History

Most often, when we think of the early Americans, and their settlements, we think about the settlers who came over from Europe, but there were, of course, the many Indian tribes that existed here first. I’m not going to dispute whether the Indians or the White Man have more right to be here, because I truly believe that we should all be able to co-exist here after all these years, and that while treaties were broken many times, we have more than likely paid for this land a number of times, given the money that has been, and continues to be paid to the Native Americans. The oldest known culture in the United States was the Pueblo Indians, who lived in the Southwestern United States. Their name is Spanish for “stone masonry village dweller.” They are believed to be the descendants of three major cultures…the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Ancient Puebloans (Anasazi) Indians. I’m not sure how they would have come to be here, unless their ancestors were here first, but that is how the historians see it.

Most often, when we think of the early Americans, and their settlements, we think about the settlers who came over from Europe, but there were, of course, the many Indian tribes that existed here first. I’m not going to dispute whether the Indians or the White Man have more right to be here, because I truly believe that we should all be able to co-exist here after all these years, and that while treaties were broken many times, we have more than likely paid for this land a number of times, given the money that has been, and continues to be paid to the Native Americans. The oldest known culture in the United States was the Pueblo Indians, who lived in the Southwestern United States. Their name is Spanish for “stone masonry village dweller.” They are believed to be the descendants of three major cultures…the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Ancient Puebloans (Anasazi) Indians. I’m not sure how they would have come to be here, unless their ancestors were here first, but that is how the historians see it.

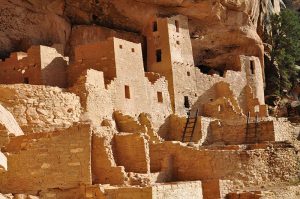

Over the years, the Ancient Puebloans, who had been a nomadic, hunter-gathering society, evolved into a sedentary culture. They made their homes in the Four Corners region of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Arizona. The Puebloans continued to hunt, but they also expanded to agriculture. They grew maze, corn, squash, and beans. They also raised turkeys and even developed a fairly complex irrigation system. They took up basket weaving and pottery, and became quite skilled in both. About this time, they began building the  buildings we think about when we think of the Pueblo Indians…villages, often on top of high mesas or in hollowed-out natural caves at the base of canyons. These multiple-room dwellings and apartment like complexes, designed with stone or adobe masonry, were the forerunner of the later pueblos.

buildings we think about when we think of the Pueblo Indians…villages, often on top of high mesas or in hollowed-out natural caves at the base of canyons. These multiple-room dwellings and apartment like complexes, designed with stone or adobe masonry, were the forerunner of the later pueblos.

Sadly, even with their successful life changes, the Ancient Puebloans way of life declined in the 1300’s, probably due to drought and inter-tribal warfare. They migrated south, primarily into New Mexico and Arizona, becoming what is today known as the Pueblo people. For hundreds of years, these Pueblo descendants lived a similar lifestyle to their ancestors. They continued to survive by hunting and farming, and also building “new” apartment-like structures, sometimes several stories high. These new structures were made of cut sandstone faced with adobe, which is a combination of earth mixed with straw and water. Sometimes, the adobe was poured into forms or made into sun-dried bricks to build walls that are often several feet thick. The buildings had flat roofs, which served as working or resting places, as well as observation points to watch for approaching enemies and view ceremonial occasions. For better defense, the outer walls generally had no doors or windows, but instead, window openings in the roofs, with ladders leading into the interior.

Each family unit consisted of a single room of the building unless the family grew too large. Then side-rooms were sometimes added. The houses of the pueblo were usually built around a central, open space or plaza in the middle of which was a “kiva,” a sunken chamber used for religious purposes. Each pueblo was an independent and separate community. The different pueblos shared similarities in language and customs, but each pueblo had its own chief, and sometimes two chiefs, a summer and winter chief, who alternated. Most important affairs, such was war, hunting, religion, and agriculture, however, were governed by priesthoods or secret societies. Each pueblo was almost a separate country.

Each family unit consisted of a single room of the building unless the family grew too large. Then side-rooms were sometimes added. The houses of the pueblo were usually built around a central, open space or plaza in the middle of which was a “kiva,” a sunken chamber used for religious purposes. Each pueblo was an independent and separate community. The different pueblos shared similarities in language and customs, but each pueblo had its own chief, and sometimes two chiefs, a summer and winter chief, who alternated. Most important affairs, such was war, hunting, religion, and agriculture, however, were governed by priesthoods or secret societies. Each pueblo was almost a separate country.

