History

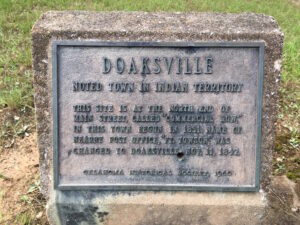

Many factors go into the “make or break” status of a town. Sometimes, it’s all about location. Other times, it’s about what is built after the town is formed. Still other times, it’s about what is discovered there and how low its supply lasts. The town of Doaksville, Oklahoma was once the largest town in the Choctaw Nation. Doaksville was founded in the early 1820s when Josiah S Doaks and his brother established a trading post. It was a humble beginning that sprang from the anticipation of the arrival of the Choctaw Indians to the area after the signing of the Treaty of Doak’s Stand in October 1820. The brothers moved westward with their boats filled with goods for the trading post and headed up the Mississippi and Red Rivers. Soon, other settlers moved into the area to be close to the store for mutual protection.

Many factors go into the “make or break” status of a town. Sometimes, it’s all about location. Other times, it’s about what is built after the town is formed. Still other times, it’s about what is discovered there and how low its supply lasts. The town of Doaksville, Oklahoma was once the largest town in the Choctaw Nation. Doaksville was founded in the early 1820s when Josiah S Doaks and his brother established a trading post. It was a humble beginning that sprang from the anticipation of the arrival of the Choctaw Indians to the area after the signing of the Treaty of Doak’s Stand in October 1820. The brothers moved westward with their boats filled with goods for the trading post and headed up the Mississippi and Red Rivers. Soon, other settlers moved into the area to be close to the store for mutual protection.

There were raids from the Plains Indians, especially those from Texas, which necessitated the establishment in 1824, of nearby Fort Towson. With the establishment of the fort, Doaksville began to grow and had all the makings of becoming a permanent town. Roads were built, between Doaksville, the trading post, and Fort Towson to establish a supply line. Doaksville sat at the center of these crossroads, and Doaksville began to prosper from the Central National Road of Texas that ran from Dallas to the Red River before connecting with the Fort Towson Road, which went on to Fort Gibson and beyond to Fort Smith, Arkansas. Doaksville seemed to be right in the thick of things. In addition, steamboats on the Red River connected with New Orleans at a public landing just a few miles south of Doaksville, carrying supplies to Fort Towson and agriculture products out of the region. It looked like Doaksville was headed for greatness.

Then, in 1837, the Choctaw and the Chickasaw signed the Treaty of Doaksville, which allowed the Chickasaw to lease the westernmost portion of the Choctaw Nation for settlement. By 1840, Doaksville was really growing. It now sported five large merchandise stores, two of which were owned by Choctaw Indians and the others by licensed white traders. There was a harness and saddle shop, wagon yard, blacksmith shop, gristmill, hotel, council house, and church. A newspaper called the Choctaw Intelligencer…printed in both English and Choctaw.

Of course, with the settlement came the missionaries. A missionary named Alvin Goode described the settlement at the time, “The trading establishment of Josiah Doak and Vinson Brown Timms, an Irishman, had the contract to supply the Indians their rations, figured at 13 cents a ration. A motley crowd always assembled  at Doaksville on annuity days to receive them. Some thousands of Indians were scattered over a nearly square mile tract around the pay house. There were cabins, tents, booths, stores, shanties, wagons, carts, campfires; white, red, black and mixed in every imaginable shade and proportion and dressed in every conceivable variety of style, from tasty American clothes to the wild costumes of the Indians; buying, selling, swapping, betting, shooting, strutting, talking, laughing, fiddling, eating, drinking, smoking, sleeping, seeing and being seen, all bundled together.”

at Doaksville on annuity days to receive them. Some thousands of Indians were scattered over a nearly square mile tract around the pay house. There were cabins, tents, booths, stores, shanties, wagons, carts, campfires; white, red, black and mixed in every imaginable shade and proportion and dressed in every conceivable variety of style, from tasty American clothes to the wild costumes of the Indians; buying, selling, swapping, betting, shooting, strutting, talking, laughing, fiddling, eating, drinking, smoking, sleeping, seeing and being seen, all bundled together.”

The town of Doaksville continued to grow, and in 1847 a post office was established. By 1850, the town had grown to more than thirty buildings, including stores, a jail, a school, a hotel, and two newspapers. Now established, it became the capital of the Choctaw Nation. For the next several years, Doaksville continued to thrive. Then, in 1854 Fort Towson was abandoned, and that spelled disaster for Doaksville. Without the business from the soldiers at the fort, Doaksville began to decline. Nevertheless, it would remain the tribal capital for the next nine years.

The Civil War, which broke out in 1861, spelled disaster for Doaksville. The region’s plantation-based economy was hit especially hard. In 1863, the Choctaw capital was moved to Chahta Tamaha, where it would remain until 1882, when it was moved for a third and final time to Tuskahoma, Oklahoma. The largest force in the Indian Territory was commanded by Confederate Brigadier General Stand Watie, chief of the Cherokee Nation. He was not one to admit defeat, and he would become the last Confederate general to surrender his command. When the leaders of the Confederate Indians learned that the government in Richmond, Virginia, had fallen and the Eastern armies had surrendered, most began making plans for surrender. The chiefs convened the Grand Council on June 15, 1865, and passed resolutions calling for Indian commanders to lay down their arms. Brigadier General Stand Watie refused until June 23, 1865, 75 days after Lee’s surrender in the East. At that point, he finally accepted the futility of continued resistance. He surrendered his battalion of Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, and Osage Indians to Lieutenant Colonel Asa C Matthews at Doaksville.

