History

Each American presidency is marked by a defining moment, an event that encapsulates its tenure. For John F. Kennedy’s presidency, the Cuban Missile Crisis stood as that pivotal event. The most intense phase of the crisis, often referred to as the “13 Days,” spanned from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy was informed of the Soviet missile sites being built in Cuba, to October 28, 1962, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev declared the dismantling of the missiles. On October 22, 1962, when it came time to tell the American people about the situation, President Kennedy revealed in a televised address of profound significance, that American spy planes had detected Soviet missile bases in Cuba. This represented a very dangerous situation for the United States. The missile sites were still under construction, but they were close to completion, and they contained medium-range missiles with the capacity to hit several major US cities, including Washington DC.

Each American presidency is marked by a defining moment, an event that encapsulates its tenure. For John F. Kennedy’s presidency, the Cuban Missile Crisis stood as that pivotal event. The most intense phase of the crisis, often referred to as the “13 Days,” spanned from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy was informed of the Soviet missile sites being built in Cuba, to October 28, 1962, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev declared the dismantling of the missiles. On October 22, 1962, when it came time to tell the American people about the situation, President Kennedy revealed in a televised address of profound significance, that American spy planes had detected Soviet missile bases in Cuba. This represented a very dangerous situation for the United States. The missile sites were still under construction, but they were close to completion, and they contained medium-range missiles with the capacity to hit several major US cities, including Washington DC.

Kennedy declared he was imposing a naval “quarantine” on Cuba to block Soviet ships from delivering additional offensive weapons to the island. He stated that the United States would not accept the current missile sites’ presence. The president emphasized that America was prepared to take military action to eliminate what he described as a “secretive, irresponsible, and provocative threat to global peace.”

The Cuban Missile Crisis, as it became known, began on October 14, 1962, when US intelligence, analyzing data from a U-2 spy plane, discovered that the Soviet Union was constructing medium-range missile sites in Cuba. The following day, President Kennedy convened a secret emergency meeting with his top military, political, and diplomatic advisers to address the grave situation. This group came to be known as ExComm, an abbreviation for Executive Committee. Opting against a surgical air strike on the missile sites, ExComm instead chose a naval blockade and demanded the dismantling and removal of the missiles. It was then, on the evening of October 22, that President Kennedy disclosed his decision on national television. Tensions continued to mount over the ensuing six days, to a critical point, and placing the world on the edge of nuclear warfare between the two superpowers.

On October 23, the United States initiated a naval “quarantine” of Cuba. However, President Kennedy opted to allow Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev additional time to contemplate the US maneuver by moving the quarantine line back 500 miles. By October 24, Soviet vessels bound for Cuba, capable of transporting military cargo, seemed to have decelerated, changed course, or turned around as they neared the quarantine zone, except for one ship…the tanker Bucharest. Following appeals from over 40 nonaligned countries, UN Secretary-General U Thant made private overtures to Kennedy and Khrushchev, imploring their administrations to “avoid any actions that might worsen the situation and pose a risk of war.” Under orders from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, United States armed forces escalated to DEFCON 2, the most critical military readiness level ever achieved in the postwar period, while commanders readied for an all-out conflict with the Soviet Union.

On October 25, the aircraft carrier USS Essex and the destroyer USS Gearing tried to intercept the Soviet tanker Bucharest as it breached the US quarantine of Cuba. The Soviet vessel did not comply, but the US Navy refrained from taking it by force, judging that it was unlikely to be carrying offensive weapons. On October 26, Kennedy was informed that construction on the missile bases continued unabated, and ExComm contemplated a US invasion of Cuba. The Soviets apparently felt the tension of their actions, because on that same day, they offered a deal to resolve the crisis: they would dismantle the missile bases in return for a United States guarantee not to invade Cuba.

The following day, Khrushchev escalated the situation by publicly demanding the removal of US missile bases in Turkey, influenced by Soviet military leaders. As Kennedy and his advisors deliberated over this perilous shift in negotiations, a U-2 spy plane was downed over Cuba, resulting in the death of its pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson. It looked like thing might have reached the boiling point, but despite the Pentagon’s dismay, Kennedy prohibited any military response unless further surveillance aircraft were targeted over Cuba. To alleviate the intensifying crisis, Kennedy and his team decided to dismantle the US missile installations in Turkey at a subsequent time, to avoid provoking Turkey, who was an essential NATO ally.

On October 28, Khrushchev declared his government’s decision to dismantle and remove all offensive Soviet weapons from Cuba. Following the broadcast of this public announcement on Radio Moscow, the USSR affirmed its readiness to adopt the resolution secretly suggested by the Americans the previous day. That afternoon, Soviet technicians started dismantling the missile sites, averting the imminent threat of nuclear war. The Cuban Missile Crisis had effectively ended. In November, Kennedy lifted the blockade, and by year’s end, all offensive missiles were removed from Cuba. Later, the United States discreetly withdrew its missiles from Turkey.

At the time, the Cuban Missile Crisis appeared to be a definitive triumph for the United States. In this, Cuba gained a heightened sense of security following the crisis. The withdrawal of obsolete Jupiter missiles from Turkey did not negatively impact the United States’ nuclear strategy. Nevertheless, the crisis spurred the USSR, feeling humiliated, to initiate a substantial nuclear arms expansion. By the 1970s, the Soviet Union had achieved nuclear parity with the United States and developed intercontinental ballistic missiles with the capability to target any city within the United States.

The presidents that followed Kennedy upheld his promise to refrain from invading Cuba, and the relationship with the communist nation, located a mere 80 miles off the coast of Florida, continued to challenge United States foreign policy for over half a century. Finally, in 2015, representatives from both countries declared the official normalization of United States-Cuba relations, encompassing the relaxation of travel bans and the establishment of embassies and diplomatic offices in each nation.

For Kennedy, this pivotal moment in his administration showcased his ability to manage a high-stakes international crisis. His decision to implement a naval blockade and negotiate with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev helped avoid a potential nuclear war. It also demonstrated his leadership and diplomatic skills, as he balanced military readiness with diplomatic negotiations, which ultimately led to the removal of Soviet missiles from Cuba. The successful resolution of the crisis significantly boosted Kennedy’s public image, portraying him as a strong and capable leader who could protect the United States from external threats. The crisis was a defining moment in the Cold War, highlighting the intense rivalry between the United States and the

Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it also led to the establishment of a direct communication line between Washington and Moscow, known as the “hotline,” to prevent future crises. In summary, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a defining event that not only tested Kennedy’s presidency, but it also shaped his legacy as a leader who could navigate the complexities of international relations during one of the most dangerous periods of the Cold War.

Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it also led to the establishment of a direct communication line between Washington and Moscow, known as the “hotline,” to prevent future crises. In summary, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a defining event that not only tested Kennedy’s presidency, but it also shaped his legacy as a leader who could navigate the complexities of international relations during one of the most dangerous periods of the Cold War.

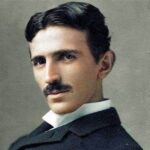

Sometimes, in the minds of geniuses, ideas can become lost or even stolen when the genius lacks the patience to promote their inventions to the world. They have innovated minds, but the marketing, patents, and mass-producing part is boring to them. Nikola Tesla, who was born on July 10, 1856, was such a scientist. Tesla was of Serbian nationality in Smiljan, within the Austrian Empire. He was considered one of the greatest and most enigmatic contributors to the development of electromagnetism and various scientific advancements of his era. Despite his impressive array of patents and discoveries, his contributions were frequently overshadowed during his life.

Sometimes, in the minds of geniuses, ideas can become lost or even stolen when the genius lacks the patience to promote their inventions to the world. They have innovated minds, but the marketing, patents, and mass-producing part is boring to them. Nikola Tesla, who was born on July 10, 1856, was such a scientist. Tesla was of Serbian nationality in Smiljan, within the Austrian Empire. He was considered one of the greatest and most enigmatic contributors to the development of electromagnetism and various scientific advancements of his era. Despite his impressive array of patents and discoveries, his contributions were frequently overshadowed during his life.

Nikola Tesla, a gifted student, attended the Austrian Polytechnic in Graz in 1875. He later moved to secure a job in Marburg, Slovenia. His challenging disposition occasionally surfaced, leading to a falling out with his family and a subsequent nervous breakdown. It is said that Tesla had an IQ of somewhere between 160 and 310 or “off the charts.” That makes it entirely possible that Tesla suffered with many mood swings. After leaving Slovenia, he registered at Charles Ferdinand University in Prague, only to leave once more without finishing his degree.

In his early years, he went through numerous bouts of sickness and bursts of striking inspiration. He frequently had visions of mechanical and theoretical inventions, often accompanied by intense flashes of light. His ability to visualize images in his mind was extraordinary. Instead of drafting plans or scale drawings for his projects, he depended on the vivid images in his imagination.

In 1880, he relocated to Budapest to work for a telegraph company. It was there that he familiarized himself  with twin turbines and contributed to the development of a device that amplified telephone signals. In 1882, he transferred to Paris to join the Continental Edison Company. During his tenure, he enhanced several Edison devices and devised the induction motor and other apparatuses utilizing rotating magnetic fields. Then, armed with a strong recommendation letter, Tesla arrived in the United States in 1884 to join the Edison Machine Works. There, he quickly rose to become a chief engineer and designer. Tasked with enhancing the direct current generators’ electrical system, Tesla was allegedly promised $50,000 for significant improvements. Despite fulfilling his task, Tesla was apparently not compensated, fueling a profound rivalry and resentment towards Thomas Edison. This animosity became a hallmark of Tesla’s life, affecting his financial standing and reputation. The intense feud is also cited as a contributing factor to why neither Tesla nor Edison received the Nobel Prize for their contributions to electrical engineering.

with twin turbines and contributed to the development of a device that amplified telephone signals. In 1882, he transferred to Paris to join the Continental Edison Company. During his tenure, he enhanced several Edison devices and devised the induction motor and other apparatuses utilizing rotating magnetic fields. Then, armed with a strong recommendation letter, Tesla arrived in the United States in 1884 to join the Edison Machine Works. There, he quickly rose to become a chief engineer and designer. Tasked with enhancing the direct current generators’ electrical system, Tesla was allegedly promised $50,000 for significant improvements. Despite fulfilling his task, Tesla was apparently not compensated, fueling a profound rivalry and resentment towards Thomas Edison. This animosity became a hallmark of Tesla’s life, affecting his financial standing and reputation. The intense feud is also cited as a contributing factor to why neither Tesla nor Edison received the Nobel Prize for their contributions to electrical engineering.

Disappointed by the lack of a pay raise, Tesla resigned and briefly worked digging ditches for the Edison telephone company. In 1886, he established his own company, which failed due to his investors’ lack of faith in alternating current (AC). The following year, Tesla experimented with a type of X-Ray technology, managing to photograph the bones in his hand and recognizing the harmful side-effects of radiation. Despite this, his work received minimal attention, and much of his research was destroyed in a fire at a New York warehouse.

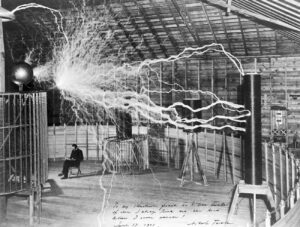

Nikola Tesla was renowned for his intense work ethic and dedication to his work. He often dined alone and  seldom slept, sometimes only two hours per day. He never married, believing that his celibacy was beneficial to his scientific pursuits. In his later years, he adopted a vegetarian diet, subsisting solely on milk, bread, honey, and vegetable juices. In his lifetime, Tesla can be credited with many inventions, among them, the Tesla coil: A system for wireless transmission of electricity; the Tesla turbine: A type of turbine; the radio: Tesla demonstrated radio communication before Marconi; the Magnifying transmitter: A device for wireless energy transmission; and the Induction motor: A key component in modern devices. Tesla died on January 7, 1943, in a hotel room in New York City at the age of 86. After his death, in 1960 the General Conference on Weights and Measures named the SI unit of magnetic field strength the Tesla in his honor.

seldom slept, sometimes only two hours per day. He never married, believing that his celibacy was beneficial to his scientific pursuits. In his later years, he adopted a vegetarian diet, subsisting solely on milk, bread, honey, and vegetable juices. In his lifetime, Tesla can be credited with many inventions, among them, the Tesla coil: A system for wireless transmission of electricity; the Tesla turbine: A type of turbine; the radio: Tesla demonstrated radio communication before Marconi; the Magnifying transmitter: A device for wireless energy transmission; and the Induction motor: A key component in modern devices. Tesla died on January 7, 1943, in a hotel room in New York City at the age of 86. After his death, in 1960 the General Conference on Weights and Measures named the SI unit of magnetic field strength the Tesla in his honor.

