History

When people think of Venice, Italy, they think of the canals and the boats. I think most of us think the city is pretty much streets of water, and buildings that somehow stand in the water…strong and immovable against the water. Venice is the center of the lagoon of Venice, which extends over a length of 25 miles around the city. While it seems like the city is covered in water, only 11% of the lagoon is permanently covered with water, while the rest of the lagoon is islands or mudflats and marshes (Laguna Morta). The water stays fresh because, seawater from the Adriatic flows into the lagoon through three large passages, Bocca di Lido, Bocca di Malamocco, and Bocca di Chioggia, twice daily. This process provides a natural water exchange. Still, 11% water can sure look like a lot, especially when every touristy picture we see involves the canals and gondolas. So, to think of a situation whereby a flood could become tragic in Venice, is a strange thought for anyone who doesn’t really know Venice…like me.

When people think of Venice, Italy, they think of the canals and the boats. I think most of us think the city is pretty much streets of water, and buildings that somehow stand in the water…strong and immovable against the water. Venice is the center of the lagoon of Venice, which extends over a length of 25 miles around the city. While it seems like the city is covered in water, only 11% of the lagoon is permanently covered with water, while the rest of the lagoon is islands or mudflats and marshes (Laguna Morta). The water stays fresh because, seawater from the Adriatic flows into the lagoon through three large passages, Bocca di Lido, Bocca di Malamocco, and Bocca di Chioggia, twice daily. This process provides a natural water exchange. Still, 11% water can sure look like a lot, especially when every touristy picture we see involves the canals and gondolas. So, to think of a situation whereby a flood could become tragic in Venice, is a strange thought for anyone who doesn’t really know Venice…like me.

On December 1, 2008, Venice experienced the biggest flood in more than twenty years. The waters rose more than five feet above normal levels. As with any flood, many of Venice’s streets, including Saint Mark’s Square, were submerged. Venice has flooding for about two hundred days every year, and the Venetian authorities were working to complete an underwater dam by 2011. Unfortunately, that fact didn’t help the city in 2008. Even with unusually high tides because of the new moon, residents were not surprised to see the usual low-lying lanes under water. Nevertheless, this day was different. Pretty much the entire city was covered by the lagoon. People stayed inside to wait out the water, only going outside when they were sure the water was definitely going down. The townspeople went outside to take pictures and explore the current townscape…to see what was underwater now. They were quite surprised at the scene before them.

By mid-afternoon, the water had gone down to more normal levels, but all over the world, the papers made it seem like the whole city was sinking. The high tide would come again on December 2nd, but it was nothing like December 1st. Cleanup was still underway on December 2nd, of course, but most businesses were open again. I suppose that if your city spends it’s life in one stage of flood or another, this extra high tide was just something to be taken in stride. Yes, people were surprised at the higher than normal flood waters from the tide, but they weren’t panicked. It was just another day in the life of Venice.

The ship, SS Daniel J. Morrell was a 603 foot Great Lakes freighter, first launched August 22, 1906. It was operated by Cambria Steamship Company. The freighter was used to carry bulk cargoes such as iron ore. SS Daniel J. Morrell was named for Daniel Johnson Morrell, a Republican member of the US House of Representatives from Pennsylvania. In 1855 he moved to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and became general manager of the Cambria Iron Company, which was the greatest manufacturer of iron and steel in the United States until the Johnstown Flood. As a former general manager of Cambria Steamship Company…Morrell died August 20, 1885…naming the ship after him made sense.

The ship, SS Daniel J. Morrell was a 603 foot Great Lakes freighter, first launched August 22, 1906. It was operated by Cambria Steamship Company. The freighter was used to carry bulk cargoes such as iron ore. SS Daniel J. Morrell was named for Daniel Johnson Morrell, a Republican member of the US House of Representatives from Pennsylvania. In 1855 he moved to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and became general manager of the Cambria Iron Company, which was the greatest manufacturer of iron and steel in the United States until the Johnstown Flood. As a former general manager of Cambria Steamship Company…Morrell died August 20, 1885…naming the ship after him made sense.

SS Daniel J. Morrell, along with her sister ship, SS Edward Y. Townsend were making the last run of the season. On November 29, 1966, they encountered a storm with winds exceeding 70 miles per hour and swells that topped the height of the ship, at 20 to 25 feet. Edward Y. Townsend decided to take shelter in the St. Clair River. That left Daniel J. Morrell alone on the waters north of Pointe Aux Barques, Michigan, heading for the protection of Thunder Bay. As the storm grew worse, and at 2:00pm, the Morrell began to break up, which forced the crew onto the deck. Many of the crew panicked and jumped to their deaths in the 34° Lake Huron waters. At 2:15pm, the ship’s hull broke and allowed water to pour in, and the remaining crewmen loaded into a raft on the bow of the vessel. While they waited for the ship to break up and the raft to be thrown into the lake, there were shouts that a ship had been spotted off the port bow. Unfortunately, moments later, it became clear that  the looming object was not another ship, but Daniel J. Morrell’s aft section, barreling towards them under the power of the ship’s engine. The ship broke apart, throwing the rafts into the water heading into the distance.

the looming object was not another ship, but Daniel J. Morrell’s aft section, barreling towards them under the power of the ship’s engine. The ship broke apart, throwing the rafts into the water heading into the distance.

Tragically, Daniel J. Morrell was not reported missing until 12:15pm the following afternoon, November 30th. By then, the vessel was overdue at her destination, Taconite Harbor, Minnesota. The US Coast Guard issued a “be on the lookout” alert and dispatched several vessels and aircraft to search for the missing freighter. At around 4:00pm on November 30th, a Coast Guard helicopter located the lone survivor, 26-year-old Watchman Dennis Hale, near frozen and floating in a life raft with the bodies of three of his crewmates. Hale had survived the nearly 40 hour ordeal in frigid temperatures wearing only a pair of boxer shorts, a lifejacket, and a pea coat. Since his crewmates had passed away, poor Hale was left alone with his thoughts…trying to avoid thinking about the cold bodies lying next to him. The survey of the wreck found the shipwreck in 220 feet of water with the two sections 5 miles apart.