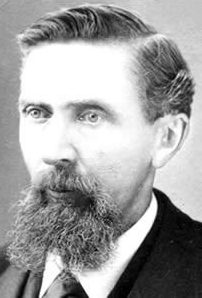

The term “coward” doesn’t normally bring with it thoughts of bravery in the face of danger, but perhaps it should…sometimes anyway. Charles Joseph Coward was born in Britain on January 30, 1905. I can’t say what his young life was like, and perhaps it was his parents who taught him to prove his name wrong, but I’m quite sure they were proud of just how well he proved that he was anything, but a coward. Coward joined the British Army in 1937 and served with the 8th Reserve Regimental Royal Artillery. By the time WWII started in 1939, he was a Quartermaster Battery Sergeant Major. They already saw something in him that disproved his name.

The term “coward” doesn’t normally bring with it thoughts of bravery in the face of danger, but perhaps it should…sometimes anyway. Charles Joseph Coward was born in Britain on January 30, 1905. I can’t say what his young life was like, and perhaps it was his parents who taught him to prove his name wrong, but I’m quite sure they were proud of just how well he proved that he was anything, but a coward. Coward joined the British Army in 1937 and served with the 8th Reserve Regimental Royal Artillery. By the time WWII started in 1939, he was a Quartermaster Battery Sergeant Major. They already saw something in him that disproved his name.

In World War II, Coward was fighting against the Nazis when the Germans assaulted the port of Calais on May 21, 1940, marking the start of the Siege of Calais. The German army drove the Allies back, and the British Expeditionary Force fled from France through the port of Dunkirk. Fortunately, most made it out in time…to fight the Germans another day. Unfortunately for Coward, he was not one of them, and he became a POW. He did have an advantage, however, in that he spoke German. He used his language skills to make seven escape attempts by passing himself off as a German soldier. One of the escape attempts worked. He was free, but he was injured, and was sent to a German Army field hospital. Coward kept up his German soldier act. After the German doctors had treated his wounds, he was awarded an Iron Cross for his bravery and suffering. Unfortunately, they realized their mistake pretty quickly. Coward was sent back to the POW camp where he earned a reputation for sabotage while on work details. Finally, he was sent to Poland…Auschwitz, to be precise…not to the death camp part of Auschwitz, but rather to the work camp part of it. Coward arrived at Auschwitz III (Monowitz), which was the working camp, in December 1943. The camp was located approximately five miles from Auschwitz II (Birkenau), which was the death camp. There he became a modern day “Hogan’s Hero,” although there was nothing funny about his situation, like there was in the television show. Coward spied on his captors and risked his life to save those he could. All that under the name of Coward.

IG Farben was a German chemical and pharmaceutical industry conglomerate. Its name was taken from Interessen-Gemeinschaft Farbenindustrie. IG Farben had acquired the patent to Zyklon B. It was originally used as an insecticide and by US immigration officials to delouse Mexican laborers. The Nazis had a different use for it…the extermination of Jews and other undesirables. Coward and between 1,200 and 1,400 other British POWs were kept at sub-camp E715. Their job was to run the liquid fuel plant which produced synthetic rubber. Coward, due to his German language skills worked as a Red Cross liaison officer, because Germany was still keeping up the pretense of honoring the Geneva Convention articles. He was allowed some measure of free movement within the camp, and even permitted to go to the nearby towns. In town, Coward saw trainloads of Jews arriving at the the extermination camp. Auschwitz III housed 10,000 Jews who were “allowed” to work. They were worked to the point of exhaustion and sickness. Given the brutality and deliberate starvation they did not last long. Coward simply couldn’t stand by and do nothing. The British POWs had access to Red Cross items, so Coward and the other prisoners set aside food and medicine to be smuggled to the Jewish section of their camp, to help as many as possible. Coward was allowed to send letters out, so he began writing to his friend…Mr. William Orange, a fictitious person. It was actually the code for the British War Office. In those letters, he explained what was happening in the camps, as well as the treatment and mass slaughter of Jews. One day, a letter was smuggled to him, asking for help. It came from Karel Sperber, a British ship’s doctor, but there was a problem…Sperber was being held in the Jewish section of Monowitz. So Coward exchanged clothes with an inmate and smuggled himself into the Jewish sector to try to find the doctor. Sadly, he failed, but he did see how Jews in the work camp were being treated. After the war, he was among those who testified at the IG Farben Trial in Nuremberg. He helped to have some of the company’s directors imprisoned, although only for a few years.

