preventable tragedy, and all because they got in a hurry.

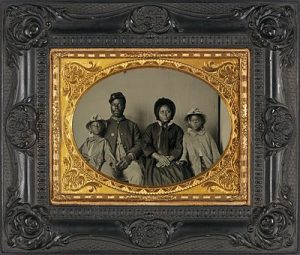

The Ambrotype (from the Ancient Greek words for immortal or impression) or Amphitype, also known as a collodion positive in England, is a positive photograph on glass made by a variant of the wet plate collodion process. Like a print on paper, it is viewed by reflected light. Like the Daguerreotype, which it replaced, and like the prints produced by a Polaroid camera, each is a unique original that could only be duplicated by using a camera to copy it.

The Ambrotype (from the Ancient Greek words for immortal or impression) or Amphitype, also known as a collodion positive in England, is a positive photograph on glass made by a variant of the wet plate collodion process. Like a print on paper, it is viewed by reflected light. Like the Daguerreotype, which it replaced, and like the prints produced by a Polaroid camera, each is a unique original that could only be duplicated by using a camera to copy it.

The Ambrotype was introduced in the 1850s. Then, during the 1860s it was replaced by the tintype, a similar photograph on thin black-lacquered iron, hard to distinguish from an Ambrotype, if under glass. It is quite the process. One side of a clean glass plate was coated with a thin layer of iodized collodion; which is a flammable, syrupy solution of pyroxylin (also known as “nitrocellulose,” “cellulose nitrate,” “flash paper,” and “gun cotton”) in ether and alcohol. The glass is then dipped in a silver nitrate solution. The plate was exposed in the camera while still wet. Exposure times varied from five to sixty seconds or more depending on the brightness of the lighting and the speed of the camera lens. The plate was then developed and fixed. The resulting negative, when viewed by reflected light against a black background, appears to be a positive image: the clear areas look black, and the exposed, opaque areas appear relatively light. This effect was integrated by backing the plate with black velvet; by taking the  picture on a plate made of dark reddish-colored glass (the result was called a ruby Ambrotype); or by coating one side of the plate with black varnish. Either the emulsion side or the bare side could be coated: if the bare side was blackened, the thickness of the glass added a sense of depth to the image. In either case, another plate of glass was put over the fragile emulsion side to protect it, and the whole was mounted in a metal frame and kept in a protective case. In some instances the protective glass was cemented directly to the emulsion, generally with a balsam resin. This protected the image well but tended to darken it. Ambrotypes were sometimes hand-tinted; untinted ambrotypes are monochrome, gray or tan in their lightest areas.

picture on a plate made of dark reddish-colored glass (the result was called a ruby Ambrotype); or by coating one side of the plate with black varnish. Either the emulsion side or the bare side could be coated: if the bare side was blackened, the thickness of the glass added a sense of depth to the image. In either case, another plate of glass was put over the fragile emulsion side to protect it, and the whole was mounted in a metal frame and kept in a protective case. In some instances the protective glass was cemented directly to the emulsion, generally with a balsam resin. This protected the image well but tended to darken it. Ambrotypes were sometimes hand-tinted; untinted ambrotypes are monochrome, gray or tan in their lightest areas.

The Ambrotype was based on the wet plate collodion process invented by Frederick Scott Archer. Ambrotypes were deliberately underexposed negatives made by that process and optimized for viewing as positives instead. In the United States, ambrotypes first came into use in the early 1850s. In 1854, James Ambrose Cutting of  Boston took out several patents relating to the process. He may be responsible for coining the term “Ambrotype.” Ambrotypes were much less expensive to produce than daguerreotypes, the medium that predominated when they were introduced, and did not have the bright mirror-like metallic surface that could make daguerreotypes troublesome to view and which some people disliked. An Ambrotype, however, appeared dull and drab when compared with the brilliance of a well-made and properly viewed daguerreotype. It’s amazing to me that photography could be so complicated…especially when you think that these days, everything is digital, and errors can easily be fixed with Photoshop.