Lost in the tragic sinking were Norman M. Bragg, Stuart A. Campbell, John J. Cleary Jr, Arthur I. Crawley, George A. Dahl, Larry G. Davis, Arthur S. Fargo, Charles H. Fosbender, Saverio Grippi, John M. Groh (missing),  Nicholas P. Homick, Phillip E. Kapets, Chester Konieczka, Duncan R. MacLeod, Joseph A. Mahsem, Valmour A. Marchildon, Ernest G. Marcotte, Alfred G. Norkunas, David L. Price, Henry Rischmiller, Stanley J. Satlawa (missing), John H. Schmidt, Charles J. Sestakauskas, Wilson E. Simpson, Arthur E. Stojek, Leon R. Truman, Albert P. Wieme, and Donald E. Worcester. The remains of 26 of the 28 lost crewmen were eventually recovered, with most of them found in the days following the sinking. Still, bodies from Daniel J. Morrell continued to be found well into May of the following year. The two men whose bodies were never recovered were declared legally dead in May 1967. The sole survivor of the sinking, Dennis Hale, died of cancer on September 2, 2015, at the age of 75.

Nicholas P. Homick, Phillip E. Kapets, Chester Konieczka, Duncan R. MacLeod, Joseph A. Mahsem, Valmour A. Marchildon, Ernest G. Marcotte, Alfred G. Norkunas, David L. Price, Henry Rischmiller, Stanley J. Satlawa (missing), John H. Schmidt, Charles J. Sestakauskas, Wilson E. Simpson, Arthur E. Stojek, Leon R. Truman, Albert P. Wieme, and Donald E. Worcester. The remains of 26 of the 28 lost crewmen were eventually recovered, with most of them found in the days following the sinking. Still, bodies from Daniel J. Morrell continued to be found well into May of the following year. The two men whose bodies were never recovered were declared legally dead in May 1967. The sole survivor of the sinking, Dennis Hale, died of cancer on September 2, 2015, at the age of 75.

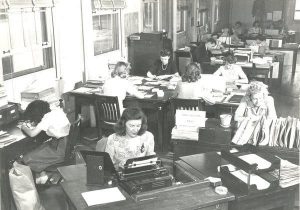

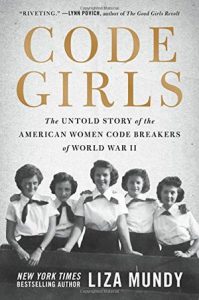

During World War II, when men were in short supply due to deployments, and the secret codes of the Japanese and Germans were causing major problems, the American government was faced with a difficult decision. They needed people who were qualified to break the codes of their enemies, and the only code breakers were in very short supply. The decision was made to search out college-educated women, preferably with degrees in Mathematics, Physics, and those who were fluent in other languages. There weren’t a lot of college educated women in those days, and even fewer with degrees in math or physics, but there were teachers. The Navy and the Army began recruiting these women. The women were required to go through a battery of tests and interviews to see if they had what it took to become code breakers. Many did not, but those who did were offered an exciting, but stressful career.

During World War II, when men were in short supply due to deployments, and the secret codes of the Japanese and Germans were causing major problems, the American government was faced with a difficult decision. They needed people who were qualified to break the codes of their enemies, and the only code breakers were in very short supply. The decision was made to search out college-educated women, preferably with degrees in Mathematics, Physics, and those who were fluent in other languages. There weren’t a lot of college educated women in those days, and even fewer with degrees in math or physics, but there were teachers. The Navy and the Army began recruiting these women. The women were required to go through a battery of tests and interviews to see if they had what it took to become code breakers. Many did not, but those who did were offered an exciting, but stressful career.

Upon arrival in Washington DC, these women found themselves in direct competition with the men, and the men didn’t like it one bit. Nevertheless, the feelings the men had for these women who were a threat to their  job, was at least matched by what the public thought of these women who, sworn to secrecy, had to lie about the work they did. They told people they were secretaries, and glorified waitresses, bring coffee to their bosses, while adding a bit of “interest” to the office. People thought these women were “loose” women…”gold diggers” looking for a husband, and because of the deep need for security, the women were forced to let people think what they wanted too.

job, was at least matched by what the public thought of these women who, sworn to secrecy, had to lie about the work they did. They told people they were secretaries, and glorified waitresses, bring coffee to their bosses, while adding a bit of “interest” to the office. People thought these women were “loose” women…”gold diggers” looking for a husband, and because of the deep need for security, the women were forced to let people think what they wanted too.

No matter what the public thought, these women code breakers were a vital part of the war effort. Our men were dying because we had no idea where the ships and submarines were until they struck. These women turned the tables in favor of the Allies, though few people ever knew it. The women were told they must never speak of what they did there…even after the war, and most of them took their secrets to the grave. While the women were forced to keep their secrets, they all knew that what they were doing mattered. They also knew things about the war, that others didn’t know. They knew the danger the Allied ships were in. They knew about ship that were torpedoed, almost as soon as it happened, and sometimes the ships were ones that friends and loved ones were stationed on…meaning they knew of their loved ones deaths almost immediately after they were killed.

At great sacrifice to themselves, the women code breakers fought a battle in the war that many people never  knew about. The stress, and just the shear gravity of the situation wore of the women. Some later had to seek psychiatric help, and some had nervous breakdowns, still they kept their secrets, lest their services were ever needed again. They kept them in case they ever had to be used again. They kept them because they had orders, and they would follow their orders no matter what. The work had been tedious, and sometimes codes took a long time to crack, but the determined women stuck it out, although most would never be thanked for their hard work. It didn’t matter. Their work was vital, and they were saving lives. That would have to be enough to carry them through the rest of their lives.

knew about. The stress, and just the shear gravity of the situation wore of the women. Some later had to seek psychiatric help, and some had nervous breakdowns, still they kept their secrets, lest their services were ever needed again. They kept them in case they ever had to be used again. They kept them because they had orders, and they would follow their orders no matter what. The work had been tedious, and sometimes codes took a long time to crack, but the determined women stuck it out, although most would never be thanked for their hard work. It didn’t matter. Their work was vital, and they were saving lives. That would have to be enough to carry them through the rest of their lives.