He wanted to help the Jews, but to pull it off, he needed two things…chocolate and corpses. It was a daring plan, but it worked. Coward gave the chocolate to the guards in exchange for the bodies of non-Jewish dead prisoners. Then, once their clothes and papers had been removed they were cremated. Jewish escapees put on the clothes and assumed the new, non-Jewish identities. With help from members of the Polish resistance, they were then smuggled out of the camp. As the number of those missing tallied with the number of those who were reported dead, neither Coward nor the bribed guards fell under any suspicion. It is estimated around 400

Jews were saved using Coward’s method. In January 1945 Soviet forces advanced deeper into Poland. As they made their way toward Auschwitz, Coward and the other POWs were forced to march to Bavaria in Germany. The prisoners were liberated by Allied forces en route, finally putting an end to the brutal nightmare. In 1963 Yad Vashem recognized Coward as one of the Righteous Among the Nations. He became known as the “Count of Auschwitz.” and a film was made of his exploits called “The Password is Courage.” I think he was a pretty brave man…for a Coward.

Jews were saved using Coward’s method. In January 1945 Soviet forces advanced deeper into Poland. As they made their way toward Auschwitz, Coward and the other POWs were forced to march to Bavaria in Germany. The prisoners were liberated by Allied forces en route, finally putting an end to the brutal nightmare. In 1963 Yad Vashem recognized Coward as one of the Righteous Among the Nations. He became known as the “Count of Auschwitz.” and a film was made of his exploits called “The Password is Courage.” I think he was a pretty brave man…for a Coward.

In March or 1941, the United States was largely considered neutral, so we could provide the countries, who were fighting Adolf Hitler, with war material. It was during this period of time, that the United Kingdom, an old enemy of the United States, since the United States fought against them for our independence, needed our help. Of course, we were allies by that time, and so the thought of a loan to the UK was not out o the question. The UK had been fighting against Adolf Hitler’s Germany army for a while by then, and funds were dwindling. The US loaned $4.33 billion to Britain in 1945, while Canada loaned US$1.19 billion in 1946, at a rate of 2% annual interest. It was a good deal, but in the end, the amount paid back was nearly double the amounts loaned in 1945 and 1946.

In March or 1941, the United States was largely considered neutral, so we could provide the countries, who were fighting Adolf Hitler, with war material. It was during this period of time, that the United Kingdom, an old enemy of the United States, since the United States fought against them for our independence, needed our help. Of course, we were allies by that time, and so the thought of a loan to the UK was not out o the question. The UK had been fighting against Adolf Hitler’s Germany army for a while by then, and funds were dwindling. The US loaned $4.33 billion to Britain in 1945, while Canada loaned US$1.19 billion in 1946, at a rate of 2% annual interest. It was a good deal, but in the end, the amount paid back was nearly double the amounts loaned in 1945 and 1946.

The United States was pulled into World War II shortly after, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. That marked to end of the program to provide military materials, because the United States was no longer considered neutral. At this point, the United States was very much needed in a very different way, and could not be neutral and be an effective help, but they also had a score to settle, and it could not be handled on the sidelines. The United States had hoped to sit this one out, but that was not to be. The Axis of Evil was winning against the Allied Nations, and they needed help, but it was the boldness of the attack on Pearl Harbor that finally awoke the sleeping giant that was the United States. The United States victory over Japan in the Battle of Midway was the turning point of the war in the Pacific. Then Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union defeated Germany at Stalingrad, marking the turning point of the war in Eastern Europe. As we all know, in the end the Allies were victorious in World War II.

There are still World War I debts owed to and by Britain. Since a moratorium on all debts from that conflict was agreed at the height of the Great Depression, no repayments have been made to or received from other nations since 1934. Despite the favorable rates there were six years in which Britain deferred payment because of economic or political crises. Britain settled its World War II debts to the United States and Canada when it paid the final  two installments in 2006. The payments of $83.25 million to the US and US$22.7 million to Canada are the last of 50 installments since 1950. Upon the final payments, the UK will have paid back a total of $7.5 billion to the US and US$2 billion to Canada. “This week we finally honor in full our commitments to the United States and Canada for the support they gave us 60 years ago,” said Treasury Minister Ed Balls at the time of those final payments. “It was vital support which helped Britain defeat Nazi Germany and secure peace and prosperity in the post-war period. We honor our commitments to them now as they honored their commitments to us all those years ago,” he added.

two installments in 2006. The payments of $83.25 million to the US and US$22.7 million to Canada are the last of 50 installments since 1950. Upon the final payments, the UK will have paid back a total of $7.5 billion to the US and US$2 billion to Canada. “This week we finally honor in full our commitments to the United States and Canada for the support they gave us 60 years ago,” said Treasury Minister Ed Balls at the time of those final payments. “It was vital support which helped Britain defeat Nazi Germany and secure peace and prosperity in the post-war period. We honor our commitments to them now as they honored their commitments to us all those years ago,” he added.