There are phenomena that sometimes manifest in the sky seem supernatural, although scientists often have other explanations. I rather think they are supernatural…as in coming from God. Such occurrences were first reported by mountain climbers before the era when airplane travel was common. I’m sure they still see them today too. Climbers would reach a mountain’s summit and suddenly see what seemed to be a figure standing in the distance. I must admit that such a sight would be a little disconcerting, but I wouldn’t mind seeing one. In the mid-1700s, members of a French scientific expedition ascended Pambamarca, a mountain in Ecuador. It seemed like a normal ascent, but when they reached its peak, they witnessed the sun breaking through the clouds, casting their shadows and encircling their heads with halo-like rings. Maybe that is how it happens, but I would say that the conditions would have to be exactly right for this to happen, and I think that is God. I can only imagine their thoughts at that moment…probably fear mixed with curiosity.

There are phenomena that sometimes manifest in the sky seem supernatural, although scientists often have other explanations. I rather think they are supernatural…as in coming from God. Such occurrences were first reported by mountain climbers before the era when airplane travel was common. I’m sure they still see them today too. Climbers would reach a mountain’s summit and suddenly see what seemed to be a figure standing in the distance. I must admit that such a sight would be a little disconcerting, but I wouldn’t mind seeing one. In the mid-1700s, members of a French scientific expedition ascended Pambamarca, a mountain in Ecuador. It seemed like a normal ascent, but when they reached its peak, they witnessed the sun breaking through the clouds, casting their shadows and encircling their heads with halo-like rings. Maybe that is how it happens, but I would say that the conditions would have to be exactly right for this to happen, and I think that is God. I can only imagine their thoughts at that moment…probably fear mixed with curiosity.

The mountain tops are not the only place this has been seen. Now that we are in the era of travel by planes, passengers gazing out of airplane windows have observed not just the aircraft’s shadow but also a rainbow ring encircling it, resembling a halo. Again, scientists have a tendency to explain this away, but I believe rainbows come from God. The phenomenon is known as a glory, pilot’s glory, or pilot’s halo. This phenomenon is not caused by the plane’s shadow itself but often appears alongside it, hence the name. That is part of the reason I don’t think it is an optical illusion. If it is, why don’t more people see it, more often?

A German physicist in the early 1900s, named Gustav Mie, went so far as to develop a mathematical formula to describe the scattering of light by water droplets in the air. I can’t imagine what mathematics would have to do with it, but the thought captivated him anyway. According to an article in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, “glories are produced by the backscattering, or angular deflection, of sunlight by minuscule water droplets in the atmosphere—droplets so small they measure just tens of wavelengths in diameter.” Scientists believe that the size of the rings varies with different wavelengths of light, depending on the average diameter of the droplets and their distribution. To observe a glory, one must be positioned directly between the light source and the water droplets, which explains why glories often appear alongside shadows. That’s where I start to think things would have to be a “little bit too perfect” for this to be coincidence.

Mie’s mathematics did not fully account for the workings of glories…little wonder there. In the 1980s, Nussenzveig and NASA scientist Warren Wiscombe discovered that the light contributing to a glory often does

not pass through the droplets. A 2014 article in Nature magazine believes that wave tunneling is primarily responsible for glories. This process supposedly occurs when sunlight comes close enough to a droplet to induce electromagnetic waves inside it. These waves circulate within the droplet before escaping, emitting the light rays that form the bulk of the glory observed. Believe what you want, but I think that these are little gifts from God.

not pass through the droplets. A 2014 article in Nature magazine believes that wave tunneling is primarily responsible for glories. This process supposedly occurs when sunlight comes close enough to a droplet to induce electromagnetic waves inside it. These waves circulate within the droplet before escaping, emitting the light rays that form the bulk of the glory observed. Believe what you want, but I think that these are little gifts from God.

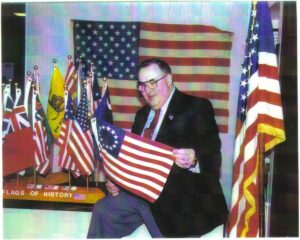

We have all heard about the importance of thinking ahead. It’s important in many situations, but unfortunately, it isn’t always appreciated. One case of forward thinking that rather backfired is the case of Robert G Heft. Heft, who went by Bob, was in high school in 1958, when his history teacher, Stanley Pratt, asked his class to make anything they wanted and bring it in for a show-and-tell. Heft took a little bit different approach than his classmates, and it rather backfired. While most of his classmates designed a conventional approach for their class project, Heft decided to do something a little more ambitious.

We have all heard about the importance of thinking ahead. It’s important in many situations, but unfortunately, it isn’t always appreciated. One case of forward thinking that rather backfired is the case of Robert G Heft. Heft, who went by Bob, was in high school in 1958, when his history teacher, Stanley Pratt, asked his class to make anything they wanted and bring it in for a show-and-tell. Heft took a little bit different approach than his classmates, and it rather backfired. While most of his classmates designed a conventional approach for their class project, Heft decided to do something a little more ambitious.

It was a noble effort, and definitely forward thinking, but when Heft brought his flag to school, his teacher was not impressed. Years later, Heft recalled, “He told me, ‘Why you got too many stars? You don’t even know how  many states we have.'” Heft received a B- for his project. Nevertheless, he was offered an opportunity to enhance his grade by persuading the US government to adopt his flag design. Despite the slim chances, Heft was determined. He initiated a campaign, writing letters and placing calls to the White House, urging the president to consider his flag.

many states we have.'” Heft received a B- for his project. Nevertheless, he was offered an opportunity to enhance his grade by persuading the US government to adopt his flag design. Despite the slim chances, Heft was determined. He initiated a campaign, writing letters and placing calls to the White House, urging the president to consider his flag.

Two years after Alaska and Hawaii were admitted as states, Heft was surprised with a call from President Dwight D Eisenhower, informing him that his design had been selected for the new 50-star flag. On July 4, 1960, Heft was honored with an invitation from President Eisenhower to attend a flag-raising ceremony at the US Capitol in Washington DC. Even Heft’s history teacher was impressed, saying, “I guess if it’s good enough for Washington, it’s good enough for me. I hereby change the grade to an A.” Well, that took a fair amount of decency on the part of the teacher. He could have let it go, but he didn’t.

Since that time, Heft’s banner has established a new record as the longest-serving U.S. flag. Heft pursued a career as a professor at Northwest State Community College in Archbold, Ohio, and held the position of mayor in Napoleon, Ohio. He gained recognition as a motivational speaker and made 14 visits to the White House. Anticipating future changes, Heft also crafted a 51-star American flag in the event that Washington DC, or Puerto Rico achieves statehood. His 51-star flag design features six alternating rows of stars with nine and

eight stars each.

eight stars each.