Boston took out several patents relating to the process. He may be responsible for coining the term “Ambrotype.” Ambrotypes were much less expensive to produce than daguerreotypes, the medium that predominated when they were introduced, and did not have the bright mirror-like metallic surface that could make daguerreotypes troublesome to view and which some people disliked. An Ambrotype, however, appeared dull and drab when compared with the brilliance of a well-made and properly viewed daguerreotype. It’s amazing to me that photography could be so complicated…especially when you think that these days, everything is digital, and errors can easily be fixed with Photoshop.

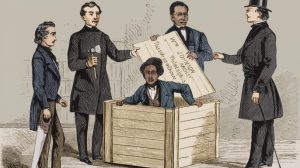

There are times when what you know is what gets you through a bad situation, but there are some situations that really do requiring knowing someone who can help. For the slaves in the pre-emancipation era of the United States, that was as true as it gets. The slaves had none of the most important asset needed for escape…money. That didn’t stop the attempts. One slave who was from the deeper south, Henry “Box” Brown, decided to mail himself to safety. That did work, but not everyone had the ability to get that done, and so the majority just decided to make a run for it…only to be met by dogs or Bounty Hunters…neither was going to have a good outcome.

There are times when what you know is what gets you through a bad situation, but there are some situations that really do requiring knowing someone who can help. For the slaves in the pre-emancipation era of the United States, that was as true as it gets. The slaves had none of the most important asset needed for escape…money. That didn’t stop the attempts. One slave who was from the deeper south, Henry “Box” Brown, decided to mail himself to safety. That did work, but not everyone had the ability to get that done, and so the majority just decided to make a run for it…only to be met by dogs or Bounty Hunters…neither was going to have a good outcome.

One rather famous slave named Mustapha, teamed up with a white hunchback named Arthur Howe and conned his way to freedom. It was probably the most outrageous, and yet the best planned escape there was. The plan was simple, the pair traveled through North Carolina and Virginia, telling anyone they met that Mustapha was Howe’s slave. Since Howe was famous for his fearsome appearance and “expressive of dark angry passions,” that few people dared to ask any more questions. Whenever Howe and Mustapha, reached a town, Howe would sell Mustapha for a tidy fee. After a few days recuperating, Mustapha would escape again and the partners would resume their journey. Not only did this help avoid bounty hunters, who would be looking for an escaped slave, rather than a current one, it brought in a tidy profit as well. Mustapha was quite a brave man. He was not worried that he would not be able to escape the people he was sold too. Most slaves struggled to escape once…Mustapha did it every week.  He also had to trust Howe to continue to be there waiting for him so they could continue their journey.

He also had to trust Howe to continue to be there waiting for him so they could continue their journey.

The plan worked perfectly and as planned the pair parted ways, after reaching Petersburg or Richmond. This put Mustapha free to make his escape north. Since he was not apprehended, it is believed that this was what happened. No one is exactly positive about that, but the duo dropped out of history after that, so it is believed to be the way everything went down. When we look back on the many deaths that followed an escape attempt, I have to think that it is sad that more slaves didn’t think of this idea. I’m sure the many slave owners who were scammed though, I think there was a little justice in the world after all.

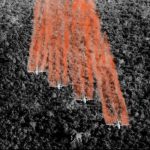

The Vietnam war was many things, but I don’t think anyone really expected Operation Ranch Hand…at least not the general public. Who would have expected such a heinous act to be carried out by the government. Operation Ranch Hand was a United States military operation during the Vietnam War, lasting from 1962 until 1971. The operation was largely inspired by the British use of 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D (Agent Orange) during the Malayan Emergency in the 1950s. It was part of the overall program during the war called “Operation Trail Dust.” Ranch Hand involved spraying an estimated 20 million United States gallons of defoliants and herbicides over rural areas of South Vietnam in an attempt to deprive the Viet Cong of food and vegetation cover. Nearly 20,000 sorties were flown between 1961 and 1971.