Most people, men anyway, think that it is only women who are fashion conscious to a fault. While many women are very fashion conscious, so are many men, and the fashions that some of the men wore can be just as dangerous. When fashion consists of the wearing of articles of clothing or accessories that have the ability to cause death or injury, we are in danger of sacrificing too much in the name of fashion.

Most people, men anyway, think that it is only women who are fashion conscious to a fault. While many women are very fashion conscious, so are many men, and the fashions that some of the men wore can be just as dangerous. When fashion consists of the wearing of articles of clothing or accessories that have the ability to cause death or injury, we are in danger of sacrificing too much in the name of fashion.

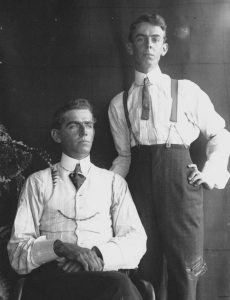

Some fashions do no harm, but looking back on them, we can see just how silly they looked. Nevertheless, powdered wigs were in fashion for men in several different centuries. Long hair was considered a show of status, for both men and women over the years. In ancient Greece, long male hair was a symbol of wealth and power, while a shaven head was appropriate for a slave. The problem occurred when the person, usually the men, but women too, had thinning hair. If their social status depended on that hair, they would need a way to fix the problem when it did not exist. The powdered wig helped with that, and some men wore their wigs in very elaborate styles. In the 1760s, aristocratic British men donned large wigs with a small hat or feather at the top. The young men who took up this fashion trend reportedly brought it back from their “Grand Tour” across Continental Europe in which they intended to “deepen cultural knowledge.” The style is, in fact, named after the Italian pasta dish…macaroni, signifying sophistication and worldliness. It is here that we get the song many of us have wondered about called, “Yankee Doodle,” the lyrics of which pointed out that the feather on top was supposedly called macaroni.

The shoes of the men have taken some strange turns as well. Known as the Poulaine, this super long shoe  reigned supreme with men across Europe in the late 14th century. The shoes, called Crakow were named after Krákow, Poland because they were introduced to England by the Polish nobles. Once the shoes were seen at court, they became all the rage…even though the shoes were six to twenty four inches long. I’m sure you are thinking to yourself, “Who would be crazy enough to wear these?” Well, I’ll tell you that current styles (or maybe just a year or so in the past) saw women, and men too, wearing shoes that had an extra long pointed toe, so it isn’t just an oddity of 14th century Britain. The shoes were a quick indicator of social status…the longer the shoe, the higher the wearer’s station. Some of these shoes were so long that chains were sometimes strung from the toe of the Crakow to the knee to allow the wearer to walk. Other times the toes were stuffed with material for the same reason, making the toes stiff. The strange shoes were considered ridiculous, vain, and dangerous by many conservatives and church leaders, who called them “devil’s fingers.”

reigned supreme with men across Europe in the late 14th century. The shoes, called Crakow were named after Krákow, Poland because they were introduced to England by the Polish nobles. Once the shoes were seen at court, they became all the rage…even though the shoes were six to twenty four inches long. I’m sure you are thinking to yourself, “Who would be crazy enough to wear these?” Well, I’ll tell you that current styles (or maybe just a year or so in the past) saw women, and men too, wearing shoes that had an extra long pointed toe, so it isn’t just an oddity of 14th century Britain. The shoes were a quick indicator of social status…the longer the shoe, the higher the wearer’s station. Some of these shoes were so long that chains were sometimes strung from the toe of the Crakow to the knee to allow the wearer to walk. Other times the toes were stuffed with material for the same reason, making the toes stiff. The strange shoes were considered ridiculous, vain, and dangerous by many conservatives and church leaders, who called them “devil’s fingers.”

In the 19th century, men began wearing detachable collars, that were heavily starched until they were quite stiff. While the collars didn’t look all that odd, they could be deadly. Because they were so heavily starched, taken to the extreme of the collar being nearly unbendable, and because they were attached with a singular or  pair of studs, the collar could slowly asphyxiate a man, if he fell asleep or passed out while drinking. It had a similar effect to a cord being wrapped tightly around the poor man’s neck. Another dangerous aspect of the collar was its pointed corners. A Saint Louis man, wearing one of these collars, tripped in the street and the pointed corners of the collar jabbed into this throat, “making two ugly gashes.” If the gash happened to be in the vicinity of the Jugular vein, death could come quite quickly. These collars were so lethal, in fact, that they were known as “the father killer.” I can only imagine how many women and children pleaded with their husbands or fathers not to wear the collar, which maybe should have been called the choker.

pair of studs, the collar could slowly asphyxiate a man, if he fell asleep or passed out while drinking. It had a similar effect to a cord being wrapped tightly around the poor man’s neck. Another dangerous aspect of the collar was its pointed corners. A Saint Louis man, wearing one of these collars, tripped in the street and the pointed corners of the collar jabbed into this throat, “making two ugly gashes.” If the gash happened to be in the vicinity of the Jugular vein, death could come quite quickly. These collars were so lethal, in fact, that they were known as “the father killer.” I can only imagine how many women and children pleaded with their husbands or fathers not to wear the collar, which maybe should have been called the choker.

I can understand the need of people to have a certain fashion sense, as I am also one who likes to look up to date and to have a good fashion sense too, but people really need to also consider their own safety when it comes to style. It pays to listen to others who might know something about this certain idea of fashion, that could not only benefit you, but possibly save your life.

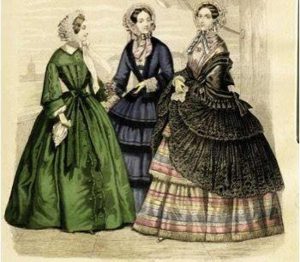

Women have always had an eye for fashion, but I can’t say that having an “eye” for fashion, is the same as having common sense for fashion. In the Victorian era, Bottle-green dresses were all the rage. I understand the love of the color green, and how a beautiful emerald green might be a coveted color. The problem occurs with the process of obtaining that color. The process used to achieve this lovely shade of green involved the fabric being dyed using large amounts of arsenic…yes, rat poison!! Some women suffered nausea, impaired vision, and skin reactions to the dye. They endured the suffering because the dresses were only worn on special occasions, thereby limiting exposure to the arsenic in the fabric. By contrast, it was the garment makers were the real sufferers. Many of them became very ill and even died to bring this trend to the fashionable set.