The collapse of the southern economy based on slave labor basically signed the death warrant Doaksville, and with the construction of the Saint Louis and San Francisco Railroad through the Southern Choctaw Nation in 1900-1901, its fate was sealed. At that time, the few buildings that remained at Doaksville were abandoned or moved to a new town that formed near the railroad, taking the name of the old post…Fort Towson. In 1903, the name of the Doaksville post office was changed to Fort Towson.

In 1960, the old town of Doaksville was acquired by the Oklahoma Historical Society. Little remained on the surface to betray its former importance, but in the 1990s, several archaeological excavations occurred, exposing the foundations of several buildings, including a jail, wells, a store, a hotel, and thousands of artifacts.

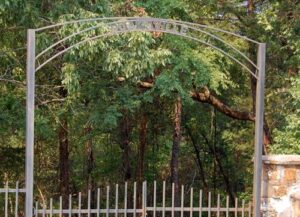

Today, a walking trail leads visitors through the site with interpretive signs telling the history of the old settlement. The old townsite has been designated as a National Historic Site, can be accessed through the Fort Towson Cemetery. A portion of the cemetery holds the burial sites of many important people who lived and died in Doaksville.

Today, a walking trail leads visitors through the site with interpretive signs telling the history of the old settlement. The old townsite has been designated as a National Historic Site, can be accessed through the Fort Towson Cemetery. A portion of the cemetery holds the burial sites of many important people who lived and died in Doaksville.

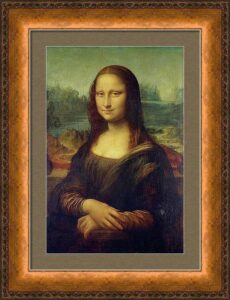

On August 21, 1911, the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre Museum in Paris, in what seemed like an impossible scenario. The theft of the Mona Lisa was called “art heist of the century,” but it was actually pretty basic. A small, mustached man entered the Louvre Museum in Paris, on the evening of Sunday, August 20, 1911, and made his way to the Salon Carré, where the Da Vinci painting was housed alongside several other masterworks. Maybe the museum didn’t think a theft could happen to them, it’s hard to say, but security in the museum was lax, so the man found it easy to stow away inside a storage closet. He remained hidden there until the following morning when the Louvre was closed, and there were few people around. He saw his chance to escape at around 7:15 am. He put on one of the white aprons worn by the museum’s employees. Then after checking to see if the coast was clear, he walked up to the Mona Lisa, took if off of the wall and carried it to a nearby service stairwell. There he removed it from the frame and tried to exit the stairwell into a courtyard. The door was locked, so he placed the Mona Lisa, which he had wrapped in a white sheet, on the floor and tried to take apart the doorknob. That got him nowhere, but an unsuspecting Louvre employee

On August 21, 1911, the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre Museum in Paris, in what seemed like an impossible scenario. The theft of the Mona Lisa was called “art heist of the century,” but it was actually pretty basic. A small, mustached man entered the Louvre Museum in Paris, on the evening of Sunday, August 20, 1911, and made his way to the Salon Carré, where the Da Vinci painting was housed alongside several other masterworks. Maybe the museum didn’t think a theft could happen to them, it’s hard to say, but security in the museum was lax, so the man found it easy to stow away inside a storage closet. He remained hidden there until the following morning when the Louvre was closed, and there were few people around. He saw his chance to escape at around 7:15 am. He put on one of the white aprons worn by the museum’s employees. Then after checking to see if the coast was clear, he walked up to the Mona Lisa, took if off of the wall and carried it to a nearby service stairwell. There he removed it from the frame and tried to exit the stairwell into a courtyard. The door was locked, so he placed the Mona Lisa, which he had wrapped in a white sheet, on the floor and tried to take apart the doorknob. That got him nowhere, but an unsuspecting Louvre employee  thought he was one of the Louvre’s plumbers, opened the door and let him out. He thanked the man and walked away.

thought he was one of the Louvre’s plumbers, opened the door and let him out. He thanked the man and walked away.

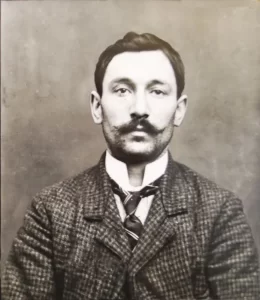

Then on September 7, 1911, came a shocking arrest. French poet Guillaume Apollinaire was jailed on suspicion of stealing Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa from the Louvre Museum in Paris. Apollinaire was a 31-year-old poet, who was known for his radical views and support for “extreme avant-garde” art movements, but his origins were shrouded in mystery. These days, it is believed that he was born in Rome and raised in Italy. At age 20, He moved to Paris and quickly blended in with the city’s bohemian crowd. His first volume of poetry, The Rotting Magician, appeared in 1909, followed by a story collection in 1910. Apollinaire was a supporter of Cubism, he published a book about the subject, Cubist Painters, in 1913. Cubism is “a revolutionary style of visual art invented by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the early 20th century1. It is an influential modernist art movement that emerged in Paris, characterized by the transformation of objects and subjects  into geometric shapes, often resembling cubes or facets.” The same year, he published his most esteemed work, Alcools, where he used a variety of poetic forms and traditions to capture everyday street speech. His experimental play The Breasts of Tiresias was produced in 1917, for which he coined the term “surrealist.”

into geometric shapes, often resembling cubes or facets.” The same year, he published his most esteemed work, Alcools, where he used a variety of poetic forms and traditions to capture everyday street speech. His experimental play The Breasts of Tiresias was produced in 1917, for which he coined the term “surrealist.”