During our visit to Superior, Wisconsin, my sister, Cheryl Masterson; her daughter, Liz Masterson; and I were treated a couple of wonderful tours of the area. Our cousin, Pam Wendling and her husband Mike took us down to Canal Park, where we watched the Paul R Tragurtha coming into port to pick up a load of coal…that come to Duluth by train from none other than Gillette, Wyoming, by the way. The Paul R Tragurtha is known as the “Queen of the Lakes” and is the longest vessel on the Great Lakes at 1,013 feet 6 inches. Watching that great ship come into port is amazing. It was also great to have Pam and Mike there to give us the lake and ship history. Though we had been to Canal Park before, it just never gets old.

During our visit to Superior, Wisconsin, my sister, Cheryl Masterson; her daughter, Liz Masterson; and I were treated a couple of wonderful tours of the area. Our cousin, Pam Wendling and her husband Mike took us down to Canal Park, where we watched the Paul R Tragurtha coming into port to pick up a load of coal…that come to Duluth by train from none other than Gillette, Wyoming, by the way. The Paul R Tragurtha is known as the “Queen of the Lakes” and is the longest vessel on the Great Lakes at 1,013 feet 6 inches. Watching that great ship come into port is amazing. It was also great to have Pam and Mike there to give us the lake and ship history. Though we had been to Canal Park before, it just never gets old.

Pam and Mike also took us up the North Shore of Lake Superior to Two Harbors, Minnesota, and showed us all the

sights in that area. The lighthouse there is really pretty, and we were able to get lots of pictures. There was a ship in the harbor that was loading Taconite, which is a low-grade iron ore. For a long time, when the high-grade natural iron ore was plentiful, Taconite was considered a waste rock and not used. Then, as the supply of high-grade natural ore decreased, industry began to view Taconite as a resource. Had it not been for Mike’s knowledge of all these mining, railroad, and shipping industries in the area, and in the United States, we would have seen these things, but really wouldn’t have know anything about the rich history that went along with it. It takes someone, like Mike, with a love of history to give us that.

sights in that area. The lighthouse there is really pretty, and we were able to get lots of pictures. There was a ship in the harbor that was loading Taconite, which is a low-grade iron ore. For a long time, when the high-grade natural iron ore was plentiful, Taconite was considered a waste rock and not used. Then, as the supply of high-grade natural ore decreased, industry began to view Taconite as a resource. Had it not been for Mike’s knowledge of all these mining, railroad, and shipping industries in the area, and in the United States, we would have seen these things, but really wouldn’t have know anything about the rich history that went along with it. It takes someone, like Mike, with a love of history to give us that.

Pam and Mike also do some hiking in the area, and we were shown some of the beautiful hiking trails, and the

beautiful wooded areas around the lake. The streams and waterfalls especially appealed to us. That area has so many more trees that we have in Wyoming, and all that greenery made me long to get out and wander down the trail, but we just didn’t have the time, unfortunately. Pam suggested that Bob and I consider a hiking trip to the area, we may have to try to do that. The tours were beautiful, and the time we spent with them was very special to us. I am so glad that we have reconnected with all of our cousins in the Superior/Duluth area, and all over the nation. Amazing family connections.

beautiful wooded areas around the lake. The streams and waterfalls especially appealed to us. That area has so many more trees that we have in Wyoming, and all that greenery made me long to get out and wander down the trail, but we just didn’t have the time, unfortunately. Pam suggested that Bob and I consider a hiking trip to the area, we may have to try to do that. The tours were beautiful, and the time we spent with them was very special to us. I am so glad that we have reconnected with all of our cousins in the Superior/Duluth area, and all over the nation. Amazing family connections.