Women have always had an eye for fashion, but I can’t say that having an “eye” for fashion, is the same as having common sense for fashion. In the Victorian era, Bottle-green dresses were all the rage. I understand the love of the color green, and how a beautiful emerald green might be a coveted color. The problem occurs with the process of obtaining that color. The process used to achieve this lovely shade of green involved the fabric being dyed using large amounts of arsenic…yes, rat poison!! Some women suffered nausea, impaired vision, and skin reactions to the dye. They endured the suffering because the dresses were only worn on special occasions, thereby limiting exposure to the arsenic in the fabric. By contrast, it was the garment makers were the real sufferers. Many of them became very ill and even died to bring this trend to the fashionable set.

Another crazy style was known as Panniers, which comes from the French word “panier,” meaning “basket.” These were popular in the 17th and 18th centuries. The look involved a boxed petticoat to expanded the width of skirts and dresses. The contraption stood out on either side of the waistline…straight out!! Panniers varied in size and were made of whalebone, wood, metal, and sometimes reeds. Extremely large panniers were worn mostly on special occasions and reflected the wearer’s social status. Even the servants wore them, though in a much smaller version. Two women couldn’t walk through an entrance at the same time or sit on a couch together, because their panniers took up an entire extra seat or more. The device was also uncomfortable, limiting movement and activity.

In the 1910s, French designer Paul Poiret, who was well known as “The King of Fashion” in America, debuted the hobble skirt. The long, close-fitting skirts forced women who wore them to adopt mincing, tiny steps. True, Poiret’s design liberated women from heavy petticoats and constricting corsets. But as he said, “Yes, I freed the

bust. But I shackled the legs.” This makes me wonder why women allow their fashion ideas to come from men…who don’t have to wear the clothes they design. Some of these “fashions” were enough to make a woman faint, because her corset was too tight, and she could not get sufficient air.

bust. But I shackled the legs.” This makes me wonder why women allow their fashion ideas to come from men…who don’t have to wear the clothes they design. Some of these “fashions” were enough to make a woman faint, because her corset was too tight, and she could not get sufficient air.

During the Roaring ’20s, women no longer wanted the hourglass shape. Now the style was the boyish flapper figure. Underwear had to change to assist in this new look, and women who were “busty,” had a big problem and the underwear needed a big overhaul. The goal of every undergarment was to flatten the breasts and torso, so that flapper dresses could hang straight down without any curvaceous interruptions. Corset-makers R. and W.H. Symington invented a garment, the Symington Side Lacer, that would flatten the breasts. The wearer would slip the garment over her head and pull the straps and side laces tight to smooth out curves. Other manufacturers designed similar devices. The Miracle Reducing Rubber Brassiere was “scientifically designed without bones or lacings,” while the Bramley Corsele combined the brassiere and corset into one piece that easily layered under dresses. I wonder how anyone could breathe in these prisons known as underwear.

The Crinoline, also known as the hoop skirt, was a bell-shaped device that pushed the volume of skirts to an extreme degree. Worn in the 1800s by Victorian women, Crinolines were originally petticoats made of linen stiffened with horsehair. Wonderful…now we are wearing horsehair under our skirts. This created a big problem. It was just too hot with so many petticoats. Later, the invention of the steel cage crinoline offered the same voluminous look without the extra heat and bulk of thick petticoats. These undergarments were clumsy and hard to control, but they were also dangerous. In 1858, a young woman in Boston died when her large skirt caught embers from a fireplace in her parlor and went up in flames. It all happened to fast to save her. Nineteen such deaths occurred in a two-month period. That is a heavy price to pay in the name of fashion.

And then, there was the “Grecian bend,” the Victorian bustle. It arrived on the scene in the 1870s. The earliest version of this trend simply featured excess fabric gathered and draped at the back of a dress. Eventually, though, skirts were puffed up with large cushions filled with straw. Ladies who wore them ended up with exaggerated figures with outthrust hindquarters. The bustle was frequently a target of ridicule. This style

reminds me of the “padded seat” of modern day leggings, though the modern day version isn’t quite so exaggerated. In 1868, Laura Redden Searing, using the pen name Howard Glyndon, wrote about the agony young women put themselves through for fashion in the New York Times, “If you knew the Spartan courage which is required to go through an ordeal of this sort for two or three hours at a time, you would not wonder that she has not an idea left in her head after her daily display is over,” she said. Hahahaha!! That sounds reasonable to me.

reminds me of the “padded seat” of modern day leggings, though the modern day version isn’t quite so exaggerated. In 1868, Laura Redden Searing, using the pen name Howard Glyndon, wrote about the agony young women put themselves through for fashion in the New York Times, “If you knew the Spartan courage which is required to go through an ordeal of this sort for two or three hours at a time, you would not wonder that she has not an idea left in her head after her daily display is over,” she said. Hahahaha!! That sounds reasonable to me.

Marie Sklodowska was born in an era when women seldom got a very long education, if they got one at all. Born on November 7, 1867 in Warsaw (modern-day Poland). Sklodowska was the youngest of five children, following siblings Zosia, Józef, Bronya and Hela. Their parents were both teachers. Her father, Wladyslaw, was a math and physics instructor. When she was only 10, Sklodowska lost her mother, Bronislawa, to tuberculosis. Sklodowska, being a woman, probably should have grown up to be a wide and mother, dependent on her husband for everything…not that that is a horrible thing, because it isn’t, but it was not all she wanted. She had a good mind for Physics and Chemistry…both subjects were almost unheard of for women in those days.

Marie Sklodowska was born in an era when women seldom got a very long education, if they got one at all. Born on November 7, 1867 in Warsaw (modern-day Poland). Sklodowska was the youngest of five children, following siblings Zosia, Józef, Bronya and Hela. Their parents were both teachers. Her father, Wladyslaw, was a math and physics instructor. When she was only 10, Sklodowska lost her mother, Bronislawa, to tuberculosis. Sklodowska, being a woman, probably should have grown up to be a wide and mother, dependent on her husband for everything…not that that is a horrible thing, because it isn’t, but it was not all she wanted. She had a good mind for Physics and Chemistry…both subjects were almost unheard of for women in those days.