His poetic works were inspirational, but Apollinaire’s mysterious background and radical views led authorities to view him as a dangerous foreigner and therefore a prime suspect in the Mona Lisa heist. Still with all their searching, they could find no evidence that linked Apollinaire to the theft. Apollinaire was released after five days. It seemed that the Mona Lisa, which is today valued at about 1 billion dollars, was lost forever. Then two years later, a former employee of the Louvre, Vincenzo Peruggia, was arrested while trying to sell the famous painting to an art dealer. He had been the bold thief and Apollinaire had simply been wrongfully accused.

Whether Robert Lincoln’s presence at or near a presidential assassination had anything to do with bringing it to pass or not, is irrelevant…he began to think his presence was relevant. Robert Todd Lincoln was Abraham Lincoln’s son, and while he wasn’t present at his father’s assassination, he was close. He was at the White House, and upon hearing of the assassination, he rushed to be with his parents. The president was moved to the Petersen House after the shooting, where Robert attended his father’s deathbed…and so began a series of strange coincidences in which Robert Todd Lincoln was either present or nearby when three presidential assassinations occurred. It isn’t surprising that Robert Lincoln began to think that maybe he was a “jinx” or “bad luck” if he was at a presidential event, but of course that was not the case. It was just what he believed.

Whether Robert Lincoln’s presence at or near a presidential assassination had anything to do with bringing it to pass or not, is irrelevant…he began to think his presence was relevant. Robert Todd Lincoln was Abraham Lincoln’s son, and while he wasn’t present at his father’s assassination, he was close. He was at the White House, and upon hearing of the assassination, he rushed to be with his parents. The president was moved to the Petersen House after the shooting, where Robert attended his father’s deathbed…and so began a series of strange coincidences in which Robert Todd Lincoln was either present or nearby when three presidential assassinations occurred. It isn’t surprising that Robert Lincoln began to think that maybe he was a “jinx” or “bad luck” if he was at a presidential event, but of course that was not the case. It was just what he believed.

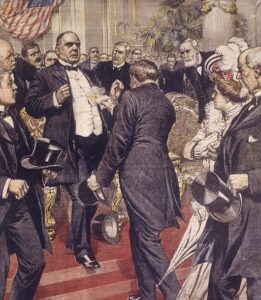

Robert was at the Sixth Street Train Station in Washington DC, at President James A Garfield’s invitation, when the President Garfield was shot by Charles J Guiteau on July 2, 1881. In fact, Robert was an eyewitness to the event. He was actually serving as Garfield’s Secretary of War at the time. President Garfield, the 20th president of the United States, was shot at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington DC at 9:30 am on Saturday, July 2, 1881. He actually lived two and a half months before passing away in Elberon, New Jersey, on September 19, 1881.

Then, on September 6, 1901, at President William McKinley’s invitation, Robert Lincoln was at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. For Robert, it happened again. The president was shot by Leon Czolgosz and though Robert was not an eyewitness to the event, he was just outside the building where the shooting occurred. Robert Lincoln saw these coincidences, and it really began to bother him, even though there was

really no rational connection. The concern for Robert Lincoln was so great that he is said to have refused a later presidential invitation with the comment, “No, I’m not going, and they’d better not ask me, because there is a certain fatality about presidential functions when I am present.” While I don’t think his presence had anything to do with the assassinations, I think that Robert Lincoln suffered great distress from the things he witnessed or almost witnessed. That really must have been an absolutely horrible feeling for him.

really no rational connection. The concern for Robert Lincoln was so great that he is said to have refused a later presidential invitation with the comment, “No, I’m not going, and they’d better not ask me, because there is a certain fatality about presidential functions when I am present.” While I don’t think his presence had anything to do with the assassinations, I think that Robert Lincoln suffered great distress from the things he witnessed or almost witnessed. That really must have been an absolutely horrible feeling for him.

Fog delayed the departure of on September 4, 1963, but the delay was not able to save the plane or its passengers. Swissair Flight 306, a Sud Aviation SE-210 Caravelle III, named Schaffhausen, was scheduled to fly internationally from Zürich to Rome, with a stop in Geneva. Unfortunately, it crashed near Dürrenäsch, Aargau, shortly after take-off, killing all 80 people on board.

Fog delayed the departure of on September 4, 1963, but the delay was not able to save the plane or its passengers. Swissair Flight 306, a Sud Aviation SE-210 Caravelle III, named Schaffhausen, was scheduled to fly internationally from Zürich to Rome, with a stop in Geneva. Unfortunately, it crashed near Dürrenäsch, Aargau, shortly after take-off, killing all 80 people on board.

The plane was due to take off at 06:00 UTC, but the fog was throwing everything off. At 06:04 the flight was allowed to taxi to runway 34 behind an escorting vehicle, to await clearance. Then the crew of Swissair Flight 306, decided to taxi slowly down the runway at 06:05 to inspect the fog. Then they would return to the take off point. Part of the plan was to use high engine power in order to disperse the fog. It must have worked, because around 06:12 the Swissair Flight 306 returned to runway 34 and was allowed to take off. The flight took off at 6:13 and started to climb to flight level 150, which is about 15,000 feet, which would be its cruising altitude.