Heft, born in Saginaw, Michigan on January 19, 1942. He left Michigan following his parents’ separation when he was around a year old. He returned upon retiring from his professorship at Northwest State Community College in Archbold, Ohio. Robert G Heft, who passed away on December 12, 2009, at a hospital in Saginaw, Michigan, at the age of 67, will always be remembered as the student who created the 50-star American flag design.

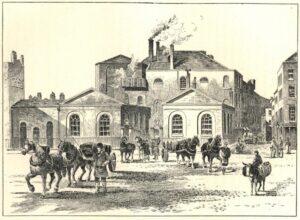

The London Beer Flood occurred as a result of an accident at Meux and Company’s Horse Shoe Brewery in London on October 17, 1814. The disaster unfolded when a 22-foot-tall wooden vat containing fermenting porter ruptured. The force of the escaping beer dislodged the valve of another vat and caused the destruction of several large barrels, releasing a total of between 128,000 and 323,000 imperial gallons (approximately 154,000 to 388,000 US gallons) of beer.

The London Beer Flood occurred as a result of an accident at Meux and Company’s Horse Shoe Brewery in London on October 17, 1814. The disaster unfolded when a 22-foot-tall wooden vat containing fermenting porter ruptured. The force of the escaping beer dislodged the valve of another vat and caused the destruction of several large barrels, releasing a total of between 128,000 and 323,000 imperial gallons (approximately 154,000 to 388,000 US gallons) of beer.

The wave of porter demolished the brewery’s rear wall and flooded the Saint Giles rookery, a slum area. Eight individuals died, including five mourners attending a wake for a two-year-old boy being held by an Irish family. The coroner’s inquest concluded that the eight died “casually, accidentally and by misfortune.” The brewery nearly faced bankruptcy due to the incident but was saved by a tax rebate from HM Excise on the beer lost. Following the disaster, the brewing industry moved away from using large wooden vats. In 1921, the brewery relocated, and the Dominion Theatre now stands in its place. Meux and Company was liquidated in 1961.

In the early 19th century, Meux Brewery was one of London’s two largest breweries, alongside Whitbread. Sir Henry Meux acquired the Horse Shoe Brewery in 1809, located at the intersection of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street. His father, Sir Richard Meux, had earlier been a co-owner of the Griffin Brewery on Liquor-Pond Street, now known as Clerkenwell Road, where he built London’s largest vat, with a capacity of 20,000 imperial barrels. Henry Meux followed in his father’s footsteps by constructing a large vat, a wooden vessel standing 22 feet high and capable of holding 18,000 imperial barrels. To reinforce the vat, eighty long tons of iron hoops were utilized. Meux exclusively brewed porter, a dark beer originating from London and highly favored as the capital’s most popular alcoholic beverage. In the year leading up to July 1812, Meux and Company produced 102,493 imperial barrels. The porter was aged in these large vessels for several months, and up to a year for the highest quality brews.

Behind the brewery lay New Street, a small dead-end road connecting to Dyott Street, situated within the Saint Giles rookery. Spanning eight acres, the rookery was a constantly deteriorating slum teetering on the brink of social and economic collapse, as noted by Richard Kirkland, a professor of Irish literature. Thomas Beames, a preacher at Westminster St James and the author of “The Rookeries of London: Past, Present and Prospective” (1852), referred to the Saint Giles rookery as a gathering place for society’s outcasts. This area also served as the muse for William Hogarth’s 1751 artwork, “Gin Lane.”

Around 4:30pm on October 17, 1814, George Crick, the storehouse clerk at Meux’s Brewery, noticed that one of the iron bands weighing 700 pounds had slipped off a vat. The vessel, standing 22 feet tall, was nearly full, containing 3,555 imperial barrels of ten-month-old porter, filled to within four inches from the top. Since such slippages occurred two or three times annually, Crick was not alarmed. He reported the issue to his supervisor, who assured him it would cause no harm. Crick was instructed to write a note to Mr Young, a brewery partner, to address the repair later.

An hour after a hoop detached, Crick stood thirty feet from the vat, note in hand for Mr Young, when suddenly, the vat burst without warning. The released liquid’s force dislodged a stopcock from an adjacent vat, causing it to release its contents; several hogsheads of porter were lost, contributing to the deluge. An estimated 128,000 to 323,000 imperial gallons were spilled. The brewery’s rear wall, 25 feet high and two and a half bricks thick, was demolished by the force. Bricks from the wall were propelled upwards, landing on the roofs of houses along Great Russell Street.

A 15-foot-high wave of porter crashed into New Street, demolishing two houses and severely damaging two others. In one of the destroyed homes, four-year-old Hannah Bamfield was having tea with her mother and another child when the beer wave swept the mother and the other child into the street, resulting in Hannah’s death. At the second house, a wake for a two-year-old boy was in progress; the boy’s mother, Anne Saville, and four mourners perished. Eleanor Cooper, a 14-year-old servant at the Tavistock Arms on Great Russell Street, was killed by a collapsing brewery wall while she was washing pots. Another victim, Sarah Bates, was found deceased in a different house on New Street. The surrounding land, being flat and poorly drained, allowed the beer to flood into cellars, forcing inhabitants to climb onto furniture to escape drowning. Everyone at the brewery survived, though three workers were rescued from the debris; the superintendent and one worker were taken to Middlesex Hospital with three others.

Rumors began to emerge of hundreds gathering to collect the beer, followed by widespread drunkenness, and a fatality due to alcohol poisoning days later. However, brewing historian Martyn Cornell insists that contemporary newspapers did not mention such chaos or the subsequent death; rather, they depicted the crowds as orderly. Cornell notes that the prevalent press at the time harbored an aversion to the immigrant Irish community in Saint Giles, suggesting that any misconduct would have been reported.

The vicinity behind the brewery revealed a “scene of desolation [that] presents a most awful and terrific appearance, akin to what one might expect from fire or earthquake.” Brewery watchmen charged onlookers to see the remnants of the shattered beer vats, attracting several hundred viewers. Those mourners who perished in the cellar received their own vigil at The Ship public house on Bainbridge Street. Meanwhile, the other victims were displayed by their families in a nearby yard, drawing public attention and financial contributions for their burials. Broader fundraising efforts were also initiated for the affected families.

The coroner’s inquest was held at the Workhouse of the Saint Giles parish on October 19, 1814; George Hodgson, the coroner for Middlesex, oversaw proceedings. The details of the victims were read out as: Eleanor Cooper, age 14; Mary Mulvey, age 30; Thomas Murry, age 3 (Mary Mulvey’s son); Hannah Bamfield, age 4 years 4 months; Sarah Bates, age 3 years 5 months; Ann Saville, age 60; Elizabeth Smith, age 27; and Catherine Butler, age 65.