As a child, Sklodowska took after her father. She was bright and curious, and she excelled at school. Still, despite being a top student in her secondary school, she could not attend the men’s-only University of Warsaw. She instead continued her education in Warsaw’s “floating university,” a set of underground, informal classes held in secret. Both Marie and her sister, Bronya dreamed of going abroad to earn an official degree, but they lacked the financial resources to pay for more schooling. Sklodowska would not give up her dream. She worked out a deal with her sister, “She would work to support Bronya while she was in school, and Bronya would return the favor after she completed her studies.”

Sklodowska worked as a tutor and a governess for the next five years. She didn’t want to get behind, so she used her spare time to study…reading about physics, chemistry and math. Then in 1891, Sklodowska finally made her way to Paris and enrolled at the Sorbonne. She threw herself into her studies, but this dedication had a personal cost: with little money, Sklodowska survived on buttered bread and tea. Sometimes, her health suffered because of her poor diet. Nevertheless, Sklodowska completed her master’s degree in physics in 1893 and earned another degree in mathematics the following year.

You might be wondering exactly who Marie Sklodowska was, and why she was important. It might help to know that on July 26, 1895, Marie got married to French physicist, Pierre Curie. They were introduced by a colleague of Marie’s after she graduated from Sorbonne University. Marie had received a commission to perform a study on different types of steel and their magnetic properties and needed a lab for her work. As most people already know, she did her work at a great cost to her own health, but what most people probably don’t know, is that the radiation levels Curie was exposed to were so powerful that her notebooks must now be kept in lead-lined boxes, and it’s not just Curie’s manuscripts that are too dangerous to touch, either. If you visit the Pierre and Marie Curie collection at the Bibliotheque Nationale in France, many of her personal possessions…from her furniture to her cookbooks…require protective clothing to be safely handled. You’ll also have to sign a liability waiver, just in case.

In those days, things like radiation and it’s dangers were not known. Marie Curie was basically walking around with bottles of polonium and radium, both highly radioactive compounds, in her pockets all the time. She even kept capsules full of the dangerous chemicals on her shelf. “One of our joys was to go into our workroom at night; we then perceived on all sides the feebly luminous silhouettes of the bottles of capsules containing our products,” Marie, the Nobel Prize-winning scientist wrote in her autobiography. “It was really a lovely sight and one always new to us. The glowing tubes looked like faint, fairy lights.” In case you didn’t know, Marie Curie discovered radioactivity. Also, along with her husband, Pierre, they discovered the radioactive elements, Polonium and Radium, while working with the mineral, Pitchblende…a form of the mineral Uraninite occurring in  brown or black masses and containing radium. She also championed the development of X-rays, following her husband’s death in a street accident in Paris on 19 April 1906.

brown or black masses and containing radium. She also championed the development of X-rays, following her husband’s death in a street accident in Paris on 19 April 1906.

The fact that the notebook and related paraphernalia are still radioactive a century later is not as well known. The most common isotope of radium, the deadly chemical Curie carried in her pockets, has a half-life of 1,601 years. That said, people will not be able to go digging through the Curie’s library any time in this century, either. It is also known now, but wasn’t then, that the chemicals would end Curie’s life at a fairly early age. Curie died on July 4, 1934, of aplastic anemia, believed to be caused by prolonged exposure to radiation. She was 58 years old.

Strange things have been known to happen over the centuries of Earth’s existence. Most end up being clearly explained. Some are explained, but few people believe the explanation, and still others are forever mysteries…destined to have no possible explanation. People, especially those who witness the event, just know that it did happen. Often, wars are filled with strange stories. Everything from bombs killing everyone in an area, except for one lone old woman; to enemy soldiers allowing a soldier to go free, even though the enemy clearly had the upper hand. Of course, some mysteries defy any possible explanation. Such is the case of the Phantom Fortress. If one looks there can be found all manner of oddities and anomalies scattered in the background of the more sensational news of the fighting of a war, coming from land, air, and sea. From ghost ships found floating in the oceans years after they were last seen, their crews mysteriously missing, with no sign of violence or death on board. Of course, the stories run wild, sighting every possibility from UFOs; to disappearance to another dimension; to desertion, though hard to explain, when no trace of the crew ever showed up anywhere else. Still, few were more strange than the Phantom Fortress.

Strange things have been known to happen over the centuries of Earth’s existence. Most end up being clearly explained. Some are explained, but few people believe the explanation, and still others are forever mysteries…destined to have no possible explanation. People, especially those who witness the event, just know that it did happen. Often, wars are filled with strange stories. Everything from bombs killing everyone in an area, except for one lone old woman; to enemy soldiers allowing a soldier to go free, even though the enemy clearly had the upper hand. Of course, some mysteries defy any possible explanation. Such is the case of the Phantom Fortress. If one looks there can be found all manner of oddities and anomalies scattered in the background of the more sensational news of the fighting of a war, coming from land, air, and sea. From ghost ships found floating in the oceans years after they were last seen, their crews mysteriously missing, with no sign of violence or death on board. Of course, the stories run wild, sighting every possibility from UFOs; to disappearance to another dimension; to desertion, though hard to explain, when no trace of the crew ever showed up anywhere else. Still, few were more strange than the Phantom Fortress.

On November 23, 1944, a British Royal Air Force anti-aircraft unit stationed near Cortonburg, Belgium was suddenly surprised to see an American Army Air Corps B-17 bomber, nicknamed the “Flying Fortress,” heading in their direction. Because there was no such landing scheduled and because of the speed of the incoming aircraft it was assumed that it was preparing to make an emergency landing at the base. Still, after checking with the base tower, it was confirmed that that no such B-17 landing was expected. Be that as it may, this plane was coming in for a landing, so the gunner crew watched helplessly as the massive aircraft came hurtling in towards a nearby open, plowed field.