A short four minutes later, people on the ground witnessed a white trail of smoke coming from the left side of the aircraft. The white streak of smoke gave way to a long flame that erupted from the left wing. Around 06:20 the aircraft reached a height of about 8,900 feet. At that level, the plane began to descend and banking gently to the left before losing altitude more quickly and finally going into a steep and final dive. At 6:21 a frantic mayday message was issued. Then, at 6:22 the Swissair Flight 306 crashed into the ground on the outskirts of Dürrenäsch, approximately 22 miles from Zürich Airport.

So, what brought this plane down just minutes after takeoff. The taxi down the runway in an effort to clear the fog…believe it or not. When the plane went down the runway using full engine power, the pilot also applied the brakes so the plane wouldn’t try to take off. The brakes overheated, causing the magnesium wheels to burst. One of them burst on the runway prior to departure. Then, when the landing gear was retracted, the hydraulic lines in the gear bay were damaged, causing the hydraulic fluid to leak and ignite. The fire damaged the gear bay, and then the wing. Upon looking at the data from the airplane’s flight recorder, it was determined that the crew began experiencing difficulties at 6:18. The data became irregular beginning roughly two minutes later,  indicating that the fire was causing electrical problems. Analysis of the wreckage indicated that parts of the airplane began detaching “with increasing frequency” at about 6:18. The left engine had shut down prior to the crash, but it is uncertain whether this was from crew action, or a failure caused by the fire. The actual cause for the final loss of control was not conclusively determined, but it seems likely that loss of hydraulics played a key part in it. The rigidity of the left wing and rear fuselage, the integrity of the hydraulic flight control system, and the elevator control unit were all noted as possible areas the fire may have affected in the final portion of the flight to an extent which would have caused a rapid loss of control. In the end, all Caravelles were modified to use non-flammable hydraulic fluids, to avoid a recurrence of this tragedy.

indicating that the fire was causing electrical problems. Analysis of the wreckage indicated that parts of the airplane began detaching “with increasing frequency” at about 6:18. The left engine had shut down prior to the crash, but it is uncertain whether this was from crew action, or a failure caused by the fire. The actual cause for the final loss of control was not conclusively determined, but it seems likely that loss of hydraulics played a key part in it. The rigidity of the left wing and rear fuselage, the integrity of the hydraulic flight control system, and the elevator control unit were all noted as possible areas the fire may have affected in the final portion of the flight to an extent which would have caused a rapid loss of control. In the end, all Caravelles were modified to use non-flammable hydraulic fluids, to avoid a recurrence of this tragedy.

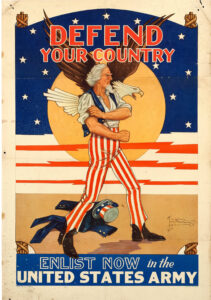

Understandably, the size of the various armies has grown along with human civilization. It is estimated that nearly 28 million armed forces personnel stand at the ready globally in this present day, according to the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of course, peacetime armies would likely be smaller than wartime armies. World War II saw the most soldiers ever to be amassed…with about 70 million soldiers. Approximately 42 million of those soldiers were from the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Japan. These nations armies and related services were four of the largest ever rallied to the battlefield. The largest three were the United States (12,209,000 troops in August 1945), the German Reich (12,070,000 troops in June 1944), and the Soviet Union (11,000,000 troops in June 1943). Those numbers are staggering to think about.

Understandably, the size of the various armies has grown along with human civilization. It is estimated that nearly 28 million armed forces personnel stand at the ready globally in this present day, according to the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of course, peacetime armies would likely be smaller than wartime armies. World War II saw the most soldiers ever to be amassed…with about 70 million soldiers. Approximately 42 million of those soldiers were from the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Japan. These nations armies and related services were four of the largest ever rallied to the battlefield. The largest three were the United States (12,209,000 troops in August 1945), the German Reich (12,070,000 troops in June 1944), and the Soviet Union (11,000,000 troops in June 1943). Those numbers are staggering to think about.

As is expected in a world war, many soldiers are needed. So, the World War II army of the US became the biggest army in history. Citizens of the United States are notorious for patriotism, when we have been attacked. It is like waking a sleeping giant, and we will retaliate with a vengeance. Due in part to that surge of American patriotism and also because of conscription (the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service,

mainly a military service), the US Army numbered 12,209,000 soldiers by the end of the war in 1945. It is little surprise that the Japanese found themselves surrendering to the United States on this day, September 2, 1945. of course, the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left little doubt that the Americans not only had the atomic bomb, but we would us it. Basically, their choices were to stay in the fight and die or surrender. They chose the latter, and the rest is history.

mainly a military service), the US Army numbered 12,209,000 soldiers by the end of the war in 1945. It is little surprise that the Japanese found themselves surrendering to the United States on this day, September 2, 1945. of course, the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left little doubt that the Americans not only had the atomic bomb, but we would us it. Basically, their choices were to stay in the fight and die or surrender. They chose the latter, and the rest is history.