Hodgson led the jurors to the event’s location, where they observed the brewery and the deceased prior to gathering witness testimony. The initial testimony came from George Crick, who witnessed the entire incident; his brother was among the injured at the brewery. Crick noted that the vat hoops would fail a few times annually, yet this had not previously led to any incidents. Testimonies were also presented by Richard Hawse, the proprietor of the Tavistock Arms, who lost a barmaid in the tragedy, among others. The jury concluded that the eight victims died “casually, accidentally, and by misfortune”. When the coroner’s inquest concluded with a verdict of an act of God, Meux and Company were not required to pay compensation. However, the disaster, including the lost porter, the damaged buildings, and the vat replacement, cost the company £23,000. Following a private petition to Parliament, they received approximately £7,250 from HM Excise, which prevented their bankruptcy. The Horse Shoe Brewery resumed operations shortly thereafter but ceased in 1921 when Meux

transferred their production to the Nine Elms brewery in Wandsworth, acquired in 1914. At closure, the brewery spanned 103,000 square feet. It was demolished the subsequent year, and the Dominion Theatre was constructed on its location. Meux and Company was liquidated in 1961. Following the accident, the brewing industry gradually replaced large wooden tanks with lined concrete vessels.

transferred their production to the Nine Elms brewery in Wandsworth, acquired in 1914. At closure, the brewery spanned 103,000 square feet. It was demolished the subsequent year, and the Dominion Theatre was constructed on its location. Meux and Company was liquidated in 1961. Following the accident, the brewing industry gradually replaced large wooden tanks with lined concrete vessels.

The 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron, part of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAF), is stationed in Edinburgh, Scotland. Established on October 14, 1925, at RAF Turnhouse, it served as a day bomber unit within the Auxiliary Air Force. Initially, the squadron operated DH.9As (a British single engine biplane) and utilized Avro 504Ks (a biplane bomber) for training purposes. In March 1930, it transitioned to Wapitis (a two-seater general purpose military biplane), which were subsequently replaced by Harts (a British two-seater biplane light bomber) in February 1934. On October 24, 1938, the squadron was reclassified as a fighter unit, operating Hinds (a British light bomber) until the introduction of Gladiators (a British biplane fighter) in late March 1939. Over those years the men of 603 Squadron made many equipment transitions.

The 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron, part of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAF), is stationed in Edinburgh, Scotland. Established on October 14, 1925, at RAF Turnhouse, it served as a day bomber unit within the Auxiliary Air Force. Initially, the squadron operated DH.9As (a British single engine biplane) and utilized Avro 504Ks (a biplane bomber) for training purposes. In March 1930, it transitioned to Wapitis (a two-seater general purpose military biplane), which were subsequently replaced by Harts (a British two-seater biplane light bomber) in February 1934. On October 24, 1938, the squadron was reclassified as a fighter unit, operating Hinds (a British light bomber) until the introduction of Gladiators (a British biplane fighter) in late March 1939. Over those years the men of 603 Squadron made many equipment transitions.

In August 1939, the squadron commenced yet another transition, this time to Spitfires (a British single-seat fighter aircraft). As the war loomed closer, the squadron shifted to full-time operations. Within two weeks of the outbreak of World War II, Brian Carbury was permanently assigned, and the squadron started receiving Spitfires, transferring its Gladiators to other squadrons throughout October.

Scotland was within the range of Nazi Germany’s long-range bombers and reconnaissance planes. The Luftwaffe primarily targeted the Royal Naval Home Fleet at Scapa Flow. The 603 Squadron, now equipped with Spitfires, was ready in time to intercept the first German air raid on the British Isles on October 16th. It succeeded in shooting down a Junkers Ju 88 bomber over the Firth of Forth, north of Port Seton…marking the first enemy aircraft downed over Great Britain since 1918 and the RAF’s initial victory in World War II. The squadron continued its defensive role in Scotland until August 27, 1940, after which it rotated to Southern England, joining Number 11 Group at RAF Hornchurch. There, it participated in the remaining months of the Battle of Britain, starting from August 27, 1940.

Two days after becoming operational in southern England, Carbury secured his first of 15½ victories (not sure how one has a half victory), ranking as the fifth highest scoring fighter ace of the battle. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar with 603 Squadron during the conflict. Air Commodore Ronald ‘Ras’ Berry achieved approximately 9 (of a final total of 14) victories at this time, while RAF Officer ‘Sheep’ Gilroy claimed more than 6 victories. Flight Lieutenant Richard Hillary, with 5 victories, was shot down on September 3rd during a skirmish with BF 109s of Jagdgeschwader 26 off Margate at 10:04am. Rescued by the Margate lifeboat, he suffered severe burns and subsequently spent three years in hospital, where he authored the book, The Last Enemy. Recent academic research, including an examination of German records, has identified 603 Squadron as the highest-scoring squadron in the Battle of Britain by its conclusion.

Upon returning to Scotland in late December, Carbury inflicted damage on a Ju 88 over Saint Abb’s Head on Christmas Day. He then departed from the squadron in January 1941 to serve as an instructor at the Central

Flying School. By May 1941, the squadron had relocated southward to participate in sweeps over France, known as “rhubarbs,” which continued until the year’s end.

Flying School. By May 1941, the squadron had relocated southward to participate in sweeps over France, known as “rhubarbs,” which continued until the year’s end.

Following a period in Scotland, 603 Squadron departed in April 1942 for the Middle East, with its ground echelon arriving in early June. Simultaneously, Flight Sergeant Joe Dalley transitioned from the squadron to Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) duties, piloting a Spitfire PR from RAF Benson directly to Malta. There, he joined 69 Squadron RAF, becoming one of the four pilots dubbed the “Eyes and Ears” of the Island. The squadron’s aircraft were loaded onto the US aircraft carrier Wasp and launched towards Malta on April 20th to bolster the island’s hard-pressed defenders. After almost four months of defending Malta, the surviving pilots and planes were integrated into 229 Squadron on August 3, 1942.

By the end of June 1942, the ground echelon of 603 Squadron had relocated to Cyprus, where it operated as a servicing unit for six months before its return to Egypt. In February 1943, the arrival of Bristol Beaufighters and their crews marked the commencement of convoy patrols and escort missions along the North African coastline. August saw the initiation of sweeps over the Aegean’s German-occupied islands and areas off Greece. The squadron continued its assaults on enemy shipping until a scarcity of targets facilitated its return to the UK in December 1944.