The Vietnam war was many things, but I don’t think anyone really expected Operation Ranch Hand…at least not the general public. Who would have expected such a heinous act to be carried out by the government. Operation Ranch Hand was a United States military operation during the Vietnam War, lasting from 1962 until 1971. The operation was largely inspired by the British use of 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D (Agent Orange) during the Malayan Emergency in the 1950s. It was part of the overall program during the war called “Operation Trail Dust.” Ranch Hand involved spraying an estimated 20 million United States gallons of defoliants and herbicides over rural areas of South Vietnam in an attempt to deprive the Viet Cong of food and vegetation cover. Nearly 20,000 sorties were flown between 1961 and 1971.

It’s hard to say if the government knew the consequences of the chemicals that were used. It’s possible that the chemicals were thought to just kill vegetation, and not to hurt people. The people involved were known as  Ranch Handers. I seriously doubt that at some point they didn’t wonder if what they were doing could possibly be harmful to the people they were spraying it on or near. Nevertheless, the “Ranch Handers” had a motto, “Only you can prevent a forest.” It was a take on the popular United States Forest Service poster slogan of Smokey Bear. During the ten years of spraying, over 5 million acres of forest and 500,000 acres of crops were heavily damaged or destroyed. Around 20% of the forests of South Vietnam were sprayed at least once.

Ranch Handers. I seriously doubt that at some point they didn’t wonder if what they were doing could possibly be harmful to the people they were spraying it on or near. Nevertheless, the “Ranch Handers” had a motto, “Only you can prevent a forest.” It was a take on the popular United States Forest Service poster slogan of Smokey Bear. During the ten years of spraying, over 5 million acres of forest and 500,000 acres of crops were heavily damaged or destroyed. Around 20% of the forests of South Vietnam were sprayed at least once.

The herbicides were sprayed by the United States Air Force flying C-123s using the call sign “Hades.” The planes were fitted with specially developed spray tanks with a capacity of 1,000 United States gallons of herbicides. A plane sprayed a swath of land that was ½ mile wide and 10 miles long in about 4½ minutes, at a rate of about 3 United States gallons per acre. Sorties usually consisted of three to five airplanes flying side by  side, and 95% of the herbicides and defoliants used in the war were sprayed by the United States Air Force as part of Operation Ranch Hand. The remaining 5% were sprayed by the United States Chemical Corps, other military branches, and the Republic of Vietnam using hand sprayers, spray trucks, helicopters and boats, primarily around United States military installations…meaning that the majority of the chemicals were exposed to the Untied States Military. Many of the Vietnam veterans have felt betrayed by their own government. Many have felt that the government was well aware of the dangers of the chemicals they were spraying. I don’t know if they knew or not, but it seems like they should have suspected something. Years later, the effects of Agent Orange are well known and it was vicious.

side, and 95% of the herbicides and defoliants used in the war were sprayed by the United States Air Force as part of Operation Ranch Hand. The remaining 5% were sprayed by the United States Chemical Corps, other military branches, and the Republic of Vietnam using hand sprayers, spray trucks, helicopters and boats, primarily around United States military installations…meaning that the majority of the chemicals were exposed to the Untied States Military. Many of the Vietnam veterans have felt betrayed by their own government. Many have felt that the government was well aware of the dangers of the chemicals they were spraying. I don’t know if they knew or not, but it seems like they should have suspected something. Years later, the effects of Agent Orange are well known and it was vicious.