In order to determine which of the armies were the largest in history, 24/7 Wall Street reviewed a list of military superpowers from Business Insider. These armies were ranked based on the total number of troops that were serving a country or empire at the point when the army was at its largest. Without doubt, the United States was, and remains to this day, the nation with the largest army in history. Over the years, the armed forces of the United States have been larger and smaller, depending on the need at the time, the administration

in charge, and since the draft was discontinued, the number of people who chose to join up to serve their country and to qualify for the GI Bill so that they can get free college. No matter how they got in the service, or how long they stayed, I am very proud of all of our soldiers over the many years of this nation…and I thank them for their service. On this day, the largest army in history accepted the surrender of the Japanese, who had once had the nerve to attack us on our own soil. That was their biggest mistake ever.

in charge, and since the draft was discontinued, the number of people who chose to join up to serve their country and to qualify for the GI Bill so that they can get free college. No matter how they got in the service, or how long they stayed, I am very proud of all of our soldiers over the many years of this nation…and I thank them for their service. On this day, the largest army in history accepted the surrender of the Japanese, who had once had the nerve to attack us on our own soil. That was their biggest mistake ever.

It was a typical lunch hour in Japan’s capital city of Tokyo, and the neighboring “City of Silk” Yokohama that September 1, 1923. People were out and about doing their normal lunchtime things, eating and running errands before going back to work. Suddenly the days routine was shattered when a massive, 7.9-magnitude earthquake struck just before noon. The shaking lasted just 14 seconds, but that was all it took to bring down nearly every building in Yokohama, which is just south of Tokyo. The shaking also caused more than half of Tokyo’s brick buildings, most of Yokohama’s buildings, and hundreds of thousands of homes to collapse, killing tens of thousands of people instantly.

It was a typical lunch hour in Japan’s capital city of Tokyo, and the neighboring “City of Silk” Yokohama that September 1, 1923. People were out and about doing their normal lunchtime things, eating and running errands before going back to work. Suddenly the days routine was shattered when a massive, 7.9-magnitude earthquake struck just before noon. The shaking lasted just 14 seconds, but that was all it took to bring down nearly every building in Yokohama, which is just south of Tokyo. The shaking also caused more than half of Tokyo’s brick buildings, most of Yokohama’s buildings, and hundreds of thousands of homes to collapse, killing tens of thousands of people instantly.

Known as the Great Kanto Earthquake, but also called the Tokyo-Yokohama Earthquake, of 1923, it caused an estimated death toll of more than 140,000 and left some 1.5 million people homeless, according to reported numbers. Following the earthquake came another disaster in the form of fires that burned many buildings. Most likely, this was because in 1923, people cooked over an open flame, and the quake struck while people were preparing lunch. To further complicate matters, the area was hit by high winds, caused by a typhoon that passed off the coast of the Noto Peninsula in northern Japan, spread the flames and created horrifying firestorms. Because the quake had snapped water mains, the fires could not be extinguished until September 3rd. By that time, about 45 percent of Tokyo had burned. Some researchers believed that the typhoon may have triggered the earthquake, because the forced atmospheric pressure pressed on a stressed and delicate fault line of three major tectonic plates that meet under Tokyo. I wasn’t aware that this was possible, but  apparently it is. The quake also triggered a tsunami that swelled to 39.5 feet at Atami on the Sagami Gulf, where 60 people were killed and 155 homes destroyed.

apparently it is. The quake also triggered a tsunami that swelled to 39.5 feet at Atami on the Sagami Gulf, where 60 people were killed and 155 homes destroyed.

The damage from all this in Toyko was so severe that some government leaders argued for moving the Japanese capital to a new city. Educator, Miura Tosaku toured the destruction of Tokyo in the fall of 1923, concluded that the earthquake was an apocalyptic revelation. He wrote: “Disasters take away the falsehood and ostentation of human life and conspicuously expose the strengths and weaknesses of human society.” Tenrikyo relief worker Haruno Ki’ichi said, “The destruction and devastation in the earthquake aftermath surpassed imagination.”

Yokohama’s Victorian-era Grand Hotel, that had hosted famous people including US President William Howard Taft and English author Rudyard Kipling, completely collapsed. Hundreds of hotel employees and guests were crushed. Henry W Kinney, a Tokyo-based editor of the Trans-Pacific publication, observed the devastation in Yokohama hours after the earthquake hit. He wrote, “Yokohama, the city of almost half a million souls, had become a vast plain of fire, of red, devouring sheets of flame which played and flickered. Here and there a remnant of a building, a few shattered walls, stood up like rocks above the expanse of flame, unrecognizable … It was as if the very Earth were now burning. It presented exactly the aspect of a gigantic Christmas pudding over which the spirits were blazing, devouring nothing. For the city was gone.”

Since 1960, the Japanese people recognize the September 1 anniversary of the earthquake as Disaster Prevention Day. It’s a noble idea, but I’m not sure how these disasters could be prevented, other than the now common practice of earthquake proofing buildings to prevent so much loss. Nevertheless, Japan has suffered through several more devastating earthquakes. More than seven decades after the 1923 disaster, an earthquake struck Kobe on January 17, 1995. This Kobe Earthquake caused an estimated 6,400 deaths, widespread fires, and a landslide in Nishinomiya. Then, on March 11, 2011, a 9.0-magnitude temblor struck off th

e coast of Japan’s city of Sendai. This Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami caused a series of catastrophic tsunamis in Japan, and more than 18,000 estimated deaths. I suppose that to say the very least, the loss of life in these more recent quakes, was far less than in the original event that founded Disaster Prevent Day.

e coast of Japan’s city of Sendai. This Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami caused a series of catastrophic tsunamis in Japan, and more than 18,000 estimated deaths. I suppose that to say the very least, the loss of life in these more recent quakes, was far less than in the original event that founded Disaster Prevent Day.