On January 10, 1945, 603 Squadron reformed at RAF Coltishall and, in a curious twist of fate, inherited the Spitfires and some personnel of 229 Squadron RAF…the very squadron that had previously absorbed 603 Squadron at Ta’ Qali in 1942. Fighter-bomber operations commenced in February over the Netherlands and persisted until April. Subsequently, the squadron returned to its home base at Turnhouse for the concluding days of the war. The squadron was officially disbanded on August 15, 1945.

603 Squadron was reestablished as part of the Auxiliary Air Force on May 10, 1946, and started recruiting for a Spitfire squadron in June at RAF Turnhouse. The squadron received its first Spitfire in October and operated this aircraft until it transitioned to the De Havilland Vampire FB.5s in May 1951. By July, the squadron was fully equipped with the new aircraft, which it flew until the unit was disbanded on March 10, 1957.

The new 603 Squadron originated from Number 2 (City of Edinburgh) Maritime Headquarters Unit in October 1999, providing the foundation for the new 602 (City of Glasgow) Squadron RAuxAF in 2006. 603 Squadron continued to be based in Edinburgh. In 2007, to mark the 50th Anniversary of the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight, the Flight’s Supermarine Spitfire IIa, P7350, which served in 603 Squadron during the Battle of Britain, bore the squadron’s code XT-L, the same as Gerald ‘Stapme’ Stapleton’s personal aircraft, for two years.

For several years leading up to 2013, the main trade at 603 Squadron was the RAF Regiment, although the Squadron also provided support in Mission Support and Flight Operations trades. In late 2012, it was announced that the Squadron would start recruiting for the RAF Police in 2013. Consequently, the Squadron has transitioned to primarily being an RAF Police unit, while still retaining a Flight of the RAF Regiment.

For several years leading up to 2013, the main trade at 603 Squadron was the RAF Regiment, although the Squadron also provided support in Mission Support and Flight Operations trades. In late 2012, it was announced that the Squadron would start recruiting for the RAF Police in 2013. Consequently, the Squadron has transitioned to primarily being an RAF Police unit, while still retaining a Flight of the RAF Regiment.

At the onset of the Civil War, combat involved bayonets, horses, wooden ships, and inaccurate artillery. As the war progressed, the armaments evolved to include mines, precise firearms, more lethal bullets, torpedoes, and ironclad ships as the new norm. Although the majority of battles were fought on land, the struggle for naval supremacy was a pivotal aspect of the war. Control over the coastline meant control over vital imports from Europe and Coastal America, including essential supplies like clothing, food, artillery, medicine, and occasionally, reinforcements.

At the onset of the Civil War, combat involved bayonets, horses, wooden ships, and inaccurate artillery. As the war progressed, the armaments evolved to include mines, precise firearms, more lethal bullets, torpedoes, and ironclad ships as the new norm. Although the majority of battles were fought on land, the struggle for naval supremacy was a pivotal aspect of the war. Control over the coastline meant control over vital imports from Europe and Coastal America, including essential supplies like clothing, food, artillery, medicine, and occasionally, reinforcements.

As the United States Navy was constructing its first submarine, the USS Alligator, in late 1861, the Confederacy was also developing their own. Driven by a deep loyalty to the Confederate states and recognizing the potential financial benefits of sinking enemy ships, Horace Hunley, James McClintock (the designer), and Baxter Watson constructed the Pioneer. It underwent testing in the Mississippi River in February 1862 and was later moved to Lake Pontchartrain for further trials. The Union’s approach towards New Orleans led the team to halt development, and the Pioneer was scuttled in the following month. McClintock acknowledged the potential of a boat that could navigate freely at any depth, yet he believed improvements were necessary. The team, including Hunley, Watson, and McClintock, relocated to Mobile to work on a second submarine, the American Diver, in collaboration with Thomas Park and Thomas Lyons of Park and Lyons machine shops. The Confederate States Army supported their efforts, with Lieutenant William Alexander of the 21st Alabama Infantry Regiment overseeing the project. The builders tried various propulsion methods, including McClintock’s electromagnetic drive and a custom steam engine, but ultimately chose a hand-cranked system to avoid the excessive time and cost of more complex engines. By January 1863, the American Diver was ready for harbor trials, but its slow speed rendered it impractical. Despite this, an attack on the Union blockade was attempted by towing the submarine to Fort Morgan. Unfortunately, the submarine was lost to the turbulent waters and strong currents at the entrance of Mobile Bay during bad weather. The crew managed to escape, but the vessel was not retrieved.

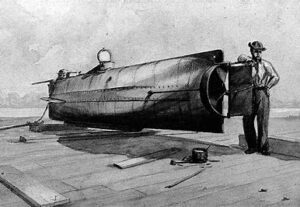

The third submarine was the one that was eventually launched. The H.L. Hunley, also known as the CSS H.L. Hunley, played a minor role in the American Civil War. The Hunley demonstrated both the potential and perils of underwater combat. It became the first combat submarine to sink an enemy warship when it sunk the USS Housatonic. However, the Hunley was not fully submerged during the attack and was lost with all hands before it could return to base. Throughout its brief service, the Hunley sank three times, resulting in the deaths of twenty-one crewmen. The submarine was named after its inventor, Horace Lawson Hunley, and was commandeered by the Confederate States Army in Charleston, South Carolina.

The Hunley, measuring nearly 40 feet in length, was constructed in Mobile, Alabama, and set afloat in July 1863. Subsequently, it was transported via rail to Charleston on August 12, 1863. Initially known as the “fish boat,” “fish torpedo boat,” or “porpoise,” the Hunley first sank during a trial run on August 29, 1863, resulting in the death of five crew members. Tragically, it sank once more on October 15, 1863, claiming the lives of all eight crew members, including Horace Lawson Hunley, who was on board despite not being part of the Confederate military. After each incident, the Hunley was recovered and restored to service…until February 17, 1864, that is. That day, the Hunley attacked and sank the 1,240-ton United States Navy screw sloop-of-war Housatonic, which had been on Union blockade-duty in Charleston’s outer harbor. Again, the Hunley didn’t survive the attack, taking all eight members of the third crew with it. This time, the Hunley was also lost.

For years, the Hunley lay at the bottom of the harbor, but she was finally located in 1995. The Hunley was

recovered in 2000 and is exhibited at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, located on the Cooper River in North Charleston, South Carolina. A 2012 examination of the artifacts retrieved from the Hunley indicated that the submarine was approximately 20 feet from its target, the Housatonic, when the torpedo it had deployed detonated, leading also to the submarine’s demise.

recovered in 2000 and is exhibited at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, located on the Cooper River in North Charleston, South Carolina. A 2012 examination of the artifacts retrieved from the Hunley indicated that the submarine was approximately 20 feet from its target, the Housatonic, when the torpedo it had deployed detonated, leading also to the submarine’s demise.