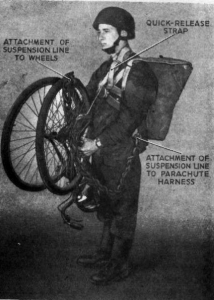

When we think about war machines, we think of planes, tanks, ships, and even horses, but we very seldom…if ever, think of bicycles. Nevertheless, bicycles were used in a number of wars, and even continue to be used to this day. The late 19th century brought several experiments into the possible role of bicycles and cycling within military establishments, primarily because they can carry more equipment and travel longer distances than walking soldiers could. The development of pneumatic tires coupled with shorter, sturdier frames in the late 19th century led military establishments to investigate the possibility of bicycles in combat. To some extent, bicyclists took over the functions of dragoons, especially as messengers and scouts, substituting for horses in warfare. Bicycle units or detachments were in existence by the end of the 19th century in most armies.

When we think about war machines, we think of planes, tanks, ships, and even horses, but we very seldom…if ever, think of bicycles. Nevertheless, bicycles were used in a number of wars, and even continue to be used to this day. The late 19th century brought several experiments into the possible role of bicycles and cycling within military establishments, primarily because they can carry more equipment and travel longer distances than walking soldiers could. The development of pneumatic tires coupled with shorter, sturdier frames in the late 19th century led military establishments to investigate the possibility of bicycles in combat. To some extent, bicyclists took over the functions of dragoons, especially as messengers and scouts, substituting for horses in warfare. Bicycle units or detachments were in existence by the end of the 19th century in most armies.

By World War I, the level terrain in Belgian was well used by military cyclists, prior to the onset of trench  warfare. Each of the four Belgian carabinier battalions included a company of cyclists, equipped with a brand of folding, portable bicycle named the Belgica. A regimental cyclist school gave training in map reading, reconnaissance, reporting, and the carrying of verbal messages. Attention was paid to the maintenance and repair of the machine itself. The bicycle could be used to ride when it was feasible, and carried when the pat was not suitable to riding. The bicycle made no noise, so unless the trail was littered with twigs, the bicycle make very little noise. Sneaking up on the enemy was possible.

warfare. Each of the four Belgian carabinier battalions included a company of cyclists, equipped with a brand of folding, portable bicycle named the Belgica. A regimental cyclist school gave training in map reading, reconnaissance, reporting, and the carrying of verbal messages. Attention was paid to the maintenance and repair of the machine itself. The bicycle could be used to ride when it was feasible, and carried when the pat was not suitable to riding. The bicycle made no noise, so unless the trail was littered with twigs, the bicycle make very little noise. Sneaking up on the enemy was possible.

In the United States, the most extensive experimentation on bicycle units was carried out by 1st Lieutenant Moss, of the 25th United States Infantry (Colored), which was made up of African American infantry soldiers with European American officers. Using a variety of cycle models, Moss and his troops carried out extensive bicycle journeys covering between 800 and 1,900 miles. Late in the 19th century, the United States Army tested the bicycle’s suitability for cross-country troop transport. Buffalo Soldiers stationed in Montana rode bicycles across roadless landscapes for hundreds of miles at high speed. The “wheelmen” traveled the 1,900 Miles to Saint Louis, Missouri in 34 days with an average speed of over 6 miles per hour. The bicycles were even used in the paratrooper deployment. These bicycles not only folded up, but they were equipped with an on board rifle. I don’t know how hard it was to handle a gun while riding a bike, but I’m sure it was a relief to have your gun right there.

The first known use of the bicycle in combat occurred during the Jameson Raid, in which cyclists carried messages. In the Second Boer War, military cyclists were used primarily as scouts and messengers. One unit  patrolled railroad lines on specially constructed tandem bicycles that were fixed to the rails. Several raids were conducted by cycle-mounted infantry on both sides; the most famous unit was the Theron se Verkenningskorps (Theron Reconnaissance Corps) or TVK, a Boer unit led by the scout Daniel Theron, whom British commander Lord Roberts described as “the hardest thorn in the flesh of the British advance.” Roberts placed a reward of £1,000 on Theron’s head…dead or alive…and dispatched 4,000 soldiers to find and eliminate the TVK. While scouting alone on a road near Gatsrand, about 3.7 miles north of present-day Fochville, he encountered seven members of Marshall’s Horse and was killed in action.