The shaking began at 9:51pm that August 31, 1886, and by the time it was over, more than 100 people in Charleston, South Carolina would be dead and hundreds of buildings were destroyed. It wasn’t that there were no warnings. There were…unheeded warnings in the form of two foreshocks that were felt in Summerville, South Carolina, on August 27th and 28th, but no one was prepared for the strength of the August 31 quake. The quake was felt as far away as Boston, Chicago, and even Cuba. Buildings were damaged as far away as Ohio and Alabama.

The shaking began at 9:51pm that August 31, 1886, and by the time it was over, more than 100 people in Charleston, South Carolina would be dead and hundreds of buildings were destroyed. It wasn’t that there were no warnings. There were…unheeded warnings in the form of two foreshocks that were felt in Summerville, South Carolina, on August 27th and 28th, but no one was prepared for the strength of the August 31 quake. The quake was felt as far away as Boston, Chicago, and even Cuba. Buildings were damaged as far away as Ohio and Alabama.

Even with all that, it was Charleston, South Carolina that took the biggest hit from the quake. While quake measurements in those days were not as accurate as they are these days, this quake was thought to measure a magnitude of about 7.6. Almost all of the buildings in Charleston were seriously damaged. Approximately 14,000 chimneys fell from the earthquake. Multiple fires erupted, and water lines and wells were ruptured. The total damage was in excess of $5.5 million in those days, which would figure to approximately $115 million today. The greatest damage was done to buildings constructed out of brick, which amounted to 81% of building damage. The frame buildings suffered significantly less damage. Another factor that came into play was kind of  ground these buildings were built on. Buildings constructed on ground that had been built up to accommodate them (made ground), suffered significantly more damage than buildings constructed on solid ground, however, this relationship only occurred in wood-frame buildings. Approximately 14% of wood-frame buildings built on “made ground” sustaining damage, compared to 0.5% of wood-frame buildings built on solid ground sustaining damage.

ground these buildings were built on. Buildings constructed on ground that had been built up to accommodate them (made ground), suffered significantly more damage than buildings constructed on solid ground, however, this relationship only occurred in wood-frame buildings. Approximately 14% of wood-frame buildings built on “made ground” sustaining damage, compared to 0.5% of wood-frame buildings built on solid ground sustaining damage.

The residential buildings sustained significantly less damage than the more prominent commercial buildings, most of which were destroyed, or nearly so. This was due to the fact that commercial buildings were older, had a more prominent top compared to the base of the building, and were made of brick. The Old White Meeting House near Summerville, South Carolina was reduced to ruins. Many of the other man-made structures were also damaged as a result of earth splits caused by the earthquake. The railroad tracks in Charleston and nearby areas were snapped and trains were derailed. In addition, flooding occurred in surrounding farms and roads when dams broke. Acres of land actually liquefied in many spots, which further damaged many buildings, roads, bridges, and farm fields.

Strangely, for an earthquake of this magnitude anyway, was the fact that there were no apparent surface cracks as a result of this tremor, but railroad tracks were bent in all directions in some locations. The true cause of this quake remained a mystery for many years, because there were no known underground faults for 60

miles in any direction. However, now, with better science and detection methods, scientists have recently uncovered a “concealed fault” along the coastal plains of Virginia and the Carolinas. While there is now a known fault, a quake of this magnitude is highly unlikely in this location. Nevertheless, this was the largest recorded earthquake in the history of the southeastern United States.

miles in any direction. However, now, with better science and detection methods, scientists have recently uncovered a “concealed fault” along the coastal plains of Virginia and the Carolinas. While there is now a known fault, a quake of this magnitude is highly unlikely in this location. Nevertheless, this was the largest recorded earthquake in the history of the southeastern United States.

I have never been to the top of Mount Washington in New Hampshire, but I am intrigued by it, and by everything I have heard about it. Mount Washington is notorious for its erratic weather. On the afternoon of April 12, 1934, the Mount Washington Observatory recorded a windspeed of 231 miles per hour at the summit, the world record from 1934 until 1996. Mount Washington still holds the record for highest measured wind speed not associated with a tornado or tropical cyclone. Can you just imagine trying to stand outside in that wind? I can’t imagine trying to stand out in that wind, especially in winter, but I can imagine seeing that place…maybe not on a really windy day, but just to see the top would be very cool.

I have never been to the top of Mount Washington in New Hampshire, but I am intrigued by it, and by everything I have heard about it. Mount Washington is notorious for its erratic weather. On the afternoon of April 12, 1934, the Mount Washington Observatory recorded a windspeed of 231 miles per hour at the summit, the world record from 1934 until 1996. Mount Washington still holds the record for highest measured wind speed not associated with a tornado or tropical cyclone. Can you just imagine trying to stand outside in that wind? I can’t imagine trying to stand out in that wind, especially in winter, but I can imagine seeing that place…maybe not on a really windy day, but just to see the top would be very cool.