When a lake, or group of lakes, are almost the size of a small sea, with all the storm possibilities that go with a body of water the size of the sea, shipwrecks and other disasters on the water are bound to occur. There is a stretch of land along the Michigan coast, known to many as the Shipwreck Coast or the Graveyard of the Great Lakes. It is an 80 mile stretch between Grand Island and Whitefish Point, and the vicious waters have sunk hundreds of ships. Edmund Fitzgerald, Cyprus, and Vienna are just a few of the vessels lost beneath the waves, where they took their crew to a watery grave…their names forever etched in maritime lore. Their wreckages lie in varying depths of Lake Superior, the largest of the Great Lakes.

When a lake, or group of lakes, are almost the size of a small sea, with all the storm possibilities that go with a body of water the size of the sea, shipwrecks and other disasters on the water are bound to occur. There is a stretch of land along the Michigan coast, known to many as the Shipwreck Coast or the Graveyard of the Great Lakes. It is an 80 mile stretch between Grand Island and Whitefish Point, and the vicious waters have sunk hundreds of ships. Edmund Fitzgerald, Cyprus, and Vienna are just a few of the vessels lost beneath the waves, where they took their crew to a watery grave…their names forever etched in maritime lore. Their wreckages lie in varying depths of Lake Superior, the largest of the Great Lakes.

My husband, Bob and I came up for a visit in 1975, and my Uncle Bill Spencer, the original family historian, told us about the shipwrecks of Lake Superior, and how there were many that could be seen pretty clearly when flying over the lake. I wished we could have taken such a flight, and seen those ships for myself. My thoughts drifted to the time of the wrecks, and how the accident happened and about the people who lost their lives there.

My husband, Bob and I came up for a visit in 1975, and my Uncle Bill Spencer, the original family historian, told us about the shipwrecks of Lake Superior, and how there were many that could be seen pretty clearly when flying over the lake. I wished we could have taken such a flight, and seen those ships for myself. My thoughts drifted to the time of the wrecks, and how the accident happened and about the people who lost their lives there.

Lake Superior was known for its big storms, and when the November gales came it was treacherous, especially along the Shipwreck Coast. “This part of Lake Superior is particularly treacherous thanks to a unique combination of geography and storm patterns,” Bruce Lynn, executive director of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Paradise, Michigan says. “Storms build up over Canada and the Great Plains. Their strong winds blow uninterrupted over 200 miles of open waters, building up enormous waves that drive ships into the coast or break them in half.” Fog, snow squalls, smoke from forest fires, traffic jams on the busy waters and human error add to sailing hazards.

One massive ore carrier, the Edmund Fitzgerald was the largest to sail Lake Superior, nevertheless, it was a gale or a rogue wave that caused its sinking, but what it was is debated to this day. Gordon Lightfoot immortalized the tragedy in his song “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” The Fitzgerald’s 200 pound bronze bell was salvaged from the bottom of the lake later on, and and restored. The men were never recovered, because as most people know, Lake Superior never gives up her dead. The ship darted out on November 7, 1975, hoping to make Whitefish Point, but that was not to be. I think that just the questions behind the shipwrecks on Lake Superior makes the thousands of shipwrecks a huge mystery.

One massive ore carrier, the Edmund Fitzgerald was the largest to sail Lake Superior, nevertheless, it was a gale or a rogue wave that caused its sinking, but what it was is debated to this day. Gordon Lightfoot immortalized the tragedy in his song “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” The Fitzgerald’s 200 pound bronze bell was salvaged from the bottom of the lake later on, and and restored. The men were never recovered, because as most people know, Lake Superior never gives up her dead. The ship darted out on November 7, 1975, hoping to make Whitefish Point, but that was not to be. I think that just the questions behind the shipwrecks on Lake Superior makes the thousands of shipwrecks a huge mystery.

I don’t often find myself traveling along on 1-90 in the Sundance, Wyoming area, but when I did back in 2014, I was surprised to see a very low flying airplane coming toward us, or I thought it was at first. The bright yellow Beachcraft Twin Bonanza was actually perched upon a 70 foot pole beside the road. The owners of the plane, Mick and Jean Quaal lived the antique plane, but the cost to put it back in flying condition was in the neighborhood of $200,000. Still, they hated to see the beautiful relic sitting on the ground just rusting away.

I don’t often find myself traveling along on 1-90 in the Sundance, Wyoming area, but when I did back in 2014, I was surprised to see a very low flying airplane coming toward us, or I thought it was at first. The bright yellow Beachcraft Twin Bonanza was actually perched upon a 70 foot pole beside the road. The owners of the plane, Mick and Jean Quaal lived the antique plane, but the cost to put it back in flying condition was in the neighborhood of $200,000. Still, they hated to see the beautiful relic sitting on the ground just rusting away.