The USS Cole, an American naval destroyer, captained by Commander Kirk Lippold, arrived in Aden, Yemen at the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula for refueling, en route to join US warships enforcing trade sanctions against Iraq. At 12:15pm local time, a motorized rubber dinghy filled with explosives created a 40-by-40-foot hole in the port side of the ship, while it was docked for refueling in Aden. How could it have been that easy? The attack, which resulted in the death of seventeen sailors and wounded thirty-eight, was perpetrated by two suicide terrorists believed to be affiliated with Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda network.

The USS Cole, an American naval destroyer, captained by Commander Kirk Lippold, arrived in Aden, Yemen at the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula for refueling, en route to join US warships enforcing trade sanctions against Iraq. At 12:15pm local time, a motorized rubber dinghy filled with explosives created a 40-by-40-foot hole in the port side of the ship, while it was docked for refueling in Aden. How could it have been that easy? The attack, which resulted in the death of seventeen sailors and wounded thirty-eight, was perpetrated by two suicide terrorists believed to be affiliated with Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda network.

The blast resulted in significant flooding aboard the warship, causing it to list slightly. Nevertheless, by nightfall, the crew had successfully halted the water flooding in, thereby keeping the Cole afloat. Following the assault, President Bill Clinton directed US vessels in the Persian Gulf to evacuate the area and proceed to the open sea. He then dispatched large contingent of American investigators to Aden for a thorough inquiry. The group included FBI agents dedicated to probing potential connections to Osama bin Laden. Bin Laden had already been indicted in the United States for orchestrating the 1998 embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, which claimed the lives of 224 individuals, among them 12 Americans, so it was not a far stretch to think he would have a hand in this attack too.

The USS Cole’s brief four-hour stopover indicates that the terrorists had inside information about its unscheduled visit to the Aden fueling station. The small boat used by the terrorists merged seamlessly with other harbor vessels aiding the Cole’s mooring process and managed to get close to the US warship undetected. Upon detonation of their dinghy, a substantial explosion ripped through the Cole’s port side, causing extensive damage to the engine room, mess hall, and living quarters. Witnesses aboard the Cole reported seeing both terrorists stand up moments before the blast, typical of suicide bombers.

In all, six individuals were suspected of involvement in the Cole attack. They were quickly detained in Yemen, but due to the lack of cooperation from Yemeni officials, the FBI has been unable to definitively connect the

attack to bin Laden, even though we all know that he masterminded it. This kind of attack was so typical of the type of attack that would later make bin Laden well known as a major player in attacks against American targets. As for Americans, these leaks and the inability of the FBI to resolve the issue are some of the biggest reasons that many Americans don’t trust the FBI today.

attack to bin Laden, even though we all know that he masterminded it. This kind of attack was so typical of the type of attack that would later make bin Laden well known as a major player in attacks against American targets. As for Americans, these leaks and the inability of the FBI to resolve the issue are some of the biggest reasons that many Americans don’t trust the FBI today.

Sellafield, which was formerly known as Windscale Works, was an important multi-functional nuclear site located near Seascale on the coast of Cumbria, England. As of August 2022, its primary activities are the processing and storage of nuclear waste, along with decommissioning. Historically, the facility produced nuclear power from 1956 to 2003 and reprocessed nuclear fuel from 1952 to 2022. Originally built as a Royal Ordnance Factory in 1942, the site was briefly owned by Courtaulds for rayon production in the post-World War II years. Then in 1947, the Ministry of Supply reacquired it for plutonium production, leading to the construction of the Windscale Piles and the First-Generation Reprocessing Plant, and its renaming to “Windscale Works.” Significant developments followed, including the construction of Calder Hall, the world’s first commercial nuclear power station to supply electricity to a public grid, the Magnox fuel reprocessing plant, the prototype Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor (AGR), and the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (THORP). Decommissioning has been concentrated on the Windscale Piles, Calder Hall, and various historic reprocessing and waste storage facilities.

Sellafield, which was formerly known as Windscale Works, was an important multi-functional nuclear site located near Seascale on the coast of Cumbria, England. As of August 2022, its primary activities are the processing and storage of nuclear waste, along with decommissioning. Historically, the facility produced nuclear power from 1956 to 2003 and reprocessed nuclear fuel from 1952 to 2022. Originally built as a Royal Ordnance Factory in 1942, the site was briefly owned by Courtaulds for rayon production in the post-World War II years. Then in 1947, the Ministry of Supply reacquired it for plutonium production, leading to the construction of the Windscale Piles and the First-Generation Reprocessing Plant, and its renaming to “Windscale Works.” Significant developments followed, including the construction of Calder Hall, the world’s first commercial nuclear power station to supply electricity to a public grid, the Magnox fuel reprocessing plant, the prototype Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor (AGR), and the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (THORP). Decommissioning has been concentrated on the Windscale Piles, Calder Hall, and various historic reprocessing and waste storage facilities.

During its “Windscale Works” years, a severe fire broke out in the core of a nuclear reactor on October 10, 1957. As a result, significant radioactive material was released into the environment on October 10-11, 1957. Windscale Works was under the operation of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) at the time. On the 15th of October, the UKAEA Chairman announced the formation of an Inquiry Committee, chaired by Sir William Penney, to investigate the incident. The Committee convened at  Windscale Works from October 17–25th. They interviewed 37 individuals and reviewed 73 technical exhibits. They submitted their findings to the UKAEA Chairman on 26th October. These findings underpinned a UK Government White Paper (Command Paper 302), published on November 8, 1957. Oddly or perhaps criminally, the Penney Report itself remained unpublished until it was made available at The National Archives, Kew, in January 1988, basically covering up the event for decades. This event transpired when uranium metal fuel caught fire within Windscale Pile No. 1. The fire led to the release of radioactive contamination into the environment, which is estimated to have eventually caused approximately 240 cancer cases, with fatalities between 100 to 240. The incident received a level 5, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The maximum rating is 7.

Windscale Works from October 17–25th. They interviewed 37 individuals and reviewed 73 technical exhibits. They submitted their findings to the UKAEA Chairman on 26th October. These findings underpinned a UK Government White Paper (Command Paper 302), published on November 8, 1957. Oddly or perhaps criminally, the Penney Report itself remained unpublished until it was made available at The National Archives, Kew, in January 1988, basically covering up the event for decades. This event transpired when uranium metal fuel caught fire within Windscale Pile No. 1. The fire led to the release of radioactive contamination into the environment, which is estimated to have eventually caused approximately 240 cancer cases, with fatalities between 100 to 240. The incident received a level 5, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The maximum rating is 7.