No matter what standards you use, this landing was a messy one to say the least. The plane bounced and swerved along as the terrified gunners looked on. It finally came to a stop dangerously close to their position after one of its wings clipped the ground. Nevertheless, it was still in one piece and had not actually crashed, but it was an incredibly rough landing. The stunned gunners watched as the aircraft sat there looming over the field, its propellers continuing to spin. The minutes ticked by, but no one exited the plane. After waiting 20 minutes with no sign of human activity, and the plane just sitting there with its engines running, the gunner crew decided to go in and investigate. They had no idea what kind of a scene awaited them inside, but what they found, they never could have guessed. Upon opening the entry hatch under the fuselage, they entered. The gunner crew expected that the crew had been injured or was otherwise unable to get out of the plane, but what they found was that the plane was completely empty. Unable to believe what they had just witnessed, especially in light of the empty plane, the gunner crew made a full sweep through the aircraft. The gunner crew reported that it looked like the crew had just recently been there and must have left the aircraft in a hurry. They found chocolate bars unwrapped and half eaten lying about, a row of neatly folded parachutes, with none apparently missing, and jackets that had been neatly hung up.

The superior officer, a John V. Crisp, would say of the eerie scene, “We now made a thorough search and our most remarkable find in the fuselage was about a dozen parachutes neatly wrapped and ready for clipping on. This made the whereabouts of the crew even more mysterious. The Sperry bomb-sight remained in the Perspex nose, quite undamaged, with its cover neatly folded beside it. Back on the navigator’s desk was the code book giving the colours and letters of the day for identification purposes. Various fur-lined flying jackets lay in the fuselage together with a few bars of chocolate, partly consumed in some cases.” Crisp found himself in an awkward position. He knew what he was seeing. He knew that he would have to write up the report on the incident. And most importantly, he knew that his men were looking to him for answers. Where had the crew of the “Phantom Fortress” gone and how had the plane landed on its own? This was not during a time when planes could be programed to land. No one had any idea how this could have come to pass. Crisp told the men to shut the engines down, and they inspected the planes interior further. The men looked for anything that might provide answers. The log book was found opened, and the last cryptic words written in it were “bad flak.” Yet, all of the parachutes seemed to be accounted for and the exterior of the plane did not have evidence of flak damage, or any damage except for what it had incurred in its rough landing, such as the buckled wing and one disabled engine. The log entry just seemed strange considering.

The B-17’s crew was eventually found, alive and well. For their side, they said, “They changed their course towards Brussels, Belgium, at the same time making the plane lighter by dumping and jettisoning any unnecessary or nonessential equipment on board. When the plane still continued to suffer and a second engine on the struggling plane sputtered out, it was decided that the aircraft would be unable to make the journey, and the crew had then decided to bail out. The B-17 was put on autopilot and left to its fate as the crew jumped to safety. No one thought it would make it very far, let alone somehow land, but land it did.” It seemed as if they honestly thought they had been in battle, and even more, that they had bailed out, with parachutes that were miraculously replaced. Still, why did ground crew report all 4 engines working as the bomber had approached, with one being damaged only upon landing, when the report said that 2 engines had been knocked out during the mission? Where was the damage from the claimed enemy fire? Perhaps most mysterious of all, how had a large, cumbersome plane like the B-17 manage to come to a landing without a pilot?

Authorities on the case, as well as crew members of the Phantom Fortress, suggested some theories to explain the mysteries surrounding the event. For instance, with the engines it could have been that the technical difficulties cleared up on their own after the crew had bailed out, making the plane seem to have 4 fully operating engines on approach, although why they would start working again after being taken out remains mysterious. If the engines had been in bad enough shape for the crew to abandon the aircraft it seems odd that they should kick back into working order on their own and continue whirring away even after the rough landing. As to the lack of any apparent visible damage from enemy fire, the gunner crew could have simply missed the damage due to the untrained eyes of the team that initially investigated the plane after it had landed. They were just a gunner crew, not trained aviators, and may have mistaken the damage reported by the B-17 crew as being from the crash. They might not have noticed that the aircraft had sustained battle damage, but then again they were anti-aircraft gunners and might have had some idea. With the parachutes, it was surmised that they had possibly mistaken some spare parachutes as the full compliment. However, this is all speculation, and the mystery has never been totally solved. Still, the biggest mystery simply cannot be explained away. How did the B-17 come to a landing mostly intact without a pilot? Autopilot is one thing, but landing is another beast altogether. As the saying goes, “Flying is easy, landing is hard.” A pilotless B-17 landing by itself with no one on board was unprecedented. It should have careened into the ground to crash into a ball of fire and debris, or at least ended up a heap of twisted wreckage. So how could this happen?

Although no one really knows for sure, the main theory is “that the plane simply lost altitude slowly, at just the right speed, and with just the right angle of descent to come down relatively softly enough to appear as if it was landing, with the B-17’s legendary toughness and sturdy frame managing to hold it together to keep it from disintegrating.” To this, I say, “Come on!! Get serious!!” The odds of all of this happening in just such a way is all but impossible. Also, there is the rather odd detail that this unmanned plane just happened to come  down in the exact best place to land under the circumstances, in that wide open field, and not one of the countless other places it could have come down more tragically. Its just too odd. Nevertheless, the mystery landing of the “Phantom Fortress” did happen. The details of how it did remain mysterious and open to speculation. What we do know for sure is that this B-17 was on a bombing mission in Germany, that it did land without a crew in that field, and that the crew members were later found to have been alive and well with quite a story to tell.

down in the exact best place to land under the circumstances, in that wide open field, and not one of the countless other places it could have come down more tragically. Its just too odd. Nevertheless, the mystery landing of the “Phantom Fortress” did happen. The details of how it did remain mysterious and open to speculation. What we do know for sure is that this B-17 was on a bombing mission in Germany, that it did land without a crew in that field, and that the crew members were later found to have been alive and well with quite a story to tell.

When we think of movie stars, we seldom think of them as soldiers, even if they have played a soldier on television or the movies. Nevertheless, many have served. One of my favorite shows as a kid was McHale’s Navy. McHale was played by Ernest Borgnine, who was born Ermes Effron Borgnino on January 24, 1917, in Hamden, Connecticut. Borgnine was the son of Italian immigrants. His mother, Anna (née Boselli; 1894–c. 1949), was from Carpi, near Modena. His father Camillo Borgnino (1891–1975) was a native of Ottiglio near Alessandria.