So, they came up with a plan to give the plane another chance to fly. It was a perfect plan. The flame was flying again, and every person who drove down I-90 could see it. The plane is not sitting in a locked position, but rather can turn with the wind, basically making it a very expensive windsock. Raising it in place took the assistance of a flatbed truck, a crane, a manlift and several people guiding the aircraft with ropes, says Jean. “I call it a monument to aviation – and  the area’s largest windsock,” she laughs. “The plane turns in the direction of the wind,” adds Mick, “and those who look closely might even see its propellers spinning.”

the area’s largest windsock,” she laughs. “The plane turns in the direction of the wind,” adds Mick, “and those who look closely might even see its propellers spinning.”

It is believed to be a D50E model, but there is not much of a differences between the models. The Twin Bonanza was first flown in 1949 and production began in 1951. The United States Army adopted the Twin Bonanza as the L-23 “Seminole” utility transport, purchasing 216 of the 994 that were built. The pole had to be pretty big, because the wingspan of a Twin Bonanza is 45 feet. The fuselage length is about 31 feet. There is what appears to be a device a pivot under the airplane that allows it to rotate with the wind. And if people look closely, they can see that the propellers rotate freely in the wind. Owned by Mick and Jean Quaal, the plane has a large Q painted on the side. While I had been surprised to see the plane so low to the ground, I thought it was a great idea to let it be flying again.

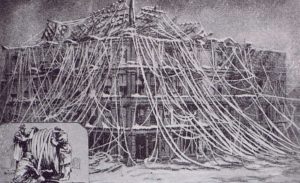

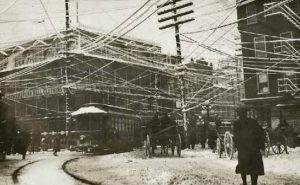

Sometimes, a picture can instill such a strange awareness within us that it is hard to get the picture out of our heads. It doesn’t have to be something horrible, bloody, or shocking, but simply something unusual. The phone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, built in 1887 is that kind of a picture, for sure.

Sometimes, a picture can instill such a strange awareness within us that it is hard to get the picture out of our heads. It doesn’t have to be something horrible, bloody, or shocking, but simply something unusual. The phone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, built in 1887 is that kind of a picture, for sure.

Technology has changed so much over the years, and this tower was a relic of the past. That is probably why the image has stuck in my head all this time. The tower served its purpose at the time, connecting 5,000 telephone wires and providing service to all those people, but to me it seemed rather dangerous in many ways. The telephone was an amazing invention, but somehow, the idea of buried cable never occurred to the inventor or the engineers who made it a reality for everyone. The service was very expensive, and so only for the wealthy…a fact that would change in years to come.

Similar towers sprang up around the world, and most residents soon grew to hate the massive amounts of lines that littered their skyline. Still, it was the only way at the time, and the telephone was, after all, an important invention. Too bad they couldn’t immediately come up with the wireless version we all enjoy these days. The telephone towers were used shortly before telephone companies started burying their wires in about 1913.

The change was well received, since most residents hated it, and some of the work was done after a snowstorm downed telephone poles, causing the cities to pay for the changes. Soon the hated phone lines began to disappear. I can see why the towers are hated, and to this day, most photographers hate to have the towers

and wires in their photographs. I have often found myself wishing the wires were missing from that perfect shot I got as my husband and I walked along the walking paths in Casper, so I can understand the way the residents of Stockholm, New York, and Boston felt about the monstrosity that was the telephone lines in their cities. Thankfully for the residents, the problem was solved when the tower burned down on July 25, 1953.

and wires in their photographs. I have often found myself wishing the wires were missing from that perfect shot I got as my husband and I walked along the walking paths in Casper, so I can understand the way the residents of Stockholm, New York, and Boston felt about the monstrosity that was the telephone lines in their cities. Thankfully for the residents, the problem was solved when the tower burned down on July 25, 1953.

The debate between capitalism and communism is not new, and in fact has been going on for a long time. Possibly one of the strangest debates, known as the “kitchen debate” was between Vice President Nixon and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. The debate was heated at times, but what was strangest about the debate was the fact that it took place in the middle of a model kitchen set up for an exhibit. Why they would have such a discussion in a model kitchen at a national exhibit is the really beyond me, but that is where it took place.