There are basically three ways to get to the top of Mount Washington. The first is to drive up on the Mount Washington Auto Road. If you choose this one, you can get one of the This Car Climbed Mount Washington  bumper stickers that are common throughout New England following your trip up the mountain, but to me that rather defeats the purpose reaching the summit. Now, if a person is an experienced hiker, there is a hiking trail to the top. And if you are really fanatical, you can hike it in Winter, taking the Snow Coach halfway up. Now, I like to hike, but definitely not in the Winter. One of the shortest, most scenic, and most popular trails to the summit is the 4.2-mile class 2 Tuckerman Ravine Trail that starts at the AMC Pinkham Notch Visitor Center (2050′). While 4.2 miles is doable, the class 2 part, meaning “more difficult hiking that may be off-trail. You may also have to put your hands down occasionally to keep your balance. May include easy snow climbs or hiking on talus/scree. Class 2 includes a wide range of hiking, and a route may have exposure, loose rock, steep scree, etc” is a little more off-putting for me.

bumper stickers that are common throughout New England following your trip up the mountain, but to me that rather defeats the purpose reaching the summit. Now, if a person is an experienced hiker, there is a hiking trail to the top. And if you are really fanatical, you can hike it in Winter, taking the Snow Coach halfway up. Now, I like to hike, but definitely not in the Winter. One of the shortest, most scenic, and most popular trails to the summit is the 4.2-mile class 2 Tuckerman Ravine Trail that starts at the AMC Pinkham Notch Visitor Center (2050′). While 4.2 miles is doable, the class 2 part, meaning “more difficult hiking that may be off-trail. You may also have to put your hands down occasionally to keep your balance. May include easy snow climbs or hiking on talus/scree. Class 2 includes a wide range of hiking, and a route may have exposure, loose rock, steep scree, etc” is a little more off-putting for me.

That leaves the final, and for me, most intriguing way to make the summit…the Mount Washington Cog Railway. While the other ways to reach the summit are very cool, the Cog is special!! This is basically a mountain climbing train. It’s a unique journey that is as much of a fun retro adventure as it is an impressive engineering

marvel. The track of the Cog Railway is approximately 3 miles long, and it ascends up Mount Washington’s western slope, beginning at an elevation of approximately 2,700 feet above sea level and ending just short of the mountain’s summit peak of 6,288 feet. The Cog is the second-steepest rack railway in the world to this day. It is second only to the Pitalus Railway in Switzerland.

marvel. The track of the Cog Railway is approximately 3 miles long, and it ascends up Mount Washington’s western slope, beginning at an elevation of approximately 2,700 feet above sea level and ending just short of the mountain’s summit peak of 6,288 feet. The Cog is the second-steepest rack railway in the world to this day. It is second only to the Pitalus Railway in Switzerland.

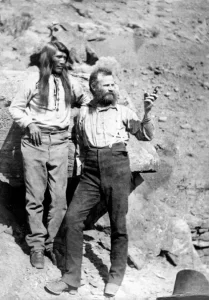

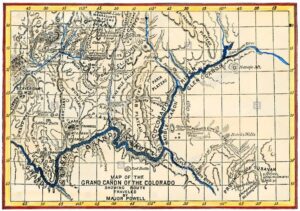

When John Wesley Powell began his expedition through the Grand Canyon he took eleven men with him. The plan was to explore the Grand Canyon by boat. Powell was a one-armed Civil War veteran and self-trained naturalist. The men had been on their expedition for about three months, when three of the men became very concerned about the safety of the mission. Some of the rapids had been heavy, and just ahead, they could hear what the worst of the rapids. The three men, terrified of the rapids that lay ahead, were convinced that they would have a better chance of survival, if they scaled the steep cliffs to the plateau above and walked out.

When John Wesley Powell began his expedition through the Grand Canyon he took eleven men with him. The plan was to explore the Grand Canyon by boat. Powell was a one-armed Civil War veteran and self-trained naturalist. The men had been on their expedition for about three months, when three of the men became very concerned about the safety of the mission. Some of the rapids had been heavy, and just ahead, they could hear what the worst of the rapids. The three men, terrified of the rapids that lay ahead, were convinced that they would have a better chance of survival, if they scaled the steep cliffs to the plateau above and walked out.

It would be hard to fault the men. When the party heard the rapids, they pulled to shore and walked down to see what lay ahead. Indeed, the worst was yet to come. Upon reaching the site of the rapids on foot, they saw, in the words of one man, “the worst rapids yet.” There was no argument from Powell, who wrote that, “The billows are huge, and I fear our boats could not ride them… There is discontent in the camp tonight, and I fear some of the party will take to the mountains but hope not.”

Indeed, the three men decided that they were not going to risk the rapids, so they scaled the cliffs…a move  that turned out to be not only a serious mistake but a fatal one. It wasn’t their fault really. They truly thought that Powell’s plan to float the brutal rapids was suicidal. The men were convinced that Powell’s four wooden boats would have been smashed to bits in the punishing rapids…the kind that many would hesitate to run even with modern rafts.

that turned out to be not only a serious mistake but a fatal one. It wasn’t their fault really. They truly thought that Powell’s plan to float the brutal rapids was suicidal. The men were convinced that Powell’s four wooden boats would have been smashed to bits in the punishing rapids…the kind that many would hesitate to run even with modern rafts.

The next day, three of Powell’s men did leave. Convinced that the rapids were impassable, they decided to take their chances crossing the harsh desert lands above the canyon rims. So, on August 28, 1869, Seneca Howland, O G Howland, and William H Dunn said goodbye to Powell and the other men and began the long climb up out of the Grand Canyon. Once the three men left, the rest of the party steeled themselves to the ordeal that lay ahead, climbed into boats, and pushed off into the wild rapids.