When we think of movie stars, we seldom think of them as soldiers, even if they have played a soldier on television or the movies. Nevertheless, many have served. One of my favorite shows as a kid was McHale’s Navy. McHale was played by Ernest Borgnine, who was born Ermes Effron Borgnino on January 24, 1917, in Hamden, Connecticut. Borgnine was the son of Italian immigrants. His mother, Anna (née Boselli; 1894–c. 1949), was from Carpi, near Modena. His father Camillo Borgnino (1891–1975) was a native of Ottiglio near Alessandria.

Borgnine had a normal childhood, and after high school, he enlisted in the United States Navy in October 1935. He served aboard the destroyer/minesweeper USS Lamberton and was honorably discharged from the Navy in October 1941. Then, the  attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1942, changed many things. In January 1942, Borgnine re-enlisted in the Navy. During World War II, he patrolled the Atlantic Coast on an antisubmarine warfare ship, the USS Sylph. In September 1945, he was honorably discharged from the Navy. With the two stints, Borgnine served a total of almost ten years in the Navy and obtained the grade of gunner’s mate 1st class. His military awards include the Navy Good Conduct Medal, American Defense Service Medal with Fleet Clasp, American Campaign Medal with ?3?16″ bronze star, and the World War II Victory Medal. Who knew?

attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1942, changed many things. In January 1942, Borgnine re-enlisted in the Navy. During World War II, he patrolled the Atlantic Coast on an antisubmarine warfare ship, the USS Sylph. In September 1945, he was honorably discharged from the Navy. With the two stints, Borgnine served a total of almost ten years in the Navy and obtained the grade of gunner’s mate 1st class. His military awards include the Navy Good Conduct Medal, American Defense Service Medal with Fleet Clasp, American Campaign Medal with ?3?16″ bronze star, and the World War II Victory Medal. Who knew?

To me, it seems like all this also prepared him for his most famous television show. As a veteran sailor, he knew how things were run on a ship. Of course, how much of his knowledge could be used on the show depends on the directors. If they had any good sense, they would have used his knowledge, and made the show more realistic. Still, as a kid, I doubt if I would know if it was realistic or not, and after all these years, I can’t say I would recall any of the details. Nor would I know if they were realistic or not. Nevertheless, I always liked the show, and I really liked Ernest Borgnine. I just never knew that he had been a sailor during World War II, or that he had played a part in locating and sinking submarines. I also didn’t realize that he enlisted not once, but twice, or that he served a total of ten years. Years later, on July 8, 2012, after many years as a successful actor, Ernest Borgnine died of kidney failure on July 8, 2012 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. He was 95 years old.

To me, it seems like all this also prepared him for his most famous television show. As a veteran sailor, he knew how things were run on a ship. Of course, how much of his knowledge could be used on the show depends on the directors. If they had any good sense, they would have used his knowledge, and made the show more realistic. Still, as a kid, I doubt if I would know if it was realistic or not, and after all these years, I can’t say I would recall any of the details. Nor would I know if they were realistic or not. Nevertheless, I always liked the show, and I really liked Ernest Borgnine. I just never knew that he had been a sailor during World War II, or that he had played a part in locating and sinking submarines. I also didn’t realize that he enlisted not once, but twice, or that he served a total of ten years. Years later, on July 8, 2012, after many years as a successful actor, Ernest Borgnine died of kidney failure on July 8, 2012 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. He was 95 years old.

Whenever disaster strikes, the inevitable souvenir hunters seem to come out of the woodwork. It doesn’t matter that someone, or maybe many someones have died in the tragedy. Souvenir hunters think only of themselves, and the stories they can tell, complete with their “precious” souvenir to back up their story. The whole thing makes decent people nauseous.

Whenever disaster strikes, the inevitable souvenir hunters seem to come out of the woodwork. It doesn’t matter that someone, or maybe many someones have died in the tragedy. Souvenir hunters think only of themselves, and the stories they can tell, complete with their “precious” souvenir to back up their story. The whole thing makes decent people nauseous.

On November 17, 1910, famous aviator and stunt pilot, Ralph Johnstone was performing in an air show in Denver, Colorado, when tragedy struck. Johnstone knew the risks of his occupation, and I suppose that he knew that one day, his “number” would come up. Still, you never really believe that it will happen to you, do you? Johnstone was the holder of the World Altitude Record, and the crowds were never disappointed with the show he gave them. That day, at Overland Park would be no exception.

Johnstone flew a Wright Biplane, and he was knows for his many spiral glides, which had made the Wright aviators famous. Johnstone had won many prizes, and on two occasions had expressed the belief that he would be the first to do real fancy work in the sky…and become in a word, the aviating gymnast and loop an imaginary loop. In the day’s first flight, when he was in the air with his friends, Walter Brookins and Archibald Hoxsey. Johnstone had gone through his usual program of dips and glides, and the plane had perfect control, with no indication of structural problems.

On his second flight, Johnstone rose again, and after a few circuits of the course to gain height headed toward the foothills. “Still ascending, he swept back in a big circle, and as he reached the north end of the enclosure, he started his spiral glide. He was then at an altitude of about 800 feet. With his plane tilted at an angle of  almost 90 degrees, he swooped down in a narrow circle, the airplane seeming to turn almost in its own length. As he started the second circle, the middle spur, which braces the left side of the lower plane, gave way, and the wing tips of both upper and lower planes folded up as though they had been hinged. For a second, Johnstone attempted to right the plane by warping the other wing up. Then the horrified spectators saw the plane swerve like a wounded bird and plunged straight toward the earth.”

almost 90 degrees, he swooped down in a narrow circle, the airplane seeming to turn almost in its own length. As he started the second circle, the middle spur, which braces the left side of the lower plane, gave way, and the wing tips of both upper and lower planes folded up as though they had been hinged. For a second, Johnstone attempted to right the plane by warping the other wing up. Then the horrified spectators saw the plane swerve like a wounded bird and plunged straight toward the earth.”

Witnesses said that “Johnstone was thrown from his seat as the nose of the plane swung downward. He caught on one of the wire stays between the plane and grasped one of the wooden braces of the upper plane with both hands. Then, working with hands and feet, he fought by main strength to warp the planes so that their surfaces might catch the air and check his descent. For a second it seemed that he might succeed, for the football helmet the wore blew off and fell much more rapidly than the plane.”