The debate between capitalism and communism is not new, and in fact has been going on for a long time. Possibly one of the strangest debates, known as the “kitchen debate” was between Vice President Nixon and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. The debate was heated at times, but what was strangest about the debate was the fact that it took place in the middle of a model kitchen set up for an exhibit. Why they would have such a discussion in a model kitchen at a national exhibit is the really beyond me, but that is where it took place.

The so-called “kitchen debate” became one of the most famous episodes of the Cold War, and many think it might have really led to fighting words, had it not been for the two men controlling their tempers in the end. The meeting was set up in late 1958. In an effort to draw the two nations closer together, the Soviet Union and the United States agreed to set up national exhibitions in each other’s nation as part of their new emphasis on cultural exchanges. The Soviet exhibition opened in New York City in June 1959, and the United States exhibition opened in Sokolniki Park in Moscow in July. On July 24, before the Moscow exhibit was officially opened to the public, Vice President Nixon served as a host for a visit by Soviet leader Khrushchev. As Nixon led Khrushchev through the American exhibition, the Soviet leader’s famous temper began to flare. When Nixon demonstrated some new American color television sets, Khrushchev launched into an attack on the so-called “Captive Nations Resolution” passed by the United Stares Congress just days before. The resolution condemned the Soviet control of the “captive” peoples of Eastern Europe and asked all Americans to pray for their deliverance. I don’t suppose that resolution set well with Khrushchev, and coming right before the exhibition probably set the whole debate in motion.

After denouncing the resolution, Khrushchev then sneered at the United States technology on display, saying that the Soviet Union would have the same sort of gadgets and appliances within a few years. Nixon, was not a man to back down from a debate, so he cane right back and goaded Khrushchev by stating that the Russian leader should “not be afraid of ideas. After all, you don’t know everything.” The Soviet leader snapped at Nixon, “You don’t know anything about communism–except fear of it.” With a small army of reporters and photographers following them, Nixon and Khrushchev continued their argument in the kitchen of a model home built in the exhibition. With their voices rising and fingers pointing, the two men went at each other. I’m sure it was quite a show. Nixon suggested that Khrushchev’s constant threats of using nuclear missiles could lead to war, and he chided the Soviet for constantly interrupting him while he was speaking. Taking these words as a threat, Khrushchev warned of “very bad consequences.” Perhaps feeling that the exchange had gone too far, the Soviet leader then noted that he simply wanted “peace with all other nations, especially America.” Nixon,  feeling slightly embarrassed said that he had probably not “been a very good host.” The debate, so quickly inflamed, fizzled in much the same way…at least between the two men…not so much the media.

feeling slightly embarrassed said that he had probably not “been a very good host.” The debate, so quickly inflamed, fizzled in much the same way…at least between the two men…not so much the media.

The “kitchen debate” was front-page news in the United States the next day. For a few moments, in the confines of a “modern” kitchen, the diplomatic gloves had come off and America and the Soviet Union had verbally jousted over which system was superior…communism or capitalism. As with so many Cold War battles, however, there was no clear winner…except perhaps for the United States media, which had a field day with the dramatic encounter. It was the sensationalism that the news media craves.

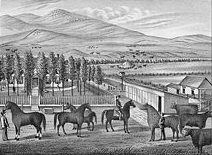

When Conrad Kohrs, immigrated to the United States at the age of 15, he was seeking his fortune like so many other immigrants were. The year was 1850, and while it is odd these days to think of a 15 year old boy immigrating to America alone now, it wasn’t entirely unheard of then. Kohrs was a native of Denmark, and had planned to head west to make his fortune in gold or silver. Unfortunately, while he had some small success in California and British Columbia, try as he might, the “big strike” always eluded Kohrs.

When Conrad Kohrs, immigrated to the United States at the age of 15, he was seeking his fortune like so many other immigrants were. The year was 1850, and while it is odd these days to think of a 15 year old boy immigrating to America alone now, it wasn’t entirely unheard of then. Kohrs was a native of Denmark, and had planned to head west to make his fortune in gold or silver. Unfortunately, while he had some small success in California and British Columbia, try as he might, the “big strike” always eluded Kohrs.

Kohrs tended to follow the crowd, and in 1862, he joined the latest western gold rush and headed for western Montana, where rich gold deposits had been found at Grasshopper Creek. It might be true that gold was plentiful at Grasshopper Creek, but Kohrs realized that he could make more money mining the miners than mining for gold. Miners need lots of supplies, and the man who was able to supply the needs, was the one who made money. He established a butcher shop in the mining town of Bannack and began to prosper.