patrolled railroad lines on specially constructed tandem bicycles that were fixed to the rails. Several raids were conducted by cycle-mounted infantry on both sides; the most famous unit was the Theron se Verkenningskorps (Theron Reconnaissance Corps) or TVK, a Boer unit led by the scout Daniel Theron, whom British commander Lord Roberts described as “the hardest thorn in the flesh of the British advance.” Roberts placed a reward of £1,000 on Theron’s head…dead or alive…and dispatched 4,000 soldiers to find and eliminate the TVK. While scouting alone on a road near Gatsrand, about 3.7 miles north of present-day Fochville, he encountered seven members of Marshall’s Horse and was killed in action.

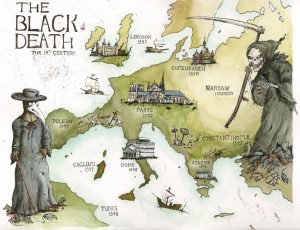

Sometimes, people can associate certain things with certain religions, and even Satanism. They can then make decisions on life based on what they perceive something to be. Unfortunately, sometimes those decisions end up being disastrous. Such was the case with Pope George IX, who decided that cats where a part of devil worship, and so ruled that cats should be exterminated. Cats throughout Europe were exterminated in droves immediately thereafter. Of course, we know that while some religions might use certain animals in their religious practices, that does not make the animal evil…but rather, the animal is a victim of that religion, much like people in certain religions use snakes as a part of worship.

Sometimes, people can associate certain things with certain religions, and even Satanism. They can then make decisions on life based on what they perceive something to be. Unfortunately, sometimes those decisions end up being disastrous. Such was the case with Pope George IX, who decided that cats where a part of devil worship, and so ruled that cats should be exterminated. Cats throughout Europe were exterminated in droves immediately thereafter. Of course, we know that while some religions might use certain animals in their religious practices, that does not make the animal evil…but rather, the animal is a victim of that religion, much like people in certain religions use snakes as a part of worship.

After the cats were removed from Europe, an unexpected and horrific side effect occurred. The sudden lack of cats led to the spread of disease because infected rats ran free. The most devastating of these diseases, the Bubonic Plague, killed 100 million people. Pope Gregory lived from 1145 to 1241, AD, so little was known about how disease was passed. He was born Ugolino di Conti but took the name Gregory when he became the pope. That was when Ugolino was over 80 years old, not a young age to take on the papal role.

The cat fiasco is just one part of Pope Gregory IX’s story. He is mostly known for issuing the Decretals and starting the Papal Inquisition. The Decretals reorganized the whole library of Catholic laws. The papal inquisition rained down justice on heretics, the people who spoke out against the church. It was Gregory’s past  as a lawyer that connected him to his acts of justice within the church. It was his distaste for cats that penned the Vox in Rama (the papal decree – this one about the cats). That was the first church document condemning black cats as instruments of satan. By Gregory’s decree, there was a target on the head of every black cat. The Black Death or Black Plague was the original zombie apocalypse. People living during this time lived in constant fear of death. Many believed this was the end of the human race, and that is understandable. It was one of the most deadly pandemics in history. By rough estimates, as many as 200 million people died. If you survived, you lost many loved ones, and in Europe, it was all because of a lack of cats.

as a lawyer that connected him to his acts of justice within the church. It was his distaste for cats that penned the Vox in Rama (the papal decree – this one about the cats). That was the first church document condemning black cats as instruments of satan. By Gregory’s decree, there was a target on the head of every black cat. The Black Death or Black Plague was the original zombie apocalypse. People living during this time lived in constant fear of death. Many believed this was the end of the human race, and that is understandable. It was one of the most deadly pandemics in history. By rough estimates, as many as 200 million people died. If you survived, you lost many loved ones, and in Europe, it was all because of a lack of cats.