With one wing of his machine crumbled like a piece of paper, Ralph Johnstone, dropped like a rock from a height of 500 feet into the enclosure at Overland Park aviation field and was instantly killed…nearly every bone in his body was broken. That was when the spectators turned “souvenir hunters.” Scarcely had Johnstone hit the ground before morbid men and women swarmed over the wreckage, fighting with each other for souvenirs.  One of the broken wooden stays had gone almost through Johnstone’s body. Before doctors or police could reach the scene, one man had torn this splinter from the body and run away, carrying his “trophy” with Johnstone’s blood still dripping from it. The crowd tore away the canvas from over the body, and even fought for the gloves that had protected his hands from the cold. The scene was utterly disgusting.

One of the broken wooden stays had gone almost through Johnstone’s body. Before doctors or police could reach the scene, one man had torn this splinter from the body and run away, carrying his “trophy” with Johnstone’s blood still dripping from it. The crowd tore away the canvas from over the body, and even fought for the gloves that had protected his hands from the cold. The scene was utterly disgusting.

Johnstone had attempted to cheat death once too often, but “he played the game to the end, fighting coolly and grimly to the last second to regain control of his broken machine.” Fresh from his triumphs at Belmont Park, where he had broken the world’s record for altitude with a flight of 9,714 feet, Johnstone attempted to give the thousands of spectators an extra thrill with his most daring feat, the spiral glide, which had made the Wright aviators famous. The spectators got their thrill, but it cost Johnstone his life.

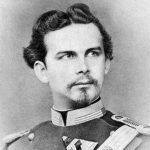

King Ludwig II, who became king of Bavaria at the young age of 19, in 1864, had what many might consider to be a strange obsession…castles. Of course, for a king to love palaces isn’t totally crazy, but he actually took it to another level, and one that many of us can see to this day. I think I can understand his obsession with castles. Though I have never been in one, I have taken virtual tours of several, and they are beautiful.

King Ludwig II, who became king of Bavaria at the young age of 19, in 1864, had what many might consider to be a strange obsession…castles. Of course, for a king to love palaces isn’t totally crazy, but he actually took it to another level, and one that many of us can see to this day. I think I can understand his obsession with castles. Though I have never been in one, I have taken virtual tours of several, and they are beautiful.

Ludwig was a strange king, I suppose, but while castles should have been rather common things to him, he found them to be fascinating. It’s possible that his obsession began in the breathtaking Hohenschwangau Castle, where he grew up. It seems rather strange for a king, or prince, to really take much notice of such places, but maybe King Ludwig II was as much an architect as he was a king. The Hohenschwangau Castle was originally built in the 12th century, but was destroyed by Napoleon. Ludwig’s father had the castle rebuilt, and it currently looks just like it did in 1836. Maybe young King Ludwig II’s infatuation with castes began as he heard the stories about his home being destroyed and rebuilt.

It is thought that his fascination really began to grow when he took a trip to France and saw the Palace of Versailles and Chateau de Pierrefonds. He returned to Bavaria intent on building a culture there like that of France. Of course, building castles is an expensive venture, and King Ludwig II is said to have neglected his duties as king to follow this new passion, and in so doing, he “racked up” a debt of nearly 14 million marks. I’m sure his people weren’t very happy with him, but as we of the more “touristy” persuasion would have to agree, the castles he created were magnificent.

Among the greatest of his castles are Neuschwanstein and Linderhof. From his bedroom in Hohenschwangau, Ludwig trained a telescope on a ridge to keep an eye on Neuschwanstein as it was being constructed. It is said

that Neuschwanstein is the castle that inspired Walt Disney when he created the well-known castle of Disneyland fame. Ludwig’s extravagance and romanticism earned him the nickname of “Mad” King Ludwig. Nevertheless, with their towering turrets in a striking setting, these castles are a huge hit with sightseers. Every tour bus in Bavaria converges on Neuschwanstein and Hohenschwangau, while more tourists flush in each morning by train from Munich, two hours away. Ludwig also commissioned the building of Herrenchiemsee (a partial replica of the Palace of Versailles) and a castle of Falkenstein, but these were never completed.

that Neuschwanstein is the castle that inspired Walt Disney when he created the well-known castle of Disneyland fame. Ludwig’s extravagance and romanticism earned him the nickname of “Mad” King Ludwig. Nevertheless, with their towering turrets in a striking setting, these castles are a huge hit with sightseers. Every tour bus in Bavaria converges on Neuschwanstein and Hohenschwangau, while more tourists flush in each morning by train from Munich, two hours away. Ludwig also commissioned the building of Herrenchiemsee (a partial replica of the Palace of Versailles) and a castle of Falkenstein, but these were never completed.

The homiest of Ludwig’s castles is the small and comfortably exquisite Linderhof, set in the woods 15 minutes from Oberammergau, the Shirley Temple of Bavarian villages (a 45-minute drive from Hohenschwangau). Surrounded by fountains and sculpted, Italian-style gardens, it inspires a feeling of palace envy. Ludwig lived much of his last eight years at Linderhof. He was frustrated by the limits of being a constitutional monarch, so he retreated there. At Linderhof, he was able to live in a private fantasy world where his lavishness glorified his otherwise weakened kingship. He lived as a royal hermit, his dinner table…pre-set with dishes and food…rose from the kitchen below into his dining room so he could eat alone. Beyond the palace is Ludwig’s grotto, a private theater for the reclusive king to enjoy his beloved Wagnerian operas, Here he was usually the sole member of the audience. The grotto features a waterfall, fake stalactites, and a swan boat floating on an artificial lake. The first electricity in Bavaria was generated here, to change the colors of the stage lights and to power Ludwig’s fountain and wave machine.

Ludwig was king for 23 years. In 1886, being fed up with his extravagances, royal commissioners declared him mentally unfit to rule Bavaria. Days later, he was found dead in a lake. People still debate whether it was murder or suicide. But no one complains anymore about the cost of Ludwig’s castles. Within six weeks of his funeral, tourists were paying to see the castles…and they’re still coming.

Ludwig was king for 23 years. In 1886, being fed up with his extravagances, royal commissioners declared him mentally unfit to rule Bavaria. Days later, he was found dead in a lake. People still debate whether it was murder or suicide. But no one complains anymore about the cost of Ludwig’s castles. Within six weeks of his funeral, tourists were paying to see the castles…and they’re still coming.