His work as a butcher led Kohrs into the cattle business. Cattle were a big commodity, being in relatively short supply in frontier Montana. Much has changed today, and Kohrs had a big part in that. Kohrs traveled around the territory to purchase prime animals. He had several brushes with the highwaymen who plagued the isolated roads of Montana. Determined to stop these murderous bandits, Kohrs joined a group of Virginia City vigilantes, and helped track down and hang the outlaws. By 1864, robberies in the territory had plummeted. Proper or not, vigilante justice, got the point across very well.

Whether he was good at being part of a vigilante group or not, it couldn’t be what made his living. Kohrs began shifting the focus of his meat processing business to the supply side. In 1864, he established a large ranch near the town of Deer Lodge, where he fattened his cattle for market. Kohrs was pretty much the only major rancher in the western region of the territory. This caused his business to boom as Montana grew. As always happens, eventually, competition from cattle driven overland into the territory from Texas began to challenge Kohrs’ monopoly. Nevertheless, he continued to prosper, and remained the largest cattle rancher in Montana for several decades.

Kohrs entered the political arena in 1885, translating his economic strength into political power. He was elected to the Montana Territorial Legislature. Kohrs and his fellow ranchers had considerable influence over Montana in the years to come, and Kohrs went on to become a state senator in 1902. The big ranchers never had a free hand in Montana, however, because mining interests and farmers always kept the ranchers in check, but it wasn’t for a lack of trying. Kohrs was widely celebrated as one of the greatest pioneers in Montana history. He died on July 23, 1920 at the age of 85 in Helena.

For many years, levee systems were built along rivers to hold back flood waters. They work very well…until they don’t. When a levee ruptures, the resulting flood is usually devastating. From June through August of 1993, the midwestern United States received an unusually large amount of rain…far more than normal. The rain led to severe flooding, particularly along the Illinois and Missouri shores. Then, on July 22, 1993, the levee holding back the flooding Mississippi River at Kaskaskia, Illinois, ruptured. The town’s people were forced to flee on barges. In all, more than 1,000 levees burst in late July, but, the incident at Kaskaskia was the most dramatic event of the flood. The town, which was virtually an island, was protected by a levee that the town attempted to shore up even after the bridge connecting the town to the riverside was wiped out by the rising river. At

For many years, levee systems were built along rivers to hold back flood waters. They work very well…until they don’t. When a levee ruptures, the resulting flood is usually devastating. From June through August of 1993, the midwestern United States received an unusually large amount of rain…far more than normal. The rain led to severe flooding, particularly along the Illinois and Missouri shores. Then, on July 22, 1993, the levee holding back the flooding Mississippi River at Kaskaskia, Illinois, ruptured. The town’s people were forced to flee on barges. In all, more than 1,000 levees burst in late July, but, the incident at Kaskaskia was the most dramatic event of the flood. The town, which was virtually an island, was protected by a levee that the town attempted to shore up even after the bridge connecting the town to the riverside was wiped out by the rising river. At  9:48am, the levee broke, leaving the people of Kaskaskia with no escape route other than two Army Corp of Engineers barges. By 2pm, the entire town was underwater.

9:48am, the levee broke, leaving the people of Kaskaskia with no escape route other than two Army Corp of Engineers barges. By 2pm, the entire town was underwater.

The rupture of the levee at Quincy, Illinois, left no way to cross the Mississippi River for 250 miles north of Saint Louis. In Grafton, Illinois, flood waters reached two stories high. Other towns fared somewhat better, but the flooding was bad everywhere. In Saint Genevieve, Missouri, the entire town turned out in a desperate attempt to raise the levee. Prisoners were even brought in to assist the effort. The river crested at a record 49 feet, just two feet below the improved levee. The flood inundated 1 million acres of prime farm land and wreaked havoc on the area’s economy. Miles of wheat fields were too saturated to harvest that season. In addition, the herbicides from the farms washed down the river and severely damaged fish farms in Louisiana. Many other people lost their jobs when barge traffic on the river was suspended for two months. The Mississippi  flood of 1993 caused $18 billion in damages and killed 52 people.

flood of 1993 caused $18 billion in damages and killed 52 people.

Levees can save lives, but when levees fail…people die, and property is destroyed. Sometimes, there is some warning, but other times, the flood that was expected, brings with it an unexpected consequence. And I can’t think of a worse unexpected consequence, than having far more water inundate an area that the flood could possibly have brought in. That was the case in 1993, and especially the case in Kaskaskia, Illinois. No one was prepared for the massive amount of water, and for 52 people, there was no way of escape.