While it seemed like a suicide mission, all of men survived the rapids, and the expedition emerged from the canyon the next day. Sadly, when he reached the nearest settlement, Powell learned that the three men who left had not been for fortunate. Allegedly, they encountered a war party of Shivwit Native Americans, and all

three were killed. Ironically, the three murders were initially viewed as more newsworthy than Powell’s amazing feat and the expedition gained valuable publicity. When Powell planned a second trip through the Grand Canyon in 1871, the publicity from the first trip insured that the second voyage was far better financed than the first. Sadly, the increased financing for the expedition came at great cost…to the three men who were murdered anyway.

three were killed. Ironically, the three murders were initially viewed as more newsworthy than Powell’s amazing feat and the expedition gained valuable publicity. When Powell planned a second trip through the Grand Canyon in 1871, the publicity from the first trip insured that the second voyage was far better financed than the first. Sadly, the increased financing for the expedition came at great cost…to the three men who were murdered anyway.

As mining work started up in the United States, the need for housing in the area of the mines started up too. This need brought about the “company town” as a place where all or most of the stores and housing in the town are owned by the same company. Of course, this meant that quite often, all or most of the wages paid to workers, came back to the company in purchases, and as we all know stores and such always have a markup so that they make a profit. Still, they did meet a need, and there was often nowhere else to go. Company towns were often planned with a number of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schools, markets, and recreation facilities.

As mining work started up in the United States, the need for housing in the area of the mines started up too. This need brought about the “company town” as a place where all or most of the stores and housing in the town are owned by the same company. Of course, this meant that quite often, all or most of the wages paid to workers, came back to the company in purchases, and as we all know stores and such always have a markup so that they make a profit. Still, they did meet a need, and there was often nowhere else to go. Company towns were often planned with a number of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schools, markets, and recreation facilities.

The initial motive of building the “company towns” was to improve living conditions for workers. Nevertheless, many have been regarded as controlling and often exploitative. Others were not planned, such as Summit Hill, Pennsylvania, United States, one of the oldest, which began as a Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company mining camp and mine site nine miles from the nearest outside road. Just being that far from anything else around, was prohibitive to those who felt like they were the victims of gouging. Today, many of those “company towns” are ghost towns…lost to a bygone era.

One such town, the town of Kempton, West Virginia was located just a few feet inside the West Virginia border. This strategic location allowed the company to operate using scrip rather than cash. To me that seems like a move to a cashless system that further held the workers there, because the scrip was only accepted at the company businesses, thereby eliminating outside competition. As with any monopoly, this created price  gouging. To make matters worse, if an employee needed a “big ticket” item, such as such as washing machines, radios, and refrigerators, they could get them and make payments. This put many miners in debt, and they were required to pay off the debt before they could move away. The town of Kempton was “founded in 1913 by the Davis Coal and Coke Company, a strip of land 3/4 of a mile long and several hundred feet wide was cleared for the construction of company houses, four to six rooms each with a front yard and a garden in the back. In 1915, J Weimer became the first schoolteacher at $40 a month with 53 pupils. The company store was located on the West Virginia side along with the Opera House that contained the lunchroom, bowling alley, pool table, dancing floor, auditorium, and the post office.” These towns were in reality, “privatized” towns run by a government that was neither elected nor fair, they were simply the ones in control, and if people wanted a job they dealt with the rules.

gouging. To make matters worse, if an employee needed a “big ticket” item, such as such as washing machines, radios, and refrigerators, they could get them and make payments. This put many miners in debt, and they were required to pay off the debt before they could move away. The town of Kempton was “founded in 1913 by the Davis Coal and Coke Company, a strip of land 3/4 of a mile long and several hundred feet wide was cleared for the construction of company houses, four to six rooms each with a front yard and a garden in the back. In 1915, J Weimer became the first schoolteacher at $40 a month with 53 pupils. The company store was located on the West Virginia side along with the Opera House that contained the lunchroom, bowling alley, pool table, dancing floor, auditorium, and the post office.” These towns were in reality, “privatized” towns run by a government that was neither elected nor fair, they were simply the ones in control, and if people wanted a job they dealt with the rules.

Cut out of the Appalachian wilderness, the town of Kempton flourished and became a vibrant community rich in culture and familial spirit. Then, when the mine closed in April of 1950, it just as quickly faded into oblivion. Nevertheless, the former residents tried to keep their connections alive. They held a reunion in 1952 to share their memories and to recall a strong sense of home. Unfortunately, what were once good intention, faded as life got busy and people moved around. Finally, the forest began to reclaim many of the houses as weeds took over and neglect allowed for decay. These days, the fruit trees and annual flowers that were planted long ago

by people who loved the place “still bloom to greet the Spring” and a few of the broken-down buildings still dot the landscape, if one in incline to look around. Newer homes have been built, that are privately owned, and mixed in are a few of the old remnants of times past. With mine reclamation laws in place now, groups have come in and performed archeological digs to recover old work items from the past and restore the site to historical status.

by people who loved the place “still bloom to greet the Spring” and a few of the broken-down buildings still dot the landscape, if one in incline to look around. Newer homes have been built, that are privately owned, and mixed in are a few of the old remnants of times past. With mine reclamation laws in place now, groups have come in and performed archeological digs to recover old work items from the past and restore the site to historical status.