Now called Sellafield, the licensed premises span 650 acres, housing over 200 nuclear facilities and more than 1,000 buildings. It stands as the largest nuclear site in Europe, boasting the world’s most varied array of nuclear facilities on a single site. Workforce numbers fluctuate, but prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the site  employed around 10,000 individuals. The Central Laboratory and headquarters of the UK’s National Nuclear Laboratory are located on the premises. The site is owned by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA), a non-departmental public body of the UK government. From 2008 to 2016, it was managed by a private consortium before control reverted to the government. Consequently, the Site Management Company, Sellafield Ltd, became a subsidiary of the NDA. The decommissioning process of the legacy facilities, which includes structures from the UK’s early efforts to develop an atomic bomb, is expected to be completed by 2120 at an estimated cost of £121 billion.

employed around 10,000 individuals. The Central Laboratory and headquarters of the UK’s National Nuclear Laboratory are located on the premises. The site is owned by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA), a non-departmental public body of the UK government. From 2008 to 2016, it was managed by a private consortium before control reverted to the government. Consequently, the Site Management Company, Sellafield Ltd, became a subsidiary of the NDA. The decommissioning process of the legacy facilities, which includes structures from the UK’s early efforts to develop an atomic bomb, is expected to be completed by 2120 at an estimated cost of £121 billion.

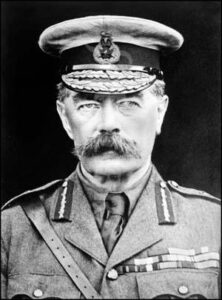

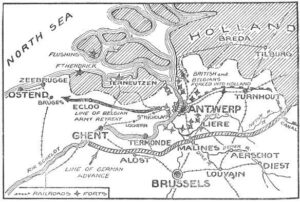

The initiative to send a relief army to support Antwerp did not begin with Winston Churchill, but with Lord Kitchener and the French Government. Churchill was not involved or consulted about the plans until they were well underway, with significant troop movements already in progress or planned. Deciding that he should be brought into the loop, Churchill was summoned to a midnight meeting at Lord Kitchener’s residence on October 2, 1914. It was during this meeting that he fully grasped the progress of the plans to send a relief army to Antwerp, a coordination between Lord Kitchener and the French Government. He learned as well that no definitive commitments had been made to the Belgian Government. On that same afternoon, the Belgian Government had resolved to evacuate Antwerp, pull back the field army from the fort, and effectively abandon the city’s defense.

The initiative to send a relief army to support Antwerp did not begin with Winston Churchill, but with Lord Kitchener and the French Government. Churchill was not involved or consulted about the plans until they were well underway, with significant troop movements already in progress or planned. Deciding that he should be brought into the loop, Churchill was summoned to a midnight meeting at Lord Kitchener’s residence on October 2, 1914. It was during this meeting that he fully grasped the progress of the plans to send a relief army to Antwerp, a coordination between Lord Kitchener and the French Government. He learned as well that no definitive commitments had been made to the Belgian Government. On that same afternoon, the Belgian Government had resolved to evacuate Antwerp, pull back the field army from the fort, and effectively abandon the city’s defense.

The men were deeply troubled by the Belgian Government’s plan. It appeared that just as help was within reach, everything might be sacrificed for a mere three or four days of further resistance. Under these conditions, Churchill proposed to immediately travel to Antwerp to inform the Belgian Government of the ongoing efforts, assess the situation firsthand, and explore how the defense could be extended until a relief force was ready. The others agreed to Churchill’s proposal, and he promptly made his way across the Channel.

The next day, after discussions with the Belgian Government and British Staff officers in Antwerp overseeing the operations, Churchill presented a cautious telegraphic proposal. He avoided any declarations on behalf of the British Government that might encourage the Belgians to hold out for support he couldn’t guaranteed.

Churchill’s proposal was concise and transmitted via telegram. It stated: “The Belgians were to continue the resistance to the utmost limit of their power. The British and French Governments were to say within three days definitely whether they could send a relieving force or not, and what the dimensions of that force would be.

In the event of their not being able to send a relieving force the British Government were to send in any case to Ghent and other points on the line of retreat British troops sufficient to insure the safe retirement of the Belgian field army, so that the Belgian  field army would not be compromised through continuing the resistance on the Antwerp fortress line.

field army would not be compromised through continuing the resistance on the Antwerp fortress line.

Incidentally, we were to aid and encourage the defense of Antwerp by the sending of naval guns, naval brigades, and any other minor measures likely to enable the defenders to hold out the necessary number of days.”

The proposal was contingent upon approval from both parties. It remained unsettled until it received the acceptance of both governments. Upon agreement, Churchill received a telegraph announcing the dispatch of a relief army, including its size and structure, which I was to communicate to the Belgians. Churchill was instructed to do all in his power to sustain the defense in the interim, which he did, disregarding any potential repercussions.

Churchill chose not to recount the well-known military events, but he believed it would be erroneous to view Lord Kitchener’s attempts to relieve Antwerp, in which Churchill had a significant but secondary role, as a venture that resulted solely in adversity.

Churchill believed that military history would deem the outcomes highly favorable to the Western Allies. The significant battle that began on the Aisne was extending daily towards the sea. Sir John French’s forces were assembling and commencing the Battle of Armentières, which led to the pivotal Battle of Ypres, amid an ever-changing situation.

The prolonged defense of Antwerp, even by just a few days, detained substantial German forces near the fortress. The sudden and audacious deployment of a new British division and a British cavalry division at Ghent, among other places, perplexed the cautious German command, causing them to anticipate the arrival of a large force from the sea.

Regardless, their advance was tentative, faced with only weak opposition, and Churchill was convinced that history would confirm, certainly in his view and that of many esteemed military officers of the time, that the

entirety of this operation…the movement of the British and associated French troops…though it failed to save Antwerp, resulted in the great battle being fought along the Yser, rather than twenty or thirty miles to the south, and if that was the case, then the losses sustained by the naval division, fortunately not severe in terms of lives, will undoubtedly have been justified for the greater good.

entirety of this operation…the movement of the British and associated French troops…though it failed to save Antwerp, resulted in the great battle being fought along the Yser, rather than twenty or thirty miles to the south, and if that was the case, then the losses sustained by the naval division, fortunately not severe in terms of lives, will undoubtedly have been justified for the greater good.